Comparative Evaluation of Analgesics in a Murine Bile Duct Ligation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

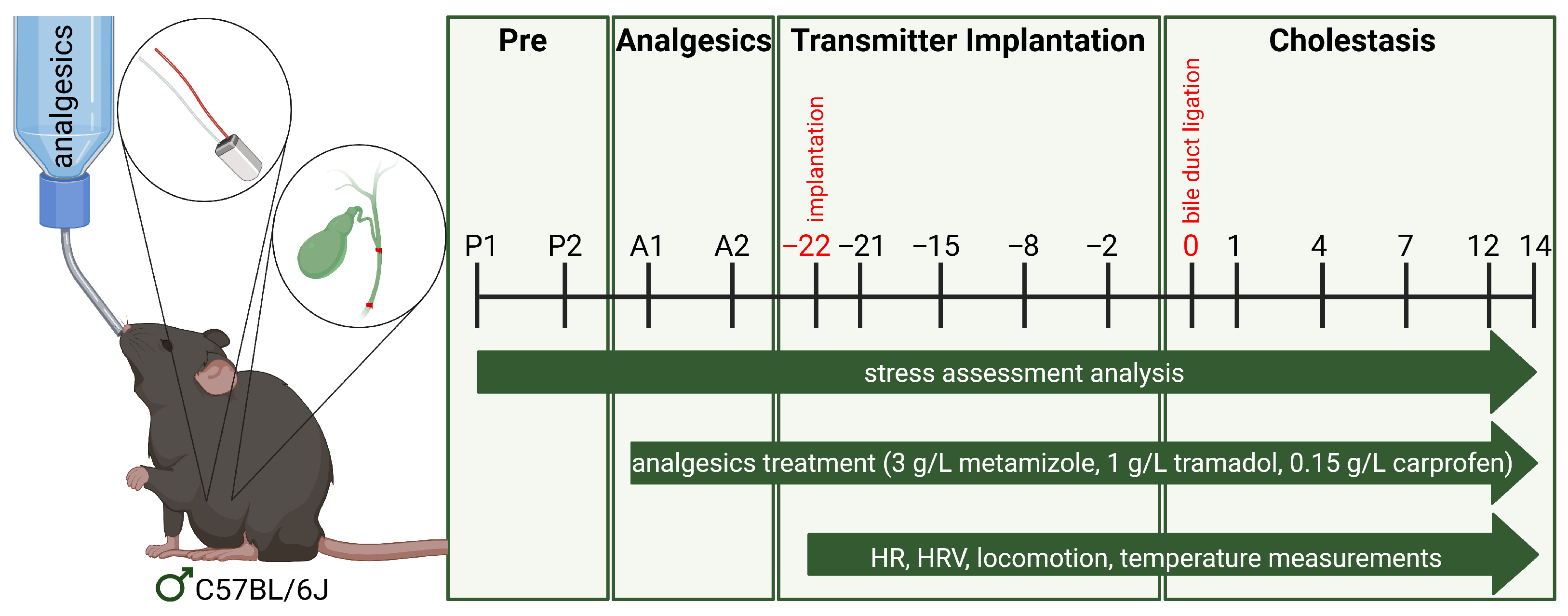

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Animal Subjects

2.3. Assessment of Well-Being

2.4. Analgesic Preparation

2.5. Transmitter Implantation and Data Acquisition

2.6. Induction of Cholestasis

2.7. Evaluation of Blood and Tissue

2.8. Data Analyses

3. Results

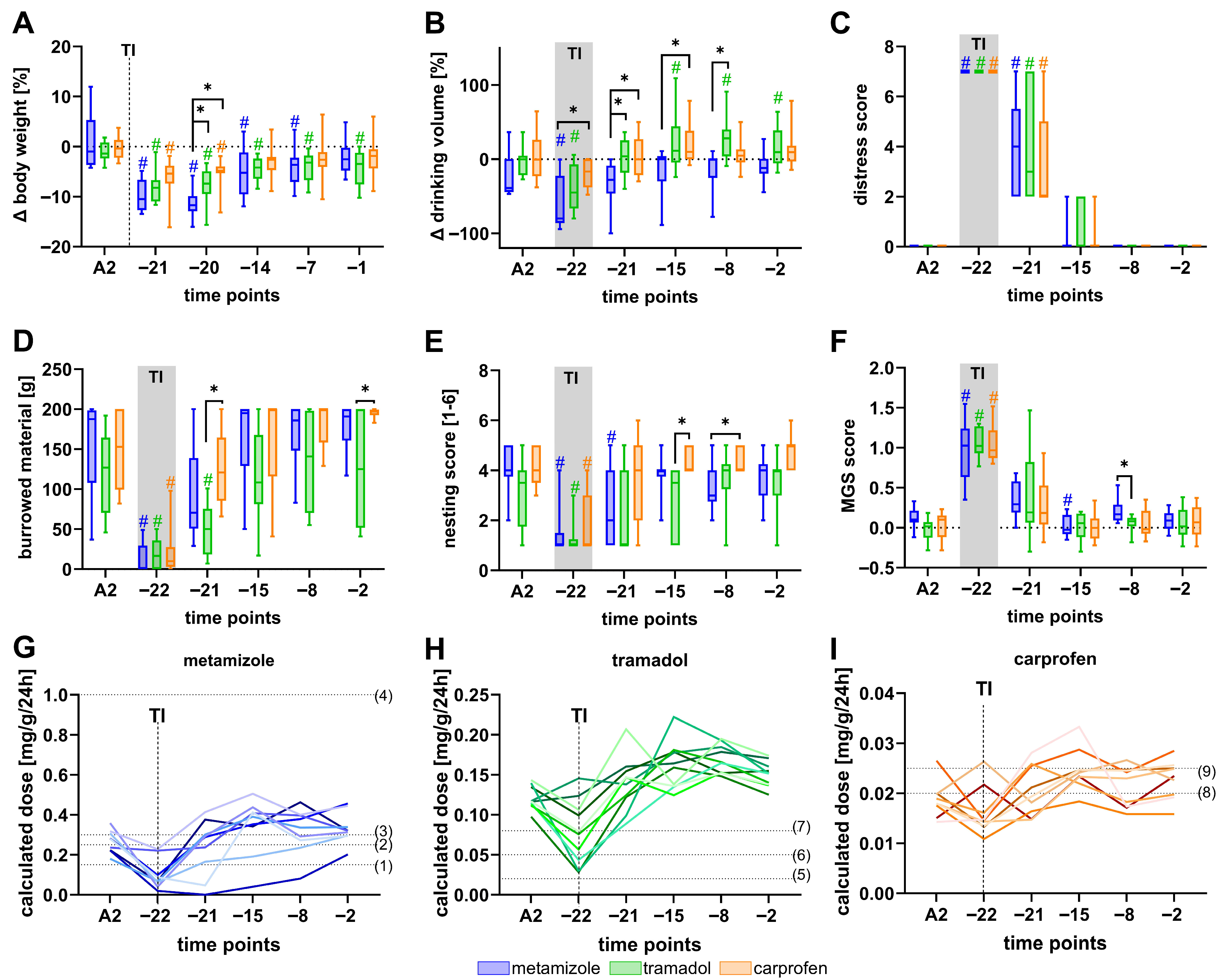

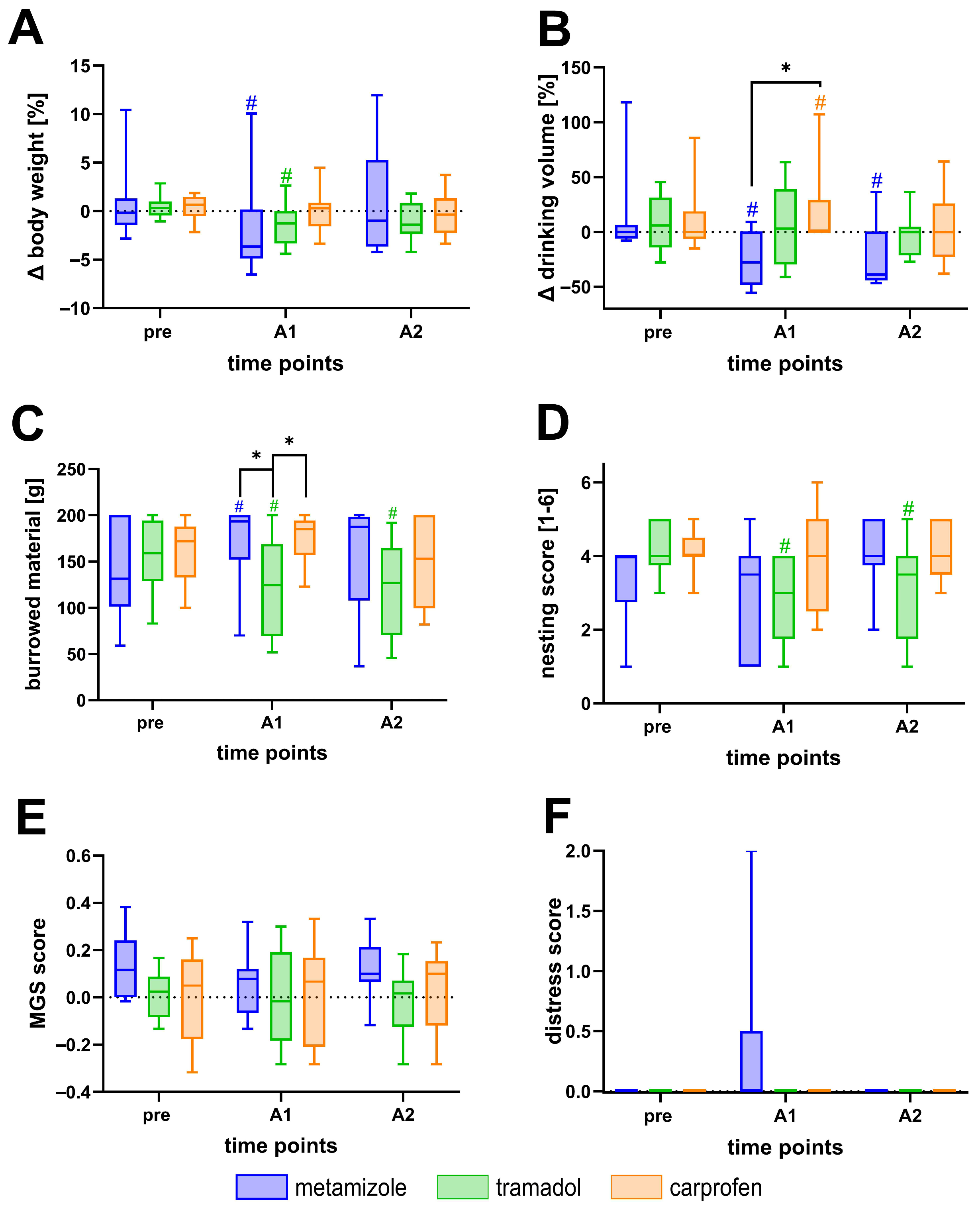

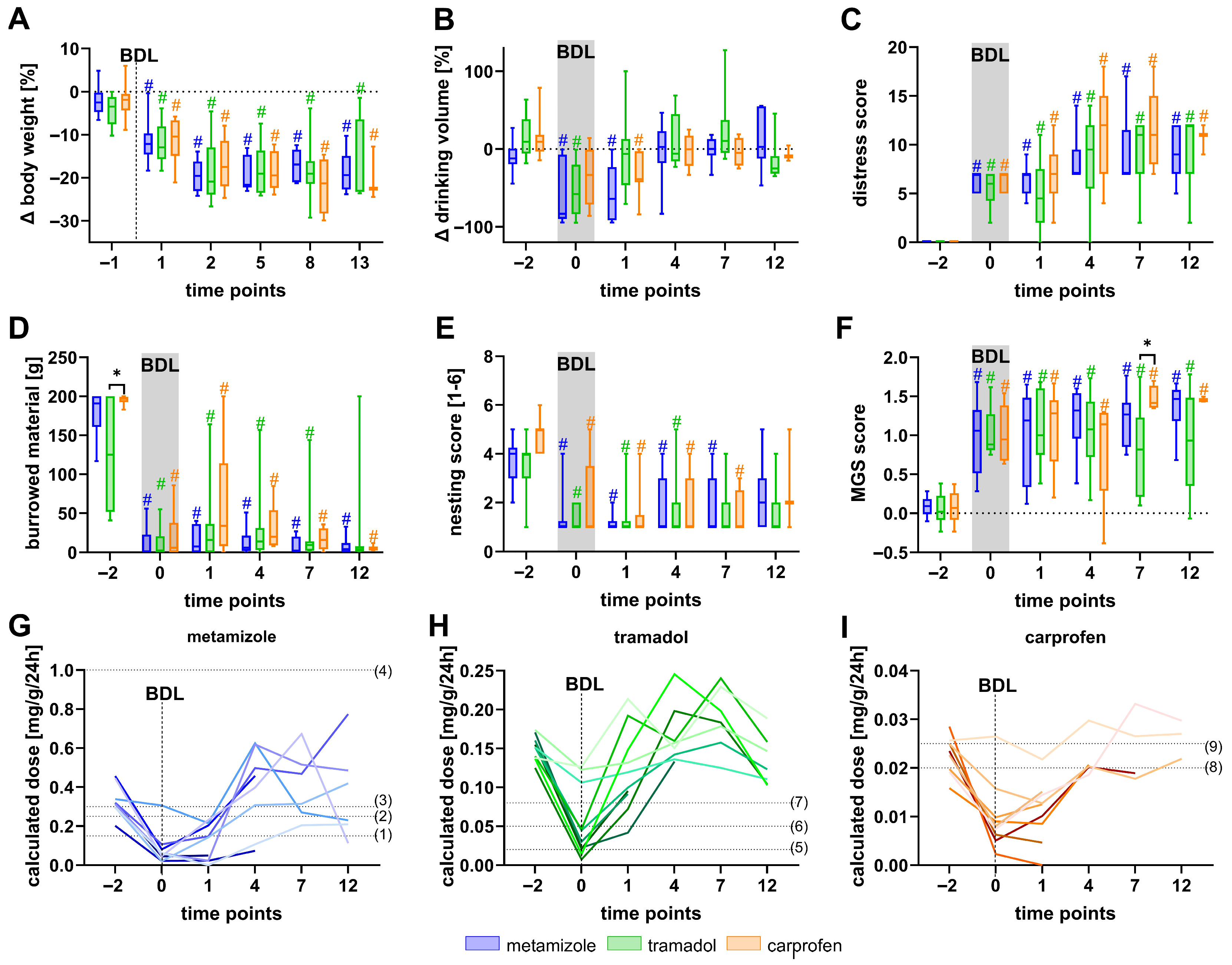

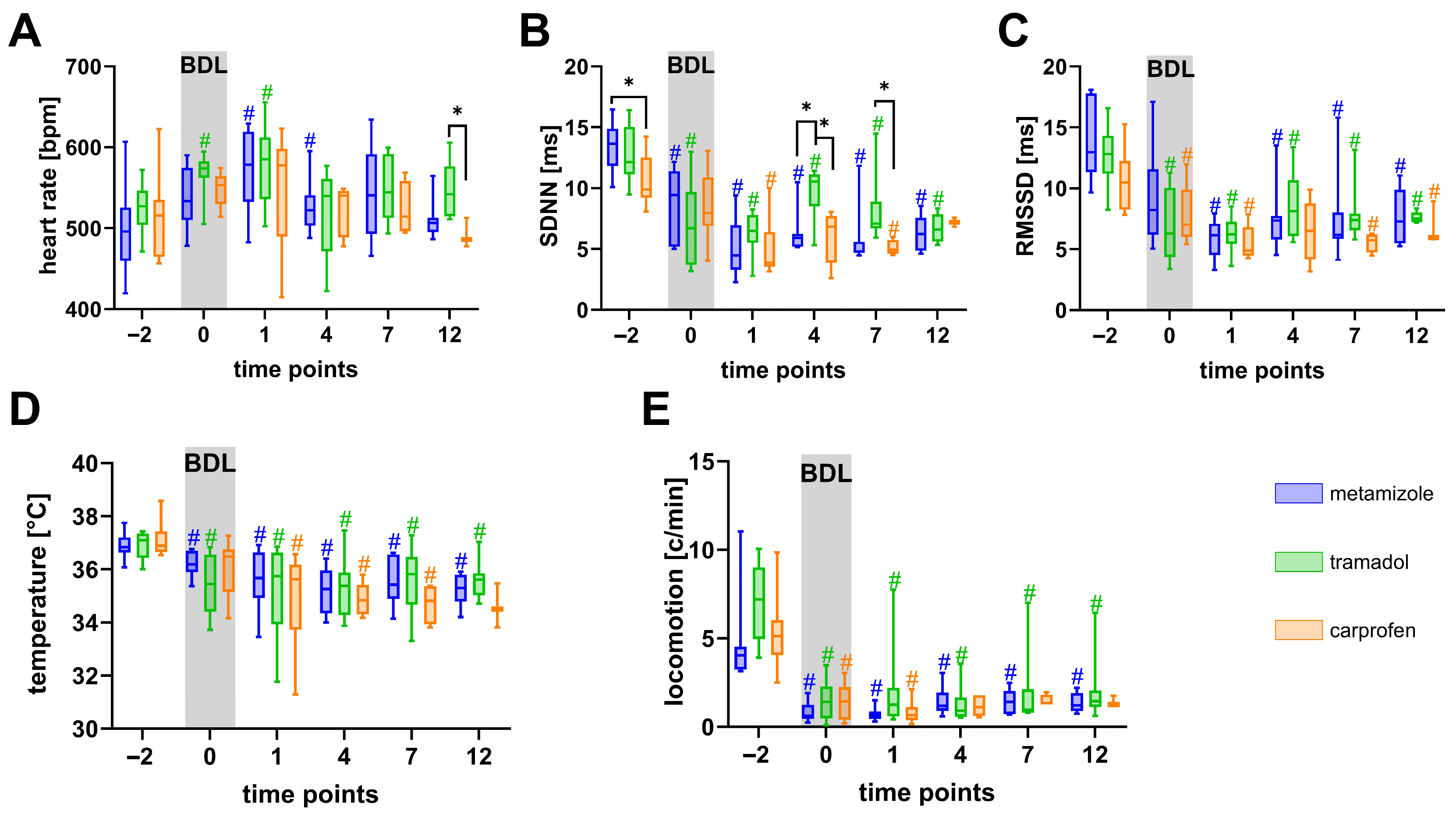

3.1. Effects of Metamizole, Tramadol, and Carprofen on Welfare Parameters in Healthy Mice

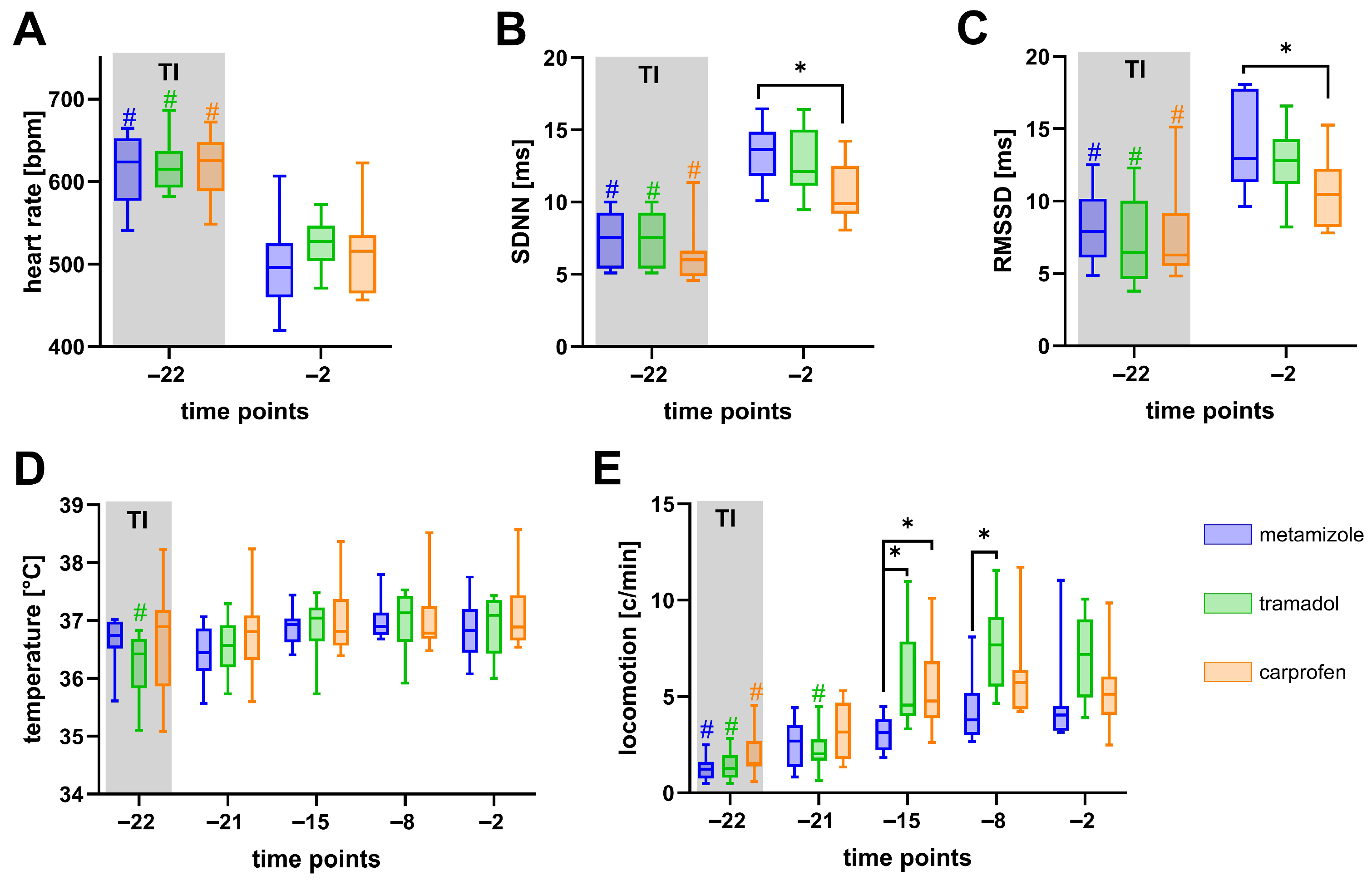

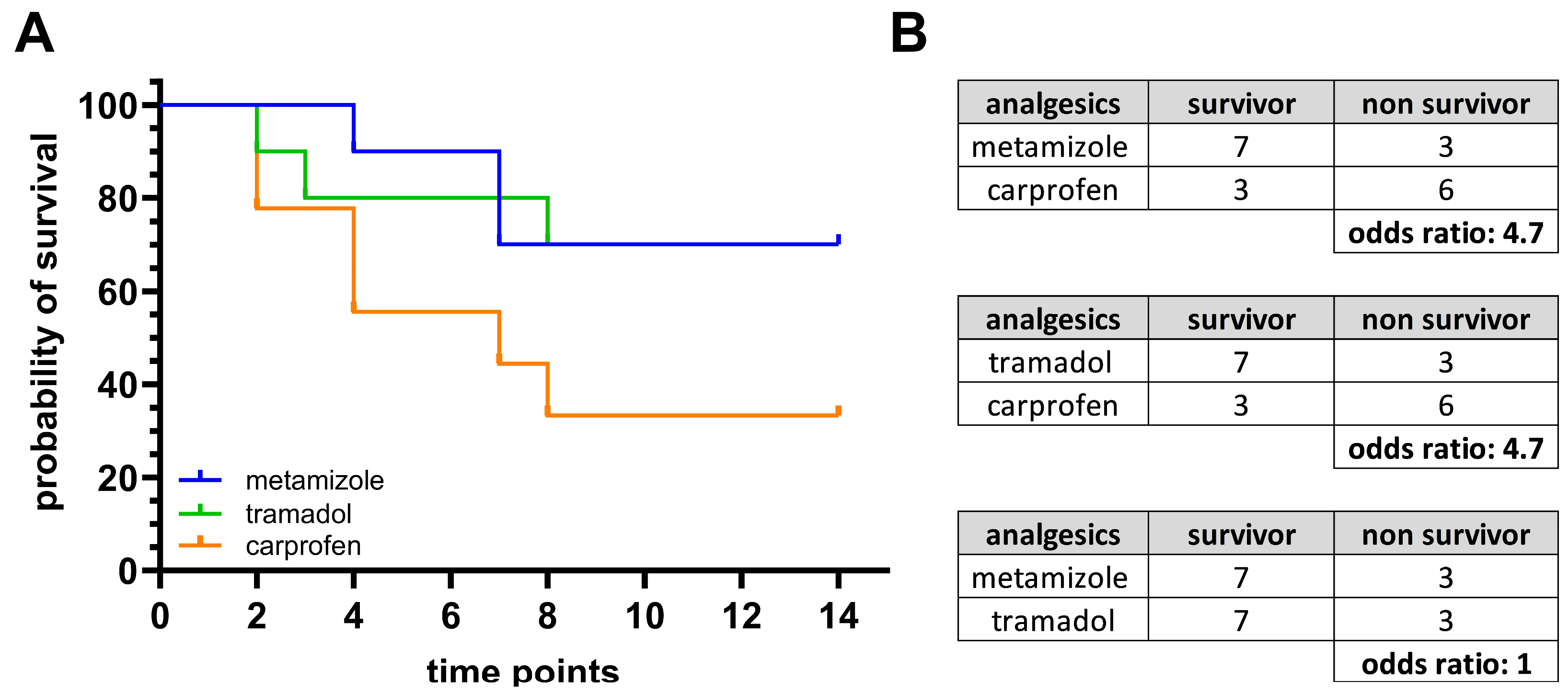

3.2. Metamizole Treatment Is Associated with the Lowest Postoperative Animal Welfare

3.3. Welfare Impairment Persists Despite Analgesic Treatment After BDL

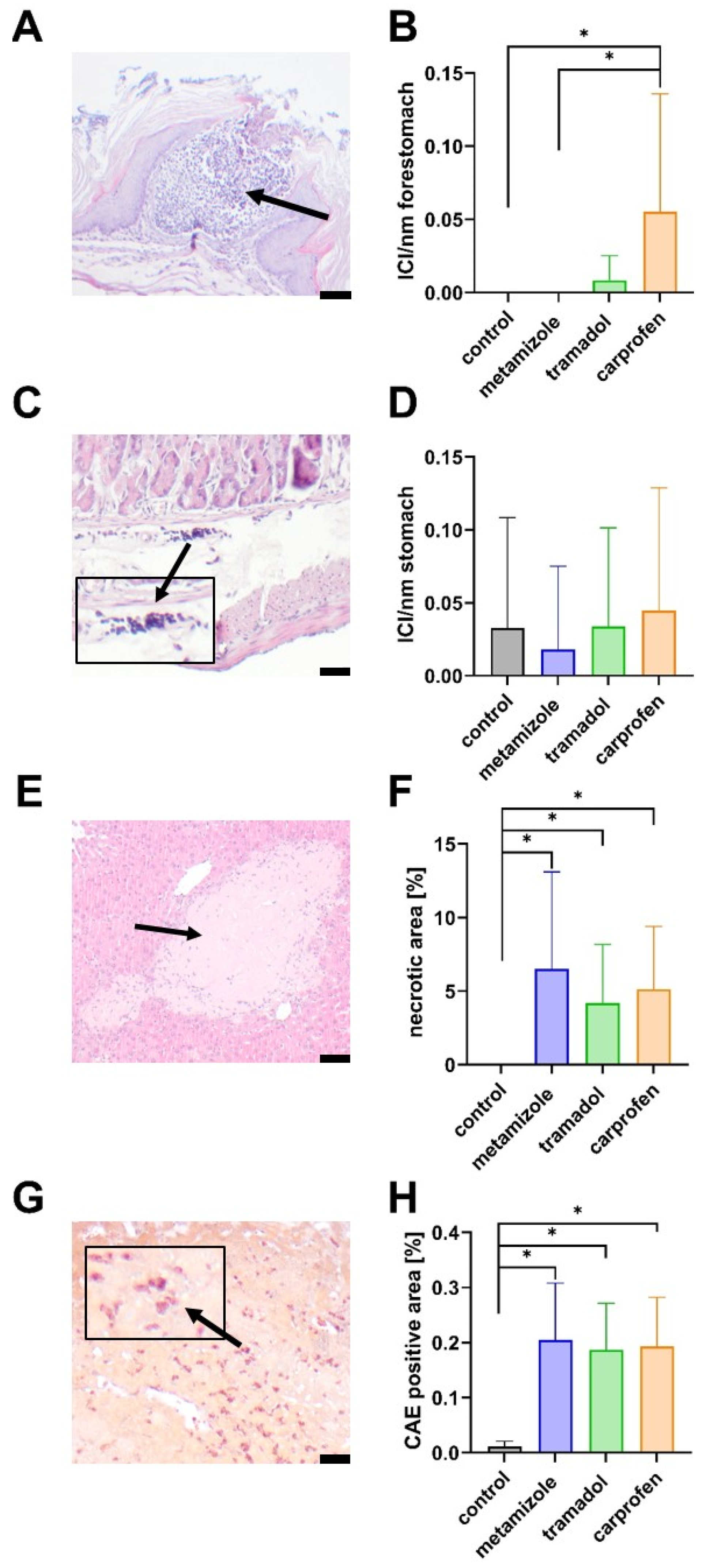

3.4. Histopathological Evaluation of the Stomach and Liver After 14 Days of Cholestasis

4. Discussion

4.1. Sensitivity of Welfare Indicators

4.2. Effects of Analgesics on Healthy Mice

4.3. Recovery After Transmitter Implantation and Analgesics-Specific Effects

4.4. Analgesic Treatment Is Insufficient to Completely Prevent Welfare Impairment in the BDL Model

4.5. Methodological Considerations and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A1 | First measurement after analgesic administration |

| A2 | Last measurement before transmitter implantation |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| BDL | Bile Duct Ligation |

| CAE | 15-naphthol AS-D-chloroacetate esterase |

| COX | cyclooxygenase |

| H&E | Hematoxylin-Eosin |

| HR | Heart rate |

| HRV | Heart rate variability |

| ICI | Immune cell infiltration |

| MGS | Mouse Grimace Scale |

| NSAID | non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PBC | primary biliary cholangitis |

| pre | baseline measurement before analgesic administration |

| PSC | primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| RMSSD | Root mean square of successive differences between normal heartbeats |

| SDNN | Standard deviation of normal-to-normal Intervals |

| TI | transmitter implantation |

References

- Mukherjee, P.; Roy, S.; Ghosh, D.; Nandi, S.K. Role of animal models in biomedical research: A review. Lab. Anim. Res. 2022, 38, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Oliva, A.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Verduzco-Mendoza, A.; Mota-Rojas, D. The Importance of Animal Models in Biomedical Research: Current Insights and Applications. Animals 2023, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petetta, F.; Ciccocioppo, R. Public perception of laboratory animal testing: Historical, philosophical, and ethical view. Addict. Biol. 2021, 26, e12991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterton, M.; Renberg, T.; Kälvemark Sporrong, S. Patients’ attitudes towards animal testing: “To conduct research on animals is, I suppose, a necessary evil”. BioSocieties 2014, 9, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes: 2010/63/EU, 2010. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/63/oj/eng (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique, Special ed.; [Nachdr. der Ausg.] London 1959; Universities Federation for Animal Welfare: Potters Bar, UK, 1992; ISBN 0-900767-78-2. [Google Scholar]

- Burkholder, T.; Foltz, C.; Karlsson, E.; Linton, C.G.; Smith, J.M. Health Evaluation of Experimental Laboratory Mice. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol. 2012, 2, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, R.M.J. Burrowing in rodents: A sensitive method for detecting behavioral dysfunction. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deacon, R. Assessing burrowing, nest construction, and hoarding in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 59, e2607. [Google Scholar]

- Deacon, R.M.J. Assessing nest building in mice. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 1117–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, S.R.; Biernot, S.; Bleich, A.; van Dijk, R.M.; Ernst, L.; Häger, C.; Helgers, S.O.A.; Koegel, B.; Koska, I.; Kuhla, A.; et al. Defining body-weight reduction as a humane endpoint: A critical appraisal. Lab. Anim. 2020, 54, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochut, M.; Heinonen, T.; Snäkä, T.; Gilbert, C.; Le Roy, D.; Roger, T. Using weight loss to predict outcome and define a humane endpoint in preclinical sepsis studies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, D.B.; Griffiths, P.H. Guidelines on the recognition of pain, distress and discomfort in experimental animals and an hypothesis for assessment. Vet. Rec. 1985, 116, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arras, M.; Rettich, A.; Cinelli, P.; Kasermann, H.P.; Burki, K. Assessment of post-laparotomy pain in laboratory mice by telemetric recording of heart rate and heart rate variability. BMC Vet. Res. 2007, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, P. Assessment of pain in animals. Anim. Behav. 1991, 42, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, D.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Chanda, M.L.; Clarke, S.E.; Drummond, T.E.; Echols, S.; Glick, S.; Ingrao, J.; Klassen-Ross, T.; Lacroix-Fralish, M.L.; et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohlbaum, K.; Bert, B.; Dietze, S.; Palme, R.; Fink, H.; Thöne-Reineke, C. Impact of repeated anesthesia with ketamine and xylazine on the well-being of C57BL/6JRj mice. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defensor, E.B.; Corley, M.J.; Blanchard, R.J.; Blanchard, D.C. Facial expressions of mice in aggressive and fearful contexts. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, J.; Boyer, S.; Westlund, K.; Bengtsson, C.; Nordahl, G.; Törnqvist, E. Decreased levels of discomfort in repeatedly handled mice during experimental procedures, assessed by facial expressions. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1109886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappe-Theodor, A.; King, T.; Morgan, M.M. Pros and Cons of Clinically Relevant Methods to Assess Pain in Rodents. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 100, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andermann, M.L.; Lowell, B.B. Toward a Wiring Diagram Understanding of Appetite Control. Neuron 2017, 95, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Austin, J. Pain and Laboratory Animals: Publication Practices for Better Data Reproducibility and Better Animal Welfare. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, N.C.; Nunamaker, E.A.; Turner, P.V. To Treat or Not to Treat: The Effects of Pain on Experimental Parameters. Comp. Med. 2017, 67, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jirkof, P. Side effects of pain and analgesia in animal experimentation. Lab. Anim. 2017, 46, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirkof, P.; Potschka, H. Effects of Untreated Pain, Anesthesia, and Analgesia in Animal Experimentation. In Experimental Design and Reproducibility in Preclinical Animal Studies; Sánchez Morgado, J.M., Brønstad, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 105–126. ISBN 978-3-030-66146-5. [Google Scholar]

- Du Preez, A.; Law, T.; Onorato, D.; Lim, Y.M.; Eiben, P.; Musaelyan, K.; Egeland, M.; Hye, A.; Zunszain, P.A.; Thuret, S.; et al. The type of stress matters: Repeated injection and permanent social isolation stress in male mice have a differential effect on anxiety- and depressive-like behaviours, and associated biological alterations. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Nierath, W.-F.; Leitner, E.; Xie, W.; Revskij, D.; Seume, N.; Zhang, X.; Ehlers, L.; Vollmar, B.; Zechner, D. Comparing animal well-being between bile duct ligation models. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalinger, M.; Schwarzfischer, M.; Niechcial, A.; Atrott, K.; Laimbacher, A.; Jirkof, P.; Scharl, M. Evaluation of the effect of tramadol, paracetamol and metamizole on the severity of experimental colitis. Lab. Anim. 2023, 57, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, T.H.; Bowden, R.S.; Woodward, A.P.; Pang, D.S.J.; Hampton, J.O. Uncontrolled pain: A call for better study design. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1328098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, T.; Lange, S.; Talbot, S.R.; Brandstetter, J.; Leitner, E.; Junghanss, C.; Vollmar, B.; Palme, R.; Richter, A.; Kumstel, S. Improving pain management for murine orthotopic xenograft models of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Lab. Anim. 2025, 54, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gijbels, E.; Pieters, A.; de Muynck, K.; Vinken, M.; Devisscher, L. Rodent models of cholestatic liver disease: A practical guide for translational research. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 656–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frissen, M.; Liao, L.; Schneider, K.M.; Djudjaj, S.; Haybaeck, J.; Wree, A.; Rolle-Kampczyk, U.; von Bergen, M.; Latz, E.; Boor, P.; et al. Bidirectional Role of NLRP3 During Acute and Chronic Cholestatic Liver Injury. Hepatology 2021, 73, 1836–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frezza, E.E.; Gerunda, G.E.; Plebani, M.; Galligioni, A.; Giacomini, A.; Neri, D.; Faccioli, A.M.; Tiribelli, C. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid administration on bile duct proliferation and cholestasis in bile duct ligated rat. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1993, 38, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikata, F.; Sakaue, T.; Nakashiro, K.; Okazaki, M.; Kurata, M.; Okamura, T.; Okura, M.; Ryugo, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Yasugi, T.; et al. Pathophysiology of lung injury induced by common bile duct ligation in mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hong, J.-Y.; Rockwell, C.E.; Copple, B.L.; Jaeschke, H.; Klaassen, C.D. Effect of bile duct ligation on bile acid composition in mouse serum and liver. Liver Int. 2012, 32, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, K.; Flecknell, P. Retrospective review of anesthetic and analgesic regimens used in animal research proposals. Altex 2019, 36, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, S.G.; Otterness, I.G.; Stitt, J.T. A study of the mechanism of action of the mild analgesic dipyrone. Agents Actions 1994, 41, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dizner-Golab, A.; Kosson, D.; Lisowska, B. Metamizole (dipyrone) for multimodal analgesia in postoperative pain in adults. Palliat. Med. Pract. 2025, 19, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; de Gregorio, R.; García-Nieto, R.; Gago, F.; Ortiz, P.; Alemany, S. Regulation of cyclooxygenase activity by metamizol. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 378, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, S.C.; Schmidt, R.; Brenneis, C.; Michaelis, M.; Geisslinger, G.; Scholich, K. Inhibition of cyclooxygenases by dipyrone. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 151, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; de Azevedo, W.F. Computational Analysis of Dipyrone Metabolite 4-Aminoantipyrine As A Cannabinoid Receptor 1 Agonist. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 4741–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, F.; Bantel, C.; Jobski, K. Agranulocytosis attributed to metamizole: An analysis of spontaneous reports in EudraVigilance 1985–2017. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 126, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloms-Funke, P.; Dremencov, E.; Cremers, T.I.F.H.; Tzschentke, T.M. Tramadol increases extracellular levels of serotonin and noradrenaline as measured by in vivo microdialysis in the ventral hippocampus of freely-moving rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 490, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, S.; Minami, M.; Ishihara, K.; Uhl, G.R.; Sora, I.; Ikeda, K. Mu opioid receptor-dependent and independent components in effects of tramadol. Neuropharmacology 2006, 51, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.J.; Perry, C.M. Tramadol: A review of its use in perioperative pain. Drugs 2000, 60, 139–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, C.H.; Bettiga, A. The analgesic tramadol has minimal effect on gastrointestinal motor function. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1997, 43, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, P.C.; Patkar, A.D.; Boswell, K.A.; Benson, C.J.; Schein, J.R. Adverse event profile of tramadol in recent clinical studies of chronic osteoarthritis pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2010, 26, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentnall, C.; Cheng, Z.; McKellar, Q.A.; Lees, P. Potency and selectivity of carprofen enantiomers for inhibition of bovine cyclooxygenase in whole blood assays. Res. Vet. Sci. 2012, 93, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, W.M.; Bagby, G.F. Carprofen: A new nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug. Pharmacology, clinical efficacy and adverse effects. Pharmacotherapy 1987, 7, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Hish, G.; Lester, P.A. Comparison of Systemic Extended-release Buprenorphine and Local Extended-release Bupivacaine-Meloxicam as Analgesics for Laparotomy in Mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2023, 62, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, J.M.; Maher, J.J. Bile duct ligation in rats induces biliary expression of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Le, H.D.; Meisel, J.; Strijbosch, R.A.M.; Nose, V.; Puder, M. Reduction of hepatocellular injury after common bile duct ligation using omega-3 fatty acids. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2008, 43, 2010–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muley, M.M.; Krustev, E.; McDougall, J.J. Preclinical Assessment of Inflammatory Pain. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016, 22, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, O.; Baerwald, C. Wechselwirkungen von Schmerz und chronischer Entzündung. Z. Rheumatol. 2021, 80, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.K.; Finn, D.P. Stress-induced analgesia. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009, 88, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi-Allegra, S.; Cabib, S.; Oliverio, A. Chronic stress reduces the analgesic but not the stimulant effect of morphine in mice. Brain Res. 1986, 380, 357–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierschutzgesetz: TierSchG, 2006. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/tierschg/BJNR012770972.html (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Bachmanov, A.A.; Tordoff, M.G.; Beauchamp, G.K. Ethanol consumption and taste preferences in C57BL/6ByJ and 129/J mice. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1996, 20, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Nierath, W.-F.; Palme, R.; Vollmar, B.; Zechner, D. Analysis of Animal Well-Being When Supplementing Drinking Water with Tramadol or Metamizole during Chronic Pancreatitis. Animals 2020, 10, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, B.; Leitner, E.; Schreiber, T.; Lindner, T.; Schwarz, R.; Aboutara, N.; Ma, Y.; Murua Escobar, H.; Palme, R.; Hinz, B.; et al. Sex Matters-Insights from Testing Drug Efficacy in an Animal Model of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arras, M.; Becker, K.; Bergadano, A. Pain Management for Laboratory Animals: Expert Information from the GV-SOLAS Committee for Anaesthesia in 2021. Available online: https://www.gv-solas.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Pain-Management-for-laboratory-animals_2021.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Kumstel, S.; Vasudevan, P.; Palme, R.; Zhang, X.; Wendt, E.H.U.; David, R.; Vollmar, B.; Zechner, D. Benefits of non-invasive methods compared to telemetry for distress analysis in a murine model of pancreatic cancer. J. Adv. Res. 2020, 21, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stumpf, F.; Algül, H.; Thoeringer, C.K.; Schmid, R.M.; Wolf, E.; Schneider, M.R.; Dahlhoff, M. Metamizol Relieves Pain Without Interfering with Cerulein-Induced Acute Pancreatitis in Mice. Pancreas 2016, 45, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosburg, J.E.; Radanova, L.; Di Marzo, V.; Imming, P.; Lichtman, A.H. Evaluation of the endogenous cannabinoid system in mediating the behavioral effects of dipyrone (metamizol) in mice. Behav. Pharmacol. 2012, 23, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.; Mellström, B.; Fernaud, I.; Naranjo, J.R. Metamizol potentiates morphine effects on visceral pain and evoked c-Fos immunoreactivity in spinal cord. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 351, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, M.; Benkó, R.; Bölcskei, K.; Szolcsányi, J.; Barthó, L.; Pethő, G. Effects of reference analgesics and psychoactive drugs on the noxious heat threshold of mice measured by an increasing-temperature water bath. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 113, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sacerdote, P.; Bianchi, M.; Manfredi, B.; Panerai, A.E. Effects of tramadol on immune responses and nociceptive thresholds in mice. Pain 1997, 72, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumiya, L.C.; Sorge, R.E.; Sotocinal, S.G.; Tabaka, J.M.; Wieskopf, J.S.; Zaloum, A.; King, O.D.; Mogil, J.S. Using the Mouse Grimace Scale to reevaluate the efficacy of postoperative analgesics in laboratory mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2012, 51, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mouedden, M.E.; Meert, T.F. Pharmacological evaluation of opioid and non-opioid analgesics in a murine bone cancer model of pain. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007, 86, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, A.M.; Kennedy, L.H.; Na, J.J.; Nemzek-Hamlin, J.A. Efficacy of Tramadol as a Sole Analgesic for Postoperative Pain in Male and Female Mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2015, 54, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Jirkof, P.; Cesarovic, N.; Rettich, A.; Nicholls, F.; Seifert, B.; Arras, M. Burrowing behavior as an indicator of post-laparotomy pain in mice. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjendal, K.; Ottesen, J.L.; Olsson, I.A.S.; Sørensen, D.B. Burrowing and nest building activity in mice after exposure to grid floor, isoflurane or ip injections. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 206, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.E.; Park, D.; Song, K.-I.; Seong, J.-K.; Chung, S.; Youn, I. Differential heart rate variability and physiological responses associated with accumulated short- and long-term stress in rodents. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 171, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisiyiti, A.; Tian, M.; Chen, J.D.Z. Acceleration of postoperative recovery with brief intraoperative vagal nerve stimulation mediated via the autonomic mechanism. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1188781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, P.L.; Everse, L.A.; Bernsen, M.R.; Baumans, V.; Hellebrekers, L.J.; Kruitwagen, C.L.; den Otter, W. Analgesics in mice used in cancer research: Reduction of discomfort? Lab. Anim. 1997, 31, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, M.; Graf, T.R.; Graf, R.; Kron, M.; Arras, M.; Zechner, D.; Palme, R.; Talbot, S.R.; Jirkof, P. Analysis of Pain and Analgesia Protocols in Acute Cerulein-Induced Pancreatitis in Male C57BL/6 Mice. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 744638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.A.; Doods, H.; Lamla, T.; Pekcec, A. Pharmacological characterization of intraplantar Complete Freund’s Adjuvant-induced burrowing deficits. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 301, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.Z.; Kissling, G.E.; Hoenerhoff, M.J.; King-Herbert, A.P.; Blankenship-Paris, T. Evaluation of dosages and routes of administration of tramadol analgesia in rats using hot-plate and tail-flick tests. Lab. Anim. 2010, 39, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Déciga-Campos, M.; Ramírez-Marín, P.M.; López-Muñoz, F.J. Synergistic antinociceptive interaction between palmitoylethanolamide and tramadol in the mouse formalin test. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 765, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helwig, B.G.; Ward, J.A.; Blaha, M.D.; Leon, L.R. Effect of intraperitoneal radiotelemetry instrumentation on voluntary wheel running and surgical recovery in mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2012, 51, 600–608. [Google Scholar]

- Cesarovic, N.; Jirkof, P.; Rettich, A.; Arras, M. Implantation of radiotelemetry transmitters yielding data on ECG, heart rate, core body temperature and activity in free-moving laboratory mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2011, 57, e3260. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and the Cardiovascular System. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2025, 45, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-H. Renal effects of prostaglandins and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2008, 6, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, C.E.; Breyer, R.M. Prostaglandin E2 modulation of blood pressure homeostasis: Studies in rodent models. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2011, 96, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höcherl, K.; Endemann, D.; Kammerl, M.C.; Grobecker, H.F.; Kurtz, A. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibition increases blood pressure in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 136, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.B. Cardiovascular effects of the cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Hypertension 2007, 49, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krum, H.; Aw, T.-J.; Liew, D.; Haas, S. Blood pressure effects of COX-2 inhibitors. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2006, 47 (Suppl. S1), S43–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bootsma, M.; Swenne, C.A.; van Bolhuis, H.H.; Chang, P.C.; Cats, V.M.; Bruschke, A.V. Heart rate and heart rate variability as indexes of sympathovagal balance. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 266, H1565-71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, F.; García-Saisó, S.; Lemini, C.; Ramírez-Solares, R.; Vidrio, H.; Mendoza-Fernández, V. Metamizol acts as an ATP sensitive potassium channel opener to inhibit the contracting response induced by angiotensin II but not to norepinephrine in rat thoracic aorta smooth muscle. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2005, 43, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegre Cannon, C.; Kissling, G.E.; Goulding, D.R.; King-Herbert, A.P.; Blankenship-Paris, T. Analgesic effects of tramadol, carprofen or multimodal analgesia in rats undergoing ventral laparotomy. Lab. Anim. 2011, 40, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C.; Bentley, E.; Hetzel, S.; Smith, L.J. Comparison of carprofen and tramadol for postoperative analgesia in dogs undergoing enucleation. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 245, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, S.R.; Struve, B.; Wassermann, L.; Heider, M.; Weegh, N.; Knape, T.; Hofmann, M.C.J.; von Knethen, A.; Jirkof, P.; Keubler, L.; et al. One score to rule them all: Severity assessment in laboratory mice. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Tanaka, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Yokota, A. COX inhibition and NSAID-induced gastric damage--roles in various pathogenic events. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005, 5, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.L.; McKnight, W.; Reuter, B.K.; Vergnolle, N. NSAID-induced gastric damage in rats: Requirement for inhibition of both cyclooxygenase 1 and 2. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio, F.; Seawall, S.; Pocelinko, R.; DeBarbieri, B.; Benz, W.; Berger, L.; Morgan, L.; Pao, J.; Williams, T.H.; Koechlin, B. Metabolism of carprofen, a nonsteroid anti-inflammatory agent, in rats, dogs, and humans. J. Pharm. Sci. 1980, 69, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, H.; Xiong, L.; Ni, Y.; Busch, A.; Bauer, M.; Press, A.T.; Panagiotou, G. Impaired flux of bile acids from the liver to the gut reveals microbiome-immune interactions associated with liver damage. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Ran, X.; Gu, Z.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Wen, L.; Ji, G.; Wang, R. Bile acid-gut microbiota imbalance in cholestasis and its long-term effect in mice. mSystems 2024, 9, e0012724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumaswala, R.; Berkowitz, D.; Heubi, J.E. Adaptive response of the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids to extrahepatic cholestasis. Hepatology 1996, 23, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, B.A.; Weaver, H.L.; Kim, J.; Bowman, M.W.; Knych, H.K.; Kendall, L.V. A Pharmacokinetic and Analgesic Efficacy Study of Carprofen in Female CD1 Mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2023, 62, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasenapp, A.; Bankstahl, J.P.; Bähre, H.; Glage, S.; Bankstahl, M. Subcutaneous and orally self-administered high-dose carprofen shows favorable pharmacokinetic and tolerability profiles in male and female C57BL/6J mice. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1430726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Déciga-Campos, M.; López, U.G.; Reval, M.I.D.; López-Muñoz, F.J. Enhancement of antinociception by co-administration of an opioid drug (morphine) and a preferential cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor (rofecoxib) in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 460, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroin, J.S.; Buvanendran, A.; McCarthy, R.J.; Hemmati, H.; Tuman, K.J. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition potentiates morphine antinociception at the spinal level in a postoperative pain model. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2002, 27, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.C. A Review of Strain and Sex Differences in Response to Pain and Analgesia in Mice. Comp. Med. 2019, 69, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.G.; Bryant, C.D.; Lariviere, W.R.; Olsen, M.S.; Giles, B.E.; Chesler, E.J.; Mogil, J.S. The heritability of antinociception II: Pharmacogenetic mediation of three over-the-counter analgesics in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 305, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, J.D.; Craft, R.M.; LeResche, L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Berkley, K.J.; Fillingim, R.B.; Gold, M.S.; Holdcroft, A.; Lautenbacher, S.; Mayer, E.A.; et al. Studying sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia: A consensus report. Pain 2007, 132 (Suppl. S1), S26–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, R.K.; Woo, Y.C.; Park, S.S.; Brennan, T.J. Strain and sex influence on pain sensitivity after plantar incision in the mouse. Anesthesiology 2006, 105, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craft, R.M.; Mogil, J.S.; Aloisi, A.M. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: The role of gonadal hormones. Eur. J. Pain 2004, 8, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kest, B.; Wilson, S.G.; Mogil, J.S. Sex Differences in Supraspinal Morphine Analgesia Are Dependent on Genotype. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 289, 1370–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leitner, E.; Schreiber, T.; Krug, H.; Vasudevan, P.; Kumstel, S.; Ernst, L.; Tolba, R.H.; Vollmar, B.; Zechner, D. Comparative Evaluation of Analgesics in a Murine Bile Duct Ligation Model. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3034. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123034

Leitner E, Schreiber T, Krug H, Vasudevan P, Kumstel S, Ernst L, Tolba RH, Vollmar B, Zechner D. Comparative Evaluation of Analgesics in a Murine Bile Duct Ligation Model. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3034. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123034

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeitner, Emily, Tim Schreiber, Hanna Krug, Praveen Vasudevan, Simone Kumstel, Lisa Ernst, René Hany Tolba, Brigitte Vollmar, and Dietmar Zechner. 2025. "Comparative Evaluation of Analgesics in a Murine Bile Duct Ligation Model" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3034. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123034

APA StyleLeitner, E., Schreiber, T., Krug, H., Vasudevan, P., Kumstel, S., Ernst, L., Tolba, R. H., Vollmar, B., & Zechner, D. (2025). Comparative Evaluation of Analgesics in a Murine Bile Duct Ligation Model. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3034. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123034