Adipose Tissue and Central Nervous System Crosstalk: Roles in Pain and Cognitive Dysfunction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Anatomical and Neural Foundations of Adipose–CNS Communication

2.1. Sympathetic Nervous Regulation of Adipose Tissue

2.2. Sympathetic-Derived Signaling Factors in Adipose Tissue

2.3. Sensory Innervation in Adipose Tissue Function

2.4. Sensory-Derived Signaling Factors in Adipose Regulation

2.5. Adipokines-Derived Signaling in Central Neural Regulation

3. Advances in Adipose Tissue-Pain Crosstalk

3.1. Adipose Tissue Modulation of Pain

3.2. Immune and Lipid Mediators in Adipose-Pain Crosstalk

3.3. Impact of Pain on Adipose Tissue

3.4. Neural Circuits and Sex-Specific Adipokine Dynamics in Pain-Adipose Crosstalk

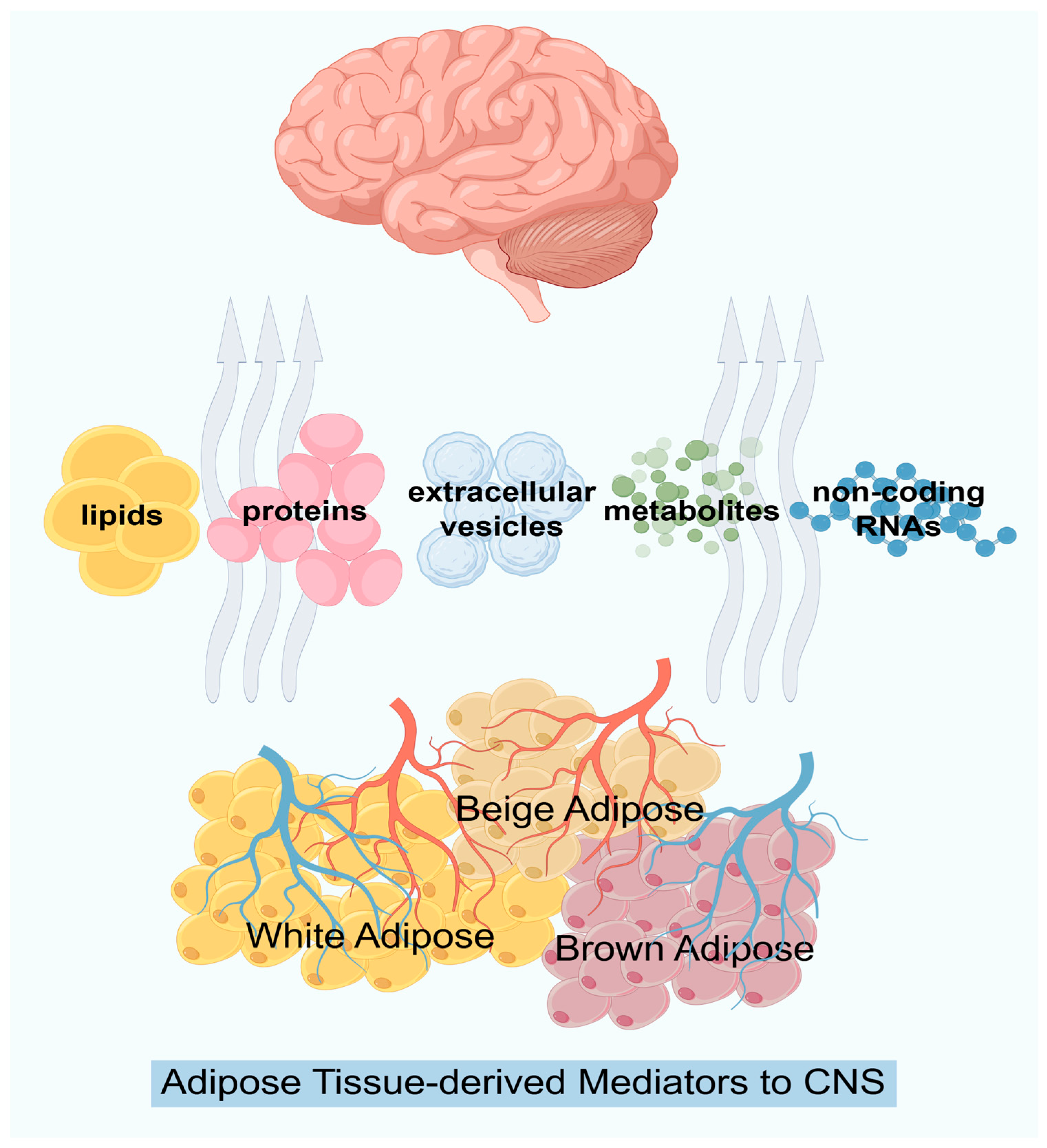

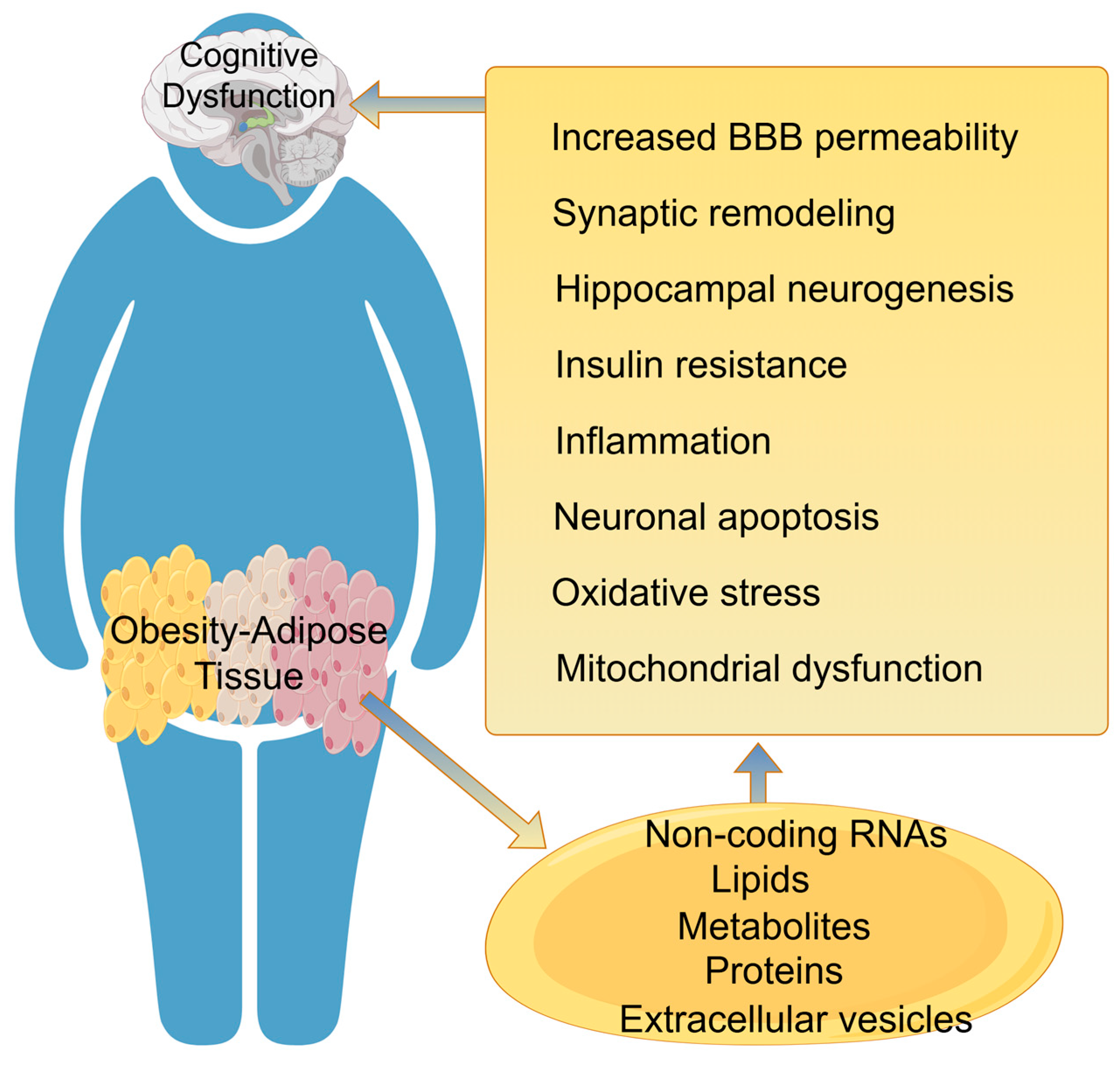

4. Adipose Tissue Regulates Cognitive Dysfunction

4.1. Changes in the Structure and Function of the Blood–Brain Barrier

4.2. Hippocampal Neurogenesis

4.3. Synaptic Plasticity

4.4. Neuroinflammation

4.5. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

5. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

- (1)

- Source Control: Reducing adipose inflammation through weight loss (lifestyle, pharmacotherapy, or bariatric surgery) remains foundational. Bariatric surgery, for instance, reverses neurogenic obesity patterns after spinal cord injury.

- (2)

- Signal Modulation: Neutralizing specific deleterious mediators (e.g., anti-IL-1β therapies) or boosting protective ones (e.g., adiponectin sensitizers) are active areas of research. Nutritional interventions, such as omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation, show promise in modulating pain pathways, although high ω-6 intake may exacerbate pain.

- (3)

- Neural Circuit Intervention: Modulating the sympathetic or sensory innervation of fat pharmacologically or via bioelectronic medicine could normalize adipose function.

- (4)

- CNS Protection: Compounds that mitigate neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, or mitochondrial dysfunction, such as GlyNAC supplementation, which improves glutathione deficiency and cognition, may be beneficial.

- (5)

- Regenerative Approaches: Interestingly, autologous fat grafting has shown correlation with improvement in localized pain syndromes, potentially via adipose-derived stem cells, highlighting a paradoxical therapeutic use of adipose tissue itself.

- (1)

- Temporal Dynamics: Delineate the sequence of events from early adipose expansion to the establishment of chronic pain and cognitive decline.

- (2)

- Spatial Specificity: Determine if different adipose depots (visceral vs. subcutaneous) release distinct EV cargos or signals with selective effects on specific brain regions.

- (3)

- Mechanistic Resolution: Employ single-cell and spatial transcriptomics in both adipose and CNS tissues to map precise cellular dialogues.

- (4)

- Sex-Specific Therapeutics: Develop and test interventions that account for the sexually dimorphic nature of adipose signaling.

- (5)

- Causal Validation in Humans: Translate mechanistic insights from animal models using human biomarkers, neuroimaging, and targeted clinical trials.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouchi, N.; Parker, J.L.; Lugus, J.J.; Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, R.; Ganbold, K.; Sparman, N.Z.R.; Rajbhandari, P. Immune regulatory crosstalk in adipose tissue thermogenesis. Compr. Physiol. 2025, 15, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Song, C.K.; Giordano, A.; Cinti, S.; Bartness, T.J. Sensory or sympathetic white adipose tissue denervation differentially affects depot growth and cellularity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 288, R1028–R1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diculescu, I.; Stoica, M. Fluorescence histochemical investigation on the adrenergic innervation of the white adipose tissue in the rat. J. Neuro-Viscer. Relat. 1970, 32, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, K.; Luo, P.; Li, Z.; Xiao, F.; Jiang, H.; Wu, S.; Tang, M.; Yuan, F.; Li, X.; et al. Hypothalamic slc7a14 accounts for aging-reduced lipolysis in white adipose tissue of male mice. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretson, J.T.; Szymanski, L.A.; Schwartz, G.J.; Xue, B.; Ryu, V.; Bartness, T.J. Lipolysis sensation by white fat afferent nerves triggers brown fat thermogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, F.; Klein Wolterink, R.G.J.; Godinho-Silva, C.; Domingues, R.G.; Ribeiro, H.; da Silva, J.A.; Mahú, I.; Domingos, A.I.; Veiga-Fernandes, H. Neuro-mesenchymal units control ilc2 and obesity via a brain-adipose circuit. Nature 2021, 597, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellen, K.E.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Obesity-induced inflammatory changes in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1785–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Ji, X.; An, Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, G.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xia, Y. The associations of general, central, visceral obesity, and body fat percentage with cognitive impairment in the elderly: Meta-analysis and mendelian randomization study. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wewege, M.A.; Desai, I.; Honey, C.; Coorie, B.; Jones, M.D.; Clifford, B.K.; Leake, H.B.; Hagstrom, A.D. The effect of resistance training in healthy adults on body fat percentage, fat mass and visceral fat: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J.; Lundberg, J.M.; Hökfelt, T.; Terenius, L.; Goldstein, M. ‘Neuropeptide tyrosine’ (npy) is co-stored with noradrenaline in vascular but not in parenchymal sympathetic nerves of brown adipose tissue. Exp. Cell Res. 1986, 164, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, A.; Song, C.K.; Bowers, R.R.; Ehlen, J.C.; Frontini, A.; Cinti, S.; Bartness, T.J. White adipose tissue lacks significant vagal innervation and immunohistochemical evidence of parasympathetic innervation. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006, 291, R1243–R1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartness, T.J.; Liu, Y.; Shrestha, Y.B.; Ryu, V. Neural innervation of white adipose tissue and the control of lipolysis. Front. Neuroendocr. 2014, 35, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, T.; O’Hare, J.; Diggs-Andrews, K.; Schweiger, M.; Cheng, B.; Lindtner, C.; Zielinski, E.; Vempati, P.; Su, K.; Dighe, S.; et al. Brain insulin controls adipose tissue lipolysis and lipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himms-Hagen, J.; Cui, J.; Lynn Sigurdson, S. Sympathetic and sensory nerves in control of growth of brown adipose tissue: Effects of denervation and of capsaicin. Neurochem. Int. 1990, 17, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, P.L.; Rothwell, N.J.; Stock, M.J. Influence of subdiaphragmatic vagotomy and brown fat sympathectomy on thermogenesis in rats. Am. J. Physiol. 1985, 249, E239–E243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwami, M.; Alkayed, F.; Shiina, T.; Taira, K.; Shimizu, Y. Activation of brown adipose tissue thermogenesis by electrical stimulation to the dorsal surface of the tissue in rats. Biomed. Res. 2013, 34, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Sanchez, N.; Sweeney, O.; Sidarta-Oliveira, D.; Caron, A.; Stanley, S.A.; Domingos, A.I. The sympathetic nervous system in the 21st century: Neuroimmune interactions in metabolic homeostasis and obesity. Neuron 2022, 110, 3597–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ding, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zeng, W. Dense intra-adipose sympathetic arborizations are essential for cold-induced beiging of mouse white adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 686–692.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tao, C.; Shao, M.; Zhao, S.; Huang, W.; Yao, T.; Johnson, J.A.; Liu, T.; Cypess, A.M.; et al. Connexin 43 mediates white adipose tissue beiging by facilitating the propagation of sympathetic neuronal signals. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, T.J.; Huang, P.; Huang, T.L.; Xue, R.; McDougall, L.E.; Townsend, K.L.; Cypess, A.M.; Mishina, Y.; Gussoni, E.; Tseng, Y.H. Brown-fat paucity due to impaired bmp signalling induces compensatory browning of white fat. Nature 2013, 495, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willows, J.W.; Blaszkiewicz, M.; Townsend, K.L. The sympathetic innervation of adipose tissues: Regulation, functions, and plasticity. Compr. Physiol. 2023, 13, 4985–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniyadath, B.; Zhang, Q.; Gupta, R.K.; Mandrup, S. Adipose tissue at single-cell resolution. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 386–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngstrom, T.G.; Bartness, T.J. Catecholaminergic innervation of white adipose tissue in siberian hamsters. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1995, 268, R744–R751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamshad, M.; Aoki, V.T.; Adkison, M.G.; Warren, W.S.; Bartness, T.J. Central nervous system origins of the sympathetic nervous system outflow to white adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 1998, 275, R291–R299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.K.; Bartness, T.J. Cns sympathetic outflow neurons to white fat that express mel receptors may mediate seasonal adiposity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2001, 281, R666–R672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, R.R.; Festuccia, W.T.; Song, C.K.; Shi, H.; Migliorini, R.H.; Bartness, T.J. Sympathetic innervation of white adipose tissue and its regulation of fat cell number. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004, 286, R1167–R1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdikari, A.; Cacciottolo, T.; Henning, E.; Mendes de Oliveira, E.; Keogh, J.M.; Farooqi, I.S. Visualization of sympathetic neural innervation in human white adipose tissue. Open Biol. 2022, 12, 210345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueiras, R.; Wiedmer, P.; Perez-Tilve, D.; Veyrat-Durebex, C.; Keogh, J.M.; Sutton, G.M.; Pfluger, P.T.; Castaneda, T.R.; Neschen, S.; Hofmann, S.M.; et al. The central melanocortin system directly controls peripheral lipid metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3475–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.Z.; Xie, H.; Du, X.; Zhou, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, W.; Cai, S.; et al. A parabrachial-hypothalamic parallel circuit governs cold defense in mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnstock, G.; Sneddon, P. Evidence for atp and noradrenaline as cotransmitters in sympathetic nerves. Clin. Sci. 1985, 68, 89s–92s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S. Β-adrenoceptor signaling networks in adipocytes for recruiting stored fat and energy expenditure. Front. Endocrinol. 2011, 2, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granneman, J.G.; Li, P.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, Y. Metabolic and cellular plasticity in white adipose tissue i: Effects of beta3-adrenergic receptor activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 289, E608–E616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseyer, V.D.; Granneman, J.G. Adrenergic regulation of cellular plasticity in brown, beige/brite and white adipose tissues. Adipocyte 2016, 5, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachman, E.S.; Dhillon, H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Cinti, S.; Bianco, A.C.; Kobilka, B.K.; Lowell, B.B. Betaar signaling required for diet-induced thermogenesis and obesity resistance. Science 2002, 297, 843–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douris, N.; Desai, B.N.; Fisher, F.M.; Cisu, T.; Fowler, A.J.; Zarebidaki, E.; Nguyen, N.L.T.; Morgan, D.A.; Bartness, T.J.; Rahmouni, K.; et al. Beta-adrenergic receptors are critical for weight loss but not for other metabolic adaptations to the consumption of a ketogenic diet in male mice. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrović, V.; Buzadzić, B.; Korać, A.; Vasilijević, A.; Janković, A.; Korać, B. No modulates the molecular basis of rat interscapular brown adipose tissue thermogenesis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 152, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Yoshida, T.; Nishimura, M.; Nakanishi, T.; Kondo, M.; Yoshimura, M. Beta-3 adrenergic agonist, brl-26830a, and alpha/beta blocker, arotinolol, markedly increase regional blood flow in the brown adipose tissue in anesthetized rats. Jpn. Circ. J. 1992, 56, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.; Tonello, C.; Bulbarelli, A.; Cozzi, V.; Cinti, S.; Carruba, M.O.; Nisoli, E. Evidence for a functional nitric oxide synthase system in brown adipocyte nucleus. FEBS Lett. 2002, 514, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L. Small molecules for fat combustion: Targeting obesity. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2019, 9, 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yao, L.; Gallo-Ferraz, A.L.; Bombassaro, B.; Simões, M.R.; Abe, I.; Chen, J.; Sarker, G.; Ciccarelli, A.; Zhou, L.; et al. Sympathetic neuropeptide y protects from obesity by sustaining thermogenic fat. Nature 2024, 634, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Cline, M.A.; Gilbert, E.R. Hypothalamus-adipose tissue crosstalk: Neuropeptide y and the regulation of energy metabolism. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire-Agulleiro, Ó.; López, M. Sympathetic npy ignites adipose tissue. Neuron 2024, 112, 3816–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turtzo, L.C.; Marx, R.; Lane, M.D. Cross-talk between sympathetic neurons and adipocytes in coculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 12385–12390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Guan, H.; Arany, E.; Hill, D.J.; Cao, X. Neuropeptide y is produced in visceral adipose tissue and promotes proliferation of adipocyte precursor cells via the y1 receptor. Faseb J. 2008, 22, 2452–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.E.; Kitlinska, J.B.; Tilan, J.U.; Li, L.; Baker, S.B.; Johnson, M.D.; Lee, E.W.; Burnett, M.S.; Fricke, S.T.; Kvetnansky, R.; et al. Neuropeptide y acts directly in the periphery on fat tissue and mediates stress-induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnstock, G. Purinergic cotransmission. F1000 Biol. Rep. 2009, 1, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnstock, G.; Gentile, D. The involvement of purinergic signalling in obesity. Purinergic Signal. 2018, 14, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, R.; Ricquier, D.; Cinti, S. Th-, npy-, sp-, and cgrp-immunoreactive nerves in interscapular brown adipose tissue of adult rats acclimated at different temperatures: An immunohistochemical study. J. Neurocytol. 1998, 27, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.K.; Schwartz, G.J.; Bartness, T.J. Anterograde transneuronal viral tract tracing reveals central sensory circuits from white adipose tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 296, R501–R511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, C.H.; Bartness, T.J. Anterograde transneuronal viral tract tracing reveals central sensory circuits from brown fat and sensory denervation alters its thermogenic responses. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2012, 302, R1049–R1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.L.T.; Xue, B.; Bartness, T.J. Sensory denervation of inguinal white fat modifies sympathetic outflow to white and brown fat in siberian hamsters. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 190, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, M.K.; Holzer, P. Neurogenic inflammation. I. Basic mechanisms, physiology and pharmacology. Anasthesiol. Intensiv. Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2002, 37, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, F.A.; King, R.; Smillie, S.J.; Kodji, X.; Brain, S.D. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: Physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 1099–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, M.; Shimouchi, A.; Ikeda, S.; Ninomiya, I.; Sunagawa, K.; Kangawa, K.; Matsuo, H. Vasodilator effects of adrenomedullin on small pulmonary arteries and veins in anaesthetized cats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 121, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, C.P.; Arleth, A.J.; Aiyar, N.; Bhatnagar, P.K.; Lysko, P.G.; Feuerstein, G. Cgrp stimulates the adhesion of leukocytes to vascular endothelial cells. Peptides 1992, 13, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Kamiyoshi, A.; Sakurai, T.; Ichikawa-Shindo, Y.; Kawate, H.; Yang, L.; Tanaka, M.; Xian, X.; Imai, A.; Zhai, L.; et al. Endogenous calcitonin gene-related peptide regulates lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis in male mice. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 1194–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.B.; Young, A.D.; Marriott, I. The therapeutic potential of targeting substance p/nk-1r interactions in inflammatory cns disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.M.; O’Connell, J.; O’Brien, D.I.; Goode, T.; Bredin, C.P.; Shanahan, F. The role of substance p in inflammatory disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2004, 201, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideri, A.; Bakirtzi, K.; Shih, D.Q.; Koon, H.W.; Fleshner, P.; Arsenescu, R.; Arsenescu, V.; Turner, J.R.; Karagiannides, I.; Pothoulakis, C. Substance p mediates pro-inflammatory cytokine release from mesenteric adipocytes in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 1, 420–432. [Google Scholar]

- Miegueu, P.; St-Pierre, D.H.; Lapointe, M.; Poursharifi, P.; Lu, H.; Gupta, A.; Cianflone, K. Substance p decreases fat storage and increases adipocytokine production in 3t3-l1 adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2013, 304, G420–G427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Jing, J.; Wu, R.; Cao, Q.; Li, F.; Li, K.; Wang, S.; Yu, L.; Schwartz, G.; Shi, H.; et al. Adipose tissue-derived neurotrophic factor 3 regulates sympathetic innervation and thermogenesis in adipose tissue. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, M. Transcriptional fingerprinting of “browning” white fat identifies nrg4 as a novel adipokine. Adipocyte 2015, 4, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, G.; Straub, R.H. The sympathetic nervous response in inflammation. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2014, 16, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, I.; Gonthier, M.P.; Orlando, P.; Martiadis, V.; De Petrocellis, L.; Cervino, C.; Petrosino, S.; Hoareau, L.; Festy, F.; Pasquali, R.; et al. Regulation, function, and dysregulation of endocannabinoids in models of adipose and beta-pancreatic cells and in obesity and hyperglycemia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 3171–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, I.; Gonthier, M.P.; Petrosino, S.; Docimo, L.; Capasso, R.; Hoareau, L.; Monteleone, P.; Roche, R.; Izzo, A.A.; Di Marzo, V. Role and regulation of acylethanolamides in energy balance: Focus on adipocytes and beta-cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 676–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, A.; Henriques, F.; Bedard, A.H.; Czech, M.P. Molecular pathways linking adipose innervation to insulin action in obesity and diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niijima, A. Afferent signals from leptin sensors in the white adipose tissue of the epididymis, and their reflex effect in the rat. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1998, 73, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvartsman, D.; Storrie-White, H.; Lee, K.; Kearney, C.; Brudno, Y.; Ho, N.; Cezar, C.; McCann, C.; Anderson, E.; Koullias, J.; et al. Sustained delivery of vegf maintains innervation and promotes reperfusion in ischemic skeletal muscles via ngf/gdnf signaling. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Sun, K.; An, Y.A.; Gu, X.; Scherer, P.E. Vegf-a-expressing adipose tissue shows rapid beiging and enhanced survival after transplantation and confers il-4-independent metabolic improvements. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmreich, D.L.; Parfitt, D.B.; Lu, X.Y.; Akil, H.; Watson, S.J. Relation between the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (hpt) axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (hpa) axis during repeated stress. Neuroendocrinology 2005, 81, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, D.; Brooks, V.L. Leptin increases: Physiological roles in the control of sympathetic nerve activity, energy balance, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, S.; Canpolat, S.; Sandal, S.; Ozcan, M.; Sarsilmaz, M.; Kelestimur, H. Effects of central and peripheral administration of leptin on pain threshold in rats and mice. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2003, 24, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.J.; Han, W.; Cao, C.Q.; Mao-Ying, Q.L.; Mi, W.L.; Wang, Y.Q. Peripheral leptin signaling mediates formalin-induced nociception. Neurosci. Bull. 2018, 34, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Mao, J. Spinal leptin contributes to the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in rodents. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Kiguchi, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ikuta, T.; Ozaki, M.; Kishioka, S. Leptin derived from adipocytes in injured peripheral nerves facilitates development of neuropathic pain via macrophage stimulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13076–13081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perruccio, A.V.; Mahomed, N.N.; Chandran, V.; Gandhi, R. Plasma adipokine levels and their association with overall burden of painful joints among individuals with hip and knee osteoarthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 41, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietta, P.; Fietta, P. Counterbalance between leptin and cortisol may be associated with fibromyalgia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 60, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, G.; Dagostino, C.; Buonocore, R.; Aloe, R.; Bonaguri, C.; Fanelli, G.; Allegri, M. The serum concentrations of leptin and mcp-1 independently predict low back pain duration. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2017, 55, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seringec Akkececi, N.; Oksuz, G.; Urfalioğlu, A.; Gunesacar, R.; Bakacak, M.; Arslan, M.; Kelleci, B.M. Preoperative serum leptin level is associated with preoperative pain threshold and postoperative analgesic consumption in patients undergoing cesarean section. Med. Princ. Pract. 2019, 28, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannitti, T.; Graham, A.; Dolan, S. Adiponectin-mediated analgesia and anti-inflammatory effects in rat. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannitti, T.; Graham, A.; Dolan, S. Increased central and peripheral inflammation and inflammatory hyperalgesia in zucker rat model of leptin receptor deficiency and genetic obesity. Exp. Physiol. 2012, 97, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, H.; Tai, L.W.; Gu, P.; Cheung, C.W. Adiponectin regulates thermal nociception in a mouse model of neuropathic pain. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 1356–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlin, B.L.; Alexander, G.; Tabby, D.; Reichenberger, E. Oligomerization state-dependent elevations of adiponectin in chronic daily headache. Neurology 2008, 70, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taouis, M.; Benomar, Y. Is resistin the master link between inflammation and inflammation-related chronic diseases? Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2021, 533, 111341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yin, C.; Lan, X.; Wu, L.; Du, X.; Griffiths, H.R.; Gao, D. Adipokines, hepatokines and myokines: Focus on their role and molecular mechanisms in adipose tissue inflammation. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 873699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Lu, Y.C.; Kuo, S.J.; Lin, C.Y.; Tsai, C.H.; Liu, S.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Wang, S.W.; Tang, C.H. Resistin enhances il-1β and tnf-α expression in human osteoarthritis synovial fibroblasts by inhibiting mir-149 expression via the mek and erk pathways. Faseb J. 2020, 34, 13671–13684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Kuo, S.J.; Liu, S.C.; Lu, Y.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Wang, S.W.; Tang, C.H. Resistin enhances vcam-1 expression and monocyte adhesion in human osteoarthritis synovial fibroblasts by inhibiting mir-381 expression through the pkc, p38, and jnk signaling pathways. Cells 2020, 9, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozumi, J.; Sumitani, M.; Nishizawa, D.; Nagashima, M.; Ikeda, K.; Abe, H.; Kato, R.; Kusakabe, Y.; Yamada, Y. Resistin is a novel marker for postoperative pain intensity. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 128, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, G.R.; Rueff, A.; Mendell, L.M. Peripheral and central mechanisms of ngf-induced hyperalgesia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994, 6, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, M.A.; Ruparel, S.; Green, D.P.; Chen, P.B.; Por, E.D.; Jeske, N.A.; Gao, X.; Flores, E.R.; Hargreaves, K.M. Persistent nociception triggered by nerve growth factor (ngf) is mediated by trpv1 and oxidative mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 8593–8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Trayhurn, P. Acute and prolonged effects of tnf-alpha on the expression and secretion of inflammation-related adipokines by human adipocytes differentiated in culture. Pflug. Arch. 2006, 452, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Shi, R.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, W. Association of visceral adiposity index and chronic pain in us adults: A cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kifle, Z.D.; Tian, J.; Aitken, D.; Melton, P.E.; Cicuttini, F.; Jones, G.; Pan, F. MRI-derived abdominal adipose tissue is associated with multisite and widespread chronic pain. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.T.; Pan, F.; Gao, W.; Hu, S.S.; Wang, D. Involvement of macrophages and spinal microglia in osteoarthritis pain. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2021, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manferdini, C.; Paolella, F.; Gabusi, E.; Gambari, L.; Piacentini, A.; Filardo, G.; Fleury-Cappellesso, S.; Barbero, A.; Murphy, M.; Lisignoli, G. Adipose stromal cells mediated switching of the pro-inflammatory profile of m1-like macrophages is facilitated by pge2, In vitro evaluation. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2017, 25, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domoto, R.; Sekiguchi, F.; Tsubota, M.; Kawabata, A. Macrophage as a peripheral pain regulator. Cells 2021, 10, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzonico Jost, T.; Lozito, A.; Mangani, D.; Raimondi, A.; Klinger, F.; Morone, D.; Klinger, M.; Grassi, F.; Vinci, V. Cd304+ adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell abundance in autologous fat grafts highly correlates with improvement of localized pain syndromes. Pain 2024, 165, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, R.; Zhang, W.; Li, C.; Tian, C.; Han, C.; et al. Mir-125b-5p delivered by adipose-derived stem cell exosomes alleviates hypertrophic scarring by suppressing smad2. Burn. Trauma 2024, 12, tkad064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.; Crowley, C.; Lim, S.K.; Khan, W.S. Autologous adipose tissue grafting for the management of the painful scar. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prego-Dominguez, J.; Hadrya, F.; Takkouche, B. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. Physician 2016, 19, 521–535. [Google Scholar]

- Durán, A.M.; Beeson, W.L.; Firek, A.; Cordero-MacIntyre, Z.; De León, M. Dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty-acid supplementation upregulates protective cellular pathways in patients with type 2 diabetes exhibiting improvement in painful diabetic neuropathy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J.T.; LoCoco, P.M.; Furr, A.R.; Bendele, M.R.; Tram, M.; Li, Q.; Chang, F.M.; Colley, M.E.; Samenuk, G.M.; Arris, D.A.; et al. Elevated dietary ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids induce reversible peripheral nerve dysfunction that exacerbates comorbid pain conditions. Nat. Metab. 2021, 3, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, D.W.; Bigford, G.E.; Farkas, G.J. The physiology of neurogenic obesity: Lessons from spinal cord injury research. Obes. Facts 2023, 16, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, V.; Rossi, C.; Pieroni, L.; De Angelis, F.; Giacovazzo, G.; Cicalini, I.; Ciavardelli, D.; Pavone, F.; Coccurello, R.; Marinelli, S. Sex-specific adipose tissue’s dynamic role in metabolic and inflammatory response following peripheral nerve injury. iScience 2023, 26, 107914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.J.; Du, W.J.; Liu, R.; Zan, G.Y.; Ye, B.L.; Li, Q.; Sheng, Z.H.; Yuan, Y.W.; Song, Y.J.; Liu, J.G.; et al. Paraventricular nucleus-central amygdala oxytocinergic projection modulates pain-related anxiety-like behaviors in mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 3493–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Bair-Marshall, C.; Xu, H.; Jee, H.J.; Zhu, E.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Q.; Lefevre, A.; Chen, Z.S.; et al. Oxytocin promotes prefrontal population activity via the pvn-pfc pathway to regulate pain. Neuron 2023, 111, 1795–1811.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, J.D.; Veinante, P.; Uhl-Bronner, S.; Vergnano, A.M.; Freund-Mercier, M.J.; Schlichter, R.; Poisbeau, P. Oxytocin-induced antinociception in the spinal cord is mediated by a subpopulation of glutamatergic neurons in lamina i-ii which amplify gabaergic inhibition. Mol. Pain 2008, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, T.; Kawasaki, M.; Hashimoto, H.; Ishikura, T.; Yoshimura, M.; Ohkubo, J.I.; Maruyama, T.; Motojima, Y.; Sabanai, K.; Mori, T.; et al. Fluorescent visualisation of oxytocin in the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial/-spinal pathways after chronic inflammation in oxytocin-monomeric red fluorescent protein 1 transgenic rats. J. Neuroendocr. 2015, 27, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yan, B.; Yang, D.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Shi, X.; Tian, G.; Liang, X. Serum adiponectin levels are positively associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 567959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzberg, H.; Heymsfield, S.B. New insights into the regulation of leptin gene expression. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1013–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Cuenca, S.; Monjo, M.; Proenza, A.M.; Roca, P. Depot differences in steroid receptor expression in adipose tissue: Possible role of the local steroid milieu. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 288, E200–E207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasanthakumar, A.; Chisanga, D.; Blume, J.; Gloury, R.; Britt, K.; Henstridge, D.C.; Zhan, Y.; Torres, S.V.; Liene, S.; Collins, N.; et al. Sex-specific adipose tissue imprinting of regulatory t cells. Nature 2020, 579, 581–585, Erratum in Nature 2020, 579, 581–585.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Kastin, A.J. Adipokines and the blood-brain barrier. Peptides 2007, 28, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhea, E.M.; Salameh, T.S.; Logsdon, A.F.; Hanson, A.J.; Erickson, M.A.; Banks, W.A. Blood-brain barriers in obesity. AAPS J. 2017, 19, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Venegas, V.; Flores-Torres, R.P.; Rodriguez-Cortes, Y.M.; Rodriguez-Retana, D.; Ramirez-Carreto, R.J.; Concepcion-Carrillo, L.E.; Perez-Flores, L.J.; Alarcon-Aguilar, A.; Lopez-Diazguerrero, N.E.; Gomez-Gonzalez, B.; et al. The obese brain: Mechanisms of systemic and local inflammation, and interventions to reverse the cognitive deficit. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 798995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargrave, S.L.; Davidson, T.L.; Zheng, W.; Kinzig, K.P. Western diets induce blood-brain barrier leakage and alter spatial strategies in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 130, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Guo, M.; Zhang, W.; Lu, X.Y. Adiponectin stimulates proliferation of adult hippocampal neural stem/progenitor cells through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38mapk)/glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (gsk-3beta)/beta-catenin signaling cascade. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44913–44920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forny-Germano, L.; De Felice, F.G.; Vieira, M. The role of leptin and adiponectin in obesity-associated cognitive decline and alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Christie, B.R.; van Praag, H.; Lin, K.; Siu, P.M.; Xu, A.; So, K.F.; Yau, S.Y. Adiporon treatment induces a dose-dependent response in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calio, M.L.; Mosini, A.C.; Marinho, D.S.; Salles, G.N.; Massinhani, F.H.; Ko, G.M.; Porcionatto, M.A. Leptin enhances adult neurogenesis and reduces pathological features in a transgenic mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 148, 105219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.X.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.C.; Chen, A.D.; Gao, L.P.; Yin, J.; Jing, Y.H. High-fat diet increases amylin accumulation in the hippocampus and accelerates brain aging in hiapp transgenic mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boitard, C.; Etchamendy, N.; Sauvant, J.; Aubert, A.; Tronel, S.; Marighetto, A.; Laye, S.; Ferreira, G. Juvenile, but not adult exposure to high-fat diet impairs relational memory and hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 2095–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robison, L.S.; Albert, N.M.; Camargo, L.A.; Anderson, B.M.; Salinero, A.E.; Riccio, D.A.; Abi-Ghanem, C.; Gannon, O.J.; Zuloaga, K.L. High-fat diet-induced obesity causes sex-specific deficits in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. eNeuro 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pousti, F.; Ahmadi, R.; Mirahmadi, F.; Hosseinmardi, N.; Rohampour, K. Adiponectin modulates synaptic plasticity in hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 662, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J.; Pinky, P.D.; Smith, W.D.; Bhattacharya, D.; Chauhan, A.; Govindarajulu, M.; Hong, H.; Dhanasekaran, M.; Judd, R.; Amin, R.H.; et al. Adiponectin knockout mice display cognitive and synaptic deficits. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Solovyova, N.; Irving, A. Leptin and its role in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006, 45, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardi, M.; Spinelli, M.; Scala, F.; Mattera, A.; Fusco, S.; D’Ascenzo, M.; Grassi, C. Loss of leptin-induced modulation of hippocampal synaptic trasmission and signal transduction in high-fat diet-fed mice. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erion, J.R.; Wosiski-Kuhn, M.; Dey, A.; Hao, S.; Davis, C.L.; Pollock, N.K.; Stranahan, A.M. Obesity elicits interleukin 1-mediated deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 2618–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranahan, A.M. Visceral adiposity, inflammation, and hippocampal function in obesity. Neuropharmacology 2022, 205, 108920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A. The evolving obesity challenge: Targeting the vagus nerve and the inflammatory reflex in the response. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 222, 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo Boleti, A.P.; de Oliveira Flores, T.M.; Moreno, S.E.; Anjos, L.D.; Mortari, M.R.; Migliolo, L. Neuroinflammation: An overview of neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases and of biotechnological studies. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 136, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, C.M.; Hofmeister, J.J.; Nixon, J.P.; Butterick, T.A. High fat diet increases cognitive decline and neuroinflammation in a model of orexin loss. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2019, 157, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleti, A.P.d.A.; Cardoso, P.H.d.O.; Frihling, B.E.F.; Silva, P.S.E.; de Moraes, L.F.R.N.; Migliolo, L. Adipose tissue, systematic inflammation, and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.S.; Lin, C.M.; Chang, J.F.; Wu, C.S.; Sia, K.C.; Lee, I.T.; Huang, K.Y.; Lin, W.N. Participation of nadph oxidase-related reactive oxygen species in leptin-promoted pulmonary inflammation: Regulation of cpla2alpha and cox-2 expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L.O.; Gaspar, J.M. Obesity-induced brain neuroinflammatory and mitochondrial changes. Metabolites 2023, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.H.; Yau, S.Y. From obesity to hippocampal neurodegeneration: Pathogenesis and non-pharmacological interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.D.; Pistell, P.J.; Ingram, D.K.; Johnson, W.D.; Liu, Y.; Fernandez-Kim, S.O.; White, C.L.; Purpera, M.N.; Uranga, R.M.; Bruce-Keller, A.J.; et al. High fat diet increases hippocampal oxidative stress and cognitive impairment in aged mice: Implications for decreased nrf2 signaling. J. Neurochem. 2010, 114, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Wan, R.; Yang, J.L.; Kamimura, N.; Son, T.G.; Ouyang, X.; Luo, Y.; Okun, E.; Mattson, M.P. Involvement of PGC-1α in the formation and maintenance of neuronal dendritic spines. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwabu, M.; Yamauchi, T.; Okada-Iwabu, M.; Sato, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Funata, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Namiki, S.; Nakayama, R.; Tabata, M.; et al. Adiponectin and adipor1 regulate PGC-1α and mitochondria by Ca2+ and AMPK/SIRT1. Nature 2010, 464, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Adipokine | Pain | Cognition |

|---|---|---|

| Leptin | Pro-nociceptive: - ↑ Spinal NMDAR → neuropathic pain - Activates macrophages to release MMP-9/iNOS → hyperalgesia - ↑ Serum leptin correlates with chronic pain | Biphasic regulation: - Physiological: Promotes hippocampal neurogenesis & synaptic plasticity (via PI3K/AKT) - Pathological (obesity): Induces neuroinflammation → cognitive impairment |

| Adiponectin | Analgesic: - Intrathecal injection inhibits inflammatory hyperalgesia - Inhibits TRPV1/p38 MAPK → alleviates neuropathic pain | Neuroprotective: - Activates p38 MAPK/GSK-3β/β-catenin → hippocampal neurogenesis - ↓ Aβ aggregation - Low doses improve cognition; high doses suppress neurogenesis |

| Resistin | Pro-nociceptive: - Stimulates macrophages to release TNF-α/IL-1β → peripheral hyperalgesia - ↑ Synovial fluid levels correlate with pain severity in OA | Impairs cognition: - Promotes neuroinflammation via microglial NF-κB activation - Exacerbates related brain inflammation |

| NGF | Pro-nociceptive: - Directly induces peripheral/CNS hyperalgesia - TNF-α ↑ adipocyte NGF→ pain exacerbation | Biphasic regulation: - Modulates synaptic plasticity (indirect evidence) - Impaired BBB transport in obesity → cognitive decline |

| Inflammatory Cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α) | Pro-nociceptive: - Sensitize nociceptors, sustain chronic pain | Impair cognition: - IL-1β disrupts hippocampal synaptic plasticity - Excessive TNF-α disrupts synaptic homeostasis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, K.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; He, Z.; Xiang, H. Adipose Tissue and Central Nervous System Crosstalk: Roles in Pain and Cognitive Dysfunction. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010054

Li J, Li Z, Chen K, Wu Y, Yang X, He Z, Xiang H. Adipose Tissue and Central Nervous System Crosstalk: Roles in Pain and Cognitive Dysfunction. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Juan, Zhixiao Li, Kun Chen, Yanqiong Wu, Xuesong Yang, Zhigang He, and Hongbing Xiang. 2026. "Adipose Tissue and Central Nervous System Crosstalk: Roles in Pain and Cognitive Dysfunction" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010054

APA StyleLi, J., Li, Z., Chen, K., Wu, Y., Yang, X., He, Z., & Xiang, H. (2026). Adipose Tissue and Central Nervous System Crosstalk: Roles in Pain and Cognitive Dysfunction. Biomedicines, 14(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010054