RXR Agonist V-125 Induces Distinct Transcriptional and Immunomodulatory Programs in Mammary Tumors of MMTV-Neu Mice Compared to Bexarotene

Abstract

1. Introduction

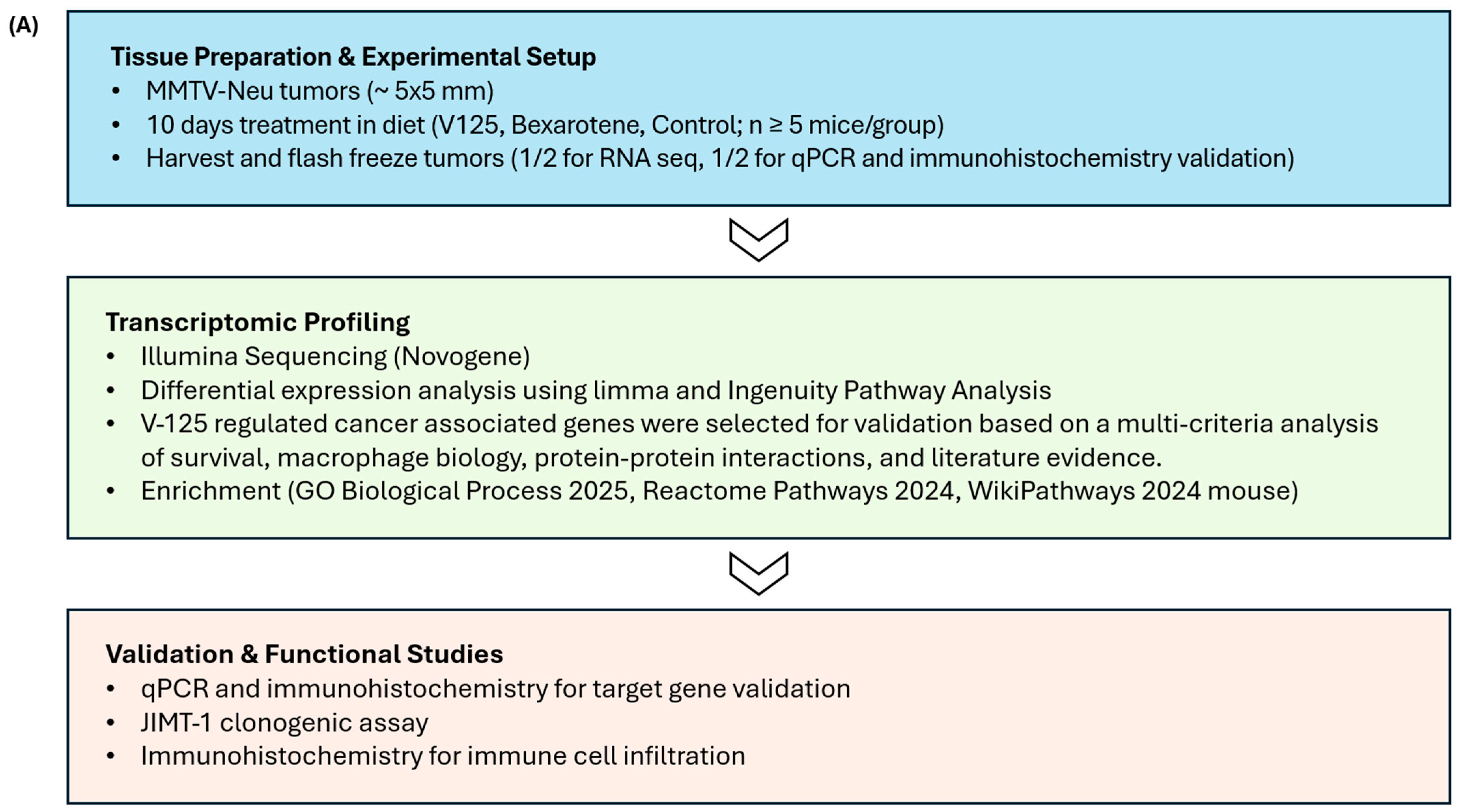

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Drugs

2.3. In Vivo Experiments

2.4. RNA Sequencing

2.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

2.7. Kaplan–Meier Plot Generation

2.8. Colony Formation Assay

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

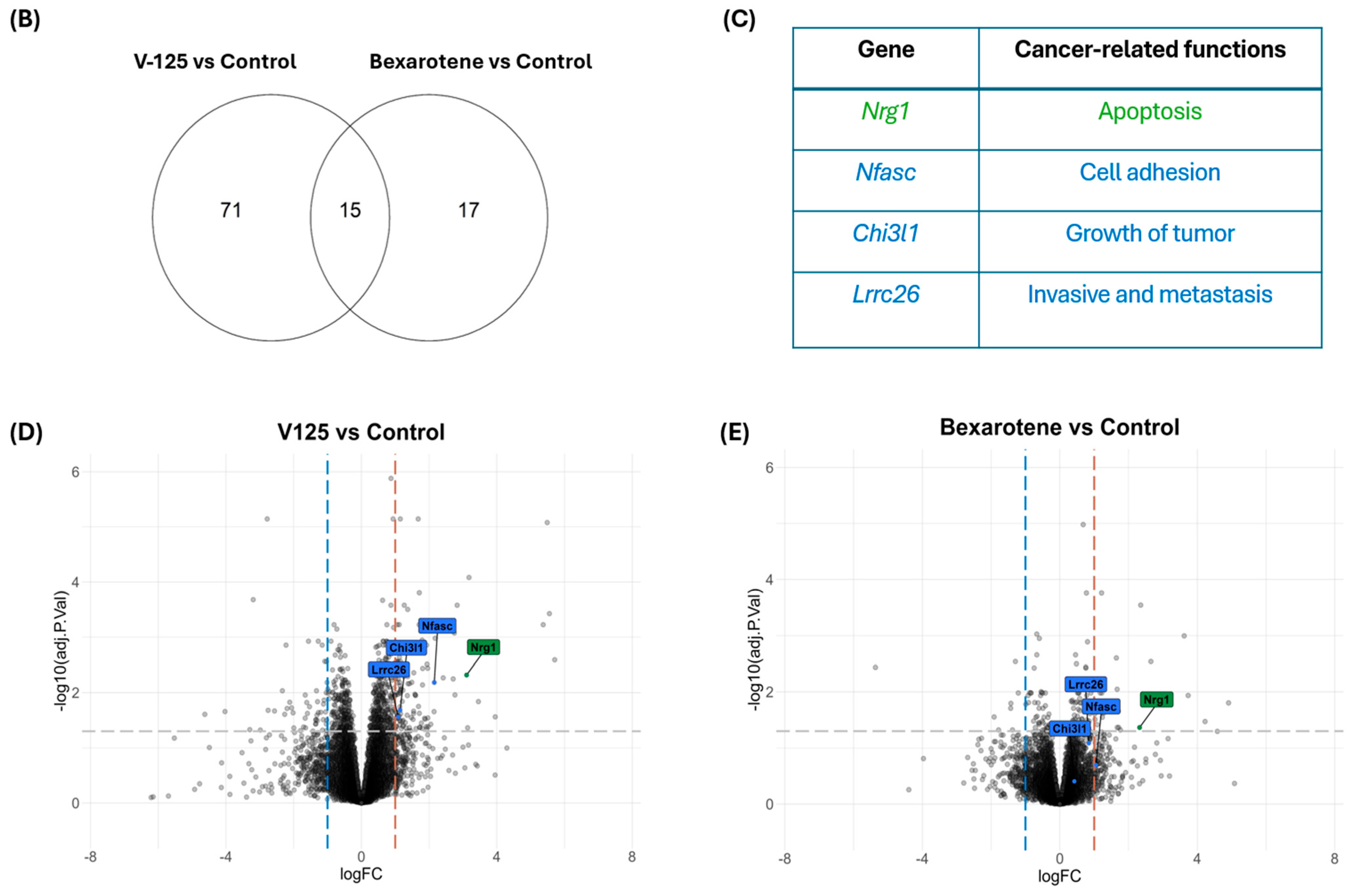

3.1. V-125 and Bexarotene Regulate Overlapping and Distinct Cancer-Associated Gene Sets

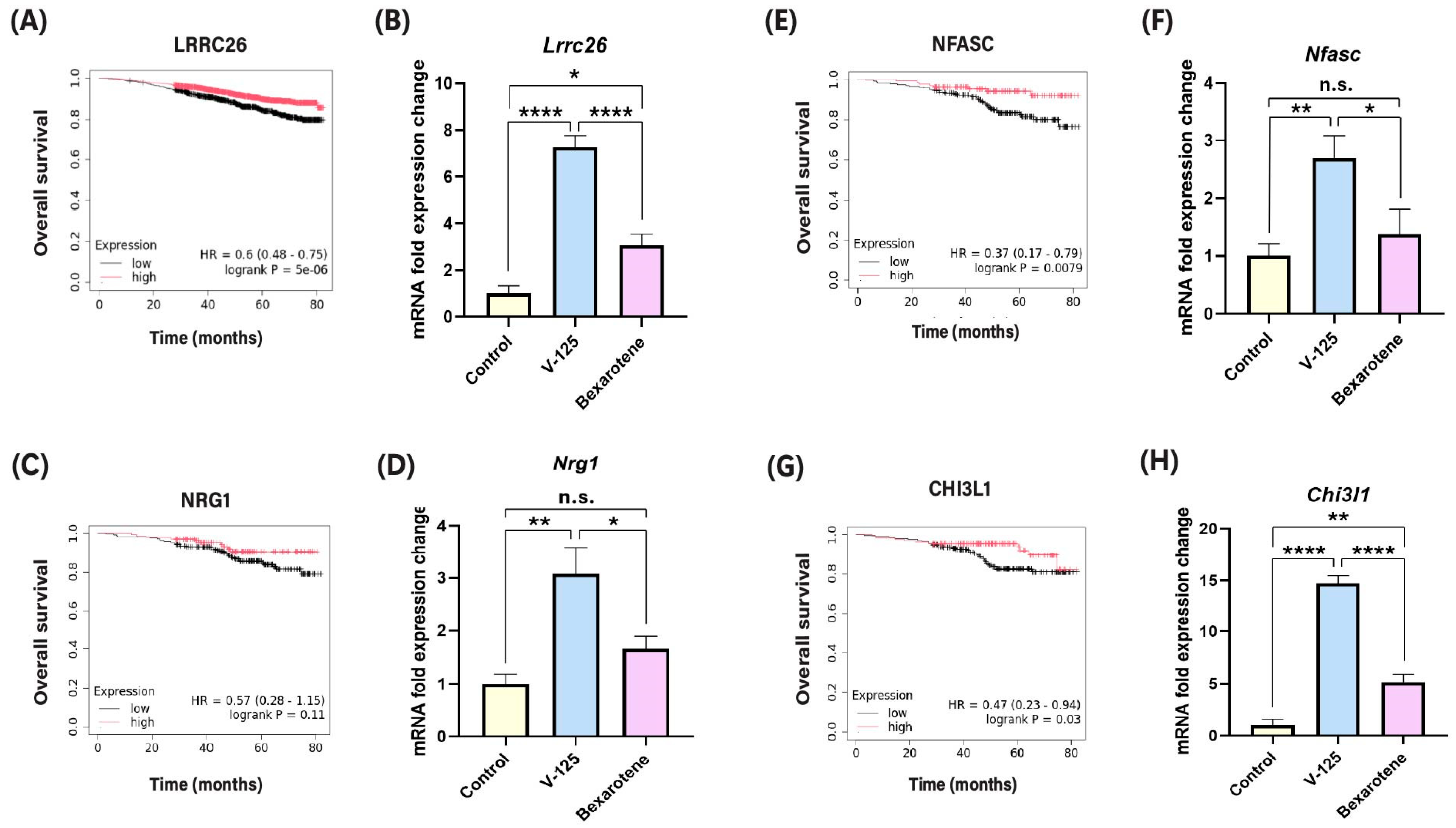

3.2. V-125 Upregulates Genes Associated with Improved Patient Survival

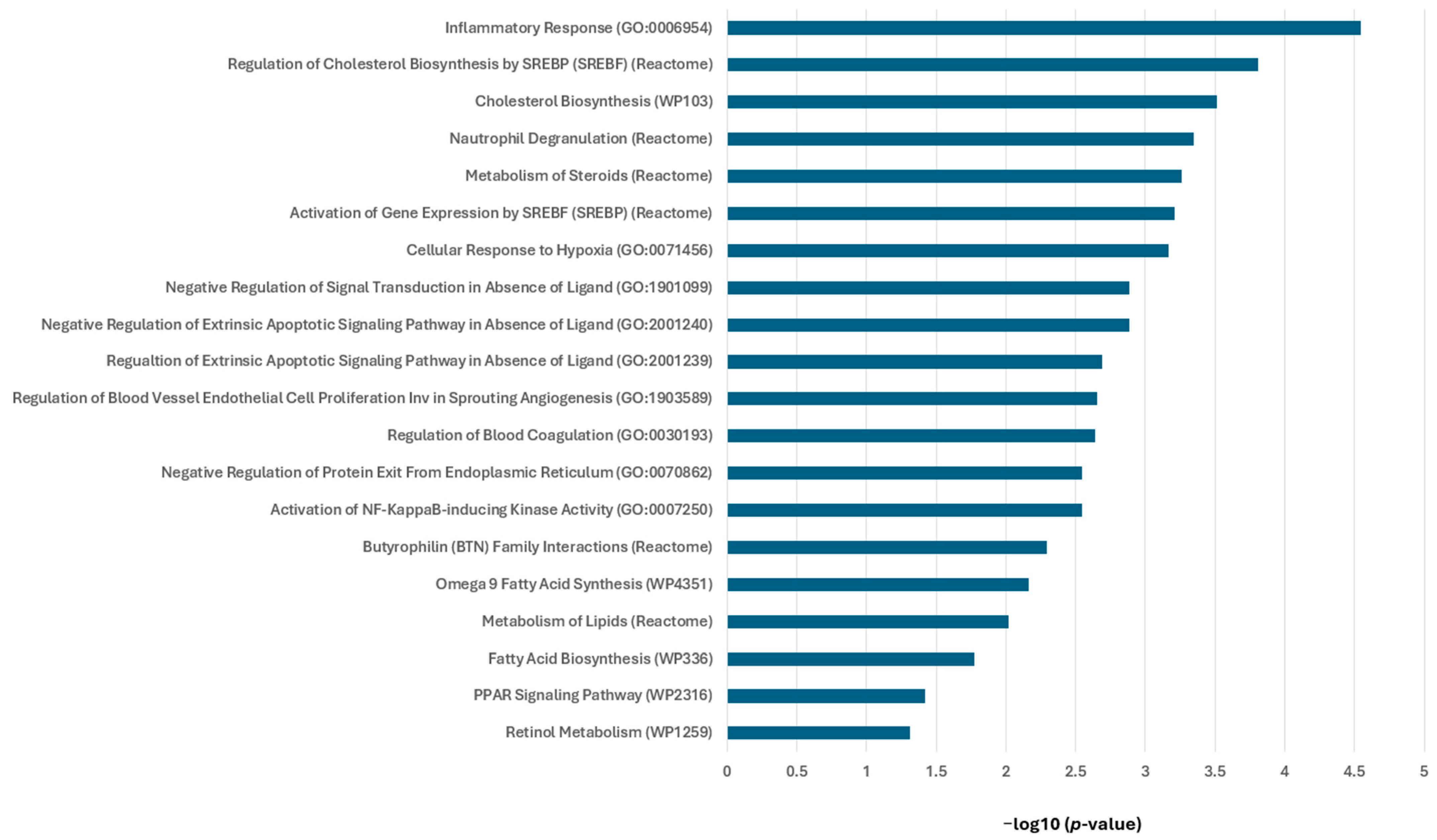

3.3. RXR Agonists Modulate Cancer-Relevant Pathways in MMTV-Neu Mammary Tumors

3.4. Overlapping Function of V-125 and Bexarotene

3.5. V-125 and Bexarotene Enrich for Distinct Pathways in MMTV-Neu Mammary Tumors

3.6. V-125 Promotes an Anti-Tumor Immune Microenvironment

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RXR | Retinoid X receptor |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| RAR | Retinoic Acid Receptor |

| LXR | Liver X Receptor |

| MMTV | Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophages |

| qPCR | quantitative PCR |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| IPA | Ingenuity Pathway Analysis |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| KM Plotter | Kaplan–Meier Plotter |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| NIK | NF-κB-Inducing Kinase |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

References

- Dhiman, V.K.; Bolt, M.J.; White, K.P. Nuclear receptors in cancer—Uncovering new and evolving roles through genomic analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szanto, A.; Narkar, V.; Shen, Q.; Uray, I.P.; Davies, P.J.; Nagy, L. Retinoid X receptors: X-ploring their (patho)physiological functions. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11, S126–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefebvre, P.; Benomar, Y.; Staels, B. Retinoid X receptors: Common heterodimerization partners with distinct functions. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Evans, R.M. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell 1995, 83, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germain, P.; Staels, B.; Dacquet, C.; Spedding, M.; Laudet, V. Overview of nomenclature of nuclear receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, H.S.; Szanto, A.; Nagy, L.; Davies, P.J. The retinoid X receptor and its ligands: Versatile regulators of metabolic function, cell differentiation and cell death. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2003, 17, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Altucci, L.; Leibowitz, M.D.; Ogilvie, K.M.; de Lera, A.R.; Gronemeyer, H. RAR and RXR modulation in cancer and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schierle, S.; Merk, D. Therapeutic modulation of retinoid X receptors—SAR and therapeutic potential of RXR ligands and recent patents. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2019, 29, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zati Zehni, A.; Batz, F.; Cavaillès, V.; Sixou, S.; Kaltofen, T.; Keckstein, S.; Heidegger, H.H.; Ditsch, N.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; et al. Cytoplasmic Localization of RXRα Determines Outcome in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattori, J.; Campos, J.L.; Doratioto, T.R.; Assis, L.M.; Vitorino, M.T.; Polikarpov, I.; Xavier-Neto, J.; Figueira, A.C. RXR agonist modulates TR: Corepressor dissociation upon 9-cis retinoic acid treatment. Mol Endocrinol. 2015, 29, 258–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.M.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Nuclear Receptors, RXR, and the Big Bang. Cell 2014, 157, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, P.; Duan, X.; Huang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhu, J.; Guo, H.; Tian, H.; Zou, C.G.; Xie, K. Nuclear receptors in health and disease: Signaling pathways, biological functions and pharmaceutical interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, L.; Szanto, A.; Szatmari, I.; Széles, L. Nuclear hormone receptors enable macrophages and dendritic cells to sense their lipid environment and shape their immune response. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 739–789, Erratum in: Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, L.M.; Teixeira, F.M.E.; Sato, M.N. Impact of Retinoic Acid on Immune Cells and Inflammatory Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 3067126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rőszer, T.; Menéndez-Gutiérrez, M.P.; Cedenilla, M.; Ricote, M. Retinoid X receptors in macrophage biology. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 24, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, A.S.; Hung, P.Y.; Chowdhury, A.S.; Liby, K.T. Retinoid X Receptor agonists as selective modulators of the immune system for the treatment of cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 252, 108561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moerland, J.A.; Zhang, D.; Reich, L.A.; Carapellucci, S.; Lockwood, B.; Leal, A.S.; Krieger-Burke, T.; Aleiwi, B.; Ellsworth, E.; Liby, K.T. The novel rexinoid MSU-42011 is effective for the treatment of preclinical Kras-driven lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Leal, A.S.; Carapellucci, S.; Shahani, P.H.; Bhogal, J.S.; Ibrahim, S.; Raban, S.; Jurutka, P.W.; Marshall, P.A.; Sporn, M.B.; et al. Testing Novel Pyrimidinyl Rexinoids: A New Paradigm for Evaluating Rexinoids for Cancer Prevention. Cancer Prev. Res. 2019, 12, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Querfeld, C.; Nagelli, L.V.; Rosen, S.T.; Kuzel, T.M.; Guitart, J. Bexarotene in the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2006, 7, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragnev, K.H.; Petty, W.J.; Shah, S.J.; Lewis, L.D.; Black, C.C.; Memoli, V.; Nugent, W.C.; Hermann, T.; Negro-Vilar, A.; Rigas, J.R.; et al. A proof-of-principle clinical trial of bexarotene in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 1794–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteva, F.J.; Glaspy, J.; Baidas, S.; Laufman, L.; Hutchins, L.; Dickler, M.; Tripathy, D.; Cohen, R.; DeMichele, A.; Yocum, R.C.; et al. Multicenter phase II study of oral bexarotene for patients with metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, P. Bexarotene in combination with chemotherapy fails to prolong survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from the SPIRIT I and II trials. Clin. Lung Cancer 2005, 7, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, O.D.; Welch, J.S. Retinoic Acid Receptors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Therapy. Cancers 2019, 11, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, L.A.; Leal, A.S.; Ellsworth, E.; Liby, K.T. The Novel RXR Agonist MSU-42011 Differentially Regulates Gene Expression in Mammary Tumors of MMTV-Neu Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uray, I.P.; Dmitrovsky, E.; Brown, P.H. Retinoids and rexinoids in cancer prevention: From laboratory to clinic. Semin. Oncol. 2016, 43, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, P.J.; Berry, S.A.; Shipley, G.L.; Eckel, R.H.; Hennuyer, N.; Crombie, D.L.; Ogilvie, K.M.; Peinado-Onsurbe, J.; Fievet, C.; Leibowitz, M.D.; et al. Metabolic effects of rexinoids: Tissue-specific regulation of lipoprotein lipase activity. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001, 59, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, L.M. Retinoids and their receptors in differentiation, embryogenesis, and neoplasia. FASEB J. 1991, 5, 2924–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouamrane, L.; Larrieu, G.; Gauthier, B.; Pineau, T. RXR activators molecular signalling: Involvement of a PPAR alpha-dependent pathway in the liver and kidney, evidence for an alternative pathway in the heart. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 138, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, A.S.; Zydeck, K.; Carapellucci, S.; Reich, L.A.; Zhang, D.; Moerland, J.A.; Sporn, M.B.; Liby, K.T. Retinoid X receptor agonist LG100268 modulates the immune microenvironment in preclinical breast cancer models. Npj Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiss, M.; Czimmerer, Z.; Nagy, G.; Bieniasz-Krzywiec, P.; Ehling, M.; Pap, A.; Poliska, S.; Boto, P.; Tzerpos, P.; Horvath, A.; et al. Retinoid X receptor suppresses a metastasis-promoting transcriptional program in myeloid cells via a ligand-insensitive mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10725–10730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova-Acebes, M.; Menéndez-Gutiérrez, M.P.; Porcuna, J.; Álvarez-Errico, D.; Lavin, Y.; García, A.; Kobayashi, S.; Le Berichel, J.; Núñez, V.; Were, F.; et al. RXRs control serous macrophage neonatal expansion and identity and contribute to ovarian cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leal, A.S.; Moerland, J.A.; Zhang, D.; Carapellucci, S.; Lockwood, B.; Krieger-Burke, T.; Aleiwi, B.; Ellsworth, E.; Liby, K.T. The RXR Agonist MSU42011 Is Effective for the Treatment of Preclinical HER2+ Breast Cancer and Kras-Driven Lung Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, N.B.; Lü, M.H.; Fan, Y.H.; Cao, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.R.; Yang, S.M. Macrophages in tumor microenvironments and the progression of tumors. J. Immunol. Res. 2012, 2012, 948098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bied, M.; Ho, W.W.; Ginhoux, F.; Blériot, C. Roles of macrophages in tumor development: A spatiotemporal perspective. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 20, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guan, X.; Wei, J.; Yuan, B.; He, S.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; et al. The role of macrophages during breast cancer development and response to chemotherapy. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 22, 1938–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrou, M.; Constantinidou, A. Tumor associated macrophages in breast cancer progression: Implications and clinical relevance. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1441820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpott, J.; Kazimierczyk, S.; Korgaonkar, P.; Bordt, E.; Zois, J.; Vasudevan, C.; Meng, D.; Bhatia, I.; Lu, N.; Jimena, B.; et al. RXRα Regulates the Development of Resident Tissue Macrophages. Immunohorizons 2022, 6, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, L.A.; Moerland, J.A.; Leal, A.S.; Zhang, D.; Carapellucci, S.; Lockwood, B.; Jurutka, P.W.; Marshall, P.A.; Wagner, C.E.; Liby, K.T. The rexinoid V-125 reduces tumor growth in preclinical models of breast and lung cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, L.S.; Wells, R.A. Cross-Talk between PPARs and the Partners of RXR: A Molecular Perspective. PPAR Res. 2009, 2009, 925309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, J.F.; Freedman, L.P. Nuclear receptors as drug targets in metabolic diseases: New approaches to therapy. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 17, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, M.; Kapanen, A.I.; Junttila, T.; Raheem, O.; Grenman, S.; Elo, J.; Elenius, K.; Isola, J. Characterization of a novel cell line established from a patient with Herceptin-resistant breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2004, 3, 1585–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurutka, P.W.; di Martino, O.; Reshi, S.; Mallick, S.; Sabir, Z.L.; Staniszewski, L.J.P.; Warda, A.; Maiorella, E.L.; Minasian, A.; Davidson, J.; et al. Modeling, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Potential Retinoid-X-Receptor (RXR) Selective Agonists: Analogs of 4-[1-(3,5,5,8,8-Pentamethyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahyro-2-naphthyl)ethynyl]benzoic Acid (Bexarotene) and 6-(Ethyl(4-isobutoxy-3-isopropylphenyl)amino)nicotinic Acid (NEt-4IB). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, C.T.; Webster, M.A.; Schaller, M.; Parsons, T.J.; Cardiff, R.D.; Muller, W.J. Expression of the neu protooncogene in the mammary epithelium of transgenic mice induces metastatic disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10578–10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Rennhack, J.; Andrechek, E.R.; Rockwell, C.E.; Liby, K.T. Identification of an Unfavorable Immune Signature in Advanced Lung Tumors from Nrf2-Deficient Mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 1535–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuleshov, M.V.; Jones, M.R.; Rouillard, A.D.; Fernandez, N.F.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Koplev, S.; Jenkins, S.L.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Lachmann, A.; et al. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W90–W97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J., Jr.; Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lánczky, A.; Győrffy, B. Web-Based Survival Analysis Tool Tailored for Medical Research (KMplot): Development and Implementation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Fu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Cohen, D.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, B.; Liu, X.S. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W509–W514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D457–D462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, A.; Balcı, H.; Hanspers, K.; Coort, S.L.; Martens, M.; Slenter, D.N.; Ehrhart, F.; Digles, D.; Waagmeester, A.; Wassink, I.; et al. WikiPathways 2024: Next generation pathway database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 52, D679–D689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croft, D.; O’Kelly, G.; Wu, G.; Haw, R.; Gillespie, M.; Matthews, L.; Caudy, M.; Garapati, P.; Gopinath, G.; Jassal, B.; et al. Reactome: A database of reactions, pathways and biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D691–D697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheban, B.A.; Colosi, H.A.; Gheban-Roșca, I.A.; Georgiu, C.; Gheban, D.; Crişan, D.; Crişan, M. Techniques for digital histological morphometry of the pineal gland. Acta Histochem. 2022, 124, 151897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, A.R.; Yue, W. Semi-quantitative Determination of Protein Expression using Immunohistochemistry Staining and Analysis: An Integrated Protocol. Bio-Protocol 2019, 9, e3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyer, C.L.; Lanier, A.; Qian, J.; Coleman, D.; Hill, J.; Vuligonda, V.; Sanders, M.E.; Mazumdar, A.; Brown, P.H. IRX4204 Induces Senescence and Cell Death in HER2-positive Breast Cancer and Synergizes with Anti-HER2 Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 2558–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.R.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.J.; Xi, M.J.; Xia, B.H.; Deng, K.; Yang, J.L. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment: From mechanisms to therapeutics. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, S.; Shi, Y.; Yin, B. Macrophage barrier in the tumor microenvironment and potential clinical applications. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Miao, Y.Q.; Suo, L.P.; Wang, X.; Mao, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhou, N.; Tian, J.R.; Yu, X.Y.; Wang, T.X.; et al. CD206 modulates the role of M2 macrophages in the origin of metastatic tumors. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 1462–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhosle, V.K.; Sun, C.; Patel, S.; Ho, T.W.W.; Westman, J.; Ammendolia, D.A.; Langari, F.M.; Fine, N.; Toepfner, N.; Li, Z.; et al. The chemorepellent, SLIT2, bolsters innate immunity against Staphylococcus aureus. Elife 2023, 12, e87392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Huang, L.; Ding, Y.; Sherchan, P.; Peng, W.; Zhang, J.H. Recombinant Slit2 suppresses neuroinflammation and Cdc42-mediated brain infiltration of peripheral immune cells via Robo1-srGAP1 pathway in a rat model of germinal matrix hemorrhage. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brtko, J.; Dvorak, Z. Natural and synthetic retinoid X receptor ligands and their role in selected nuclear receptor action. Biochimie 2020, 179, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, M.I.; Xia, Z. The retinoid X receptors and their ligands. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2012, 1821, 21–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojetin, D.J.; Matta-Camacho, E.; Hughes, T.S.; Srinivasan, S.; Nwachukwu, J.C.; Cavett, V.; Nowak, J.; Chalmers, M.J.; Marciano, D.P.; Kamenecka, T.M.; et al. Structural mechanism for signal transduction in RXR nuclear receptor heterodimers. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhao, B.; Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Guo, R.; Xin, D.; Yue, B.; Wang, F. NRG1 fusion glycoproteins in cancer progression—Structural mechanisms and therapeutic potential: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 323, 147057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Mishra, S.; Xu, W.; Thompson, W.E.; Chowdhury, I. Neuregulin-1 signaling regulates cytokines and chemokines expression and secretion in granulosa cell. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yun, J.H.; Hong, Y.; Hong, M.H.; Kim, G.; Lee, J.S.; Woo, R.S.; Lee, J.; Yang, E.J.; Kim, I.S. Anti-inflammatory effects of neuregulin-1 in HaCaT keratinocytes and atopic dermatitis-like mice stimulated with Der p 38. Cytokine 2024, 174, 156439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Choi, J.H.; Hong, M.H.; Kim, G.; Lee, J.S.; Woo, R.S.; Yang, E.J.; Kim, I.S. Neuregulin-1 suppresses anti-apoptotic effect of Der p 38 on neutrophils by inhibition of cytokine secretion. Mol. Cell. Toxicol. 2023, 19, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libreros, S.; Iragavarapu-Charyulu, V. YKL-40/CHI3L1 drives inflammation on the road of tumor progression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 98, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.E.; Yeo, I.J.; Han, S.B.; Yun, J.; Kim, B.; Yong, Y.J.; Lim, Y.S.; Kim, T.H.; Son, D.J.; Hong, J.T. Significance of chitinase-3-like protein 1 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases and cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Meng, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Qin, X. Uncovering novel mechanisms of chitinase-3-like protein 1 in driving inflammation-associated cancers. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, M.; Zhou, X.; Sohn, J.H.; Zhu, L.; Jie, Z.; Yang, J.Y.; Zheng, X.; Xie, X.; Yang, J.; Shi, Y.; et al. NF-κB-inducing kinase maintains T cell metabolic fitness in antitumor immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 193–204, Erratum in: Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, W.; Augustine, D.; Rao, R.S.; Patil, S.; Awan, K.H.; Sowmya, S.V.; Haragannavar, V.C.; Prasad, K. Lipid metabolism in cancer: A systematic review. J. Carcinog. 2021, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Perez, M.; Urdiroz-Urricelqui, U.; Bigas, C.; Benitah, S.A. The role of lipids in cancer progression and metastasis. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 1675–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.; Pan, S.; Shan, B.; Diao, H.; Jin, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Han, S.; Liu, W.; He, J.; et al. Lipid metabolic reprograming: The unsung hero in breast cancer progression and tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Yu, W.; Li, P.; Ou, D.; Liu, J.; Ma, H.; Sun, Q.; Liang, A.; Huang, C.; et al. PPARγ phase separates with RXRα at PPREs to regulate target gene expression. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, R.; Strasser, J.; Jow, L.; Hoener, P.; Paterniti, J.R., Jr.; Heyman, R.A. RXR agonists activate PPARalpha-inducible genes, lower triglycerides, and raise HDL levels in vivo. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Ide, T.; Shimano, H.; Yahagi, N.; Amemiya-Kudo, M.; Matsuzaka, T.; Yatoh, S.; Kitamine, T.; Okazaki, H.; Tamura, Y.; et al. Cross-talk between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) alpha and liver X receptor (LXR) in nutritional regulation of fatty acid metabolism. I. PPARs suppress sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c promoter through inhibition of LXR signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003, 17, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.C.; Glass, C.K. PPAR- and LXR-dependent pathways controlling lipid metabolism and the development of atherosclerosis. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 2161–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tontonoz, P. Liver X receptors in lipid signalling and membrane homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo-Umeda, K.; Makishima, M. Exploring the Roles of Liver X Receptors in Lipid Metabolism and Immunity in Atherosclerosis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modak, M.; Mattes, A.K.; Reiss, D.; Skronska-Wasek, W.; Langlois, R.; Sabarth, N.; Konopitzky, R.; Ramirez, F.; Lehr, K.; Mayr, T.; et al. CD206+ tumor-associated macrophages cross-present tumor antigen and drive antitumor immunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 7, e155022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A.; Hu, K.H.; Kersten, K.; Courau, T.; Kuhn, N.F.; Zaleta-Linares, I.; Samad, B.; Combes, A.J.; Krummel, M.F. Critical role of CD206+ macrophages in promoting a cDC1-NK-CD8 T cell anti-tumor immune axis. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, e20240957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanita, K.; Fujimura, T.; Sato, Y.; Lyu, C.; Kambayashi, Y.; Ogata, D.; Fukushima, S.; Miyashita, A.; Nakajima, H.; Nakamura, M.; et al. Bexarotene Reduces Production of CCL22 From Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrtic, M.; Yusuf, B.; Patel, S.; Reddy, E.C.; Ting, K.K.Y.; Cybulsky, M.I.; Freeman, S.A.; Robinson, L.A. The neurorepellent SLIT2 inhibits LPS-induced proinflammatory signaling in macrophages. J. Immunol. 2025, 214, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahirwar, D.K.; Charan, M.; Mishra, S.; Verma, A.K.; Shilo, K.; Ramaswamy, B.; Ganju, R.K. Slit2 Inhibits Breast Cancer Metastasis by Activating M1-Like Phagocytic and Antifibrotic Macrophages. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 5255–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuthu, S.; Chauhan, Y.D.; Mirza, A.A.; Saad, M.Z.; Bittla, P.; Paidimarri, S.P.; Nath, T.S. Role of Retinoids and Their Analogs in the Treatment of Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e69318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragnev, K.H.; Whyman, J.D.; Hahn, C.K.; Kebbekus, P.E.; Kokko, S.F.; Bhatt, S.M.; Rigas, J.R. A phase I/II study of bexarotene with carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel for the treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 5531–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nrg1 | (F): 5′-TCCGGCAGAGCCTTCGGTCA-3′ |

| (R): 5′-TCTCCCGTAGCCTCGGTGGC-3′ | |

| Nfasc | (F): 5′-TGACCTGGCTGAGAGGAGTGTG-3′ |

| (R): 5′-AACCTGGAGTGGTCATGCCACA-3′ | |

| Slit2 | (F): 5′-CCATGTAAAAATGATGGCACCTG-3′ |

| (R): 5′-GTGTTGCGGGGGATATTCCT-3′ | |

| Chi3l1 | (F): 5′-GTACAAGCTGGTCTGCTACT-3′ |

| (R): 5′-GTTGGAGGCAATCTCGGAAA-3′ | |

| Lrrc26 | (F): 5′-TTGCACTTGGCTGCGTAAGCAC-3′ |

| (R): 5′-CGGAAAAGCTGTCAGTAGGCTG-3′ | |

| Gapdh | (F): 5′-CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG-3′ |

| (R): 5′-ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG-3′ | |

| ABCA1 | (F): 5′-CAGGCTACTACCTGACCTTGGT-3′ |

| (R): 5′-CTGCTCTGAGAAACACTGTCCTC-3′ | |

| SREBP | (F): 5′-ACTTCTGGAGGCATCGCAAGCA-3′ |

| (R): 5′-AGGTTCCAGAGGAGGCTACAAG-3′ | |

| GAPDH | (F): 5′-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3′ |

| (R): 5′-ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chowdhury, A.S.; Reich, L.A.; Liby, K.T.; Yeh, E.S.; Leal, A.S. RXR Agonist V-125 Induces Distinct Transcriptional and Immunomodulatory Programs in Mammary Tumors of MMTV-Neu Mice Compared to Bexarotene. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010080

Chowdhury AS, Reich LA, Liby KT, Yeh ES, Leal AS. RXR Agonist V-125 Induces Distinct Transcriptional and Immunomodulatory Programs in Mammary Tumors of MMTV-Neu Mice Compared to Bexarotene. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleChowdhury, Afrin Sultana, Lyndsey A. Reich, Karen T. Liby, Elizabeth S. Yeh, and Ana S. Leal. 2026. "RXR Agonist V-125 Induces Distinct Transcriptional and Immunomodulatory Programs in Mammary Tumors of MMTV-Neu Mice Compared to Bexarotene" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010080

APA StyleChowdhury, A. S., Reich, L. A., Liby, K. T., Yeh, E. S., & Leal, A. S. (2026). RXR Agonist V-125 Induces Distinct Transcriptional and Immunomodulatory Programs in Mammary Tumors of MMTV-Neu Mice Compared to Bexarotene. Biomedicines, 14(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010080