Effects of Dietary Interventions on Nutritional Status in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

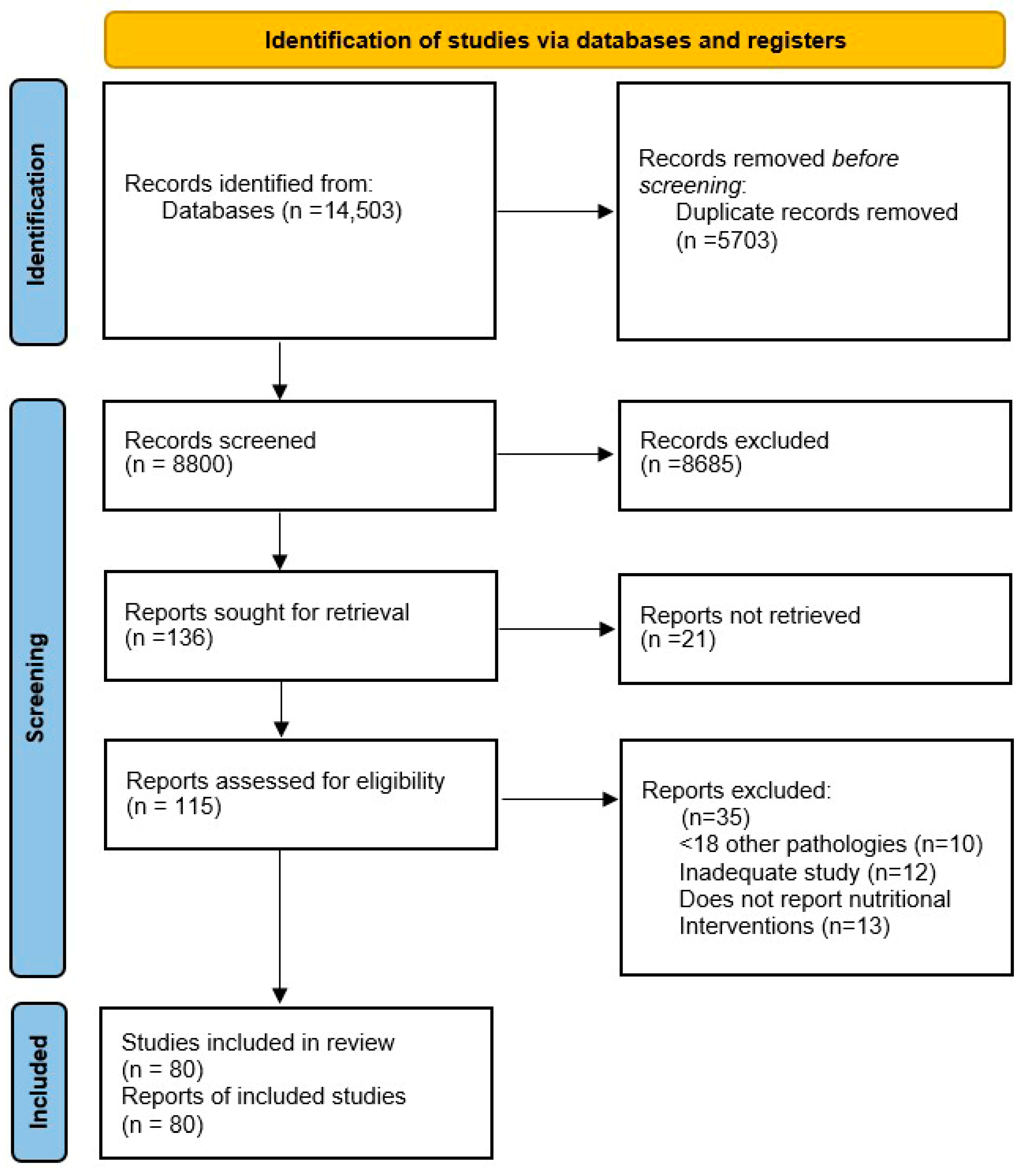

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Assessment of Risk of Bias

3. Results and Discussions

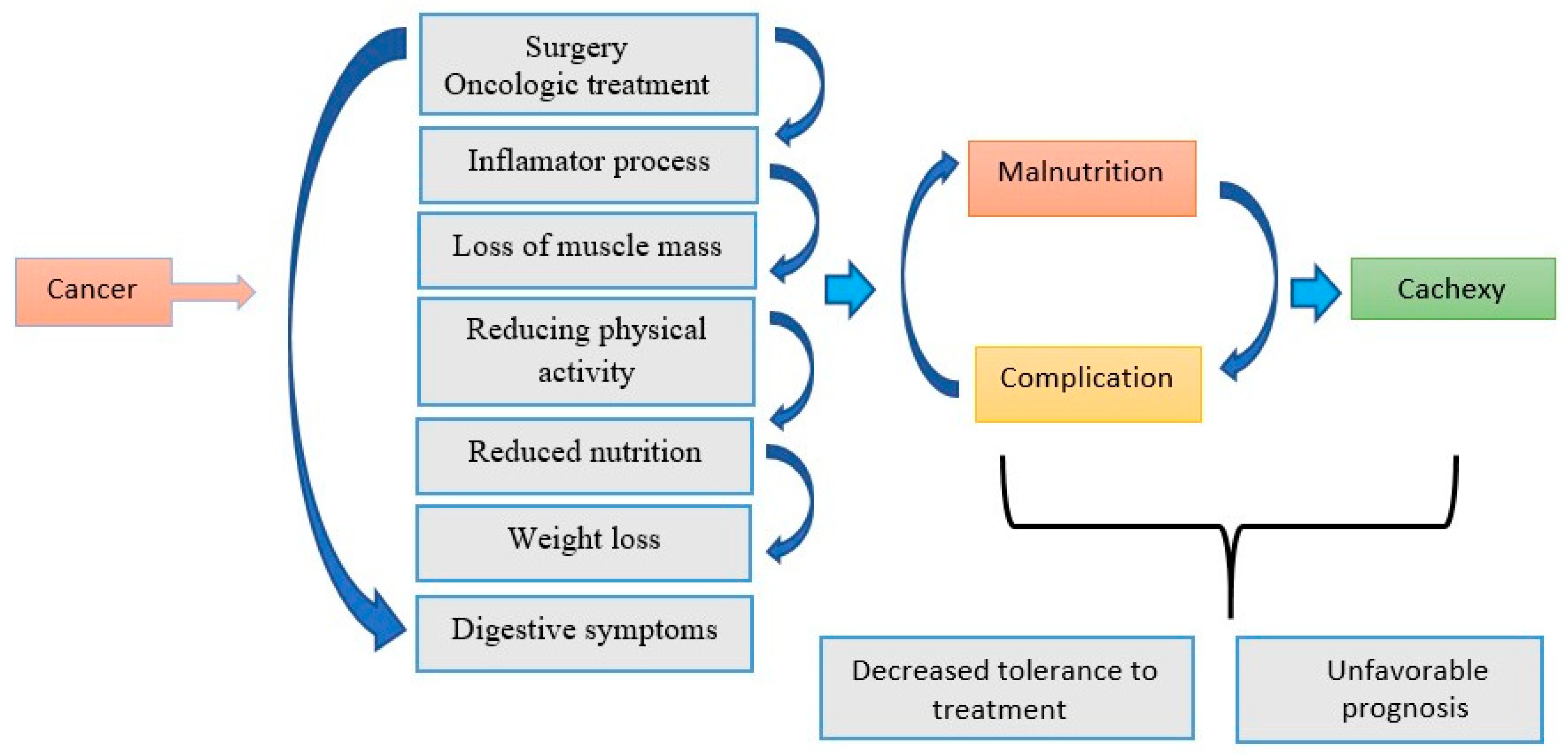

3.1. The Role of Inflammation and Nutritional Status in the Evolution of Oncological Patients

3.1.1. The Impact of Malnutrition on Prognosis

3.1.2. Systemic Inflammation and Muscle Loss

3.1.3. Changes in Dietary Intake and the Effects of Oncological Therapy

3.2. Cross-Sectional and Cohort Observational Studies That Assessed the Prevalence of Malnutrition, Risk Factors and Survival of Oncological Patients

3.2.1. Malnutrition or Poor Diet in Patients with GI Cancer

| First Author/Year | Type of Study | Study Population (N) | Cancer Type | Nutritional Parameter Evaluated | Main Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakazono, 2021 | Comparative observational Study | 150 | Cancer Gastric | Post-gastrectomy food intake | Total gastrectomy is associated with significantly greater food losses compared to other types of gastric resections, having direct implications on postoperative nutritional status. | [5] |

| Rasschaert, 2024 | Prospective observational cross-sectional | 328 | Diverse Cancers | Malnutrition screening | Prevalence of malnutrition and cachexia. | [8] |

| Amezaga J, 2018 | Transverse | 151 | Various cancers | Assessment of self-reported chemosensory changes in patients undergoing chemotherapy | Changes in taste and smell are common side effects in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatments. | [29] |

| Durán Poveda, 2023 | Prospective, observational, multicenter | 469 | Cancer GI | MUST, PG-SGA | 40% of patients are at risk of malnutrition and increased mortality. | [19] |

| Pressoir, 2010 | Cross-sectional observational, prospective multicenter | 1545 | Various cancers (predominantly digestive) | IMC | Prevalence of malnutrition, correlation with length of hospitalization and mortality. | [33] |

| Hébuterne, 2014 | Transverse | 1903 | Digestive Cancers | IMC, weight loss | 39% of patients present with malnutrition. | [38] |

| Prado, 2008 | Transverse | 2115 | Digestive/GI cancers | Muscle mass (CT) | Sarcopenia is associated with reduced survival. | [37] |

| de Pinho, 2019 | Transverse | 4783 | Various cancers | Increased risk of malnutrition | Prevalence and risk factors of malnutrition in hospitalized cancer patients. | [39] |

| Flynn, 2018 | Transverse | 140 | Various cancers | Implementation of nutritional screening tools | Managing cancer cachexia | [40] |

| First Author, Year | Type of Study | Population (N) | Cancer Type | Follow-Up Period | Nutritional Parameter Evaluated | Main Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miyamoto, 2015 | Observational cohort | 215 | Inoperable CCR | 8 years | Weight loss, skeletal muscle analysis | Loss of muscle mass has a negative prognosis. | [41] |

| Oh, R.K, 2020 | Prospective cohort | 423 | Colorectal | 4 years | Muscle mass, CT scan | Sarcopenia has been associated with postoperative complications after laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer. | [42] |

| Boulahssass, 2019 | Observational cohort | 3140 | Various digestive cancers | 6 years | Malnutrition status | Poor diets correlated with decreased survival. | [44] |

| Choi M.H, 2018 | Retrospective cohort | 188 | Advanced rectal cancer | 52 months | Nutritional status, sarcopenia | Sarcopenia associated with decreased survival. | [46] |

| Fettig A, 2025 | Observational cohort | 2000 | Various types of cancer | 10 years | Adverse effects of treatment, nutrition combined with exercise and relaxation | Patients demand more personalized information on diet and nutritional support, analysis suggests communication gaps. | [47] |

| Martin, 2015 | Observational cohort | 8160 | Various types of cancer | 2 years | Causes of death | Weight loss is unclear. | [48] |

| Feriolli, 2012 | Observational cohort, prospective | 162 | Operable gastrointestinal cancer | 5–6 weeks after surgery | Monitoring physical activity at different stages | Physical activity correlates with disease stage and quality of life. | [49] |

| Bozzetti, 2014 | Observational cohort | 414 | Incurable cachexia | 6 years | Parenteral nutrition | The role of parenteral nutrition is controversial. | [50] |

| Velasquez, 2023 | Observational cohort | 68 | Various types of cancer | 6 months | Nutritional assessment | Complications of parenteral nutrition. | [51] |

| Jeannine Bachmann, 2008 | Observational cohort | 198 | Pancreatic cancer | 18 months | Massive loss of adipose tissue | Due to skeletal muscle loss, many cachexia patients develop pulmonary failure with dyspnea as a common symptom. | [52] |

3.2.2. The Relationship Between Nutritional Intervention and Patient Age

| Appearance | Young Patients | Elderly Patients | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein intake | 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day | 1.5 g/kg/day or more to prevent sarcopenia | [54,55] |

| Calories | Adequate according to weight and activity | Adequate, more careful monitoring for rapid weight loss | [25,55] |

| Supplements | ONS if dietary intake insufficient | ONS frequently recommended, possibly with anti-inflammatory nutrients (e.g., omega 3) | [25,45] |

| Food texture/consistency | Normal | Possibly adapted for dysphagia, dental problems or reduced digestion | [25] |

| Monitoring | Standard | More frequent: weight, muscle mass, nutritional laboratory | [25,54,55] |

3.2.3. Malnutrition and Nutritional Management in Patients with GI Cancer

3.2.4. Postoperative and Posttreatment Nutritional Management in Patients with GI Cancer

| First Author, Year | Type of Study | Population (N) | Cancer Type | Intervention | Follow-Up Period | Main Results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nett et al., 2022 | RCT | 62 | Diverse | Oral supplement + physical activity + personalized nutrition | 6 months | Improving nutritional status and quality of life | [64] |

| Gavazzi, 2016 | RCT | 79 | Upper GI, malnutrition | Home enteral nutrition vs. control | 3 months | Home enteral nutrition improved weight and quality of life | [70] |

| Wang et al., 2025 | RCT | 88 | Colorectal | Individualized nutrition postoperative | 12 months | Improving both chemotherapy tolerance and quality of life | [63] |

| Basch, 2017 | RCT | 766 | Various types of cancer | Reported parameters, nutritional intervention | 4 ani | Results on the link between reported symptoms and survival | [71] |

| Ryan, 2009 | RCT | 53 | Esophagus | Enteral nutrition+ EPA | 5 days preoperative, 21 days postoperative | Early supplementation of enteral nutrition (EN) with eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) was associated with superior preservation of lean muscle mass post esophagectomy compared with standard enteral nutrition | [72] |

| First Author, Year | Type of Study | Number of Studies Included | Type of Cancer | Analyzed Intervention | The Main Conclusion | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minhajat, 2023 | Systematic review | 1424 | Colorectal Cancer | Diet and nutritional status, the impact of BMI | Nutritional deficiency is associated with a poor prognosis. | [34] |

| de Vries-ten Have, 2025 | Systematic review | 21 | CRC survivors | Determinants of healthy behaviors (diet, activity) | Identifies barriers and facilitators for adopting a healthy lifestyle in CRC survivors. | [79] |

| Sadeghi, 2021 | Systematic review | 5 | Upper GI cancers | Nutrition interventions + exercises, movement | Combined interventions show benefits on nutritional status and some functional elements, but RCT data are limited and heterogeneous. | [58] |

| Zou, Q., 2024 | Meta-analysis | 12 | Gastrointestinal cancers (surgery) | Perioperative nutritional support | Perioperative support improves some postoperative outcomes; varies by outcome. | [80] |

| Abebe, 2025 | Systematic review | 28 | Gastro-digestive cancers | Dietary patterns by principal component analysis and reduced rank regression | Certain dietary patterns are associated with different risk/mortality; moderate conclusions. | [24] |

| Bouras, 2022 | Umbrella review | 49 | Gastric cancer | Umbrella analysis | Mixed results; some consistent evidence for certain dietary exposures. | [83] |

| Moazzen, 2021 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 44 | Colorectal cancer | The role of diet quality on colorectal cancer risk | It would be recommended that general dietary advice could be provided in clinical settings. | [84] |

| Veettil, 2021 | Review and meta-analysis | 45 | Colorectal cancer | Dietary plan rich in protein, fiber | Synthesizes evidence and degree of consistency; some robust associations. | [85] |

| Cortés-Aguilar, 2024 | Review and meta-analysis | 21 | Metastatic colorectal cancer | Screening tools | MUST is a precision instrument. | [82] |

| Spei, 2023 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 19 | Cancer survivors | Dietary pattern, post-diagnosis | Certain post-diagnosis patterns associated with mortality; moderate evidence. | [86] |

| Sealy MJ, 2016 | Systematic review | 160 | Cancer patients | Malnutrition evaluation | Thirty-seven methods for assessing malnutrition were identified, but none have acceptable content validity, compared to a construct based on the ESPEN and ASPEN definitions of malnutrition. | [87] |

| Keshavjee S., 2025 | Systematic review | 27 | Post-operative colorectal cancer | The impact of sarcopenia on post-surgical condition | Preoperative sarcopenia increases the risk of complications, length of hospital stay, and postoperative mortality. | [61] |

| Tsilidis, 2024 | Systematic review | 124 | Post-diagnosis colorectal cancer | Obesity, physical activity, diet, supplements | Moderately vigorous physical activity and a healthy diet are correlated with improved prognosis; adiposity and sedentary behavior correlate with a poor prognosis. | [88] |

| Chan, 2024 | Systematic review | 69 | Colorectal cancer | Post-diagnosis dietary factors and supplements | Diets high in fiber, whole grains, fruits/vegetables, and moderate dairy intake are associated with better survival; red meat, alcohol, and Ca/Vit D supplements show mixed evidence. | [89] |

| Fretwell, 2025 | Systematic review | 28 | Colorectal cancer | The role of diet after diagnosis | Evidence on post-diagnosis diet remains insufficient; positive trends for Mediterranean-type and high-fiber diets. | [90] |

| Aya V, 2021 | Systematic review | 17 | Active patients | Physical activity and gut microbiota | Studies show subtle changes in the diversity and abundance of certain bacteria in active individuals; recommendations for more standardized measurements. | [91] |

| Dewiasty, 2024 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 15 | Institutionalized elderly people in Indonesia | Prevalence of malnutrition, nutritional intake | The prevalence of malnutrition varies widely: 6.5–48.3% (hospitals) and 3.2–61.0% (other institutions); frequent protein, Ca, Vit D deficiencies were highlighted. | [92] |

| Hosseini, 2025 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 19 | Cancer patients (various) | Prevalence of severe malnutrition | Severe malnutrition. | [93] |

| Inciong, 2020 | Systematic review | 92 | Hospitalized patients in Northeast and Southeast Asia | Prevalence of malnutrition, consequences | Poor nutritional status is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and increased healthcare costs. Further research is needed. | [94] |

| Keesari, 2024 | Systematic review | 8 | Patients with prediabetes and increased risk of colorectal cancer | Associated metabolic risk | The probability of developing CRC is 16% higher in patients with prediabetes. | [95] |

3.3. Dietary Patterns Related to Prevention and Survival

3.3.1. Dietary Patterns and GI Cancer Prevention

3.3.2. Dietary Patterns for Survival in Patients with GI Cancer

3.4. Methods of Nutrient Administration

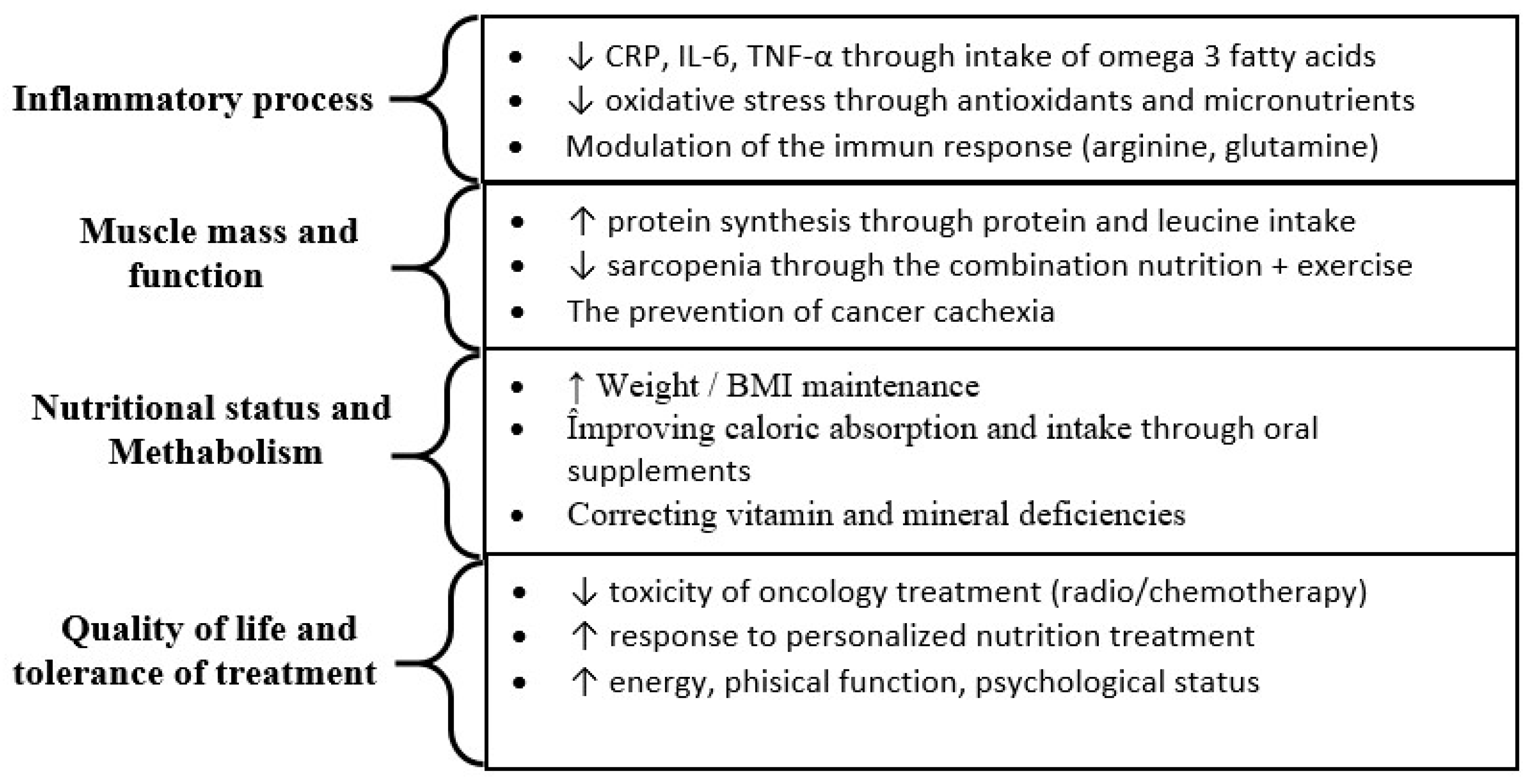

3.5. General Observations of the Analysis

3.6. Recommendations for Future Research

3.7. Strengths of This Systematic Review

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, L.T.; Dang, A.K.; Duong, P.T.; Phan, H.B.T.; Pham, C.T.T.; Nguyen, A.T.L.; Le, H.T. Nutrition intervention is beneficial to the quality of life of patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemotherapy in Vietnam. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 1668–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otvos, J.D.; Shalaurova, I.; May, H.T.; Muhlestein, J.B.; Wilkins, J.T.; McGarrah, R.W.; Kraus, W.E. Multimarkers of metabolic malnutrition and inflammation and their association with mortality risk in cardiac catheterisation patients: A prospective, longitudinal, observational, cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2023, 4, e72–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michońska, I.; Polak-Szczybyło, E.; Sokal, A.; Jarmakiewicz-Czaja, S.; Stępień, A.E.; Dereń, K. Nutritional issues faced by patients with intestinal stoma: A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Ueno, T.; Yoshida, N.; Akutsu, Y.; Takeuchi, H.; Baba, H.; Matsubara, H.; Kitagawa, Y.; Yoshida, K. The effect of an elemental diet on oral mucositis of esophageal cancer patients treated with DCF chemotherapy: A multi-center prospective feasibility study (EPOC study). Esophagus 2018, 15, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazono, M.; Aoyama, T.; Hayashi, T.; Hara, K.; Segami, K.; Shimoda, Y.; Nagasawa, S.; Kumazu, Y.; Yamada, T.; Tamagawa, H.; et al. Comparison of the dietary intake loss between total and distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Vivo 2021, 35, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, M.; White, K.; Brown, C.; Bauer, J.D. Nutritional status and skeletal muscle status in patients with head and neck cancer: Impact on outcomes. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 2187–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furbetta, N.; Comandatore, A.; Gianardi, D.; Palmeri, M.; Di Franco, G.; Guadagni, S.; Caprili, G.; Bianchini, M.; Fatucchi, L.M.; Picchi, M.; et al. Perioperative nutritional aspects in total pancreatectomy: A comprehensive review of the literature. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasschaert, M.; Vandecandelaere, P.; Marechal, S.; D’hondt, R.; Vulsteke, C.; Mailleux, M.; De Roock, W.; Van Erps, J.; Himpe, U.; De Man, M. Malnutrition prevalence in cancer patients in Belgium: The ONCOCARE study. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, G.; Perry, R.; Andersen, H.K.; Atkinson, C.; Penfold, C.; Lewis, S.J.; Ness, A.R.; Thomas, S. Early enteral nutrition within 24 hours of lower gastrointestinal surgery versus later commencement for length of hospital stay and postoperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, CD004080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, H.M.; Forte, M.L.; Abdi, H.I.; Brandt, S.; Claussen, A.M.; Wilt, T.; Klein, M.; Ester, E.; Landsteiner, A.; Shaukut, A.; et al. Nutrition as prevention for improved cancer health outcomes: A systematic literature review. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2023, 7, pkad035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravasco, P. Nutrition in cancer patients. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Chong, F.; Huo, Z.; Li, N.; Liu, J.; Xu, H. GLIM-defined malnutrition and overall survival in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2023, 47, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.-G.; Choi, J.-Y.; Yoo, H.-J.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, K.-I. Impact of malnutrition evaluated by the mini nutritional assessment on the prognosis of acute hospitalized older adults. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1046985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Larsson, S.C. Epidemiology of sarcopenia: Prevalence, risk factors, and consequences. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, T.S.; Laird, B.J.; Balstad, T.R.; Bye, A.; Stene, G.; Baracos, V.; Strasser, F.; Griffiths, G.; Maddocks, M.; Fallon, M.; et al. Cancer cachexia: Rationale for the MENAC (Multimodal—Exercise, Nutrition and Anti-inflammatory medication for Cachexia) trial. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2018, 8, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navratilova, H.F.; Lanham-New, S.; Whetton, A.D.; Geifman, N. Associations of diet with health outcomes in the UK biobank: A systematic review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markozannes, G.; Cividini, S.; Aune, D.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Kiss, S.; Balducci, K.; Vieira, R.; Cariolou, M.; Jayedi, A.; Greenwood, D.; et al. The role of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, diet, adiposity and body composition on health-related quality of life and cancer-related fatigue after diagnosis of colorectal cancer: A Global Cancer Update Programme (CUP Global) systematic literature review and meta-analysis. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104301. [Google Scholar]

- Poveda, M.D.; Suárez-de-la-Rica, A.; Minchot, E.C.; Bretón, J.O.; Pernaute, A.S.; Caravaca, G.R. The prevalence and impact of nutritional risk and malnutrition in gastrointestinal surgical oncology patients: A prospective, observational, multicenter, and exploratory study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, W.; Veronese, N.; Kelly, J.T.; Smith, L.; Hockey, M.; Collins, S.; Trakman, G.L.; Hoare, E.; Teasdale, S.B.; Wade, A. The dietary inflammatory index and human health: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Espin, C.; Agudo, A. The role of diet in prognosis among cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary patterns and diet interventions. Nutrients 2022, 14, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti, F. Suboptimal nutritional support in cancer patients gets excellent results. Reply to the Letter to the Editor:‘Nutritional support during the hospital stay reduces mortality in patients with different types of cancers: Secondary analysis of a prospective randomized trial’ by L. Bargetzi et al. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1304–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaloni, M.; Caccialanza, R.; Ravasco, P.; Carrato, A.; Kapala, A.; de van der Schueren, M.; Constantinides, D.; Backman, E.; Chuter, D.; Santangelo, C.; et al. The impact of nutrition on the lives of patients with digestive cancers: A position paper. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 7991–7996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abebe, Z.; Wassie, M.M.; Mekonnen, T.C.; Reynolds, A.C.; Melaku, Y.A. Difference in Gastrointestinal Cancer Risk and Mortality by Dietary Pattern Analysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e991–e1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Fearon, K.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimann, A.; Braga, M.; Carli, F.; Higashiguchi, T.; Hübner, M.; Klek, S.; Laviano, A.; Ljungqvist, O.; Lobo, D.N.; Martindale, R.; et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti, F.; Gianotti, L.; Braga, M.; Di Carlo, V.; Mariani, L. Postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients: The joint role of the nutritional status and the nutritional support. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 26, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirer, A. Malnutrition and cancer, diagnosis and treatment. Memo-Mag. Eur. Med. Oncol. 2021, 14, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amézaga, J.; Alfaro, B.; Ríos, Y.; Larraioz, A.; Ugartemendia, G.; Urruticoechea, A.; Tueros, I. Assessing taste and smell alterations in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy according to treatment. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 4077–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Birdsell, L.; MacDonald, N.; Reiman, T.; Clandinin, M.T.; McCargar, L.J.; Murphy, R.; Ghosh, S.; Sawyer, M.B.; Baracos, V.E. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menozzi, R.; Valoriani, F.; Ballarin, R.; Alemanno, L.; Vinciguerra, M.; Barbieri, R.; Costantini, R.C.; D’Amico, R.; Torricelli, P.; Pecchi, A. Impact of nutritional status on postoperative outcomes in cancer patients following elective pancreatic surgery. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrah, R.; Van Der Borch, C.; Kanbalian, M.; Jagoe, R.T. Defining barriers to implementation of nutritional advice in patients with cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressoir, M.; Desné, S.; Berchery, D.; Rossignol, G.; Poiree, B.; Meslier, M.; Traversier, S.; Vittot, M.; Simon, M.; Gekiere, J.; et al. Prevalence, risk factors and clinical implications of malnutrition in French Comprehensive Cancer Centres. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 966–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhajat, R.; Harjianti, T.; Rasyid, H.; Bukhari, A.; Islam, I.C.; Zainal, A.T.F.; Gunawan, A.M.A.K.; Ramadhan, A.C.; Hatta, H.; Syamsu Alam, N.I. Colorectal cancer patients’ outcome in correlation with dietary and nutritional status: A systematic review. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2281662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccialanza, R.; Pedrazzoli, P.; Cereda, E.; Gavazzi, C.; Pinto, C.; Paccagnella, A.; Beretta, G.D.; Nardi, M.; Laviano, A.; Zagonel, V. Nutritional support in cancer patients: A position paper from the Italian Society of Medical Oncology (AIOM) and the Italian Society of Artificial Nutrition and Metabolism (SINPE). J. Cancer 2016, 7, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, C.M.; Lieffers, J.R.; McCargar, L.J.; Reiman, T.; Sawyer, M.B.; Martin, L.; Baracos, V.E. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hébuterne, X.; Lemarié, E.; Michallet, M.; de Montreuil, C.B.; Schneider, S.M.; Goldwasser, F. Prevalence of malnutrition and current use of nutrition support in patients with cancer. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2014, 38, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pinho, N.B.; Martucci, R.B.; Rodrigues, V.D.; D’Almeida, C.A.; Thuler, L.C.S.; Saunders, C.; Jager-Wittenaar, H.; Peres, W.A.F. Malnutrition associated with nutrition impact symptoms and localization of the disease: Results of a multicentric research on oncological nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1274–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.; Barrett, M.; Sui, J.; Halpin, C.; Paz, G.; Walsh, D. Nutritional status and interventions in hospice: Physician assessment of cancer patients. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Baba, Y.; Sakamoto, Y.; Ohuchi, M.; Tokunaga, R.; Kurashige, J.; Hiyoshi, Y.; Iwagami, S.; Yoshida, N.; Watanabe, M.; et al. Negative impact of skeletal muscle loss after systemic chemotherapy in patients with unresectable colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, R.K.; Ko, H.M.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.S. Clinical impact of sarcopenia in patients with colon cancer undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2020, 99, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bye, A.; Sjøblom, B.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Grønberg, B.H.; Baracos, V.E.; Hjermstad, M.J.; Aass, N.; Bremnes, R.M.; Fløtten, Ø.; Jordhøy, M. Muscle mass and association to quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulahssass, R.; Gonfrier, S.; Champigny, N.; Lassalle, S.; François, E.; Hofman, P.; Guerin, O. The desire to better understand older adults with solid tumors to improve management: Assessment and guided interventions—The French PACA EST cohort experience. Cancers 2019, 11, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisdale, M.J. Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.H.; Oh, S.N.; Lee, I.K.; Oh, S.T.; Won, D.D. Sarcopenia is negatively associated with long-term outcomes in locally advanced rectal cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2018, 9, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettig, A.; Mathies, V.; Hübner, J. Nutrition in cancer patients: Analysis of the forum of women’ s self-help association against cancer. BMC Nutr. 2025, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Senesse, P.; Gioulbasanis, I.; Antoun, S.; Bozzetti, F.; Deans, C.; Strasser, F.; Thoresen, L.; Jagoe, R.T.; Chasen, M.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for the classification of cancer-associated weight loss. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriolli, E.; Skipworth, R.J.; Hendry, P.; Scott, A.; Stensteth, J.; Dahele, M.; Wall, L.; Greig, C.; Fallon, M.; Strasser, F.; et al. Physical activity monitoring: A responsive and meaningful patient-centered outcome for surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy? J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2012, 43, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti, F.; Santarpia, L.; Pironi, L.; Thul, P.; Klek, S.; Gavazzi, C.; Tinivella, M.; Joly, F.; Jonkers, C.; Baxter, J.; et al. The prognosis of incurable cachectic cancer patients on home parenteral nutrition: A multi-centre observational study with prospective follow-up of 414 patients. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, D.A.; Dhiman, A.; Brottman, C.; Eng, O.S.; Fenton, E.; Herlitz, J.; Lozano, E.; McDonald, E.; Reynolds, V.; Wall, E.; et al. Outcomes of parenteral nutrition in patients with advanced cancer and malignant bowel obstruction. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, J.; Ketterer, K.; Marsch, C.; Fechtner, K.; Krakowski-Roosen, H.; Büchler, M.W.; Friess, H.; Martignoni, M.E. Pancreatic cancerrelated cachexia: Influence on metabolism and correlation to weight loss and pulmonary function. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClelland, S., III; Andrews, J.Z.; Chaudhry, H.; Teckie, S.; Goenka, A. Prophylactic versus reactive gastrostomy tube placement in advanced head and neck cancer treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2018, 87, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, S.; Kokura, Y.; Momosaki, R.; Taketani, Y. Measures for identifying malnutrition in geriatric rehabilitation: A scoping review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, Z.; Loman, B.R. Nutrition Interventions in the Treatment of Gastrointestinal Symptoms during Cancer Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Cintoni, M.; Raoul, P.; Pozzo, C.; Strippoli, A.; Bria, E.; Tortora, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. Effects of nutritional interventions on nutritional status in patients with gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 38, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, F.; Mockler, D.; Guinan, E.M.; Hussey, J.; Doyle, S.L. The effectiveness of nutrition interventions combined with exercise in upper gastrointestinal cancers: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, T.; Yorke, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Kong, X.; Lam, K.K.W.; Liu, Q.; Yang, F.; Ho, K.Y. The relationship between nutritional status and prognosis in advanced gastrointestinal cancer patients in palliative care: A prospective cohort study. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzetti, F. Is there a place for nutrition in palliative care? Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 4069–4075. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavjee, S.; Mckechnie, T.; Shi, V.; Abbas, M.; Huang, E.; Amin, N.; Hong, D.; Eskicioglu, C. The impact of sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. Surg. 2025, 91, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, K.H.; Brown, J.C.; Irwin, M.L.; Robien, K.; Scott, J.M.; Berger, N.A.; Caan, B.; Cercek, A.; Crane, T.E.; Evans, S.R.; et al. Exercise and nutrition to improve cancer treatment-related outcomes (ENICTO). JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2025, 117, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xie, M.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Yin, C. Effect of Nutritional Intervention on Chemotherapy Tolerance and Quality of Life in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Postoperative Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Study. Nutr. Cancer 2025, 77, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nett, H.; Steegmann, J.; Tollkühn-Prott, B.; Hölzle, F.; Modabber, A. A prospective randomized comparative trial evaluating postoperative nutritional intervention in patients with oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiatt, R.A.; Clayton, M.F.; Collins, K.K.; Gold, H.T.; Laiyemo, A.O.; Truesdale, K.P.; Ritzwoller, D.P. The Pathways to Prevention program: Nutrition as prevention for improved cancer outcomes. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2023, 115, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wu, J.; Meng, L.; Zhu, B.; Wang, H.; Xin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cui, S.; Sun, Y.; Dong, L.; et al. Effects of early nutritional intervention on oral mucositis in patients with radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. QJM Int. J. Med. 2020, 113, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Spiro, A.; Ahern, R.; Emery, P.W. Oral nutritional interventions in malnourished patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereda, E.; Cappello, S.; Colombo, S.; Klersy, C.; Imarisio, I.; Turri, A.; Caraccia, M.; Borioli, V.; Monaco, T.; Benazzo, M.; et al. Nutritional counseling with or without systematic use of oral nutritional supplements in head and neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. 2018, 126, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, B.; Baker, A.L.; Wolfenden, L.; Wratten, C.; Bauer, J.; Beck, A.K.; McCarter, K.; Harrowfield, J.; Isenring, E.; Tang, C.; et al. Eating As Treatment (EAT): A stepped-wedge, randomized controlled trial of a health behavior change intervention provided by dietitians to improve nutrition in patients with head and neck cancer undergoing radiation therapy (TROG 12.03). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 103, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavazzi, C.; Colatruglio, S.; Valoriani, F.; Mazzaferro, V.; Sabbatini, A.; Biffi, R.; Mariani, L.; Miceli, R. Impact of home enteral nutrition in malnourished patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer: A multicentre randomised clinical trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2016, 64, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Dueck, A.C.; Scher, H.I.; Kris, M.G.; Hudis, C.; Schrag, D. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 2017, 318, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.M.; Reynolds, J.V.; Healy, L.; Byrne, M.; Moore, J.; Brannelly, N.; McHugh, A.; McCormack, D.; Flood, P. Enteral nutrition enriched with eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) preserves lean body mass following esophageal cancer surgery: Results of a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 2009, 249, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Sullivan, K.R.; Howe, C.L.; Kushi, L.H.; Caan, B.J.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Wang, Y.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 230–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hustad, K.S.; Koteng, L.H.; Urrizola, A.; Arends, J.; Bye, A.; Dajani, O.; Deliens, L.; Fallon, M.; Hjermstad, M.; Kohlen, M.; et al. Practical cancer nutrition, from guidelines to clinical practice: A digital solution to patient-centred care. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gliwska, E.; Guzek, D.; Przekop, Z.; Sobocki, J.; Głąbska, D. Quality of life of cancer patients receiving enteral nutrition: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGovern, J.; Dolan, R.D.; Skipworth, R.J.; Laird, B.J.; McMillan, D.C. Cancer cachexia: A nutritional or a systemic inflammatory syndrome? Br. J. Cancer 2022, 127, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, N.; Sullivan, E.S.; Kalliostra, M.; Laviano, A.; Wesseling, J. Nutrition care is an integral part of patient-centred medical care: A European consensus. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Jiang, W.; He, G. Effect of family enteral nutrition on nutritional status in elderly patients with esophageal carcinoma after minimally invasive radical surgery: A randomized trial. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 6760–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries-Ten Have, J.; Winkels, R.M.; Bloemhof, S.A.; Zondervan, A.; Krabbenborg, I.; Kampman, E.; Winkens, L.H. Determinants of healthy lifestyle behaviours in colorectal cancer survivors: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2025, 33, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Q.; Yin, Z.; Ding, L.; Ruan, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Gong, X.; Liu, W.; et al. Effect of preoperative oral nutritional supplements on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for gastrointestinal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2024, 103, e39844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurk, S.; Peeters, P.; Stellato, R.; Dorresteijn, B.; de Jong, P.; Jourdan, M.; Creemers, G.J.; Erdkamp, F.; de Jongh, F.; Kint, P.; et al. Skeletal muscle mass loss and dose-limiting toxicities in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés-Aguilar, R.; Malih, N.; Abbate, M.; Fresneda, S.; Yanez, A.; Bennasar-Veny, M. Validity of nutrition screening tools for risk of malnutrition among hospitalized adult patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1094–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouras, E.; Tsilidis, K.; Triggi, M.; Siargkas, A.; Chourdakis, M.; Haidich, A. Diet and risk of gastric cancer: An umbrella review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moazzen, S.; van der Sloot, K.W.J.; Bock, G.H.d.; Alizadeh, B.Z. Systematic review and meta-analysis of diet quality and colorectal cancer risk: Is the evidence of sufficient quality to develop recommendations? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veettil, S.K.; Wong, T.Y.; Loo, Y.S.; Playdon, M.C.; Lai, N.M.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Role of diet in colorectal cancer incidence: Umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective observational studies. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2037341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spei, M.-E.; Bellos, I.; Samoli, E.; Benetou, V. Post-diagnosis dietary patterns among cancer survivors in relation to all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sealy, M.J.; Nijholt, W.; Stuiver, M.M.; van der Berg, M.M.; Roodenburg, J.L.; van der Schans, C.P.; Ottery, F.D.; Jager-Wittenaar, H. Content validity across methods of malnutrition assessment in patients with cancer is limited. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 76, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilidis, K.K.; Markozannes, G.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Cariolou, M.; Balducci, K.; Vieira, R.; Kiss, S.; Aune, D.; Greenwood, D.C.; Dossus, L.; et al. Post-diagnosis adiposity, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, dietary factors, supplement use and colorectal cancer prognosis: Global Cancer Update Programme (CUP Global) summary of evidence grading. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 155, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.S.; Cariolou, M.; Markozannes, G.; Balducci, K.; Vieira, R.; Kiss, S.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Aune, D.; Greenwood, D.C.; González-Gil, E.M.; et al. Post-diagnosis dietary factors, supplement use and colorectal cancer prognosis: A Global Cancer Update Programme (CUP Global) systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 155, 445–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretwell, A.; Louca, P.; Cohoon, G.; Sakellaropoulou, A.; Caetano, M.D.P.H.; Koullapis, A.; Orange, S.T.; Malcomson, F.C.; Dobson, C.; Corfe, B.M. Still too little evidence: The role of diet in colorectal cancer survivorship—A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 3173–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aya, V.; Flórez, A.; Perez, L.; Ramírez, J.D. Association between physical activity and changes in intestinal microbiota composition: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewiasty, E.; Setiati, S.; Agustina, R.; Saldi, S.R.F.; Wisuda, N.Z.; Pramudita, A.; Kumaheri, M.; Fensynthia, G.; Rahmah, F.; Jonlean, R.; et al. Malnutrition Prevalence and Nutrient Intakes of Indonesian Older Adults in Institutionalized Care Setting: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 80, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Siahkamari, Z.; Rahmani, A.; Shohaimi, S.; Faghihi, S.H.; Mohammadi, M. Prevalence of severe malnutrition in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inciong, J.F.B.; Chaudhary, A.; Hsu, H.-S.; Joshi, R.; Seo, J.-M.; Trung, L.V.; Ungpinitpong, W.; Usman, N. Hospital malnutrition in northeast and southeast Asia: A systematic literature review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 39, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesari, P.R.; Jain, A.; Pulakurthi, Y.S.; Katamreddy, R.R.; Alvi, A.T.; Desai, R. Long-Term Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Prediabetes: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2024, 33, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.-L.; Shu, L.; Zheng, P.-F.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Si, C.-J.; Yu, X.-L.; Gao, W.; Zhang, L. Dietary patterns and colorectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 26, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Wang, X.-Q.; Wang, S.-F.; Wang, S.; Mu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Sheng, J.; Tao, F.-B. Dietary patterns and stomach cancer: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 1105–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, S.K.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Hursting, S.D. The world cancer research fund/American institute for cancer research third expert report on diet, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: Impact and future directions. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Galbete, C.; Hoffmann, G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Blarigan, E.L.; Fuchs, C.S.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Zhang, S.; Saltz, L.B.; Mayer, R.J.; Mowat, R.B.; Whittom, R.; Hantel, A.; Benson, A. Association of survival with adherence to the American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors after colon cancer diagnosis: The CALGB 89803/Alliance trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Knüppel, S.; Preterre, A.L.; Iqbal, K.; Bechthold, A.; De Henauw, S.; Michels, N.; Devleesschauwer, B.; et al. Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzzono, M.; Mannucci, A.; Grannò, S.; Zuppardo, R.A.; Galli, A.; Danese, S.; Cavestro, G.M. The role of diet and lifestyle in early-onset colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Cancers 2021, 13, 5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laviano, A.; Di Lazzaro, L.; Koverech, A. Nutrition support and clinical outcome in advanced cancer patients. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, R.; Sagawa, M.; Inaki, N.; Fukunaga, T.; Nunobe, S. Impact of perioperative immunonutrition on postoperative outcomes in patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2024, 16, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prausmüller, S.; Heitzinger, G.; Pavo, N.; Spinka, G.; Goliasch, G.; Arfsten, H.; Gabler, C.; Strunk, G.; Hengstenberg, C.; Hülsmann, M.; et al. Malnutrition outweighs the effect of the obesity paradox. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 1477–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellerba, F.; Serrano, D.; Johansson, H.; Pozzi, C.; Segata, N.; NabiNejad, A.; Piperni, E.; Gnagnarella, P.; Macis, D.; Aristarco, V.; et al. Colorectal cancer, Vitamin D and microbiota: A double-blind Phase II randomized trial (ColoViD) in colorectal cancer patients. Neoplasia 2022, 34, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Martínez, A.D.; Prior-Sánchez, I.; Fernández-Soto, M.L.; García-Olivares, M.; Novo-Rodríguez, C.; González-Pacheco, M.; Martínez-Ramirez, M.J.; Carmona-Llanos, A.; Jiménez-Sánchez, A.; Muñoz-Jiménez, C.; et al. Improving the nutritional evaluation in head neck cancer patients using bioelectrical impedance analysis: Not only the phase angle matters. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 2426–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, S.; Andersson, L.; Berglund, B. Early assessment of nutritional status in patients scheduled for colorectal cancer surgery. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2009, 32, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocarnik, J.M.; Compton, K.; Dean, F.E.; Fu, W.; Gaw, B.L.; Harvey, J.D.; Henrikson, H.J.; Lu, D.; Pennini, A.; Xu, R. Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 cancer groups from 2010 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 420–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, H.-N.; Huang, X.-Y.; Ge, Y.; An, G.-Y.; Yao, J.-N.; Zhang, H.-Y. Efectos preventivos de la dieta elemental para eventos adversos durante la quimioterapia en pacientes con cáncer de esófago: Una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis. Nutr. Hosp. 2024, 41, 666–676. [Google Scholar]

- Zaorsky, N.G.; Churilla, T.; Egleston, B.; Fisher, S.; Ridge, J.; Horwitz, E.; Meyer, J. Causes of death among cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, M.P.; Vanderbyl, B.L.; Kanbalian, M.; Windholz, T.Y.; Tran, A.-T.; Jagoe, R.T. A multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme for cancer cachexia improves quality of life. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2017, 7, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovic, B.; Jin, X.; Kennedy, S.A.; Hylands, M.; Pędziwiatr, M.; Kuriyama, A.; Gomaa, H.; Lee, Y.; Katsura, M.; Tada, M.; et al. Evaluating progression-free survival as a surrogate outcome for health-related quality of life in oncology: A systematic review and quantitative analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1586–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reckman, G.; Gomes-Neto, A.; Vonk, R.; Ottery, F.; van der Schans, C.; Navis, G.; Jager-Wittenaar, H. Anabolic competence: Assessment and integration of the multimodality interventional approach in disease-related malnutrition. Nutrition 2019, 65, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Elliott, S.; Baracos, V.; Chu, Q.; Prado, C. Key determinants of energy expenditure in cancer and implications for clinical practice. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, N.E.; Bauer, J.M.; Barazzoni, R.; Biolo, G.; Boirie, Y.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Krznariç, Z.; Nair, K.S.; et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: Recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotogni, P.; Ossola, M.; Passera, R.; Monge, T.; Fadda, M.; De Francesco, A.; Bozzetti, F. Home parenteral nutrition versus artificial hydration in malnourished patients with cancer in palliative care: A prospective, cohort survival study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 12, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milajerdi, A.; Namazi, N.; Larijani, B.; Azadbakht, L. The association of dietary quality indices and cancer mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochems, S.H.; Van Osch, F.H.; Bryan, R.T.; Wesselius, A.; van Schooten, F.J.; Cheng, K.K.; Zeegers, M.P. Impact of dietary patterns and the main food groups on mortality and recurrence in cancer survivors: A systematic review of current epidemiological literature. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e014530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffetta, P.; Couto, E.; Wichmann, J.; Ferrari, P.; Trichopoulos, D.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Van Duijnhoven, F.J.; Büchner, F.L.; Key, T.; Boeing, H.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and overall cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010, 102, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Lee, H.; Chung, H.; Park, J.C.; Shin, S.K.; Lee, S.K.; Hyung, W.J.; Lee, Y.C.; Noh, S.H. Impact of metabolic syndrome on oncologic outcome after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2014, 38, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, H.; Isenring, E.; Yates, P. The prevalence of nutrition impact symptoms and their relationship to quality of life and clinical outcomes in medical oncology patients. Support. Care Cancer 2009, 17, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubrak, C.; Olson, K.; Jha, N.; Jensen, L.; McCargar, L.; Seikaly, H.; Harris, J.; Scrimger, R.; Parliament, M.; Baracos, V.E. Nutrition impact symptoms: Key determinants of reduced dietary intake, weight loss, and reduced functional capacity of patients with head and neck cancer before treatment. Head Neck 2010, 32, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omlin, A.; Blum, D.; Wierecky, J.; Haile, S.R.; Ottery, F.D.; Strasser, F. Nutrition impact symptoms in advanced cancer patients: Frequency and specific interventions, a case–control study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2013, 4, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, K.; Morita, T.; Koshimoto, S.; Uno, T.; Katayama, H.; Tatara, R. Eating-related distress in advanced cancer patients with cachexia and family members: A survey in palliative and supportive care settings. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Kani, M.; Watanabe, D.; Miura, Y.; Chikaishi, W.; Tajima, J.Y.; Makiyama, A.; Yamada, Y.; Ohata, K.; Hirose, C.; et al. Cancer cachexia onset and survival outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer: Comparative assessment of the asian working group for cachexia and the European palliative care research collaborative criteria, and utility of modified glasgow prognostic score. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2025, 40, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, T.; Sari, I.N.; Wijaya, Y.T.; Julianto, N.M.; Muhammad, J.A.; Lee, H.; Chae, J.H.; Kwon, H.Y. Cancer cachexia: Molecular mechanisms and treatment strategies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.L.; Mirtallo, J.; Compher, C.; Dhaliwal, R.; Forbes, A.; Grijalba, R.F.; Hardy, G.; Kondrup, J.; Labadarios, D.; Nyulasi, I.; et al. Adult starvation and disease-related malnutrition: A proposal for etiology-based diagnosis in the clinical practice setting from the International Consensus Guideline Committee. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2010, 34, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T.; Jensen, G.; Correia, M.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Fukushima, R.; Higashiguchi, T.; Baptista, G.; Barazzoni, R.; Blaauw, R.; Coats, A.; et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition—A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019, 10, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Stobäus, N.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Schulzke, J.-D.; Pirlich, M. Hand grip strength: Outcome predictor and marker of nutritional status. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 30, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Caragescu, C.M.; Vicaș, L.G.; Antonescu, A.M.; Marian, N.A.; Gligor, O.; Mureșan, M.E.; Grigore, P.-A.; Marian, E. Effects of Dietary Interventions on Nutritional Status in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010240

Caragescu CM, Vicaș LG, Antonescu AM, Marian NA, Gligor O, Mureșan ME, Grigore P-A, Marian E. Effects of Dietary Interventions on Nutritional Status in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010240

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaragescu (Lup), Camelia Maria, Laura Grațiela Vicaș, Angela Mirela Antonescu, Nicole Alina Marian, Octavia Gligor, Mariana Eugenia Mureșan, Patricia-Andrada Grigore, and Eleonora Marian. 2026. "Effects of Dietary Interventions on Nutritional Status in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Systematic Review" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010240

APA StyleCaragescu, C. M., Vicaș, L. G., Antonescu, A. M., Marian, N. A., Gligor, O., Mureșan, M. E., Grigore, P.-A., & Marian, E. (2026). Effects of Dietary Interventions on Nutritional Status in Patients with Gastrointestinal Cancers: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines, 14(1), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010240