Towards Diagnosing and Mitigating Behavioral Cyber Risks

Abstract

1. Introduction

How can we accurately diagnose and mitigate cyber vulnerabilities linked to human behavior?

2. A Review of the Current Literature

2.1. Diagnosing Cyber Behavioral Vulnerability

2.2. Influencing Risk Behavior

3. Methodology and Preliminary Results

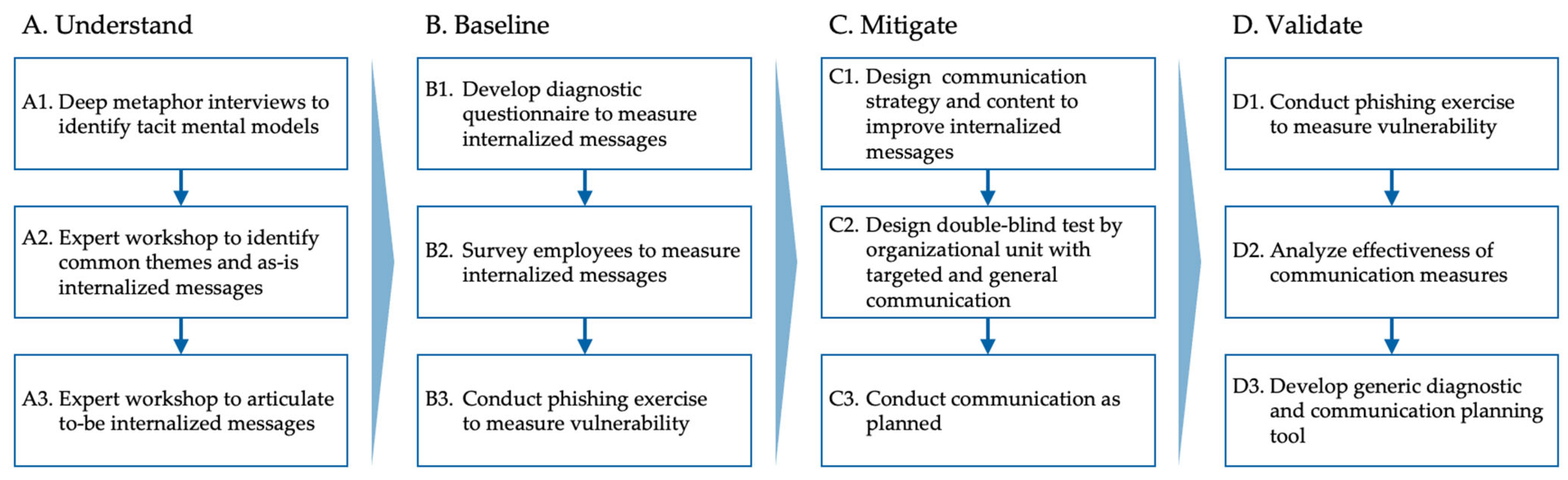

3.1. Understand

3.2. Baseline

3.3. Mitigate

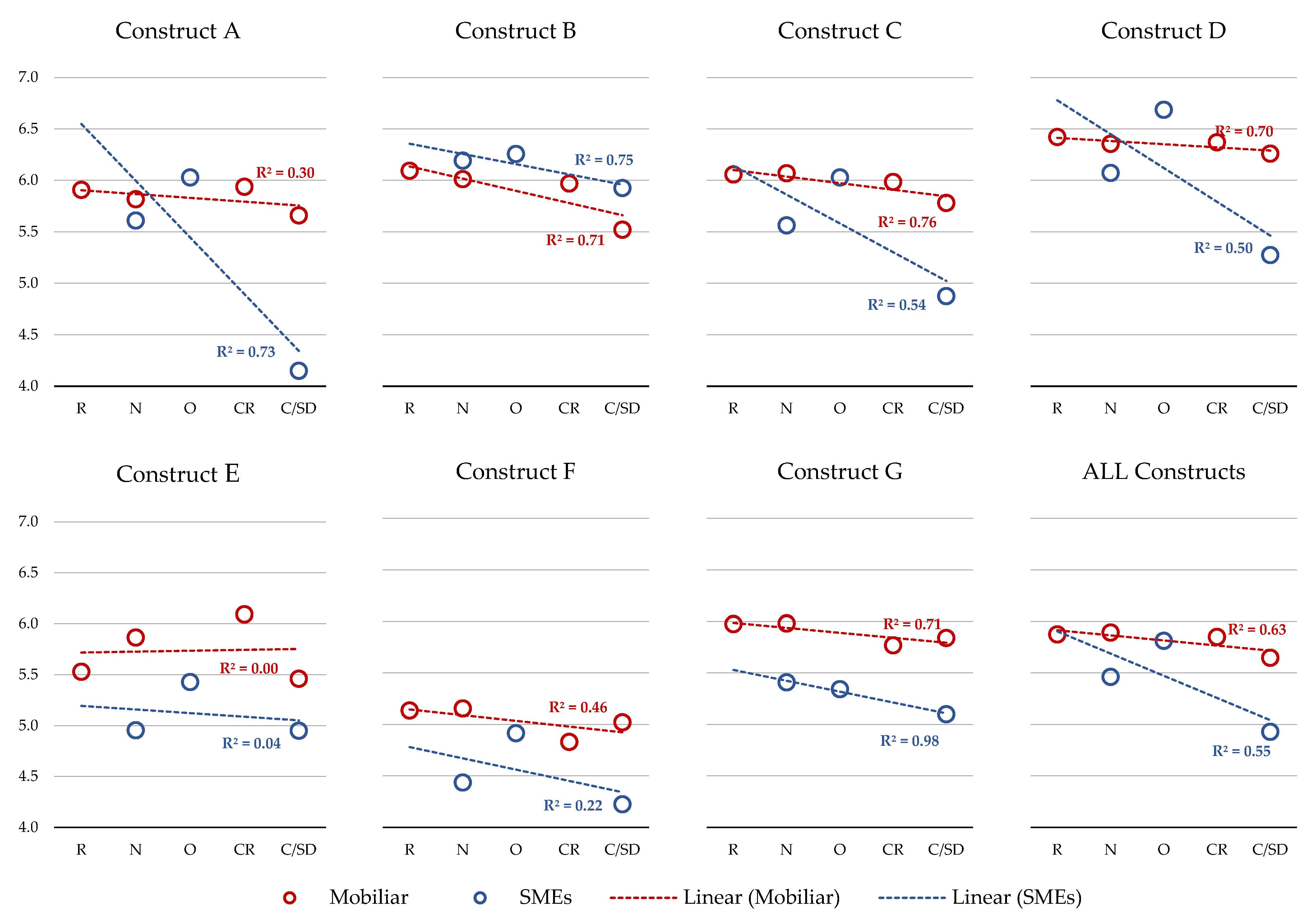

3.4. Validate

4. Discussion and Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Internalized to-Be Messages | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| A | My company and I have valuable information, we are targeted by hackers, and we need to protect ourselves. | Even though we think we may be small, our company has valuable information on customers, technology, markets, and bank accounts, and this information is valuable. I, as an employee, have access to this important information. Both I and the company can be targeted, and we need to be alert at all times and protect ourselves. |

| B | We can make mistakes, and we need to continue our business activities with better risk awareness. | My coworkers and I can make mistakes if/when we are not paying attention. We need to therefore pay attention. On the other hand, it is not possible to not make any mistakes at all while conducting business, so we need to learn to recognize them, communicate openly when they occur, develop ways to cope with them, and continue to try to minimize them. |

| C | I have a responsibility to do something. | Defending my company’s valuable information is not somebody else’s job. It is also my job. Other people also carry a responsibility (the CEO, management, the IT department, IT consultants, all employees), but I carry my fair share of this responsibility. I therefore have to pay attention, communicate openly, and take corrective action as needed. |

| D | I have to protect the company with my behavior during regular business activities. | My behavior while conducting normal business transactions (email with clients and partners, entering the facilities, etc.) can create vulnerabilities for hackers to exploit. I therefore have to remain vigilant not just at special times but throughout my activities. |

| E | I can and should do something in case of a cyber-attack. I am an important part of the response and can be creative to support our customers. | The response in case of a cyber-attack is the responsibility of all employees, not just of a few IT specialists and management. It is my responsibility to ensure the impact on our customers and partners is kept to a minimum. This can only be carried out by the people who have interacted with our external partners before and understand their needs. Sometimes it may require being creative and flexible regarding the best solution, rather than waiting for the situation to normalize or just following orders. |

| F | I know how to respond in case of a cyber-attack and have trained in alternative business processes. | Responding to an attack in progress can be somewhat chaotic and proper responses need to be prepared and trained prior to an event in order to be effective. In the case of cyber, they may involve alternative processes less reliant on company technology—for example personal mobile phones, pens, and paper. It is important to train these processes and understand how to carry them out under the proper conditions—much in the same way that a ship’s crew conducts firefighting drills. |

| G | We need to learn from cyber-attacks and continue to evolve our preparedness and response. | Each attack, both the successful and unsuccessful, provides important information about vulnerabilities and capabilities to respond. It is important to understand what these breaches or near misses signal and how to integrate this knowledge into our training and responses. This information needs to therefore be shared with and understood by employees. |

| ID | Internalized to-Be Messages | ID | Question | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | My company and I have valuable information, we are targeted by hackers, and we need to protect ourselves. | 911 | My company is not a target for hackers. | 0.98 |

| 914 | My company fits the target profile of hackers. | 0.92 | ||

| 891 | Our company data are only valuable to us | 0.70 | ||

| 916 | My company is not threatened by hackers. | 0.70 | ||

| 898 | I can be targeted by hackers because of my access. | 0.68 | ||

| 908 | I am a potential target for hackers. | 0.68 | ||

| 901 | Hackers are interested in our company. | 0.67 | ||

| 917 | My company’s data are worth being protected. | 0.60 | ||

| 906 | My company has been attacked by hackers. | 0.59 | ||

| 907 | We are targeted by hackers. | 0.55 | ||

| B | We can make mistakes, and we need to continue our business activities with better risk awareness. | 929 | I may make mistakes that expose the company to cyber-attacks. | 0.72 |

| 925 | Making mistakes regarding cybersecurity is nothing to be ashamed of. | 0.65 | ||

| 1035 | To defend the company against hackers means to communicate openly about mistakes. | 0.65 | ||

| 933 | We need to recognize cybersecurity mistakes fast. | 0.60 | ||

| 927 | We need to communicate openly when we notice mistakes regarding cybersecurity. | 0.58 | ||

| 934 | I have made mistakes regarding cybersecurity, but I have learned from them. | 0.53 | ||

| 936 | I have made cybersecurity mistakes in the past. | 0.49 | ||

| 1034 | I have to pay attention to my behavior and take corrective actions if needed to ensure the safety of the company’s data. | 0.48 | ||

| 935 | We should share our cybersecurity mistakes to learn and minimize future risks. | 0.47 | ||

| 930 | Mistakes at work can expose the company to cyber-attacks. | 0.45 | ||

| C | I have a responsibility to do something. | 942 | Our IT department alone is responsible for cybersecurity. | 0.75 |

| 939 | Defending the company’s valuable information is everyone’s job, independent of their position and function. | 0.55 | ||

| 937 | Paying attention to cybersecurity is not part of my job. | 0.54 | ||

| 944 | I can and should motivate my colleagues to help me defend company data. | 0.53 | ||

| 947 | I am an essential part of the defense against cyber-attacks. | 0.53 | ||

| 1038 | The company’s cybersecurity depends on my behavior. | 0.52 | ||

| 1036 | I have to be careful with our company data and information. | 0.51 | ||

| 1044 | I handle company data and information vigilantly. | 0.51 | ||

| 946 | I do not have any responsibility for the safeguarding of company data. | 0.50 | ||

| 1045 | I have to be careful with company data and information. | 0.48 | ||

| D | I have to protect the company with my behavior during regular business activities. | 966 | Only at special times do I need to be aware of cyber risks when conducting business activities. | 0.83 |

| 977 | My behavior during regular business activities influences the cybersecurity of the company. | 0.83 | ||

| 964 | I need to be cybersecurity-aware throughout the day, not only during extraordinary times. | 0.78 | ||

| 972 | My behavior while working can protect the company from hacker attacks. | 0.78 | ||

| 979 | My behavior has an impact on our cybersecurity. | 0.76 | ||

| 976 | Being constantly attentive to cyber risks when conducting business is not necessary. | 0.72 | ||

| 973 | My behavior can create vulnerabilities that hackers can exploit. | 0.71 | ||

| 970 | My behavior during everyday business activities does not affect the safety of company data. | 0.68 | ||

| 967 | I should always keep careful watch throughout my business activities to protect the company from cyber-attacks. | 0.62 | ||

| 978 | I should be attentive when sending emails and even when entering the company facilities. | 0.62 | ||

| E | I can and should do something in case of a cyber-attack. I am an important part of the response and can be creative to support our customers. | 962 | I should do something in case of a cyber-attack because I am an important part of the response to it. | 0.79 |

| 952 | I should do something in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.73 | ||

| 955 | I am part of the response in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.61 | ||

| 956 | My creativity can be an important part of the response to cyber-attacks. | 0.59 | ||

| 959 | Not only can I, but I also should do something in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.56 | ||

| 1048 | I want to provide information and inputs on my business processes and alternatives in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.56 | ||

| 948 | I am an important part of the response against cyber-attacks. | 0.55 | ||

| 957 | There is not much I can do once a cyber-attack on our company is successful. | 0.55 | ||

| 951 | I am not an essential part of the response to a cyber-attack as there is nothing I can do. | 0.54 | ||

| 950 | To minimize the impact of a cyber-attack, I should know my business partners and their needs. | 0.53 | ||

| F | I know how to respond in case of a cyber-attack and have trained in alternative business processes. | 985 | I have alternative processes in place in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.81 |

| 981 | I feel well prepared for a cyber-attack. | 0.75 | ||

| 989 | The processes to follow in case of a cyber-attack are well known. | 0.70 | ||

| 992 | The company has guidelines in place in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.66 | ||

| 982 | I know how to deal with a cyber-attack. | 0.65 | ||

| 991 | I do not know how to react in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.65 | ||

| 988 | I have trained in cyber responses in the last 12 months. | 0.64 | ||

| 997 | I have trained in alternative business processes I can use in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.62 | ||

| 1004 | We received training on how to respond in case of a cyber-attack. | 0.62 | ||

| 986 | Our company informed us about how to react to cyber-attacks. | 0.61 | ||

| G | We need to learn from cyber-attacks and continue to evolve our preparedness and response. | 1009 | Cyber-attacks are a recurring topic in our company. | 0.82 |

| 1021 | Learning from past cyber-attacks is part of our cybersecurity strategy. | 0.77 | ||

| 1030 | We have learned from past cyber-attacks. | 0.74 | ||

| 1025 | It is essential to learn from past cyber-attacks to be better prepared for the future. | 0.66 | ||

| 1013 | We are informed about the latest developments in cybersecurity. | 0.65 | ||

| 1018 | We have updated our response to cyber-attacks in the last 12 months. | 0.62 | ||

| 1006 | We have regular company updates on cyber-attacks and cybersecurity. | 0.59 | ||

| 1023 | We discuss cyber-attacks in our company. | 0.59 | ||

| 1026 | I am more aware when I receive information on cyber risk/-attacks on a regular basis. | 0.58 | ||

| 1011 | Learning from past or failed cyber-attacks helps to increase our preparedness and response. | 0.54 |

References

- Antunes, Mário, Carina Silva, and Frederico Marques. 2021a. An Integrated Cybernetic Awareness Strategy to Assess Cybersecurity Attitudes and Behaviours in School Context. Applied Sciences 11: 11269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, Mário, Marisa Maximiano, Ricardo Gomes, and Daniel Pinto. 2021b. Information Security and Cybersecurity Management: A Case Study with SMEs in Portugal. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy 1: 219–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biener, Christian, Martin Eling, and Jan Hendrik Wirfs. 2015. Insurability of cyber risk: An empirical analysis. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 40: 131–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björck, Albena, Audra Diers-Lawson, and Felix Dücrey. 2022. Evolution and effectiveness of the governmental risk and crisis communication on Twitter in the COVID-19 pandemic: The Case of Switzerland. Proceedings of the International Crisis and Risk Communication Conference 5: 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björck, Albena, Carlo Pugnetti, and Carlos Casián. 2024. Communicating to Mitigate Behavioral Cyber Risks: The Case of Employee Vulnerability. In Handbook of Communicating Safety and Risk. Edited by Timothy L. Sellnow and Deanna D. Sellnow. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, Ann-Renée, and Elke U. Weber. 2006. A domain-specific risk-taking (DOSPERT) scale for adult populations. Judgment and Decision Making 1: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkovich, Debra J., and Robert J. Skovira. 2020. Working from Home: Cybersecurity in the Age of COVID-19. Issues in Information Systems 21: 234–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, Noel T., Neil D. Weinstein, Cara L. Cuite, and James E. Herrington. 2004. Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 27: l25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Glenn L., and Jerry C. Olson. 2002. Mapping Consumers’ Mental Models with ZMET. Psychology and Marketing 19: 477–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. Timothy. 2009. Crisis, Crisis Communication, Reputation, and Rhetoric. In Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II. New York: Routledge, pp. 249–64. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. Timothy, and Sherry J. Holladay, eds. 2010. Handbook of Crisis Communication. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. xxvi–xxvii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutlee, Christopher G., Cary S. Politzer, Rick H. Hoyle, and Scott A. Huettel. 2014. An Abbreviated Impulsiveness Scale Constructed Through Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale Version 11. Archives of Scientific Psychology 2: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CybSafe. 2020. Human Error to Blame for 9 in 10 UK Cyber Data Breaches in 2019. Available online: https://www.cybsafe.com/press-releases/human-error-to-blame-for-9-in-10-uk-cyber-data-breaches-in-2019/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Damasio, Antonio R. 1989. Time-locked multiregional retroactivation: A systems-level proposal for the neural substrates of recall and recognition. Cognition 33: 25–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, Richard A., Gordon L. Flett, and Avi Besser. 2002. Validation of a New Scale for Measuring Problematic Internet Use: Implications for Pre-employment Screening. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 5: 331–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruijn, Hans, and Marjin Janssen. 2017. Building cybersecurity awareness: The need for evidence-based framing strategies. Government Information Quarterly 34: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egelman, Serge, and Eyal Peer. 2015. Scaling the security wall: Developing a Security Behavior Intentions Scale (SeBIS). Paper presented at CHI’15: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea, April 18–23; pp. 2873–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Agency for Network and Information Security ENISA. 2016. Review of Cyber Hygiene Practices (December 2016). Available online: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/cyber-hygiene/at_download/fullReport (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2022. Internet Crime Report 2021. Available online: https://www.ic3.gov/Media/PDF/AnnualReport/2021_IC3Report.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Frandsen, Finn, and Winni Johansen. 2011. The study of internal crisis communication: Towards an integrative framework. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 16: 247–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisby, Brandi N., Shari R. Veil, and Timothy L. Sellnow. 2014. Instructional Messages During Health-Related Crises: Essential Content for Self-Protection. Health Communication 29: 347–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitzer, Frank L., Justin Purl, D. E. Sunny Becker, Paul J. Sticha, and Yung Mei Leong. 2019. Modeling expert judgments of insider threat using ontology structure: Effects of individual indicator threat value and class membership. Paper presented at 52nd Hawaii International Conference on Systems, Grand Wailea, HI, USA, January 8–11; pp. 3202–11. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10125/59756 (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Hadlington, Lee. 2017. Human factors in cybersecurity; examining the link between Internet addiction, impulsivity, attitudes towards cybersecurity and risky cybersecurity behaviours. Heliyon 3: e00346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadlington, Lee. 2018. Employees Attitude towards Cyber Security and Risky Online Behaviours: An Empirical Assessment in the United Kingdom. International Journal of Cyber Criminology 12: 269–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, Seyed Taghi, Lella Zarei, Ahmad Kalateh Sadati, Najmeh Moradi, Maryam Akbari, Gholamhossin Mehraliary, and Kamran Bagheri Lankarani. 2021. The effect of risk communication on preventive and protective behaviours during the COVID-I9 outbreak: Mediating role of risk perception. BMC Public Health 21: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E. Tory. 1998. Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 30, pp. 1–46. ISBN 067-2601/98. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Security. 2022. Cost of a Data Breach Report 2022. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/reports/data-breach (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Kennison, Sheila K., and Eric Chan-Tin. 2020. Taking Risks with Cybersecurity: Using Knowledge and Personal Characteristics to Predict self-Reported Cybersecurity Behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 546546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jeong-Nam, and Yunna Rhee. 2011. Strategic Thinking about Employee Communication Behavior (ECB) in Public Relations: Testing the Models of Megaphoning and Scouting Effects in Korea. Journal of Public Relations Research 23: 243–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Mikyoung, and Yoonhyeung Choi. 2017. Risk communication: The roles of message appeal and coping style. Social Behavior and Personality 45: 773–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Young. 2018. Enhancing employee communication behaviors for sensemaking and sensegiving in crisis situations: Strategic management approach for effective internal crisis communication. Journal of Communication Management 22: 451–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, David A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0132952610. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield, Robert S., Kimberly Beauchamp, Derek Lane, Deanna D. Sellnow, Timothy L. Sellnow, Steven Venette, and Bethany Wilson. 2014. Instructional Crisis Communication: Connecting Ethnicity and Sex in the Assessment of Receiver-Oriented Message Effectiveness. Journal of Management and Strategy 5: 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yuchong, and Qinghui Liu. 2021. A comprehensive review study of cyber-attacks and cyber security; Emerging trends and recent developments. Energy Reports 7: 8176–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, Birgy, Kaido Kikkas, and Aare Klooster. 2013. The four most-used passwords are love, sex, secret, and god: Password security and training in different user groups. In Human Aspects of Information Security, Privacy, and Trust: First International Conference, HAS 2013, Held as Part of HCI International 2013, Las Vegas, NV, USA, July 21-26, 2013. Proceedings 1. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 276–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzei, Alessandra, and Silvia Ravazzani. 2011. Manager-employee communication during a crisis: The missing link. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 16: 243–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meertens, Ree M., and René Lion. 2008. Measuring an Individual’s tendency to Take Risks: The Risk Propensity Scale. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38: 1506–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mileti, Dennis S., and Lori Peek. 2000. The social psychology of public response to warnings of a nuclear power plant accident. Journal of Hazardous Materials 75: 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Steve. 2020. Cybercrime to Cost the World $10.5 Trillion Annually By 2025. Northport: Cybercrime Magazine. Available online: https://cybersecurityventures.com/cybercrime-damage-costs-10-trillion-by-2025/ (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Ng, Boon-Yuen, Atreyi Kankanhalli, and Yunjie C. Xu. 2009. Studying users’ computer security behavior: A health belief perspective. Decision Support Systems 46: 815–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, Julie M., and Timothy L. Sellnow. 2009. Reducing Organizational Risk through Participatory Communication. Journal of Applied Communication Research 37: 349–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Jerry C., and Thomas J. Reynolds, eds. 1983. Understanding consumers’ cognitive structures: Implications for advertising strategy. In Advertising and Consumer Psychology. Lexington: Lexington Books, pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Kathryn, Agata McCormac, Marcus Butavicius, Malcolm Pattinson, and Cate Jerram. 2014. Determining employee awareness using the Human Aspects of Information Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q). Computers & Security 42: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proofpoint. 2023. State of the Phish 2023. Available online: https://www.proofpoint.com/us/resources/threat-reports/state-of-phish (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Prümmer, Julia, Tommy van Stehen, and Bibi van den Berg. 2024. A systematic review of current cybersecurity training methods. Computers & Security 136: 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnetti, Carlo, and Carlos Casián. 2021. Cyber Risks and Swiss SMEs: An Investigation of Employees’ Attitudes and Behavioral Vulnerabilities. Winterthur: ZHAW School of Management and Law. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugnetti, Carlo, and Xavier Bekaert. 2018. A Tale of Self-Doubt and Distrust. Onboarding Millennials: Understanding the Experience of New Insurance Customers. Winterthur: ZHAW School of Management and Law. ISBN 978-3-03870-021-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pugnetti, Carlo, Pedro Henriques, and Ulrich Moser. 2022. Goal Setting, Personality Traits, and the role of Insurers and Other Service Providers for Swiss Millennials and Generation Z. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 15: 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, Irwin M. 1974. The Health Belief Model and Preventive Health Behavior. Health Education Monographs 2: 354–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucier, Gerard. 1994. Mini-Markers: A brief version of Goldberg’s unipolar Big-Five markers. Journal of Personality Assessment 63: 506–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenherr, Jordan Richard, and Robert Thomson. 2020. Insider Threat Detection: A Solution in Search of a Problem. Paper presented at IEEE 2020 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security), Dublin, June 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenherr, Jordan Richard, and Robert Thomson. 2021. The Cybersecurity (CSEC) Questionnaire: Individual Differences in Unintentional Insider Threat Behaviours. Paper presented at IEEE 2021 International Conference on Cyber Security Awareness, Data Analytics and Assessment (CyberSA), Dublin, June 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebescen, Nina, and Jessica Vitak. 2017. Securing the Human: Employee Security Vulnerability Risk in Organizational Settings. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 68: 2237–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeger, Matthew W. 2006. Best Practices in Crisis Communication: An Expert Panel Process. Journal of Applied Communication Research 34: 232–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow, Deanna D., Bengt Johansson, Timothy L. Sellnow, and Derek R. Lane. 2019. Toward a global understanding of the effects of the IDEA model for designing instructional risk and crisis messages: A food contamination experiment in Sweden. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 27: 102–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow, Deanna D., Derek Lane, Robert S. Littlefield, Timothy L. Sellnow, Bethany Wilson, Kimberly Beauchamp, and Steven Venette. 2015. A Receiver-Based Approach to Effective Instructional Crisis Communication: Instructional Crisis Communication. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 25: 149–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow-Richmond, Deborah, Amiso George, and Deanna D. Sellnow. 2018. An IDEA model analysis of instructional risk communication in the time of Ebola. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research 1: 135–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellnow, Timothy L., and Deanna D. Sellnow. 2013. The role of instructional risk messages in communicating about food safety. Food Insight: Current Topics in Food Safety and Nutrition 3. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/9111360/The_Role_of_Instructional_Risk_Messages_in_Communicating_about_Food_Safety_The_IDEA_Model (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Sitkin, Sim B., and Amy L. Pablo. 1992. Reconceptualizing the Determinants of Risk Behavior. Academy of Management Review 17: 9–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, Paul. 1987. Perception of Risk. Science 236: 280–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, Jeffrey M., Kathryn R. Stam, Paul Mastrangelo, and Jeffrey Jolton. 2005. Analysis of end user security behaviors. Computers & Security 24: 124–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, Paul, Debora Jeske, Joseph Onibokun, Lynne Coventry, Jurjen Jansen, and Petko Kusev. 2017. Risk perceptions of cyber-security and precautionary behaviour. Computers in Human Behavior 75: 547–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, Arun, Loo Seng Neo, Pamela Goh, Seyoung Lee, Majeed Khader, Gabriel Ong, and Jeffery Chin. 2020. Cyber hygiene: The concept, its measure, and its initial tests. Decision Support Systems 128: 113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Elke U., Ann-Renée Blais, and Nancy E. Betz. 2002. A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 15: 263–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Ryan. 2008. The psychology of security. Communications of the ACM 51: 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Ryan, Christopher Mayhorn, Jefferson Hardee, and Jeremy Mendel. 2009. The Weakest Link: A Psychological Perspective on Why Users Make Poor Security Decisions. In Social and Human Elements of Information Security: Emerging Trends and Countermeasures. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Whitty, Monica, James Doodson, Sadie Creese, and Duncan Hodges. 2015. Individual differences in cyber security behaviors: An examination of who is sharing passwords. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. 2022. Global Cybersecurity Outlook 2022. Geneva: Insight Report. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Wei, Finbarr Murphy, Xian Xu, and Wenpeng Xing. 2021. Dynamic communication and perception of cyber risk: Evidence from big data in media. Computers in Human Behavior 122: 106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaltman, Gerald. 1997. Rethinking Marketing Research: Putting People Back In. Journal of Marketing Research 34: 424–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaltman, Gerald, and Lindsey H. Zaltman. 2008. Marketing Metaphoria: What Deep Metaphors Reveal about the Minds of Consumers. Boston: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Don C., Scott Highhouse, and Christopher D. Nye. 2018. Development and validation of the General Risk propensity Scale (GRiPS). Behavioral Decision Making 32: 152–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xiaochen Angela, and Jonathan Borden. 2020. How to communicate cyber-risk? An examination of behavioral recommendations in cybersecurity crises. Journal of Risk Research 23: 1336–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, Marvin, Sybil B. Eysenck, and Hans J. Eysenck. 1978. Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age and sex comparisons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 46: 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors and Year | Method | Focus | Key Takeaways |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Ng et al. 2009) | Adapted health belief model | Email security behavior | Training to reinforce employee confidence |

| (Parsons et al. 2014) | Human Aspects of Information Security Questionnaire (HAIS-Q) | Link between knowledge, attitude, and behavior | Influence attitude to impact behavior |

| (Sebescen and Vitak 2017) | Self-assessment of behavior, expert risk scoring | Four dimensions of vulnerability and three sets of employee characteristics | Compliance with security policies does not imply lower risk |

| (Hadlington 2017) | Risky cybersecurity behaviors scale (RScB), attitudes towards cybersecurity and cybercrime questionnaire (ATC-IB) | Cybersecurity behavior links to addiction, impulsivity, and attitude | Attitude and behavior are linked. Risky behaviors are widespread |

| (Kennison and Chan-Tin 2020) | Self-reported engagement in six common risky behaviors | Cybersecurity behavior link to knowledge, personality traits, and general risk-taking | Consider personal profiles when estimating threat levels |

| (Schoenherr and Thomson 2021) | Vulnerability operationalized by usage of social media and frequency of computer use | Unintentional cyber behavior based on individual traits and motivation | Prospective gains and losses are linked to risk behavior |

| Underwriting questionnaires from insurance carriers and brokers | Focus shift from technical infrastructure to behavioral risk | ||

| Threat assessment from law enforcement/security agencies | Confidential/not peer-reviewed | ||

| Element and Description |

|---|

| Internalization focuses on the recipient itself and relates to the emotional part of risk messaging. It highlights the personal relevance, potential impact, proximity, and timeliness, leading to an increased motivation to attend to the message. |

| Distribution deals with the choice of adequate communication channels for the message. Depending on the crisis’s dimension, multiple channels may need to be used to ensure it reaches all target audiences. |

| Explanation covers crisis-related information, such as the current situation and the underlying reason. The information needs to come from credible sources and must be formulated in the language of the affected audience. |

| Action delivers instructions on how recipients can protect themselves from the threat. These messages must be stated in a precise and understandable way so that the audience can act upon them. |

| Internalized To-Be Messages | |

|---|---|

| A | My company and I have valuable information, we are targeted by hackers, and we need to protect ourselves. |

| B | We can make mistakes, and we need to continue our business activities with better risk awareness. |

| C | I have a responsibility to do something. |

| D | I have to protect the company with my behavior during regular business activities. |

| E | I can and should do something in case of a cyber-attack. I am an important part of the response and can be creative to support our customers. |

| F | I know how to respond in case of a cyber-attack and have trained in alternative business processes. |

| G | We need to learn from cyber-attacks and continue to evolve our preparedness and response. |

| Construct/Question | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | ALL | A | 911 | 914 | 891 | 916 | 908 |

| Mobiliar p-value | 0.58 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.94 |

| SME p-value | 0.05 | <0.01 | 0.05 | 0.32 | 0.01 | <0.01 | 0.02 |

| ID | B | 929 | 925 | 1035 | 933 | 927 | |

| Mobiliar p-value | 0.09 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 0.74 | 0.35 | 0.22 | |

| SME p-value | 0.57 | 0.30 | 0.72 | 0.47 | 0.01 | 0.11 | |

| ID | C | 942 | 939 | 937 | 944 | 947 | |

| Mobiliar p-value | 0.70 | 0.28 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 0.10 | |

| SME p-value | 0.04 | <0.01 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.62 | |

| ID | D | 966 | 977 | 964 | 972 | 979 | |

| Mobiliar p-value | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.88 | 0.76 | |

| SME p-value | 0.01 | 0.10 | <0.01 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| ID | E | 962 | 952 | 955 | 956 | 959 | |

| Mobiliar p-value | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.96 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.17 | |

| SME p-value | 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 0.29 | 0.65 | 0.83 | |

| ID | F | 985 | 981 | 989 | 992 | 991 | |

| Mobiliar p-value | 0.58 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.17 | |

| SME p-value | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.63 | 0.17 | |

| ID | G | 1009 | 1021 | 1030 | 1025 | 1013 | |

| Mobiliar p-value | 0.67 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 0.68 | 0.20 | |

| SME p-value | 0.61 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.99 | |

| Legend: p-value | ≤0.10 | ≤0.05 | ≤0.01 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pugnetti, C.; Björck, A.; Schönauer, R.; Casián, C. Towards Diagnosing and Mitigating Behavioral Cyber Risks. Risks 2024, 12, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12070116

Pugnetti C, Björck A, Schönauer R, Casián C. Towards Diagnosing and Mitigating Behavioral Cyber Risks. Risks. 2024; 12(7):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12070116

Chicago/Turabian StylePugnetti, Carlo, Albena Björck, Reto Schönauer, and Carlos Casián. 2024. "Towards Diagnosing and Mitigating Behavioral Cyber Risks" Risks 12, no. 7: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12070116

APA StylePugnetti, C., Björck, A., Schönauer, R., & Casián, C. (2024). Towards Diagnosing and Mitigating Behavioral Cyber Risks. Risks, 12(7), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks12070116