Long-Term Outcomes of First-Line Anti-TNF Therapy for Chronic Inflammatory Pouch Conditions: A Multi-Centre Multi-National Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Undergone ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) with formation of a J-pouch for ulcerative colitis (UC);

- Evidence of chronic inflammatory pouch condition on endoscopic assessment, with inflammation confirmed histologically;

- Received antibiotic therapy prior to starting anti-TNF treatment;

- Diagnosed with chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis (CARP);

- Treated with at least one dose of infliximab (IFX) or adalimumab (ADA) for post-colectomy chronic inflammatory pouch condition;

- No other post-colectomy biologic treatments before initiating anti-TNF therapy;

- Minimum follow-up of one year after anti-TNF treatment initiation;

- One of the following reported outcomes within the last two months of their final IFX infusion or the last two weeks of their final ADA injection:

- ○

- Pouch failure, defined as the need for a defunctioning ileostomy;

- ○

- Switch to another advanced inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) medication (either an in-class switch to another anti-TNF or a switch to a different drug class) due to lack of efficacy (either primary non-response or secondary loss of response);

- ○

- Discontinuation of anti-TNF due to antibody formation, allergic reaction, treatment-related adverse events, or safety concerns;

- ○

- Advised to continue anti-TNF therapy at the last infusion or injection.

- Patients who underwent IPAA for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Crohn’s disease;

- Patients lost to follow-up.

Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Anti-TNF Discontinuation

3.3. Second-Line Therapy Outcomes

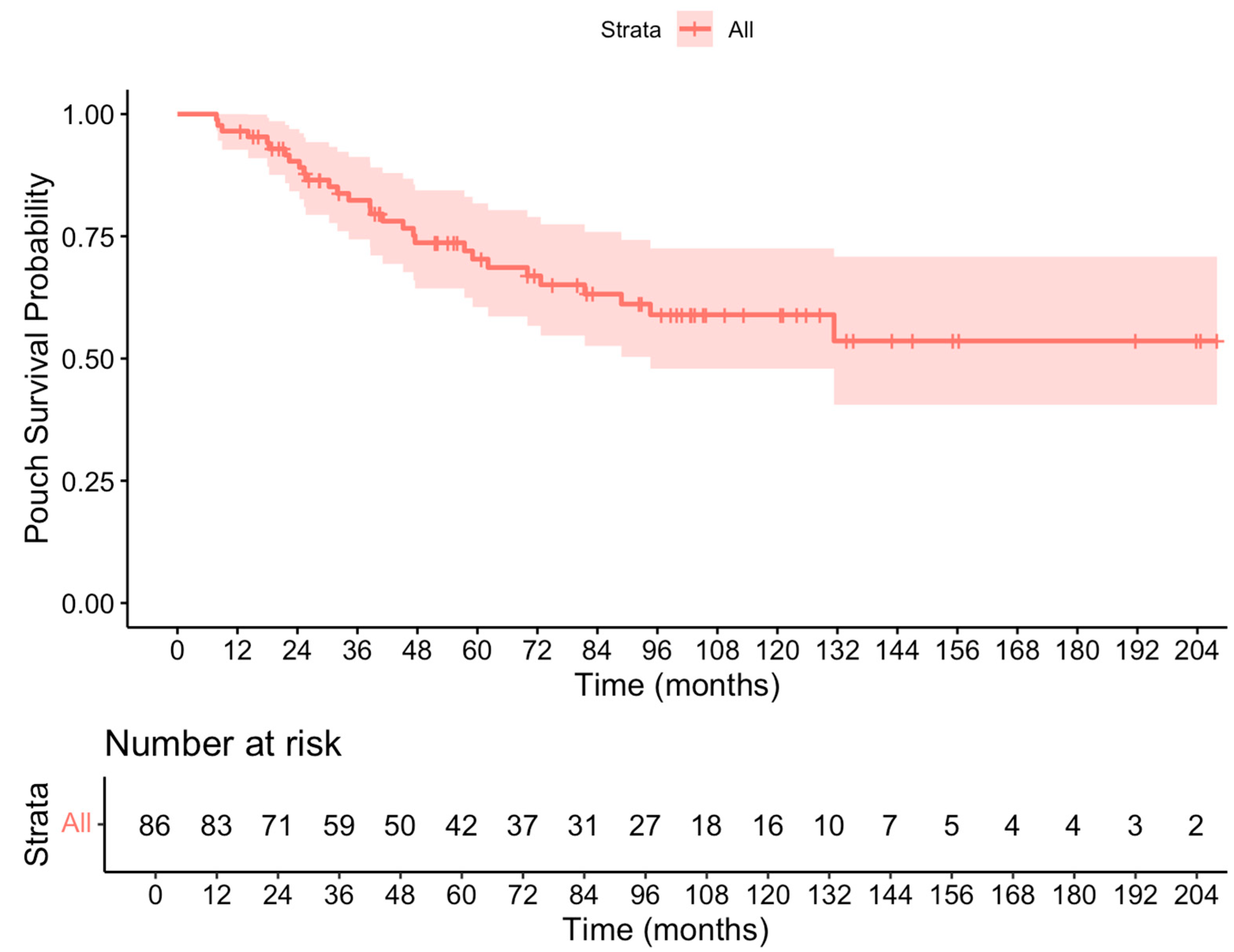

3.4. Pouch Failure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Spinelli, A.; Bonovas, S.; Burisch, J.; Kucharzik, T.; Adamina, M.; Annese, V.; Bachmann, O.; Bettenworth, D.; Chaparro, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Ulcerative Colitis: Surgical Treatment. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simchuk, E.J.; Thirlby, R.C. Risk factors and true incidence of pouchitis in patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. World J. Surg. 2000, 24, 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightner, A.L.; Mathis, K.L.; Dozois, E.J.; Hahnsloser, D.; Loftus, E.V., Jr.; Raffals, L.E.; Pemberton, J.H. Results at up to 30 Years After Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis for Chronic Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. Pouchitis: What every gastroenterologist needs to know. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 1538–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, D.S.; Shen, B. Endoscopy in the management of patients after ileal pouch surgery for ulcerative colitis. Endoscopy 2008, 40, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shen, B. Crohn’s disease of the pouch: Diagnosis and management. Expert. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 3, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini Kadijani, A.; Javadinia, F.; Mirzaei, A.; Khazaei Koohpar, Z.; Balaii, H.; Baradaran Ghavami, S.; Gholamrezaei, Z.; Asadzadeh-Aghdaei, H. Apoptosis markers of circulating leukocytes are associated with the clinical course of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2018, 11 (Suppl. S1), S53–S58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Madden, M.V.; McIntyre, A.S.; Nicholls, R.J. Double-blind crossover trial of metronidazole versus placebo in chronic unremitting pouchitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1994, 39, 1193–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gionchetti, P.; Rizzello, F.; Venturi, A.; Ugolini, F.; Rossi, M.; Brigidi, P.; Johansson, R.; Ferrieri, A.; Poggioli, G.; Campieri, M. Antibiotic combination therapy in patients with chronic, treatment-resistant pouchitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 13, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, J.P.; Ding, N.S.; Worley, G.; Mclaughlin, S.; Preston, S.; Faiz, O.D.; Clark, S.K.; Hart, A.L. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The management of chronic refractory pouchitis with an evidence-based treatment algorithm. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardi, D.S.; D’Haens, G.; Shen, B.; Campbell, S.; Gionchetti, P. Clinical guidelines for the management of pouchitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischman, M.; Godny, L.; Friedenberg, A.; Barkan, R.; White, I.; Wasserberg, N.; Rabinowitz, K.; Avni-Biron, I.; Banai, H.; Snir, Y.; et al. Factors Associated with Biologic Therapy After Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 31, izae272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, S.; Silverberg, M.S.; Danese, S.; Gionchetti, P.; Löwenberg, M.; Jairath, V.; Feagan, B.G.; Bressler, B.; Ferrante, M.; Hart, A.; et al. Vedolizumab for the Treatment of Chronic Pouchitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstockt, B.; Claeys, C.; De Hertogh, G.; Van Assche, G.; Wolthuis, A.; D’Hoore, A.; Vermeire, S.; Ferrante, M. Outcome of biological therapies in chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis: A retrospective single-centre experience. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Lopez, R.; Queener, E.; Shen, B. Adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease of the ileal pouch. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M.; D’Haens, G.; Dewit, O.; Baert, F.; Holvoet, J.; Geboes, K.; De Hertogh, G.; Van Assche, G.; Vermeire, S.; Rutgeerts, P.; et al. Efficacy of infliximab in refractory pouchitis and Crohn’s disease-related complications of the pouch: A Belgian case series. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Remzi, F.H.; Lavery, I.C.; Lopez, R.; Queener, E.; Shen, L.; Goldblum, J.; Fazio, V.W. Administration of adalimumab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease of the ileal pouch. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herfarth, H.H.; Long, M.D.; Isaacs, K.L. Use of Biologics in Pouchitis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 49, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, J.P.; Penez, L.; Mohsen Elkady, S.; Worley, G.H.T.; McLaughlin, S.D.; Mullish, B.H.; Quraishi, M.N.; Ding, N.S.; Glyn, T.; Kandiah, K.; et al. Long term outcomes of initial infliximab therapy for inflammatory pouch pathology: A multi-Centre retrospective study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 1051–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Tremaine, W.J.; Batts, K.P.; Pemberton, J.H.; Phillips, S.F. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: A Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1994, 69, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viazis, N.; Giakoumis, M.; Koukouratos, T.; Anastasiou, J.; Katopodi, K.; Kechagias, G.; Tribonias, G.; Karamanolis, D. Long term benefit of one year infliximab administration for the treatment of chronic refractory pouchitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2013, 7, e457–e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, O.B.; Rosenberg, M.; Tyler, A.D.; Stempak, J.M.; Steinhart, A.H.; Cohen, Z.; Greenberg, G.R.; Silverberg, M.S. Infliximab to Treat Refractory Inflammation After Pelvic Pouch Surgery for Ulcerative Colitis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2016, 10, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiu, T.H.; Ko, Y.; Pudipeddi, A.; Natale, P.; Leong, R.W. Meta-analysis: Persistence of advanced therapies in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 59, 1312–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, J.P.; Rottoli, M.; Felwick, R.K.; Worley, G.H.; McLaughlin, S.D.; Vallicelli, C.; Bassett, P.; Faiz, O.D.; Hart, A.L.; Clark, S.K. Biological therapy for the treatment of prepouch ileitis: A retrospective observational study from three centers. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, J.P.; McLaughlin, S.D.; Faiz, O.D.; Hart, A.L.; Clark, S.K. Incidence and Long-term Implications of Prepouch Ileitis: An Observational Study. Dis. Colon. Rectum. 2018, 61, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandan, S.; Mohan, B.P.; Kumar, A.; Khan, S.R.; Chandan, O.C.; Kassab, L.L.; Ponnada, S.; Kochhar, G.S. Safety and Efficacy of Biological Therapy in Chronic Antibiotic Refractory Pouchitis: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 55, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Middleton, S.; Márquez, J.R.; Scott, B.B.; Flint, L.; van Hoogstraten, H.J.; Chen, A.C.; Zheng, H.; Danese, S.; et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 392–400.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombel, J.F.; Sandborn, W.J.; Reinisch, W.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Kornbluth, A.; Rachmilewitz, D.; Lichtiger, S.; D’Haens, G.; Diamond, R.H.; Broussard, D.L.; et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnloser, D.; Pemberton, J.H.; Wolff, B.G.; Larson, D.R.; Crown-hart, B.S.; Dozois, R.R. Results at up to 20 years after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Br. J. Surg. 2007, 94, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulchinsky, H.; Hawley, P.R.; Nicholls, J. Long-term failure after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Ann. Surg. 2003, 238, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, V.W.; Ziv, Y.; Church, J.M.; Oakley, J.R.; Lavery, I.C.; Milsom, J.W.; Schroeder, T.K. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann. Surg. 1995, 222, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stallmach, A.; Hagel, S.; Bruns, T. Adverse effects of biologics used for treating IBD. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2010, 24, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaitre, M.; Kirchgesner, J.; Rudnichi, A.; Carrat, F.; Zureik, M.; Carbonnel, F.; Dray-Spira, R. Association Between Use of Thiopurines or Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists Alone or in Combination and Risk of Lymphoma in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. JAMA 2017, 318, 1679–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchgesner, J.; Lemaitre, M.; Carrat, F.; Zureik, M.; Carbonnel, F.; Dray-Spira, R. Risk of Serious and Opportunistic Infections Associated with Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 337–346.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrinton, L.J.; Liu, L.; Weng, X.; Lewis, J.D.; Hutfless, S.; Allison, J.E. Role of thiopurine and anti-TNF therapy in lymphoma in inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honap, S.; Caron, B.; Ollech, J.E.; Fischman, M.; Papamichael, K.; De Jong, D.; Gecse, K.B.; Centritto, A.; Samaan, M.A.; Irving, P.M.; et al. Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor Drug Concentration Is Not Associated with Disease Outcomes in Pouchitis: A Retrospective, International Study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2025, 70, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | n = 98 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 51.3 (37.5–65.1) |

| Age at UC diagnosis (years) | 24 (13.5–34.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 77/98 (78.6%) |

| Middle Eastern | 9/98 (9.2%) |

| South Asian | 12/98 (12.2%) |

| Females | 45/98 (45.9%) |

| Smoking | 12/98 (12.2%) |

| PSC | 4/98 (4.1%) |

| Colectomy indication | |

| Refractory disease | 90/97 (92.8%) |

| Dysplasia | 7/97 (7.2%) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Anti-TNF treatment prior to colectomy | |

| Yes | 9/88 (10.2%) |

| No | 79/88 (89.8%) |

| Missing | 10 |

| Small bowel strictures | 45/98 (45.9%) |

| Cuffitis | 14/98 (14.3%) |

| Fistulae | 20/98 (20.4%) |

| Anti-TNF indication | |

| Isolated PPI | 7/98 (7.1%) |

| PPI and pouchitis | 66/98 (67.3%) |

| Isolated pouchitis | 25/98 (25.6%) |

| First-line Anti-TNF | |

| ADA | 35/98 (35.7%) |

| IFX | 63/98 (64.3%) |

| Combo or monotherapy | |

| Combo | 27/84 (32.1%) |

| Monotherapy | 57/84 (67.9%) |

| Missing | 14 |

| Infliximab | Adalimumab | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 63 | 35 | |

| Discontinuation rate | 50/63 (79.4%) | 26/35 (74.3%) | p = 0.019 |

| Pouch failure rate | 23/63 (36.5%) | 10/35 (31.4%) | p = 0.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghersin, I.; Fischman, M.; Calini, G.; Koifman, E.; Celentano, V.; Segal, J.P.; Argyriou, O.; McLaughlin, S.D.; Johnson, H.; Rottoli, M.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of First-Line Anti-TNF Therapy for Chronic Inflammatory Pouch Conditions: A Multi-Centre Multi-National Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081870

Ghersin I, Fischman M, Calini G, Koifman E, Celentano V, Segal JP, Argyriou O, McLaughlin SD, Johnson H, Rottoli M, et al. Long-Term Outcomes of First-Line Anti-TNF Therapy for Chronic Inflammatory Pouch Conditions: A Multi-Centre Multi-National Study. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(8):1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081870

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhersin, Itai, Maya Fischman, Giacomo Calini, Eduard Koifman, Valerio Celentano, Jonathan P. Segal, Orestis Argyriou, Simon D. McLaughlin, Heather Johnson, Matteo Rottoli, and et al. 2025. "Long-Term Outcomes of First-Line Anti-TNF Therapy for Chronic Inflammatory Pouch Conditions: A Multi-Centre Multi-National Study" Biomedicines 13, no. 8: 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081870

APA StyleGhersin, I., Fischman, M., Calini, G., Koifman, E., Celentano, V., Segal, J. P., Argyriou, O., McLaughlin, S. D., Johnson, H., Rottoli, M., Sahnan, K., Warusavitarne, J., & Hart, A. L. (2025). Long-Term Outcomes of First-Line Anti-TNF Therapy for Chronic Inflammatory Pouch Conditions: A Multi-Centre Multi-National Study. Biomedicines, 13(8), 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13081870