Cinnamomum cassia Modulates Key Players of Gut–Liver Axis in Murine Lupus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Animals and Study Groups

2.3. Extraction and Purification of Total DNA from Feces

2.4. High-Throughput Sequencing of Bacterial 16S rRNA Gene

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.6. Western Blot and Antibody Array

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Gut Microbiota

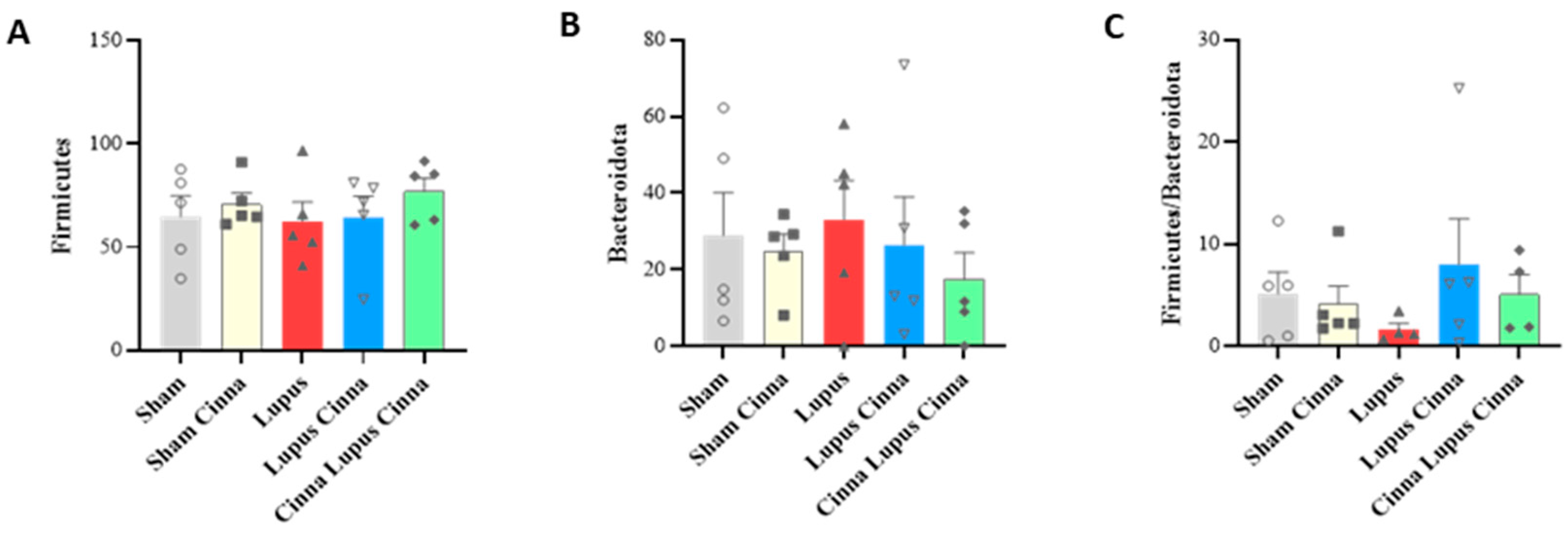

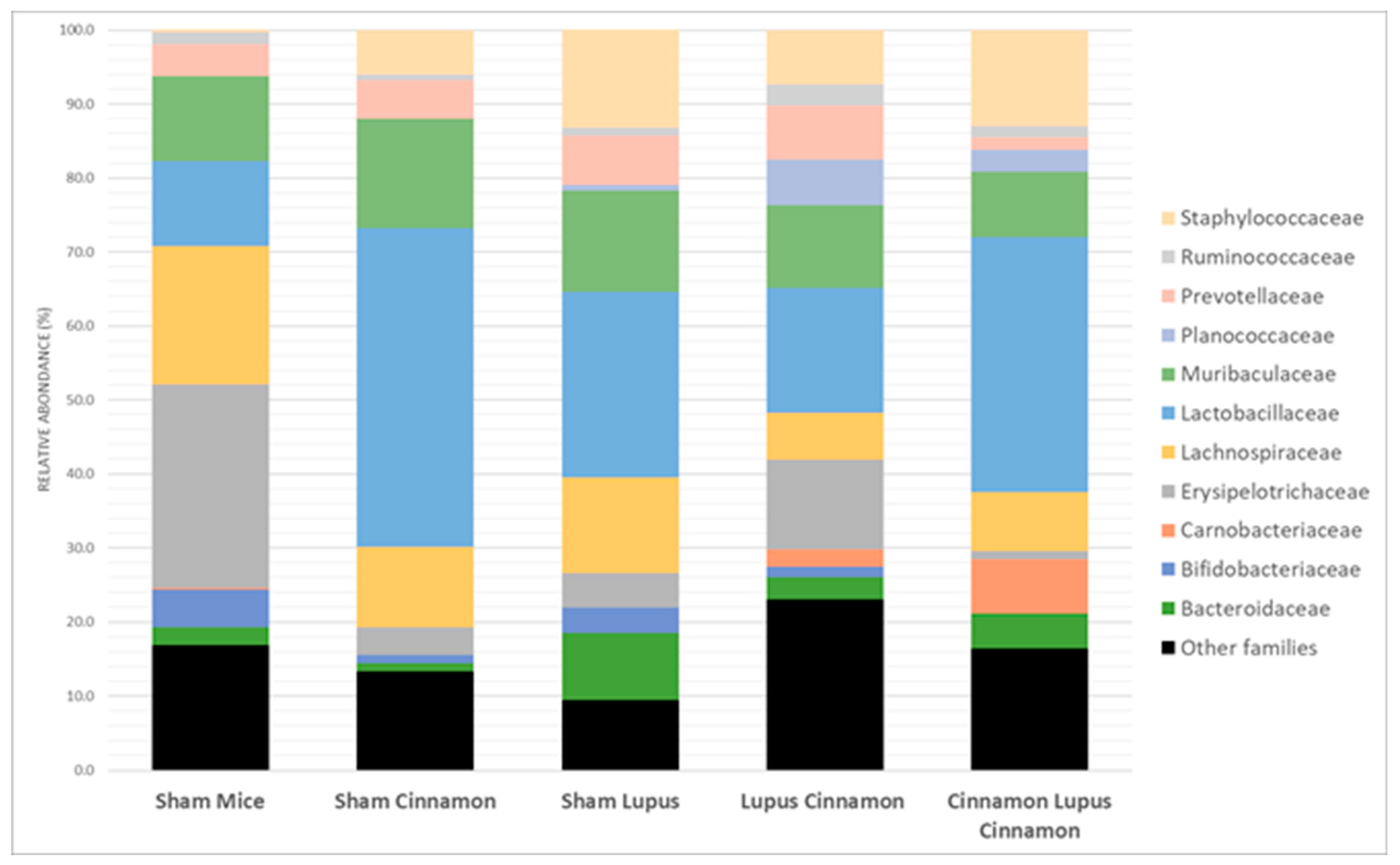

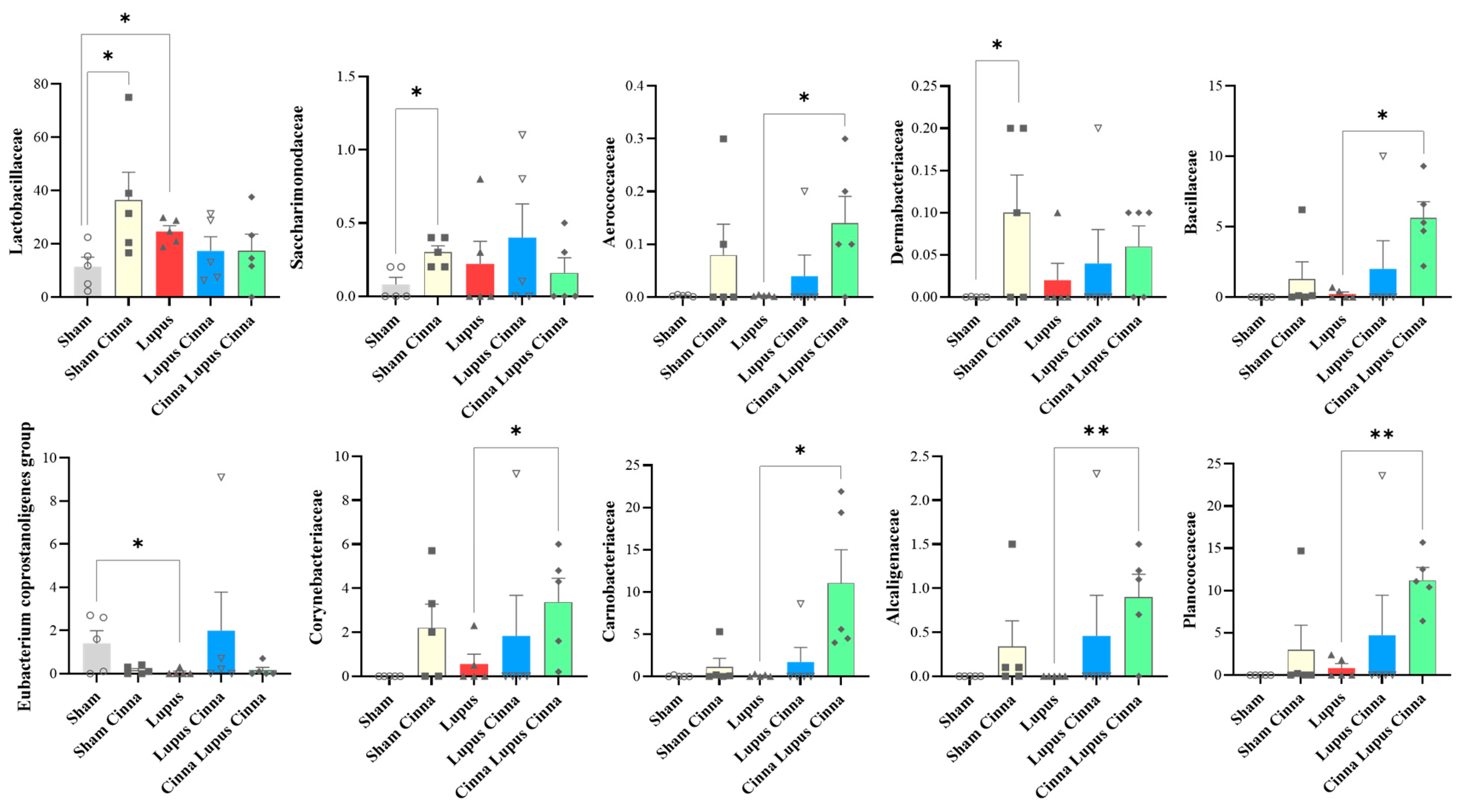

3.2. Effect of Lupus and Cinnamon on Microbial Diversity

3.3. Effect of Lupus and Cinnamon on Microbial Communities

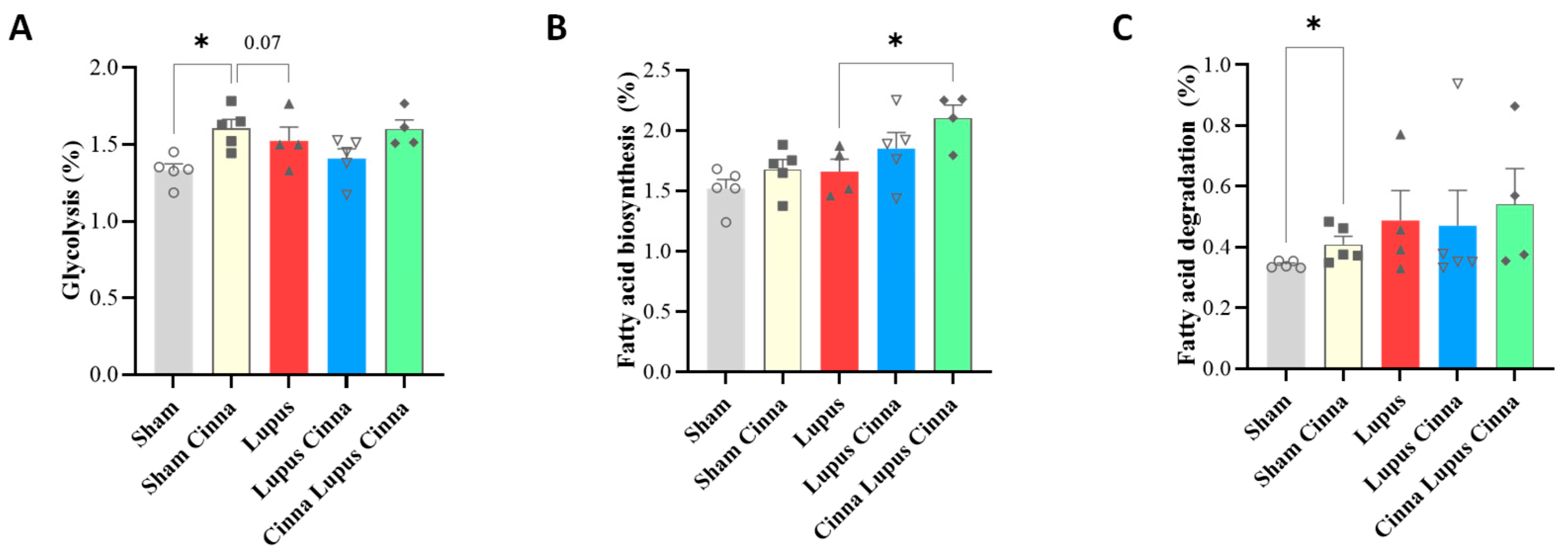

3.4. KEGG Bioinformatic Analysis

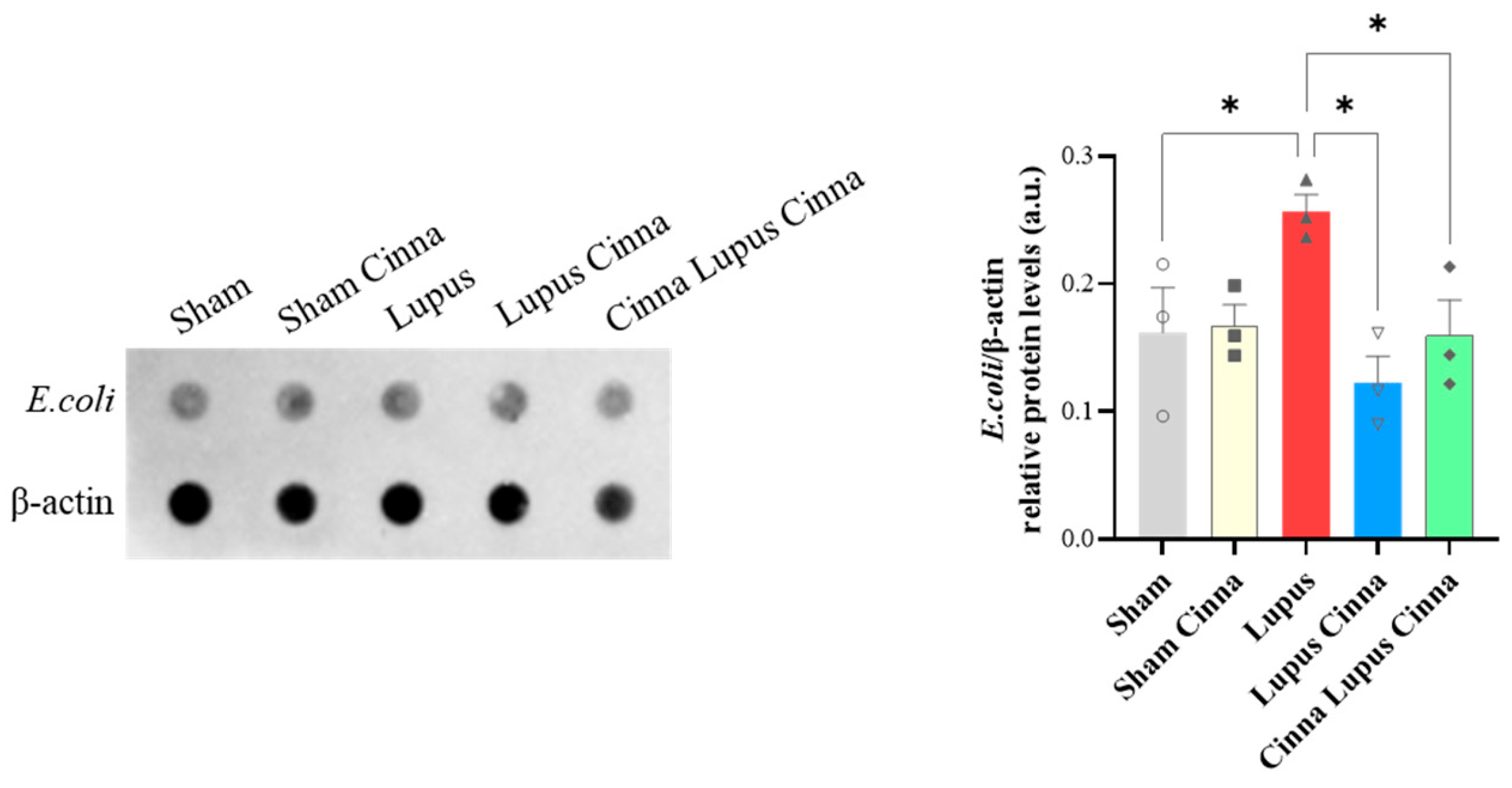

3.5. Escherichia coli Protein Expression in Liver Tissue

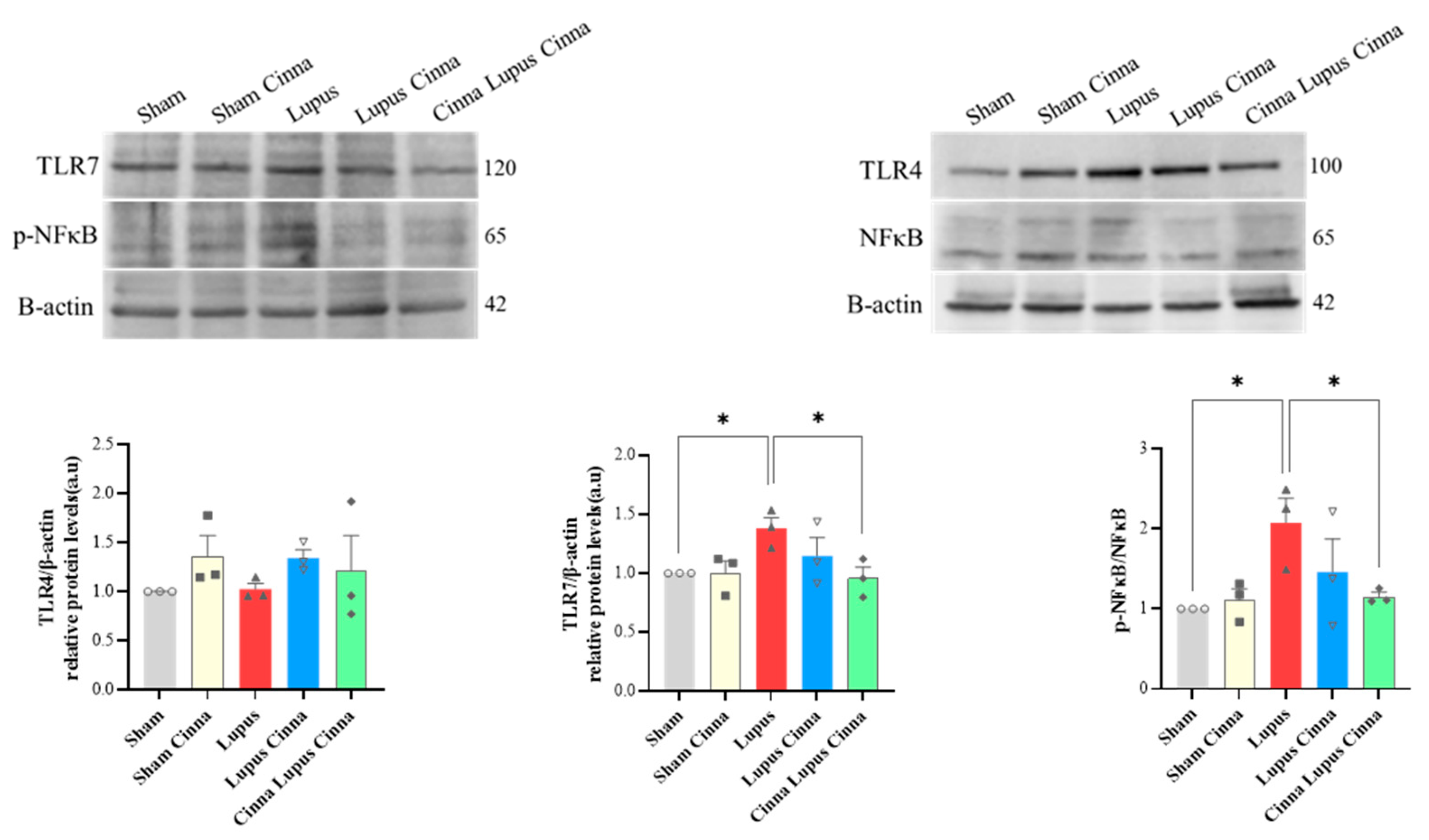

3.6. TLR-4, TLR-7, and NFκB in the Liver

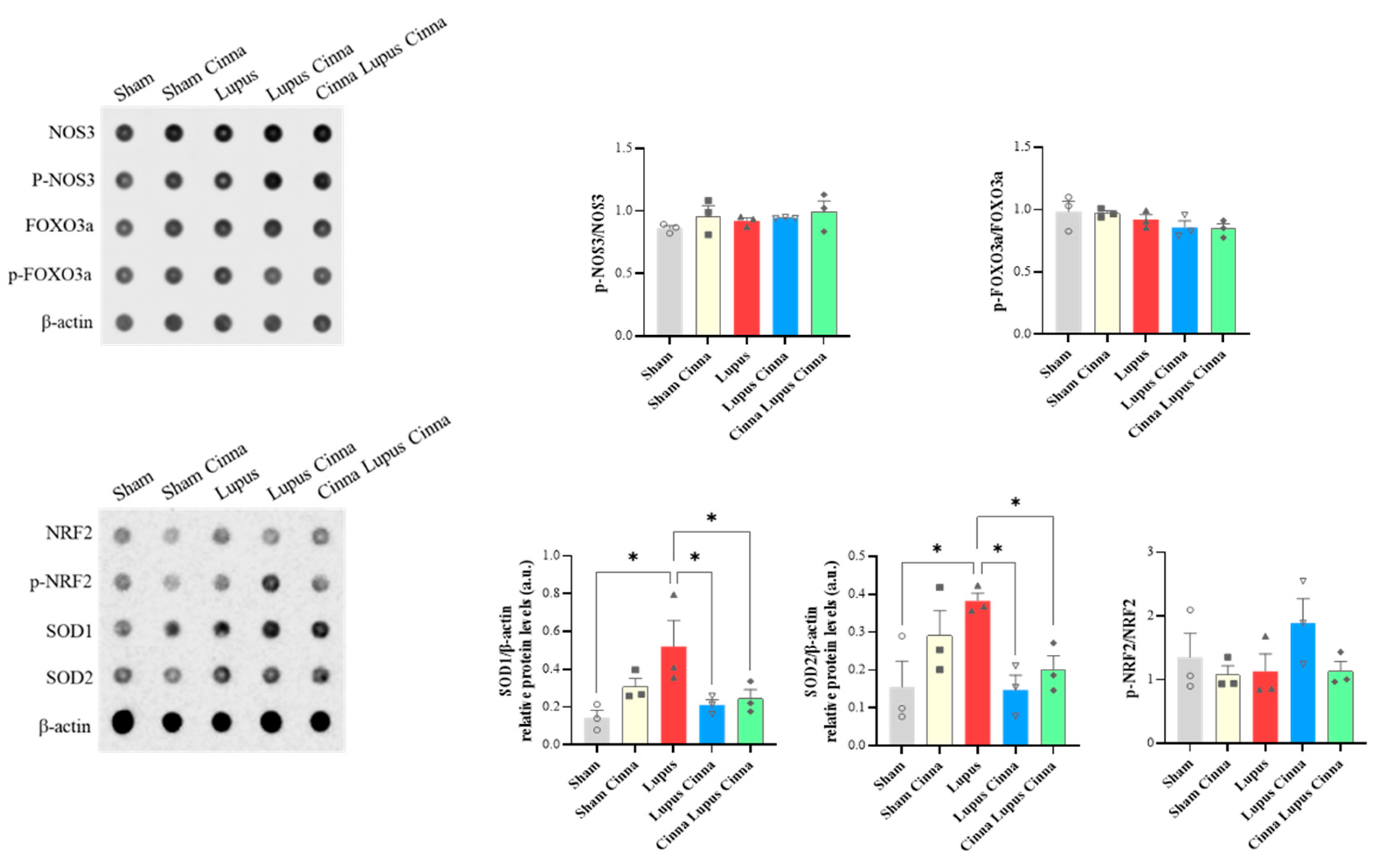

3.7. Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis Markers in the Liver

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnaud, L.; Chasset, F.; Martin, T. Immunopathogenesis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Update. Autoimmun. Rev. 2024, 23, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouly, G.; Hajal, J.; Noujeim, C.; Choueiry, M.; Nassereddine, H.; Smayra, V.; Saliba, Y.; Fares, N. New Insights in Gut-Liver Axis in Wild-Type Murine Imiquimod-Induced Lupus. Lupus 2021, 30, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Littman, D.R. The Microbiome in Infectious Disease and Inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 759–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manos, J. The Human Microbiome in Disease and Pathology. Apmis 2022, 130, 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, K.; Xie, Y.; Wang, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, T. Gut Microbiota: A Newly Identified Environmental Factor in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1202850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Ji, J.; Li, N.; Yin, Z.; Fan, G. Integrated Metabolomics and Gut Microbiome Analysis Reveals the Efficacy of a Phytochemical Constituent in the Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2024, 68, e2200578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouly, G.; Martin, C.-M.-A.; Baz, Y.; Saliba, Y.; Baramili, A.-M.; Fares, N. Antioxidant and Anti-Apoptotic Neuroprotective Effects of Cinnamon in Imiquimod-Induced Lupus. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokogawa, M.; Takaishi, M.; Nakajima, K.; Kamijima, R.; Fujimoto, C.; Kataoka, S.; Terada, Y.; Sano, S. Epicutaneous Application of Toll-like Receptor 7 Agonists Leads to Systemic Autoimmunity in Wild-Type Mice: A New Model of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.-O.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, I.S.; Kim, W.-I.; Lee, S.-J.; Pak, S.-W.; Shin, I.-S.; Kim, T. Cinnamomum cassia (L.) J.Presl Alleviates Allergic Responses in Asthmatic Mice via Suppression of MAPKs and MMP-9. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 906916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazmand, S.; Mirzaei, M.; Hosseinian, S.; Khazdair, M.R.; Gowhari Shabgah, A.; Baghcheghi, Y.; Hedayati-Moghadam, M. The Effect of Cinnamomum cassia Extract on Oxidative Stress in the Liver and Kidney of STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2022, 19, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouly, G.; Saliba, Y.; Hajal, J.; Zein-El-Din, A.; Fakhoury, L.; Najem, R.; Smayra, V.; Nassereddine, H.; Fares, N. Cinnamomum cassia Alleviates Neuropsychiatric Lupus in a Murine Experimental Model. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltz, R.M.; Keirsey, J.; Kim, S.C.; Mackos, A.R.; Gharaibeh, R.Z.; Moore, C.C.; Xu, J.; Somogyi, A.; Bailey, M.T. Social Stress Affects Colonic Inflammation, the Gut Microbiome, and Short-Chain Fatty Acid Levels and Receptors. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes-Rodrigues, R.; Henriques, A.; Pinto-Leite, R.; Faustino-Rocha, A.; Pinho-Oliveira, J.; Teixeira-Guedes, C.; Seixas, F.; Gama, A.; Colaço, B.; Colaço, A.; et al. The Effects of Repeated Oral Gavage on the Health of Male CD-1 Mice. Lab Anim. 2012, 41, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudié, F.; Auer, L.; Bernard, M.; Mariadassou, M.; Cauquil, L.; Vidal, K.; Maman, S.; Hernandez-Raquet, G.; Combes, S.; Pascal, G. FROGS: Find, Rapidly, OTUs with Galaxy Solution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouy, M.; Guindon, S.; Gascuel, O. SeaView Version 4: A Multiplatform Graphical User Interface for Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Tree Building. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guindon, S.; Dufayard, J.-F.; Lefort, V.; Anisimova, M.; Hordijk, W.; Gascuel, O. New Algorithms and Methods to Estimate Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies: Assessing the Performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010, 59, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouge, M.; Argmann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol Improves Mitochondrial Function and Protects against Metabolic Disease by Activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Yu, Z.; Chiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chai, T.; Foltz, W.; Lu, H.; Fantus, I.G.; Jin, T. Curcumin Prevents High Fat Diet Induced Insulin Resistance and Obesity via Attenuating Lipogenesis in Liver and Inflammatory Pathway in Adipocytes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e28784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A.; Štrukelj, B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Visitación, N.; Robles-Vera, I.; Toral, M.; Gómez-Guzmán, M.; Sánchez, M.; Moleón, J.; González-Correa, C.; Martín-Morales, N.; O’Valle, F.; Jiménez, R.; et al. Gut Microbiota Contributes to the Development of Hypertension in a Genetic Mouse Model of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 3708–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Vera, I.; Visitación, N.D.L.; Toral, M.; Sánchez, M.; Gómez-Guzmán, M.; O’valle, F.; Jiménez, R.; Duarte, J.; Romero, M. Toll-like Receptor 7-Driven Lupus Autoimmunity Induces Hypertension and Vascular Alterations in Mice. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 1322–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, G.; Banerjee, N.; Liang, Y.; Du, X.; Boor, P.J.; Hoffman, K.L.; Khan, M.F. Aberrant Gut Microbiome Contributes to Intestinal Oxidative Stress, Barrier Dysfunction, Inflammation and Systemic Autoimmune Responses in MRL/Lpr Mice. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 651191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Shao, T.; Li, H.; Xie, Z.; Wen, C. Alterations of the Gut Microbiome in Chinese Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Gut Pathog. 2016, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toumi, E.; Goutorbe, B.; Plauzolles, A.; Bonnet, M.; Mezouar, S.; Militello, M.; Mege, J.-L.; Chiche, L.; Halfon, P. Gut Microbiota in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients and Lupus Mouse Model: A Cross Species Comparative Analysis for Biomarker Discovery. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 943241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, M.A.; Esmaeel, N.E.; Makram, W.K.; Sharaf, D.M.; Gebriel, M.G. Altered Profile of Fecal Microbiota in Newly Diagnosed Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Egyptian Patients. Int. J. Microbiol. 2021, 2021, 9934533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widhani, A.; Djauzi, S.; Suyatna, F.D.; Dewi, B.E. Changes in Gut Microbiota and Systemic Inflammation after Synbiotic Supplementation in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Cells 2022, 11, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liao, X.; Sparks, J.B.; Luo, X.M. Dynamics of Gut Microbiota in Autoimmune Lupus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 7551–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giani, A.; Pagliari, S.; Zampolli, J.; Forcella, M.; Fusi, P.; Bruni, I.; Campone, L.; Di Gennaro, P. Characterization of the Biological Activities of a New Polyphenol-Rich Extract from Cinnamon Bark on a Probiotic Consortium and Its Action after Enzymatic and Microbial Fermentation on Colorectal Cell Lines. Foods 2022, 11, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Maldonado, A.F.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M.G. Structure-Function Relationships of the Antibacterial Activity of Phenolic Acids and Their Metabolism by Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 111, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X. Lactobacillus: Friend or Foe for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus? Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 883747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, J.Y. Cinnamon Subcritical Water Extract Attenuates Intestinal Inflammation and Enhances Intestinal Tight Junction in a Caco-2 and RAW264.7 Co-Culture Model. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4350–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.; Mao, H.; Lu, X.; Shi, T.; Wang, J. Cinnamaldehyde Promotes the Intestinal Barrier Functions and Reshapes Gut Microbiome in Early Weaned Rats. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 748503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A Taxonomic Note on the Genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 Novel Genera, Emended Description of the Genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and Union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Chen, A.; Xie, A.; Liu, X.; Jiang, S.; Yu, R. Limosilactobacillus reuteri in Immunomodulation: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Applications. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1228754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Hsu, K.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Tzang, B.-S. Lactobacillus paracasei GMNL-32, Lactobacillus reuteri GMNL-89 and L. reuteri GMNL-263 Ameliorate Hepatic Injuries in Lupus-Prone Mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manirarora, J.N.; Kosiewicz, M.M.; Alard, P. Feeding Lactobacilli Impacts Lupus Progression in (NZBxNZW) F1 Lupus-Prone Mice by Enhancing Immunoregulation. Autoimmunity 2020, 53, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarra-Ruiz, D.F.; El Beidaq, A.; Iñiguez, A.J.; Lubrano Di Ricco, M.; Manfredo Vieira, S.; Ruff, W.E.; Mubiru, D.; Fine, R.L.; Sterpka, J.; Greiling, T.M.; et al. A Diet-Sensitive Commensal Lactobacillus Strain Mediates TLR7-Dependent Systemic Autoimmunity. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, R.; Chin, S.-F.; Shaharir, S.S.; Cham, Q.S. Involvement of Gut Microbiota in SLE and Lupus Nephritis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moleón, J.; González-Correa, C.; Miñano, S.; Robles-Vera, I.; de la Visitación, N.; Barranco, A.M.; Gómez-Guzmán, M.; Sánchez, M.; Riesco, P.; Guerra-Hernández, E.; et al. Protective Effect of Microbiota-Derived Short Chain Fatty Acids on Vascular Dysfunction in Mice with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Induced by Toll like Receptor 7 Activation. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 198, 106997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Tang, B.; Wang, Y.; Shen, M.; Ping, Y.; Wang, L.; Su, J. Cinnamon Oil Solid Self-Microemulsion Mediates Chronic Mild Stress-Induced Depression in Mice by Modulating Monoamine Neurotransmitters, Corticosterone, Inflammation Cytokines, and Intestinal Flora. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xu, H.; Yang, C.; Song, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Miao, J. Cinnamaldehyde Microcapsules Enhance Bioavailability and Regulate Intestinal Flora in Mice. Food Chem. X 2022, 15, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.D.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, K.-T.; Kim, J.Y. Cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia) Water Extract Improves Diarrhea Symptoms by Changing the Gut Environment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Food. Funct. 2023, 14, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A.A.; Roberts, K.M.; Gundersen, A.; Farris, Y.; Zwickey, H.; Bradley, R.; Weir, T.L. Relationships between Habitual Polyphenol Consumption and Gut Microbiota in the INCLD Health Cohort. Nutrients 2024, 16, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.J. Glycolysis for Microbiome Generation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.-L.; Ni, W.-W.; Zhang, Q.-M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H.-Y.; Du, P.; Hou, J.-C.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Cinnamon Essential Oil on Gut Microbiota in the Mouse Model of Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 64, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredo Vieira, S.; Hiltensperger, M.; Kumar, V.; Zegarra-Ruiz, D.; Dehner, C.; Khan, N.; Costa, F.R.C.; Tiniakou, E.; Greiling, T.; Ruff, W.; et al. Translocation of a Gut Pathobiont Drives Autoimmunity in Mice and Humans. Science 2018, 359, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaks, Z.; Winans, T.; Caza, T.; Fernandez, D.; Liu, Y.; Landas, S.K.; Banki, K.; Perl, A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Liver and Antiphospholipid Antibody Production Precede Disease Onset and Respond to Rapamycin in Lupus-Prone Mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 68, 2728–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.M.; Melov, S. SOD2 in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurodegeneration. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several Lines of Antioxidant Defense against Oxidative Stress: Antioxidant Enzymes, Nanomaterials with Multiple Enzyme-Mimicking Activities, and Low-Molecular-Weight Antioxidants. Arch. Toxicol. 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-C.; Wang, S.-Y.; Li, C.-C.; Liu, C.-T. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Cinnamaldehyde and Linalool from the Leaf Essential Oil of Cinnamomum osmophloeum Kanehira in Endotoxin-Induced Mice. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sham Mice | Sham Cinnamon | Sham Lupus | Lupus Cinnamon | Cinnamon Lupus Cinnamon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other genus | 46.4 | 37.2 | 36.4 | 53.5 | 51.2 |

| Lactobacillus | 6.7 | 27.9 | 13.6 | 5.4 | 21.2 |

| Limosilactobacillus | 3.5 | 12.6 | 6.6 | 6.0 | 11.2 |

| Ligilactobacillus | 1.3 | 2.5 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 2.0 |

| Dubosiella | 4.5 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 0.1 |

| Faecalibacterium | 20.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 0.0 |

| Staphylococcus | 0.3 | 5.8 | 12.5 | 5.8 | 8.2 |

| Lachnospiraceae genus | 5.2 | 5.3 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 0.4 |

| Bacteroides | 2.4 | 1.1 | 9.1 | 3.0 | 4.7 |

| Prevotella | 4.1 | 3.2 | 5.7 | 7.1 | 0.8 |

| Bifidobacterium | 5.1 | 1.2 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Maalouly, G.; Itani, T.; Fares, N. Cinnamomum cassia Modulates Key Players of Gut–Liver Axis in Murine Lupus. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010006

Maalouly G, Itani T, Fares N. Cinnamomum cassia Modulates Key Players of Gut–Liver Axis in Murine Lupus. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaalouly, Georges, Tarek Itani, and Nassim Fares. 2026. "Cinnamomum cassia Modulates Key Players of Gut–Liver Axis in Murine Lupus" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010006

APA StyleMaalouly, G., Itani, T., & Fares, N. (2026). Cinnamomum cassia Modulates Key Players of Gut–Liver Axis in Murine Lupus. Biomedicines, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010006