Predictive Value of Platelet-Based Indexes for Mortality in Sepsis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics

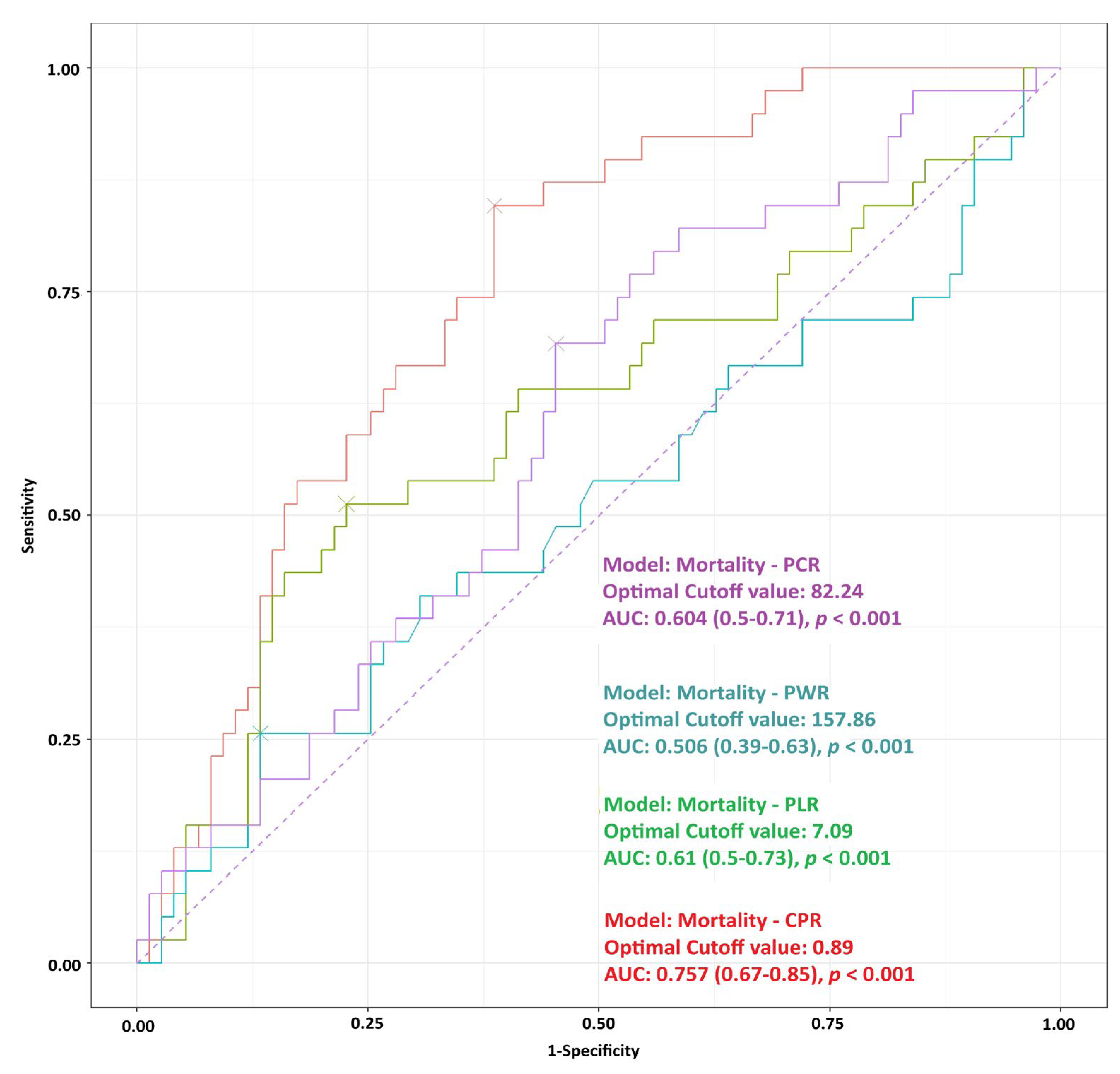

3.2. ROC Analysis for Mortality

3.3. Multivariate Logistic Regression for Mortality

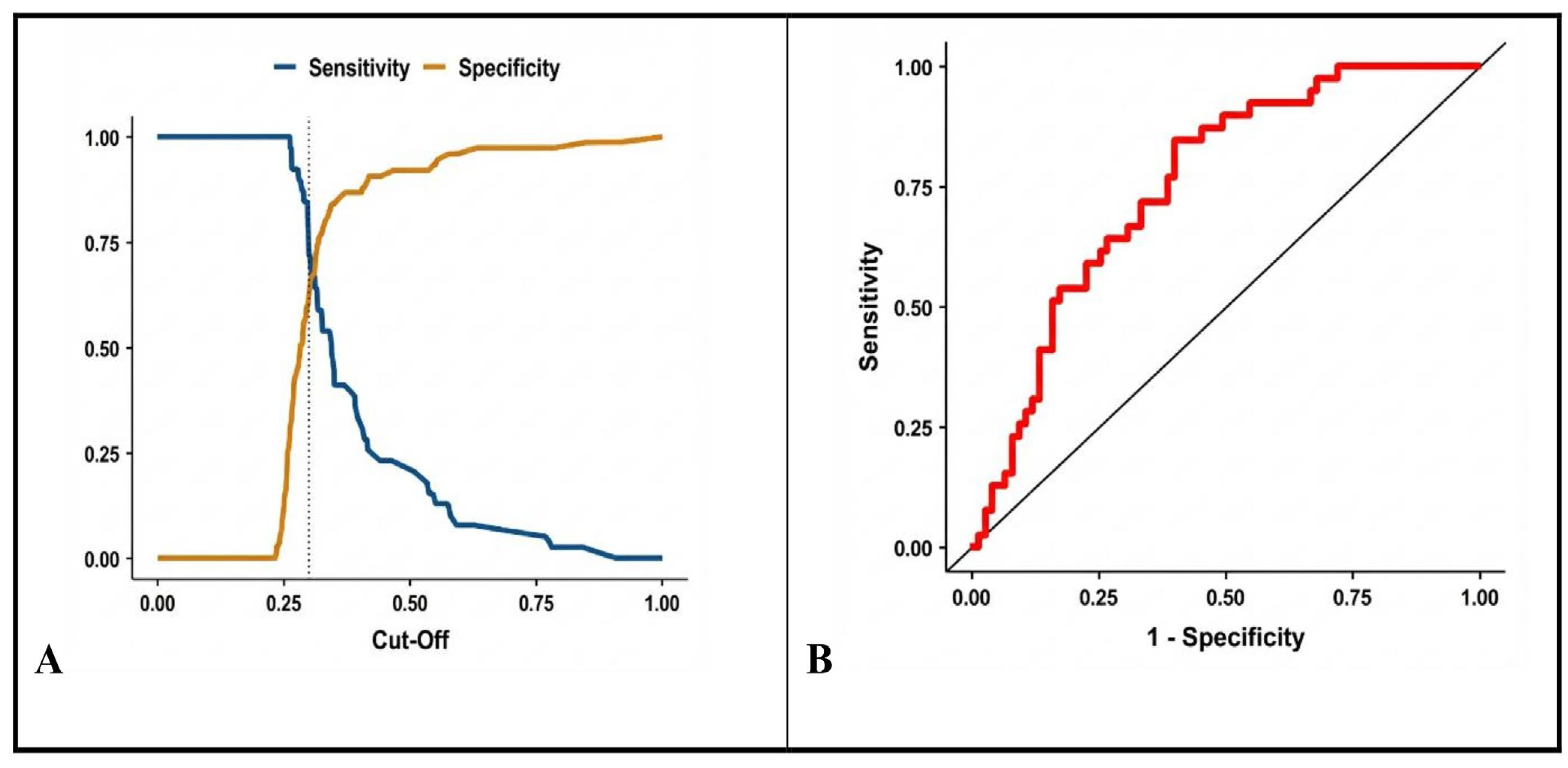

3.4. ROC Curve for the Final Model

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CPR | C-reactive protein-to-platelet ratio |

| PLR | Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PWR | Platelet-to-white blood cell ratio |

| PCR | Platelet-to-creatinine ratio |

| WBC | White blood cell count |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| qSOFA | Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| RDW | Red cell distribution width |

| MPV | Mean platelet volume |

| DIC | Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| AUC | Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D.R.; Colombara, D.V.; Ikuta, K.S.; Kissoon, N.; Finfer, S.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Sepsis Incidence and Mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, C.W.; Liu, V.X.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Rea, T.D.; Scherag, A.; Rubenfeld, G.; Kahn, J.M.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Singer, M.; et al. Assessment of Clinical Criteria for Sepsis for the Third International Consensus Definitions (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Fu, Z.; Huang, W.; Huang, K. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Sepsis: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibot, S.; Béné, M.C.; Noel, R.; Massin, F.; Guy, J.; Cravoisy, A.; Barraud, D.; Bittencourt, M.D.C.; Quenot, J.-P.; Bollaert, P.-E.; et al. Combination Biomarkers to Diagnose Sepsis in the Critically Ill Patient. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoto, S.; Lupoi, D.M.; Valeriani, E.; Fogolari, M.; Locorriere, L.; Beretta Anguissola, G.; Battifoglia, G.; Caputo, D.; Coppola, A.; Costantino, S.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy and Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Septic Patients outside the Intensive Care Unit. Medicina 2021, 57, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salciccioli, J.D.; Marshall, D.C.; Pimentel, M.A.; Santos, M.D.; Pollard, T.; Celi, L.A.; Shalhoub, J. The Association between the Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio and Mortality in Critical Illness: An Observational Cohort Study. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Cao, T.; Ji, T.; Luo, Y.; Huang, J.; Ma, K. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Is Associated with Outcomes in Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1336456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Lei, J.; Xiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Feng, J.; Xu, W.; Ou, J.; Yang, B.; Zhang, L. Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio: A Potential Novel Predictor for Acute Kidney Injury in the Intensive Care Unit. Ren. Fail. 2022, 44, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, S.M.A.; Lobo, F.R.M.; Bota, D.P.; Lopes-Ferreira, F.; Soliman, H.M.; Mélot, C.; Vincent, J.-L. C-Reactive Protein Levels Correlate with Mortality and Organ Failure in Critically Ill Patients. Chest 2003, 123, 2043–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzani, O.T.; Zampieri, F.G.; Forte, D.N.; Azevedo, L.C.P.; Park, M. C-Reactive Protein/Albumin Ratio Predicts 90-Day Mortality of Septic Patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogagnolo, A.; Taccone, F.S.; Campo, G.; Montanari, G.; Capatti, B.; Ferraro, G.; Erriquez, A.; Ragazzi, R.; Creteur, J.; Volta, C.A.; et al. Impaired Platelet Reactivity in Patients with Septic Shock: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Platelets 2020, 31, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Song, J.; Ma, H.; Hua, N.; Bai, Y.; Ju, Y.; Shen, J.-W.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, S. The Crucial Roles of Platelets as Immune Mediators in Sepsis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 12825–12845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitchford, S.C.; Pan, D. Platelet Purinergic Receptors and Non-Thrombotic Diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 181, 513–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Hilger, A.; Zarbock, A.; Rossaint, J. Platelets at the Crossroads of Pro-Inflammatory and Resolution Pathways during Inflammation. Cells 2022, 11, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. Youden’s Index and the Weight of Evidence. Methods Inf. Med. 2015, 54, 198–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorup, C.V.; Christensen, S.; Hvas, A.M. Immature Platelets as a Predictor of Disease Severity and Mortality in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 46, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.; Cho, Y.S.; Sohn, Y.J.; Hyun, J.H.; Ahn, S.M.; Lee, W.J.; Seong, H.; Ahn, J.Y.; Jeong, S.J.; et al. A Modified Simple Scoring System Using the Red Blood Cell Distribution Width, Delta Neutrophil Index, and Mean Platelet Volume-to-Platelet Count to Predict 28-Day Mortality in Patients with Sepsis. J. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 36, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Khalid, S.; Jiang, L. Diagnostic and Predictive Performance of Biomarkers in Patients with Sepsis in an Intensive Care Unit. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Gao, J.; Huang, K.; Xu, D.; Ru, H. Association between Platelet Levels and 28-Day Mortality in Patients with Sepsis: A Retrospective Analysis of a Large Clinical Database (MIMIC-IV). Front. Med. 2022, 9, 833996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schupp, T.; Weidner, K.; Rusnak, J.; Jawhar, S.; Forner, J.; Dulatahu, F.; Brück, L.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Kittel, M.; Bertsch, T.; et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Role of Platelets in Sepsis and Septic Shock. Platelets 2023, 34, 2131753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderschueren, S.; De Weerdt, A.; Malbrain, M.; Vankersschaever, D.; Frans, E.; Wilmer, A.; Bobbaers, H. Thrombocytopenia and Prognosis in Intensive Care. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 28, 1871–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assinger, A.; Schrottmaier, W.C.; Salzmann, M.; Rayes, J. Platelets in Sepsis: An Update on Experimental Models and Clinical Data. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydemir, H.; Piskin, N.; Akduman, D.; Kokturk, F.; Aktas, E. Platelet and Mean Platelet Volume Kinetics in Adult Patients with Sepsis. Platelets 2015, 26, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbi, G.A.; Chaari, A. Platelet Parameters in Septic Shock: Clinical Usefulness and Prognostic Value. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2020, 31, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orak, M.; Karakoç, Y.; Ustundag, M.; Yildirim, Y.; Celen, M.K.; Güloglu, C. An Investigation of the Effects of the Mean Platelet Volume, Platelet Distribution Width, Platelet/Lymphocyte Ratio, and Platelet Counts on Mortality in Patients with Sepsis Who Applied to the Emergency Department. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 21, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez Hernández, R.; Ramasco Rueda, F. Biomarkers as Prognostic Predictors and Therapeutic Guide in Critically Ill Patients: Clinical Evidence. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lee, J.; Jung, Y.S.; Kwon, W.Y.; Oh, D.K.; Park, M.H.; Lim, C.-M.; Lee, S.-M. Preexisting Clinical Frailty Is Associated with Worse Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 50, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koozi, H.; Lengquist, M.; Frigyesi, A. C-Reactive Protein as a Prognostic Factor in Intensive Care Admissions for Sepsis: A Swedish Multicenter Study. J. Crit. Care 2020, 56, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xie, Y.; Feng, T.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, W.; Tian, R.; Wang, R. Prognostic Value of Short-Term Dynamic Changes in Platelet Count in Adult Patients with Sepsis Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2020, 32, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Z.; Ouyang, L. Association between Neutrophil–Platelet Ratio and 28-Day Mortality in Patients with Sepsis: A Retrospective Analysis Based on the MIMIC-IV Database. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; She, P. Research Advances in the Diagnosis of Neonatal Sepsis. J. Biosci. Med. 2025, 13, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, T.; Fu, H.; Lin, F.; Li, C.; Bai, Q.; Jin, Z. C-Reactive Protein-to-Platelet Ratio as an Early Biomarker for Differentiating Neonatal Late-Onset Sepsis in Neonates with Pneumonia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Dong, G.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Fang, P.; Qi, M. Predictive Value of C-Reactive Protein-to-Albumin Ratio for Neonatal Sepsis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 3207–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Yu, S.; Qin, J.; Peng, M.; Qian, J.; Zhou, P. Prognostic Value of Platelet Count-Related Ratios on Admission in Patients with Pyogenic Liver Abscess. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, L.; Cheng, M.; Xie, W. Predictive Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet Ratio in In-Hospital Mortality in Septic Patients. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Han, D.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Lyu, J.; Yin, H. Risk Factor Analysis and Nomogram for Predicting In-Hospital Mortality in ICU Patients with Sepsis and Lung Infection. BMC Pulm. Med. 2022, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Shu, Y.; Liu, Y. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Marker for In-Hospital Mortality of Patients with Sepsis: A Secondary Analysis Based on a Single-Center, Retrospective Cohort Study. Medicine 2019, 98, e18029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, W. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Predictor of Mortality for Sepsis: Interaction Effect with Disease Severity—A Retrospective Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e022896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, H.; Lu, L.; Guo, R. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio, and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Associated with 28-Day All-Cause Mortality in Septic Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: A Retrospective Analysis of the MIMIC-IV Database. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foy, B.H.; Carlson, J.C.T.; Aguirre, A.D.; Higgins, J.M. Platelet–White Cell Ratio Is More Strongly Associated with Mortality than Other Common Risk Ratios Derived from Complete Blood Counts. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez-Páez, J.L.; Legua, P.; Vélez-Páez, P.; Irigoyen, E.; Andrade, H.; Jara, A.; López, F.; Pérez-Galarza, J.; Baldeón, L. Mean Platelet Volume and MPV/Platelet Ratio as Predictors of Severity and Mortality in Sepsis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iba, T.; Watanabe, E.; Umemura, Y.; Wada, T.; Hayashida, K.; Kushimoto, S.; Japanese Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guideline Working Group for Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation; Wada, H. Sepsis-Associated Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Its Differential Diagnoses. J. Intensive Care 2019, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, J. Development and Validation of a Prediction Model for In-Hospital Mortality of Patients with Severe Thrombocytopenia. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, M.; Cao, S.; Hua, L.; Zhang, K. Prediction of 28-Day Mortality in Patients with Sepsis Based on a Predictive Model: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2025, 53, 03000605251361104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou Chebl, R.; Jamali, S.; Sabra, M.; Safa, R.; Berbari, I.; Shami, A.; Makki, M.; Tamim, H.; Abou Dagher, G. Lactate/Albumin Ratio as a Predictor of In-Hospital Mortality in Septic Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 550182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardon-Bounes, F.; Ruiz, S.; Gratacap, M.-P.; Garcia, C.; Payrastre, B.; Minville, V. Platelets Are Critical Key Players in Sepsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Yang, F.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Q.; Shi, H.; Huang, S.; Zhao, X.; Xiu, L.; et al. Platelets as a Prognostic Marker for Sepsis: A Cohort Study from the MIMIC-III Database. Medicine 2020, 99, e23151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total (n = 114) | Mortality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivors (n = 75) | Non-Survivors (n = 39) | p-Value | ||

| Age, years | 71.25 ± 8.4 71 (65.8–77) | 71.11 ± 8.2 72 (65–76) | 71.5 ± 9 71 (67–79) | 0.647 |

| Sex, male | 69 (60.5%) | 49 (65.3%) | 20 (51.3%) | 0.096 |

| Shock status | ||||

| Septic shock | 38 (33.3%) | 17 (22.7%) | 21 (53.8%) | 0.001 |

| Sepsis | 76 (66.7%) | 58 (77.3%) | 18 (46.2%) | |

| Biochemical parameters | ||||

| CRP (mg/L) | 122.9 ± 22.2 128.9 (106.1–137.8) | 114.04 ± 21.4 120.5 (94.1–130.5) | 140 ± 10.9 138.5 (131.5–148.7) | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocytes (106 cells/L) | 1.5 ± 0.5 1.4 (1.2–1.8) | 1.57 ± 0.53 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | 1.23 ± 0.5 1.2 (1–1.6) | 0.001 |

| WBC (106 cells/L) | 15.4 ± 4.7 16.3 (13.4–18.5) | 15.44 ± 4.34 16.3 (13.4–18.2) | 15.4 ± 5.31 16.4 (13.1–19) | 0.558 |

| PLT (109 cells/L) | 136.4 ± 54.7 140 (100–169) | 146.6 ± 53.1 146 (118–189) | 116.9 ± 53.04 118 (73–158) | 0.009 |

| Neutrophils (106 cells/L) | 12.2 ± 4.1 13.9 (11.3–16.1) | 13.2 ± 3.84 13.8 (11.3–16) | 13.3 ± 4.7 14.2 (10.5–17.1) | 0.525 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 168.0 ± 123.8 114.9 (85.7–207.7) | 168.0 ± 123.8 106.1 (84.9–247.5) | 168.0 ± 114.9 159.1 (85.7–185.6) | 0.774 |

| Derived platelet-based indices (calculated ratios) | ||||

| CPR | 1.22 ± 0.99 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.03 ± 0.92 0.76 (0.6–1.1) | 1.59 ± 1.03 1.24 (0.9–1.77) | <0.0001 |

| PLR | 123.2 ± 119.8 93.3 (62.5–138.8) | 120.4 ± 117.7 91 (66.7–138.3) | 128.7 ± 125.3 96.9 (54.3–157.9) | 0.912 |

| PWR | 11.1 ± 10.1 9.2 (6–12.2) | 11.77 ± 10.9 9.5 (7.4–12.6) | 9.7 ± 8.3 7.1 (4.8–11.8) | 0.047 |

| PCR | 100 ± 68.1 76.6 (51.8–137.1) | 109.1 ± 71.4 93 (55.3–147.5) | 82.7 ± 58.3 68.4 (45.1–104.9) | 0.068 |

| Model | Variable | Multivariate | AIC | R2McF | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | p-Value | |||||

| Model A | CPR PWR PLR PCR | 0.915 (0.70–2.14) 0.570 (0.42–0.78) 1.044 (1.02–1.07) 0.997 (0.99–1.01) | 0.47 <0.001 <0.001 0.503 | 125 | 0.214 | 0.826 |

| Model B | CPR PWR | 1.798 (1.11–2.92) 0.999 (0.96–1.04) | 0.018 0.962 | 144 | 0.055 | 0.754 |

| Model C | CPR PLR | 1.977 (1.22–3.21) 1.002 (0.99–1.01) | 0.006 0.199 | 143 | 0.066 | 0.772 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Drăgoescu, A.N.; Turcu-Stiolica, A.; Zorilă, M.V.; Ungureanu, B.S.; Drăgoescu, P.O.; Stănculescu, A.D. Predictive Value of Platelet-Based Indexes for Mortality in Sepsis. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010211

Drăgoescu AN, Turcu-Stiolica A, Zorilă MV, Ungureanu BS, Drăgoescu PO, Stănculescu AD. Predictive Value of Platelet-Based Indexes for Mortality in Sepsis. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010211

Chicago/Turabian StyleDrăgoescu, Alice Nicoleta, Adina Turcu-Stiolica, Marian Valentin Zorilă, Bogdan Silviu Ungureanu, Petru Octavian Drăgoescu, and Andreea Doriana Stănculescu. 2026. "Predictive Value of Platelet-Based Indexes for Mortality in Sepsis" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010211

APA StyleDrăgoescu, A. N., Turcu-Stiolica, A., Zorilă, M. V., Ungureanu, B. S., Drăgoescu, P. O., & Stănculescu, A. D. (2026). Predictive Value of Platelet-Based Indexes for Mortality in Sepsis. Biomedicines, 14(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010211