An Update on the Correlation Between Neuroimmunomodulation, Photodynamic Therapy (PDT), and Wound Healing: The Role of Mast Cells

Abstract

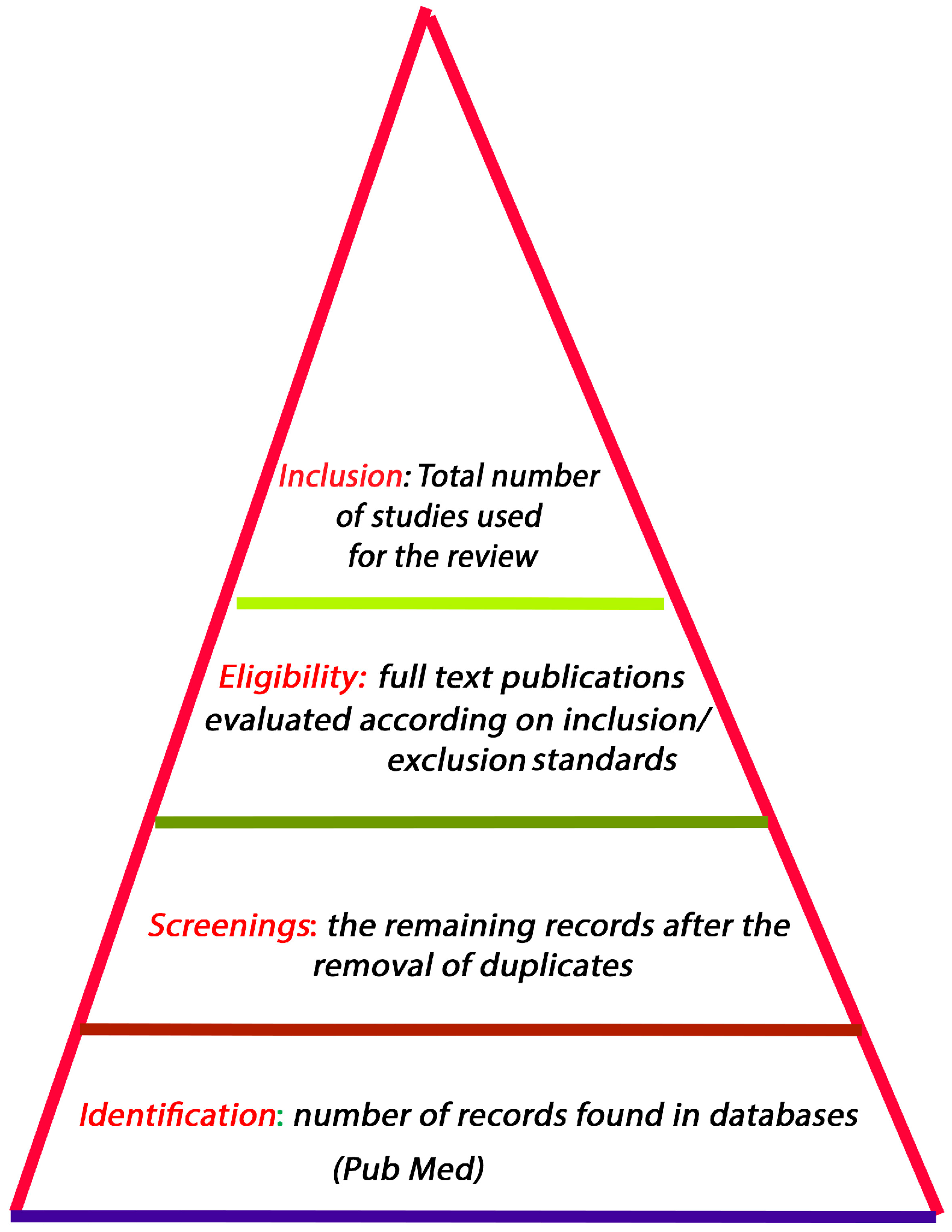

1. Approach

2. Introduction

3. Phases of Wound Healing

3.1. Hemostasis

3.2. Inflammation

3.3. Proliferation

3.4. Remodeling/Maturation

4. Molecular Biomarkers in Wound Healing

5. Genetic Activation in Wound Healing

6. Dysfunction of the Cellular Mechanisms Associated with Wound Healing

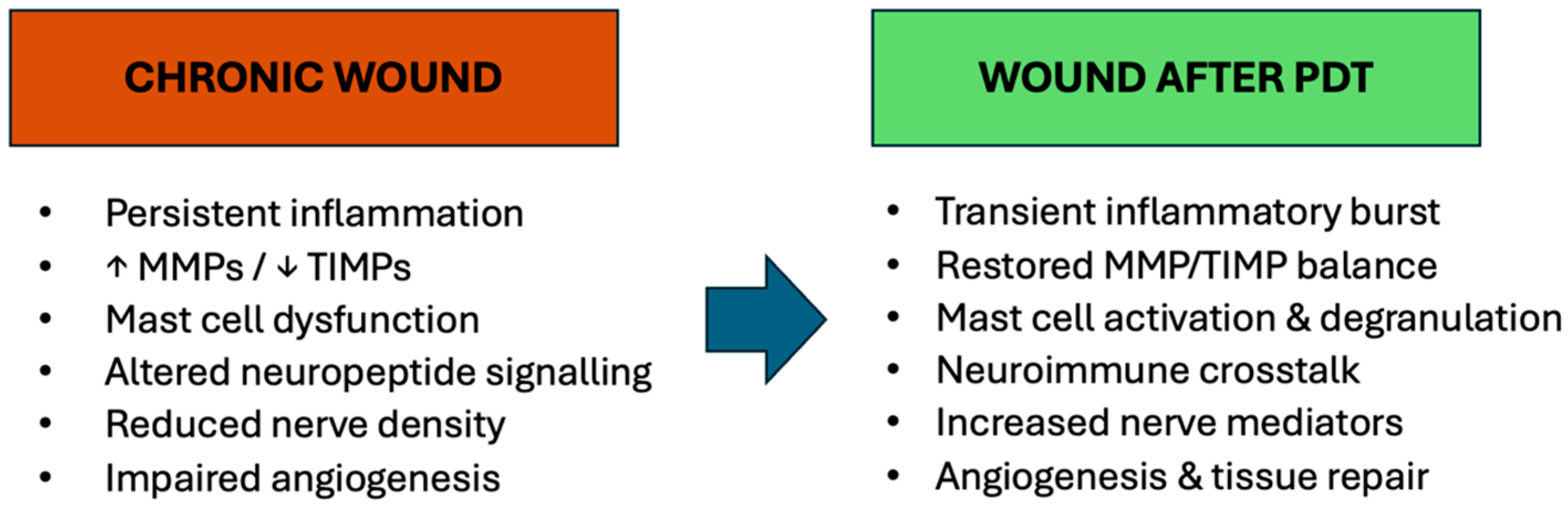

Chronic Wounds

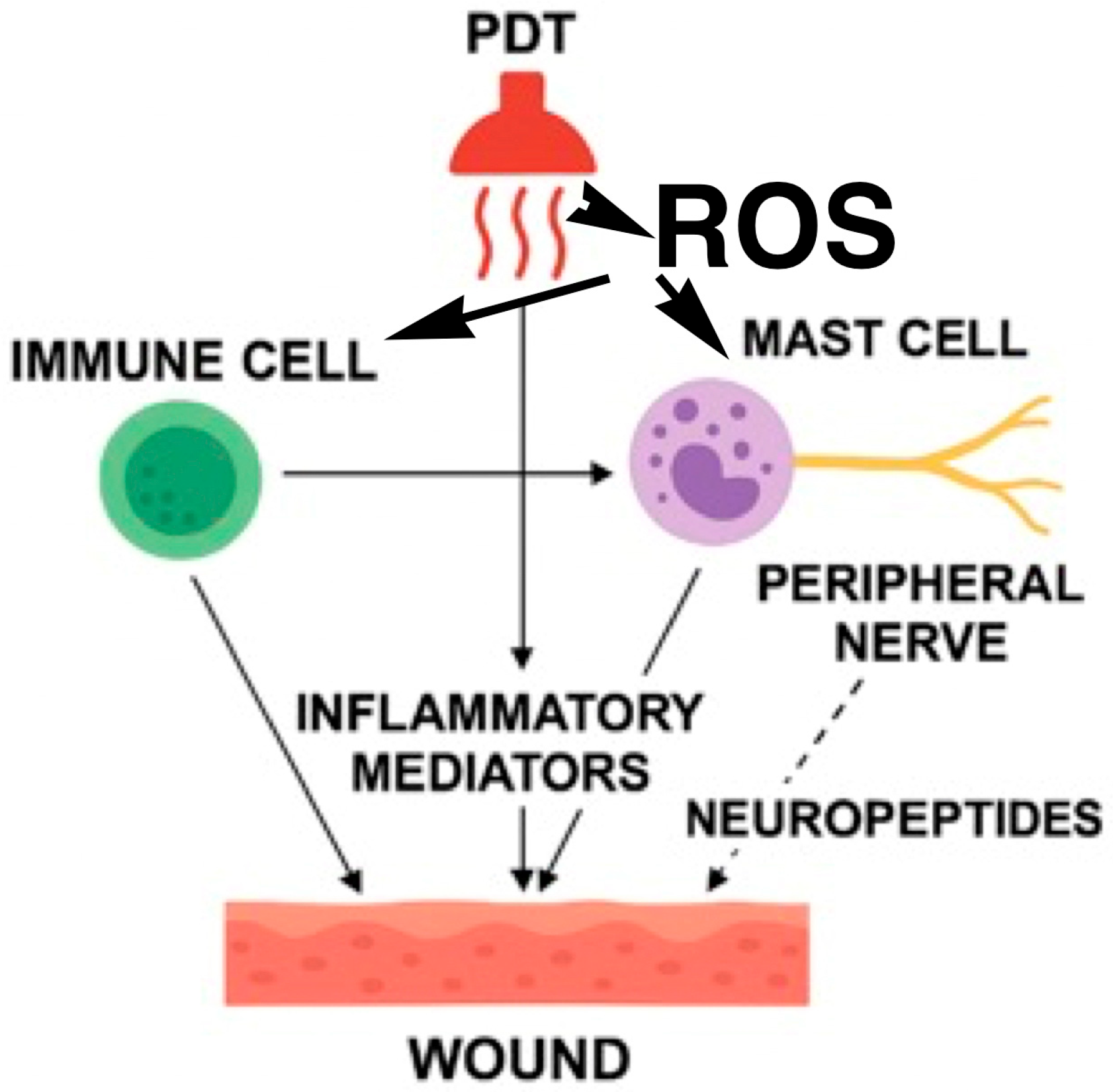

7. Neuroimmunomodulation During Wound Healing

7.1. Inflammatory Phase

7.2. Proliferative Phase

7.3. Remodeling Phase

7.4. Neuroimmunomodulation in Chronic Wounds

8. Photodynamic Therapy

8.1. Biomolecular Impact of PDT

8.2. Response of Cellular Infiltrate

8.3. Neuroimmunomodulatory Effects of PDT in Chronic Wounds

8.4. Clinical Evidence of PDT in Chronic Wounds

9. Conclusions and Prospective of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WH | Wound Healing |

| CW | Chronic Wounds |

| MC | Mast cells |

| SMA | Smooth Muscle Actin |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| TIMPs | Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| KGF | Keratinocyte Growth Factor |

| EGF | Epithelial Growth Factor |

| HGF | Hepatocyte Growth Factor |

| IGF | Insulin-like Growth Factor |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors |

| AP1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| ERG | ETS-related Gene |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| CaMK | Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| JNK | c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| TYR | Tyrosinases |

| TYRP1 | Tyrosinase-Related Protein 1 |

| DCT | Dopachrome Tautomerase |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| CCNB1 | Cyclin B1 |

| CHEK1 | Checkpoint Kinase 1 |

| CDK1 | Cyclin Dependent Kinase 1 |

| COL4A1 | Collagen Alpha Chain 1 |

| COL4A2 | Collagen Type 4 Alpha Chain 2 |

| COL6A1 | Collagen Type 6 Alpha Chain 1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| IFN | Interferon |

| MRLF | MRL/MpJ-Faslpr |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| ALA | Aminolevulinic Acid |

| SP | Substance P |

| NEP | Neutral endopeptidase |

| NK1R | Neurokinin-1 receptor |

| NKA | Neurokinin A |

| NK-2R | Neurokinin-2 receptor |

| CRH | Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone |

| CGRP | Calcitonin gene-related peptide |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| NPY | Neuropeptide Y |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NOs | Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| GRP | Gastrin Releasing Peptide |

| VIP | Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide |

| PACAP | Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase-Activating Peptide |

| NT3 | Neurotrophin-3 |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| PGP 9.5 | Protein gene product 9.5 |

References

- Grandi, V.; Corsi, A.; Pimpinelli, N.; Bacci, S. Cellular Mechanisms in Acute and Chronic Wounds after PDT Therapy: An Update. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Andersen, C.; Black, J.; de Leon, J.; Fife, C.; Lantis Ii, J.C.; Niezgoda, J.; Snyder, R.; Sumpio, B.; Tettelbach, W.; et al. Management of Chronic Wounds: Diagnosis, Preparation, Treatment, and Follow-up. Wounds 2017, 29, S19–S36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peña, O.A.; Martin, P. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of skin wound healing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naharro-Rodriguez, J.; Bacci, S.; Fernandez-Guarino, M. Molecular Biomarkers in Cutaneous Photodynamic Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guarino, M.; Hernández-Bule, M.L.; Bacci, S. Cellular and Molecular Processes in Wound Healing. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, B.; Vadalà, M.; Laurino, C. Review of the molecular mechanisms in wound healing: New therapeutic targets? J. Wound Care 2017, 26, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Fan, M.; Gao, W. Identification of potential hub genes associated with skin wound healing based on time course bioinformatic analyses. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, T.; Fauzi, M.B.; Lokanathan, Y.; Law, J.X. The Role of Calcium in Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, S.; Nadkarni, S.; Lele, J.; Sakhalkar, S.; Mokashi, P.; Kaushik, K.S. Bioengineered Platforms for Chronic Wound Infection Studies: How Can We Make Them More Human-Relevant? Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziyeva, K.; Kim, Y.; Zharkinbekov, Z.; Kassymbek, K.; Jimi, S.; Saparov, A. Immunology of Acute and Chronic Wound Healing. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilrreff, P.; Alexiev, U. Chronic Inflammation in Non-Healing Skin Wounds and Promising Natural Bioactive Compounds Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, V.; Isseroff, R.R.; Soulika, A.M.; Romanelli, M.; Margolis, D.; Kapp, S.; Granick, M.; Harding, K. Chronic Wounds. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2022, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widgerow, A.D. Chronic wounds—is cellular ‘reception’ at fault? Examining integrins and intracellular signalling. Int. Wound. J. 2013, 10, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, G.S.; Davidson, J.M.; Kirsner, R.S.; Bornstein, P.; Herman, I.M. Dynamic reciprocity in the wound microenvironment. Wound Repair Regen. 2011, 19, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krsek, A.; Ostojic, L.; Zivalj, D.; Baticic, L. Navigating the Neuroimmunomodulation Frontier: Pioneering Approaches Promising Horizons-AComprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, L. Elaborate interactions between the immune and nervous systems. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Baguneid, M.; Bayar, A. The Role of Neuromediators and Innervation in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2016, 96, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosterman, D.; Goerge, T.; Schneider, S.W.; Bunnett, N.W.; Steinhoff, M. Neuronal control of skin function: The skin as a neuroimmunoendocrine organ. Physiol. Rev. 2006, 86, 1309–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chéret, J.; Lebonvallet, N.; Carré, J.; Misery, L.; Le Gall-Ianotto, C. Role of neuropeptides, neurotrophins, and neurohormones in skin wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2013, 21, 772–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverdet, B.; Danigo, A.; Girard, D.; Magy, L.; Demiot, C.; Desmoulière, A. Skin innervation: Important roles during normal and pathological cutaneous repair. Histol. Histopathol. 2015, 30, 875–892. [Google Scholar]

- Kiya, K.; Kubo, T. Neurovascular interactions in skin wound healing. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 125, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszycka, E.; Kwiecien, K.; Kwiecinska, P.; Morytko, A.; Pocalun, N.; Camacho, M.; Brzoza, P.; Zabel, B.A.; Cichy, J. Soluble mediators in the function of the epidermal-immune-neuro unit in the skin. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1003970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, E.; Akhmetshina, M.; Erdiakov, A.; Gavrilova, S. Sympathetic System in Wound Healing: Multistage Control in Normal and Diabetic Skin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, A.; Qubrosi, R.; Cariba, S.; Favaro, K.; Payne, S.L. Neural dependency in wound healing and regeneration. Dev. Dyn. 2024, 253, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El-Aleem, S.A.; Mohammed, H.H.; Saber, E.A.; Embaby, A.S.; Djouhri, L. Mutual inter-regulation between iNOS and TGF-β1: Possible molecular and cellular mechanisms of iNOS in wound healing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siiskonen, H.; Harvima, I. Mast cells and sensory nerves contribute to neurogenic inflammation and pruritus in chronic skin inflammation. Front. Cell. Sci. 2019, 13, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, V.; Paroli, G.; Puliti, E.; Bacci, S.; Pimpinelli, N. Single ALA-PDT irradiation induces increase in mast cells degranulation and neuropeptide acute response in chronic venous ulcers: A pilot study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, P.; Bacci, S. Neuroimmunomodulation in chronic wounds: An opinion. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1562346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Ceilley, R. Chronic Wound Healing: A Review of Current Management and Treatments. Adv. Ther. 2017, 34, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tottoli, E.M.; Dorati, R.; Genta, I.; Chiesa, E.; Pisani, S.; Conti, B. Skin Wound Healing Process and New Emerging Technologies for Skin Wound Care and Regeneration. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Guarino, M.; Bacci, S.; Pérez González, L.A.; Bermejo-Martínez, M.; Cecilia-Matilla, A.; Hernández-Bule, M.L. The Role of Physical Therapies in Wound Healing and Assisted Scarring. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Bule, M.L.; Naharro-Rodríguez, J.; Bacci, S.; Fernández-Guarino, M. Unlocking the Power of Light on the Skin: A Comprehensive Review on Photobiomodulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, J.; Ramos-Milaré, Á.C.F.H.; Lera-Nonose, D.S.S.L.; Nesi-Reis, V.; Demarchi, I.G.; Aristides, S.M.A.; Teixeira, J.J.V.; Silveira, T.G.V.; Lonardoni, M.V.C. Photodynamic therapy in wound healing in vivo: A systematic review. Photodiagnosis Photodynam Ther. 2020, 30, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, V.; Bacci, S.; Corsi, A.; Sessa, M.; Puliti, E.; Murciano, N.; Scavone, F.; Cappugi, P.; Pimpinelli, N. ALA-PDT exerts beneficial effects on chronic venous ulcers by inducing changes in inflammatory microenvironment, especially through increased TGF-beta release: A pilot clinical and translational study. Photodiagnosis Photodynamic Ther. 2018, 21, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wu, L.; Wang, T.; Zhang, F.; Song, J.; Fu, J.; Kong, X.; Shi, J. PTT/ PDT-induced microbial apoptosis and wound healing depend on immune activation and macrophage phenotype transformation. Acta Biomater. 2023, 167, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Lilge, L. Light-based therapy of infected wounds: A review of dose considerations for photodynamic microbial inactivation and photobiomodulation. J. Biomed. Opt. 2025, 30, 030901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Sun, J.; Yang, Y. Research progress of photodynamic therapy in wound healing: A literature review. J. Burn. Care Res. 2023, 44, 1327–1333, Erratum in J. Burn. Care Res. 2024, 45, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Y.G.; Yow, C.M.; Huang, Z. Combination of photodynamic therapy and immunomodulation: Current status and future trends. Med. Res. Rev. 2008, 28, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikziński, P.; Kraus, K.; Seredyński, R.; Widelski, J.; Paluch, E. Photocatalysis and Photodynamic Therapy in Diabetic Foot Ulcers (DFUs) Care: A Novel Approach to Infection Control and Tissue Regeneration. Molecules 2025, 26, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algorri, J.F.; Ochoa, M.; Roldán-Varona, P.; Rodríguez-Cobo, L.; López-Higuera, J.M. Light Technology for Efficient and Effective Photodynamic Therapy: A Critical Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cheng, W.; Tian, H.; Dong, M.; He, W.; Wang, X.; Zou, Y. Thymopentin-integrated self-assembling nanoplatform for enhanced photo-immunotherapy in diabetic wound healing. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 699, 138264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xie, H.; Zhang, J.; Tang, C.; Tian, S.; Yuan, P.; Sun, C.; Cui, C.; Zhong, Q.; Xu, F.; et al. Hydrogel-Based Sequential Photodynamic Therapy Promotes Wound Healing by Targeting Wound Infection and Inflammation. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 12107–12117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, H.W.; Yuan, K.H.; Li, F.L.; Huang, Z. Combination of photodynamic therapy and immunomodulation for skin diseases--update of clinical aspects. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2011, 10, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fernandez-Guarino, M.; de Salinas, L.A.-M.; Naharro-Rodriguez, J.; Bacci, S. An Update on the Correlation Between Neuroimmunomodulation, Photodynamic Therapy (PDT), and Wound Healing: The Role of Mast Cells. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020280

Fernandez-Guarino M, de Salinas LA-M, Naharro-Rodriguez J, Bacci S. An Update on the Correlation Between Neuroimmunomodulation, Photodynamic Therapy (PDT), and Wound Healing: The Role of Mast Cells. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(2):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020280

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernandez-Guarino, Montserrat, Luis Alonso-Mtz de Salinas, Jorge Naharro-Rodriguez, and Stefano Bacci. 2026. "An Update on the Correlation Between Neuroimmunomodulation, Photodynamic Therapy (PDT), and Wound Healing: The Role of Mast Cells" Biomedicines 14, no. 2: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020280

APA StyleFernandez-Guarino, M., de Salinas, L. A.-M., Naharro-Rodriguez, J., & Bacci, S. (2026). An Update on the Correlation Between Neuroimmunomodulation, Photodynamic Therapy (PDT), and Wound Healing: The Role of Mast Cells. Biomedicines, 14(2), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14020280