Biological Plausibility Between Long-COVID and Periodontal Disease Development or Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology of the Literature Search

3. LC Reported Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations

4. LC Clinical Manifestations in the Oral Cavity

5. Periodontitis: Definition and Systemic Impact

6. Epidemiologic Factors Shared Between LC and Periodontitis

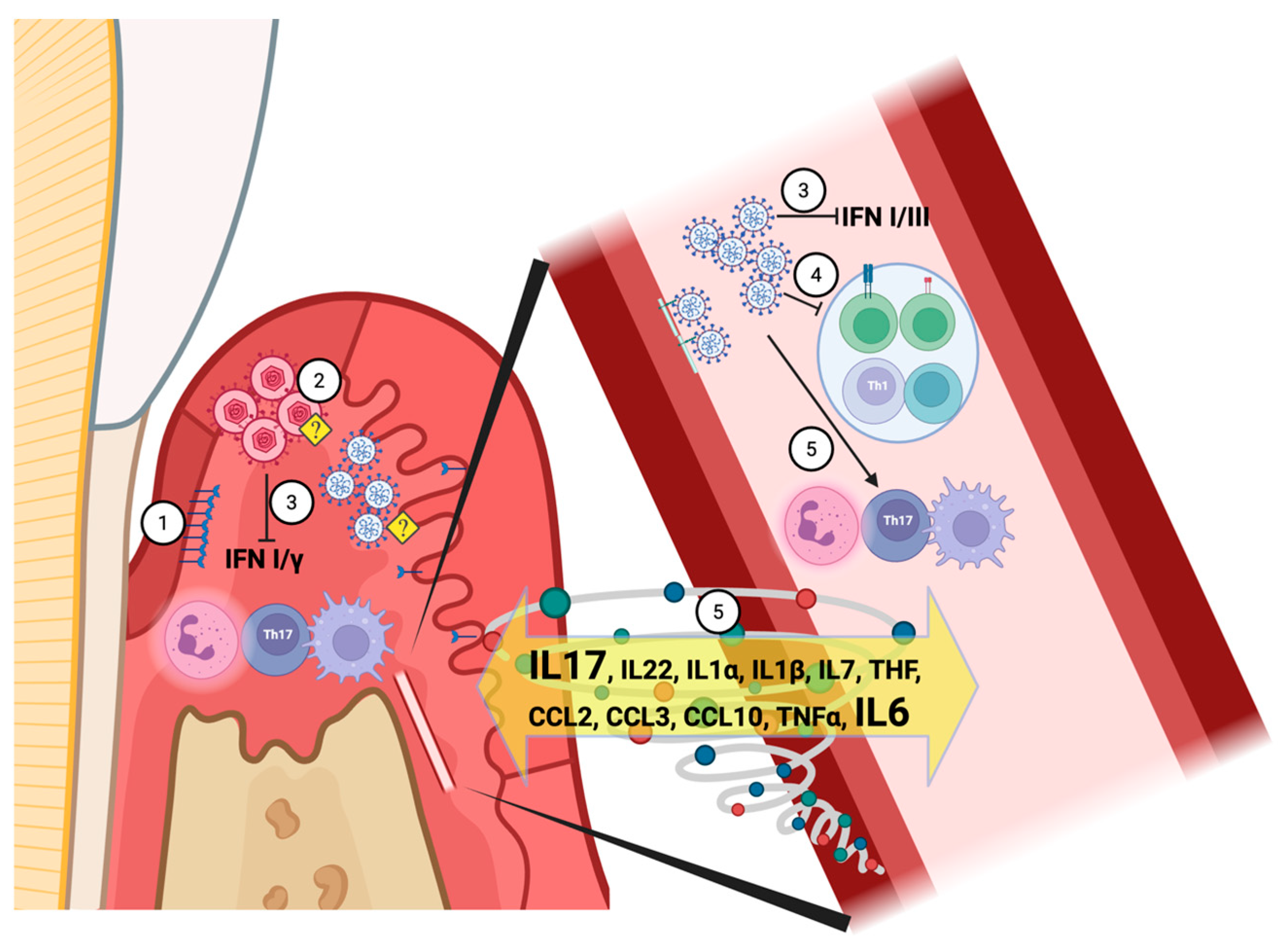

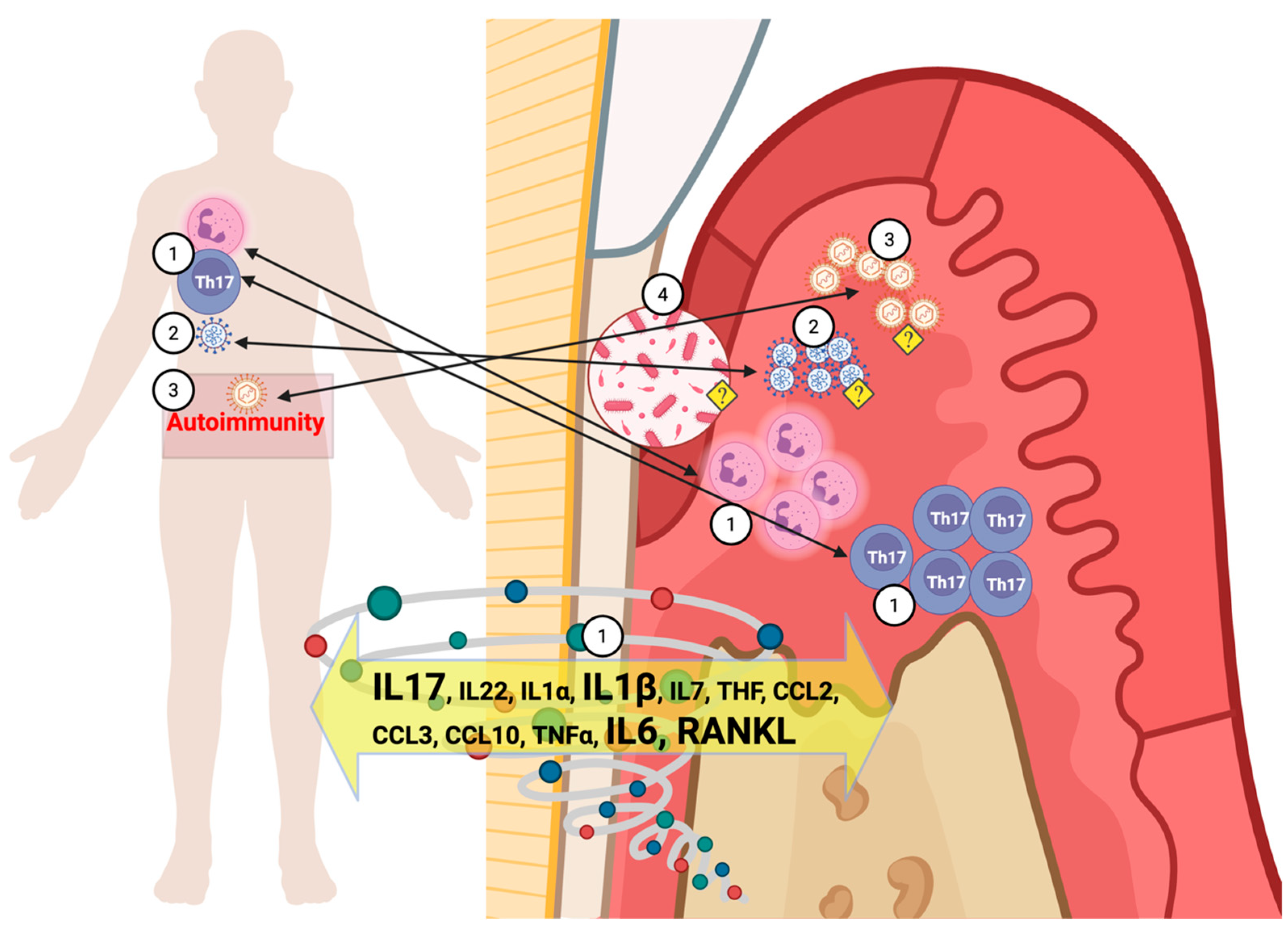

7. Immuno-Pathophysiology Mechanisms Shared by LC and Periodontitis

7.1. Early Immune Response to the SARS-CoV-2

7.1.1. Interferon-Mediated Local Innate Immune Response to a Viral Infection

7.1.2. The Short-Term T-Cell Response to SARS-CoV-2

7.1.3. Neutrophils and the “Cytokine Storm”

7.1.4. Monocytes and Macrophages

7.2. A Persistent Active Immune Response to the SARS-CoV-2, the Key to LC

7.2.1. The Resolution of the SARS-CoV-2 Infection

7.2.2. A Persistent Dysregulation of T Cells in LC

7.2.3. A Broad and Continuous Adaptive Immune Response Is Part of LC

7.3. The Complement System

8. LC Inflammation at the Tissue Level

8.1. The Role of IL-17, RANKL, and Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) in Bone Metabolism Related to LC

8.2. The Role of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) on the LC and Periodontitis Association

9. The Microbiologic Impact of LC

9.1. The Reactivation of Viral Infections as a Result of LC Immune Response

9.2. LC May Affect Oral Dysbiosis, Increasing Susceptibility to Chronic Infections, Including Periodontitis

10. The Potential Mechanisms of COVID-19/LC: Effects on Periodontitis

11. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2020. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull-Otterson, L.; Baca, S.; Saydah, S.; Boehmer, T.K.; Adjei, S.; Gray, S.; Harris, A.M. Post–COVID Conditions Among Adult COVID-19 Survivors Aged 18–64 and ≥65 Years—United States, March 2020–November 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladds, E.; Rushforth, A.; Wieringa, S.; Taylor, S.; Rayner, C.; Husain, L.; Greenhalgh, T. Persistent symptoms after COVID-19: Qualitative study of 114 “long Covid” patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Nirantharakumar, K.; Hughes, S.; Myles, P.; Williams, T.; Gokhale, K.M.; Taverner, T.; Chandan, J.S.; Brown, K.; Simms-Williams, N.; et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A. Long-Haul COVID. Neurology 2020, 95, 559–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaweethai, T.; Jolley, S.E.; Karlson, E.W.; Levitan, E.B.; Levy, B.; McComsey, G.A.; McCorkell, L.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Parthasarathy, S.; Singh, U.; et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA 2023, 329, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowe, B.; Xie, Y.; Al-Aly, Z. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2398–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malizos, K.N. Long COVID-19: A New Challenge to Public Health. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2022, 104, 205–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, V.; Arroliga, A.C.; Bourgeois, J.A.; Boehm, L.M.; McNeal, M.J.; Widmer, A.J.; McNeal, T.M.; Kesler, S.R. Symptom Clusters Seen in Adult COVID-19 Recovery Clinic Care Seekers. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.E.; Assaf, G.S.; McCorkell, L.; Wei, H.; Low, R.J.; Re’EM, Y.; Redfield, S.; Austin, J.P.; Akrami, A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reese, J.T.; Blau, H.; Casiraghi, E.; Bergquist, T.; Loomba, J.J.; Callahan, T.J.; Laraway, B.; Antonescu, C.; Coleman, B.; Gargano, M.; et al. Generalisable long COVID subtypes: Findings from the NIH N3C and RECOVER programmes. EBioMedicine 2023, 87, 104413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet 2023, 401, e21–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, A.; Cuthbertson, D.J.; Wootton, D.; Crooks, M.; Gabbay, M.; Eichert, N.; Mouchti, S.; Pansini, M.; Roca-Fernandez, A.; Thomaides-Brears, H.; et al. Multi-organ impairment and long COVID: A 1-year prospective, longitudinal cohort study. J. R. Soc. Med. 2023, 116, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlis, R.H.; Trujillo, K.L.; Safarpour, A.; Santillana, M.; Ognyanova, K.; Druckman, J.; Lazer, D. Research Letter: Association between long COVID symptoms and employment status. medRxiv 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admon, A.J.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Kamphuis, L.A.; Gundel, S.J.; Sahetya, S.K.; Peltan, I.D.; Chang, S.Y.; Han, J.H.; Vranas, K.C.; Mayer, K.P.; et al. Assessment of Symptom, Disability, and Financial Trajectories in Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19 at 6 Months. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2255795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.M. The Costs of Long COVID. JAMA Health Forum 2022, 3, e221809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAIR Health. A Detailed Study of Patients with Long-Haul COVID: An analysis of Private Healthcare Claims; FAIR Health, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gandjour, A. Long COVID: Costs for the German economy and health care and pension system. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premraj, L.; Kannapadi, N.V.; Briggs, J.; Seal, S.M.; Battaglini, D.; Fanning, J.; Suen, J.; Robba, C.; Fraser, J.; Cho, S.-M. Mid and long-term neurological and neuropsychiatric manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome: A meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 434, 120162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.M.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M.; Topol, E.J. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, P.; Qiao, F.; Chen, Y.; Chan, D.Y.L.; Yim, H.C.H.; Fok, K.L.; Chen, H. SARS-CoV-2 and male infertility: From short- to long-term impacts. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2023, 46, 1491–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, H.; Chaftari, A.-M.; Subbiah, I.M.; E Malek, A.; Jiang, Y.; Lamie, P.; Granwehr, B.; John, T.; Yepez, E.; Borjan, J.; et al. Long COVID in cancer patients: Preponderance of symptoms in majority of patients over long time period. eLife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Dong, J.; Guo, Q.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L.; Ren, B. The Oral Complications of COVID-19. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 803785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.; Abou-Bakr, A.; Hussein, R.R.; El-Gawish, A.A.; Ras, A.E.; Ghalwash, D.M. Oral mucormycosis in post-COVID-19 patients: A case series. Oral. Dis. 2022, 28, 2591–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafałowicz, B.; Wagner, L.; Rafałowicz, J. Long COVID Oral Cavity Symptoms Based on Selected Clinical Cases. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandwani, N.; Dabhekar, S.; Selvi, K.; Mohamed, R.N.; Abullais, S.S.; Moothedath, M.; Jadhav, G.; Chandwani, J.; Karobari, M.I.; Pawar, A.M. Oral Tissue Involvement and Probable Factors in Post-COVID-19 Mucormycosis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaifi, A.; Sultan, A.S.; Montelongo-Jauregui, D.; Meiller, T.F.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A. Long-Term Post-COVID-19 Associated Oral Inflammatory Sequelae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 831744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, W.; Kamal, M.M.; Rafique, Z.; Rahat, M.; Mumtaz, H. Case of maxillary actinomycotic osteomyelitis, a rare post COVID complication-case report. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 80, 104242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alramadhan, S.A.; Sam, S.S.; Young, S.; Cohen, D.M.; Islam, M.N.; Bhattacharyya, I. COVID-related mucormycosis mimicking dental infection. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Cases 2023, 9, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jumaily, H.A.; Al-Anee, A.M.; Al-Quisi, A.F. Atypical clinical features of post COVID-19 mucormycosis: A case series. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2023, 9, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frencken, J.E.; Sharma, P.; Stenhouse, L.; Green, D.; Laverty, D.; Dietrich, T. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis—A comprehensive review. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, S94–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarin, M.; Silva, F.H.; Pontes, A.F.L.; Lima, B.D.; Pirih, F.Q.; Muniz, F.W.M.G. Association between sequelae of COVID-19 with periodontal disease and obesity: A cross-sectional study. J. Periodontol. 2023, 95, 688–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Mealey, B.L.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Bartold, P.M.; Dommisch, H.; Eickholz, P.; Geisinger, M.L.; Genco, R.J.; Glogauer, M.; Goldstein, M.; et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S74–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, P.I.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Genco, R.J. Recent epidemiologic trends in periodontitis in the USA. Periodontology 2000 2020, 82, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Bernabe, E.; Dahiya, M.; Bhandari, B.; Murray, C.J.; Marcenes, W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: A systematic review and meta-regression. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapanou, P.N. Epidemiology of periodontal diseases: An update. J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 1999, 1, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Friedewald, V.E.; Kornman, K.S.; Beck, J.D.; Genco, R.; Goldfine, A.; Libby, P.; Offenbacher, S.; Ridker, P.M.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Roberts, W.C. The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology Editors’ Consensus: Periodontitis and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease††Published simultaneously in the Journal of Periodontology, the Official Journal of the American Academy of Periodontology. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009, 104, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.B.D.A.; Peixoto, C.B.; Amino, J.G.d.C.; Cortes, L.; Tura, B.; Nunn, M.; Giambiagi-Demarval, M.; Sansone, C. Coronary atherosclerosis and periodontitis have similarities in their clinical presentation. Front. Oral Health 2024, 4, 1324528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Academy of Periodontology. American Academy of Periodontology Statement on Risk Assessment. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriankaja, O.M.; Joshipura, K.J.; Levine, M.A.; Ramirez-Vick, M.; Rivas-Agosto, J.A.; Duconge, J.S.; Graves, D.T. Hispanic adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus using lipid-lowering agents have better periodontal health than non-users. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriankaja, O.M.; Adatorwovor, R.; Kantarci, A.; Hasturk, H.; Shaddox, L.; Levine, M.A. Periodontal Disease, Local and Systemic Inflammation in Puerto Ricans with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriankaja, O.M.; Pérez, C.M.; Modi, A.; Suaréz, E.L.; Gower, B.A.; Rodríguez, E.; Joshipura, K. Systemic Inflammation, Endothelial Function, and Risk of Periodontitis in Overweight/Obese Adults. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinane, D.F.; Lappin, D.F.; Koulouri, O.; Buckley, A. Humoral immune responses in periodontal disease may have mucosal and systemic immune features. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1999, 115, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappin, D.F.; McGregor, A.M.P.; Kinane, D.F. The systemic immune response is more prominent than the mucosal immune response in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2003, 30, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, E.-C.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Lin, H.-Y.; Tseng, S.-Y.; Hsieh, Y.-T.; Shieh, J.-A.; Huang, Y.-H.; Tsai, H.-T.; Feng, S.-W.; Peng, T.-Y.; et al. Unraveling the Link between Periodontitis and Coronavirus Disease 2019: Exploring Pathogenic Pathways and Clinical Implications. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löe, H. Periodontal Disease: The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1993, 16, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, T.; König, J.; Borgnakke, W.S.; Pink, C.; Meisel, P. Periodontal complications of hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus: Epidemiologic complexity and clinical challenge. Periodontology 2000 2018, 78, 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crook, H.; Raza, S.; Nowell, J.; Young, M.; Edison, P. Long Covid—Mechanisms, Risk Factors, and Management. BMJ 2021, 374, n1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimlich, R. What Is Long COVID? 2023. Available online: https://www.verywellhealth.com/covid-long-haulers-5101640 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Darby, I. Risk factors for periodontitis & peri-implantitis. Periodontology 2000 2022, 90, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, H.M.; Koroukian, S.M.; Stange, K.; Schiltz, N.K.; Bissada, N.F. Identifying Factors Associated with Periodontal Disease Using Machine Learning. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2022, 12, 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Ceriello, A.; Buysschaert, M.; Chapple, I.; Demmer, R.T.; Graziani, F.; Herrera, D.; Jepsen, S.; Lione, L.; Madianos, P.; et al. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: Consensus report and guidelines of the joint workshop on periodontal diseases and diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizales-Sepúlveda, E.F.; Ordaz-Farías, A.; Vera-Pineda, R.; Flores-Ramírez, R. Periodontal Disease, Systemic Inflammation and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Hear. Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Shawish, G.; Betsy, J.; Anil, S. Is Obesity a Risk Factor for Periodontal Disease in Adults? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Agosto, J.A.; Camacho-Monclova, D.M.; Vergara, J.L.; Vivaldi-Oliver, J.; Andriankaja, O.M. Disparities in periodontal diseases occurrence among Hispanic population with Type 2 Diabetes: The LLIPDS Study. EC Dent. Sci. 2021, 20, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.; Thomas, D.T.; Vázquez-Morales, G.N.; Puckett, L.; Rodriguez, M.D.M.; Stromberg, A.; Shaddox, L.M.; Santamaria, M.P.; Pearce, K.; Andriankaja, O.M.; et al. Cross-sectional association among dietary habits, periodontitis, and uncontrolled diabetes in Hispanics: The LLIPDS study. Front. Oral Health 2025, 6, 1468995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.; Weaver, C. Janeway’s immunobiology. In Garland Science; WW Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sette, A.; Crotty, S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell 2021, 184, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Zhu, Y.; Mao, J.; Du, R. T cell immunobiology and cytokine storm of COVID-19. Scand. J. Immunol. 2021, 93, e12989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galani, I.-E.; Rovina, N.; Lampropoulou, V.; Triantafyllia, V.; Manioudaki, M.; Pavlos, E.; Koukaki, E.; Fragkou, P.C.; Panou, V.; Rapti, V.; et al. Untuned antiviral immunity in COVID-19 revealed by temporal type I/III interferon patterns and flu comparison. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunachalam, P.S.; Wimmers, F.; Mok, C.K.P.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Scott, M.; Hagan, T.; Sigal, N.; Feng, Y.; Bristow, L.; Tsang, O.T.-Y.; et al. Systems biological assessment of immunity to mild versus severe COVID-19 infection in humans. Science 2020, 369, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Melo, D.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Liu, W.-C.; Uhl, S.; Hoagland, D.; Møller, R.; Jordan, T.X.; Oishi, K.; Panis, M.; Sachs, D.; et al. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell 2020, 181, 1036–1045.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjadj, J.; Yatim, N.; Barnabei, L.; Corneau, A.; Boussier, J.; Smith, N.; Péré, H.; Charbit, B.; Bondet, V.; Chenevier-Gobeaux, C.; et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science 2020, 369, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Gómez, A.; Vitallé, J.; Gasca-Capote, C.; Gutierrez-Valencia, A.; Trujillo-Rodriguez, M.; Serna-Gallego, A.; Muñoz-Muela, E.; Jiménez-Leon, M.d.L.R.; Benhnia, M.R.-E.; Rivas-Jeremias, I.; et al. Dendritic cell deficiencies persist seven months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 2128–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Wood, J.; Jaycox, J.R.; Dhodapkar, R.M.; Lu, P.; Gehlhausen, J.R.; Tabachnikova, A.; Greene, K.; Tabacof, L.; Malik, A.A.; et al. Distinguishing features of long COVID identified through immune profiling. Nature 2023, 623, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoni, V.; Sacchi, A.; Cimini, E.; Notari, S.; Grassi, G.; Tartaglia, E.; Casetti, R.; Giancola, M.L.; Bevilacqua, N.; Maeurer, M.; et al. An Inflammatory Profile Correlates With Decreased Frequency of Cytotoxic Cells in Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2272–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, B.; Wang, C.; Tan, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Ning, L.; Chen, L.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; et al. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharawi, H.; Heyman, O.; Mizraji, G.; Horev, Y.; Laviv, A.; Shapira, L.; Yona, S.; Hovav, A.; Wilensky, A. The Prevalence of Gingival Dendritic Cell Subsets in Periodontal Patients. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Feng, P.; Slots, J. Herpesvirus-bacteria synergistic interaction in periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 2020, 82, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammil, D.; Jayanthi, M.; Faizuddin, H.M.; Ahamadi, N. Association of interferon lambda-1 with herpes simplex viruses-1 and -2, Epstein-Barr virus, and human cytomegalovirus in chronic periodontitis. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2017, 8, e12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajita, K.; Honda, T.; Amanuma, R.; Domon, H.; Okui, T.; Ito, H.; Yoshie, H.; Tabeta, K.; Nakajima, T.; Yamazaki, K. Quantitative messenger RNA expression of Toll-like receptors and interferon-alpha1 in gingivitis and periodontitis. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 22, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Dong, S.; Sun, H.; Gao, S.; Zhou, T.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; et al. Immune response pattern across the asymptomatic, symptomatic and convalescent periods of COVID-19. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2022, 1870, 140736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Weiskopf, D.; Ramirez, S.I.; Mateus, J.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Rawlings, S.A.; Sutherland, A.; Premkumar, L.; Jadi, R.S.; et al. Targets of T Cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus in Humans with COVID-19 Disease and Unexposed Individuals. Cell 2020, 181, 1489–1501.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryavtsev, I.; Rubinstein, A.; Golovkin, A.; Kalinina, O.; Vasilyev, K.; Rudenko, L.; Isakova-Sivak, I. Dysregulated Immune Responses in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients: A Comprehensive Overview. Viruses 2022, 14, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.A.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Lima, K.V.B.; Lima, L.N.G.C. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1001198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parackova, Z.; Bloomfield, M.; Klocperk, A.; Sediva, A. Neutrophils mediate Th17 promotion in COVID-19 patients. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2021, 109, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martonik, D.; Parfieniuk-Kowerda, A.; Rogalska, M.; Flisiak, R. The Role of Th17 Response in COVID-19. Cells 2021, 10, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Biasi, S.; Meschiari, M.; Gibellini, L.; Bellinazzi, C.; Borella, R.; Fidanza, L.; Gozzi, L.; Iannone, A.; Tartaro, D.L.; Mattioli, M.; et al. Marked T cell activation, senescence, exhaustion and skewing towards TH17 in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibabaw, T. Inflammatory Cytokine: IL-17A Signaling Pathway in Patients Present with COVID-19 and Current Treatment Strategy. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Ju, D.; Lin, Y.; Chen, W. The role of interleukin-22 in lung health and its therapeutic potential for COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 951107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcorn, J.F. IL-22 Plays a Critical Role in Maintaining Epithelial Integrity During Pulmonary Infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenobia, C.; Hajishengallis, G. Basic biology and role of interleukin-17 in immunity and inflammation. Periodontology 2000 2015, 69, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilich, T.; Nelde, A.; Heitmann, J.S.; Maringer, Y.; Roerden, M.; Bauer, J.; Rieth, J.; Wacker, M.; Peter, A.; Hörber, S.; et al. T cell and antibody kinetics delineate SARS-CoV-2 peptides mediating long-term immune responses in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.W.; Linderman, S.L.; Moodie, Z.; Czartoski, J.; Lai, L.; Mantus, G.; Norwood, C.; Nyhoff, L.E.; Edara, V.V.; Floyd, K.; et al. Longitudinal analysis shows durable and broad immune memory after SARS-CoV-2 infection with persisting antibody responses and memory B and T cells. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Liang, W.; Pang, J.; Xu, G.; Chen, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lai, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Dynamics of TCR repertoire and T cell function in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamayoshi, S.; Yasuhara, A.; Ito, M.; Akasaka, O.; Nakamura, M.; Nakachi, I.; Koga, M.; Mitamura, K.; Yagi, K.; Maeda, K.; et al. Antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 decline, but do not disappear for several months. eClinicalMedicine 2021, 32, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, A.; Muecksch, F.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Wang, Z.; Finkin, S.; Gaebler, C.; Ramos, V.; Cipolla, M.; Mendoza, P.; Agudelo, M.; et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain antibody evolution after mRNA vaccination. Nature 2021, 600, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, E.M.; Arosa, F.A. CD8+ T Cells in Chronic Periodontitis: Roles and Rules. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Woo, K.M.; Ko, S.-H.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, S.-J.; Kim, H.-M.; Kwon, B.S. Osteoclastogenesis is enhanced by activated B cells but suppressed by activated CD8+ T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001, 31, 2179–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Korostoff, J.M. Revisiting the Page & Schroeder model: The good, the bad and the unknowns in the periodontal host response 40 years later. Periodontology 2000 2017, 75, 116–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuri-Cervantes, L.; Pampena, M.B.; Meng, W.; Rosenfeld, A.M.; Ittner, C.A.G.; Weisman, A.R.; Agyekum, R.S.; Mathew, D.; Baxter, A.E.; Vella, L.A.; et al. Comprehensive mapping of immune perturbations associated with severe COVID-19. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabd7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meizlish, M.L.; Pine, A.B.; Bishai, J.D.; Goshua, G.; Nadelmann, E.R.; Simonov, M.; Chang, C.-H.; Zhang, H.; Shallow, M.; Bahel, P.; et al. A neutrophil activation signature predicts critical illness and mortality in COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 1164–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderbeke, L.; Van Mol, P.; Van Herck, Y.; De Smet, F.; Humblet-Baron, S.; Martinod, K.; Antoranz, A.; Arijs, I.; Boeckx, B.; Bosisio, F.M.; et al. Monocyte-driven atypical cytokine storm and aberrant neutrophil activation as key mediators of COVID-19 disease severity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.; Leunig, A.; Pekayvaz, K.; Popp, O.; Joppich, M.; Polewka, V.; Escaig, R.; Anjum, A.; Hoffknecht, M.-L.; Gold, C.; et al. Self-sustaining IL-8 loops drive a prothrombotic neutrophil phenotype in severe COVID-19. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e150862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frishberg, A.; Kooistra, E.; Nuesch-Germano, M.; Pecht, T.; Milman, N.; Reusch, N.; Warnat-Herresthal, S.; Bruse, N.; Händler, K.; Theis, H.; et al. Mature neutrophils and a NF-κB-to-IFN transition determine the unifying disease recovery dynamics in COVID-19. Cell Rep. Med. 2022, 3, 100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sanborn, M.A.; Dai, Y.; Rehman, J. Temporal transcriptomic analysis using TrendCatcher identifies early and persistent neutrophil activation in severe COVID-19. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 7, e157255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukema, B.N.; Smit, K.; Hopman, M.T.E.; Bongers, C.C.W.G.; Pelgrim, T.C.; Rijk, M.H.; Platteel, T.N.; Venekamp, R.P.; Zwart, D.L.M.; Rutten, F.H.; et al. Neutrophil and Eosinophil Responses Remain Abnormal for Several Months in Primary Care Patients With COVID-19 Disease. Front. Allergy 2022, 3, 942699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, N.; Kesting, M. Cytokines in gingivitis and periodontitis: From pathogenesis to therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1435054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Q. The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorch, S.K.; Kubes, P. An emerging role for neutrophil extracellular traps in noninfectious disease. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitkov, L.; Knopf, J.; Krunić, J.; Schauer, C.; Schoen, J.; Minnich, B.; Hannig, M.; Herrmann, M. Periodontitis-Derived Dark-NETs in Severe Covid-19. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 872695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twaddell, S.H.; Baines, K.J.; Grainge, C.; Gibson, P.G. The Emerging Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Respiratory Disease. Chest 2019, 156, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veras, F.P.; Pontelli, M.C.; Silva, C.M.; Toller-Kawahisa, J.E.; de Lima, M.; Nascimento, D.C.; Schneider, A.H.; Caetité, D.; Tavares, L.A.; Paiva, I.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2–triggered neutrophil extracellular traps mediate COVID-19 pathology. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20201129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Yalavarthi, S.; Shi, H.; Gockman, K.; Zuo, M.; Madison, J.A.; Blair, C.; Weber, A.; Barnes, B.J.; Egeblad, M.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e138999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Rivera, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dobbs, K.; Markowitz, T.E.; Dalgard, C.L.; Oler, A.J.; Claybaugh, D.R.; Draper, D.; Truong, M.; Delmonte, O.M.; et al. Multicenter analysis of neutrophil extracellular trap dysregulation in adult and pediatric COVID-19. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 7, e160332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, S.; Jagannathan, P.; Henrich, T.J.; A Sherif, Z.; Bime, C.; Quinlan, E.; A Portman, M.; Gennaro, M.; Rehman, J.; Force, R.M.P.T. Immune mechanisms underlying COVID-19 pathology and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). eLife 2023, 12, e86014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabuschnig, S.; Bronkhorst, A.J.; Holdenrieder, S.; Rodriguez, I.R.; Schliep, K.P.; Schwendenwein, D.; Ungerer, V.; Sensen, C.W. Putative Origins of Cell-Free DNA in Humans: A Review of Active and Passive Nucleic Acid Release Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitkov, L.; Klappacher, M.; Hannig, M.; Krautgartner, W.D. Extracellular neutrophil traps in periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2009, 44, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magán-Fernández, A.; O’VAlle, F.; Abadía-Molina, F.; Muñoz, R.; Puga-Guil, P.; Mesa, F. Characterization and comparison of neutrophil extracellular traps in gingival samples of periodontitis and gingivitis: A pilot study. J. Periodontal Res. 2019, 54, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, C.; Kobayashi, T.; Ito, S.; Sugita, N.; Murasawa, A.; Nakazono, K.; Yoshie, H. Circulating levels of carbamylated protein and neutrophil extracellular traps are associated with periodontitis severity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A pilot case-control study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvin, A.; Chapuis, N.; Dunsmore, G.; Goubet, A.-G.; Dubuisson, A.; Derosa, L.; Almire, C.; Hénon, C.; Kosmider, O.; Droin, N.; et al. Elevated Calprotectin and Abnormal Myeloid Cell Subsets Discriminate Severe from Mild COVID-19. Cell 2020, 182, 1401–1418.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merad, M.; Martin, J.C. Author Correction: Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: A key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulert, G.S.; Grom, A.A. Pathogenesis of Macrophage Activation Syndrome and Potential for Cytokine- Directed Therapies. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015, 66, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, R.; Sharma, B.R.; Tuladhar, S.; Williams, E.P.; Zalduondo, L.; Samir, P.; Zheng, M.; Sundaram, B.; Banoth, B.; Malireddi, R.K.S.; et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ Triggers Inflammatory Cell Death, Tissue Damage, and Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cytokine Shock Syndromes. Cell 2021, 184, 149–168.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P.-Y. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, C.; Crespo, A.; Ranjbar, S.; de Lacerda, L.B.; Lewandrowski, M.; Ingber, J.; Parry, B.; Ravid, S.; Clark, S.; Schrimpf, M.R.; et al. FcgammaR-mediated SARS-CoV-2 infection of monocytes activates inflammation. Nature 2022, 606, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J.; on behalf of theHLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020, 395, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi, H.K.; Mehra, M.R. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. J. Hear. Lung Transplant. 2020, 39, 405–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, B.K.; Francisco, E.B.; Yogendra, R.; Long, E.; Pise, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Hall, E.; Herrera, M.; Parikh, P.; Guevara-Coto, J.; et al. Persistence of SARS CoV-2 S1 Protein in CD16+ Monocytes in Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) up to 15 Months Post-Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 746021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.I.; Puritz, C.H.; Senkow, K.J.; Markov, N.S.; Diaz, E.; Jonasson, E.; Yu, Z.; Swaminathan, S.; Lu, Z.; Fenske, S.; et al. Profibrotic monocyte-derived alveolar macrophages are expanded in patients with persistent respiratory symptoms and radiographic abnormalities after COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 2024, 25, 2097–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Sherif, Z.; Gomez, C.R.; Connors, T.J.; Henrich, T.J.; Reeves, W.B.; Force, R.M.P.T. Pathogenic mechanisms of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). eLife 2023, 12, e86002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnacker, S.; Hartung, F.; Henkel, F.; Quaranta, A.; Kolmert, J.; Priller, A.; Ud-Dean, M.; Giglberger, J.; Kugler, L.M.; Pechtold, L.; et al. Correction to: Mild COVID-19 imprints a long-term inflammatory eicosanoid- and chemokine memory in monocyte-derived macrophages. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernichel-Gorbach, E.; Kornman, K.S.; Holt, S.C.; Nichols, F.; Meador, H.; Kung, J.T.; Thomas, C.A. Host Responses in Patients With Generalized Refractory Periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 1994, 65, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, L.; Soskolne, W.A.; Sela, M.N.; Offenbacher, S.; Barak, V. The secretion of PGE2, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and TNF alpha by adherent mononuclear cells from early onset periodontitis patients. J. Periodontol. 1994, 65, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Garcia, R.; Heiss, G.; Vokonas, P.S.; Offenbacher, S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J. Periodontol. 1996, 67, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ptasiewicz, M.; Grywalska, E.; Mertowska, P.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Poniewierska-Baran, A.; Niedźwiedzka-Rystwej, P.; Chałas, R. Armed to the Teeth—The Oral Mucosa Immunity System and Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, O.; Sabokbar, A.; Pocock, A.; Itonaga, I.; Fujikawa, Y.; Athanasou, N. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-11 support human osteoclast formation by a RANKL-independent mechanism. Bone 2003, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutzan, N.; Abusleme, L.; Bridgeman, H.; Greenwell-Wild, T.; Zangerle-Murray, T.; Fife, M.E.; Bouladoux, N.; Linley, H.; Brenchley, L.; Wemyss, K.; et al. On-going Mechanical Damage from Mastication Drives Homeostatic Th17 Cell Responses at the Oral Barrier. Immunity 2017, 46, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahammam, M.A.; Attia, M.S. Effects of Systemic Simvastatin on the Concentrations of Visfatin, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, and Interleukin-6 in Gingival Crevicular Fluid in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Periodontitis. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitompul, S.I.; Pikir, B.S.; Aryati; Kencono Wungu, C.D.; Supandi, S.K.; Sinta, M.E. Analysis of the Effects of IL-6-572 C/G, CRP-757 A/G, and CRP-717 T/C Gene Polymorphisms; IL-6 Levels; and CRP Levels on Chronic Periodontitis in Coronary Artery Disease in Indonesia. Genes 2023, 14, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbins, S.; Chapple, I.L.; Sapey, E.; Stockley, R. Is periodontitis a comorbidity of COPD or can associations be explained by shared risk factors/behaviors? Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, 12, 1339–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-X.; Agbana, Y.L.; Sun, Z.-S.; Fei, S.-W.; Zhao, H.-Q.; Zhou, X.-N.; Chen, J.-H.; Kassegne, K. Increased interleukin-6 is associated with long COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuwa, H.A.; Shaw, T.N.; Knight, S.B.; Wemyss, K.; McClure, F.A.; Pearmain, L.; Prise, I.; Jagger, C.; Morgan, D.J.; Khan, S.; et al. Alterations in T and B cell function persist in convalescent COVID-19 patients. Med 2021, 2, 720–735.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, P.A.; Dogra, P.; Gray, J.I.; Wells, S.B.; Connors, T.J.; Weisberg, S.P.; Krupska, I.; Matsumoto, R.; Poon, M.M.; Idzikowski, E.; et al. Longitudinal profiling of respiratory and systemic immune responses reveals myeloid cell-driven lung inflammation in severe COVID-19. Immunity 2021, 54, 797–814.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Y.; Wang, X.-M.; Xing, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.-W.; Fan, X.; Xia, P.; Fu, J.-L.; Wang, S.-Y.; et al. Single-cell landscape of immunological responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, J.; Graham, C.; Merrick, B.; Acors, S.; Pickering, S.; Steel, K.J.A.; Hemmings, O.; O’byrne, A.; Kouphou, N.; Galao, R.P.; et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetsouphanh, C.; Darley, D.R.; Wilson, D.B.; Howe, A.; Munier, C.M.L.; Patel, S.K.; Juno, J.A.; Burrell, L.M.; Kent, S.J.; Dore, G.J.; et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, M.C.; Bonham, K.S.; Anam, F.A.; Walker, T.A.; Faliti, C.E.; Ishii, Y.; Kaminski, C.Y.; Ruunstrom, M.C.; Cooper, K.R.; Truong, A.D.; et al. Chronic inflammation, neutrophil activity, and autoreactivity splits long COVID. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Files, J.K.; Boppana, S.; Perez, M.D.; Sarkar, S.; Lowman, K.E.; Qin, K.; Sterrett, S.; Carlin, E.; Bansal, A.; Sabbaj, S.; et al. Sustained cellular immune dysregulation in individuals recovering from SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e140491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVries, A.; Shambhu, S.; Sloop, S.; Overhage, J.M. One-Year Adverse Outcomes Among US Adults With Post–COVID-19 Condition vs. Those Without COVID-19 in a Large Commercial Insurance Database. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e230010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglietta, G.; Diodati, F.; Puntoni, M.; Lazzarelli, S.; Marcomini, B.; Patrizi, L.; Caminiti, C. Prognostic Factors for Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.; Wamil, M.; Kapur, S.; Alberts, J.; Badley, A.D.; Decker, G.A.; Rizza, S.A.; Banerjee, R.; Banerjee, A. Multi-organ impairment in low-risk individuals with long COVID. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudre, C.H.; Murray, B.; Varsavsky, T.; Graham, M.S.; Penfold, R.S.; Bowyer, R.C.; Pujol, J.C.; Klaser, K.; Antonelli, M.; Canas, L.S.; et al. Attributes and Predictors of Long COVID. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, M.I. Comparison of neutrophil functions in aggressive and chronic periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 2010, 53, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luntzer, K.; Lackner, I.; Weber, B.; Mödinger, Y.; Ignatius, A.; Gebhard, F.; Mihaljevic, S.-Y.; Haffner-Luntzer, M.; Kalbitz, M. Increased Presence of Complement Factors and Mast Cells in Alveolar Bone and Tooth Resorption. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernal, R.; Dutzan, N.; Hernández, M.; Chandía, S.; Puente, J.; León, R.; García, L.; Del Valle, I.; Silva, A.; Gamonal, J. High Expression Levels of Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor-Kappa B Ligand Associated With Human Chronic Periodontitis Are Mainly Secreted by CD4+ T Lymphocytes. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 1772–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso, M.J.; Deitchman, A.N.; Torres, L.; Iyer, N.S.; Munter, S.E.; Nixon, C.C.; Donatelli, J.; Thanh, C.; Takahashi, S.; Hakim, J.; et al. Long-term SARS-CoV-2-specific immune and inflammatory responses in individuals recovering from COVID-19 with and without post-acute symptoms. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glynne, P.; Tahmasebi, N.; Gant, V.; Gupta, R. Long COVID following Mild SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Characteristic T Cell Alterations and Response to Antihistamines. J. Investig. Med. 2022, 70, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlefield, K.M.; Watson, R.O.; Schneider, J.M.; Neff, C.P.; Yamada, E.; Zhang, M.; Campbell, T.B.; Falta, M.T.; Jolley, S.E.; Fontenot, A.P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells associate with inflammation and reduced lung function in pulmonary post-acute sequalae of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, B.; Boustani, K.; Ogger, P.P.; Papadaki, A.; Tonkin, J.; Orton, C.M.; Ghai, P.; Suveizdyte, K.; Hewitt, R.J.; Desai, S.R.; et al. Immuno-proteomic profiling reveals aberrant immune cell regulation in the airways of individuals with ongoing post-COVID-19 respiratory disease. Immunity 2022, 55, 542–556.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, M.C.; Ramonell, R.P.; Nguyen, D.C.; Cashman, K.S.; Saini, A.S.; Haddad, N.S.; Ley, A.M.; Kyu, S.; Howell, J.C.; Ozturk, T.; et al. Extrafollicular B cell responses correlate with neutralizing antibodies and morbidity in COVID-19. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yuan, D.; Chen, D.G.; Ng, R.H.; Wang, K.; Choi, J.; Li, S.; Hong, S.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J.; et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 2022, 185, 881–895.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastard, P.; Rosen, L.B.; Zhang, Q.; Michailidis, E.; Hoffmann, H.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Dorgham, K.; Philippot, Q.; Rosain, J.; Béziat, V.; et al. Auto-antibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 2020, 370, eabd4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, A.J.; Courau, T.; Kuhn, N.F.; Hu, K.H.; Ray, A.; Chen, W.S.; Chew, N.W.; Cleary, S.J.; Kushnoor, D.; Reeder, G.C.; et al. Publisher Correction: Global absence and targeting of protective immune states in severe COVID-19. Nature 2021, 596, E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bastard, P.; Cobat, A.; Casanova, J.-L. Human genetic and immunological determinants of critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Nature 2022, 603, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasuga, Y.; Zhu, B.; Jang, K.-J.; Yoo, J.-S. Innate immune sensing of coronavirus and viral evasion strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, S.A.; Sariol, A.; Perlman, S. Innate immune and inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2: Implications for COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.Y.; Mao, T.; Klein, J.; Dai, Y.; Huck, J.D.; Jaycox, J.R.; Liu, F.; Zhou, T.; Israelow, B.; Wong, P.; et al. Diverse functional autoantibodies in patients with COVID-19. Nature 2021, 595, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J.S.; Caricchio, R.; Casanova, J.-L.; Combes, A.J.; Diamond, B.; Fox, S.E.; Hanauer, D.A.; James, J.A.; Kanthi, Y.; Ladd, V.; et al. The intersection of COVID-19 and autoimmunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e154886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.K.; Bruiners, N.; Ukey, R.; Datta, P.; Onyuka, A.; Handler, D.; Hussain, S.; Honnen, W.; Singh, S.; Guerrini, V.; et al. Vaccination boosts protective responses and counters SARS-CoV-2-induced pathogenic memory B cells. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.E.; Feng, A.; Meng, W.; Apostolidis, S.A.; Mack, E.; Artandi, M.; Barman, L.; Bennett, K.; Chakraborty, S.; Chang, I.; et al. New-onset IgG autoantibodies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeßle, J.; Waterboer, T.; Hippchen, T.; Simon, J.; Kirchner, M.; Lim, A.; Müller, B.; Merle, U. Persistent Symptoms in Adult Patients 1 Year After Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; Thomas, I.J.; E Munter, S.; Deeks, S.G.; Henrich, T.J. Lack of Antinuclear Antibodies in Convalescent Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients With Persistent Symptoms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 2083–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moody, R.; Sonda, S.; Johnston, F.H.; Smith, K.J.; Stephens, N.; McPherson, M.; Flanagan, K.L.; Plebanski, M. Antibodies against Spike protein correlate with broad autoantigen recognition 8 months post SARS-CoV-2 exposure, and anti-calprotectin autoantibodies associated with better clinical outcomes. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 945021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervia-Hasler, C.; Brüningk, S.C.; Hoch, T.; Fan, B.; Muzio, G.; Thompson, R.C.; Ceglarek, L.; Meledin, R.; Westermann, P.; Emmenegger, M.; et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active Long Covid. Science 2024, 383, eadg7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Kajikawa, T.; Hajishengallis, E.; Maekawa, T.; Reis, E.S.; Mastellos, D.C.; Yancopoulou, D.; Hasturk, H.; Lambris, J.D. Complement-Dependent Mechanisms and Interventions in Periodontal Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, L.; Song, Y.-Q.; Zee, K.-Y.; Leung, W.K. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of complement component 5 and periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2010, 45, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Santos, A.C.P.M.; Galvão, I.; Souto, G.R.; Mesquita, R.A.; Sá, M.A.; Ferreira, A.J. The angiotensin converting enzyme 2/angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas Receptor axis as a key player in alveolar bone remodeling. Bone 2019, 128, 115041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Azzawi, I.S.; Mohammed, N.S. The Impact of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-2 (ACE-2) on Bone Remodeling Marker Osteoprotegerin (OPG) in Post-COVID-19 Iraqi Patients. Cureus 2022, 14, e29926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creecy, A.; Awosanya, O.D.; Harris, A.; Qiao, X.; Ozanne, M.; Toepp, A.J.; Kacena, M.A.; McCune, T. COVID-19 and Bone Loss: A Review of Risk Factors, Mechanisms, and Future Directions. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2024, 22, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Lau, H.E.; Xie, H.; Poon, V.K.-M.; Chan, C.C.-S.; Chu, H.; Yuan, S.; Yuen, T.T.-T.; Chik, K.K.-H.; Tsang, J.O.-L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces inflammatory bone loss in golden Syrian hamsters. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Suematsu, A.; Okamoto, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Morishita, Y.; Kadono, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Kodama, T.; Akira, S.; Iwakura, Y.; et al. Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 2673–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.A.; Knauer, M.J.; Nicholson, M.; Daley, M.; Van Nynatten, L.R.; Martin, C.; Patterson, E.K.; Cepinskas, G.; Seney, S.L.; Dobretzberger, V.; et al. Elevated vascular transformation blood biomarkers in Long-COVID indicate angiogenesis as a key pathophysiological mechanism. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, A.; Balan, I.; Yadav, S.; Matos, W.F.; Kharawala, A.; Gaddam, M.; Sarabia, N.; Koneru, S.C.; Suddapalli, S.K.; Marzban, S. Post-COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis. Cureus 2022, 14, e22770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyagi, S.C.; Pushpakumar, S.; Sen, U.; Mokshagundam, S.P.L.; Kalra, D.K.; Saad, M.A.; Singh, M. COVID-19 Mimics Pulmonary Dysfunction in Muscular Dystrophy as a Post-Acute Syndrome in Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Baidya, S.K.; Adhikari, N.; Jha, T. An updated patent review of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors (2021-present). Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 2023, 33, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet, A.; Tarrasó, J.; Rodríguez-Borja, E.; Carbonell-Asins, J.A.; Lope-Martínez, A.; Martí-Martinez, A.; Murria, R.; Safont, B.; Fernandez-Fabrellas, E.; Ros, J.A.; et al. Biomarkers of Fibrosis in Patients with COVID-19 One Year After Hospital Discharge: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaji, S.; Cholan, P.K.; Victor, D.J. An emphasis of T-cell subsets as regulators of periodontal health and disease. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2021, 7, 648–656. [Google Scholar]

- Luchian, I.; Goriuc, A.; Sandu, D.; Covasa, M. The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9, MMP-13) in Periodontal and Peri-Implant Pathological Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva-Neto, P.V.; de Carvalho, J.C.S.; Pimentel, V.E.; Pérez, M.M.; Toro, D.M.; Fraga-Silva, T.F.C.; Fuzo, C.A.; Oliveira, C.N.S.; Rodrigues, L.C.; Argolo, J.G.M.; et al. sTREM-1 Predicts Disease Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients: Involvement of Peripheral Blood Leukocytes and MMP-8 Activity. Viruses 2021, 13, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelzo, M.; Cacciapuoti, S.; Pinchera, B.; De Rosa, A.; Cernera, G.; Scialò, F.; Comegna, M.; Mormile, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Parrella, R.; et al. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) 3 and 9 as biomarkers of severity in COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, E.; Fernandez-Patron, C. Targeting MMP-Regulation of Inflammation to Increase Metabolic Tolerance to COVID-19 Pathologies: A Hypothesis. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, C.W.; Teng, Y.A. Oral mucosal dendritic cells and periodontitis: Many sides of the same coin with new twists. Periodontology 2000 2007, 45, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilensky, A.; Segev, H.; Mizraji, G.; Shaul, Y.; Capucha, T.; Shacham, M.; Hovav, A. Dendritic cells and their role in periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 2014, 20, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.; Maggi, L.; Micheletti, A.; Lazzeri, E.; Tamassia, N.; Costantini, C.; Cosmi, L.; Lunardi, C.; Annunziato, F.; Romagnani, S.; et al. Evidence for a cross-talk between human neutrophils and Th17 cells. Blood 2010, 115, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutzan, N.; Konkel, J.; Greenwell-Wild, T.; Moutsopoulos, N. Characterization of the human immune cell network at the gingival barrier. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutsopoulos, N.M.; Konkel, J.; Sarmadi, M.; Eskan, M.A.; Wild, T.; Dutzan, N.; Abusleme, L.; Zenobia, C.; Hosur, K.B.; Abe, T.; et al. Defective Neutrophil Recruitment in Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency Type I Disease Causes Local IL-17–Driven Inflammatory Bone Loss. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 229ra40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotake, S.; Yago, T.; Kawamoto, M.; Nanke, Y. Role of osteoclasts and interleukin-17 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: Crucial ‘human osteoclastology’. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2012, 30, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Azuma, T.; Motohira, H.; Kinane, D.F.; Kitetsu, S. The potential role of interleukin-17 in the immunopathology of periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.R.; Garlet, G.P.; Crippa, G.E.; Rosa, A.L.; Júnior, W.M.; Rossi, M.A.; Silva, J.S. Evidence of the presence of T helper type 17 cells in chronic lesions of human periodontal disease. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T.; Donati, M.; Zitzmann, N. B cells in periodontitis? friends or enemies? Periodontology 2000 2007, 45, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, J.R. T- and B-cell subsets in periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 2015, 69, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.-S. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialo, F.; Daniele, A.; Amato, F.; Pastore, L.; Matera, M.G.; Cazzola, M.; Castaldo, G.; Bianco, A. ACE2: The Major Cell Entry Receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torge, D.; Bernardi, S.; Arcangeli, M.; Bianchi, S. Histopathological Features of SARS-CoV-2 in Extrapulmonary Organ Infection: A Systematic Review of Literature. Pathogens 2022, 11, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgonje, A.R.; Abdulle, A.E.; Timens, W.; Hillebrands, J.L.; Navis, G.J.; Gordijn, S.J.; Bolling, M.C.; Dijkstra, G.; Voors, A.A.; Osterhaus, A.D.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Pathol. 2020, 251, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Julg, B.; Mohandas, S.; Bradfute, S.B.; Force, R.M.P.T. Viral persistence, reactivation, and mechanisms of long COVID. eLife 2023, 12, e86015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboudounya, M.M.; Heads, R.J. COVID-19 and Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4): SARS-CoV-2 May Bind and Activate TLR4 to Increase ACE2 Expression, Facilitating Entry and Causing Hyperinflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 8874339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280. e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, S.; Banerjee, P.; Bhagavatula, S.; Kushwaha, P.P.; Kumar, S. Contributions of human ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in determining host–pathogen interaction of COVID-19. J. Genet. 2021, 100, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, W.; Kubota, N.; Shimizu, T.; Saruta, J.; Fuchida, S.; Kawata, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sugimoto, M.; Yakeishi, M.; Tsukinoki, K. Existence of SARS-CoV-2 Entry Molecules in the Oral Cavity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Chen, K.; Zou, J.; Han, P.; Hao, J.; Han, Z. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front. Med. 2020, 14, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, M.; Saito, J.; Zhao, H.; Sakamoto, A.; Hirota, K.; Ma, D. Inflammation Triggered by SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 Augment Drives Multiple Organ Failure of Severe COVID-19: Molecular Mechanisms and Implications. Inflammation 2021, 44, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H.K.; Libby, P.; Ridker, P.M. COVID-19—A vascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.J.; Okuda, K.; Edwards, C.E.; Martinez, D.R.; Asakura, T.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd; Kato, T.; Lee, R.E.; Yount, B.L.; Mascenik, T.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract. Cell 2020, 182, 429–446 e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.M.; Wang, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, P.H. Increasing host cellular receptor-angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression by coronavirus may facilitate 2019-nCoV (or SARS-CoV-2) infection. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2693–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.C.; Sausville, E.L.; Girish, V.; Yuan, M.L.; Vasudevan, A.; John, K.M.; Sheltzer, J.M. Cigarette Smoke Exposure and Inflammatory Signaling Increase the Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 in the Respiratory Tract. Dev. Cell 2020, 53, 514–529.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C.G.K.; Allon, S.J.; Nyquist, S.K.; Mbano, I.M.; Miao, V.N.; Tzouanas, C.N.; Cao, Y.; Yousif, A.S.; Bals, J.; Hauser, B.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 Is an Interferon-Stimulated Gene in Human Airway Epithelial Cells and Is Detected in Specific Cell Subsets across Tissues. Cell 2020, 181, 1016–1035.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.K.; Juno, J.A.; Lee, W.S.; Wragg, K.M.; Hogarth, P.M.; Kent, S.J.; Burrell, L.M. Plasma ACE2 activity is persistently elevated following SARS-CoV-2 infection: Implications for COVID-19 pathogenesis and consequences. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2003730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proal, A.D.; VanElzakker, M.B.; Aleman, S.; Bach, K.; Boribong, B.P.; Buggert, M.; Cherry, S.; Chertow, D.S.; Davies, H.E.; Dupont, C.L.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 reservoir in post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 1616–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaebler, C.; Wang, Z.; Lorenzi, J.C.C.; Muecksch, F.; Finkin, S.; Tokuyama, M.; Cho, A.; Jankovic, M.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Oliveira, T.Y.; et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 591, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, G.D.; Lazarini, F.; Levallois, S.; Hautefort, C.; Michel, V.; Larrous, F.; Verillaud, B.; Aparicio, C.; Wagner, S.; Gheusi, G.; et al. COVID-19–related anosmia is associated with viral persistence and inflammation in human olfactory epithelium and brain infection in hamsters. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabf8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Doyle, M.E.; Liu, Q.-R.; Appleton, A.; O’connell, J.F.; Weng, N.-P.; Egan, J.M. Long-Term Dysfunction of Taste Papillae in SARS-CoV-2. NEJM Évid. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.C.; da Fonseca, J.G.; Miller, L.M.; Manenti, L.; Angst, P.D.M.; Lamers, M.L.; Brum, I.S.; Nunes, L.N. SARS-CoV-2 RNA in dental biofilms: Supragingival and subgingival findings from inpatients in a COVID-19 intensive care unit. J. Periodontol. 2022, 93, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesan, J.T.; Warner, B.M.; Byrd, K.M. The “oral” history of COVID-19: Primary infection, salivary transmission, and post-acute implications. J. Periodontol. 2021, 92, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, D.; Martínez-Sanz, J.; Sainz, T.; Calvo, C.; Méndez-Echevarría, A.; Moreno, E.; Blázquez-Gamero, D.; Vizcarra, P.; Rodríguez, M.; Jenkins, R.; et al. Differences in saliva ACE2 activity among infected and non-infected adult and pediatric population exposed to SARS-CoV-2. J. Infect. 2022, 85, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhong, L.; Deng, J.; Peng, J.; Dan, H.; Zeng, X.; Li, T.; Chen, Q. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, A.; Nowzari, H.; Slots, J. Herpesviruses in periodontal pocket and gingival tissue specimens. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 2000, 15, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappuyns, I.; Gugerli, P.; Mombelli, A. Viruses in periodontal disease—A review. Oral Dis. 2005, 11, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, Z.; Gaudin, A.; Struillou, X.; Amador, G.; Soueidan, A. Periodontal pockets: A potential reservoir for SARS-CoV-2? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 143, 109907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, J.E.; Okyay, R.A.; Licht, W.E.; Hurley, D.J. Investigation of Long COVID Prevalence and Its Relationship to Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation. Pathogens 2021, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alramadhan, S.A.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Cohen, D.M.; Islam, M.N. Oral Hairy Leukoplakia in Immunocompetent Patients Revisited with Literature Review. Head Neck Pathol. 2021, 15, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, B.J.H.; Schaal, D.L.; Nkadi, E.H.; Scott, R.S. EBV Association with Lymphomas and Carcinomas in the Oral Compartment. Viruses 2022, 14, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulani, C.; Auerkari, E.I.; Masulili, S.L.C.; Soeroso, Y.; Santoso, W.D.; Kusdhany, L.S. Association between Epstein-Barr virus and periodontitis: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.-S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.-S.; Bartley, C.M.; et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.H.; Steinman, L. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluso, M.J.; Mitchell, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Takahashi, S.; Hoh, R.; Tai, V.; Durstenfeld, M.S.; Hsue, P.Y.; Kelly, J.D.; Martin, J.N.; et al. Low Prevalence of Interferon α Autoantibodies in People Experiencing Symptoms of Post–Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Conditions, or Long COVID. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 227, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, P.; Tang, J.; Yang, B.; Li, H.; Liang, M.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis Correlates With Long COVID-19 at One-Year After Discharge. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, Y.; Motooka, D.; Kawasaki, T.; Oki, H.; Noda, Y.; Adachi, Y.; Niitsu, T.; Okamoto, S.; Tanaka, K.; Fukushima, K.; et al. Longitudinal alterations of the gut mycobiota and microbiota on COVID-19 severity. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, V.; Suryawanshi, R.K.; Tasoff, P.; McCavitt-Malvido, M.; Kumar, R.G.; Murray, V.W.; Noecker, C.; Bisanz, J.E.; Hswen, Y.; Ha, C.W.Y.; et al. Mild SARS-CoV-2 infection results in long-lasting microbiota instability. mBio 2023, 14, e0088923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollner, A.; Koch, R.; Jukic, A.; Pfister, A.; Meyer, M.; Rössler, A.; Kimpel, J.; Adolph, T.E.; Tilg, H. Postacute COVID-19 is Characterized by Gut Viral Antigen Persistence in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 495–506.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.-Y.; Lei, X.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, D.-H.; Li, J.-Q.; Lu, L.-Y.; Laila, U.E.; Cui, C.-Y.; Xu, Z.-X.; Jian, Y.-P. Development and management of gastrointestinal symptoms in long-term COVID-19. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1278479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paine, S.K.; Rout, U.K.; Bhattacharyya, C.; Parai, D.; Alam, M.; Nanda, R.R.; Tripathi, D.; Choudhury, P.; Kundu, C.N.; Pati, S.; et al. Temporal dynamics of oropharyngeal microbiome among SARS-CoV-2 patients reveals continued dysbiosis even after Viral Clearance. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemquerer, L.M.; Oliveira, S.R.; de Arruda, J.A.A.; Costa, F.P.D.; Miguita, L.; Bemquerer, A.L.M.; de Sena, A.C.V.P.; de Souza, A.F.; Mendes, D.F.; Schneider, A.H.; et al. Clinical, immunological, and microbiological analysis of the association between periodontitis and COVID-19: A case–control study. Odontology 2024, 112, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haran, J.P.; Bradley, E.; Zeamer, A.L.; Cincotta, L.; Salive, M.-C.; Dutta, P.; Mutaawe, S.; Anya, O.; Meza-Segura, M.; Moormann, A.M.; et al. Inflammation-type dysbiosis of the oral microbiome associates with the duration of COVID-19 symptoms and long COVID. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 6, e152346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, A. Is There a Similarity in Serum Cytokine Profile between Patients with Periodontitis or 2019-Novel Coronavirus Infection?—A Scoping Review. Biology 2023, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz-Junior, C.M.; Santos, A.C.; Gonçalves, M.R.; Brito, C.B.; Barrioni, B.; Almeida, P.J.; Gonçalves-Pereira, M.H.; Silva, T.; Oliveira, S.R.; Pereira, M.M.; et al. Acute coronavirus infection triggers a TNF-dependent osteoporotic phenotype in mice. Life Sci. 2023, 324, 121750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartold, P.M.; Mariotti, A. The Future of Periodontal-Systemic Associations: Raising the Standards. Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2017, 4, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hujoel, P.P.; Cunha-Cruz, J.; Kressin, N.R. Spurious associations in oral epidemiological research: The case of dental flossing and obesity. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2023 Disease and Injury and Risk Factor Collaborators. Burden of 375 diseases and injuries, risk-attributable burden of 88 risk factors, and healthy life expectancy in 204 countries and territories, including 660 subnational locations, 1990–2023: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1873–1922.

- Mainas, G.; Nibali, L.; Ide, M.; Al Mahmeed, W.; Al-Rasadi, K.; Al-Alawi, K.; Banach, M.; Banerjee, Y.; Ceriello, A.; Cesur, M.; et al. Associations between Periodontitis, COVID-19, and Cardiometabolic Complications: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Evidence. Metabolites 2022, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Immune—Inflammatory Components | Long-COVID | Periodontitis |

|---|---|---|

| Dendritic Cells | ↓ | ↑ |

| IFN-α Production | ↓ | ↑ or ↓ |

| Neutrophils | ↑ | ↑ |

| Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and other Inflammatory mediator productions—“Cytokine Storm” | ↑ IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, G-CSF, MCP-1, TNF-α | ↑ IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-17, IL-21, IL-22, IL-23, PGE2, TNF-α |

| Natural Killer Cells | ↓ | ↑ |

| Complement Factors | ↑ or ↓ ↑ Soluble C5bC6 complexes, ↓ C7 | ↑ ↑ C3, C3a, C5, C5a |

| Total Number of T and B Cells | ↑ In the majority of affected: persistent immune exhaustion; maintained elevation (i.e., delayed or dysregulated recovery), or late in some individuals (e.g., the Elderly or Immunocompromised) | ↑ |

| Neutralizing Antibodies | Acute-phase viral-load dependent (e.g., elevated in individuals with a high peak infective viral load) | ↑ |

| CD4+ T Cells | ↑ or ↓ ↓ In the majority of affected; ↑ Among the Elderly | ↑ |

| CD8+ T Cells | ↑ or ↓ Inconsistent: ↓ In the majority; but maintained elevated or with late ↑ in some individuals (e.g., the Elderly or Immunocompromised) | Less noticeable in the literature |

| Th17 | ↑ | ↑ |

| MMPs (e.g., MMP-8, MMP-9) | ↑ | ↑ |

| RANKL | ↑ | ↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andriankaja, O.M.; Whiteheart, S.; Mattos, M.B.d.A. Biological Plausibility Between Long-COVID and Periodontal Disease Development or Progression. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123023

Andriankaja OM, Whiteheart S, Mattos MBdA. Biological Plausibility Between Long-COVID and Periodontal Disease Development or Progression. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123023

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndriankaja, Oelisoa Mireille, Sidney Whiteheart, and Marcelo Barbosa de Accioly Mattos. 2025. "Biological Plausibility Between Long-COVID and Periodontal Disease Development or Progression" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123023

APA StyleAndriankaja, O. M., Whiteheart, S., & Mattos, M. B. d. A. (2025). Biological Plausibility Between Long-COVID and Periodontal Disease Development or Progression. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123023