Targeting AKT via SC79 for Photoreceptor Preservation in Retinitis Pigmentosa Mouse Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. 661W Cell Culture and MTT Assay

2.2. Animals

2.3. Intravitreal Injections

2.4. Electroretinograms (ERGs)

2.5. Optomotor Response

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

2.7. Fluorescence Intensity Quantification

2.8. Retinal Thickness Quantification

2.9. Cone Photoreceptor Quantifications

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

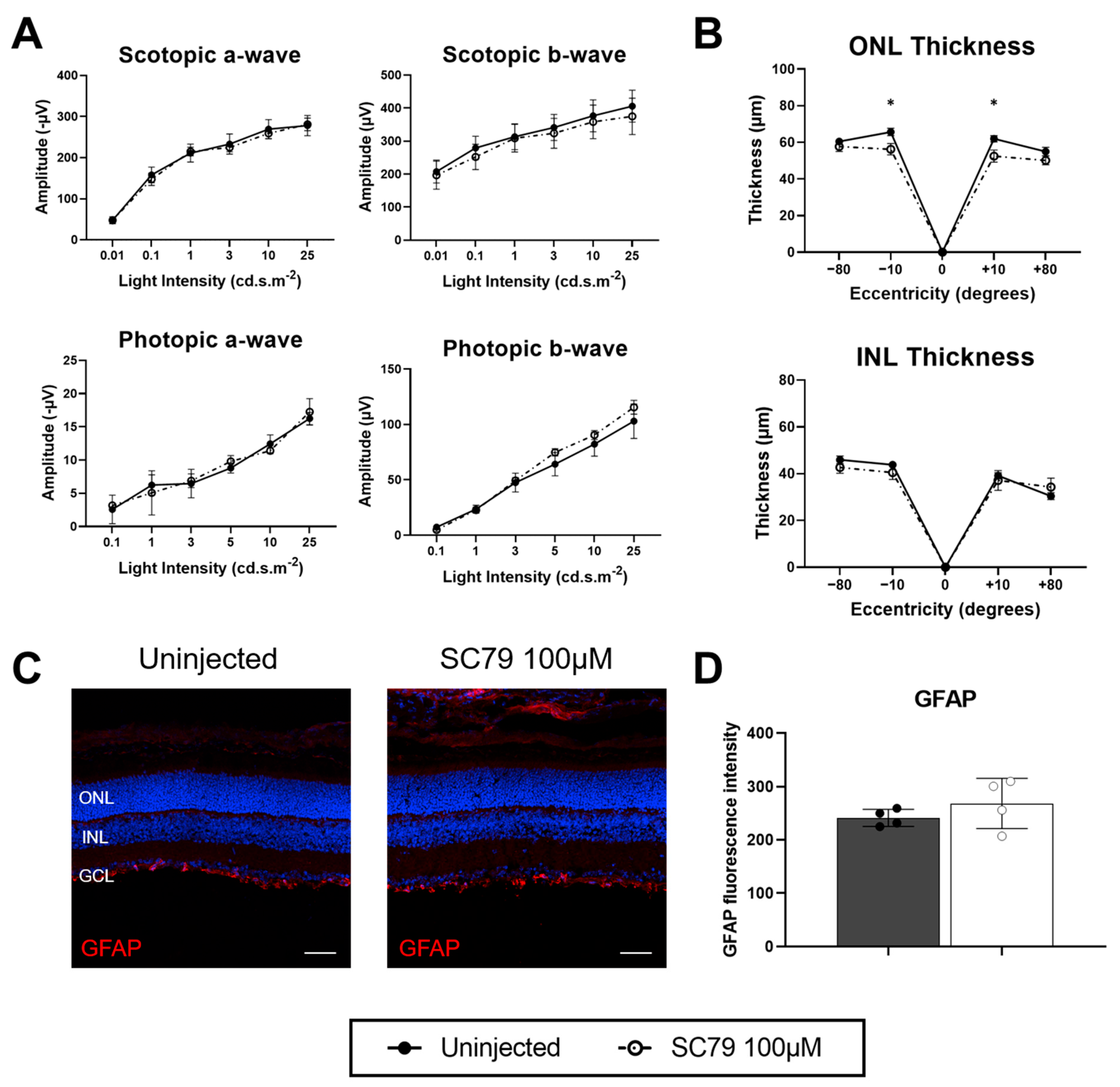

3.1. SC79 Treatment in Healthy Conditions

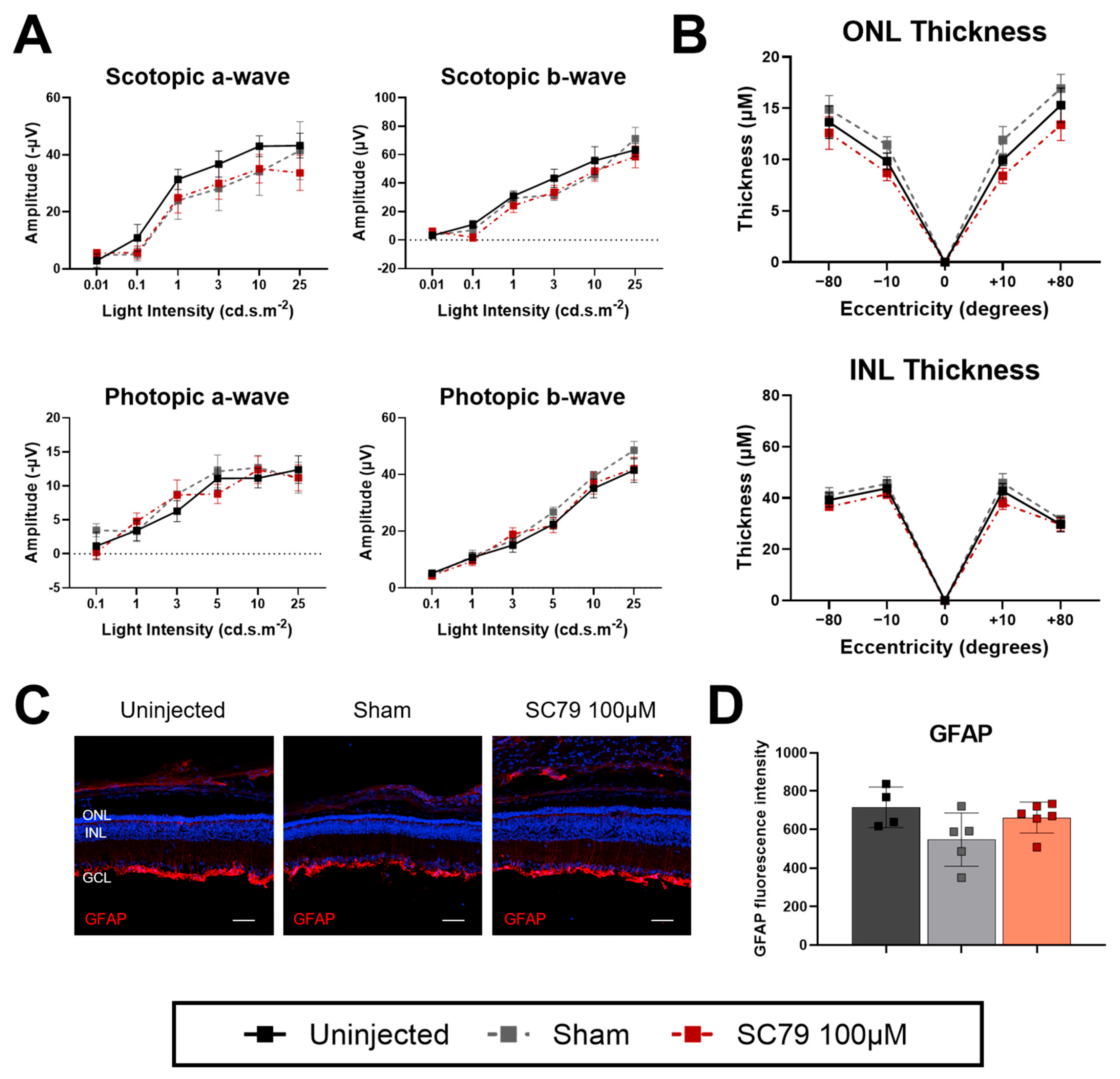

3.2. SC79 Treatment in Retinitis Pigmentosa Mice

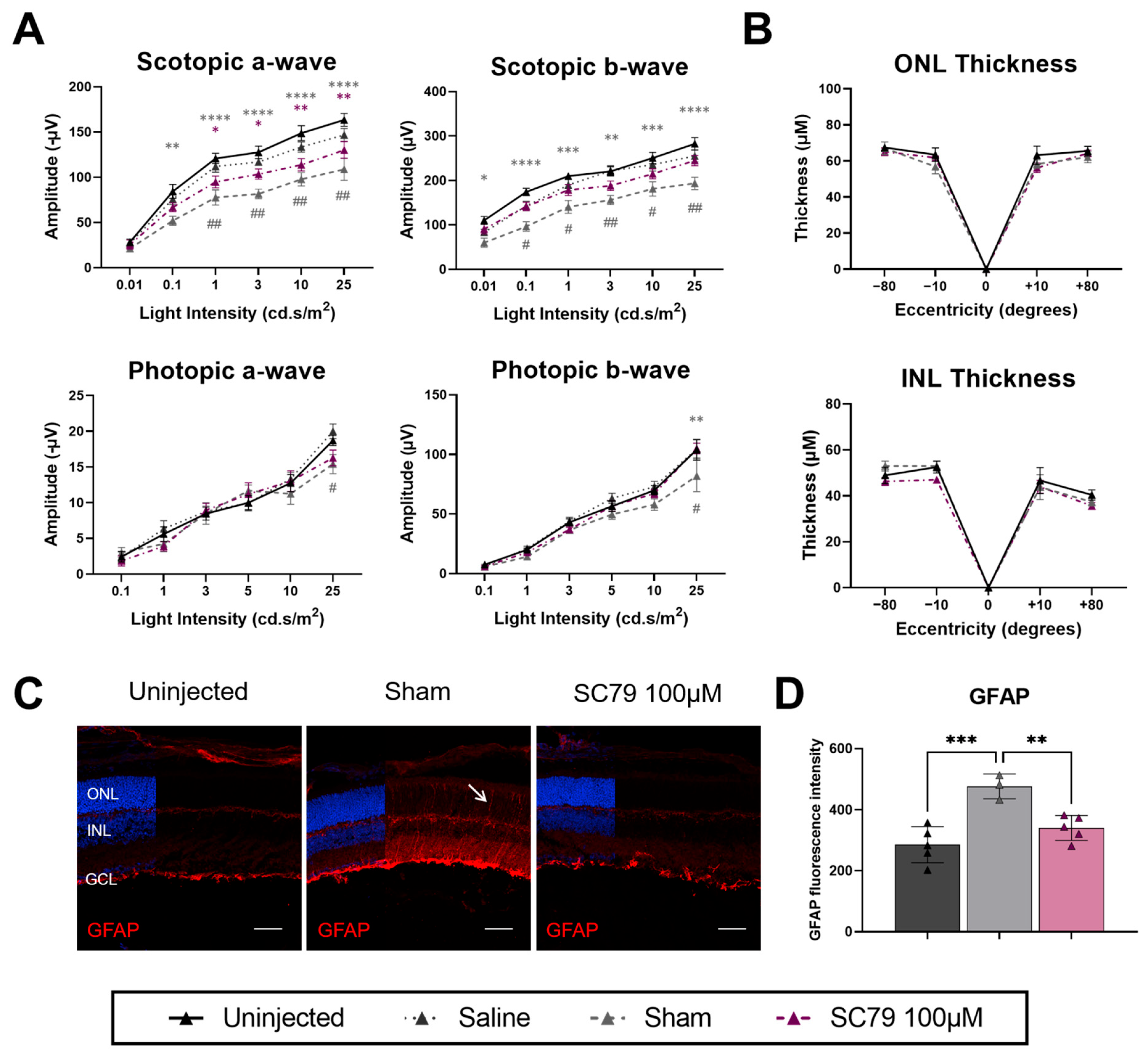

3.3. Effects of Increased SC79 Dose in Healthy Mice

3.4. Minimal Benefits of Increased SC79 Dose in Retinitis Pigmentosa Mice

4. Discussion

4.1. Retinal Changes After Intravitreal Sham Injections

4.2. Model-Specific Benefits of SC79 on Rod Photoreceptors

4.3. Cone Photoreceptor Morphology Preservation

4.4. Translational Considerations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IRD | Inherited retinal disease |

| rd1 | Retinal degeneration 1 |

| PKB | Protein kinase B |

| rd10 | Retinal degeneration 10 |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| ERG | Electroretinogram |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| NGS | Normal goat serum |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| SP | Superior peripheral |

| SC | Superior central |

| IC | Inferior central |

| IP | Inferior peripheral |

| ONL | Outer nuclear layer |

| INL | Inner nuclear layer |

| GCL | Ganglion cell layer |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

References

- Cross, N.; van Steen, C.; Zegaoui, Y.; Satherley, A.; Angelillo, L. Retinitis pigmentosa: Burden of disease and current unmet needs. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 16, 1993–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of Texas Health Science Center. Retinal Information Network; The University of Texas Health Science Center: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brunet, A.A.; Harvey, A.R.; Carvalho, L.S. Primary and secondary cone cell death mechanisms in inherited retinal diseases and potential treatment options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.R.; Brunet, A.; Greenberg, M.E. Cellular survival: A play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 2905–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomary, C.; Cullen, J.; Jones, S.E. Inactivation of the Akt survival pathway during photoreceptor apoptosis in the retinal degeneration mouse. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; He, J.; Johnson, D.K.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lutty, G.A.; Duh, E.J.; Carmeliet, P.; Semba, R.D. Deletion of placental growth factor prevents diabetic retinopathy and is associated with Akt activation and HIF1α-VEGF pathway inhibition. Diabetes 2015, 64, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, T.; Shimura, M.; Tomita, H.; Akiyama, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kudou, H.; Tamai, M. Intrinsic activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and its neuroprotective effect against retinal injury. Curr. Eye Res. 2003, 26, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.-W.; Yang, Y. SC79 protects dopaminergic neurons from oxidative stress. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 12639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.-Q.; Huang, W.; Li, K.-R.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Cao, G.-F.; Cao, C.; Jiang, Q. SC79 protects retinal pigment epithelium cells from UV radiation via activating Akt-Nrf2 signaling. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 60123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougald, D.S.; Papp, T.E.; Zezulin, A.U.; Zhou, S.; Bennett, J. AKT3 gene transfer promotes anabolic reprogramming and photoreceptor neuroprotection in a pre-clinical model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1313–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drag, S.; Dotiwala, F.; Upadhyay, A.K. Gene therapy for retinal degenerative diseases: Progress, challenges, and future directions. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administation. LUXTURNA. 2017. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/luxturna (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Darrow, J.J. Luxturna: FDA documents reveal the value of a costly gene therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, S.; Scherf, B.G.; Del Punta, K.; Didkovsky, N.; Heintz, N.; Roska, B. Genetic address book for retinal cell types. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakami, S.; Maeda, T.; Bereta, G.; Okano, K.; Golczak, M.; Sumaroka, A.; Roman, A.J.; Cideciyan, A.V.; Jacobson, S.G.; Palczewski, K. Probing mechanisms of photoreceptor degeneration in a new mouse model of the common form of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa due to P23H opsin mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 10551–10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunet, A.A.; Fuller-Carter, P.I.; Miller, A.L.; Voigt, V.; Vasiliou, S.; Rashwan, R.; Hunt, D.M.; Carvalho, L.S. Validating fluorescent Chrnb4.EGFP mouse models for the study of cone photoreceptor degeneration. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno-Hernández, R.; Cantó, A.; Fernández-Carbonell, A.; Olivar, T.; Hernández-Rabaza, V.; Almansa, I.; Miranda, M. Thioredoxin delays photoreceptor degeneration, oxidative and inflammation alterations in retinitis pigmentosa. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 590572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, B.D.; Toker, A. AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating the network. Cell 2017, 169, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakami, S.; Kolesnikov, A.V.; Kefalov, V.J.; Palczewski, K. P23H opsin knock-in mice reveal a novel step in retinal rod disc morphogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 1723–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwick, S.R.; Xiao, H.; Wolff, D.; Wang, J.; Perry, E.; Marshall, B.; Smith, S.B. Sigma 1 receptor activation improves retinal structure and function in the RhoP23H/+ mouse model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Exp. Eye Res. 2023, 230, 109462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, H.; Pham, N.C.; Boyd, T.; Santoso, J.; Palczewski, K.; Vinberg, F. Homeostatic plasticity in the retina is associated with maintenance of night vision during retinal degenerative disease. eLife 2020, 9, e59422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvao, J.; Davis, B.; Tilley, M.; Normando, E.; Duchen, M.R.; Cordeiro, M.F. Unexpected low-dose toxicity of the universal solvent DMSO. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombrebueno, J.R.; Luo, C.; Guo, L.; Chen, M.; Xu, H. Intravitreal injection of normal saline induces retinal degeneration in the C57BL/6J mouse. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espitia-Arias, M.D.; de la Villa, P.; Paleo-García, V.; Germain, F.; Milla-Navarro, S. Oxidative Model of Retinal Neurodegeneration Induced by Sodium Iodate: Morphofunctional Assessment of the Visual Pathway. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter-Dawson, L.; LaVail, M.; Sidman, R. Differential effect of the rd mutation on rods and cones in the mouse retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1978, 17, 489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, T.; Lyubarsky, A.; Bennett, J. Dark-rearing the rd10 mouse: Implications for therapy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 723, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsyr, O.; Sánchez-Sáez, X.; Martínez-Gil, N.; de Juan, E.; Lax, P.; Maneu, V.; Cuenca, N. Gradual Increase in Environmental Light Intensity Induces Oxidative Stress and Inflammation and Accelerates Retinal Neurodegeneration. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisciak, D.T.; Darrow, R.M.; Barsalou, L.; Kutty, R.K.; Wiggert, B. Susceptibility to retinal light damage in transgenic rats with rhodopsin mutations. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.E.; van Veen, T.; Ekström, P.A. Differential Akt activation in the photoreceptors of normal and rd1 mice. Cell Tissue Res. 2005, 320, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianesini, C.; Hiragaki, S.; Laurent, V.; Hicks, D.; Tosini, G. Cone viability is affected by disruption of melatonin receptors signaling. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Xiong, G.; Yang, W. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 promotes the survival of photoreceptors in retinitis pigmentosa. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, R.R.; Kompella, U.B. Intravitreal, subretinal, and suprachoroidal injections: Evolution of microneedles for drug delivery. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 34, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.-T.; Liu, W.; Xue, C.-R.; Wu, S.-X.; Chen, W.-N.; Lin, X.-J.; Lin, X. AKT activator SC79 protects hepatocytes from TNF-α-mediated apoptosis and alleviates d-Gal/LPS-induced liver injury. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 316, G387–G396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jing, Z.-T.; Wu, S.-X.; He, Y.; Lin, Y.-T.; Chen, W.-N.; Lin, X.-J.; Lin, X. A novel AKT activator, SC79, prevents acute hepatic failure induced by Fas-mediated apoptosis of hepatocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyzogubov, V.V.; Bora, N.S.; Tytarenko, R.G.; Bora, P.S. Polyethylene glycol induced mouse model of retinal degeneration. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 127, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, M.; Chen, F.; Goldberg, J.L.; Sabel, B.A. Nanomedicine and drug delivery to the retina: Current status and implications for gene therapy. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2022, 395, 1477–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.; Lim, P.; Wagle, S.R.; Ionescu, C.M.; Kovacevic, B.; McLenachan, S.; Carvalho, L.; Brunet, A.; Mooranian, A.; Al-Salami, H. Nanoparticle-Based gene therapy strategies in retinal delivery. J. Drug Target. 2025, 33, 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brunet, A.A.; Gilbert, K.; Miller, A.L.; James, R.E.; Lim, X.R.; Harvey, A.R.; Carvalho, L.S. Targeting AKT via SC79 for Photoreceptor Preservation in Retinitis Pigmentosa Mouse Models. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010195

Brunet AA, Gilbert K, Miller AL, James RE, Lim XR, Harvey AR, Carvalho LS. Targeting AKT via SC79 for Photoreceptor Preservation in Retinitis Pigmentosa Mouse Models. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010195

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrunet, Alicia A., Kate Gilbert, Annie L. Miller, Rebekah E. James, Xin Ru Lim, Alan R. Harvey, and Livia S. Carvalho. 2026. "Targeting AKT via SC79 for Photoreceptor Preservation in Retinitis Pigmentosa Mouse Models" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010195

APA StyleBrunet, A. A., Gilbert, K., Miller, A. L., James, R. E., Lim, X. R., Harvey, A. R., & Carvalho, L. S. (2026). Targeting AKT via SC79 for Photoreceptor Preservation in Retinitis Pigmentosa Mouse Models. Biomedicines, 14(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010195