Potential Applications of Additive Manufacturing in Intervertebral Disc Replacement Using Gyroid Structures with Several Thermoplastic Polyurethane Filaments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Filament Preparation

2.2.2. Three-Dimensional Printing Parameter Optimization

2.2.3. Additive Manufacturing

2.3. Sample Characterization

2.3.1. Microscopy

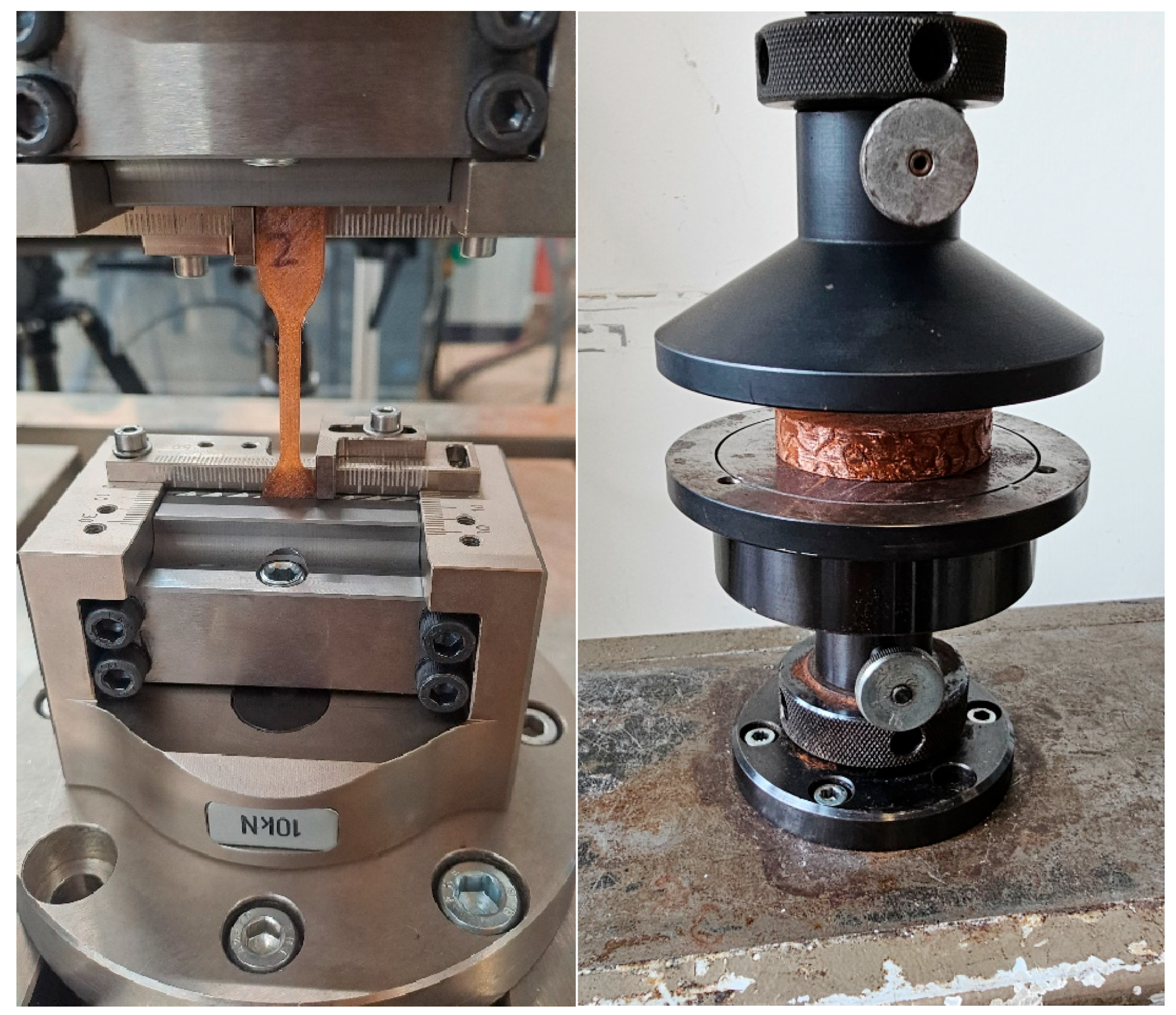

2.3.2. Mechanical Properties

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Sample Dimensions

3.2. Mechanical Properties

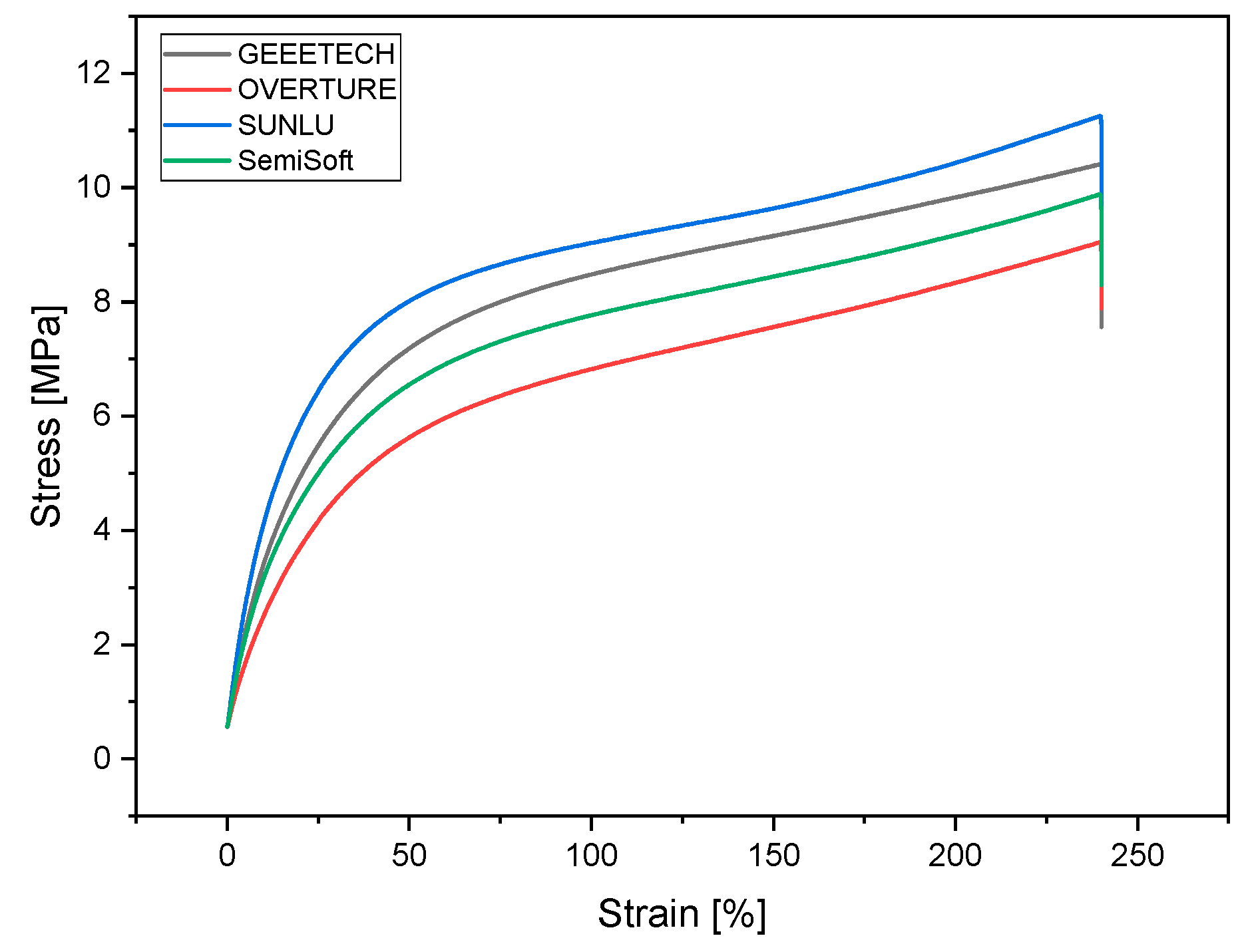

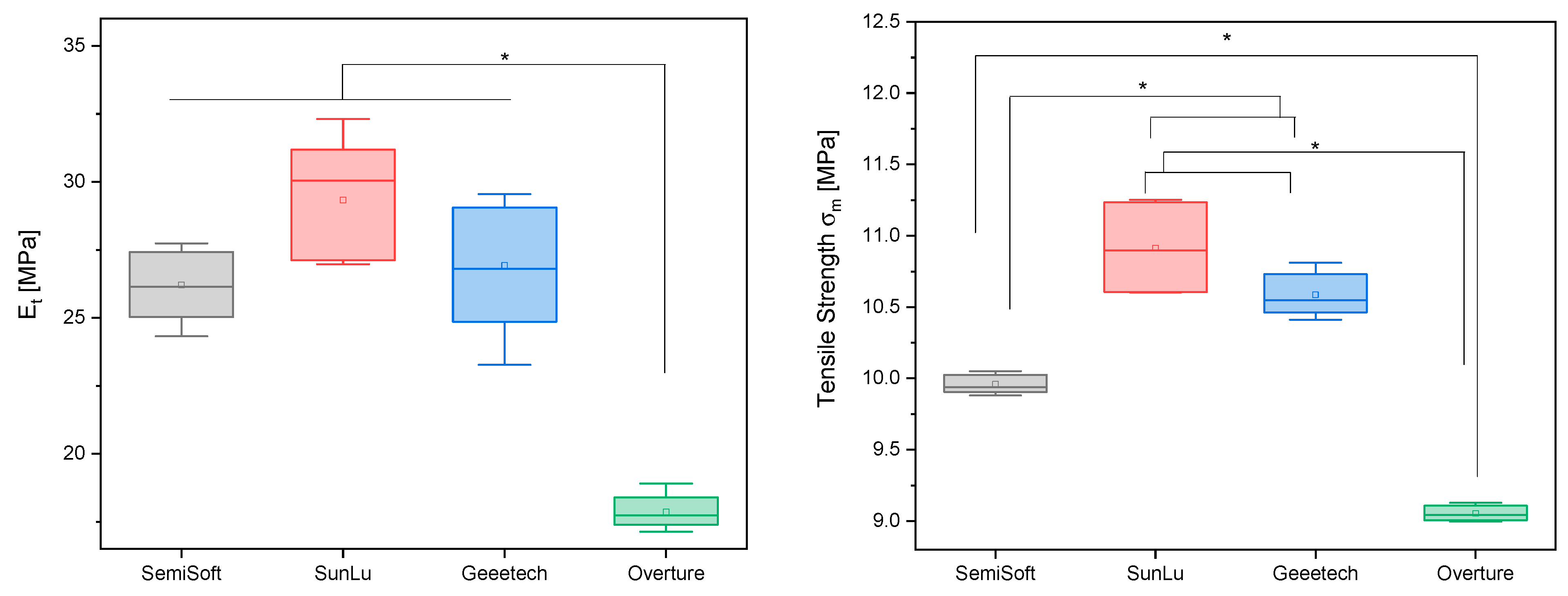

3.2.1. Tensile Tests

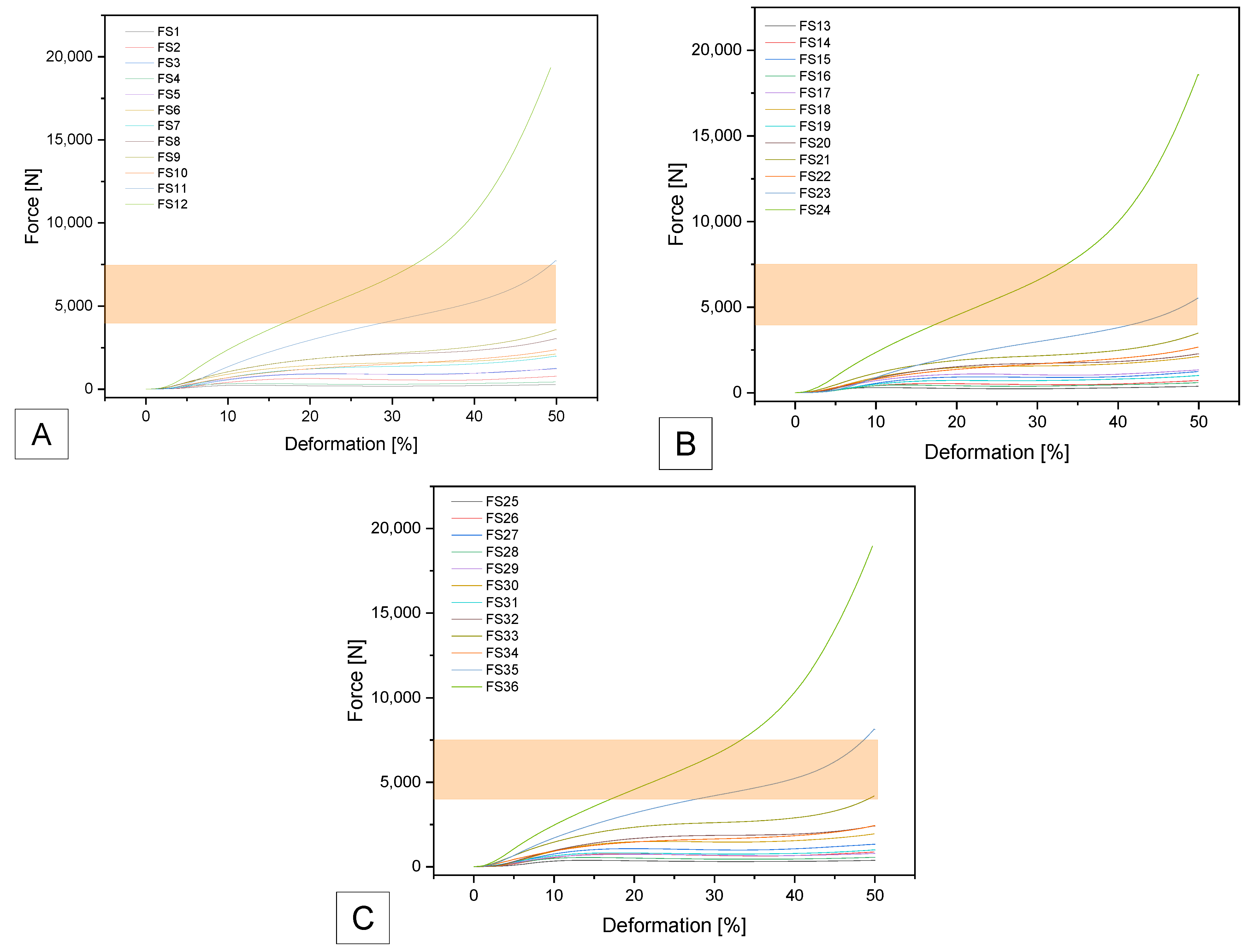

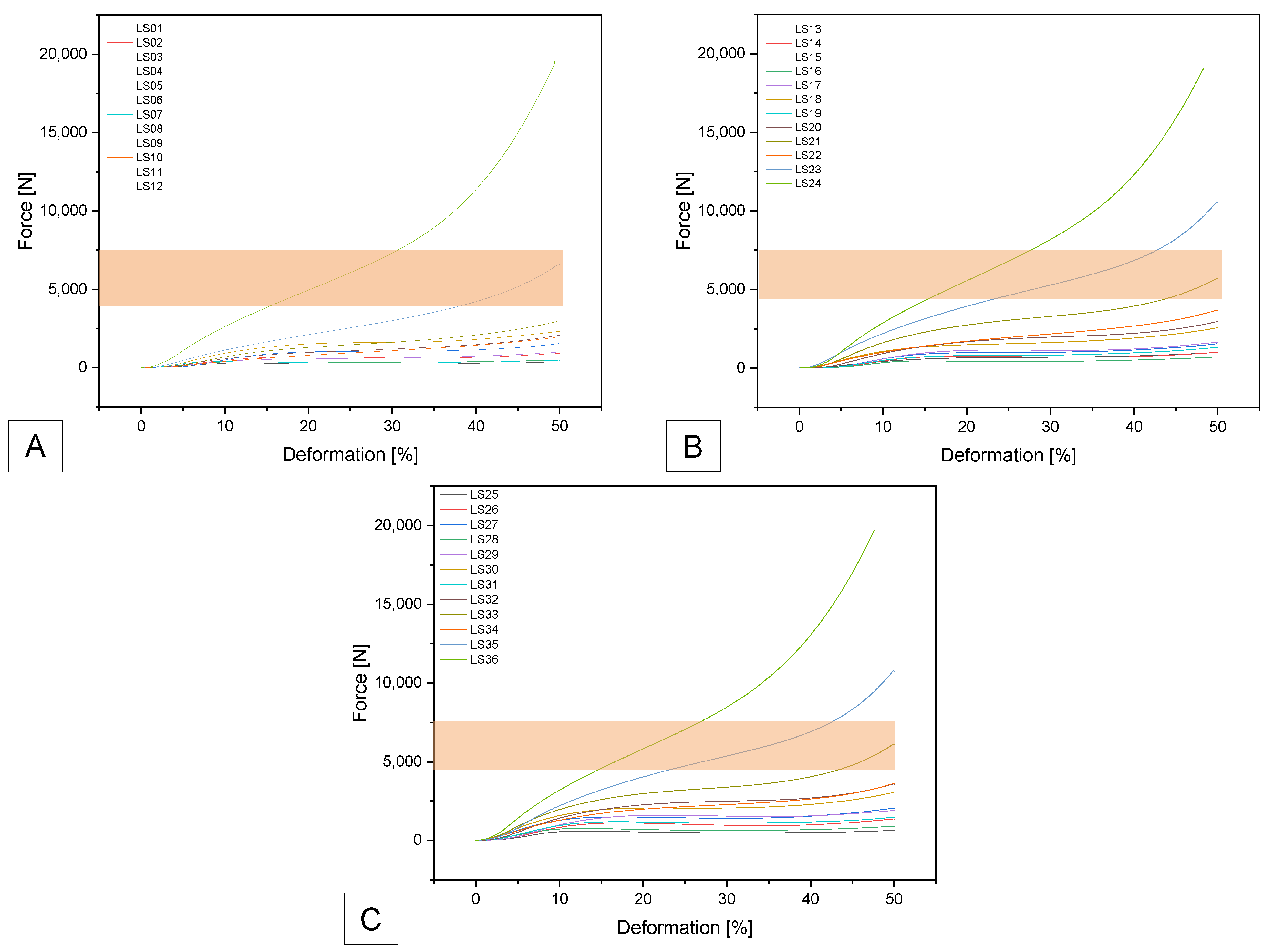

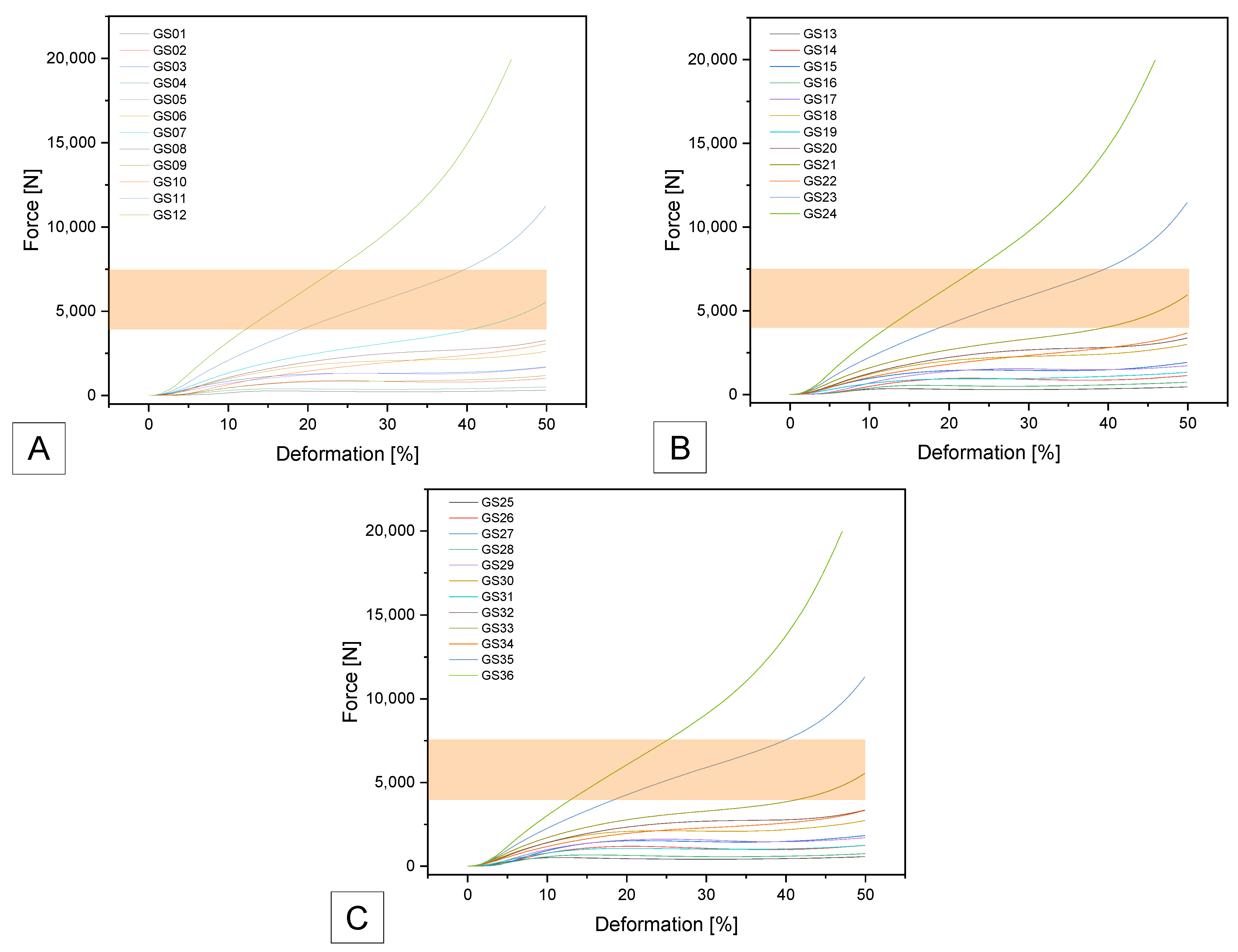

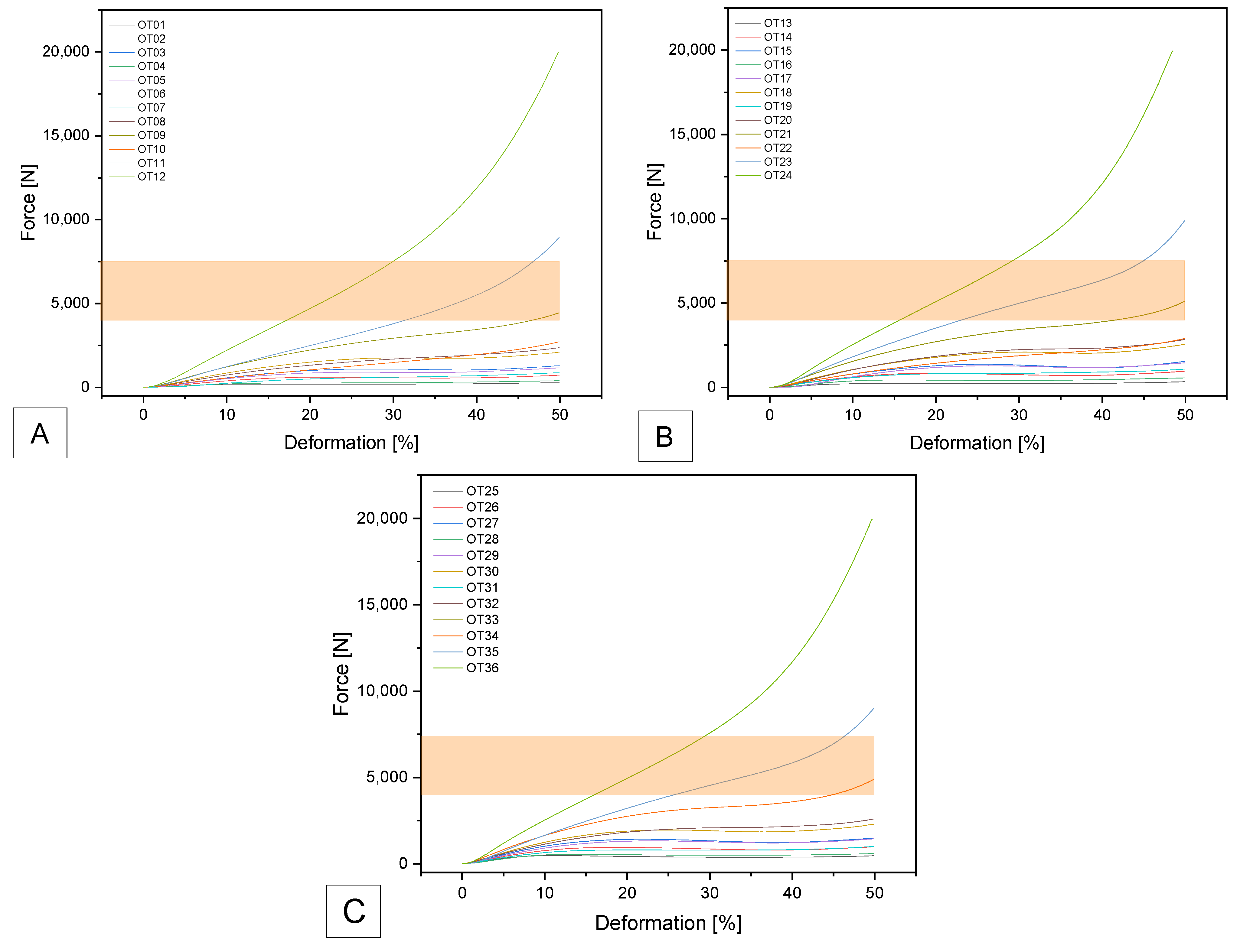

3.2.2. Compression Tests

SemiSoft

SUNLU

GEEETECH

OVERTURE

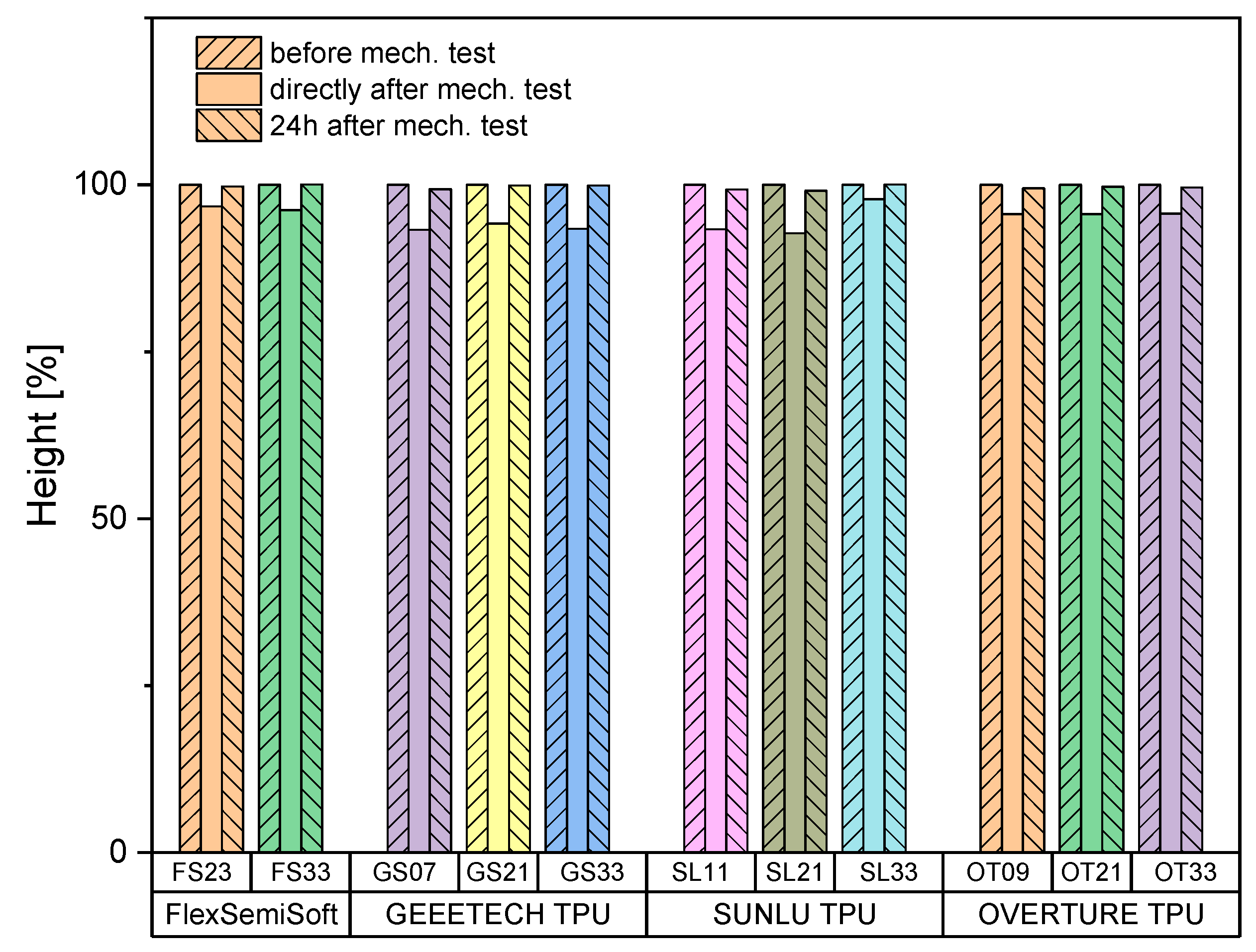

3.2.3. Sample Height

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASD | adjacent segment degeneration |

| CAD | computer-aided design |

| FDM | fused deposition modelling |

| FS | Flex Semisoft Filament Sample |

| G-code | geometry code |

| GS | Geeetech TPU Filament Sample |

| OT | Overture TPU Filament Sample |

| ROM | range of motion |

| SL | Sunlu TPU Filament Sample |

| STL | stereo lithography file |

| TPU | thermoplastic polyurethane |

| Not listed here are SI abbreviations. | |

Appendix A

| Sample | Gyroid Dimensions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume [mm3] | Wall Thickness Gyroid [mm] | Wall Thickness Outer Wall [mm] | |

| #01 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| #02 | 10 | 0.75 | 0.4 |

| #03 | 10 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| #04 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| #05 | 8 | 0.75 | 0.4 |

| #06 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| #07 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| #08 | 6 | 0.75 | 0.4 |

| #09 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| #10 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| #11 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.4 |

| #12 | 4 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| #13 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| #14 | 10 | 0.75 | 0.6 |

| #15 | 10 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| #16 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| #17 | 8 | 0.75 | 0.6 |

| #18 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| #19 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| #20 | 6 | 0.75 | 0.6 |

| #21 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| #22 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

| #23 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.6 |

| #24 | 4 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| #25 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| #26 | 10 | 0.75 | 0.8 |

| #27 | 10 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| #28 | 8 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| #29 | 8 | 0.75 | 0.8 |

| #30 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| #31 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| #32 | 6 | 0.75 | 0.8 |

| #33 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| #34 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| #35 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.8 |

| #36 | 4 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Specimen | Gyroid Wall (Target) [mm] | Gyroid Wall (Measured) [mm] | Δ Gyroid Wall [%] | Outer Wall (Target) [mm] | Outer Wall (Measured) [mm] | Δ Outer Wall [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FlexSemiSoft | ||||||

| FS01 | 0.5 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 2.0 ± 0.06 | 0.4 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.0 ± 0.05 |

| FS02 | 0.75 | 0.70 ± 0.02 * | 6.7 ± 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.03 |

| FS03 | 1.0 | 0.90 ± 0.03 * | 10.0 ± 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.42 ± 0.07 | 5.0 ± 0.18 |

| FS13 | 0.5 | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 14.0 ± 0.18 | 0.6 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 1.7 ± 0.03 |

| FS14 | 0.75 | 0.70 ± 0.07 * | 6.7 ± 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 5.0 ± 0.03 * |

| FS15 | 1.0 | 0.99 ± 0.11 | 1.0 ± 0.11 | 0.6 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 3.3 ± 0.07 * |

| FS25 | 0.5 | 0.43 ± 0.04 * | 14.0 ± 0.08 | 0.8 | 0.75 ± 0.05 * | 6.3 ± 0.06 * |

| FS26 | 0.75 | 0.72 ± 0.08 * | 4.0 ± 0.11 | 0.8 | 0.77 ± 0.01 * | 3.8 ± 0.01 * |

| FS27 | 1.0 | 0.93 ± 0.05 * | 7.0 ± 0.05 | 0.8 | 0.74 ± 0.07 * | 7.5 ± 0.09 * |

| SUNLU | ||||||

| SL01 | 0.5 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | 2.0 ± 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.0 ± 0.05 |

| SL02 | 0.75 | 0.70 ± 0.01 * | 6.7 ± 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.0 ± 0.03 |

| SL03 | 1 | 0.92 ± 0.01 * | 8.0 ± 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 10.0 ± 0.18 |

| SL13 | 0.5 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 2.0 ± 0.08 | 0.6 | 0.62 ± 0.02 | 3.3 ± 0.03 |

| SL14 | 0.75 | 0.72 ± 0.06 * | 4.0 ± 0.06 | 0.6 | 0.63 ± 0.02 * | 5.0 ± 0.08 |

| SL15 | 1 | 0.99 ± 0.10 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 6.7 ± 0.06 |

| SL25 | 0.5 | 0.45 ± 0.01 * | 10.0 ± 0.01 | 0.8 | 0.78 ± 0.05 * | 2.5 ± 0.02 |

| SL26 | 0.75 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 1.3 ± 0.06 | 0.8 | 0.75 ± 0.07 * | 6.3 ± 0.09 |

| SL27 | 1.0 | 0.91 ± 0.05 * | 9.0 ± 0.05 | 0.8 | 0.74 ± 0.01 * | 7.5 ± 0.01 |

| GEETECH | ||||||

| GS01 | 0.5 | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 2.0 ± 0.02 | 0.4 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 2.5 ± 0.08 |

| GS02 | 0.75 | 0.77 ± 0.01 * | 2.7 ± 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 5.0 ± 0.05 * |

| GS03 | 1 | 1.02 ± 0.06 | 2.0 ± 0.06 | 0.4 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 2.5 ± 0.03 |

| GS13 | 0.5 | 0.48 ± 0.02 * | 4.0 ± 0.04 | 0.6 | 0.57 ± 0.02 | 5.0 ± 0.08 |

| GS14 | 0.75 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.0 ± 0.01 | 0.6 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 3.3 ± 0.03 |

| GS15 | 1 | 0.99 ± 0.05 | 1.0 ± 0.05 | 0.6 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 8.3 ± 0.03 * |

| GS25 | 0.5 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.0 ± 0.06 | 0.8 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.03 |

| GS26 | 0.75 | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 0.0 ± 0.03 | 0.8 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.05 * |

| GS27 | 1 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 4.0 ± 0.04 | 0.8 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 1.3 ± 0.05 |

| OVERTURE | ||||||

| OT01 | 0.5 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 2.0 ± 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 0.0 ± 0.05 |

| OT02 | 0.75 | 0.76 ± 0.01 | 1.3 ± 0.01 | 0.4 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 2.5 ± 0.05 |

| OT03 | 1 | 0.99 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.0 ± 0.08 |

| OT13 | 0.5 | 0.49 ± 0.05 | 2.0 ± 0.10 | 0.6 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 1.7 ± 0.03 |

| OT14 | 0.75 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 1.3 ± 0.04 | 0.6 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.0 ± 0.02 |

| OT15 | 1 | 1.01 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.04 | 0.6 | 0.60 ± 0.01 | 0.0 ± 0.02 |

| OT25 | 0.5 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 2.0 ± 0.02 | 0.8 | 0.81 ± 0.01 * | 1.3 ± 0.01 |

| OT26 | 0.75 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.0 ± 0.01 | 0.8 | 0.81 ± 0.02 | 1.3 ± 0.03 |

| OT27 | 1 | 0.98 ± 0.03 | 2.0 ± 0.03 | 0.8 | 0.82 ± 0.02 * | 2.5 ± 0.03 |

| Sample | Gyroid Size [mm] | Gyroid Wall [mm] | Outer Wall [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extrudr FlexSemiSoft | |||

| FS23 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.6 |

| FS33 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| SUNLU TPU | |||

| SL11 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.4 |

| SL21 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| SL33 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| GEEETECH TPU | |||

| GS07 | 6 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| GS21 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| GS33 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| OVERTURE TPU | |||

| OT09 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.4 |

| OT21 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| OT33 | 6 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

References

- Abudouaini, H.; Wu, T.; Meng, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, H. Mechanical properties of an elastically deformable cervical spine implant. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedmakers, C.M.W.; de Vries, F.; Bosscher, L.; Peul, W.C.; Arts, M.P.; Vleggeert-Lankamp, C.L.A. Long-term results of the NECK trial—Implanting a disc prosthesis after cervical anterior discectomy cannot prevent adjacent segment disease: Five-year clinical follow-up of a double-blinded randomised controlled trial. Spine J. 2023, 23, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Hanna, D.; Kerferd, J.; Phan, K.; Rao, P.; Mobbs, R. Lumbar Disk Arthroplasty for Degenerative Disk Disease: Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2018, 109, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; OuYang, P.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Sun, Z.; Dong, H.; Wen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gu, P.; Lu, T.; et al. Cervical non-fusion using biomimetic artificial disc and vertebra complex: Technical innovation and biomechanics analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2022, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.-D.; Li, H.-T.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L.-L.; Luo, Z.-P.; Yang, H.-L. Mid- to long-term results of total disc replacement for lumbar degenerative disc disease: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2018, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Cai, Y.; Chen, K.; Ren, Q.; Huang, B.; Wan, G.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhao, J. Risk factors and treatment strategies for adjacent segment disease following spinal fusion (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 31, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, U.K.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, M.C.; Willenberg, R.; Kim, S.H.; Lim, J. Range of motion change after cervical arthroplasty with ProDisc-C and prestige artificial discs compared with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2007, 7, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Wang, H.; Peng, J.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, D.; Gong, M.; Tang, S. Rate of Adjacent Segment Degeneration of Cervical Disc Arthroplasty Versus Fusion Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. World Neurosurg. 2018, 113, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destatis. Fallpauschalenbezogene Krankenhausstatistik (DRG-Statistik) Operationen und Prozeduren der Vollstationären Patientinnen und Patienten in Krankenhäusern (4-Steller) für 2021; Federal Statistical Office of Germany: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022.

- Cloyd, J.M.; Malhotra, N.R.; Weng, L.; Chen, W.; Mauck, R.L.; Elliott, D.M. Material properties in unconfined compression of human nucleus pulposus, injectable hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels and tissue engineering scaffolds. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, A.; Girdler, S.J.; Mikhail, C.M.; Ahn, A.; Cho, S.K. Biomaterials in Spinal Implants: A Review. Neurospine 2020, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, T.; Capelli, C.; Toumpaniari, R.; Orriss, I.R.; Leong, J.J.H.; Dalgarno, K.; Kalaskar, D.M. Design and fabrication of 3D-printed anatomically shaped lumbar cage for intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration treatment. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.L.; Jacobsen, T.D.; Emsbo, E.; Murali, A.; Anton, K.; Liu, J.Z.; Lu, H.H.; Chahine, N.O. Three-Dimensional-Printed Flexible Scaffolds Have Tunable Biomimetic Mechanical Properties for Intervertebral Disc Tissue Engineering. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 5836–5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidai, A.B.; Kim, B.; Lintz, M.; Kirnaz, S.; Gadjradj, P.; Boadi, B.I.; Koga, M.; Hussain, I.; Härtl, R.; Bonassar, L.J. Flexible support material maintains disc height and supports the formation of hydrated tissue engineered intervertebral discs in vivo. JOR Spine 2024, 7, e1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, M.N.; Berto, N.A.; Radhi, S.H. Preparation and characterization of UHMWPE reinforced with polyester fibers for artificial cervical disc replacement (ACDR). J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2023, 34, 1758–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Gao, Y. The manufacture of 3D printing of medical grade TPU. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 2, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, V.; Zankovic, S.; Rolauffs, B.; Velten, D.; Schmal, H.; Seidenstuecker, M. On the suitability of additively manufactured gyroid structures and their potential use as intervertebral disk replacement—a feasibility study. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1432587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.H.; Campbell, G. Formulations of polyvinyl alcohol cryogel that mimic the biomechanical properties of soft tissues in the natural lumbar intervertebral disc. Spine 2009, 34, 2745–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohlmann, A.; Wilke, H.-J.; Mellerowicz, H.; Graichen, F.; Bergmann, G. Loads on the spine in sports. Ger. J. Sports Med. 2001, 52, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, H.J.; Neef, P.; Caimi, M.; Hoogland, T.; Claes, L.E. New in vivo measurements of pressures in the intervertebral disc in daily life. Spine 1999, 24, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.J.; Jung, Y.S.; Choi, H.Y.; Lee, S. Synthesis and fabrication of biobased thermoplastic polyurethane filament for FDM 3D printing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e52959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryńska, A.; Gubanska, I.; Kucinska-Lipka, J.; Janik, H. Fabrication and Characterization of Flexible Medical-Grade TPU Filament for Fused Deposition Modeling 3DP Technology. Polymers 2018, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.J.; Park, Y.; Jung, Y.S.; Choi, H.Y.; Lee, S. Fabrication and characteristics of flexible thermoplastic polyurethane filament for fused deposition modeling three-dimensional printing. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2022, 62, 2947–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanmohammadi, K.; Rahmatabadi, D.; Aberoumand, M.; Soleyman, E.; Ghasemi, I.; Baniassadi, M.; Abrinia, K.; Bodaghi, M.; Baghani, M. Effects of TPU on the mechanical properties, fracture toughness, morphology, and thermal analysis of 3D-printed ABS-TPU blends by FDM. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2024, 30, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, A.; Ahmadi, M.; Rahmatabadi, D.; Khodaei, M.; Xiang, H.; Baniassadi, M.; Abrinia, K.; Zolfagharian, A.; Bodaghi, M.; Baghani, M. 3D printed elastomers with superior stretchability and mechanical integrity by parametric optimization of extrusion process using Taguchi Method. Mater. Res. Express 2025, 12, 015301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrlybayev, D.; Zharylkassyn, B.; Seisekulova, A.; Akhmetov, M.; Perveen, A.; Talamona, D. Optimisation of Strength Properties of FDM Printed Parts—A Critical Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.; MB, P.; Shet, N.K.; Ghosh, A.K.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Mukhopadhyay, P. Microstructure and mechanical performance examination of 3D printed acrylonitrile butadiene styrene thermoplastic parts. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 2770–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Kong, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Yin, Q.; Xing, D.; Li, P. A review on voids of 3D printed parts by fused filament fabrication. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 4860–4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feki, F.; Zaïri, F.; Tamoud, A.; Moulart, M.; Taktak, R.; Haddar, N.; Zaïri, F. Understanding the Recovery of the Intervertebral Disc: A Comprehensive Review of In Vivo and In Vitro Studies. J. Bionic Eng. 2024, 21, 1919–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, J.P.G.; Maroudas, A. Swelling of the Intervertebral Disc In Vitro. Connect. Tissue Res. 1981, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, J.P.; McMullin, J.F. Swelling pressure of the lumbar intervertebral discs: Influence of age, spinal level, composition, and degeneration. Spine 1988, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsford, D.J.; Esses, S.I.; Ogilvie-Harris, D.J. In vivo diurnal variation in intervertebral disc volume and morphology. Spine 1994, 19, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.A.; Dolan, P.; Hutton, W.C.; Porter, R.W. Diurnal changes in spinal mechanics and their clinical significance. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 1990, 72, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D.W.; Garbutt, G.; Adams, M.A. Effect of sustained loading on the water content of intervertebral discs: Implications for disc metabolism. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1996, 55, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malko, J.A.; Hutton, W.C.; Fajman, W.A. An in vivo MRI study of the changes in volume (and fluid content) of the lumbar intervertebral disc after overnight bed rest and during an 8-hour walking protocol. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 2002, 15, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.A.; Hutton, W.C. The effect of posture on the fluid content of lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine 1983, 8, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, M.A.; Dolan, P. Recent advances in lumbar spinal mechanics and their clinical significance. Clin. Biomech. 1995, 10, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Filament | Shore A | Density [g/cm3] | Tensile Strength [MPa] * | Elongation at Break [%] ** | Tg [°C] | Tm [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUNLU | 95 | 1.23 | 21.7 | 536 | −24 | 190–220 |

| OVERTURE | 95 | 1.18 | 30.1 | 332 | −23 | 210 |

| GEEETECH | 95 | 1.30 | 23.6 | 525 | −24 | 185–220 |

| SemiSoft | 85 | 1.18 | 42 | 550 | −24 | 180–230 |

| Temperature [°C] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SemiSoft | Sunlu | Geeetech | Overture | |

| IX | 255 | 210 | 240 | 230 |

| VIII | 252 | 207 | 235 | 227 |

| VII | 250 | 205 | 230 | 225 |

| VI | 247 | 202 | 225 | 222 |

| V | 245 | 200 | 220 | 220 |

| IV | 242 | 197 | 215 | 217 |

| III | 240 | 195 | 210 | 215 |

| II | 237 | 192 | 205 | 212 |

| I | 235 | 190 | 200 | 200 |

| SemiSoft | Et [MPa] | σX [MPa] | σm [MPa] | εm [%] |

| Mean | 26.2 | 3.2 | 10.0 | 240.6 |

| Min | 24.3 | 3.1 | 9.9 | 239.7 |

| Max | 27.7 | 3.2 | 10.1 | 241.3 |

| SD | 1.3 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| SUNLU | Et [MPa] | σX [MPa] | σm [MPa] | εm [%] |

| Mean | 29.3 | 3.9 | 10.9 | 240.0 |

| Min | 27.0 | 3.6 | 10.0 | 239.6 |

| Max | 32.3 | 4.1 | 11.3 | 240.8 |

| SD | 2.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| GEEETECH | Et [MPa] | σX [MPa] | σm [MPa] | εm [%] |

| Mean | 26.9 | 3.5 | 10.6 | 240.7 |

| Min | 23.3 | 3.4 | 10.4 | 239.8 |

| Max | 29.6 | 3.6 | 10.8 | 241.6 |

| SD | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.7 |

| OVERTURE | Et [MPa] | σX [MPa] | σm [MPa] | εm [%] |

| Mean | 17.9 | 2.5 | 9.1 | 239 |

| Min | 17.1 | 2.4 | 9.0 | 237.5 |

| Max | 18.9 | 2.5 | 9.1 | 239.9 |

| SD | 0.6 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.9 |

| Extrudr FlexSemiSoft | ||||||||

| 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | 0.8 mm | ||||||

| Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] |

| - | - | - | FS23 | 6918 ± 66 | 3.52 ± 0.03 | FS33 | 4171 ± 38 | 2.13 ± 0.02 |

| SUNLU TPU | ||||||||

| 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | 0.8 mm | ||||||

| Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] |

| SL11 | 6607 ± 267 | 3.4 ± 0.16 | SL21 | 5718 ± 222 | 2.9 ± 0.11 | SL33 | 6123 ± 207 | 3.1 ± 0.08 |

| GEEETECH TPU | ||||||||

| 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | 0.8 mm | ||||||

| Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] |

| GS07 | 5533 ± 38 | 2.81 ± 0.06 | GS21 | 5935 ± 221 | 3.02 ± 0.09 | GS33 | 5542 ± 190 | 2.82 ± 0.08 |

| OVERTURE TPU | ||||||||

| 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | 0.8 mm | ||||||

| Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] | Sample | Fmax [N] | σD [MPa] |

| OT09 | 4585 ± 117 | 2.29 ± 0.06 | OT21 | 5171 ± 45 | 2.55 ± 0.02 | OT33 | 4922 ± 69 | 2.38 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hippel, L.; Mussler, J.; Velten, D.; Rolauffs, B.; Schmal, H.; Seidenstuecker, M. Potential Applications of Additive Manufacturing in Intervertebral Disc Replacement Using Gyroid Structures with Several Thermoplastic Polyurethane Filaments. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020323

Hippel L, Mussler J, Velten D, Rolauffs B, Schmal H, Seidenstuecker M. Potential Applications of Additive Manufacturing in Intervertebral Disc Replacement Using Gyroid Structures with Several Thermoplastic Polyurethane Filaments. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(2):323. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020323

Chicago/Turabian StyleHippel, Leandro, Jan Mussler, Dirk Velten, Bernd Rolauffs, Hagen Schmal, and Michael Seidenstuecker. 2026. "Potential Applications of Additive Manufacturing in Intervertebral Disc Replacement Using Gyroid Structures with Several Thermoplastic Polyurethane Filaments" Biomedicines 14, no. 2: 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020323

APA StyleHippel, L., Mussler, J., Velten, D., Rolauffs, B., Schmal, H., & Seidenstuecker, M. (2026). Potential Applications of Additive Manufacturing in Intervertebral Disc Replacement Using Gyroid Structures with Several Thermoplastic Polyurethane Filaments. Biomedicines, 14(2), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020323