Combined Bacopa, Phosphatidylserine, and Choline Protect Against Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Treatments

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. In Vitro Model of Microglial Stress-Correlated Neuroinflammation

2.4. In Vitro Model of Microglial Stress-Correlated Neurotoxicity

2.5. In Vitro Iron-Dependent Oxidative Stress Model of Neurotoxicity

2.6. Cell Morphology Analysis

2.7. SRB Test

2.8. MTT Test

2.9. Western Blot Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Protection by Combined B. monnieri, Phosphatidylserine, and Choline (BPC) on CRH-Induced Microglia Activation

3.1.1. CRH Stimulation of BV2 Microglia Cells

3.1.2. Attenuation by BPC of CRH-Stimulated BV2 Cell Inflammatory Morphology

3.1.3. Role of Constituents on CRH-Stimulated BV2 Cell Morphology

3.1.4. Modulation of Stress-Related Markers

3.2. Protection by BPC from Neurotoxicity

3.2.1. Effect of BPC on CRH-Induced Neurotoxicity on SH-SY5Y Cells

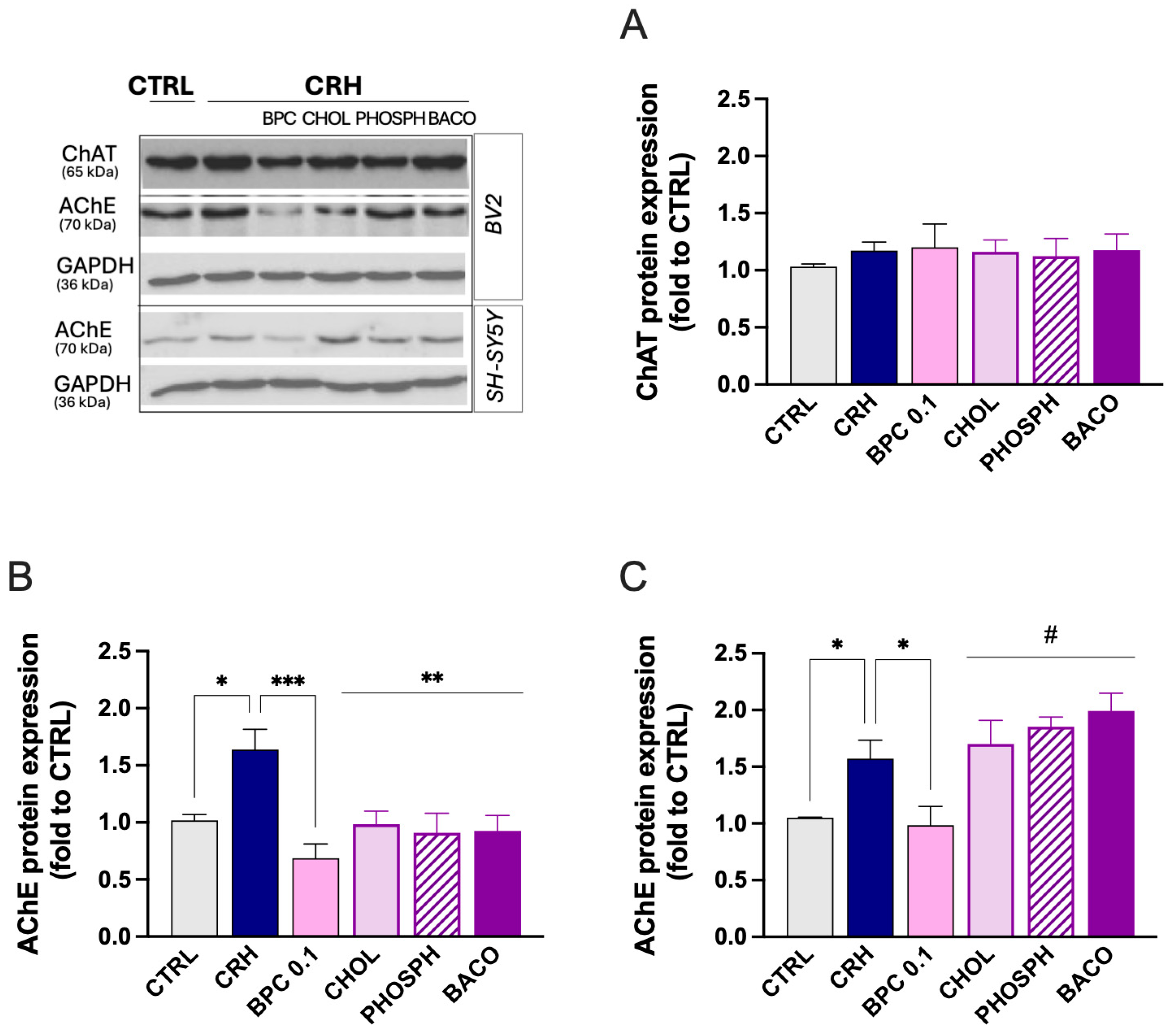

3.2.2. Effect of BPC on Cholinergic System

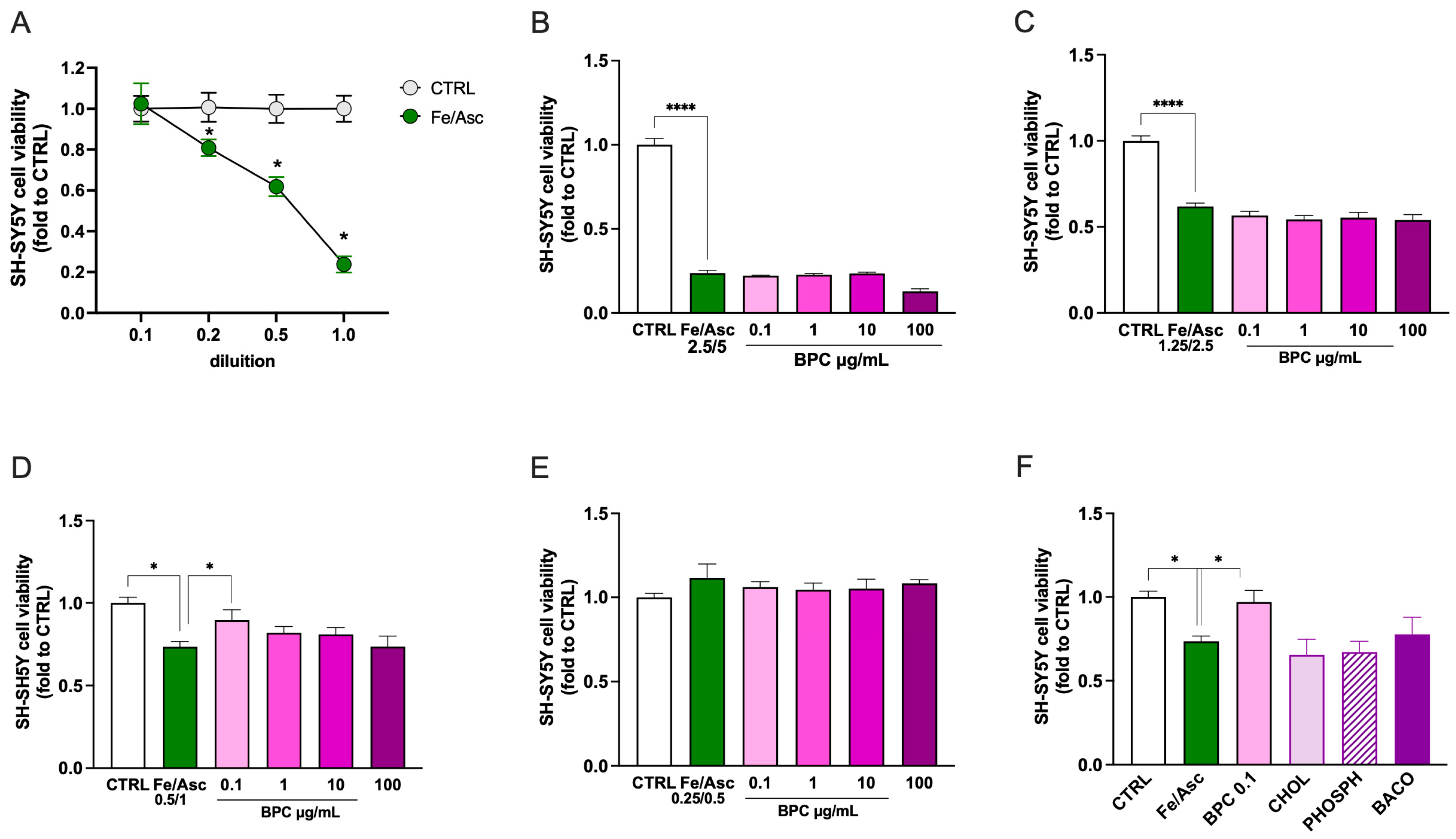

3.2.3. Effect of BPC on Neurotoxicity Induced by Fe/Asc Exposure

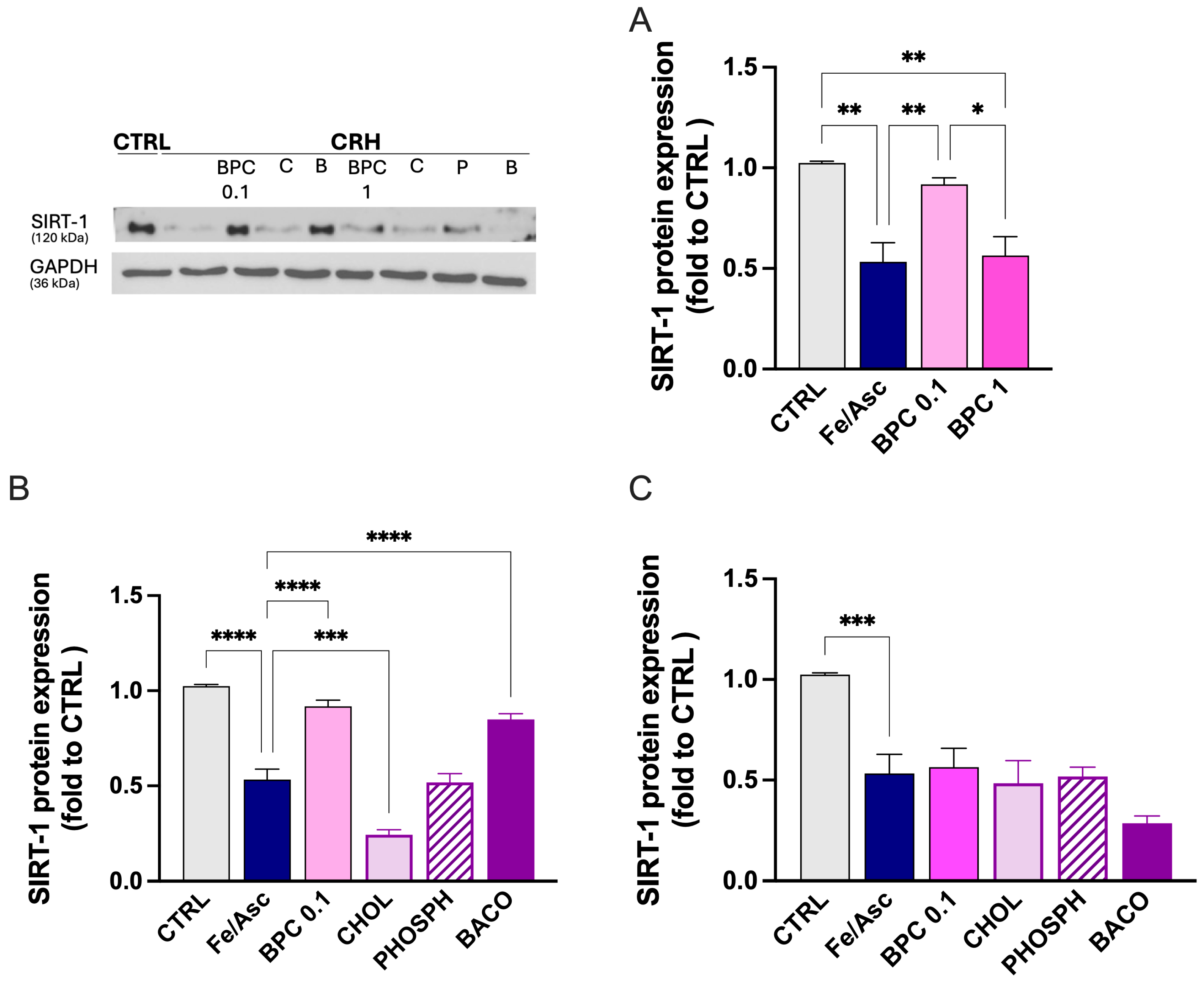

3.2.4. Restoration of SIRT-1 by BPC After Fe/Asc Exposure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ach | acetylcholine |

| AChE | acetylcholinesterase |

| BBB | blood brain barrier |

| BPC | Bacopa monnieri, phosphatidylserine, and choline |

| ChAT | choline acetyltransferase |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CRH | corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| HPA | hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| SNS | sympathetic nervous system |

| SRB | sulforhodamine B |

References

- Sapolsky, R.M. Stress and the Brain: Individual Variability and the Inverted-U. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1344–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Protective and Damaging Effects of Stress Mediators: Central Role of the Brain. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.Y.; Abdel Mageed, S.S.; Mansour, D.E.; Fawzi, S.F. The Cortisol Axis and Psychiatric Disorders: An Updated Review. Pharmacol. Rep. 2025, 77, 1573–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupien, S.J.; McEwen, B.S.; Gunnar, M.R.; Heim, C. Effects of Stress throughout the Lifespan on the Brain, Behaviour and Cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress and Hippocampal Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1999, 22, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupien, S.J.; Juster, R.P.; Raymond, C.; Marin, M.F. The Effects of Chronic Stress on the Human Brain: From Neurotoxicity, to Vulnerability, to Opportunity. Front. Neuroendocr. 2018, 49, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, J.L.; Roozendaal, B. Role of Adrenal Stress Hormones in Forming Lasting Memories in the Brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002, 12, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Irwin, M.R. From Stress to Inflammation and Major Depressive Disorder: A Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 774–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenrostro-Jáuregui, M.H.; Muñóz-Sánchez, S.; Rojas-Hernández, J.; Alonso-Orozco, A.I.; Vega-Flores, G.; Tapia-de-Jesús, A.; Leal-Galicia, P. A Comprehensive Overview of Stress, Resilience, and Neuroplasticity Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paribello, P.; Branchi, I.; Viglione, A.; Mancini, G.F.; Morena, M.; Campolongo, P.; Manchia, M. Biomarkers of Stress Resilience: A Review. Neurosci. Appl. 2024, 3, 104052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, V.; Ivanov, K.; Delattre, C.; Nalbantova, V.; Karcheva-Bahchevanska, D.; Ivanova, S. Plant Adaptogens-History and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel-Biedrawa, D.; Podolak, I. Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects of Adaptogens: A Mini-Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, T.; Chinnathambi, S. Brahmi (Bacopa monnieri): An Ayurvedic Herb against the Alzheimer’s Disease. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 676, 108153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemetchek, M.D.; Stierle, A.A.; Stierle, D.B.; Lurie, D.I. The Ayurvedic Plant Bacopa monnieri Inhibits Inflammatory Pathways in the Brain. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 197, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghav, S.; Singh, H.; Dalal, P.; Srivastava, J.; Asthana, O. Randomized Controlled Trial of Standardized Bacopa monniera Extract in Age-Associated Memory Impairment. Indian J. Psychiatry 2006, 48, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfan, M.; Kordestani-Moghaddam, P.; Gholami, M.; Kazemi, K.; Mohammadi, R. Evaluating the Effects of Bacopa monnieri on Cognitive Performance and Sleep Quality of Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Triple-Blinded, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Explore 2024, 20, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhaiya, H.C.; Desai, R.P.; Saxena, V.S.; Pravina, K.; Wasim, P.; Geetharani, P.; Allan, J.J.; Venkateshwarlu, K.; Amit, A. Efficacy and Tolerability of BacoMind® on Memory Improvement in Elderly Participants—A Double Blind Placebo Controlled Study. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008, 3, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopresti, A.L.; Smith, S.J. The Effects of a Bacopa monnieri Extract (Bacumen®) on Cognition, Stress, and Fatigue in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Drug Investig. 2025, 45, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Khan, I.; Chaudhary, M.N.; Ali, K.; Mushtaq, A.; Jiang, B.; Zheng, L.; Pan, Y.; Hu, J.; Zou, X. Phosphatidylserine: A Comprehensive Overview of Synthesis, Metabolism, and Nutrition. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2024, 264., 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersant, H.; He, S.; Maliha, P.; Grossberg, G. Over the Counter Supplements for Memory: A Review of Available Evidence. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansakar, U.; Trimarco, V.; Mone, P.; Varzideh, F.; Lombardi, A.; Santulli, G. Choline Supplements: An Update. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1148166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravina, K.; Ravindra, K.R.; Goudar, K.S.; Vinod, D.R.; Joshua, A.J.; Wasim, P.; Venkateshwarlu, K.; Saxena, V.S.; Amit, A. Safety Evaluation of BacoMindTM in Healthy Volunteers: A Phase I Study. Phytomedicine 2007, 14, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hahm, E.; Kim, Y.; Kang, J.; Lee, W.; Han, I.; Myung, P.; Kang, H.; Park, H.; Cho, D. Regulation of IL-18 Expression by CRH in Mouse Microglial Cells. Immunol. Lett. 2005, 98, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnaini, C.; Brizzi, A.; Paolino, M.; Scarselli, E.; Castelli, R.; de Candia, M.; Gambacorta, N.; Nicolotti, O.; Kostrzewa, M.; Kumar, P.; et al. Novel Dual-Acting Hybrids Targeting Type-2 Cannabinoid Receptors and Cholinesterase Activity Show Neuroprotective Effects In Vitro and Amelioration of Cognitive Impairment In Vivo. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 955–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasia, C.; Borgonetti, V.; Mancini, C.; Lori, G.; Arbiser, J.L.; Taddei, M.L.; Galeotti, N. The Neolignan Honokiol and Its Synthetic Derivative Honokiol Hexafluoro Reduce Neuroinflammation and Cellular Senescence in Microglia Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videtta, G.; Sasia, C.; Galeotti, N. High Rosmarinic Acid Content Melissa officinalis L. Phytocomplex Modulates Microglia Neuroinflammation Induced by High Glucose. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolicelli, R.C.; Sierra, A.; Stevens, B.; Tremblay, M.E.; Aguzzi, A.; Ajami, B.; Amit, I.; Audinat, E.; Bechmann, I.; Bennett, M.; et al. Microglia States and Nomenclature: A Field at Its Crossroads. Neuron 2022, 110, 3458–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Reed, K.M.; Carter, A.; Cheng, Y.; Roodsari, S.K.; Martinez Pineda, D.; Wellman, L.L.; Sanford, L.D.; Guo, M.L. Sleep-Disturbance-Induced Microglial Activation Involves CRH-Mediated Galectin 3 and Autophagy Dysregulation. Cells 2022, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, P.; Mehan, S.; Khan, Z.; Maurya, P.K.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, A.; Tiwari, A.; Sharma, T.; Das Gupta, G.; Narula, A.S.; et al. The SIRT-1/Nrf2/HO-1 Axis: Guardians of Neuronal Health in Neurological Disorders. Behav. Brain Res. 2025, 476, 115280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okorji, U.P.; Velagapudi, R.; El-Bakoush, A.; Fiebich, B.L.; Olajide, O.A. Antimalarial Drug Artemether Inhibits Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia Through Nrf2-Dependent Mechanisms. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6426–6443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Tang, T.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, L.; Lei, Z.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Z.; et al. Pterostilbene Attenuates Cocultured BV-2 Microglial Inflammation-Mediated SH-SY5Y Neuronal Oxidative Injury via SIRT-1 Signalling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 3986348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taupin, P. A Dual Activity of ROS and Oxidative Stress on Adult Neurogenesis and Alzheimer’s Disease. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempuraj, D.; Thangavel, R.; Natteru, P.A.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Saeed, D.; Zahoor, H.; Zaheer, S.; Iyer, S.S.; Zaheer, A. Neuroinflammation Induces Neurodegeneration. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Spine 2016, 1, 1003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fatima, U.; Roy, S.; Ahmad, S.; Al-Keridis, L.A.; Alshammari, N.; Adnan, M.; Islam, A.; Hassan, M.I. Investigating Neuroprotective Roles of Bacopa monnieri Extracts: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, R.; Li, D.; Xiang, X. Choline Intake and Cognitive Function Among U.S. Older Adults. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 42, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, H.; de Brugada, I. Prenatal Dietary Choline Supplementation Modulates Long-Term Memory Development in Rat Offspring. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glade, M.J.; Smith, K. Phosphatidylserine and the Human Brain. Nutrition 2015, 31, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, E.; Neves, B.M.; Martins, J.; Colombo, S.; Cruz, M.T.; Domingues, P.; Domingues, M.R.M. Oxidized Phosphatidylserine Mitigates LPS-Triggered Macrophage Inflammatory Status through Modulation of JNK and NF-KB Signaling Cascades. Cell. Signal. 2019, 61, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, M.; Costantini, E. Cholinergic Modulation of the Immune System in Neuroinflammatory Diseases. Diseases 2021, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Kumar, V.; Mukherjee, H.; Saini, S.; Gupta, S.; Chauhan, S.; Kushwaha, K.; Lahiri, D.; Sircar, D.; Roy, P. Assessment of the Mechanistic Role of an Indian Traditionally Used Ayurvedic Herb Bacopa monnieri (L.) Wettst. for Ameliorating Oxidative Stress in Neuronal Cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 328, 117899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, T.; Pase, M.; Stough, C. Bacopa monnieri as an Antioxidant Therapy to Reduce Oxidative Stress in the Aging Brain. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, 615384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baris, E.; Simsek, O.; Arici, M.A.; Tosun, M. Choline and Citicoline Ameliorate Oxidative Stress in Acute Kidney Injury in Rats. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2023, 124, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Kuang, M.; Wang, G.; Ali, I.; Tang, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Li, L. Choline Attenuates Heat Stress-Induced Oxidative Injury and Apoptosis in Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells by Modulating PERK/Nrf-2 Signaling Pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 135, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: Molecular Mechanisms and Health Implications. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent Form of Nonapoptotic Cell Death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Li, Y.; Deng, H.; Zuo, H. Advances in the Study of Cholinergic Circuits in the Central Nervous System. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2023, 10, 2179–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders: The Roles of Microglia and Astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Wu, Q.; Mak, S.; Liu, E.Y.L.; Zheng, B.Z.Y.; Dong, T.T.X.; Pi, R.; Tsim, K.W.K. Regulation of Acetylcholinesterase during the Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Responses in Microglial Cells. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, S.; Zia, M.A.; Uzair, M.; Attia, K.A.; Abushady, A.M.; Fiaz, S.; Ali, S.; Yang, S.H.; Ali, G.M. Bacopa monnieri: A Promising Herbal Approach for Neurodegenerative Disease Treatment Supported by in Silico and in Vitro Research. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sasia, C.; Videtta, G.; Galeotti, N. Combined Bacopa, Phosphatidylserine, and Choline Protect Against Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020340

Sasia C, Videtta G, Galeotti N. Combined Bacopa, Phosphatidylserine, and Choline Protect Against Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(2):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020340

Chicago/Turabian StyleSasia, Chiara, Giacomina Videtta, and Nicoletta Galeotti. 2026. "Combined Bacopa, Phosphatidylserine, and Choline Protect Against Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity" Biomedicines 14, no. 2: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020340

APA StyleSasia, C., Videtta, G., & Galeotti, N. (2026). Combined Bacopa, Phosphatidylserine, and Choline Protect Against Stress-Induced Neurotoxicity. Biomedicines, 14(2), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020340