Improved Iron Uptake and Metabolism Through Combined Heme and Non-Heme Iron Supplementation: An In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Agent Preparation

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Experimental Protocol

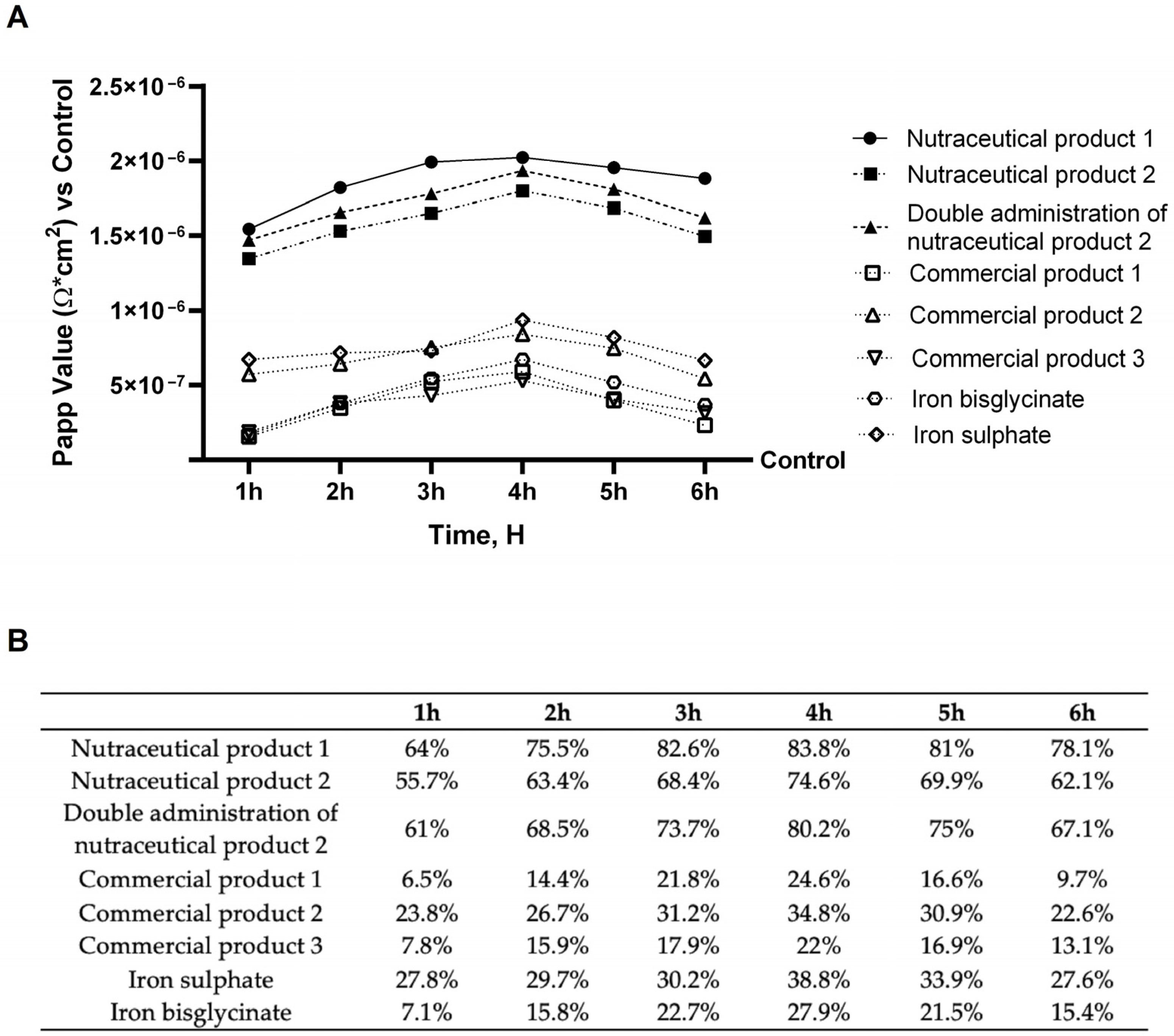

2.4. In Vitro Intestinal Barrier Model

- dQ: amount of substance transported (nmol or μg);

- dt: incubation time (s);

- m0: amount of substrate applied to the donor compartment (nmol or μg);

- A: Transwell® membrane surface area (cm2);

- V Donor: volume of the donor compartment (cm3).

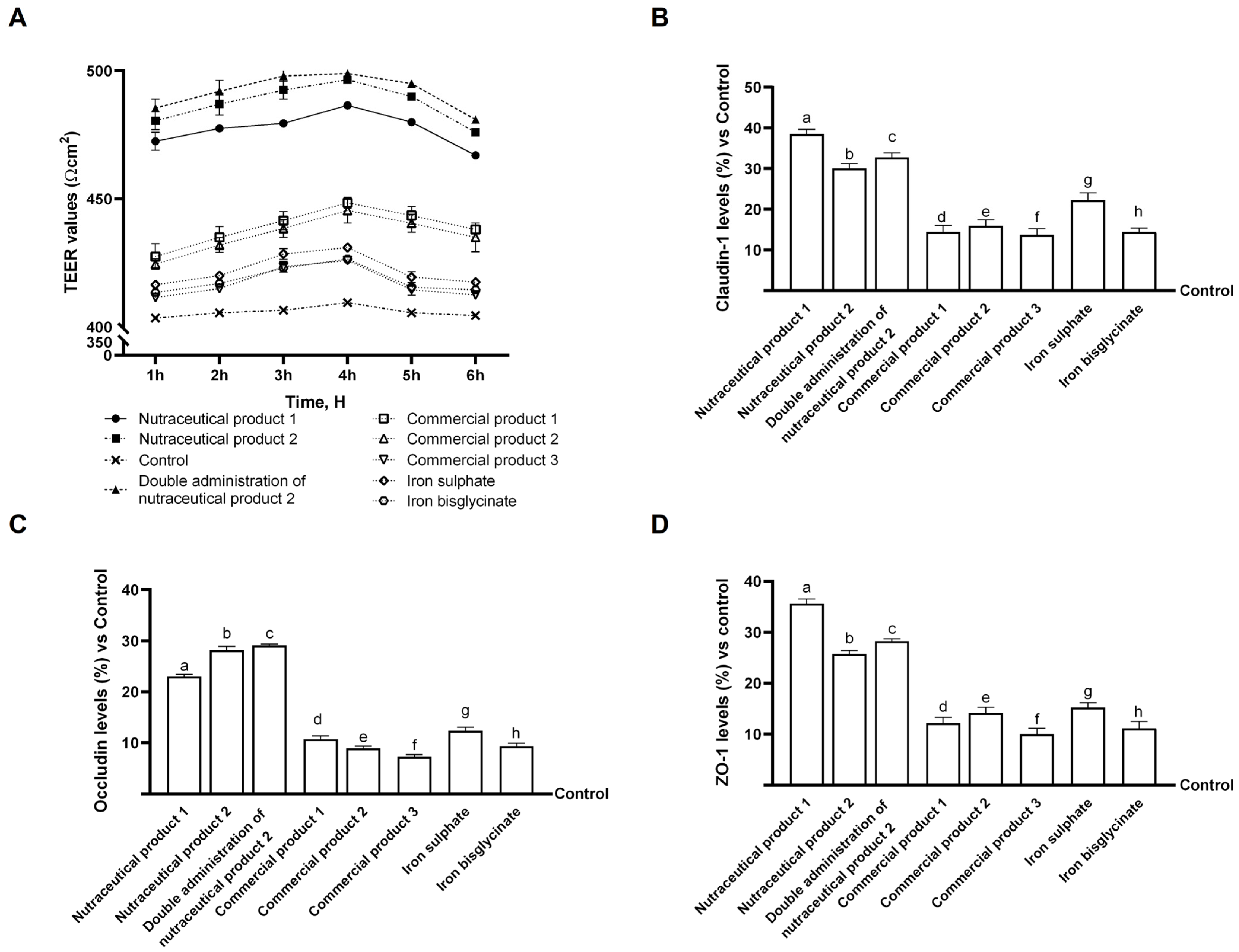

2.5. Tight Junction (TJ) Analysis

2.6. Iron Quantification Assay

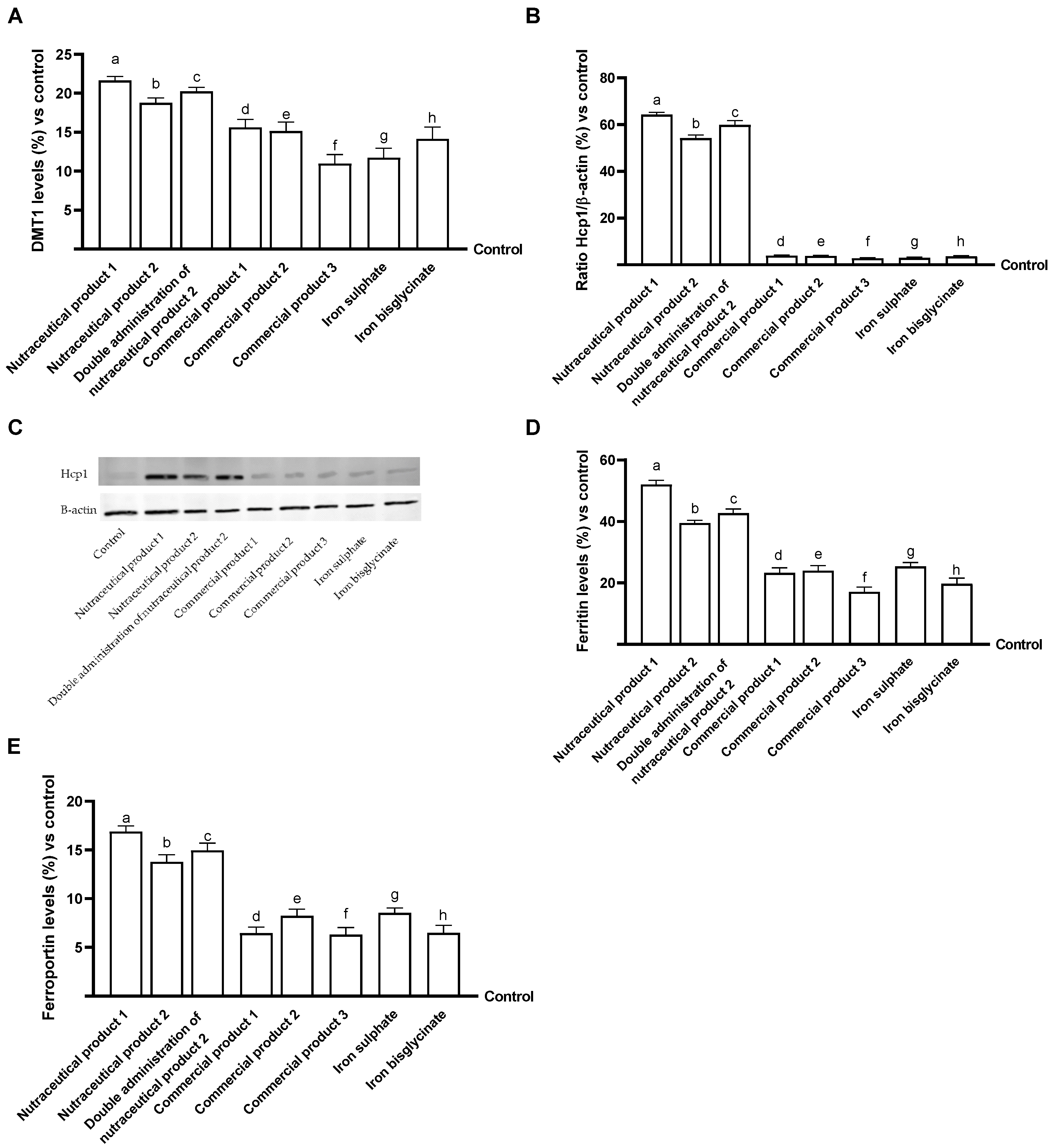

2.7. DMT1 ELISA Kit

2.8. Western Blot

2.9. Ferritin ELISA Kit

2.10. Ferroportin ELISA Kit

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Examination of Intestinal Effects Using Intestinal Barrier Model to Investigate Integrity and Absorption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | One-way analysis of variance |

| ATCC | American type culture collection |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium |

| DMEM-Adv | DMEM advance |

| DMT1 | Divalent metal transporter 1 |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FBS | Foetal bovine serum |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HCP-1 | Heme carrier protein-1 |

| TEER | Trans-epithelial electrical resistance |

| TJ | Tight junction |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ZO-1 | Zonula Occludens-1 |

References

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, E.; Marley, A.; Samaan, M.A.; Brookes, M.J. Iron Deficiency Anaemia: Pathophysiology, Assessment, Practical Management. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2022, 9, e000759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasricha, S.-R.; Tye-Din, J.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Swinkels, D.W. Iron deficiency. Lancet 2021, 397, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedfie, S.; Getawa, S.; Melku, M. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Iron Deficiency and Iron Deficiency Anemia Among Under-5 Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2022, 9, 2333794X221110860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.S.; Shah, A.; Stanworth, S.J.; Frise, C.J.; Spiby, H.; Lax, S.J.; Murray, J.; Klein, A.A. The effect of iron deficiency and anaemia on women’s health. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharati, S.; Pal, M.; Chakrabarty, S.; Bharati, P. Socioeconomic determinants of iron-deficiency anemia among children aged 6 to 59 months in India. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015, 27, NP1432–NP1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Santini, V.; Braxs, C.; Shander, A. Iron Metabolism and Iron Deficiency Anemia in Women. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 118, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayal, A.; Kaur, J.; Sadeghi, P.; Maitta, R.W. Molecular Mechanisms of Iron Metabolism and Overload. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Y.; Patel, D.; Khan, N. Iron deficiency anemia in IBD: An overlooked comorbidity. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 15, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustarah, F.; Daley, S.F. Dietary Iron. In StatPearls; Ineligible Companies: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Piskin, E.; Cianciosi, D.; Gulec, S.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. Iron absorption: Factors, limitations, and Improvement methods. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 20441–20456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catapano, A.; Cimmino, F.; Petrella, L.; Pizzella, A.; D’Angelo, M.; Ambrosio, K.; Marino, F.; Sabbatini, A.; Petrelli, M.; Paolini, B.; et al. Iron metabolism and ferroptosis in health and diseases: The crucial role of mitochondria in metabolically active tissues. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2025, 140, 109888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saboor, M.; Zehra, A.; Hamali, H.; Mobarki, A. Revisiting Iron Metabolism, Iron Homeostasis and Iron Deficiency Anemia. Clin. Lab. 2021, 67, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgalaboni, K.; Phoswa, W.N. Cross-Link between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Mini-Review. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2022, 45, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.F. The Regulation of Iron Absorption and Homeostasis. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2016, 37, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, S.; Babitt, J.L. Overview of Iron Metabolism in Health and Disease. Hemodial. Int. 2017, 21, S6–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairz, M.; Theurl, I.; Swirski, F.K.; Weiss, G. “Pumping Iron”—How Macrophages Handle Iron at the Systemic, Microenvironmental, and Cellular Levels. Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2017, 469, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, Y.Z. Hepcidin-ferroportin axis in health and disease. Vitam. Horm. 2019, 110, 17–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, P.J. Regulation of Iron Metabolism by Hepcidin under Conditions of Inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18975–18983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accelerating Anaemia Reduction: A Comprehensive Framework for Action. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240074033 (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Gallo Ruelas, M.; Alvarado-Gamarra, G.; Aramburu, A.; Dolores-Maldonado, G.; Cueva, K.; Rojas-Limache, G.; Diaz-Parra, C.D.P.; Lanata, C.F. A comparative analysis of heme vs. non-heme iron administration: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 64, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonuccelli, O.; Gogna, A.; Mitola, S.; Abate, G.; Ferrari, F.; Bertagna, F.; De Francesco, M.A.; Monti, E.; Bresciani, R.; Biasiotto, G. Enterolignans Improve the Expression of Iron-Related Genes in a Cellular Model of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uberti, F.; Trotta, F.; Pagliaro, P.; Bisericaru, D.M.; Cavalli, R.; Ferrari, S.; Penna, C.; Matencio, A. Developing New Cyclodextrin-Based Nanosponges Complexes to Improve Vitamin D Absorption in an In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fda.Gov. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/117974/download (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Ema.Eu. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-m9-biopharmaceutics-classification-system-based-biowaivers-step-2b-first-version_en.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Guha, S.; Alvarez, S.; Majumder, K. Transport of Dietary Anti-Inflammatory Peptide, γ-Glutamyl Valine (γ-EV), across the Intestinal Caco-2 Monolayer. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubatsch, I.; Ragnarsson, E.G.E.; Artursson, P. Determination of drug permeability and prediction of drug absorption in Caco-2 monolayers. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsanuto, V.; Galla, R.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. A New Palmitoylethanolamide form Combined with Antioxidant Molecules to Improve Its Effectivess on Neuronal Aging. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galla, R.; Ruga, S.; Aprile, S.; Ferrari, S.; Brovero, A.; Grosa, G.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. New Hyaluronic Acid from Plant Origin to Improve Joint Protection—An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberti, F.; Morsanuto, V.; Ghirlanda, S.; Molinari, C. Iron Absorption from Three Commercially Available Supplements in Gastrointestinal Cell Lines. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, T.; Chen, C.; Kang, Y.J. Copper uptake by DMT1: A compensatory mechanism for CTR1 deficiency in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Metallomics 2015, 7, 1285–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allden, S.J.; Ogger, P.P.; Ghai, P.; McErlean, P.; Hewitt, R.; Toshner, R.; Walker, S.A.; Saunders, P.; Kingston, S.; Molyneaux, P.L.; et al. The Transferrin Receptor CD71 Delineates Functionally Distinct Airway Macrophage Subsets during Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Jiang, S.; Yang, C.; Yang, S.; He, B.; Ma, W.; Zhao, R. Long-Term Dexamethasone Exposure Down-Regulates Hepatic TFR1 and Reduces Liver Iron Concentration in Rats. Nutrients 2017, 9, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, S.M.; Schulzke, J.D.; Fromm, M. Tight junction, selective permeability, and related diseases. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 36, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.L. Iron biology in immune function, muscle metabolism and neuronal functioning. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 568S–579S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugan, C.; Peeling, P.; Burden, R.; Richards, T. Efficacy of Iron Supplementation on Physical Capacity in Non-Anaemic Iron-Deficient Individuals: Protocol for an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voltarelli, V.A.; Alves de Souza, R.W.; Miyauchi, K.; Hauser, C.J.; Otterbein, L.E. Heme: The Lord of the Iron Ring. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Lao, C.; Huang, C.; Xia, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z. Iron Overload Resulting from the Chronic Oral Administration of Ferric Citrate Impairs Intestinal Immune and Barrier in Mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, D.; Hewlings, S.; Madelyn-Adjei, A.; Ebersole, B. Dietary Heme Iron: A Review of Efficacy, Safety and Tolerability. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chang, Y.Z. Cellular Iron Metabolism and Regulation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1173, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa, H.; Ito, H.; Terasaki, M.; Matano, D.; Taninaka, A.; Shigekawa, H.; Matsui, H. Nitric oxide regulates the expression of heme carrier protein-1 via hypoxia inducible factor-1α stabilization. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Casal, M.N.; Pasricha, S.R.; Martinez, R.X.; Lopez-Perez, L.; Peña-Rosas, J.P. Serum or plasma ferritin concentration as an index of iron deficiency and overload. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 5, Cd011817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, D.; Wilkins, S.; Darshan, D.; Mirciov, C.; Dunn, L.; Anderson, G. Ferroportin Is Essential for Iron Absorption During Suckling, but Is Hyporesponsive to the Regulatory Hormone Hepcidin. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 3, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Parini, F.; Galla, R.; Mulè, S.; Musu, M.; Uberti, F. Improved Iron Uptake and Metabolism Through Combined Heme and Non-Heme Iron Supplementation: An In Vitro Study. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010043

Parini F, Galla R, Mulè S, Musu M, Uberti F. Improved Iron Uptake and Metabolism Through Combined Heme and Non-Heme Iron Supplementation: An In Vitro Study. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleParini, Francesca, Rebecca Galla, Simone Mulè, Matteo Musu, and Francesca Uberti. 2026. "Improved Iron Uptake and Metabolism Through Combined Heme and Non-Heme Iron Supplementation: An In Vitro Study" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010043

APA StyleParini, F., Galla, R., Mulè, S., Musu, M., & Uberti, F. (2026). Improved Iron Uptake and Metabolism Through Combined Heme and Non-Heme Iron Supplementation: An In Vitro Study. Biomedicines, 14(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010043