Glial Activation, Neuroinflammation, and Loss of Neuroprotection in Chronic Pain: Cellular Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

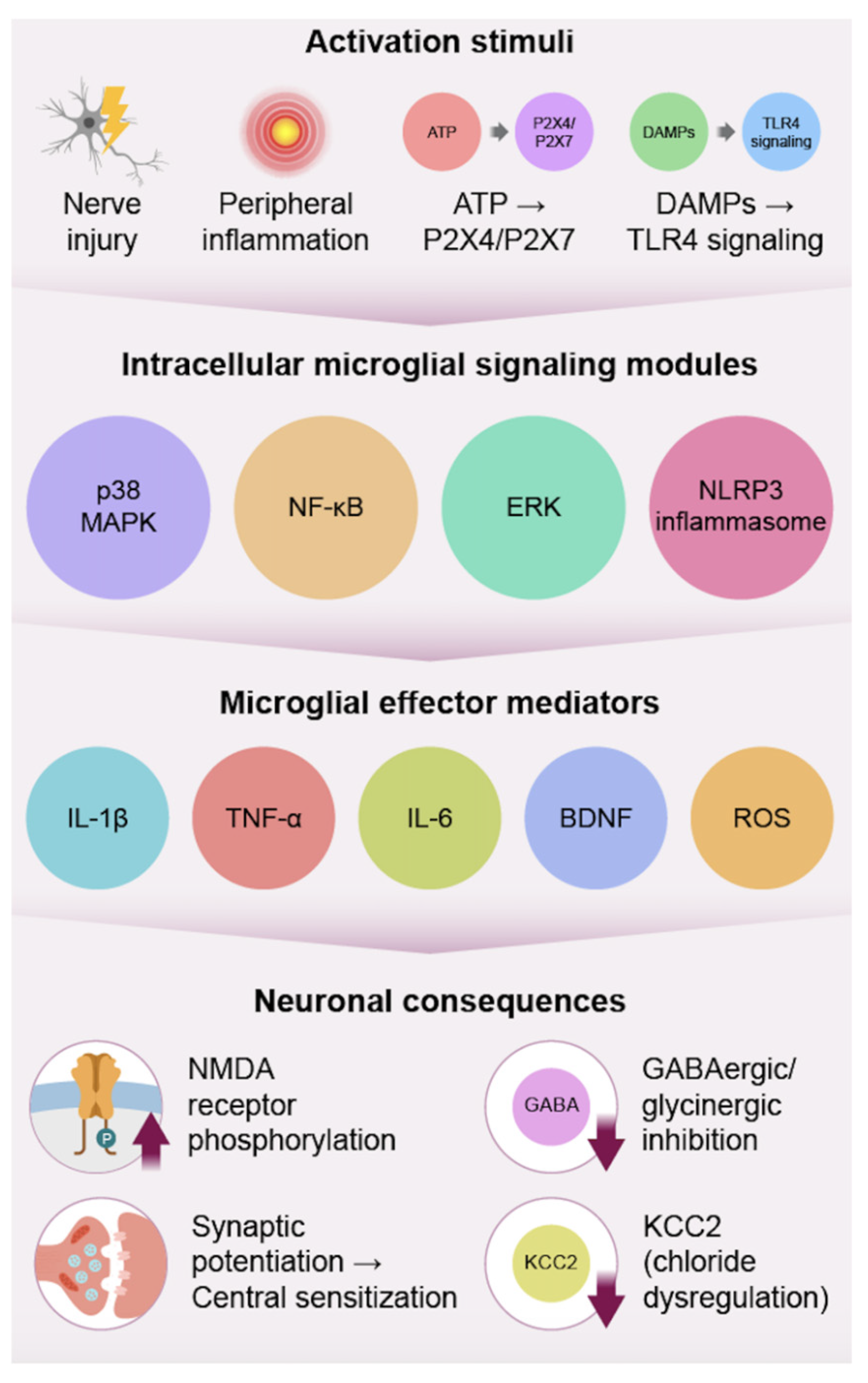

2. Microglia: Initiators of Central Sensitization

2.1. Activation Triggers

2.2. Effector Pathways

2.3. Resolution and Modulation

2.4. Oligodendrocyte Precursor Cells and Neuroinflammatory Signaling

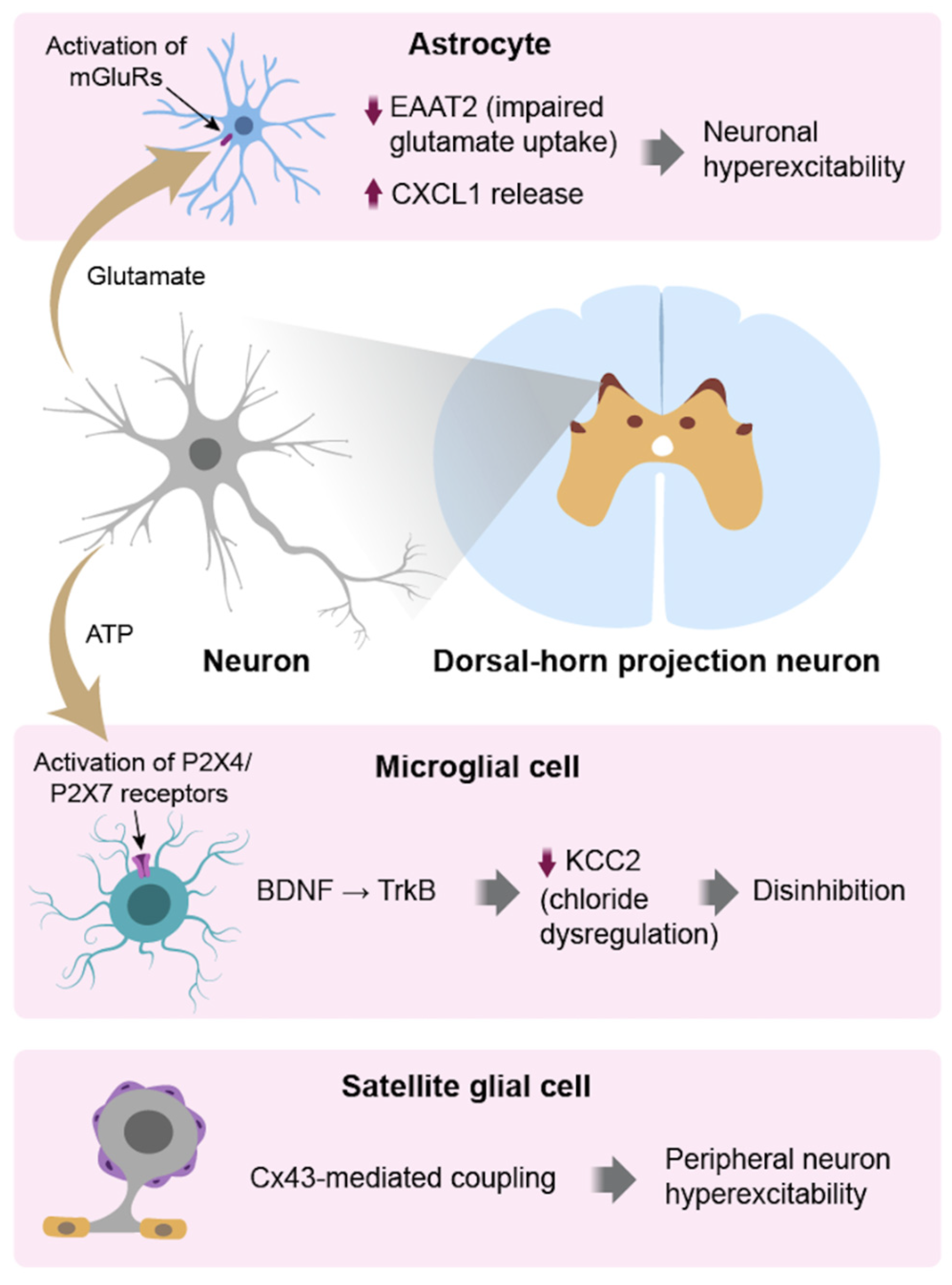

3. Astrocytes: Sustainers of Pain Chronification

3.1. Reactive Transformation

3.2. Intracellular Signaling

3.3. Cross-Talk with Microglia & Neurons

4. Satellite Glial Cells (SGCs) in the Periphery

4.1. Reactive Changes and Neuroimmune Signaling

4.2. Macrophage–SGC Cross-Talk

4.3. Functional Impact on Sensory Neurons and Pain States

5. Integrated Glial Crosstalk in Pain Circuits

6. Therapeutic Strategies

6.1. Microglial-Targeted Therapies

6.2. Glucocorticoids and Glial Modulation in Chronic Pain

6.3. Astrocytic-Targeted Therapies

6.4. Satellite Glial Cell (SGC)-Targeted Therapies

6.5. Multi-Targeted Therapies

7. Translational Gaps and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| C1q | Complement Component 1q |

| CCL2 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 |

| CX3CL1 | Fractalkine (C-X3-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1) |

| CX3CR1 | Fractalkine Receptor |

| CXCL1 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1 |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CSF1R | Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor |

| Cx43 | Connexin-43 |

| DAMPs | Danger-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| DRG | Dorsal Root Ganglion/Dorsal Root Ganglia |

| EAAT2 | Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter 2 |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GLT-1 | Glutamate Transporter 1 |

| Gq-GPCR | Gq protein-coupled receptor |

| HMGB1 | High Mobility Group Box 1 |

| IL-1α | Interleukin-1 alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| JAK | Janus Kinase |

| KCC2 | Potassium-Chloride Cotransporter 2 |

| Kir4.1 | Inward-Rectifying Potassium Channel 4.1 |

| LPA | Lysophosphatidic Acid |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| M1/M2 Phenotypes | Classically activated/alternatively activated microglia |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal Stem Cells |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 |

| NMDA receptor | N-methyl-D-aspartate Receptor |

| P2X4 | Purinergic Receptor P2X4 |

| P2X7 | Purinergic Receptor P2X7 |

| P2Y | Purinergic Receptor P2Y |

| p38 MAPK | p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| PNS | Peripheral Nervous System |

| PPAR-γ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma |

| PRRs | Pattern Recognition Receptors |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SGCs | Satellite Glial Cells |

| S100β | S100 Calcium-Binding Protein Beta |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TrkB | Tropomyosin Receptor Kinase B |

| TSPO-PET | Translocator Protein Positron Emission Tomography |

References

- Tsuda, M. Microglia-Mediated Regulation of Neuropathic Pain: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 1959–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, P.M.; Hutchinson, M.R.; Maier, S.F.; Watkins, L.R. Pathological pain and the neuroimmune interface. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, K.; Tsuda, M. Microglia in neuropathic pain: Cellular and molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grace, P.M.; Tawfik, V.L.; Svensson, C.I.; Burton, M.D.; Loggia, M.L.; Hutchinson, M.R. The Neuroimmunology of Chronic Pain: From Rodents to Humans. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.R.; Donnelly, C.R.; Nedergaard, M. Astrocytes in chronic pain and itch. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofroniew, M.V.; Vinters, H.V. Astrocytes: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanani, M.; Spray, D.C. Emerging importance of satellite glia in nervous system function and dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Butt, A.; Li, B.; Illes, P.; Zorec, R.; Semyanov, A.; Tang, Y.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocytes in human central nervous system diseases: A frontier for new therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escartin, C.; Galea, E.; Lakatos, A.; O’Callaghan, J.P.; Petzold, G.C.; Serrano-Pozo, A.; Steinhäuser, C.; Volterra, A.; Carmignoto, G.; Agarwal, A.; et al. Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D. Astrocytic and microglial cells as the modulators of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.E.E.; Nicolson, K.P.; Smith, B.H. Chronic pain: A review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e273–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelaya, C.E.; Dahlhamer, J.M.; Lucas, J.W.; Connor, E.M. Chronic Pain and High-impact Chronic Pain Among U.S. Adults, 2019. NCHS Data Brief 2020, 390, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.S.Y.; Kam, P.C. Neuroimmune mechanisms of pain: Basic science and potential therapeutic modulators. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2020, 48, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Min, Y.; Xi, D.; Wang, S.; Liu, B.; Shao, X.; Liang, Y.; He, X.; Fang, J.; Fang, J. Satellite glial cells drive the transition from acute to chronic pain in a rat model of hyperalgesic priming. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1089162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coull, J.A.M.; Beggs, S.; Boudreau, D.; Boivin, D.; Tsuda, M.; Inoue, K.; Gravel, C.; Salter, M.W.; De Koninck, Y. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature 2005, 438, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boakye, P.A.; Tang, S.J.; Smith, P.A. Mediators of Neuropathic Pain; Focus on Spinal Microglia, CSF-1, BDNF, CCL21, TNF-α, Wnt Ligands, and Interleukin 1β. Front. Pain Res. 2021, 2, 698157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Yin, C.; Fang, J.; Liu, B. The NLRP3 inflammasome: An emerging therapeutic target for chronic pain. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.-J.; Gao, Y.-J. Astrocytes in Chronic Pain: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Neurosci. Bull. 2023, 39, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orihuela, R.; McPherson, C.A.; Harry, G.J. Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Li, W.W.; Stary, C.; Clark, J.D.; Xu, S.; Xiong, X. The inflammasome as a target for pain therapy. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata-Martínez, E.; Díaz-Muñoz, M.; Vázquez-Cuevas, F.G. Glial Cells and Brain Diseases: Inflammasomes as Relevant Pathological Entities. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 929529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorge, R.E.; Mapplebeck, J.C.S.; Rosen, S.; Beggs, S.; Taves, S.; Alexander, J.K.; Martin, L.J.; Austin, J.S.; Sotocinal, S.G.; Chen, D.; et al. Different immune cells mediate mechanical pain hypersensitivity in male and female mice. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 1081–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loggia, M.L.; Chonde, D.B.; Akeju, O.; Arabasz, G.; Catana, C.; Edwards, R.R.; Hill, E.; Hsu, S.; Izquierdo-Garcia, D.; Ji, R.R.; et al. Evidence for brain glial activation in chronic pain patients. Brain 2015, 138, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, D.A.; Kim, T.U.; Chang, M.C. Minocycline for Controlling Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Narrative Review of Studies in Humans. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-S.; Tsaur, M.-L.; Chen, C.-C.; Wang, T.-Y.; Lin, C.-F.; Lai, Y.-L.; Hsu, T.-C.; Pan, Y.-Y.; Yang, C.-H.; Cheng, J.-K. Chronic intrathecal infusion of minocycline prevents the development of spinal-nerve ligation-induced pain in rats. Reg. Anesth. Pain. Med. 2007, 32, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, X.-P.; Xu, H.; Xie, C.; Ren, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, L.-X. Post-injury administration of minocycline: An effective treatment for nerve-injury induced neuropathic pain. Neurosci. Res. 2011, 70, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Shi, X.Q.; Fan, A.; West, B.; Zhang, J. Targeting macrophage and microglia activation with colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor is an effective strategy to treat injury-triggered neuropathic pain. Mol. Pain. 2018, 14, 1744806918764979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Basbaum, A.I.; Guan, Z. Contribution of colony-stimulating factor 1 to neuropathic pain. PAIN Rep. 2021, 6, e883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabeza-Fernandez, S.C.; White, J.A.; McMurran, C.E.; Gomez-Sanchez, J.A.; de la Fuente, A.G. Immune-stem cell crosstalk in the central nervous system: How oligodendrocyte progenitor cells interact with immune cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2023, 101, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, C.S.; Cui, Q.-L.; Warsi, N.M.; Durafourt, B.A.; Zorko, N.; Owen, D.R.; Antel, J.P.; Bar-Or, A. Direct and indirect effects of immune and central nervous system-resident cells on human oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghi, S.M.; Fattori, V.; Hohmann, M.S.; Verri, W.A. Contribution of Spinal Cord Oligodendrocytes to Neuroinflammatory Diseases and Pain. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 5781–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreeva, D.; Murashova, L.; Burzak, N.; Dyachuk, V. Satellite Glial Cells: Morphology, functional heterogeneity, and role in pain. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1019449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toft-Bertelsen, T.L.; Larsen, B.R.; Christensen, S.K.; Khandelia, H.; Waagepetersen, H.S.; MacAulay, N. Clearance of activity-evoked K+ transients and associated glia cell swelling occur independently of AQP4: A study with an isoform-selective AQP4 inhibitor. Glia 2020, 69, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, J.; Molina, E.; Rodriguez, A.; Woodford, S.; Nguyen, A.; Parker, G.; Lucke-Wold, B. Headache Disorders: Differentiating Primary and Secondary Etiologies. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.-S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Boyette-Davis, J.A.; Kosturakis, A.K.; Li, Y.; Yoon, S.-Y.; Walters, E.T.; Dougherty, P.M. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and its receptor CCR2 in primary sensory neurons contributes to paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. J. Pain 2013, 14, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.J.; Ji, R.-R. Chemokines, neuronal-glial interactions, and central processing of neuropathic pain. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 126, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanani, M. Satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia: From form to function. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2005, 48, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retamal, M.A.; Riquelme, M.A.; Stehberg, J.; Alcayaga, J. Connexin43 Hemichannels in Satellite Glial Cells, Can They Influence Sensory Neuron Activity? Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, R.M.; Aníbal-Silva, C.E.; Davoli-Ferreira, M.; Gomes, F.I.F.; Mendes, A.; Cavallini, M.C.M.; Fonseca, M.M.; Damasceno, S.; Andrade, L.P.; Colonna, M.; et al. Neuron-associated macrophage proliferation in the sensory ganglia is associated with peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain involving CX3CR1 signaling. eLife 2023, 12, e78515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindborg, J.A.; Niemi, J.P.; Howarth, M.A.; Liu, K.W.; Moore, C.Z.; Mahajan, D.; Zigmond, R.E. Molecular and cellular identification of the immune response in peripheral ganglia following nerve injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrini, F.; De Koninck, Y. Microglia control neuronal network excitability via BDNF signalling. Neural Plast. 2013, 2013, 429815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tse, V. Astrocytic Control of Glutamate Spillover and Extrasynaptic NMDA Receptor Activation: Implications for Neurodegenerative Disorders. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e0083242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, M.; Cui, S.; Liang, W.; Jia, Z.; Guo, F.; Ou, W.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S. The core of maintaining neuropathic pain: Crosstalk between glial cells and neurons (neural cell crosstalk at spinal cord). Brain Behav. 2023, 13, e2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, L.R.; Hutchinson, M.R.; Rice, K.C.; Maier, S.F. The “toll” of opioid-induced glial activation: Improving the clinical efficacy of opioids by targeting glia. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, L.R.; Hutchinson, M.R.; Ledeboer, A.; Wieseler-Frank, J.; Milligan, E.D.; Maier, S.F. Norman Cousins Lecture. Glia as the “bad guys”: Implications for improving clinical pain control and the clinical utility of opioids. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007, 21, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Niu, Z.; Dong, S. Spinal glia-driven neuroinflammation as a therapeutic target for neuropathic pain: Rational development of novel analgesics. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 179, 106404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledeboer, A.; Sloane, E.M.; Milligan, E.D.; Frank, M.G.; Mahony, J.H.; Maier, S.F.; Watkins, L.R. Minocycline attenuates mechanical allodynia and proinflammatory cytokine expression in rat models of pain facilitation. Pain 2005, 115, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojewska, E.; Popiolek-Barczyk, K.; Jurga, A.M.; Makuch, W.; Przewlocka, B.; Mika, J. Involvement of pro- and antinociceptive factors in minocycline analgesia in rat neuropathic pain model. J. Neuroimmunol. 2014, 277, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H.; Li, R.; Han, C.; Lu, X.; Zhang, H. Minocycline promotes posthemorrhagic neurogenesis via M2 microglia polarization via upregulation of the TrkB/BDNF pathway in rats. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 120, 1307–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.H.; Kim, H.I.; Kim, J.; Park, M.; Song, J.-H. Effects of minocycline on Na⁺ currents in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res. 2011, 1370, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.-Q.; Liu, D.-Q.; Chen, S.-P.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.-M.; Tian, Y.-K.; Wu, W.; Ye, D.-W. Minocycline as a promising therapeutic strategy for chronic pain. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Chitu, V.; Stanley, E.R.; Wszolek, Z.K.; Karrenbauer, V.D.; Harris, R.A. Inhibition of colony stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R) as a potential therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases: Opportunities and challenges. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, C.; Swartzwelter, B.; Gamboni, F.; Neff, C.P.; Richter, K.; Azam, T.; Carta, S.; Tengsdal, I.; Nemkov, T.; D’Alessandro, A.; et al. OLT1177, a β-sulfonyl nitrile compound, safe in humans, inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome and reverses the metabolic cost of inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1530–E1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, S.E.; Halai, R.; Cooper, M.A. Pharmacological inhibition of the Nod-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome with MCC950. Pharmacol. Rev. 2021, 73, 968–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, G.R.; Wenzel, T.J.; Marshall, N.; Gates, E.J.; Klegeris, A. Targeting toll-like receptor 4 to modulate neuroinflammation in central nervous system disorders. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2019, 23, 865–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwilasz, A.J.; Fulgham, S.M.G.; Duran-Malle, J.C.; Schrama, A.E.W.; Mitten, E.H.; Todd, L.S.; Patel, H.R.; Larson, T.A.; Clements, M.A.; Harris, K.M.; et al. Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 antagonism for the treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)-related pain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 93, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.B.; Ryu, J.K.; Kim, S.U.; McLarnon, J.G. Modulation of the purinergic P2X7 receptor attenuates lipopolysaccharide-mediated microglial activation and neuronal damage in inflamed brain. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 4957–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, Y.; Yamashita, T.; Sasaki, A.; Nakata, E.; Kohno, K.; Masuda, T.; Tozaki-Saitoh, H.; Imai, T.; Kuraishi, Y.; Tsuda, M.; et al. A novel P2X4 receptor–selective antagonist produces anti-allodynic effect in a mouse model of herpetic pain. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederberger, E.; Geisslinger, G. The IKK–NF-kappaB pathway: A source for novel molecular drug targets in pain therapy? FASEB J. 2008, 22, 3432–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thawkar, B.S.; Kaur, G. Inhibitors of NF-κB and P2X7/NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway in microglia: Novel therapeutic opportunities in neuroinflammation-induced early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 326, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinne, M.; Mätlik, K.; Ahonen, T.; Vedovi, F.; Zappia, G.; Moreira, V.M.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Leino, S.; Salminen, O.; Kalsó, E.; et al. Mitoxantrone, pixantrone and mitoxantrone (2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine are toll-like receptor 4 antagonists, inhibit NF-κB activation, and decrease TNF-alpha secretion in primary microglia. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 154, 105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, C.; de Bree, P.N.; Huygen, F.J.P.M.; Tiemensma, J. Glucocorticoid treatment in patients with complex regional pain syndrome: A systematic review. Eur. J. Pain 2022, 26, 2009–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, M.-Y.; Cheng, J.; Gao, N.; Li, X.-Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.-X. Dexamethasone attenuates neuropathic pain through spinal microglial expression of dynorphin A via the cAMP/PKA/p38 MAPK/CREB signaling pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 119, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babenko, V.N.; Shishkina, G.T.; Lanshakov, D.A.; Sukhareva, E.V.; Dygalo, N.N. LPS Administration Impacts Glial Immune Programs by Alternative Splicing. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, A.O.; Goursaud, S.; Desmet, N.; Hermans, E. Differential regulation of glutamate transporter subtypes by pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in cortical astrocytes from a rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, I.A.; Vissel, B. Excess cerebral TNF causing glutamate excitotoxicity rationalizes treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and neurogenic pain by anti-TNF agents. J. Neuroinflammation 2016, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gegelashvili, G.; Bjerrum, O.J. Glutamate transport system as a key constituent of glutamosome: Molecular pathology and pharmacological modulation in chronic pain. Neuropharmacology 2019, 161, 107623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, A.C.K. Current approaches to enhance glutamate transporter function and expression. J. Neurochem. 2015, 134, 982–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Park, C.-K.; Xie, R.-G.; Berta, T.; Nedergaard, M.; Ji, R.-R. Connexin-43 induces chemokine release from spinal cord astrocytes to maintain late-phase neuropathic pain in mice. Brain 2014, 137, 2193–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-M.; Wang, L.-Z.; He, B.; Xiang, Y.-K.; Fan, L.-X.; Wang, Q.; Tao, L. The gap junction inhibitor INI-0602 attenuates mechanical allodynia and depression-like behaviors induced by spared nerve injury in rats. Neuroreport 2019, 30, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, G.; Merli, D.; Verderio, C.; Abbracchio, M.P.; Ceruti, S. P2Y2 receptor antagonists as anti-allodynic agents in acute and sub-chronic trigeminal sensitization: Role of satellite glial cells. Glia 2015, 63, 1256–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemes, J.B.P.; Campos Lima, T.; Santos, D.O.; Neves, A.F.; Oliveira, F.S.; Parada, C.A.; Lotufo, C.M.C. Participation of satellite glial cells of the dorsal root ganglia in acute nociception. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 676, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshino, Y.; Okuno, T.; Saigusa, D.; Kano, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Shindou, H.; Aoki, J.; Uchida, K.; Yokomizo, T.; Ito, N. Lysophosphatidic acid receptor1/3 antagonist inhibits the activation of satellite glial cells and reduces acute nociceptive responses. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, A.X.; Madayag, A.R.; Minton, S.K.; McCarthy, K.D.; Malykhina, A.P. Sensory satellite glial Gq-GPCR activation alleviates inflammatory pain via peripheral adenosine 1 receptor activation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonello, R.; Prudente, A.S.; Lee, S.H.; Cohen, C.F.; Xie, W.; Paranjpe, A.; Roh, J.; Park, C.K.; Chung, G.; Strong, J.A.; et al. Single-cell analysis of dorsal root ganglia reveals metalloproteinase signaling in satellite glial cells and pain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 113, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderwall, A.G.; Milligan, E.D. Cytokines in Pain: Harnessing Endogenous Anti-Inflammatory Signaling for Improved Pain Management. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanao-Kanda, M.; Kanda, H.; Liu, S.; Kawamata, T.; Candiotti, K.; Hao, S. EXPRESS: Viral Vector–mediated Interleukin 10 for Gene Therapy on Chronic Pain. Mol. Pain 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovsepian, S.V.; Waxman, S.G. Gene therapy for chronic pain: Emerging opportunities in target-rich peripheral nociceptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 24, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey, S.; Aghaeepour, N.; Gaudilliere, B.; Kao, M.-C.; Kaptan, M.; Lannon, E.; Pfyffer, D.; Weber, K. Innovations in acute and chronic pain biomarkers: Enhancing diagnosis and personalized therapy. Reg. Anesth. Pain. Med. 2025, 50, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluka, K.A.; Wager, T.D.; Sutherland, S.P.; Labosky, P.A.; Balach, T.; Bayman, O.E.; Berardi, G.; Brummett, C.M.; Burns, J.; Buvanendran, A.; et al. Predicting chronic postsurgical pain: Current evidence and a novel program to develop predictive biomarker signatures. Pain 2023, 164, 1912–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucke-Wold, B.; Karamian, A. Effect of esketamine on reducing postpartum pain and depression. World J. Clin. Cases 2025, 13, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryk, M.; Karnas, E.; Mlost, J.; Zuba-Surma, E.; Starowicz, K. Mesenchymal stem cells and extracellular vesicles for the treatment of pain: Current status and perspectives. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 4281–4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Xiu, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, T.; Wang, P.; Men, L.; Qiu, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhao, J. Exosomal GDNF from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells moderates neuropathic pain in a rat model of chronic constriction injury. Neuromolecular Med. 2024, 26, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.-J.; Pi, X.-W.; Hu, D.-X.; Liu, X.-P.; Wu, M.-M. Advances and challenges in cell therapy for neuropathic pain based on mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1536566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Glial Cell Type | Major Mediators | Mechanistic Effect | Neuroprotection Function Lost | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microglia | IL-1β, TNF-α, BDNF | Central sensitization | Impaired debris clearance; loss of anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype; oxidative stress | Neuropathic pain |

| Astrocytes | CXCL1, CCL2 (MCP-1), IL-6, EAAT2 ↓, ATP | Persistent excitability | Loss of metabolic support; impaired glutamate uptake; impaired potassium buffering | Chronic back pain |

| Satellite Glial cells | IL-6, Cx43 | DRG cross-excitation | Loss of ion buffering; reduced ganglionic insulation; impaired inflammatory control | Orofacial pain |

| Target | Mechanism | Glial Cell Type | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4 | DAMP-driven | Microglia | TLR-4 inhibitors |

| P2X4/P2X7 | ATP-dependent purinergic activation | Microglia | Antagonists |

| NF-κB | Pro-inflammatory transcription | Microglia/astrocytes | NF-κB inhibitors |

| CSF1R | Proliferation and activation | Microglia | CSF1R inhibitors |

| Minocycline | Broad glial suppression | Microglia | Repurposed drug |

| NLRP3 | IL-1β maturation | Microglia/astrocytes | Inflammasome inhibitors |

| CXCL1/CXCR2 | Chemokine-driven excitability | Astrocytes | CXCL1/CXCR2 inhibitors |

| EAAT2 | Impaired glutamate uptake | Astrocytes | EAAT2 upregulators |

| Microglial and astrocytic inflammatory signaling pathways | Modulates glial inflammatory signaling | Microglia/astrocytes | MSC-derived exosomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

McKenzie, A.; Dombrower, R.; Theeraphapphong, N.; McKenzie, S.; Hijazin, M.A. Glial Activation, Neuroinflammation, and Loss of Neuroprotection in Chronic Pain: Cellular Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010058

McKenzie A, Dombrower R, Theeraphapphong N, McKenzie S, Hijazin MA. Glial Activation, Neuroinflammation, and Loss of Neuroprotection in Chronic Pain: Cellular Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcKenzie, Alyssa, Rachel Dombrower, Nitchanan Theeraphapphong, Sophia McKenzie, and Munther A. Hijazin. 2026. "Glial Activation, Neuroinflammation, and Loss of Neuroprotection in Chronic Pain: Cellular Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010058

APA StyleMcKenzie, A., Dombrower, R., Theeraphapphong, N., McKenzie, S., & Hijazin, M. A. (2026). Glial Activation, Neuroinflammation, and Loss of Neuroprotection in Chronic Pain: Cellular Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines, 14(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010058