Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Alleviates Headache Symptoms in Migraine Model Mice by the Locus Coeruleus/Noradrenergic System: An Experimental Study in a Mouse Model of Migraine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Grouping

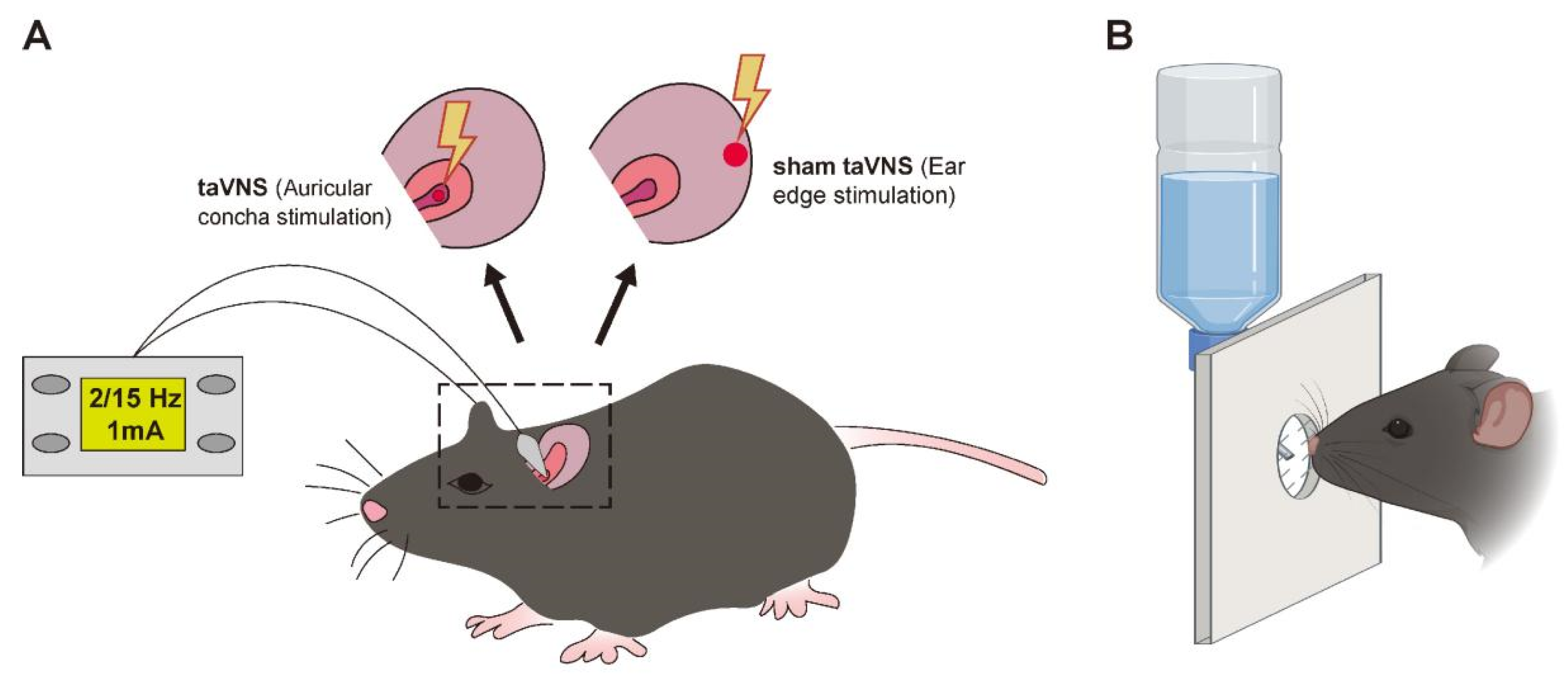

2.1.1. Model Establishment

2.1.2. TaVNS Intervention Method

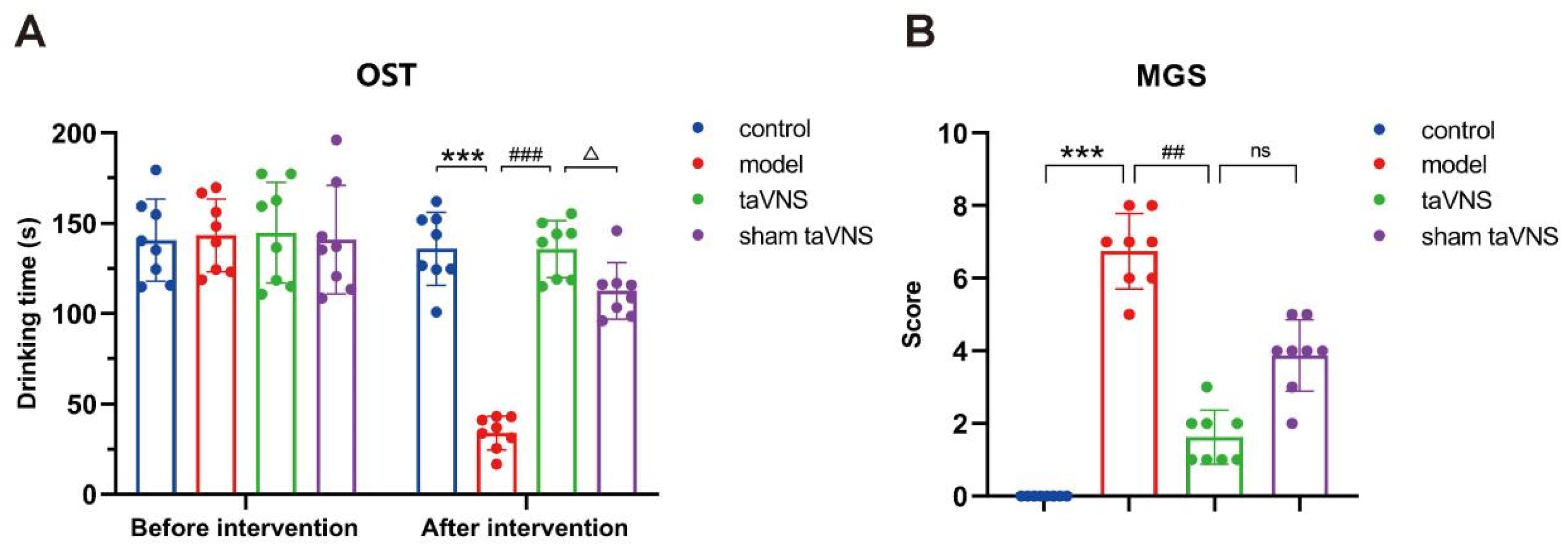

2.1.3. The Orofacial Stimulation Test (OST)

2.2. The Mouse Grimace Scale (MGS)

2.3. Immunofluorescence

2.4. Western Blot

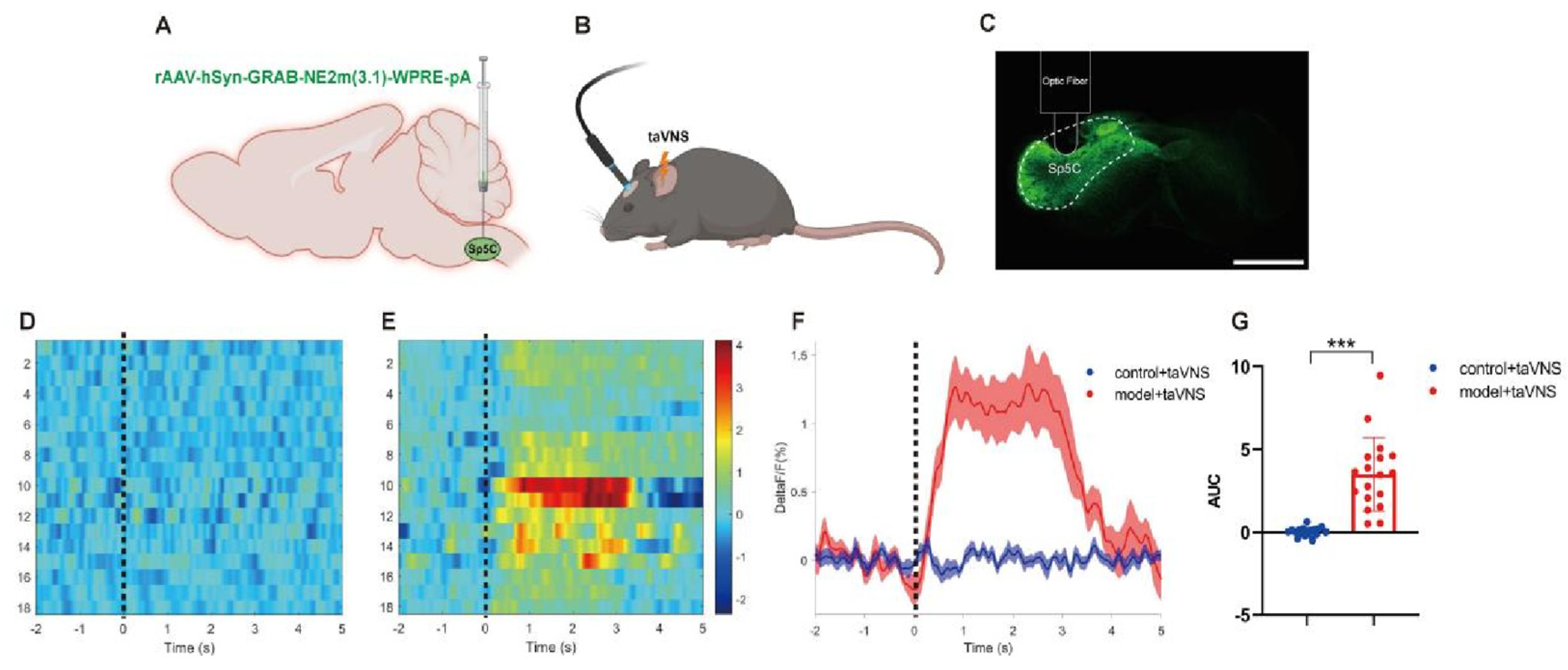

2.5. Fiber Photometry Recording

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Behavioral Experimental Results Among Groups of Mice

3.2. Comparison of the Number of Norepinephrine (NE) Neurons in the Locus Coeruleus (LC) Among the Groups of Mice

3.3. Comparison of NE Release in the Spinal Trigeminal Nucleus Caudalis (Sp5C) Among the Groups of Mice

3.4. Comparison of α-2A Adrenergic Receptor (α-2AAR) Protein Expression in the Sp5C Among the Groups of Mice

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| taVNS | transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation |

| LC | locus coeruleus |

| OST | orofacial stimulation test |

| MGC | mouse grimace scale |

| Sp5C | spinal trigeminal nucleus caudalis |

| VNS | vagus nerve stimulation |

| NTS | nucleus solitarius |

| NE | norepinephrine |

| α-2AAR | α-2A adrenergic receptor |

| NTG | nitroglycerin |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| TBST | tris-buffered saline with tween 20 |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| RIPA | radio immunoprecipitation assay |

| SDS-PAGE | sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| IgG-HRP | immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase |

| ECL | enhanced chemiluminescence |

| LC-NE | locus coeruleus–norepinephrine |

References

- GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 954–976, Erratum in Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00380-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deodato, M.; Granato, A.; Martini, M.; Stella, A.B.; Galmonte, A.; Murena, L.; Manganotti, P. Neurophysiological and Clinical Outcomes in Episodic Migraine Without Aura: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2024, 41, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J. Epidemiology of migraine and other types of headache in Asia. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2003, 3, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, H.C.; Dodick, D.W.; Goadsby, P.J.; Lipton, R.B.; Olesen, J.; Silberstein, S.D. Chronic migraine--classification, characteristics and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shen, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C. Auricular acupuncture for migraine: A systematic review protocol. Medicine 2020, 99, e18900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goertz, C.M.; Niemtzow, R.; Burns, S.M.; Fritts, M.J.; Crawford, C.C.; Jonas, W.B. Auricular acupuncture in the treatment of acute pain syndromes: A pilot study. Mil. Med. 2006, 171, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romoli, M.; Allais, G.; Airola, G.; Benedetto, C. Ear acupuncture in the control of migraine pain: Selecting the right acupoints by the “needle-contact test”. Neurol. Sci. 2005, 26 (Suppl. 2), s158–s161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.H.; Rong, P.J.; Chen, Y.; Song, X.K.; Wang, J.Y. Possible mechanisms of auricular acupoint stimulation in the treatment of migraine by activating auricular vagus nerve. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu 2024, 49, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austelle, C.W.; Cox, S.S.; Wills, K.E.; Badran, B.W. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS): Recent advances and future directions. Clin Auton Res. 2024, 34, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V.; Gianlorenço, A.C.; Andrade, M.F.; Camargo, L.; Menacho, M.; Avila, M.A.; Pacheco-Barrios, K.; Choi, H.; Song, J.J.; Fregni, F. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation effects on chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Rep. 2024, 9, e1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Hou, X.; Chen, W.; Tu, Y.; Hodges, S.; et al. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS) for migraine: An fMRI study. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021, 46, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Kuang, C.; Huang, H.; Jiao, B.; Ma, L.; Lin, J. Altered functional brain network patterns in patients with migraine without aura after transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Park, J.; Wilson, G.; Liu, B.; Kong, J. Transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation at 1 Hz modulates locus coeruleus activity and resting state functional connectivity in patients with migraine: An fMRI study. NeuroImage Clin. 2019, 24, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straube, A.; Ellrich, J.; Eren, O.; Blum, B.; Ruscheweyh, R. Treatment of chronic migraine with transcutaneous stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (auricular t-VNS): A randomized, monocentric clinical trial. J. Headache Pain 2015, 16, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.F.; Albusoda, A.; Farmer, A.D.; Aziz, Q. The anatomical basis for transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation. J. Anat. 2020, 236, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangos, E.; Ellrich, J.; Komisaruk, B.R. Non-invasive Access to the Vagus Nerve Central Projections via Electrical Stimulation of the External Ear: fMRI Evidence in Humans. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hodges, S.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Liu, X.; Hou, X.; Chen, W.; Chai-Zhang, T.; Kong, J.; et al. The modulation effects of repeated transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on the functional connectivity of key brainstem regions along the vagus nerve pathway in migraine patients. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1160006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacca, V.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Ye, Y.; Hou, X.; McDonald, C.M.; Todorova, N.; Kong, J.; et al. Evaluation of the Modulation Effects Evoked by Different Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Frequencies Along the Central Vagus Nerve Pathway in Migraine: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Neuromodulation Technol. Neural Interface 2023, 26, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vila-Pueyo, M.; Strother, L.C.; Kefel, M.; Goadsby, P.J.; Holland, P.R. Divergent influences of the locus coeruleus on migraine pathophysiology. Pain 2019, 160, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón-Alarcón, D.; Cabañero, D.; de Andrés-López, J.; Nikolaeva-Koleva, M.; Giorgi, S.; Fernández-Ballester, G.; Fernández-Carvajal, A.; Ferrer-Montiel, A. TRPM8 contributes to sex dimorphism by promoting recovery of normal sensitivity in a mouse model of chronic migraine. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhu, H.; Song, X.; Hou, L.; Wang, L.; et al. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Stimulation Attenuates LPS-Induced Depression-Like Behavior by Regulating Central α7nAChR/JAK2 Signaling. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 3011–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibault, K.; Rivière, S.; Lenkei, Z.; Férézou, I.; Pezet, S. Orofacial Neuropathic Pain Leads to a Hyporesponsive Barrel Cortex with Enhanced Structural Synaptic Plasticity. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, D.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Chanda, M.L.; Clarke, S.E.; Drummond, T.E.; Echols, S.; Glick, S.; Ingrao, J.; Klassen-Ross, T.; LaCroix-Fralish, M.L.; et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, B.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X. The abnormally increased functional connectivity of the locus coeruleus in migraine without aura patients. BMC Res. Notes 2024, 17, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, R. Antidepressants for Preventive Treatment of Migraine. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2019, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, I.; Johns, M.A.; Pandža, N.B.; Calloway, R.C.; Karuzis, V.P.; Kuchinsky, S.E. Three Hundred Hertz Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation (taVNS) Impacts Pupil Size Non-Linearly as a Function of Intensity. Psychophysiology 2025, 62, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, M.; Wienke, C.; Betts, M.J.; Zaehle, T.; Hämmerer, D. Current challenges in reliably targeting the noradrenergic locus coeruleus using transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation (taVNS). Auton. Neurosci. 2021, 236, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.L.; Gebhart, G.F. Spinal pathways mediating tonic, coeruleospinal, and raphe-spinal descending inhibition in the rat. J. Neurophysiol. 1987, 58, 138–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howorth, P.W.; Teschemacher, A.G.; Pickering, A.E. Retrograde adenoviral vector targeting of nociresponsive pontospinal noradrenergic neurons in the rat in vivo. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009, 512, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, M.J. Descending control of pain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2002, 66, 355–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.; Xue, X.; Jiao, Y.; Du, M.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, X.; Sun, J.B.; Qin, W.; Deng, H.; Yang, X.J. Can earlobe stimulation serve as a sham for transcutaneous auricular vagus stimulation? Evidence from an alertness study following sleep deprivation. Psychophysiology 2025, 62, e14744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Score | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eyes (degree of eye opening) | Eyes fully open | Eyes partially closed | Eyes fully closed or squinted |

| Nose (nasal ridge) | Smooth nasal ridge | Slightly raised nasal ridge | Prominent nasal ridge |

| Cheeks (cheek puffing) | Flat cheeks | Slightly puffed cheeks | Clearly puffed cheeks |

| Ears (orientation to the sides) | Ears naturally relaxed | Ears tilted outward | Increased gap between the ears |

| Whiskers (upright) | Whiskers relaxed, slightly drooping | Whiskers tilted backward | Whisker pads contracted, whiskers upright |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Song, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, H.; Rong, P.; Zhang, J.; Pu, X.; Wang, J. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Alleviates Headache Symptoms in Migraine Model Mice by the Locus Coeruleus/Noradrenergic System: An Experimental Study in a Mouse Model of Migraine. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010096

Song X, Chen Z, Zhu H, Rong P, Zhang J, Pu X, Wang J. Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Alleviates Headache Symptoms in Migraine Model Mice by the Locus Coeruleus/Noradrenergic System: An Experimental Study in a Mouse Model of Migraine. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Xingke, Zijie Chen, Haohan Zhu, Peijing Rong, Jinling Zhang, Xue Pu, and Junying Wang. 2026. "Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Alleviates Headache Symptoms in Migraine Model Mice by the Locus Coeruleus/Noradrenergic System: An Experimental Study in a Mouse Model of Migraine" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010096

APA StyleSong, X., Chen, Z., Zhu, H., Rong, P., Zhang, J., Pu, X., & Wang, J. (2026). Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Alleviates Headache Symptoms in Migraine Model Mice by the Locus Coeruleus/Noradrenergic System: An Experimental Study in a Mouse Model of Migraine. Biomedicines, 14(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010096