Managing Urethral Diverticulum During Pregnancy Utilizing Advanced Ultrasonographic Techniques: A Literature Review and Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

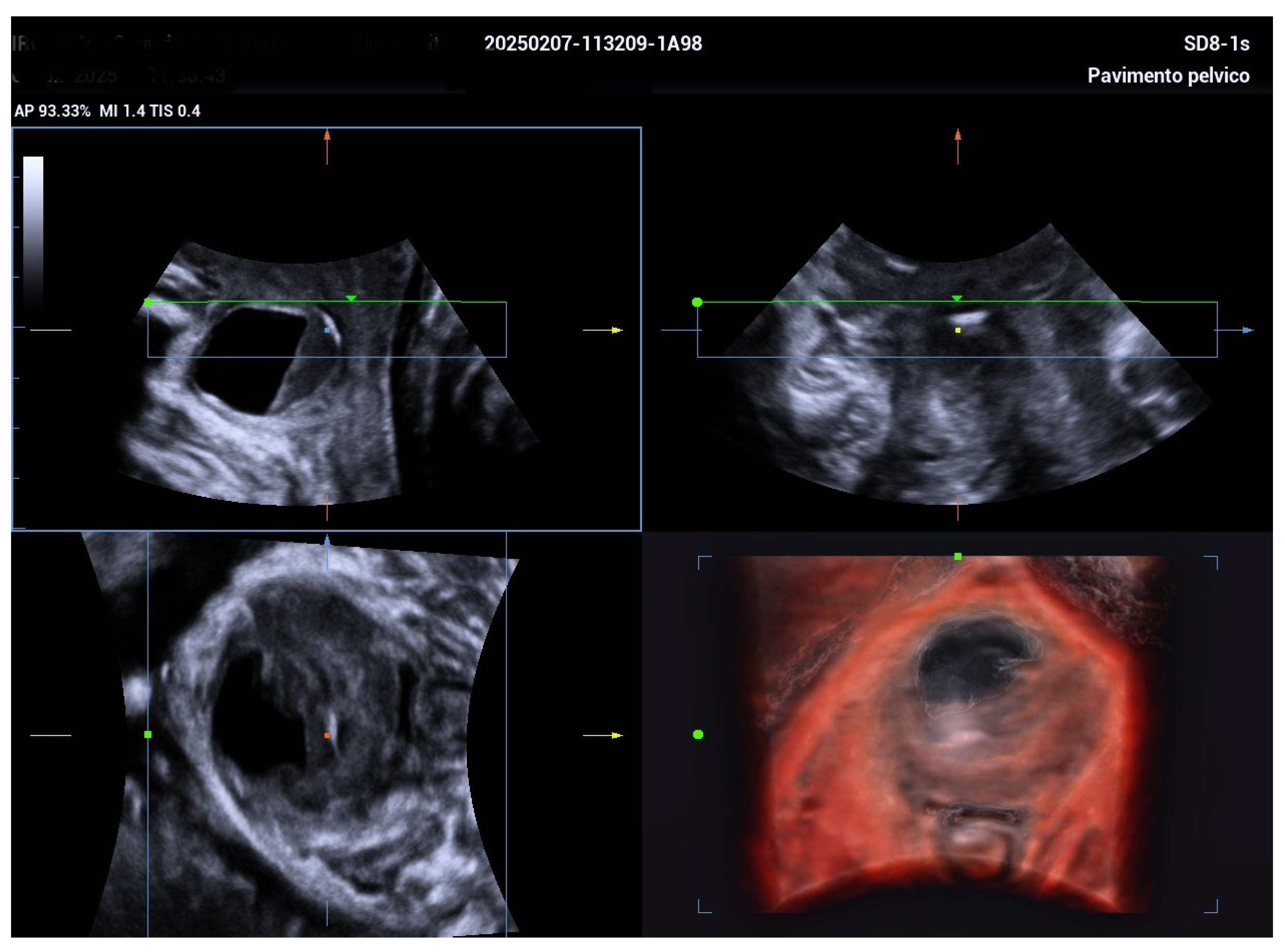

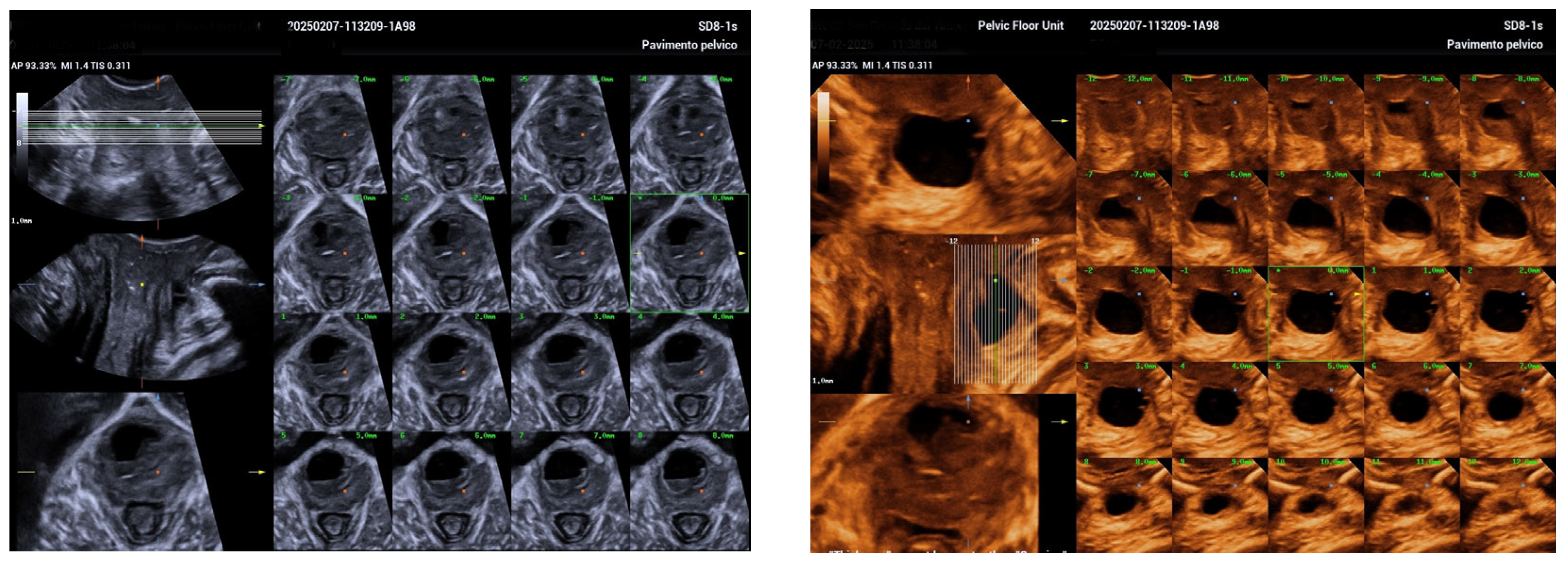

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

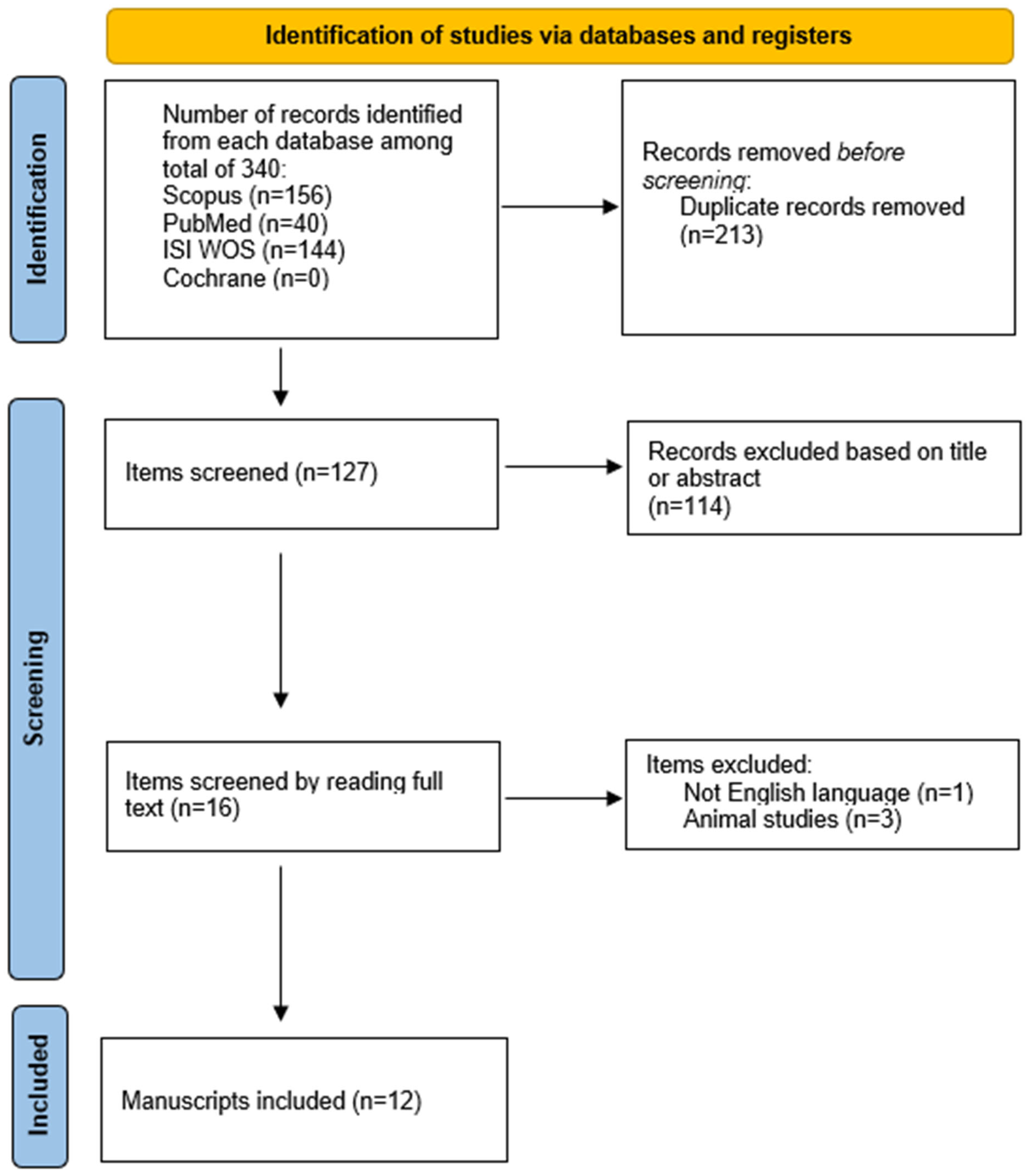

4. Literature Review

4.1. Clinical Presentation

4.2. Diverticulum Size

4.3. Diagnostic Approach

4.4. Management During Pregnancy

4.5. Mode of Delivery

4.6. Postpartum Intervention

4.7. Future Directions and Clinical Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Nashar, S.A.; Singh, R.; Bacon, M.M.; Kim-Fine, S.; Occhino, J.A.; Gebhart, J.B.; Klingele, C.J. Female urethral diverticulum: Presentation, diagnosis, and predictors of outcomes after surgery. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 22, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Foley, C.L.; Greenwell, T.J.; Gardiner, R.A. Urethral diverticula in females. BJU Int. 2011, 108 (Suppl. S2), 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antosh, D.D.; Gutman, R.E. Diagnosis and management of female urethral diverticulum. Female Pelvic Med. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 17, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirpiris, A.; Chan, G.; Chaulk, R.C.; Tran, H.; Liu, M. An update on urethral diverticula: Results from a large case series. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2022, 16, E443–E447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jeong, S.; Kim, J.; Song, C.; Lee, S.H.; Ahn, J.W.; Lee, S.J.; Roh, H.J.; Moon, K.H.; Kim, J.S. Urethral diverticulum in pregnancy: Rare case report and brief literature review. Taiwan J. Obs. Gynecol. 2024, 63, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.; Minassian, V.A. Resection of urethral diverticulum in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122 Pt 2, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, P.A.; Carey, M.P.; Dwyer, P.L. Urethral diverticula in pregnancy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obs. Gynaecol. 1998, 38, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artis, K.; Sivanesan, K.; Veerasingham, M. A persistent urethral diverticulum in pregnancy: Case report and review of the literature. Case Rep. Womens Health 2020, 26, e00189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wittich, A.C. Excision of urethral diverticulum calculi in a pregnant patient on an outpatient basis. J. Am. Osteopat. Assoc. 1997, 97, 461–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Carswell, F.M. Urethral diverticulum in pregnancy: A case report. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 2149–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.-X.; Lo, T.-S.; Wu, P.-Y.; Pue, L.B.; Karim, N.b. Urethral diverticulum in pregnancy. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2015, 4, 47–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magann, E.F.; Newton, L.S.; Barr, S.A. Urethral diverticulum presenting as a large vaginal mass complicating pregnancy and delivery. Am. J. Case Rep. 2017, 18, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Aoun, R.; Hermieu, N.; Schoentgen, N.; Xylinas, E.; Hermieu, J.F.; Ouzaid, I. Urethral Diverticulum During Pregnancy Managed with Primum Non Nocere Principle: Conservative Treatment During Pregnancy and Diverticulectomy After Child Birth. Urology 2023, 180, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, M.J. Role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of urethral diverticulum during pregnancy. J. Obstet. Imaging 2022, 15, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.S.; Chen, W.T.; Huang, C.C. MRI evaluation of urethral diverticulum in pregnant patients: Implications for delivery planning. Int. J. Women’s Health Imaging 2023, 8, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gatta, G.; Di Grezia, G.; Cuccurullo, V.; Sardu, C.; Iovino, F.; Comune, R.; Ruggiero, A.; Chirico, M.; La Forgia, D.; Fanizzi, A.; et al. MRI in Pregnancy and Precision Medicine: A Review from Literature. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Case Reference | Clinical Presentation | Diverticulum Size | Diagnostic Approach (Gestational Week) | Management During Pregnancy | Mode of Delivery (Gestational Week) | Postpartum Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iyer et al. [6] | Asymptomatic anterior vaginal mass | 3–4 cm | TVUS at 30 + 2 weeks | Surgical excision at 31 + 2 weeks (spinal anesthesia) | Cesarean at 39 weeks (to prevent fistula) | No recurrence reported |

| Moran et al. [7]—Case 1 | Urethral discomfort | 1.2 cm | TVUS (2nd trimester) | Antibiotics | Vaginal delivery (week not specified) | Diverticulectomy |

| Moran et al. [7]—Case 2 | Asymptomatic | Not available | Clinical suspicion at 30 weeks | Expectant management | Cesarean at 38 weeks | Diverticulectomy |

| Moran et al. [7]—Case 3 | Asymptomatic | 3 cm | Not reported | Needle aspiration | Repeat cesarean | Diverticulectomy |

| Moran et al. [7]—Case 4 | Hematuria | 6 cm | TVUS at 30 weeks | Conservative; aspiration during labor | Vaginal delivery | Diverticulectomy |

| Moran et al. [7]—Case 5 | Dysuria, urinary frequency | 4 cm | Cystourethroscopy at 6 weeks | Antibiotics, incision and drainage | Cesarean at 37 weeks | Continued I&D post-delivery |

| Artis et al. [8] | Recurrent symptoms over 3 pregnancies | 1–2 cm (range) | TVUS (26–33 weeks) | Conservative/lithotripsy/stents | Three vaginal deliveries | Diverticulectomy after 3rd pregnancy |

| Wittich [9] | Tender swelling, dyspareunia | Not available | Pelvic exam at 19 weeks | Surgical removal of UD calculi | Not documented | No recurrence reported |

| Carswell [10] | Severe pelvic pain | 2 cm | MRI at 11 weeks | Cystoscopic drainage | Vaginal at 37 weeks | Diverticulectomy |

| Xie et al. [11] | Asymptomatic vaginal mass | 2 cm | Aspiration at 14 weeks | Antibiotics and aspiration | Attempted vaginal → cesarean (labor failure) | Diverticulectomy |

| Magann et al. [12] | Incidental finding | ~5 cm | TVUS at 38 + 4 weeks | Conservative observation | Cesarean at 39 weeks | Reconstructive surgery |

| Jeong et al. [5] | Suprapubic pain, purulent discharge, leakage | 5.5 cm | TVUS, TPUS, 3D ultrasound at 34 weeks | Antibiotics; aspiration considered | Planned vaginal delivery | Postpartum diverticulectomy |

| Aoun et al. [13] | UTI (58%), purulent discharge (50%), bulging/dyspareunia (33%) | Median 24.6 mm (12–34 mm) | MRI (100%), TVUS (rare), VCUG (33%) | Conservative; UDp milking in 2 cases | 11 vaginal, 1 emergency C-section (fetal bradycardia) | Diverticulectomy 3 months postpartum |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Vicari, D.; Barba, M.; Cola, A.; Frigerio, M. Managing Urethral Diverticulum During Pregnancy Utilizing Advanced Ultrasonographic Techniques: A Literature Review and Case Study. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061432

De Vicari D, Barba M, Cola A, Frigerio M. Managing Urethral Diverticulum During Pregnancy Utilizing Advanced Ultrasonographic Techniques: A Literature Review and Case Study. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(6):1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061432

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Vicari, Desirèe, Marta Barba, Alice Cola, and Matteo Frigerio. 2025. "Managing Urethral Diverticulum During Pregnancy Utilizing Advanced Ultrasonographic Techniques: A Literature Review and Case Study" Biomedicines 13, no. 6: 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061432

APA StyleDe Vicari, D., Barba, M., Cola, A., & Frigerio, M. (2025). Managing Urethral Diverticulum During Pregnancy Utilizing Advanced Ultrasonographic Techniques: A Literature Review and Case Study. Biomedicines, 13(6), 1432. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061432