In Vivo Experimental Endovascular Uses of Cyanoacrylate in Non-Modified Arteries: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Outcomes

3. Results

3.1. Included Studies

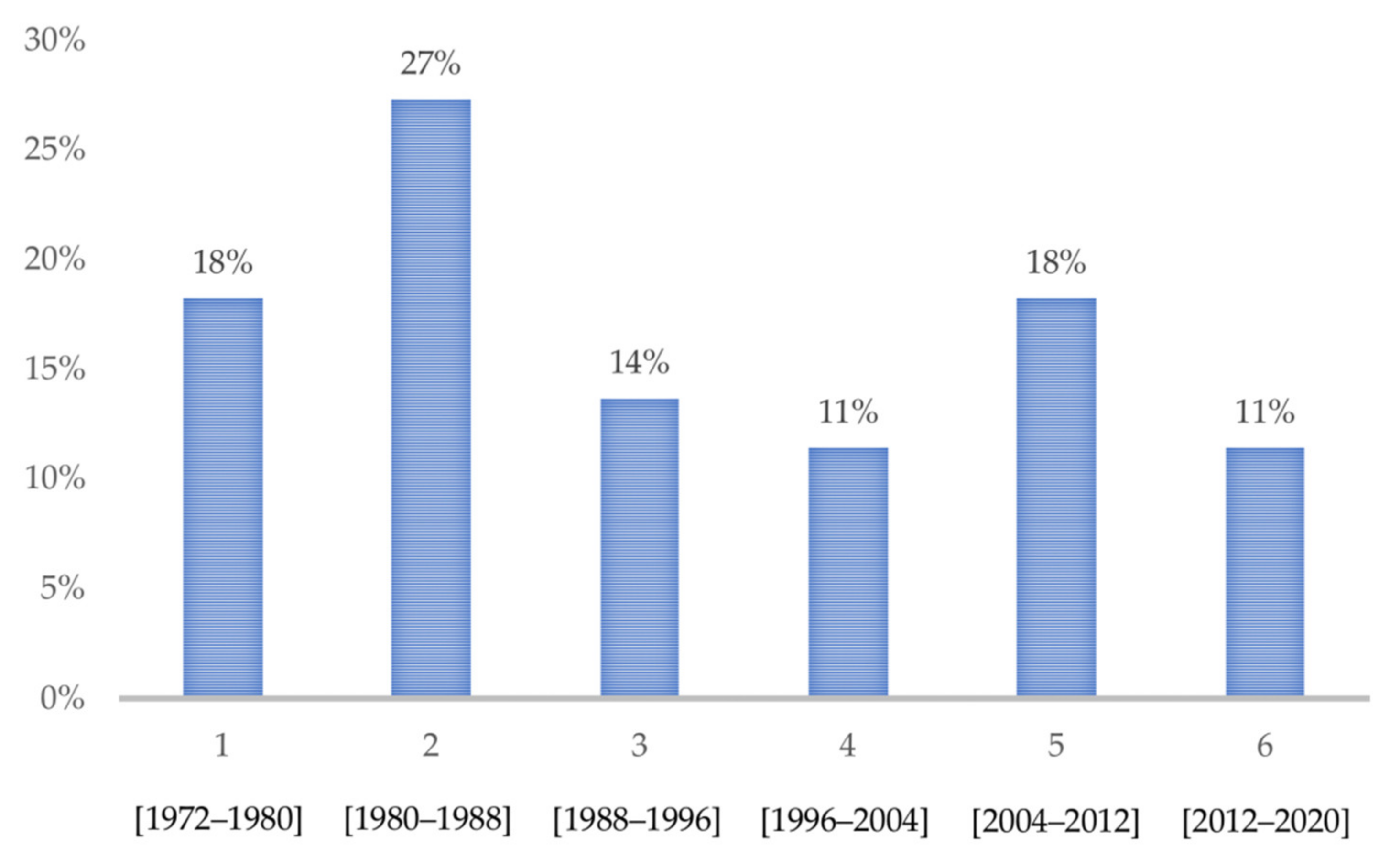

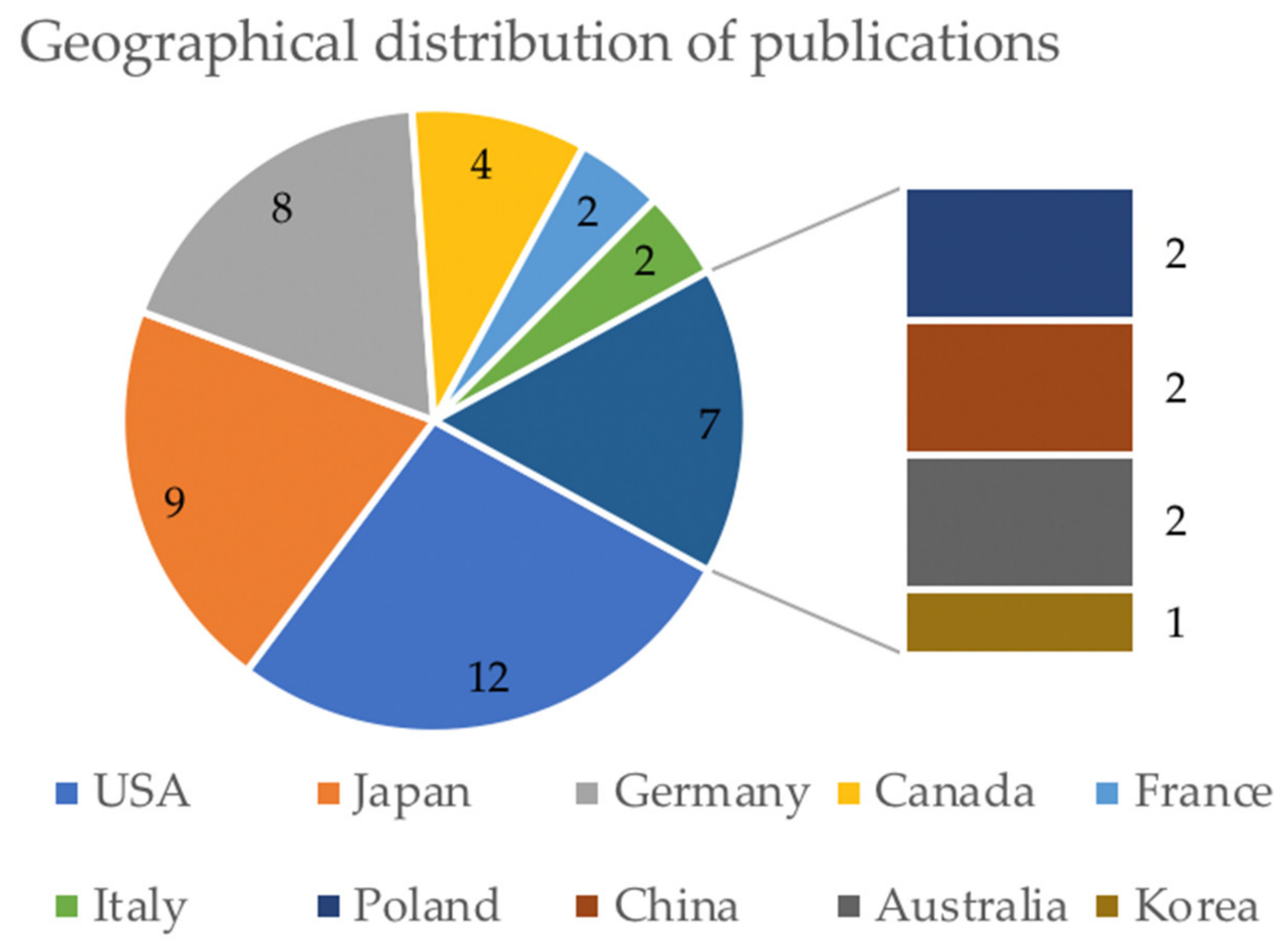

3.2. General Characteristics

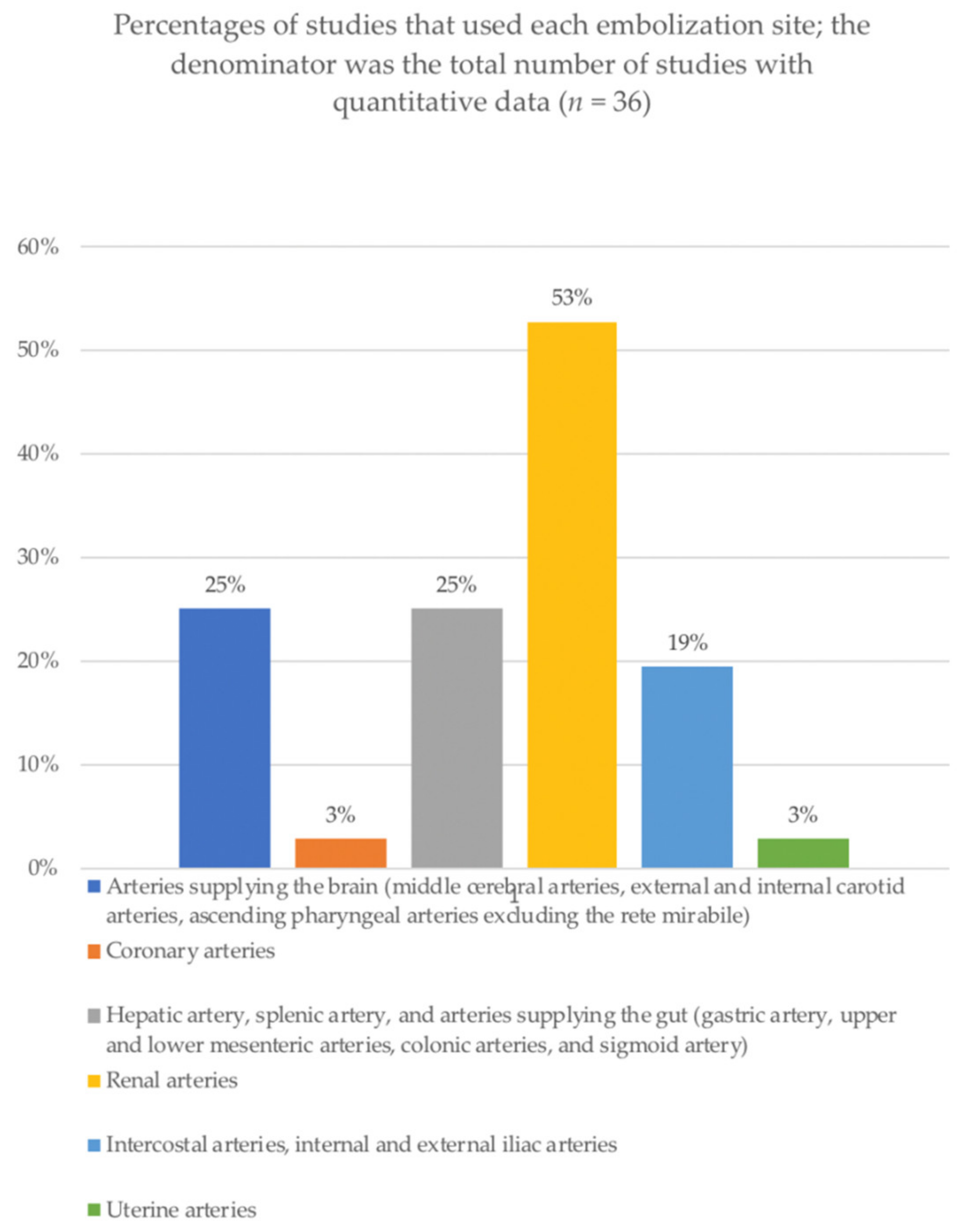

3.3. Procedures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.J.; Barthes-Biesel, D.; Salsac, A.V. Polymerization kinetics of n-butyl cyanoacrylate glues used for vascular embolization. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 69, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouzeghrane, F.; Naggara, O.; Kallmes, D.F.; Berenstein, A.; Raymond, J. In vivo experimental intracranial aneurysm models: A systematic review. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2010, 31, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murayama, Y.; Vinuela, F.; Ulhoa, A.; Akiba, Y.; Duckwiler, G.; Gobin, Y.; Vinters, H.V.; Greff, R.J. Nonadhesive liquid embolic agent for cerebral arteriovenous malformations: Preliminary histopathological studies in swine rete mirabile. Neurosurgery 1998, 43, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greim-Kuczewski, K.; Berenstein, A.; Kis, S.; Hauser, A.; Killer-Oberpfalzer, M. Surgical technique for venous patch aneurysms with no neck in a rabbit model. J. Neurointervent. Surg. 2018, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennecka, C.R.; Preul, M.C.; Bichard, W.D.; Vernon, B.L. In vivo experimental aneurysm embolization in a swine model with a liquid-to-solid gelling polymer system: Initial biocompatibility and delivery strategy analysis. World Neurosurg. 2012, 78, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbacher, S.; Erhardt, S.; Schläppi, J.A.; Coluccia, D.; Remonda, L.; Fandino, J.; Sherif, C. Complex bilobular, bisac cular, and broad-neck microsurgical aneurysm formation in the rabbit bifurcation model for the study of upcoming endovascular techniques. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2011, 32, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nakai, M.; Ikoma, A.; Loffroy, R.; Midulla, M.; Kamisako, A.; Higashino, N.; Fukuda, K.; Sonomura, T. Type II endoleak model creation and intraoperative aneurysmal sac embolization with n-butyl cyanoacrylate-lipiodol-ethanol mixture (NLE) in swine. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2018, 8, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, P.H.; Sherman, F.E. Experimental evaluation of a tissue adhesive as an agent for the treatment of aneurysms and arteriovenous anomalies. J. Neurosurg. 1972, 36, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abdulmalak, G.; Chevallier, O.; Falvo, N.; Di Marco, L.; Bertaut, A.; Moulin, B.; Abu-Khalil, C.; Gehin, S.; Charles, P.E.; Latournerie, M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of transcatheter embolization with Glubran® 2 cyanoacrylate glue for acute arterial bleeding: A single-center experience with 104 patients. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loffroy, R.; Comby, P.O.; Guillen, K.; Salsac, A.V. N-butyl cyanoacrylate-Lipiodol mixture for endovascular purpose: Polymerization kinetics differences between in vitro and in vivo experiments. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2020, 43, 1409–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Liao, J.; Preston, J.; Batjer, H. A canine model of acute hindbrain ischemia and reperfusion. Neurosurgery 1995, 36, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, G.F.; Hammadeh, R.; Francois, C.; McCarthy, R.; Leya, F. Controlled myocardial infarction induced by intracoronary injection of n-butyl cyanoacrylate in dogs: A feasibility study. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2005, 66, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae, H.J.; Chung, J.W.; Kim, H.C.; So, Y.H.; Lim, H.G.; Lee, W.; Kim, B.K.; Park, J.H. Experimental study on acute ischemic small bowel changes induced by superselective embolization of superior mesenteric artery branches with N-butyl cyanoacrylate. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2008, 19, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotter, C.T.; Goldman, M.L.; Rösch, J. Instant selective arterial occlusion with isobutyl 2-cyanoacrylate. Radiology 1975, 114, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takasawa, C.; Seiji, K.; Matsunaga, K.; Matsuhashi, T.; Ohta, M.; Shida, S.; Takase, K.; Takahashi, S. Properties of N-butyl cyanoacrylate-iodized oil mixtures for arterial embolization: In vitro and in vivo experiments. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2012, 23, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromwell, L.D.; Freeny, P.C.; Kerber, C.W.; Kunz, L.L.; Harris, A.B.; Shaw, C.M. Histologic analysis of tissue response to bucrylate-pantopaque mixture. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1986, 147, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, S.M.; Vinuela, F.; Goldwasser, J.M.; Fox, A.J.; Pelz, D.M. Adjusting the polymerization time of isobutyl-2 cyanoacrylate. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1986, 7, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sadato, A.; Wakhloo, A.K.; Hopkins, L.N. Effects of a mixture of a low concentration of N-butylcyanoacrylate and ethiodol on tissue reactions and the permanence of arterial occlusion after embolization. Neurosurgery 2000, 47, 1197–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmigielski, W.; Klamut, M.; Wolski, T.; Studnicki, W.; Rubaj, B. Urogranoic acid as a radiopaque additive to the cyanoacrylic adhesive in transcatheter obliteration of renal arteries. Investig. Radiol. 1981, 16, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oowaki, H.; Matsuda, S.; Sakai, N.; Ohta, T.; Iwata, H.; Sadato, A.; Taki, W.; Hashimoto, N.; Ikada, Y. Non-adhesive cyanoacrylate as an embolic material for endovascular neurosurgery. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrun, G.M.; Vinuela, F.V.; Fox, A.J.; Kan, S. Two different calibrated-leak balloons: Experimental work and application in humans. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1982, 3, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Khangure, M.S.; Ap Simon, H.T.; Chakera, T.M.; Hartley, D.E. A catheter system for the safe and efficient delivery of tissue glues (bucrylate) for visceral embolization. Br. J. Radiol. 1981, 54, 671–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ApSimon, H.T.; Hartley, D.E.; Maddren, L.; Harper, C. Embolization of small vessels with a double-lumen microballoon catheter. Part II: Laboratory, animal, and histological studies. Work in progress. Radiology 1984, 151, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoesslein, F.; Ditscherlein, G.; Romaniuk, P.A. Experimental studies on new liquid embolization mixtures (histoacryl-lipiodol, histoacryl-panthopaque). Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 1982, 5, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izaaryene, J.; Saeed Kilani, M.; Rolland, P.H.; Gaubert, J.Y.; Jacquier, A.; Bartoli, J.M.; Vidal, V. Preclinical study on an animal model of a new non-adhesive cyanoacrylate (Purefill®) for arterial embolization. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2016, 97, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F.; Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Minamiguchi, H.; Nakai, M.; Nakata, K.; Sanda, H.; Sonomura, T.; Matuzaki, I.; Murata, S. Effect of transcatheter arterial embolization with a mixture of n-butyl cyanoacrylate, lipiodol, and ethanol on the vascular wall: Macroscopic and microscopic studies. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2015, 33, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaguchi, S.; Lohman, B.D.; Ogawa, Y.; Arai, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Matsumoto, J.; Nakajima, Y. Preliminary findings of arterial embolization with balloon-occluded and flow-dependent histoacryl glue embolization in a swine model. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2015, 33, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, R.S.; Distelmaier, M.S.; Hellmann-Sokolis, M.; Naami, A.; Kuhl, C.K.; Hohl, C. Early detection of acute mesenteric ischemia using diffusion-weighted 3.0-T magnetic resonance imaging in a porcine model. Investig. Radiol. 2013, 48, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonomura, T.; Kawai, N.; Ikoma, A.; Minamiguchi, H.; Ozaki, T.; Kishi, K.; Sanda, H.; Nakata, K.; Nakai, M.; Muragaki, Y.; et al. Uterine damage in swine following uterine artery embolization: Comparison among gelatin sponge particles and two concentrations of N-butyl cyanoacrylate. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2013, 31, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Yamaguchi, M.; Takahashi, T.; Izaki, K.; Uotani, K.; Sakamoto, N.; Sugimura, K.; Sugimoto, K. Is embolization of the pancreas safe? Pancreatic histological changes after selective transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate in a swine model. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2012, 35, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Ikoma, A.; Nakata, K.; Sanda, H.; Minamiguchi, H.; Nakai, M.; Sonomura, T.; Mori, I. Safety of bronchial arterial embolization with n-butyl cyanoacrylate in a swine model. World J. Radiol. 2012, 4, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikoma, A.; Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Sonomura, T.; Minamiguchi, H.; Nakai, M.; Takasaka, I.; Nakata, K.; Sahara, S.; Sawa, N.; et al. Ischemic effects of transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate-lipiodol on the colon in a swine model. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2010, 33, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonemitsu, T.; Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Sonomura, T.; Takasaka, I.; Nakai, M.; Minamiguchi, H.; Sahara, S.; Iwasaki, Y.; Naka, T.; et al. Comparison of hemostatic durability between N-butyl cyanoacrylate and gelatin sponge particles in transcatheter arterial embolization for acute arterial hemorrhage in a coagulopathic condition in a swine model. Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 2010, 33, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levrier, O.; Mekkaoui, C.; Rolland, P.H.; Murphy, K.; Cabrol, P.; Moulin, G.; Bartoli, J.M.; Raybaud, C. Efficacy and low vascular toxicity of embolization with radical versus anionic polymerization of n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA). An experimental study in the swine. J. Neuroradiol. 2003, 30, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, H.M.; Klosterhalfen, B.; Kinzel, S.; Jansen, A.; Seggewiss, C.; Weghaus, P.; Kamp, M.; Töns, C.; Günther, R.W. CT and MRI of experimentally induced mesenteric ischemia in a porcine model. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 1996, 20, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widlus, D.M.; Lammert, G.K.; Brant, A.; Tsue, T.; Samphilipo, M.A., Jr.; Magee, C.; Starr, F.L.; Anderson, J.H.; White, R.I., Jr. In vivo evaluation of iophendylate-cyanoacrylate mixtures. Radiology 1992, 185, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brothers, M.F.; Kaufmann, J.C.; Fox, A.J.; Deveikis, J.P. N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate--substitute for IBCA in interventional neuroradiology: Histopathologic and polymerization time studies. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1989, 10, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miller, F.J.J.; Rankin, R.S.; Gliedman, J.B. Experimental internal iliac artery embolization: Evaluation of low viscosity silicone rubber, isobutyl 2-cyanoacrylate, and carbon microspheres. Radiology 1978, 129, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.M.; Cheng, L.F.; Li, N. Histopathological study of vascular changes after intra-arterial and intravenous injection of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. Chin. J. Dig. Dis 2006, 7, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, T.; Chu, M.; Bao, D. Experimental study of Eudragit mixture as a new nonadhesive liquid embolic material. Chin. Med. J. 2002, 115, 555–558. [Google Scholar]

- Gounis, M.J.; Lieber, B.B.; Wakhloo, A.K.; Siekmann, R.; Hopkins, L.N. Effect of glacial acetic acid and ethiodized oil concentration on embolization with N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate: An in vivo investigation. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 938–944. [Google Scholar]

- Salomonowitz, E.; Gottlob, R.; Castaneda-Zuniga, W.; Amplatz, K. Work in progress: Transcatheter embolization with cyanoacrylate and nitrocellulose. Radiology 1983, 149, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, R.; Schubert, U.; Bohl, J.; Georgi, M.; Marberger, M. Transcatheter embolization of the kidney with butyl-2-cyanoacrylate: Experimental and clinical results. Cardiovasc. Radiol. 1978, 1, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.; Berthelet, F.; Desfaits, A.C.; Salazkin, I.; Roy, D. Cyanoacrylate embolization of experimental aneurysms. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Donnan, G.A.; Davis, S.M. Stroke drug development: Usually, but not always, animal models. Stroke 2005, 36, 2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shuster, A.; Gunnarsson, T.; Klurfan, P.; Larrazabal, R. N-butyl cyanoacrylate proved beneficial to avoid a nontarget embolization of the ophthalmic artery in endovascular management of epistaxis. A neurointerventional report and literature review. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2011, 17, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C.; Zetterlund, P.B.; Aldabbagh, F. Radical polymerization of alkyl 2-cyanoacrylates. Molecules 2018, 23, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almeida, J.I.; Javier, J.J.; Mackay, E.G.; Bautista, C.; Cher, D.J.; Proebstle, T.M. Thirty-sixth-month follow-up of first-in-human use of cyanoacrylate adhesive for treatment of saphenous vein incompetence. J. Vasc. Surg. Venous Lymphat. Disord. 2017, 5, 658–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Barthes-Biesel, D.; Salsac, A.V. Polymerization kinetics of a mixture of Lipiodol and Glubran 2 cyanoacrylate glue upon contact with a proteinaceous solution. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 74, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, A.J.; Smith, L.A.; Morris, A.J. Use of hemostatic powder (Hemospray) in the management of refractory gastric variceal hemorrhage. Endoscopy 2013, 45, E86–E87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kawai, N.; Sato, M.; Minamiguchi, H.; Ikoma, A.; Sanda, H.; Nakata, K.; Tanaka, F.; Nakai, M.; Sonomura, T. Basic study of a mixture of N-butyl cyanoacrylate, ethanol, and lipiodol as a new embolic material. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2012, 23, 1516–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollherbst, D.F.; Otto, R.; Hantz, M.; Ulfert, C.; Kauczor, H.U.; Bendszus, M.; Sommer, C.M.; Möhlenbruch, M.A. Investigation of a new version of the liquid embolic agent PHIL with extra-low-viscosity in an endovascular embolization model. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1696–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoud, T.; Ji, C.; Vinuela, F.; Turjman, F.; Guglielmi, G.; Duckwiler, G.; Gobin, Y.P. Laboratory simulations and training in endovascular embolotherapy with a swine arteriovenous malformation model. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 1996, 17, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grunwald, I.Q.; Romeike, B.; Eymann, R.; Roth, C.; Struffert, T.; Reith, W. An experimental aneurysm model: A training model for neurointerventionalists. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2006, 12, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carmignani, G.; Belgrano, E.; Puppo, P. Evaluation of different types of emboli in transcatheter embolization of rat kidney. Urol Res. 1977, 5, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmignani, G.; Belgrano, E.; Puppo, P.; Giuliani, L. Cyanoacrylates in transcatheter renal embolization. Acta Radiol. Diagn. 1978, 19, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, M.; Cenni, P.; Simonetti, L.; Bozzao, A.; Romano, A.; Bonamini, M.; Fantozzi, L.M.; Fini, G. Glubran 2®: A new acrylic glue for neuroradiological endovascular use: A complementary histological study. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2003, 9, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cyanoacrylate Glue Used | Radiopaque Agent | Other Components | Absolute Cyanoacrylate Concentration (%) | Amount (mL) | Embolization Site | Microcatheter Distal Tip-External Diameter (French) | Introducer Size (French) | Authors | Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial cyanoacrylate | None | None | 0.96 | 0.05 | Superior cerebral artery and anterior communicating artery | DP | DP | Guo et al. [13] | 1995 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Ethiodized oil | Tantalum powder | 0.17–0.33 | 0.5–1 | Coronary artery | NR | 7.0 | Matos et al. [14] | 2005 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.25 | 0.1–0.3 | Superior mesenteric artery | 3.0 | 5.0 | Jae et al. [15] | 2008 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Tantalum powder alone | None | 1 | 0.3–0.5 | Left gastric artery, gastroduodenal artery, inferior pancreatico-duodenal artery, and branches of the superior mesenteric artery | 3.0 | 6.7 | Dotter et al. [16] | 1975 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.1–0.5 | 0.43 | Renal artery | 2.0 | 8.0 | Takasawa et al. [17] | 2012 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Iophendylate oil | None | 0.5 | NR | Renal artery | DP | DP | Cromwell et al. [18] | 1986 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Iophendylate oil | Tantalum powder, Glacial acetic acid | 0.75 | NR | Renal artery and polar arteries | 3.6–4.2 | 7.0 | Spiegel et al. [19] | 1986 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Tantalum powder alone | With or without nitrocellulose | 0.96–1 | 4–5.4 | Renal artery | 3.0 | 5.0 | Sadato et al. [20] | 2000 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol, Urogranoic acid | None | 0.33–0.7 | 0.5-2 | Renal artery and polar arteries | 3.0 | DI | Szmigielski et al. [21] | 1981 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Tantalum powder alone | None | 0.11–0.26 | NR | Renal artery | 3.6 | NR | Oowaki et al. [22] | 2000 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | None | None | 1 | 0.15 | Left renal artery | 1.5–2.6 | NR | Zanetti et al. [8] | 1972 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Iophendylate oil | Tantalum powder | 0.75 | NR | Branch of renal artery, branch of external carotid artery, and vertebral artery | 3.6–4.2 | 7.0 | Debrun et al. [23] | 1982 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Iophendylate oil | None | 0.5 | NR | Renal and visceral arteries | 1.0 | 6.5 | Khangure et al. [24] | 1981 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Iophendylate oil | Tantalum powder | 0.75 | 0.13 | Renal artery, splenic artery, and anterior spinal artery via the vertebral artery | 3.0 | 4.1–5.0 | ApSimon et al. [25] | 1984 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Iophendylate oil, Lipiodol | None | 0.2–0.5 | NR | Renal artery, intercostal and lumbar arteries, vertebral arteries, and superior mesenteric artery | NR | 5.0 | Stoesslein et al. [26] | 1982 |

| Cyanoacrylate Glue Used | Radioopaque Agent | Other Components | Absolute Cyanoacrylate Concentration (%) | Amount (mL) | Embolization Site | Microcatheter Distal Tip-External Diameter (French) | Introducer Size (French) | Authors | Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-hexil-cyanoacrylate | Lipiodol | None | 0.33 | NR | Renal artery and polar arteries (ascending pharyngeal artery and rete mirabile) | 2.4 | 6.0 | Izaaryene et al. [27] | 2016 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.5 | NR | Common hepatic artery and internal inguinal artery | 2.2 | 5.0 | Tanaka et al. [28] | 2015 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.5 | 0.3–0.7 | Intercostal artery | 2.7 | 4.0 | Hamaguchi et al. [29] | 2015 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.67 | 0.5 | Superior mesenteric artery or one of its main branches | 2.9 | 6.0 | Bruhn et al. [30] | 2013 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.13–0.5 | 0.11–0.16 | Uterine artery | 2.2 | 4.0 | Sonomura et al. [31] | 2013 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.5–0.1 | 0.67 | Dorsal pancreatic artery | 2.1 | 5.0 | Okada et al. [32] | 2012 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.125 | 0.2 | Bronchial artery | 2.5 | 4.0 | Tanaka et al. [33] | 2012 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.2 | 0.1–0.4 | Sigmoid-rectal branch artery, right colic branch, and middle colic branch | 2.5 | 5.0 | Ikoma et al. [34] | 2010 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.17 | NR | Renal and splenic arteries | 2.5 | 5.0 | Yonemitsu et al. [35] | 2010 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.5–0.22 | 0.2 | Renal arterial branches and ascending pharyngeal artery | 2.0–2.6 | 5.0 | Levrier et al. [36] | 2003 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.5 | 5 | Superior mesenteric artery | 3.0 | 8.0 | Klein et al. [37] | 1996 |

| Avacryl® (NBCA) | Iophendylate oil | None | 0.2–0.5 | 0.2–0.05 | Renal artery, hepatic artery, gastro-splenic artery, internal iliac artery, gluteal artery, posterior and anterior deep femoral arteries, popliteal artery, anterior tibial artery, and jejunal artery | 3.0 | 7.0 | Widlus et al. [38] | 1992 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Iophendylate oil | Glacial acetic acid | 0.50–0.75 | 0.15 | Internal carotid artery (rete mirabile) | 4.1 | 5.0 | Brothers et al. [39] | 1989 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Tantalum powder alone | Tantalum powder | 0.1 | 3.3 | Internal iliac artery | 3.5 | 7.0 | Miller et al. [40] | 1978 |

| Cyanoacrylate Glue Used | Radiopaque Agent | Other Components | Absolute Cyanoacrylate Concentration (%) | Amount (mL) | Embolization Site | Microcatheter Distal Tip-External Diameter (French) | Introducer Size (French) | Authors | Publication Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.5 | 0.1–0.2 | Femoral artery | DP | DP | Wang et al. [41] | 2006 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Iobenzene ester | None | 0.5 | 0.2–0.3 | Right carotid artery | 2.0–2.7 | DI | Shi et al. [42] | 2002 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | Glacial acetic acid | 0.2–0.5 | NR | Subclavian and femoral arteries | 1.8–2.7 | 4.0 | Gounis et al. [43] | 2002 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Ethiodol | Ethiodol | 0.5–0.2 | 0.2 | Renal artery | 2.7 | DI | Sadato et al. [20] | 2000 |

| Isostearyl-2-cyanoacrylate (derived from IBCA), Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Lipiodol | None | 0.5 | 0.5 | Renal artery | 1.5 | NR | Oowaki et al. [22] | 1999 |

| Bucrylate® (IBCA) | Tantalum powder alone | With or without nitrocellulose | 0.96–0.99 | 0.4–0.8 | Renal artery | 3.0 | DI | Salomonowitz et al. [44] | 1983 |

| Histoacryl® (NBCA) | Tantalum powder alone | None | 0.11–0.25 | NR | Renal artery | 3.0–3.6 | NR | Günther et al. [45] | 1978 |

| Histopathologic Findings | Minimal Delay between Embolization and Description (Days) | Animal Models |

|---|---|---|

| Sponge-like matrix with entrapped erythrocytes in its interstices | 1 | Swine, dog, rabbit |

| Desquamation of adjacent to the endothelial cells | 1 | Swine, dog |

| Infiltration of neutrophils into the adventitial layer | 1 | Dog |

| Infiltration of neutrophils into the intermediate layer | 2 | Swine, rat |

| Hyperplasia of adjacent elastic fibrils | 7 | Dog |

| Foreign body giant cells adjacent to the polymer | 7 | Swine, dog, rabbit, rat |

| Tissue necrosis | 7 | Swine, dog, rabbit, rat |

| Infarcted region calcification | 21 | Rabbit |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guillen, K.; Comby, P.-O.; Chevallier, O.; Salsac, A.-V.; Loffroy, R. In Vivo Experimental Endovascular Uses of Cyanoacrylate in Non-Modified Arteries: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9091282

Guillen K, Comby P-O, Chevallier O, Salsac A-V, Loffroy R. In Vivo Experimental Endovascular Uses of Cyanoacrylate in Non-Modified Arteries: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines. 2021; 9(9):1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9091282

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuillen, Kévin, Pierre-Olivier Comby, Olivier Chevallier, Anne-Virginie Salsac, and Romaric Loffroy. 2021. "In Vivo Experimental Endovascular Uses of Cyanoacrylate in Non-Modified Arteries: A Systematic Review" Biomedicines 9, no. 9: 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9091282

APA StyleGuillen, K., Comby, P.-O., Chevallier, O., Salsac, A.-V., & Loffroy, R. (2021). In Vivo Experimental Endovascular Uses of Cyanoacrylate in Non-Modified Arteries: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines, 9(9), 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9091282