Next-Generation SGLT2 Inhibitors: Innovations and Clinical Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Next-Generation SGLT2-Based Inhibitors: Developmental Status and Clinical Evidence

1.2. Sotagliflozin (Dual SGLT1/SGLT2 Inhibitor)

1.3. Licogliflozin (Dual SGLT1/SGLT2 Inhibitor)

1.4. Emerging and Experimental Approaches

1.5. Comparative Efficacy: Current Limitations

2. Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes

2.1. Cardiovascular Outcome Evidence

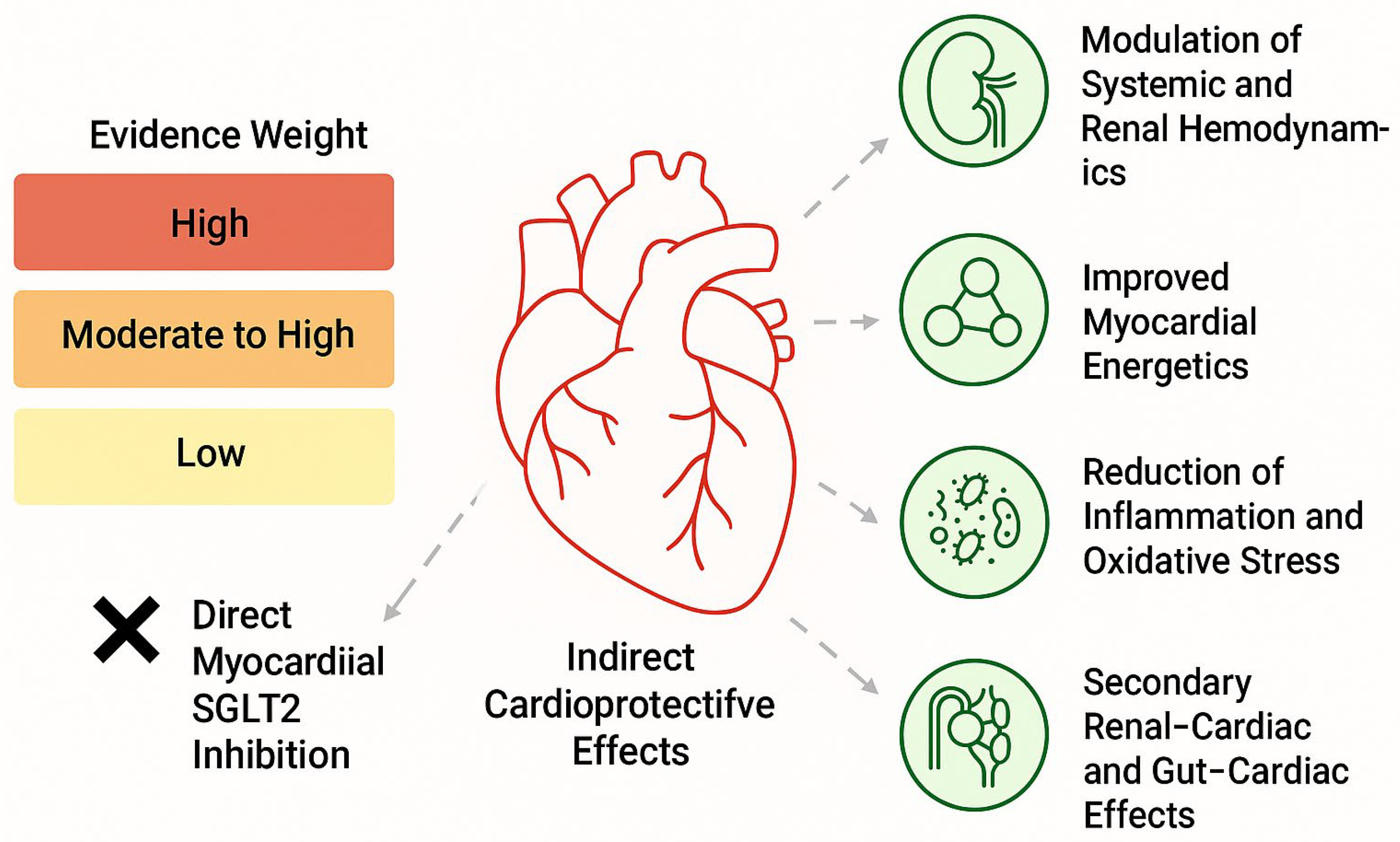

2.2. Direct Myocardial SGLT2 Inhibition: Evidence and Controversy

2.3. Methodological Sources of Heterogeneity

2.4. Indirect and Glucose-Independent Mechanisms of Cardioprotection

- Osmotic diuresis and natriuresis leading to hemodynamic unloading;

- Improved myocardial energetics through increased ketone body availability;

- Modulation of intracellular sodium and calcium handling, potentially via effects on the Na+/H+ exchanger;

- Attenuation of inflammation, oxidative stress, and myocardial fibrosis;

- Secondary effects mediated through renal–cardiac and gut–cardiac axes, including reductions in hyperuricemia, improved endothelial function, and changes in erythropoietin signaling [24].

2.5. Interpretative Framework

2.6. Heart Failure Outcomes: Effect Size, Timing, and Mechanistic Interpretation

2.7. Trial-Level Limitations and Interpretation

2.8. Early Initiation and Interaction with Diuretic Therapy

2.9. Mechanistic Hypotheses: Evidence and Caution

2.10. Integrative Perspective

3. SGLT2 Inhibitors in Acute and Chronic Heart Failure

3.1. Clinical Evidence Across the Heart Failure Spectrum

3.2. Early Initiation in Acute Heart Failure

3.3. Mechanistic Basis of Heart Failure Benefit

3.4. Post–Myocardial Infarction States

3.5. Differential Pathophysiology of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure

3.6. Shared and Condition-Specific Mechanisms of SGLT2 Inhibition

3.7. Integrative Perspective

4. Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Renal Outcomes

4.1. Mechanistic Basis of Renoprotection: A Hierarchical Framework

4.2. Next-Generation SGLT2-Based Therapies and Renal Implications

4.3. Expanded Indications and Ongoing Research

4.4. Renal Outcomes: Clinical Effect Size, eGFR Contextualization, and Mechanistic Hierarchy

4.5. Clinical Interpretation of eGFR Thresholds

4.6. Hierarchical Organization of Renoprotective Mechanisms

4.7. Primary Mechanisms (Strong Human Clinical Evidence)

- Restoration of tubuloglomerular feedback and reduction in intraglomerular pressure;

- Hemodynamic stabilization of glomerular filtration;

- Reduction in albuminuria, strongly correlated with long-term renal outcomes.

4.8. Secondary Mechanisms (Supported by Translational and Indirect Clinical Data)

- Improved renal oxygenation through reduced proximal tubular workload;

- Attenuation of renal inflammation and oxidative stress;

- Modulation of renal hemodynamics within the cardiorenal axis.

4.9. Exploratory Mechanisms (Predominantly Preclinical Evidence)

4.10. Expanded Indications of SGLT2 Inhibitors: Evidence, Guidelines, and Implementation Challenges

4.11. Guideline-Supported Expansion of Indications

4.12. Acute and Early Use: EMPULSE Trial in Context

4.13. Terminology and Evidence Thresholds

4.14. Cost-Effectiveness and Access Considerations

4.15. Timing of SGLT2 Inhibitor Initiation in Relation to TAVI: Hemodynamics, Risk, and Remodeling

4.16. Pre-TAVI Initiation: Hemodynamic Vulnerability

4.17. Peri-Procedural Considerations: Procedural Risk and Renal Protection

4.18. Post-TAVI Initiation: Reverse Remodeling and Stabilization

- Optimization of heart failure therapy;

- Reduction in residual congestion;

- Renal protection during remodeling;

- Metabolic efficiency during myocardial recovery [74].

4.19. Integrative Perspective

5. Conclusions

5.1. Pleiotropic and Emerging Biological Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors

5.2. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonner, C.; Kerr-Conte, J.; Gmyr, V.; Queniat, G.; Moerman, E.; Thévenet, J.; Beaucamps, C.; Delalleau, N.; Popescu, I.; Malaisse, W.J.; et al. Inhibition of the glucose transporter SGLT2 with dapagliflozin in pancreatic alpha cells triggers glucagon secretion. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, M.S.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Anker, S.D.; Bakris, G.L.; Bhatt, D.L.; Filippatos, G.; Fonarow, G.C.; Greene, S.J.; Januzzi, J.L., Jr.; Khan, M.S.; et al. Effect of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Cardiovascular Outcomes Across Various Patient Populations. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 2377–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scisciola, L.; Paolisso, P.; Belmonte, M.; Gallinoro, E.; Delrue, L.; Taktaz, F.; Fontanella, R.A.; Degrieck, I.; Pesapane, A.; Casselman, F.; et al. Myocardial sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 expression and cardiac remodelling in patients with severe aortic stenosis: The BIO-AS study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madaan, T.; Akhtar, M.; Najmi, A.K. Sodium glucose CoTransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors: Current status and future perspective. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 93, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, M.; Di Nora, C.; De Maria, R.; Mousavi, A.H.; Carigi, S.; De Gennaro, L.; Manca, P.; Matassini, M.V.; Rizzello, V.; Tinti, M.D.; et al. SGLT2-is in Acute Heart Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Alam, U.; Barber, T.M.; Karalliedde, J.; Cuthbertson, D.J. The expanding role of SGLT2 inhibitors beyond glucose-lowering to cardiorenal protection. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 2072–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.C.; Zheng, C.M.; Yen, T.H.; Lu, K.C. Molecular Mechanisms of SGLT2 Inhibitor on Cardiorenal Protection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallon, V. State-of-the-Art-Review: Mechanisms of Action of SGLT2 Inhibitors and Clinical Implications. Am. J. Hypertens. 2024, 37, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaduganathan, M.; Docherty, K.F.; Claggett, B.L.; Jhund, P.S.; de Boer, R.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure: A comprehensive meta-analysis of five randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2022, 400, 757–767, Erratum in Lancet 2023, 401, 104.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Szarek, M.; Cannon, C.P.; Leiter, L.A.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Lopes, R.D.; McGuire, D.K.; Lewis, J.B.; Riddle, M.C.; et al. Effect of sotagliflozin on major adverse cardiovascular events: A prespecified secondary analysis of the SCORED randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrul-Hasan, A.; Mondal, S.; Zahura Aalpona, F.T.; Nagendra, L.; Dutta, D. Role of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors in Managing Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Systematic Review. touchREV Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.T.K.; Wong, C.K.H.; Au, I.C.H.; Lau, W.C.Y.; Man, K.K.C.; Chui, C.S.L.; Wong, I.C.K. Switching to Versus Addition of Incretin-Based Drugs Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Taking Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorboulev, V.; Schürmann, A.; Vallon, V.; Kipp, H.; Jaschke, A.; Klessen, D.; Friedrich, A.; Scherneck, S.; Rieg, T.; Cunard, R.; et al. Na+-D-glucose cotransporter SGLT1 is pivotal for intestinal glucose absorption and glucose-dependent incretin secretion. Diabetes 2012, 61, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inzucchi, S.E.; Zinman, B.; Fitchett, D.; Wanner, C.; Ferrannini, E.; Schumacher, M.; Schmoor, C.; Ohneberg, K.; Johansen, O.E.; George, J.T.; et al. How Does Empagliflozin Reduce Cardiovascular Mortality? Insights From a Mediation Analysis of the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Trial. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 356–363. [Google Scholar]

- Fitchett, D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Schumacher, M.; Schmoor, C.; Ohneberg, K.; Ofstad, A.P.; Salsali, A.; George, J.T.; et al. Mediators of the improvement in heart failure outcomes with empagliflozin in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 4517–4527. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Tang, T.; Yu, Q.; Tong, X.; You, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Tang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; et al. Cardiovascular Outcome of the SGLT2 Inhibitor in Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 26136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfella, R.; Scisciola, L.; D’Onofrio, N.; Maiello, C.; Trotta, M.C.; Sardu, C.; Panarese, I.; Ferraraccio, F.; Capuano, A.; Barbieri, M.; et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) expression in diabetic and non-diabetic failing human cardiomyocytes. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 184, 106448. [Google Scholar]

- Paolisso, P.; Belmonte, M.; Gallinoro, E.; Scarsini, R.; Bergamaschi, L.; Portolan, L.; Armillotta, M.; Esposito, G.; Moscarella, E.; Benfari, G.; et al. SGLT2-inhibitors in diabetic patients with severe aortic stenosis and cardiac damage undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 420, Erratum in Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 14.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposeiras-Roubin, S.; Amat-Santos, I.J.; Rossello, X.; González Ferreiro, R.; González Bermúdez, I.; Lopez Otero, D.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Gheorghe, L.; Diez, J.L.; Baladrón Zorita, C.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, T.; Zhang, Z.; Shah, H.; Fanaroff, A.C.; Nathan, A.S.; Parise, H.; Lutz, J.; Sugeng, L.; Bellumkonda, L.; Redfors, B.; et al. Effect of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors on the Progression of Aortic Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2025, 18, 738–748. [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste, T.M.G.; Rodero, C.; Sillett, C.P.; Strocchi, M.; Lanyon, C.W.; Augustin, C.M.; Lee, A.W.C.; Solís-Lemus, J.A.; Roney, C.H.; Ennis, D.B.; et al. Regional heterogeneity in left atrial stiffness impacts passive deformation in a cohort of patient-specific models. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1013656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J.; Herat, L.; Schlaich, M.P.; Matthews, V. The Impact of SGLT2 Inhibitors in the Heart and Kidneys Regardless of Diabetes Status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndumele, C.E.; Rangaswami, J.; Chow, S.L.; Neeland, I.J.; Tuttle, K.R.; Khan, S.S.; Coresh, J.; Mathew, R.O.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Carnethon, M.R.; et al. Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 148, 1606–1635, Erratum in Circulation 2024, 149, e1023.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curaj, A.; Vanholder, R.; Loscalzo, J.; Quach, K.; Wu, Z.; Jankowski, V.; Jankowski, J. Cardiovascular Consequences of Uremic Metabolites: An Overview of the Involved Signaling Pathways. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Coronel, R.; Hollmann, M.W.; Weber, N.C.; Zuurbier, C.J. Direct cardiac effects of SGLT2 inhibitors. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Lee, Y.A.; Bian, J.; Guo, J. Heterogeneous Effects of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors on Acute Kidney Injury: A Causal Learning Approach. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebi, R.; Liu, Y.; Felker, G.M.; Prescott, M.F.; Ward, J.H.; PiÑA, I.L.; Butler, J.; Solomon, S.D.; Januzzi, J.L. Heart Failure Duration and Mechanistic Efficacy of Sacubitril/Valsartan in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. J. Card. Fail. 2022, 28, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Januzzi, J.L.; Ferreira, J.P.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Brueckmann, M.; Jamal, W.; Cotton, D.; et al. Concentration-dependent clinical and prognostic importance of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T in heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction and the influence of empagliflozin: The EMPEROR-Reduced trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 1529–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; Shah, S.J.; Lindholm, D.; et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with preserved and mildly reduced ejection fraction: Rationale and design of the DELIVER trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 1217–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voors, A.A.; Angermann, C.E.; Teerlink, J.R.; Collins, S.P.; Kosiborod, M.; Biegus, J.; Ferreira, J.P.; Nassif, M.E.; Psotka, M.A.; Tromp, J.; et al. The SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients hospitalized for acute heart failure: A multinational randomized trial. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffaello, W.; Henrina, J.; Huang, I.; Lim, M.; Suciadi, L.; Siswanto, B.; Pranata, R. Clinical Characteristics of De Novo Heart Failure and Acute Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure: Are They Distinctive Phenotypes That Contribute to Different Outcomes? Card. Fail. Rev. 2021, 7, e02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzotta, R.; Garofalo, M.; Salvi, S.; Orlandi, M.; Marcaccini, G.; Susini, P.; Checchi, L.; Palazzuoli, A.; Di Mario, C.; Pieroni, M.; et al. Early administration of SGLT2 inhibitors in hospitalized patients: A practical guidance from the current evidence. ESC Heart Fail. 2025, 12, 2631–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, P.; Bennett, J.; Trey Woods, E.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Newman, N.; Mohammad, Y.; Khawaja, M.; Rizwan, A.; Siddiqui, R.; Birnbaum, Y.; et al. SGLT2 inhibitors across various patient populations in the era of precision medicine: The multidisciplinary team approach. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, A.; Montecucco, F.; Carbone, F.; Camici, G.G.; Lüscher, T.F.; Kraler, S.; Liberale, L. SGLT2 inhibitors: From glucose-lowering to cardiovascular benefits. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Mosenzon, O.; Kato, E.T.; Cahn, A.; Silverman, M.G.; Zelniker, T.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wei, Q.; Zou, A.; Yu, K.; Song, D.; Li, J.; Han, H.; Liu, A. Evaluation of three mechanisms of action (SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and sulfonylureas) in treating type 2 diabetes with heart failure: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of RCTs. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1562815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Olewinska, E.; Famulska, A.; Remuzat, C.; Francois, C.; Folkerts, K. Heart failure with mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction: A review of disease burden and remaining unmet medical needs within a new treatment landscape. Heart Fail. Rev. 2024, 29, 631–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbi, M.; Lairez, O.; Baudry, G.; Gautier, P.; Roubille, F.; Delmas, C. Early Initiation of Sodium–Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors in Acute Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Orozco, H.; Voorrips, S.N.; Yurista, S.R.; de Boer, R.A.; Westenbrink, B.D. SGLT2 Inhibitors and Ketone Metabolism in Heart Failure. J. Lipid Atheroscler. 2022, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, R. NLRP3 inflammasome in neuroinflammation and central nervous system diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.L.; Wang, H.; Ouyang, D.; Qi, H.; Li, X.H. The impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1699066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svanström, H.; Mkoma, G.F.; Hviid, A.; Pasternak, B. SGLT-2 inhibitors and mortality among patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Linked database study. BMJ 2024, 387, e080925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semirani-Nezhad, D.; Soleimani, H.; Taebi, M.; Roozbehi, K.; Jahangiri, S.; Sattartabar, B.; Takaloo, F.; Parastooei, B.; Asfa, E.; Salabat, D.; et al. Early initiation of SGLT2 inhibitors in acute myocardial infarction and cardiovascular outcomes, an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, M.; Jessup, M.; Mullens, W.; Reza, N.; Shah, A.M.; Sliwa, K.; Mebazaa, A. Acute heart failure. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, R.H.G. Pathophysiology of heart failure. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2021, 11, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispino, S.P.; Segreti, A.; Nafisio, V.; Valente, D.; Crisci, F.; Ferro, A.; Cavallari, I.; Nusca, A.; Ussia, G.P.; Grigioni, F. The Role of SGLT2-Inhibitors Across All Stages of Heart Failure and Mechanisms of Early Clinical Benefit: From Prevention to Advanced Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Fang, T.; Cheng, Z. Mechanism of heart failure after myocardial infarction. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 3000605231202573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.B. Mechanistic Insights of SGLT2 Inhibition in Heart Failure Through Proteomics: Appreciating the Cardiovascular-Kidney Connection. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 1995–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.R.; Elkhatib, M.; El-Khashab, S.; Darwish, R.A.; Fayed, A.; Abdelaziz, T.S.; Hammad, H.; Ahmed, R.M.; Maamoun, H.A. Dual-faced guardians: SGLT2 inhibitors’ kidney protection and health challenges: A position statement by Kasralainy nephrology group (KANG). Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2025, 17, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, P.B.; Sarafidis, P.; Ekart, R.; Ferro, C.J.; Balafa, O.; Fernandez-Fernandez, B.; Herrington, W.G.; Rossignol, P.; Del Vecchio, L.; Valdivielso, J.M.; et al. SGLT2i for evidence-based cardiorenal protection in diabetic and non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: A comprehensive review by EURECA-m and ERBP working groups of ERA. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 2444–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkovic, V.; Jardine, M.J.; Neal, B.; Bompoint, S.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Charytan, D.M.; Edwards, R.; Agarwal, R.; Bakris, G.; Bull, S.; et al. Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Empagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Stefánsson, B.V.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Chertow, G.M.; Greene, T.; Hou, F.-F.; Mann, J.F.E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lindberg, M.; Rossing, P.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checa-Ros, A.; Okojie, O.J.; D’Marco, L. SGLT2 Inhibitors: Multifaceted Therapeutic Agents in Cardiometabolic and Renal Diseases. Metabolites 2025, 15, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, R.M.; Dungo, R.T. Ipragliflozin: First Global Approval. Drugs 2014, 74, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Kozlovski, P.; Shao, Q.; Proot, P.; Keefe, D. Licogliflozin, a Novel SGLT1 and 2 Inhibitor: Body Weight Effects in a Randomized Trial in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. Obesity 2020, 28, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.; Boer, R.A.d.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Rocca, H.-P.B.L.; Choi, D.-J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Guo, Y.; Lin, Y.; Gao, H.; Ren, H. Impact of Empagliflozin on Cardiovascular Outcomes and Renal Function in Patients with Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diabetes Ther. 2025, 16, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosiborod, M.N.; Angermann, C.E.; Collins, S.P.; Teerlink, J.R.; Ponikowski, P.; Biegus, J.; Comin-Colet, J.; Ferreira, J.P.; Mentz, R.J.; Nassif, M.E.; et al. Effects of Empagliflozin on Symptoms, Physical Limitations, and Quality of Life in Patients Hospitalized for Acute Heart Failure: Results From the EMPULSE Trial. Circulation 2022, 146, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podestà, M.A.; Sabiu, G.; Galassi, A.; Ciceri, P.; Cozzolino, M. SGLT2 Inhibitors in Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Chronic Kidney Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney, D.Z.I.; Verma, S. DAPA-CKD: The Beginning of a New Era in Renal Protection. JACC Basic. Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Mo, W.; Ling, Z.; Hou, L.; Deng, T. Efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors on acute kidney injury in patients with chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2025, 117, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherney David, Z.; Odutayo, A.; Aronson, R.; Ezekowitz, J.; Parker John, D. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibition and Cardiorenal Protection. JACC 2019, 74, 2511–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, A.; Kitada, K. Possible renoprotective mechanisms of SGLT2 inhibitors. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1115413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Nguyen, T.V. Expanding the Role of SGLT2 Inhibitors Beyond Diabetes: A Case-Based Approach. Sr. Care Pharm. 2023, 38, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biegus, J.; Voors, A.A.; Collins, S.P.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Teerlink, J.R.; Angermann, C.E.; Tromp, J.; Ferreira, J.P.; Nassif, M.E.; Psotka, M.A.; et al. Impact of empagliflozin on decongestion in acute heart failure: The EMPULSE trial. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttone, A.; Cannavò, V.; Abdullah, R.M.S.; Fugazzotto, P.; Arena, G.; Brancati, S.; Muscarà, A.; Morace, C.; Quartarone, C.; Ruggeri, D.; et al. Expanding the Use of SGLT2 Inhibitors in T2D Patients Across Clinical Settings. Cells 2025, 14, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hoogenveen, R.; El Alili, M.; Knies, S.; Wang, J.; Beulens, J.W.J.; Elders, P.J.M.; Nijpels, G.; van Giessen, A.; Feenstra, T.L. Cost-Effectiveness of SGLT2 Inhibitors in a Real-World Population: A MICADO Model-Based Analysis Using Routine Data from a GP Registry. Pharmacoeconomics 2023, 41, 1249–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Y.; Shah, B.R.; Sharma, A.; Sheng, Y.; Liu, P.P.; Kopp, A.; Saskin, R.; Edwards, J.D.; Swardfager, W. Timing of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor initiation and post-discharge outcomes in acute heart failure with diabetes: A population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2025, 27, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyman, S.N.; Aronson, D.; Abassi, Z. SGLT2 Inhibitors and the Risk of Contrast-Associated Nephropathy Following Angiographic Intervention: Contradictory Concepts and Clinical Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Wang, H.; Liao, H.; Yan, F.; Shi, F.; Liu, S. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation improves left ventricular function and hemodynamics and reduces severe ventricular arrhythmias in patients with severe aortic stenosis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Park, G.; Lee, K.; Jang, H.R.; Lee, J.E.; Huh, W.; Jeon, J. SGLT2 inhibitor use and renal outcomes in low-risk population with diabetes mellitus and normal or low body mass index. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2025, 13, e004876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimaille, A.; Marchandot, B.; Morel, O. SGLT2 Inhibition After Aortic Valve Replacement: The Role of the Native Valve. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, T.; Galiero, R.; Caturano, A.; Rinaldi, L.; Di Martino, A.; Albanese, G.; Di Salvo, J.; Epifani, R.; Marfella, R.; Docimo, G.; et al. An Overview of the Cardiorenal Protective Mechanisms of SGLT2 Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.S.; Dandamudi, M.; Rehman, T.; Faizan, M.A.; Zahra, I.; Mojica, J.C.; Ahmed, M.R.; Bai, K.; Shakeel, I.; Shahzad, Z.; et al. “Efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors in non-diabetic non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2025, 24, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, D. SGLT2 inhibitors as metabolic modulators: Beyond glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1601633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Agent | Transporter Profile | Regulatory Status | Clinical Phase | Key Trials | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sotagliflozin | SGLT1/SGLT2 | Approved (region/indication-specific) | Phase III completed | SOLOIST-WHF (~1200); SCORED (~10,500) | HF, CKD, CV risk |

| Licogliflozin | SGLT1/SGLT2 | Not approved | Phase II | Multiple small RCTs (<300) | Metabolic/HFpEF |

| Emerging agents | SGLT2-based | Not approved | Phase I–II | Early studies | Precision therapy |

| Study Type/Reference | Species/Tissue | Sample Size | Methodology | Key Findings | Major Limitations | Interpretative Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry studies (early reports) | Rodent myocardium/neonatal cardiomyocytes | Small (n < 10) | IHC using commercial antibodies | Detectable SGLT2 signal in cardiomyocytes | Antibody cross-reactivity; non-human tissue; neonatal cells | Hypothesis-generating only |

| Western blot analyses | Rodent or diseased human myocardium | Small (n < 15) | Western blot | Low-level SGLT2 protein bands | Lack of validated controls; possible non-specific binding | Low |

| RT-PCR–based studies | Diseased human myocardial samples | Small (n < 20) | RT-PCR | Low or variable SGLT2 mRNA expression | High Ct values; sampling bias; atrial vs. ventricular tissue | Low |

| Bulk RNA sequencing | Adult human left ventricular myocardium | Moderate–large | Transcriptomic profiling | Minimal or absent SGLT2 transcripts | Detection threshold limitations | Moderate–high (negative evidence) |

| Single-cell RNA sequencing | Adult human cardiomyocytes | Large datasets | scRNA-seq | No consistent SGLT2 expression in cardiomyocytes | Dropout effects inherent to scRNA-seq | High |

| Proteomic analyses | Adult human myocardium | Moderate | Mass spectrometry | No detectable SGLT2 protein | Sensitivity limits for low-abundance proteins | High |

| Comparative renal–cardiac expression studies | Human kidney vs. myocardium | Moderate | Multi-tissue profiling | Marked SGLT2 expression in kidney, absent in heart | None significant | High |

| Feature | Conventional SGLT2i | Next-Generation SGLT2i |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical backbone | C-aryl glucoside | Modified glucoside/hybrid |

| SGLT2 selectivity | High | Ultra-high or dual |

| SGLT1 inhibition | Minimal | Partial (agent-specific) |

| PK profile | Standard | Optimized/prolonged |

| Tissue distribution | Predominantly renal | Multi-organ |

| Agent | Target | Key Trials | Novel Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dapagliflozin | SGLT2 | DAPA-HF, DAPA-CKD | HF, CKD |

| Empagliflozin | SGLT2 | EMPEROR, EMPA-KIDNEY | HFpEF |

| Sotagliflozin | SGLT1/2 | SOLOIST-WHF | Acute HF |

| Emerging agents | SGLT2-based | Ongoing | Precision therapy |

| Feature | Conventional SGLT2 Inhibitors | Next-Generation SGLT2-Based Agents |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical backbone | C-aryl glucoside | Modified glucoside/hybrid structures |

| Molecular stability | High | Enhanced stability and binding kinetics |

| SGLT2 selectivity | High | Ultra-high or deliberately balanced |

| SGLT1 inhibition | Minimal or absent | Partial (agent-specific) |

| Intestinal effects | Limited | Delayed glucose absorption |

| Incretin activation | Minimal | Increased GLP-1 and GIP secretion |

| Pharmacokinetics | Standard half-life | Optimized exposure and duration |

| Tissue distribution | Predominantly renal | Multi-organ (renal, cardiac, vascular) |

| Glucose-independent effects | Secondary | Prominent and targeted |

| Agent | Transporter Profile | Key Trials | Population | Distinct Clinical Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dapagliflozin | SGLT2 | DAPA-HF, DAPA-CKD | Chronic HF, CKD | Strong chronic cardiorenal protection |

| Empagliflozin | SGLT2 | EMPEROR-Reduced, EMPEROR-Preserved, EMPA-KIDNEY | HF spectrum, CKD | Robust HFpEF evidence |

| Canagliflozin | SGLT2 | CREDENCE | Diabetic CKD | Early renal outcome data |

| Sotagliflozin | SGLT1/SGLT2 | SOLOIST-WHF, SCORED | Recent worsening HF, CKD | Incretin-mediated and acute HF benefits |

| Emerging agents | SGLT2-based | Ongoing | Non-diabetic HF, post-MI | Precision-medicine strategies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Movila, D.; Seiman, D.D.; Dragan, S.R. Next-Generation SGLT2 Inhibitors: Innovations and Clinical Perspectives. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010081

Movila D, Seiman DD, Dragan SR. Next-Generation SGLT2 Inhibitors: Innovations and Clinical Perspectives. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleMovila, Dana, Daniel Duda Seiman, and Simona Ruxanda Dragan. 2026. "Next-Generation SGLT2 Inhibitors: Innovations and Clinical Perspectives" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010081

APA StyleMovila, D., Seiman, D. D., & Dragan, S. R. (2026). Next-Generation SGLT2 Inhibitors: Innovations and Clinical Perspectives. Biomedicines, 14(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010081