Association of Bach1 Gene Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

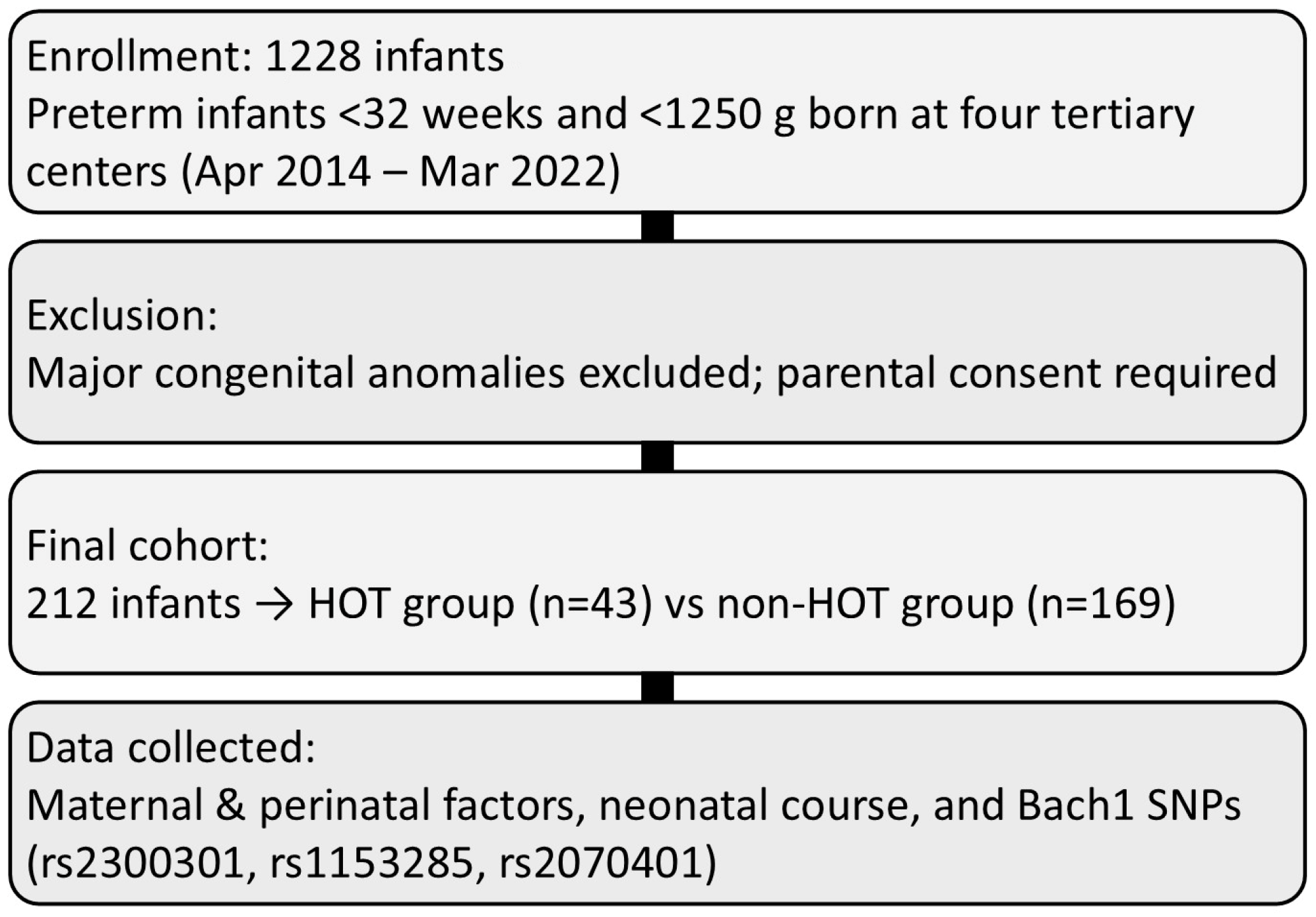

2.1. Study Design and Patient Groups

2.2. Patient Clinical Data

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lignelli, E.; Palumbo, F.; Myti, D.; Morty, R.E. Recent advances in our understanding of the mechanisms of lung alveolarization and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2019, 317, L832–L887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, E.A.; Dysart, K.; Gantz, M.G.; McDonald, S.; Bamat, N.A.; Keszler, M.; Kirpalani, H.; Laughon, M.M.; Poindexter, B.B.; Duncan, A.F.; et al. The Diagnosis of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Very Preterm Infants. An Evidence-based Approach. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, T.; Inoue, H.; Sakemi, Y.; Ochiai, M.; Yamashita, H.; Ohga, S.; Neonatal Research Network of Japan. Trends in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Among Extremely Preterm Infants in Japan, 2003–2016. J. Pediatr. 2021, 230, 119–125.E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, R.; Hasebe, M.; Nakamura, T.; Namba, F. Variability in Home Oxygen Therapy Practices for Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Japan: A Questionnaire Survey. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 2025, 61, 1495–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.P.; Lee, E.P.; Chiang, M.C. The Characteristics and Two-Year Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Home Oxygen Therapy among Preterm Infants with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: A Retrospective Study in a Medical Center in Taiwan. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekharan, P.; Lakshminrusimha, S.; Chowdhury, D.; Van Meurs, K.; Keszler, M.; Kirpalani, H.; Das, A.; Walsh, M.C.; McGowan, E.C.; Higgins, R.D.; et al. Early Hypoxic Respiratory Failure in Extreme Prematurity: Mortality and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20193318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Smith, L.; Hofheimer, J.A.; McGowan, E.C.; O’Shea, T.M.; Pastyrnak, S.; Carter, B.S.; Helderman, J.; Check, J.; Neal, C.; et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia and neurobehavioural outcomes at birth and 2 years in infants born before 30 weeks. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2023, 108, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumbaugh, J.E.; Bell, E.F.; Grey, S.F.; DeMauro, S.B.; Vohr, B.R.; Harmon, H.M.; Bann, C.M.; Rysavy, M.A.; Logan, J.W.; Colaizy, T.T.; et al. Behavior Profiles at 2 Years for Children Born Extremely Preterm with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J. Pediatr. 2020, 219, 152–159.E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Wu, T.J.; Jing, X.; Day, B.W.; Pritchard, K.A.; Naylor, S.; Teng, R.J. Temporal Dynamics of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavò, L.; Perrone, S.; Viola, V.; Marseglia, L.; Di Rosa, G.; Gitto, E. Oxidative Stress and Respiratory Diseases in Preterm Newborns. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, L.; Vento, G.; Loddo, C.; Tirone, C.; Iavarone, F.; Raimondi, F.; Dani, C.; Fanos, V. Oxidative Stress and Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Evidences From Microbiomics, Metabolomics, and Proteomics. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.Y.; Kim, H.S. Oxidative stress and the antioxidant enzyme system in the developing brain. Korean J. Pediatr. 2013, 56, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laforgia, N.; Di Mauro, A.; Favia Guarnieri, G.; Varvara, D.; De Cosmo, L.; Panza, R.; Capozza, M.; Baldassarre, M.E.; Resta, N. The Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathomechanism of Congenital Malformations. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 7404082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusto, K.; Wanczyk, H.; Jensen, T.; Finck, C. Hyperoxia-induced bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Better models for better therapies. Dis. Model. Mech. 2021, 14, dmm047753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczynski, B.W.; Maduekwe, E.T.; O’Reilly, M.A. The role of hyperoxia in the pathogenesis of experimental BPD. Semin. Perinatol. 2013, 37, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V.; Gruen, J.R. The genetics of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin. Perinatol. 2006, 30, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampath, V.; Garland, J.S.; Helbling, D.; Dimmock, D.; Mulrooney, N.P.; Simpson, P.M.; Murray, J.C.; Dagle, J.M. Antioxidant response genes sequence variants and BPD susceptibility in VLBW infants. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 77, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, C.; Poggi, C. The role of genetic polymorphisms in antioxidant enzymes and potential antioxidant therapies in neonatal lung disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2014, 21, 1863–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, C.V.; Ambalavanan, N. Genetic predisposition to bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin. Perinatol. 2015, 39, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golshan-Tafti, M.; Bahrami, R.; Dastgheib, S.A.; Hosein Lookzadeh, M.; Mirjalili, S.R.; Yeganegi, M.; Aghasipour, M.; Shiri, A.; Masoudi, A.; Shahbazi, A.; et al. The association between VEGF genetic variations and the risk of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1476180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvani, M.; Wilde, J.; Vitt, P.; Mailaparambil, B.; Grychtol, R.; Krueger, M.; Heinzmann, A. Association of a FGFR-4 gene polymorphism with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and neonatal respiratory distress. Dis. Markers 2013, 35, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amata, E.; Pittalà, V.; Marrazzo, A.; Parenti, C.; Prezzavento, O.; Arena, E.; Nabavi, S.M.; Salerno, L. Role of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis in bronchopulmonary dysplasia and hyperoxic lung injuries. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Hoshino, H.; Takaku, K.; Nakajima, O.; Muto, A.; Suzuki, H.; Tashiro, S.; Takahashi, S.; Shibahara, S.; Alam, J.; et al. Hemoprotein Bach1 regulates enhancer availability of heme oxygenase-1 gene. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 5216–5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Dennery, P.A.; Lin, Q.S. Disrupted postnatal lung development in heme oxygenase-1 deficient mice. Respir. Res. 2010, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Biswasa, C.; Lin, Q.S.; La, P.; Namba, F.; Zhuang, T.; Muthu, M.; Dennery, P.A. Heme oxygenase-1 regulates postnatal lung repair after hyperoxia: Role of β-catenin/hnRNPK signaling. Redox Biol. 2013, 1, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussolati, B.; Ahmed, A.; Pemberton, H.; Landis, R.C.; Di Carlo, F.; Haskard, D.O.; Mason, J.C. Bifunctional role for VEGF-induced heme oxygenase-1 in vivo: Induction of angiogenesis and inhibition of leukocytic infiltration. Blood 2004, 103, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Nagano, N.; Arai, Y.; Ogawa, R.; Kobayashi, S.; Motojima, Y.; Go, H.; Tamura, M.; Igarashi, K.; Dennery, P.; et al. Genetic ablation of Bach 1 gene enhances recovery from hyperoxic lung injury in newborn mice via transient upregulation of inflammatory genes. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 81, 926–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanimoto, T.; Hattori, N.; Senoo, T.; Furonaka, M.; Ishikawa, N.; Fujitaka, K.; Haruta, Y.; Yokoyama, A.; Igarashi, K.; Kohno, N. Genetic ablation of the Bach1 gene reduces hyperoxic lung injury in mice: Role of IL-6. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 46, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusti, B.; Vestrini, A.; Poggi, C.; Magi, A.; Pasquini, E.; Abbate, R.; Dani, C. Genetic polymorphisms of antioxidant enzymes as risk factors for oxidative stress-associated complications in preterm infants. Free Radic. Res. 2012, 46, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampath, V.; Garland, J.S.; Le, M.; Patel, A.L.; Konduri, G.G.; Cohen, J.D.; Simpson, P.M.; Hines, R.N. A TLR5 (g.1174C > T) variant that encodes a stop codon (R392X) is associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2012, 47, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachaki, S.; Daraki, A.; Polycarpou, E.; Stavropoulou, C.; Manola, K.N.; Gavrili, S. GSTP1 and CYP2B6 Genetic Polymorphisms and the Risk of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Neonates. Am. J. Perinatol. 2017, 34, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, R.D.; Jobe, A.H.; Koso-Thomas, M.; Bancalari, E.; Viscardi, R.M.; Hartert, T.V.; Ryan, R.M.; Kallapur, S.G.; Steinhorn, R.H.; Konduri, G.G.; et al. Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Executive Summary of a Workshop. J. Pediatr. 2018, 197, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qian, H.; Tao, B.; Yang, M.; Gong, J.; Yi, H.; Tang, S. The association between BACH1 polymorphisms and anti-tuberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity in a Chinese cohort. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 66, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

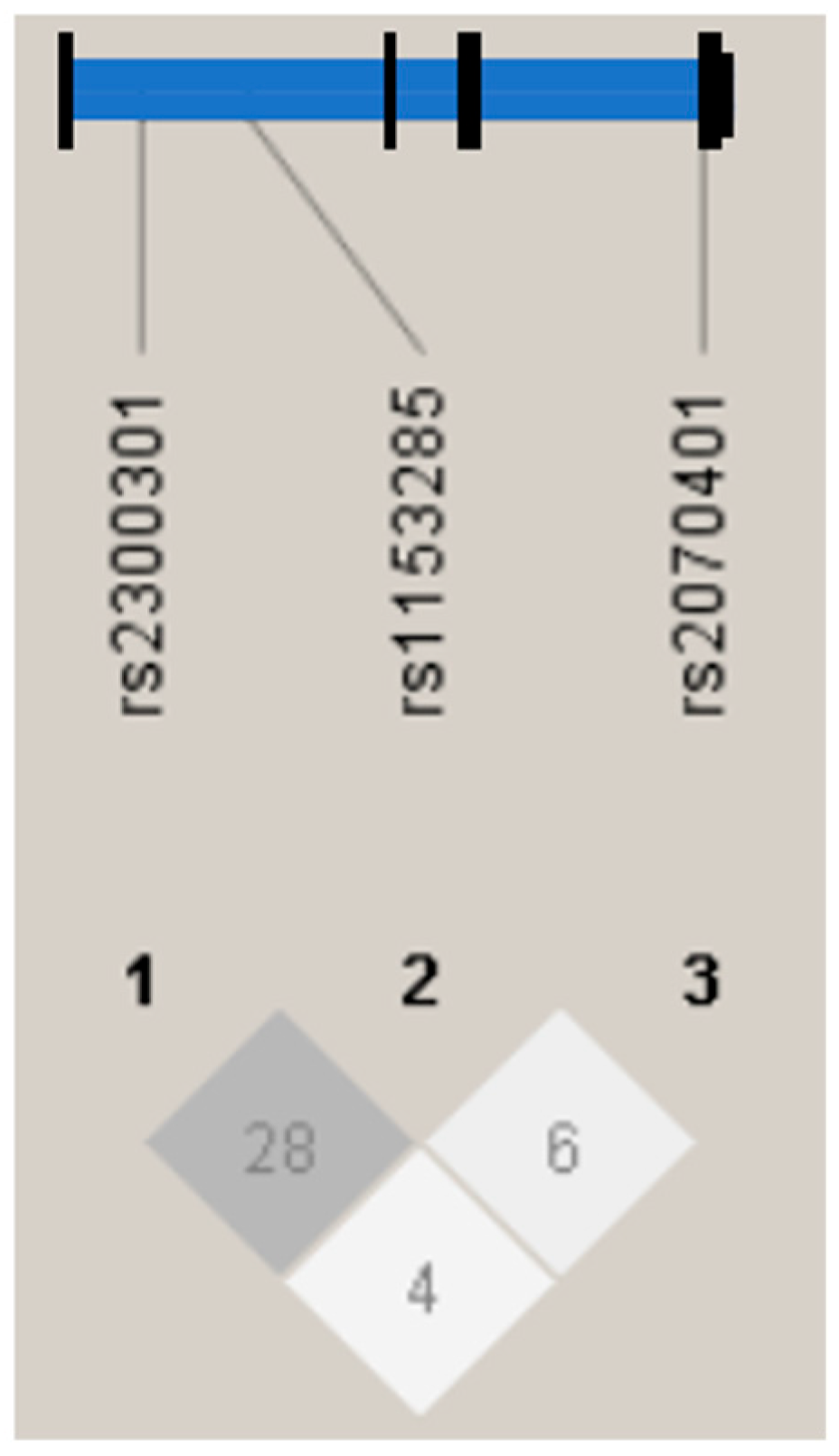

- Barrett, J.C.; Fry, B.; Maller, J.; Daly, M.J. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttner, D.M.; Dennery, P.A. Reversal of HO-1 related cytoprotection with increased expression is due to reactive iron. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 1800–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namba, F.; Go, H.; Murphy, J.A.; La, P.; Yang, G.; Sengupta, S.; Fernando, A.P.; Yohannes, M.; Biswas, C.; Wehrli, S.L.; et al. Expression level and subcellular localization of heme oxygenase-1 modulates its cytoprotective properties in response to lung injury: A mouse model. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Shindo, T.; Saigusa, D.; Kato, H.; Suzuki, K.; Sato, M.; Ishii, Y.; Shimokawa, H.; Igarashi, K. Ferroptosis is controlled by the coordinated transcriptional regulation of glutathione and labile iron metabolism by the transcription factor BACH1. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, F.; Wang, L.; Miao, L.; Wang, X. BTB and CNC homology 1 inhibition ameliorates fibrosis and inflammation via blocking ERK pathway in pulmonary fibrosis. Exp. Lung Res. 2021, 47, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanashima, K.; Mawatari, T.; Tahara, N.; Higuchi, N.; Nakaura, A.; Inamine, T.; Kondo, S.; Yanagihara, K.; Fukushima, K.; Suyama, N.; et al. Genetic variants in antioxidant pathway: Risk factors for hepatotoxicity in tuberculosis patients. Tuberculosis 2012, 92, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Jin, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, D.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Han, Y.; Wei, J. Genetic Variations rs859, rs4646, and rs372883 in the 3′-Untranslated Regions of Genes Are Associated with a Risk of IgA Nephropathy. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2019, 44, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Characteristic | SMC (n = 143) | NUIH (n = 34) | UOEH (n = 16) | ARCH (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age, mean ± SD, weeks | 26 ± 2.20 | 27 ± 1.8 | 27 ± 2.1 | 25 ± 1.5 |

| Birth weight, mean ± SD, g | 795 ± 232 | 1002 ± 1690 | 787 ± 265 | 752 ± 217 |

| Male, n (%) | 075 (52) | 13 (38) | 08 (50) | 07 (37) |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 130 (91) | 33 (97) | 09 (56) | 15 (79) |

| Death prior to 36 weeks PMA, n (%) | 000 (0) | 00 (0) | 00 (0) | 00 (0) |

| Moderate or Severe BPD, n (%) | 087 (61) | 30 (88) | 12 (75) | 16 (84) |

| HOT at discharge, n (%) | 023 (16) | 08 (24) | 06 (38) | 06 (32) |

| Clinical Characteristic | HOT | non-HOT | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 43) | (n = 169) | ||

| Maternal age, mean ± SD | 33 ± 5.0 | 33 ± 5.2 | <0.39 |

| Antenatal steroids, n (%) | 25 (58) | 107 (63) | <0.59 |

| Histological chorioamnionitis (%) | 25 (58) | 061 (36) | 0.022 |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 37 (86) | 150 (89) | <0.54 |

| Gestational age, mean ± SD, wk | 26 ± 1.7 | 27 ± 2.2 | 0.015 |

| Birth weight, mean ± SD, g | 774 ± 235 | 818 ± 233 | < 0.043 |

| Male, n (%) | 24 (56) | 79 (47) | <0.23 |

| Apgar score at 1 min | 4(1–8) | 4(0–8) | <0.27 |

| Apgar score at 5 min | 6(3–9) | 7(1–10) | <0.28 |

| Use of surfactant, n (%) | 38 (88) | 140 (83) | <0.49 |

| Moderate or Severe BPD, n (%) | 42 (98) | 103 (61) | <0.01 |

| SNPs | Genotypes | HOT (n = 43) | non-HOT (n = 169) | OR * | 95% CI | p Value ** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Freq | n | Freq | |||||

| rs2300301 | GG | 23 | 0.53 | 53 | 0.31 | 1.78 | 1.20–2.04 | 0.015 |

| GA | 15 | 0.35 | 71 | 0.42 | ||||

| AA | 5 | 0.12 | 45 | 0.27 | ||||

| rs1153285 | CC | 17 | 0.40 | 72 | 0.43 | 0.63 | 0.70–3.61 | Not significant |

| CT | 16 | 0.37 | 70 | 0.41 | ||||

| TT | 10 | 0.23 | 27 | 0.16 | ||||

| rs2070401 | AA | 26 | 0.60 | 117 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.43–3.66 | Not significant |

| AG | 12 | 0.28 | 36 | 0.21 | ||||

| GG | 5 | 0.12 | 16 | 0.10 | ||||

| SNPs | Allele | HOT (n = 43) | non-HOT (n = 169) | Total | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2300301 | A | 25 | 161 | 186 | 0.048 |

| G | 61 | 177 | 238 | ||

| rs1153285 | C | 50 | 214 | 264 | 0.421 |

| T | 36 | 124 | 160 | ||

| rs2070401 | A | 64 | 270 | 334 | 0.386 |

| G | 22 | 68 | 90 |

| Clinical Characteristic | GG/GA (n = 162) | AA (n = 50) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, mean ± SD | 33 ± 5.2 | 33 ± 5.3 | 0.84 |

| Antenatal steroids, n (%) | 99 (61) | 33 (66) | 0.53 |

| Histological chorioamnionitis (%) | 71 (44) | 17 (34) | 0.22 |

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 142 (88) | 45 (90) | 0.65 |

| Gestational age, mean ± SD, wk | 26 ± 2.2 | 27 ± 2.1 | 0.36 |

| Birth weight, mean ± SD, g | 800 ± 236 | 815 ± 237 | 0.70 |

| Male, n (%) | 79 (49) | 25 (50) | 0.88 |

| Apgar score at 1 min | 4(0–8) | 4(0–8) | 0.68 |

| Apgar score at 5 min | 7(1–10) | 7(3–9) | 0.85 |

| Use of surfactant, n (%) | 138 (85) | 040 (80) | 0.38 |

| Moderate or Severe BPD, n (%) | 112 (69) | 032 (64) | 0.50 |

| Home oxygen therapy at discharge, n (%) | 38 (23) | 005 (10) | 0.04 |

| Risk Factors | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower gestational age | 1.19 | 0.99–1.42 | 0.051 |

| Male | 1.68 | 0.83–3.40 | 0.146 |

| Histological chorioamnionitis | 1.25 | 0.93–3.83 | 0.080 |

| GG or GA genotypes at rs2300301 | 2.48 | 0.90–6.80 | 0.079 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sakuraba, S.; Noguchi, A.; Arai, H.; Sasaki, A.; Haga, M.; Iwatani, A.; Nishimura, E.; Nagano, N.; Suga, S.; Araki, S.; et al. Association of Bach1 Gene Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants. Biomedicines 2026, 14, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010017

Sakuraba S, Noguchi A, Arai H, Sasaki A, Haga M, Iwatani A, Nishimura E, Nagano N, Suga S, Araki S, et al. Association of Bach1 Gene Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants. Biomedicines. 2026; 14(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010017

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakuraba, Satomi, Atsuko Noguchi, Hirokazu Arai, Ayumi Sasaki, Mitsuhiro Haga, Ayaka Iwatani, Eri Nishimura, Nobuhiko Nagano, Shutaro Suga, Shunsuke Araki, and et al. 2026. "Association of Bach1 Gene Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants" Biomedicines 14, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010017

APA StyleSakuraba, S., Noguchi, A., Arai, H., Sasaki, A., Haga, M., Iwatani, A., Nishimura, E., Nagano, N., Suga, S., Araki, S., Konishi, A., Onouchi, Y., Ito, M., & Namba, F. (2026). Association of Bach1 Gene Polymorphisms with Susceptibility to Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia in Preterm Infants. Biomedicines, 14(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines14010017