Targeting Cathepsins in Neurodegeneration: Biochemical Advances

Abstract

1. The Lysosomal System and Its Role in Proteostasis and Neuronal Health

- Macroautophagy, the most studied form, involves the formation of double-membraned autophagosomes that sequester damaged organelles or protein aggregates and subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes where degradation occurs.

- Microautophagy, in which invaginations of the lysosomal membrane directly engulf cytoplasmic content.

- Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), a selective process whereby cytosolic proteins containing the KFERQ motif are recognized by HSPA8 and translocated into the lysosome via the LAMP-2A receptor.

2. The Role of Cathepsins in Neurons and Their Alteration Under Stress

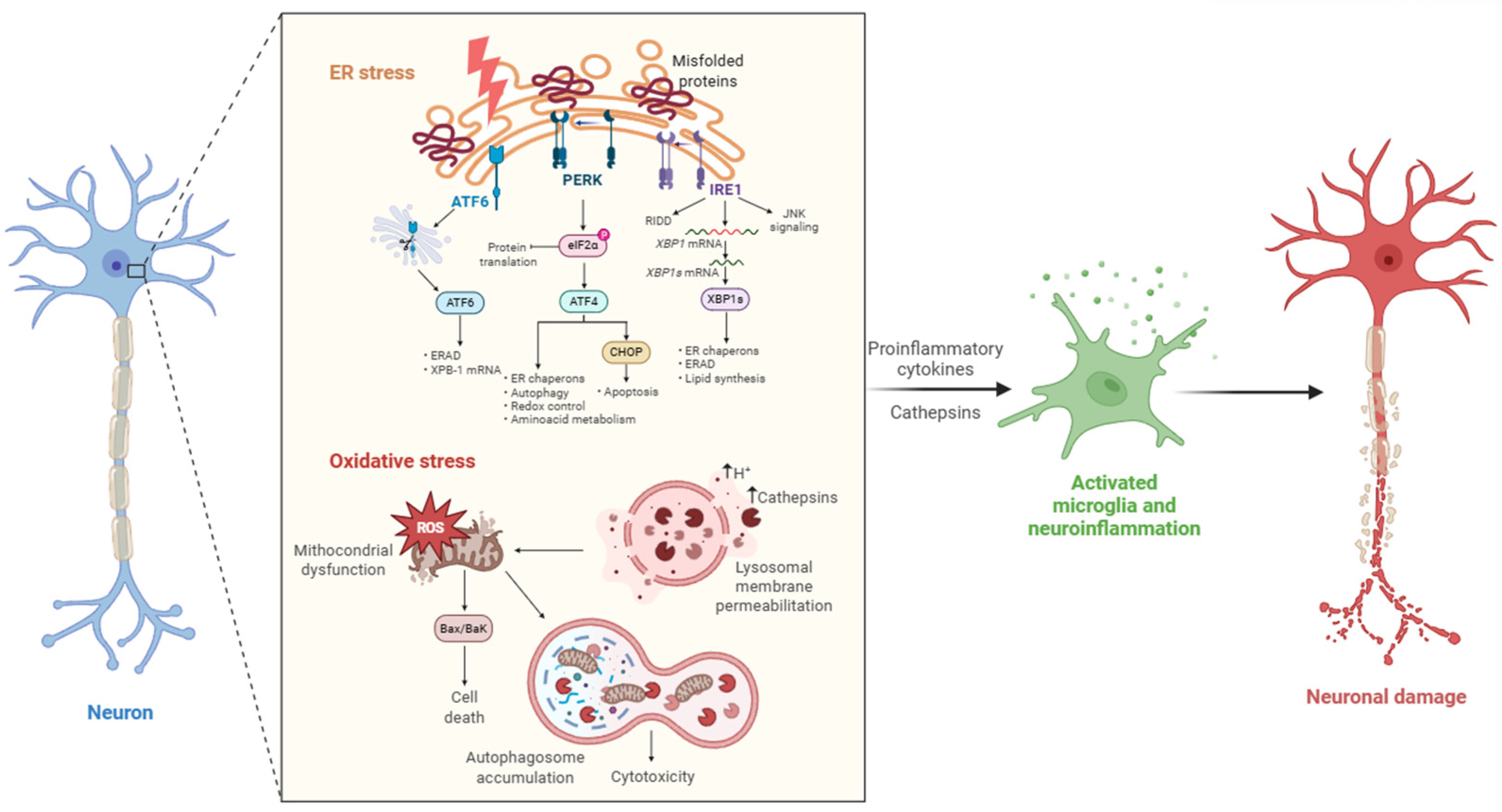

Stress-Induced Dysregulation

- -

- ER Stress

- -

- Oxidative Stress

- -

- Mitochondrial dysfunction

- -

- ER Mitochondria Crosstalk and Neuroinflammation

3. Cathepsins Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases

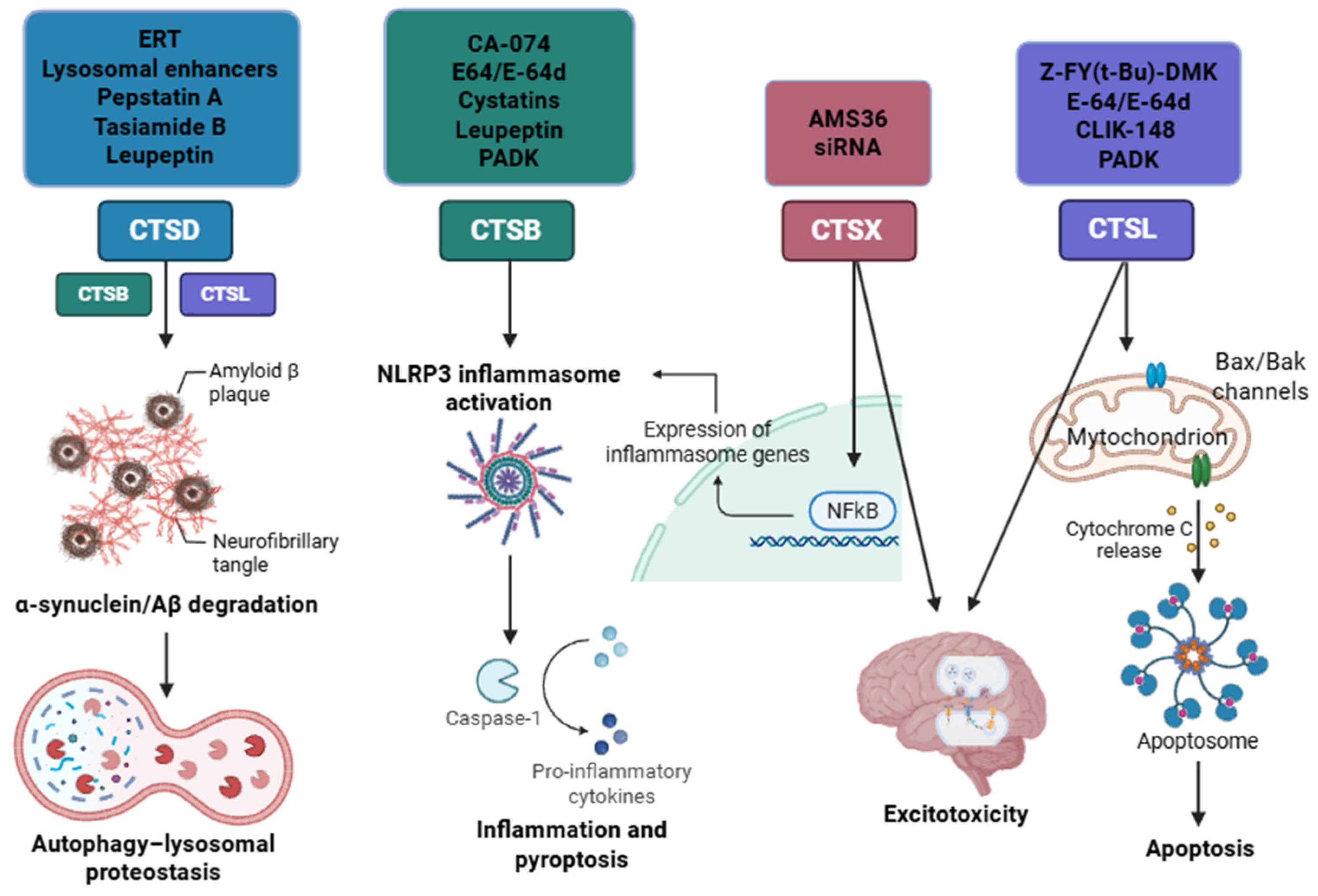

3.1. Mechanism of Cathepsin Inhibition and Principal Classes of Inhibitors

3.1.1. Aspartic Proteases (CTSD and CTSE)

3.1.2. Serine Proteases (CTSA and CTSG)

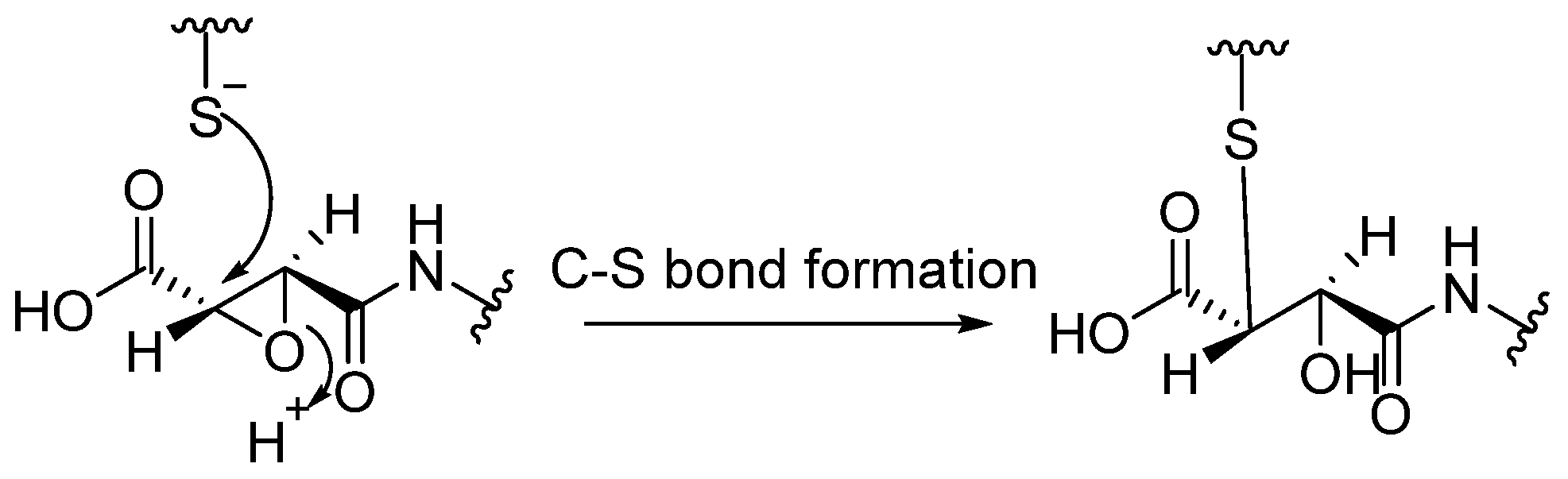

3.1.3. Cysteine Proteases (CTSB, CTSL, CTSC, CTSK, CTSH, CTSZ/X)

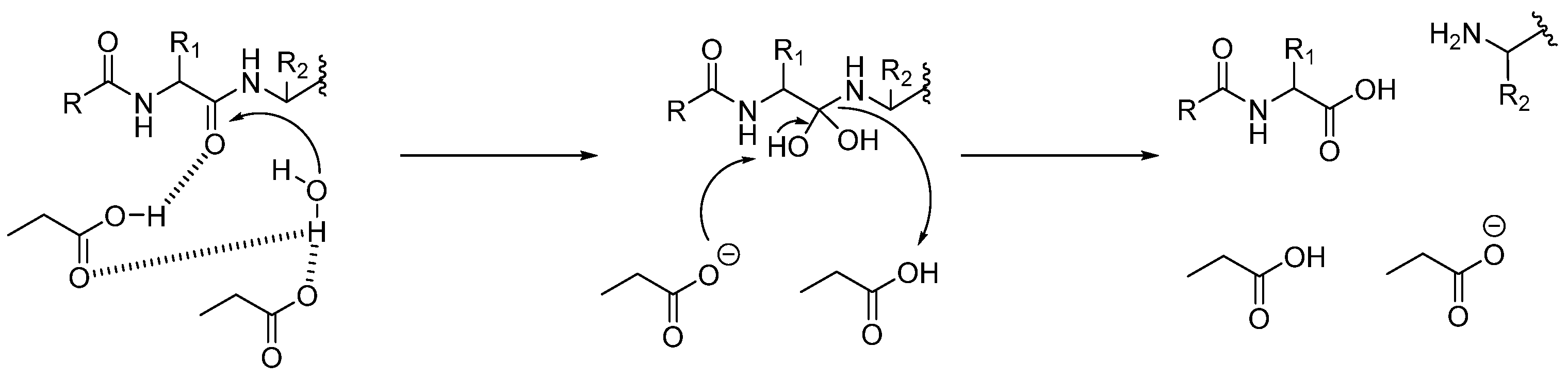

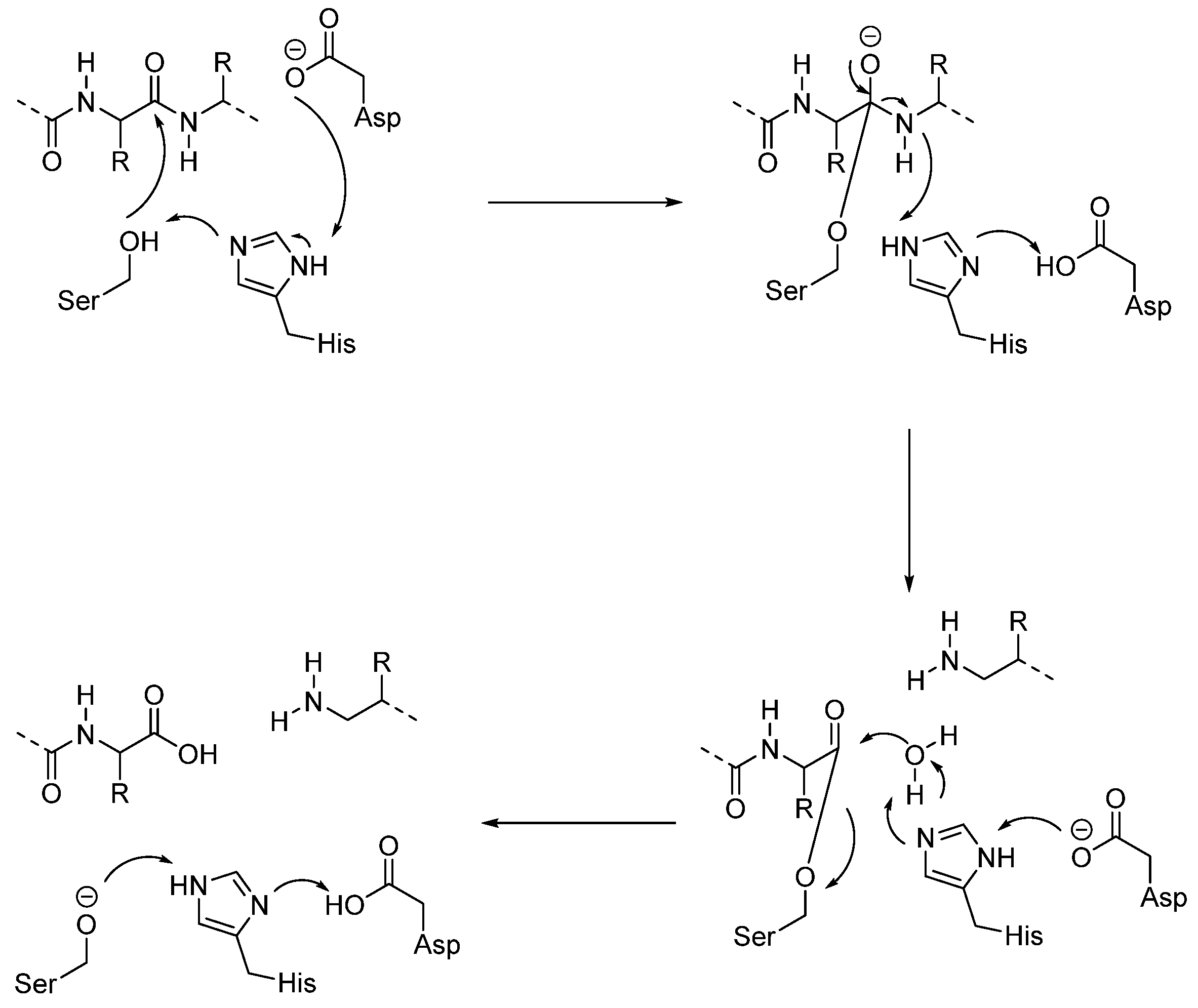

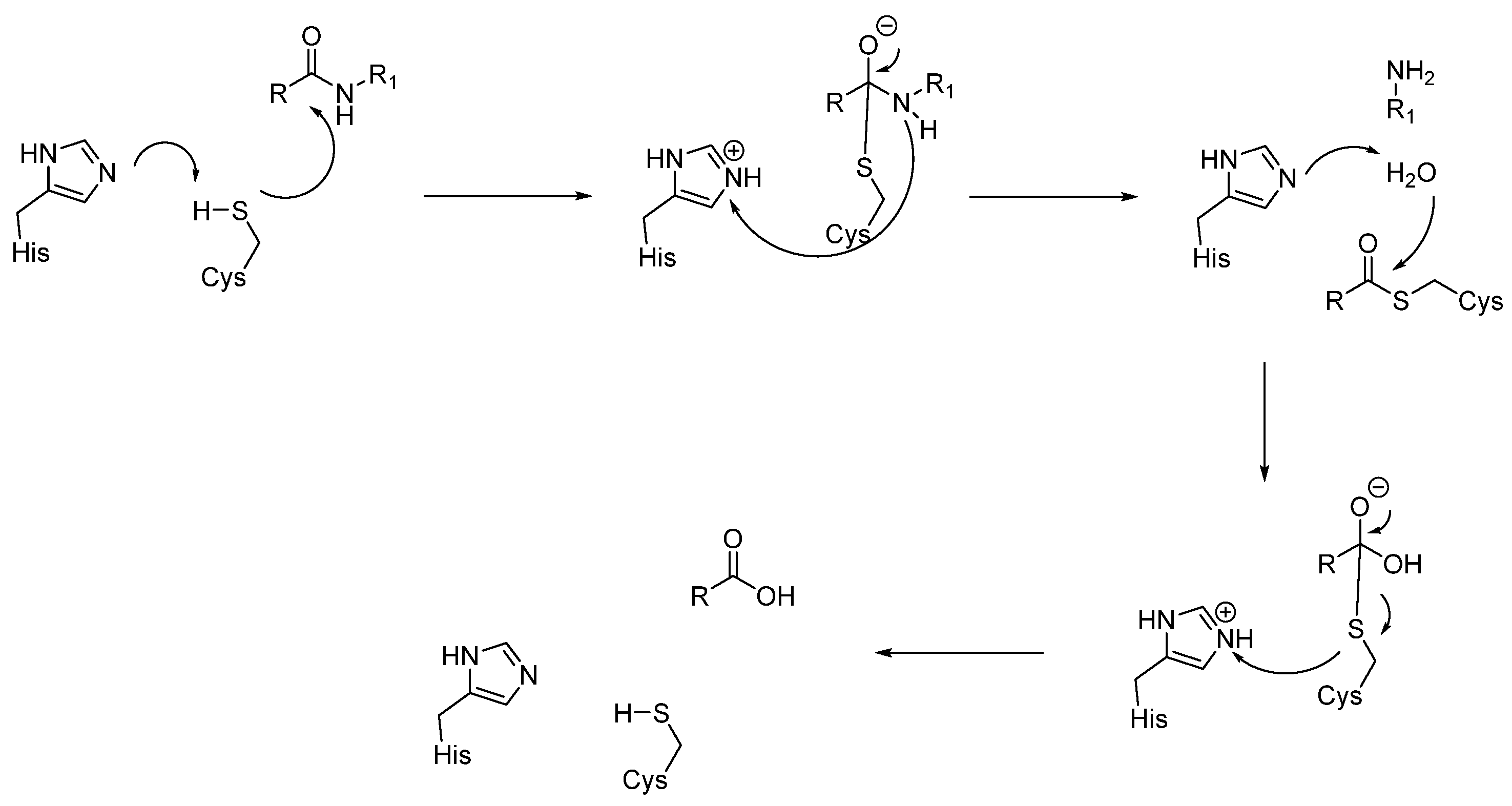

- Histidine acts as a base and deprotonates the thiol from cysteine, forming the thiolate anion.

- The thiolate attacks the carbonyl group of the substrate, giving the acyl-enzyme intermediate.

- At this point, the tetrahedral intermediate is stabilized by an oxyanion hole. In fact, the tetrahedral intermediate is characterized by a negatively charged oxygen atom, which is stabilized by hydrogen bonds from the amide backbone, typically from NH groups of residues near the active site cleft.

- -

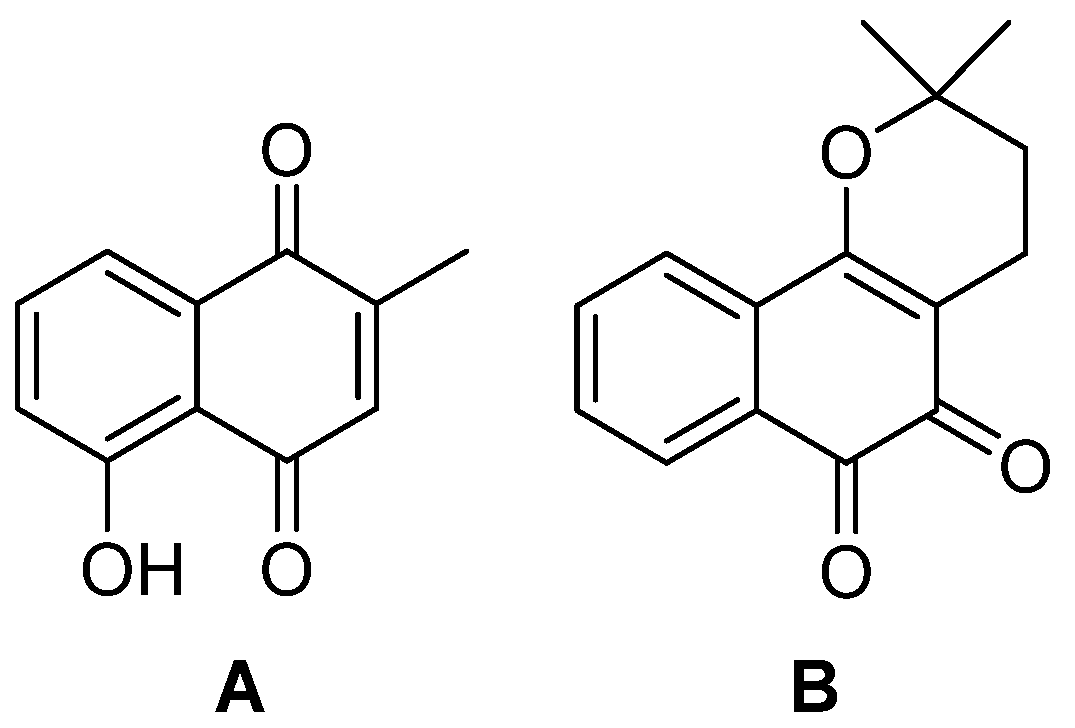

- Aldehyde inhibitors

- -

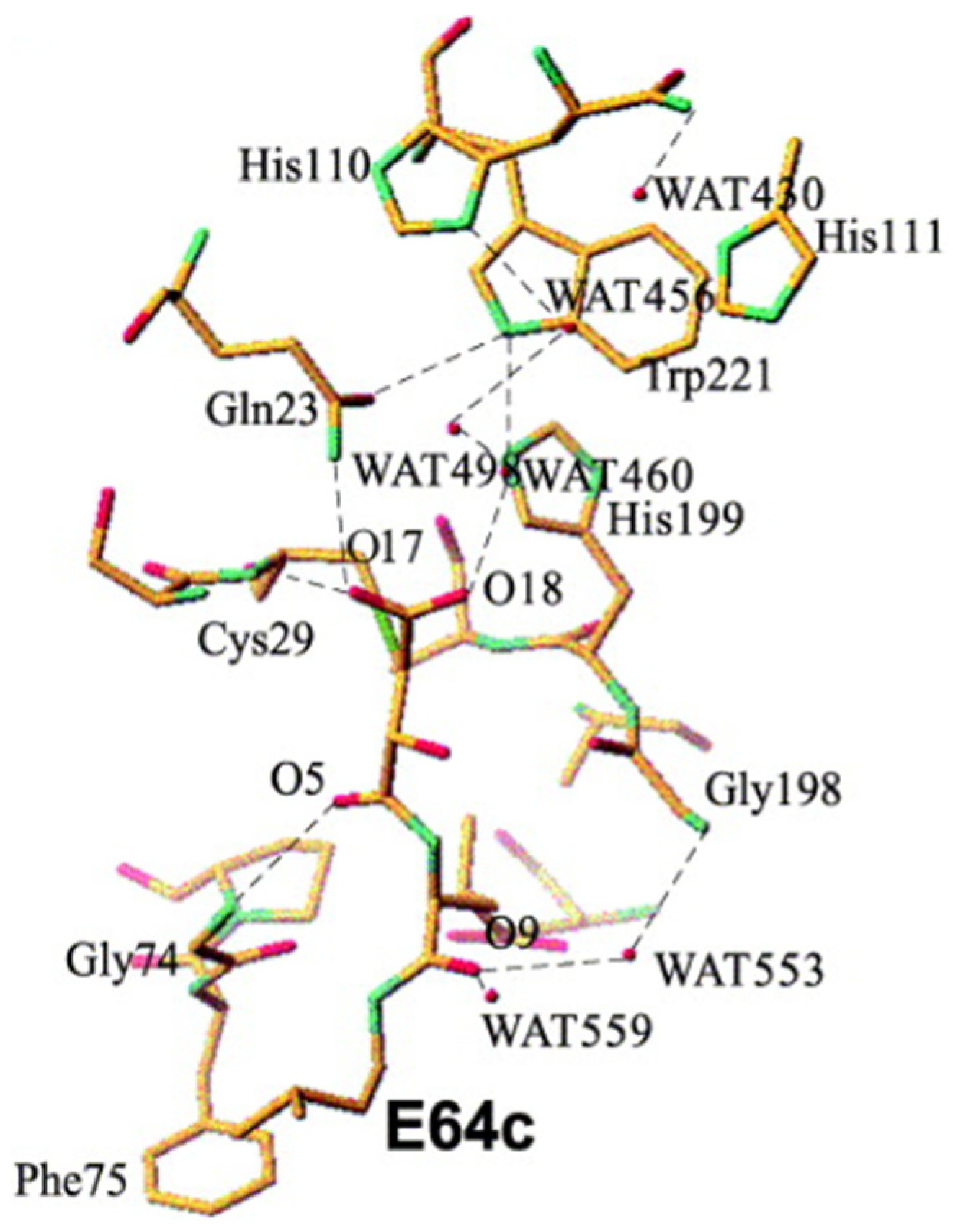

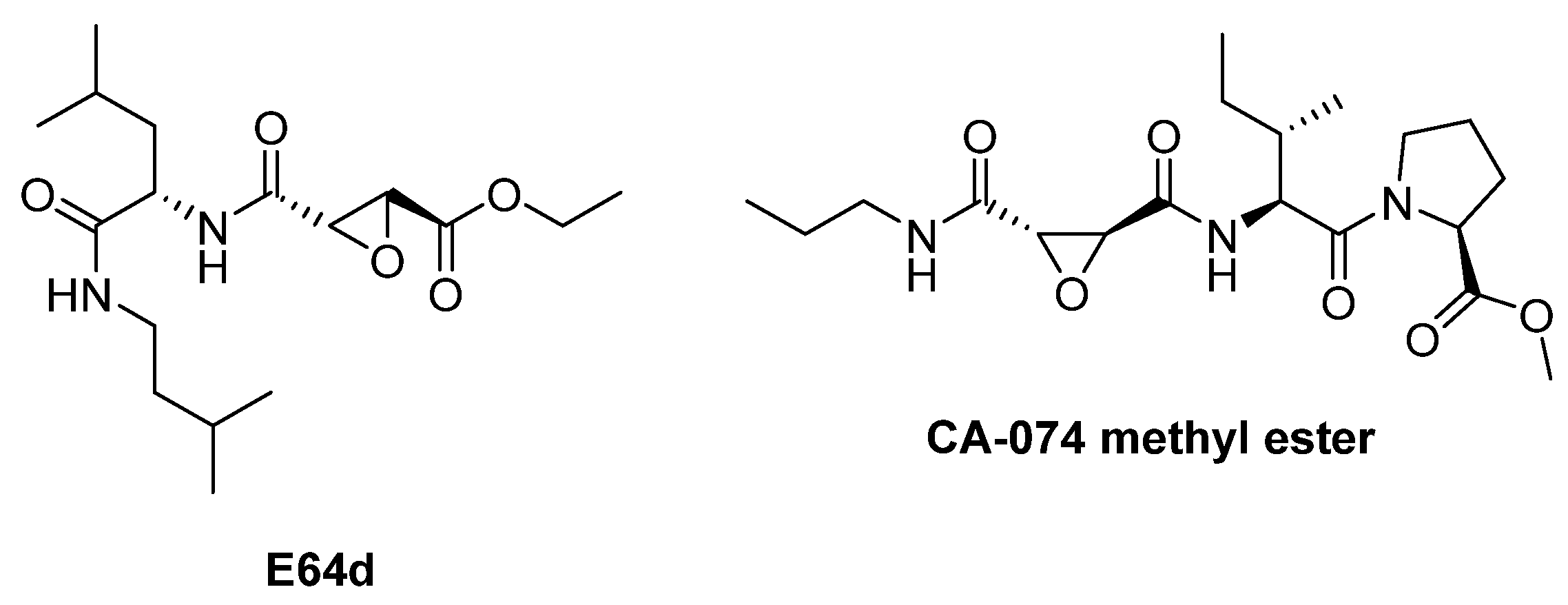

- Epoxysuccinate inhibitors

- -

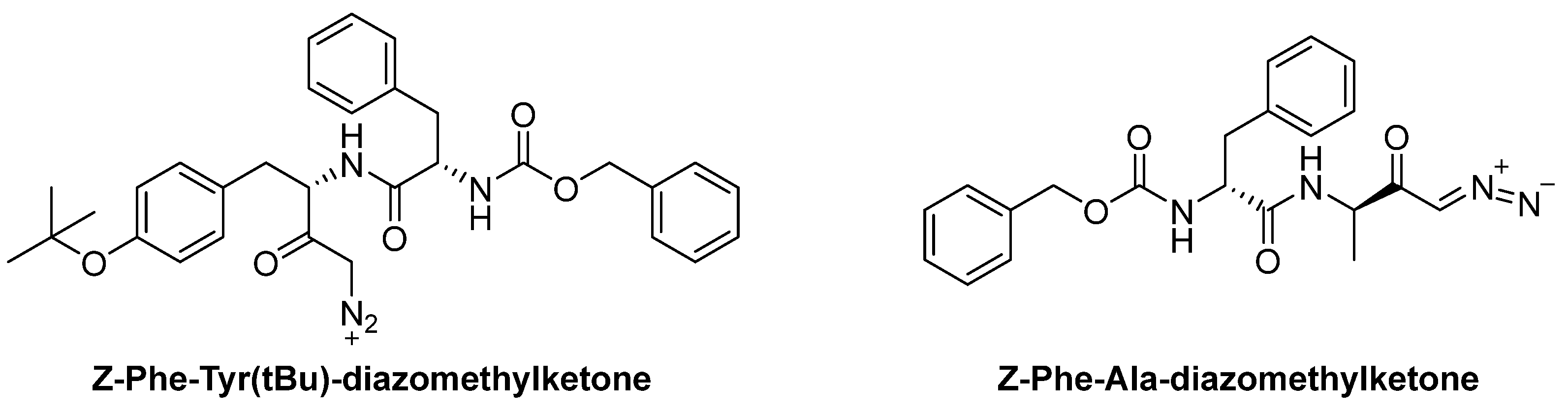

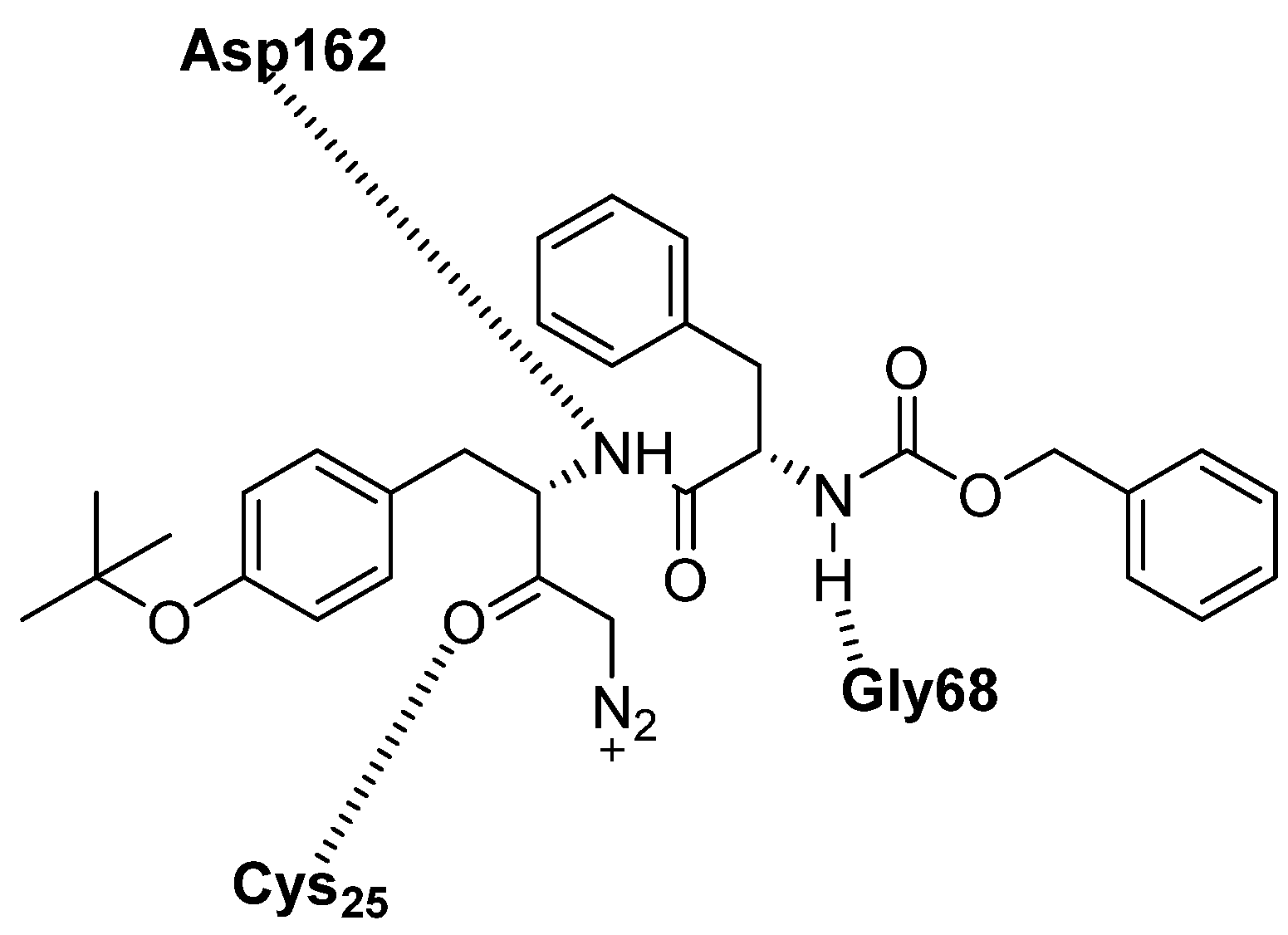

- Diazomethylketone inhibitors

4. Targeting Cathepsins as a Therapeutic Approach

4.1. Role of Cathepsins in Parkinson’s Disease and Possible Therapeutic Approaches

4.2. Role of Cathepsins in Alzheimer’s Disease and Possible Therapeutic Approaches

4.3. Role of Cathepsins in Huntington’s Disease and Possible Therapeutic Approaches

4.4. Role of Cathepsins in Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Possible Therapeutic Approaches

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikic, I.; Elazar, Z. Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzych, K.R.; Klionsky, D.J. An overview of autophagy: Morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 2014, 20, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frake, R.A.; Ricketts, T.; Menzies, F.M.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Autophagy and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, D.; Konieczny, M.; Różycka, A.; Chrzanowski, K.; Owecki, W.; Kalinowski, J.; Stepura, M.; Jagodziński, P.; Dorszewska, J. Cathepsins in Neurological Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conus, S.; Simon, H.U. Cathepsins and their involvement in immune responses. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010, 140, w13042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, O.C.; Joyce, J.A. Cysteine cathepsin proteases: Regulators of cancer progression and therapeutic response. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 712–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. The role of autophagy in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saftig, P.; Klumperman, J. Lysosome biogenesis and lysosomal membrane proteins: Trafficking meets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, F.M.; Fleming, A.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, F.; Bucci, C. Multiple Roles of the Small GTPase Rab7. Cells 2016, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U.; Lommatzsch, J.; Küchle, M.; Konstas, A.G.; Naumann, G.O. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in aqueous humor of patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome/glaucoma and primary open-angle glaucoma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2003, 44, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, H.; Zhang, J.; Koike, M.; Nishioku, T.; Okamoto, Y.; Kominami, E.; von Figura, K.; Peters, C.; Yamamoto, K.; Saftig, P.; et al. Involvement of nitric oxide released from microglia-macrophages in pathological changes of cathepsin D-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 7526–7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repnik, U.; Hafner Česen, M.; Turk, B. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death: Concepts and challenges. Mitochondrion 2014, 19, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietri, M.; Miranda, M.R.; Amodio, G.; Ciaglia, T.; Bertamino, A.; Campiglia, P.; Remondelli, P.; Vestuto, V.; Moltedo, O. The Link Between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Lysosomal Dysfunction Under Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, E.; Baldeiras, I.; Ferreira, I.L.; Costa, R.O.; Rego, A.C.; Pereira, C.F.; Oliveira, C.R. Mitochondrial- and endoplasmic reticulum-associated oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: From pathogenesis to biomarkers. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 735206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondani, M.; Roginski, A.C.; Ribeiro, R.T.; de Medeiros, M.P.; Hoffmann, C.I.H.; Wajner, M.; Leipnitz, G.; Seminotti, B. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, ER stress and mitochondria-ER crosstalk alterations in a chemical rat model of Huntington’s disease: Potential benefits of bezafibrate. Toxicol. Lett. 2023, 381, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheper, W.; Hoozemans, J.J. The unfolded protein response in neurodegenerative diseases: A neuropathological perspective. Acta Neuropathol. 2015, 130, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P. Understanding the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) Pathway: Insights into Neuropsychiatric Disorders and Therapeutic Potentials. Biomol. Ther. 2024, 32, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merighi, A.; Lossi, L. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling and Neuronal Cell Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghero, G.; Pugliatti, M.; Marrosu, F.; Marrosu, M.G.; Murru, M.R.; Floris, G.; Cannas, A.; Parish, L.D.; Cau, T.B.; Loi, D.; et al. ATXN2 is a modifier of phenotype in ALS patients of Sardinian ancestry. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 2906.e1-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, M.; Mallucci, G.R. Review: Modulating the unfolded protein response to prevent neurodegeneration and enhance memory. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2015, 41, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; Gu, R.; Han, R.; Li, Z.; Xu, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in diseases. MedComm (2020) 2024, 5, e701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinheckel, T.; Tholen, M. Low-level lysosomal membrane permeabilization for limited release and sublethal functions of cathepsin proteases in the cytosol and nucleus. FEBS Open Bio 2022, 12, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.R.; Vestuto, V.; Moltedo, O.; Manfra, M.; Campiglia, P.; Pepe, G. The Ion Channels Involved in Oxidative Stress-Related Gastrointestinal Diseases. Oxygen 2023, 3, 336–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, D.; Sharma, V.; Rath, S.K.; Rai, U.; Panigrahi, N. Functional implications and therapeutic targeting of androgen response elements in prostate cancer. Biochimie 2023, 214, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ma, M.; Li, D.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; He, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.; Hou, X.; et al. Sulfiredoxin-1 attenuates injury and inflammation in acute pancreatitis through the ROS/ER stress/Cathepsin B axis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Yan, Z.; Zhu, Z. Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 604240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Ahumada-Castro, U.; Sanhueza, M.; Gonzalez-Billault, C.; Court, F.A.; Cárdenas, C. Mitochondria and Calcium Regulation as Basis of Neurodegeneration Associated with Aging. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codolo, G.; Plotegher, N.; Pozzobon, T.; Brucale, M.; Tessari, I.; Bubacco, L.; de Bernard, M. Triggering of inflammasome by aggregated α-synuclein, an inflammatory response in synucleinopathies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lim, H.S.; Masliah, E.; Lee, H.J. Protein aggregate spreading in neurodegenerative diseases: Problems and perspectives. Neurosci Res. 2011, 70, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pišlar, A.; Kos, J. Cysteine cathepsins in neurological disorders. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 49, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Fei, X.; Zhuang, W.; Fang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Liang, Z. Cathepsin L is involved in 6-hydroxydopamine induced apoptosis of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 2011, 1387, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suire, C.N.; Abdul-Hay, S.O.; Sahara, T.; Kang, D.; Brizuela, M.K.; Saftig, P.; Dickson, D.W.; Rosenberry, T.L.; Leissring, M.A. Cathepsin D regulates cerebral Aβ42/40 ratios via differential degradation of Aβ42 and Aβ40. Alzheimers. Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, V.; Lindfors, M.; Ng, J.; Paetau, A.; Swinton, E.; Kolodziej, P.; Boston, H.; Saftig, P.; Woulfe, J.; Feany, M.B.; et al. Cathepsin D expression level affects alpha-synuclein processing, aggregation, and toxicity in vivo. Mol. Brain 2009, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Q.; Ouyang, X.; Schneider, L.; Zhang, J. Reduction of mutant huntingtin accumulation and toxicity by lysosomal cathepsins D and B in neurons. Mol. Neurodegener. 2011, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mijanovic, O.; Petushkova, A.I.; Brankovic, A.; Turk, B.; Solovieva, A.B.; Nikitkina, A.I.; Bolevich, S.; Timashev, P.S.; Parodi, A.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr. Cathepsin D-Managing the Delicate Balance. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidoni, C.; Follo, C.; Savino, M.; Melone, M.A.; Isidoro, C. The Role of Cathepsin D in the Pathogenesis of Human Neurodegenerative Disorders. Med. Res. Rev. 2016, 36, 845–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevlever, D.; Jiang, P.; Yen, S.H. Cathepsin D is the main lysosomal enzyme involved in the degradation of alpha-synuclein and generation of its carboxy-terminally truncated species. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 9678–9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto Huarcaya, S.; Drobny, A.; Marques, A.R.A.; Di Spiezio, A.; Dobert, J.P.; Balta, D.; Werner, C.; Rizo, T.; Gallwitz, L.; Bub, S.; et al. Recombinant pro-CTSD (cathepsin D) enhances SNCA/α-Synuclein degradation in α-Synucleinopathy models. Autophagy 2022, 18, 1127–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Sapp, E.; Cuiffo, B.G.; Sobin, L.; Yoder, J.; Kegel, K.B.; Qin, Z.H.; Detloff, P.; Aronin, N.; DiFiglia, M. Lysosomal proteases are involved in generation of N-terminal huntingtin fragments. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 22, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.P.; Liu, X.H.; Ren, M.J.; Liu, X.T.; Shi, X.Q.; Li, M.L.; Li, S.A.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.D.; Wu, Y.; et al. Neuronal cathepsin S increases neuroinflammation and causes cognitive decline via CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis and JAK2-STAT3 pathway in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pišlar, A.; Bolčina, L.; Kos, J. New Insights into the Role of Cysteine Cathepsins in Neuroinflammation. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terada, K.; Yamada, J.; Hayashi, Y.; Wu, Z.; Uchiyama, Y.; Peters, C.; Nakanishi, H. Involvement of cathepsin B in the processing and secretion of interleukin-1beta in chromogranin A-stimulated microglia. Glia 2010, 58, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, G.; Reinheckel, T.; Ni, J.; Wu, Z.; Kindy, M.; Peters, C.; Hook, V. Cathepsin B Gene Knockout Improves Behavioral Deficits and Reduces Pathology in Models of Neurologic Disorders. Pharmacol. Rev. 2022, 74, 600–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, V.; Funkelstein, L.; Wegrzyn, J.; Bark, S.; Kindy, M.; Hook, G. Cysteine Cathepsins in the secretory vesicle produce active peptides: Cathepsin L generates peptide neurotransmitters and cathepsin B produces beta-amyloid of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1824, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohda, C.; Tohda, M. Extracellular cathepsin L stimulates axonal growth in neurons. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Qian, Y.; Xiao, Q. Inhibition of cathepsin L alleviates the microglia-mediated neuroinflammatory responses through caspase-8 and NF-κB pathways. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 62, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brguljan, P.M.; Turk, V.; Nina, C.; Brzin, J.; Krizaj, I.; Popovic, T. Human brain cathepsin H as a neuropeptide and bradykinin metabolizing enzyme. Peptides 2003, 24, 1977–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Reinheckel, T.; Turk, V.; Nakanishi, H. Cathepsin H deficiency decreases hypoxia-ischemia-induced hippocampal atrophy in neonatal mice through attenuated TLR3/IFN-β signaling. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Wu, X.; Fan, B.; Li, N.; Lin, Y.; Yao, Y.; Ma, J. Up-regulation of microglial cathepsin C expression and activity in lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liuzzo, J.P.; Petanceska, S.S.; Devi, L.A. Neurotrophic factors regulate cathepsin S in macrophages and microglia: A role in the degradation of myelin basic protein and amyloid beta peptide. Mol. Med. 1999, 5, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pišlar, A.; Božić, B.; Zidar, N.; Kos, J. Inhibition of cathepsin X reduces the strength of microglial-mediated neuroinflammation. Neuropharmacology 2017, 114, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pišlar, A.; Nedeljković, B.B.; Perić, M.; Jakoš, T.; Zidar, N.; Kos, J. Cysteine Peptidase Cathepsin X as a Therapeutic Target for Simultaneous TLR3/4-mediated Microglia Activation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 2258–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Zhao, M.; Yan, C.; Kong, W.; Lan, F.; Narengaowa; Zhao, S.; Yang, Q.; Bai, Z.; Qing, H.; et al. Cathepsin B in programmed cell death machinery: Mechanisms of execution and regulatory pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pišlar, A.; Tratnjek, L.; Glavan, G.; Zidar, N.; Živin, M.; Kos, J. Neuroinflammation-Induced Upregulation of Glial Cathepsin X Expression and Activity in vivo. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 575453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, E.R.O.; Campden, R.I.; Ewanchuk, B.W.; Tailor, P.; Balce, D.R.; McKenna, N.T.; Greene, C.J.; Warren, A.L.; Reinheckel, T.; Yates, R.M. A role for cathepsin Z in neuroinflammation provides mechanistic support for an epigenetic risk factor in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Guajardo, V.; Tentillier, N.; Romero-Ramos, M. The relation between α-synuclein and microglia in Parkinson’s disease: Recent developments. Neuroscience 2015, 302, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Murrell, J.R.; Goedert, M.; Farlow, M.R.; Klug, A.; Ghetti, B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7737–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaliazka, K.; Kurouski, D. Nanoscale imaging of individual amyloid aggregates extracted from brains of Alzheimer and Parkinson patients reveals presence of lipids in α-synuclein but not in amyloid β1-42 fibrils. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, U.; Kayed, R. Amyloid β, Tau, and α-Synuclein aggregates in the pathogenesis, prognosis, and therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases. Prog. Neurobiol. 2022, 214, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, E.T.; Bhat, T.N.; Gulnik, S.; Hosur, M.V.; Sowder, R.C., 2nd; Cachau, R.E.; Collins, J.; Silva, A.M.; Erickson, J.W. Crystal structures of native and inhibited forms of human cathepsin D: Implications for lysosomal targeting and drug design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 6796–6800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlabicz, M.; Gacko, M.; Worowska, A.; Lapiński, R. Cathepsin E (EC 3.4.23.34)—A review. Folia. Histochem. Cytobiol. 2011, 49, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trezza, A.; Cicaloni, V.; Pettini, F.; Spiga, O. Chapter 2—Potential roles of protease inhibitors in anticancer therapy. In Cancer-Leading Proteases; Satya, P.G., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 13–49. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, J.; Hommel, U.; Cumin, F.; Martoglio, B.; Gerhartz, B. Aspartic proteases in drug discovery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

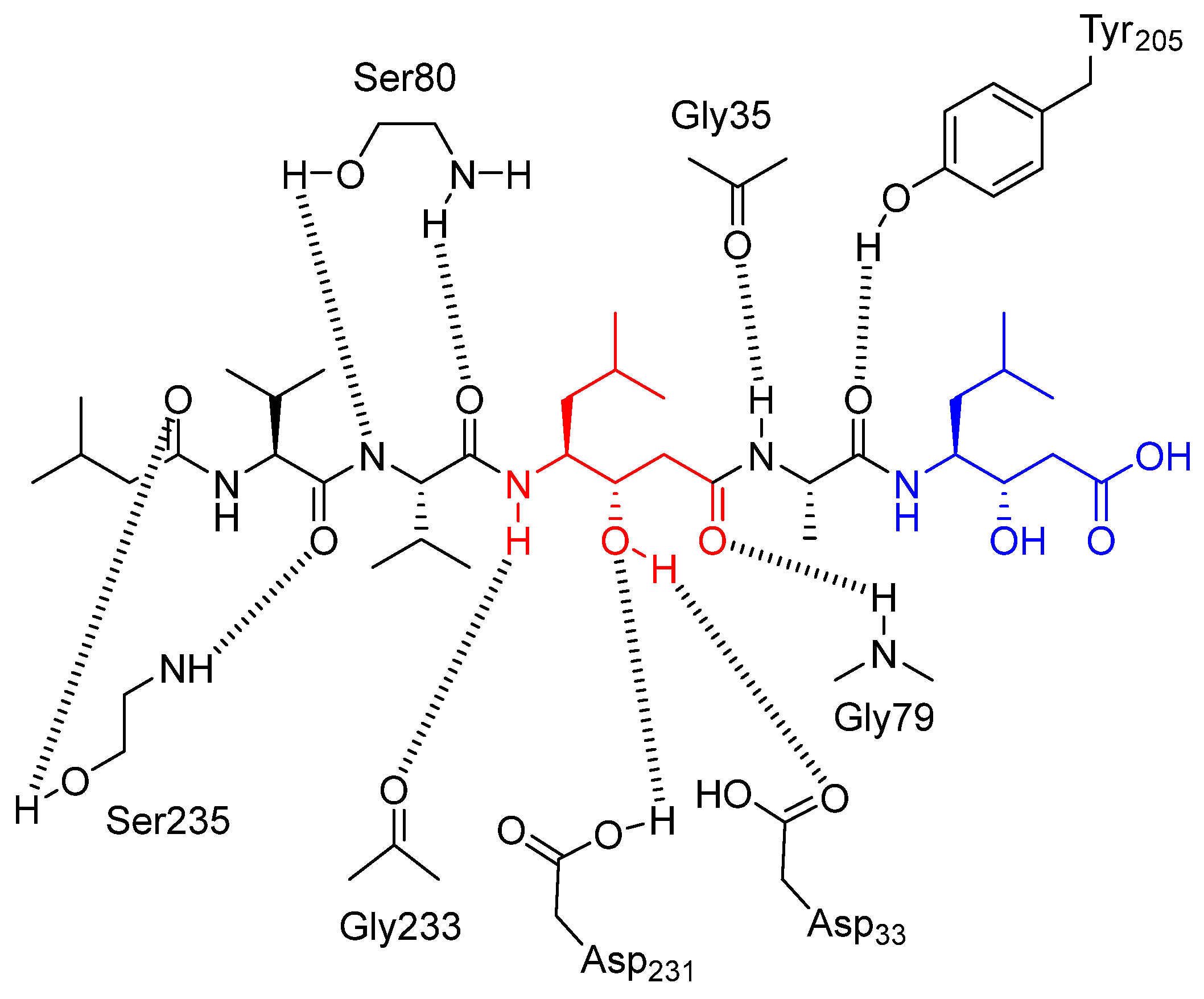

- Bailey, D.; Cooper, J.B.; Veerapandian, B.; Blundell, T.L.; Atrash, B.; Jones, D.M.; Szelke, M. X-ray-crystallographic studies of complexes of pepstatin A and a statine-containing human renin inhibitor with endothiapepsin. Biochem. J. 1993, 289, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

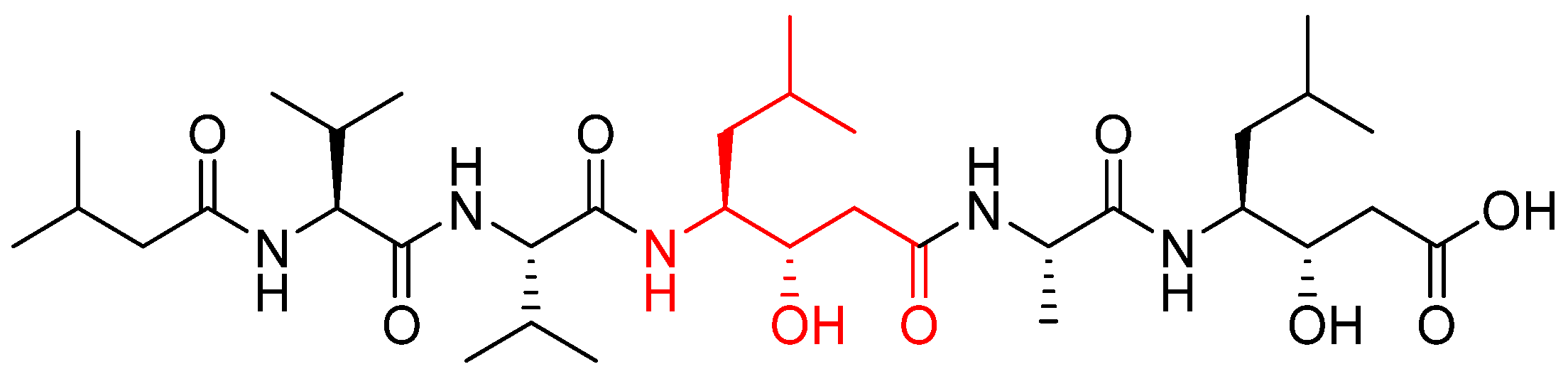

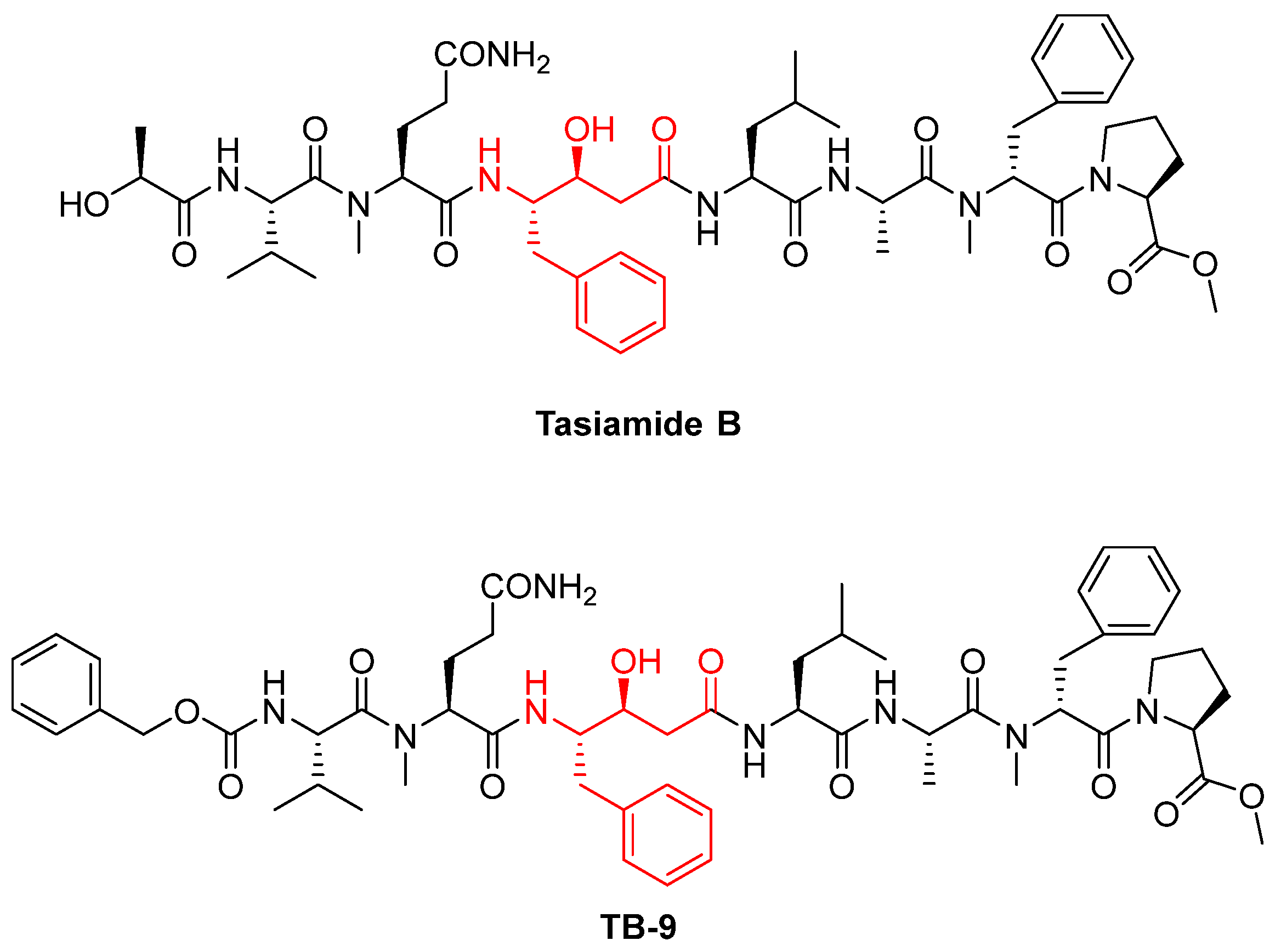

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Jiang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W. Cathepsin D inhibitors based on tasiamide B derivatives with cell membrane permeability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2022, 57, 116646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Bao, K.; Xu, H.; Wu, P.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W. Design, synthesis, and bioactivities of tasiamide B derivatives as cathepsin D inhibitors. J. Pept. Sci. 2019, 25, e3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenovic, M.; Fink, R.F.; Thiel, W.; Schirmeister, T.; Engels, B. On the origin of the stabilization of the zwitterionic resting state of cysteine proteases: A theoretical study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8696–8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, D.; Janjić, V.; Stern, I.; Podobnik, M.; Lamba, D.; Dahl, S.W.; Lauritzen, C.; Pedersen, J.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Structure of human dipeptidyl peptidase I (cathepsin C): Exclusion domain added to an endopeptidase framework creates the machine for activation of granular serine proteases. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 6570–6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaglia, T.; Vestuto, V.; Di Sarno, V.; Musella, S.; Smaldone, G.; Di Matteo, F.; Napolitano, V.; Miranda, M.R.; Pepe, G.; Basilicata, M.G.; et al. Peptidomimetics as potent dual SARS-CoV-2 cathepsin-L and main protease inhibitors: In silico design, synthesis and pharmacological characterization. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 266, 116128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.T.H.; Moesser, M.A.; Walters, R.K.; Malla, T.R.; Twidale, R.M.; John, T.; Deeks, H.M.; Johnston-Wood, T.; Mikhailov, V.; Sessions, R.B.; et al. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro peptide inhibitors from modelling substrate and ligand binding. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 13686–13703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsässer, B.; Zauner, F.B.; Messner, J.; Soh, W.T.; Dall, E.; Brandstetter, H. Distinct Roles of Catalytic Cysteine and Histidine in the Protease and Ligase Mechanisms of Human Legumain as Revealed by DFT-Based QM/MM Simulations. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5585–5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khara, A.; Jahangirian, E.; Tarrahimofrad, H. The Homology Modeling and Docking Investigation of Human Cathepsin B. Int. J. Med. Toxicol. Forensic Med. 2020, 10, 26687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votta, B.J.; Levy, M.A.; Badger, A.; Bradbeer, J.; Dodds, R.A.; James, I.E.; Thompson, S.; Bossard, M.J.; Carr, T.; Connor, J.R.; et al. Peptide aldehyde inhibitors of cathepsin K inhibit bone resorption both in vitro and in vivo. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997, 12, 1396–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesner, A.; Wysocka, M.; Solek, M.; Legowska, A.; Rolka, K. Low-molecular-weight aldehyde inhibitors of cathepsin G. Protein Pept. Lett. 2009, 16, 408–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, S.; Rahimova, R.; Sala, M.; Scala, M.C.; Vivenzio, G.; Musella, S.; Andrei, G.; Remans, K.; Mammri, L.; Snoeck, R.; et al. Rational design of the zonulin inhibitor AT1001 derivatives as potential anti SARS-CoV-2. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 244, 114857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, G.H.; Zhang, Y.N.; Zhang, Y.W.; Huang, P.; Ge, G.B. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro): Structure, function, and emerging therapies for COVID-19. MedComm (2020) 2022, 3, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpaderska, A.M.; Frankfater, A. An intracellular form of cathepsin B contributes to invasiveness in cancer. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 3493–3500. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Zang, X.; Vlahakis, N.W.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Ohashi, M.; Tang, Y. Enzymatic combinatorial synthesis of E-64 and related cysteine protease inhibitors. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 1783–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katunuma, N.; Murata, E.; Kakegawa, H.; Matsui, A.; Tsuzuki, H.; Tsuge, H.; Turk, D.; Turk, V.; Fukushima, M.; Tada, Y.; et al. Structure based development of novel specific inhibitors for cathepsin L and cathepsin S in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 1999, 458, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadaghiani, A.M.; Verhelst, S.H.; Gocheva, V.; Hill, K.; Majerova, E.; Stinson, S.; Joyce, J.A.; Bogyo, M. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of in vivo potency and selectivity of epoxysuccinyl-based inhibitors of papain-family cysteine proteases. Chem. Biol. 2007, 14, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Tomoo, K.; Matsugi, K.; Hara, T.; In, Y.; Murata, M.; Kitamura, K.; Ishida, T. Structural basis for development of cathepsin B-specific noncovalent-type inhibitor: Crystal structure of cathepsin B-E64c complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1597, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ménard, R.; Carrière, J.; Laflamme, P.; Plouffe, C.; Khouri, H.E.; Vernet, T.; Tessier, D.C.; Thomas, D.Y.; Storer, A.C. Contribution of the glutamine 19 side chain to transition-state stabilization in the oxyanion hole of papain. Biochemistry 1991, 30, 8924–8928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Gessel, M.M.; Wisniewski, M.L.; Viswanathan, K.; Wright, D.L.; Bahr, B.A.; Bowers, M.T. Z-Phe-Ala-diazomethylketone (PADK) disrupts and remodels early oligomer states of the Alzheimer disease Aβ42 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 6084–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, R.T.; Sivaraman, J. Structural basis for reversible and irreversible inhibition of human cathepsin L by their respective dipeptidyl glyoxal and diazomethylketone inhibitors. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 173, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöyhönen, S.; Er, S.; Domanskyi, A.; Airavaara, M. Effects of Neurotrophic Factors in Glial Cells in the Central Nervous System: Expression and Properties in Neurodegeneration and Injury. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: The roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobny, A.; Prieto Huarcaya, S.; Dobert, J.; Kluge, A.; Bunk, J.; Schlothauer, T.; Zunke, F. The role of lysosomal cathepsins in neurodegeneration: Mechanistic insights, diagnostic potential and therapeutic approaches. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2022, 1869, 119243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Crowther, R.A.; Jakes, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Goedert, M. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson’s disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6469–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, T.; Paciotti, S.; Chiasserini, D.; Calabresi, P.; Parnetti, L.; Beccari, T.; van de Berg, W.D. Lysosomal Dysfunction and α-Synuclein Aggregation in Parkinson’s Disease: Diagnostic Links. Mov. Disord. 2016, 31, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehay, B.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Caldwell, G.A.; Caldwell, K.A.; Yue, Z.; Cookson, M.R.; Klein, C.; Vila, M.; Bezard, E. Lysosomal impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednarczyk, J.; Lukasiuk, K. Tight junctions in neurological diseases. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2011, 71, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, V.; Stoka, V.; Vasiljeva, O.; Renko, M.; Sun, T.; Turk, B.; Turk, D. Cysteine cathepsins: From structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1824, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Hamamichi, S.; Caldwell, K.A.; Caldwell, G.A.; Yacoubian, T.A.; Wilson, S.; Xie, Z.L.; Speake, L.D.; Parks, R.; Crabtree, D.; et al. Lysosomal enzyme cathepsin D protects against alpha-synuclein aggregation and toxicity. Mol. Brain 2008, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, L.A.; Jansen, I.E.; van Rooij, J.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Kraaij, R.; Jankovic, J.; International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC); Heutink, P.; Shulman, J.M. Excessive burden of lysosomal storage disorder gene variants in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2017, 140, 3191–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlinchey, R.P.; Lee, J.C. Cysteine cathepsins are essential in lysosomal degradation of α-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 9322–9327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Niu, J.Y.; Xiong, J.; Nie, S.K.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, Z.H. LRRK2 G2019S Mutation Inhibits Degradation of α-Synuclein in an In Vitro Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Med. Sci. 2018, 38, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orenstein, S.J.; Kuo, S.H.; Tasset, I.; Arias, E.; Koga, H.; Fernandez-Carasa, I.; Cortes, E.; Honig, L.S.; Dauer, W.; Consiglio, A.; et al. Interplay of LRRK2 with chaperone-mediated autophagy. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, C.; Yin, N.; Gu, H.Y.; Zhu, J.L.; Ding, J.H.; Lu, M.; Hu, G. Atp13a2 Deficiency Aggravates Astrocyte-Mediated Neuroinflammation via NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2016, 22, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pišlar, A.; Tratnjek, L.; Glavan, G.; Živin, M.; Kos, J. Upregulation of cysteine protease cathepsin X in the 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pišlar, A.H.; Zidar, N.; Kikelj, D.; Kos, J. Cathepsin X promotes 6-hydroxydopamine-induced apoptosis of PC12 and SH-SY5Y cells. Neuropharmacology 2014, 82, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, A.; Sabarwal, A.; Narayan Mishra, J.P.; Singh, R.P. Plumbagin induces ROS-mediated apoptosis and cell cycle arrest and inhibits EMT in human cervical carcinoma cells. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 32022–32037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, C.L.; de Albuquerque Wanderley Sales, V.; Gomes de Melo, C.; Ferreira da Silva, R.M.; Vicente Nishimura, R.H.; Rolim, L.A.; Rolim Neto, P.J. Beta-lapachone: Natural occurrence, physicochemical properties, biological activities, toxicity and synthesis. Phytochemistry 2021, 186, 112713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauwendraat, C.; Reed, X.; Krohn, L.; Heilbron, K.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Tan, M.; Gibbs, J.R.; Hernandez, D.G.; Kumaran, R.; Langston, R.; et al. Genetic modifiers of risk and age at onset in GBA associated Parkinson’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Brain 2020, 143, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querfurth, H.W.; LaFerla, F.M. Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. Amyloid precursor protein and endosomal-lysosomal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Inseparable partners in a multifactorial disease. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 2729–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, D.M.; Lee, J.H.; Kumar, A.; Lee, S.; Orenstein, S.J.; Nixon, R.A. Autophagy failure in Alzheimer’s disease and the role of defective lysosomal acidification. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 37, 1949–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, E.A.; Ehrhard, A.; Moniatte, M.; Guenet, C.; Tardif, C.; Tarnus, C.; Sorokine, O.; Heintzelmann, B.; Nay, C.; Remy, J.M.; et al. A possible role for cathepsins D, E, and B in the processing of beta-amyloid precursor protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 244, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mançano, A.S.F.; Pina, J.G.; Froes, B.R.; Sciani, J.M. Autophagy-lysosomal pathway impairment and cathepsin dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1490275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, V.Y.; Kindy, M.; Reinheckel, T.; Peters, C.; Hook, G. Genetic cathepsin B deficiency reduces beta-amyloid in transgenic mice expressing human wild-type amyloid precursor protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller-Steiner, S.; Zhou, Y.; Arai, H.; Roberson, E.D.; Sun, B.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, G.; Esposito, L.; Mucke, L.; et al. Antiamyloidogenic and neuroprotective functions of cathepsin B: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2006, 51, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, S.; Kosicek, M.; Mladenovic-Djordjevic, A.; Smiljanic, K.; Kanazir, S.; Hecimovic, S. Loss of Cathepsin B and L Leads to Lysosomal Dysfunction, NPC-Like Cholesterol Sequestration and Accumulation of the Key Alzheimer’s Proteins. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sun, B.; Zhou, Y.; Grubb, A.; Gan, L. Cathepsin B degrades amyloid-β in mice expressing wild-type human amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 39834–39841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhou, Y.; Halabisky, B.; Lo, I.; Cho, S.H.; Mueller-Steiner, S.; Devidze, N.; Wang, X.; Grubb, A.; Gan, L. Cystatin C-cathepsin B axis regulates amyloid beta levels and associated neuronal deficits in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 2008, 60, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

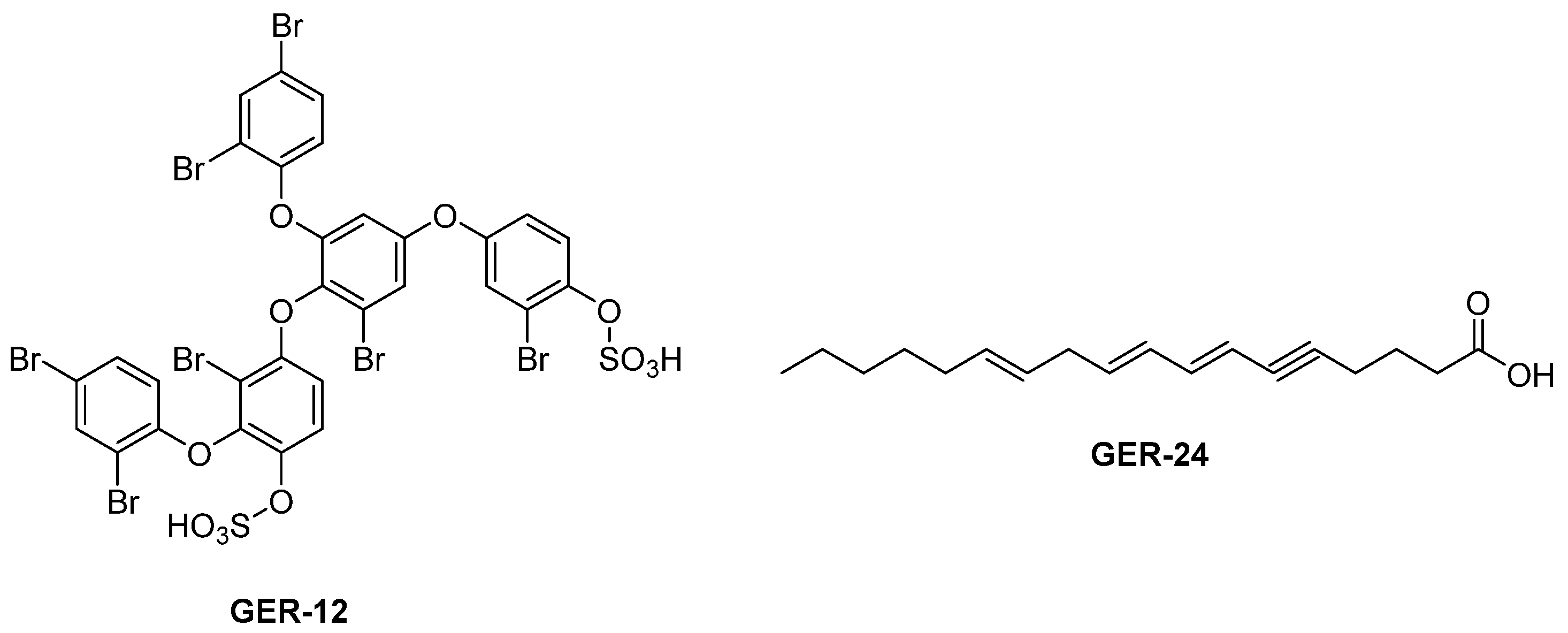

- Phan, V.V.; Mosier, C.; Yoon, M.C.; Glukhov, E.; Caffrey, C.R.; O’Donoghue, A.J.; Gerwick, W.H.; Hook, V. Discovery of pH-Selective Marine and Plant Natural Product Inhibitors of Cathepsin B Revealed by Screening at Acidic and Neutral pH Conditions. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 25346–25352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, W.; Zhu, X.R.; Lübbert, H.; Stichel, C.C. Differential expression of cathepsin X in aging and pathological central nervous system of mice. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 204, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, A.; Glavan, G.; Obermajer, N.; Živin, M.; Schliebs, R.; Kos, J. Neuroprotective role of γ-enolase in microglia in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease is regulated by cathepsin X. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, C.; Ilkjær, L.; Kempf, S.J.; Hemdrup, A.L.; von Linstow, C.U.; Babcock, A.A.; Darvesh, S.; Larsen, M.R.; Finsen, B. Diverse Protein Profiles in CNS Myeloid Cells and CNS Tissue From Lipopolysaccharide- and Vehicle-Injected APPSWE/PS1ΔE9 Transgenic Mice Implicate Cathepsin Z in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2018, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Y.; Gibbons, L.; Pritchard, A.; Hardicre, J.; Wren, J.; Tian, J.; Shi, J.; Stopford, C.; Julien, C.; Thompson, J.; et al. Genetic associations between cathepsin D exon 2 C-->T polymorphism and Alzheimer’s disease, and pathological correlations with genotype. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemenschneider, M.; Blennow, K.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Andreasen, N.; Prince, J.A.; Laws, S.M.; Förstl, H.; Kurz, A. The cathepsin D rs17571 polymorphism: Effects on CSF tau concentrations in Alzheimer disease. Hum. Mutat. 2006, 27, 532–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallwitz, L.; Schmidt, L.; Marques, A.R.A.; Tholey, A.; Cassidy, L.; Ulku, I.; Multhaup, G.; Di Spiezio, A.; Saftig, P. Cathepsin D: Analysis of its potential role as an amyloid beta degrading protease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 175, 105919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Yang, B.; Yu, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Q. Cathepsin B links oxidative stress to the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 362, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum-Degen, D.; Müller, T.; Kuhn, W.; Gerlach, M.; Przuntek, H.; Riederer, P. Interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6 are elevated in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s and de novo Parkinson’s disease patients. Neurosci. Lett. 1995, 202, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, S.M.; Tyrrell, P.J.; Rothwell, N.J. Interleukin-1 and neuronal injury. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.A.; Tabrizi, S.J. Huntington’s disease: From molecular pathogenesis to clinical treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, G.P.; Dorsey, R.; Gusella, J.F.; Hayden, M.R.; Kay, C.; Leavitt, B.R.; Nance, M.; Ross, C.A.; Scahill, R.I.; Wetzel, R.; et al. Huntington disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tydlacka, S.; Wang, C.E.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Li, X.J. Differential activities of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurons versus glia may account for the preferential accumulation of misfolded proteins in neurons. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 13285–13295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantle, D.; Falkous, G.; Ishiura, S.; Perry, R.H.; Perry, E.K. Comparison of cathepsin protease activities in brain tissue from normal cases and cases with Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 131, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.H.; Wang, Y.; Kegel, K.B.; Kazantsev, A.; Apostol, B.L.; Thompson, L.M.; Yoder, J.; Aronin, N.; DiFiglia, M. Autophagy regulates the processing of amino terminal huntingtin fragments. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 3231–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestroni, A.; Faull, R.L.; Strand, A.D.; Möller, T. Distinct neuroinflammatory profile in post-mortem human Huntington’s disease. Neuroreport 2009, 20, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutani, N.; Piccirillo, R.; Hourez, R.; Venkatraman, P.; Goldberg, A.L. Cathepsins L and Z are critical in degrading polyglutamine-containing proteins within lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 17471–17482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestler, E.J.; Barrot, M.; DiLeone, R.J.; Eisch, A.J.; Gold, S.J.; Monteggia, L.M. Neurobiology of depression. Neuron 2002, 34, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insel, T.R.; Wang, P.S. Rethinking mental illness. JAMA 2010, 303, 1970–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The role of inflammation in depression: From evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, C.; Matosin, N.; Kaul, D.; Philipsen, A.; Gassen, N.C. The Role of Cathepsins in Memory Functions and the Pathophysiology of Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czibere, L.; Baur, L.A.; Wittmann, A.; Gemmeke, K.; Steiner, A.; Weber, P.; Pütz, B.; Ahmad, N.; Bunck, M.; Graf, C.; et al. Profiling trait anxiety: Transcriptome analysis reveals cathepsin B (Ctsb) as a novel candidate gene for emotionality in mice. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanaeva, S.Y.; Rogozhnikova, A.A.; Alperina, E.L.; Gevorgyan, M.M.; Idov, G.V. Changes in Activity of Cysteine Cathepsins B and L in Brain Structures of Mice with Aggressive and Depressive-Like Behavior Formed under Conditions of Social Stress. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 164, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Ma, J. Cathepsin C Aggravates Neuroinflammation Involved in Disturbances of Behaviour and Neurochemistry in Acute and Chronic Stress-Induced Murine Model of Depression. Neurochem. Res. 2018, 43, 89–100, Erratum in: Neurochem. Res. 2018, 43, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, G.; Shimizu, T.; Ikenaka, K.; Fan, K.; Ma, J. Cathepsin C promotes microglia M1 polarization and aggravates neuroinflammation via activation of Ca2+-dependent PKC/p38MAPK/NF-κB pathway. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, M.; Höger, N.; Feige, B.; Blechert, J.; Normann, C.; Nissen, C. Fear extinction as a model for synaptic plasticity in major depressive disorder. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Okamoto, K.; Iwamoto, T.; Sakai, E.; Kanaoka, K.; Hu, J.P.; Shibata, M.; Hotokezaka, H.; Nishishita, K.; Mizuno, A.; et al. Pepstatin A, an aspartic proteinase inhibitor, suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. J. Biochem. 2006, 139, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, T.; Takauchi, S.; Ohara, K.; Kokai, M.; Nishii, R.; Maeda, S.; Takanaga, A.; Tanaka, T.; Takeda, M.; Seki, M.; et al. Alpha-synuclein-positive structures induced in leupeptin-infused rats. Brain. Res. 2005, 1040, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katunuma, N. Structure-based development of specific inhibitors for individual cathepsins and their medical applications. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2011, 87, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enzyme | Substrate | Associated Disease | Role in Neurodegeneration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTSD | APP, Tau, Aβ | AD | Contributes to neurodegeneration by impairing lysosomal acidification, disrupting proteostasis, and promoting the accumulation of misfolded proteins, leading to enhanced neuroinflammatory and degenerative processes | [34] |

| αSyn | PD, MSA, DLB | [35] | ||

| HTT | HD | [36] | ||

| PrP | Prion disease | [37] | ||

| ApoE | AD | [38] | ||

| CTSB | APP, Aβ | AD | NF-κB activation, mitochondrial transcription factor A degradation, induction of apoptosis via pro-caspase-1/11 activation, and contribution to neurotoxic Aβ production. Also amplifies microglial-driven inflammation and ROS/RNS release. | [34] |

| αSyn | PD, MSA, DLB | [39] | ||

| Htt | HD | [36] | ||

| PrP | Prion disease | [37] | ||

| CTSL | APP | AD | Facilitates neuroinflammation via activation of caspase-8 and NF-κB pathways, enhances expression of iNOS/COX-2. | [38] |

| αSyn | PD, MSA, DLB | [35,39,40] | ||

| Htt | HD | [41] | ||

| PrP | Prion disease | [37] | ||

| CTSS | APP, Aβ | AD | Remains active at neutral pH, enabling extracellular matrix degradation and microglial migration. | [42] |

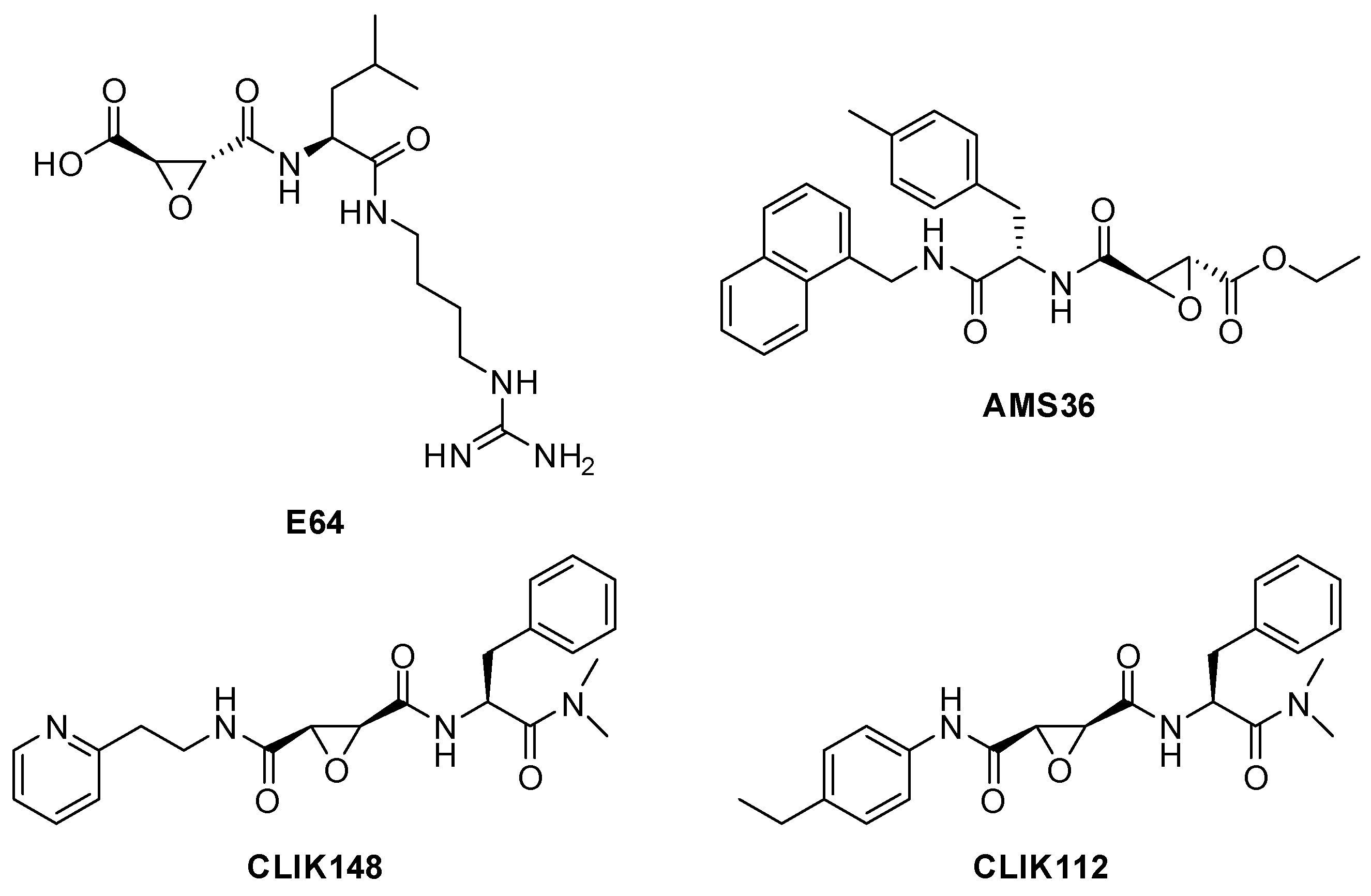

| Modulator/Inhibitor | Class/Functional Group | Target Cathepsin(s) | Mechanism | Uses and References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

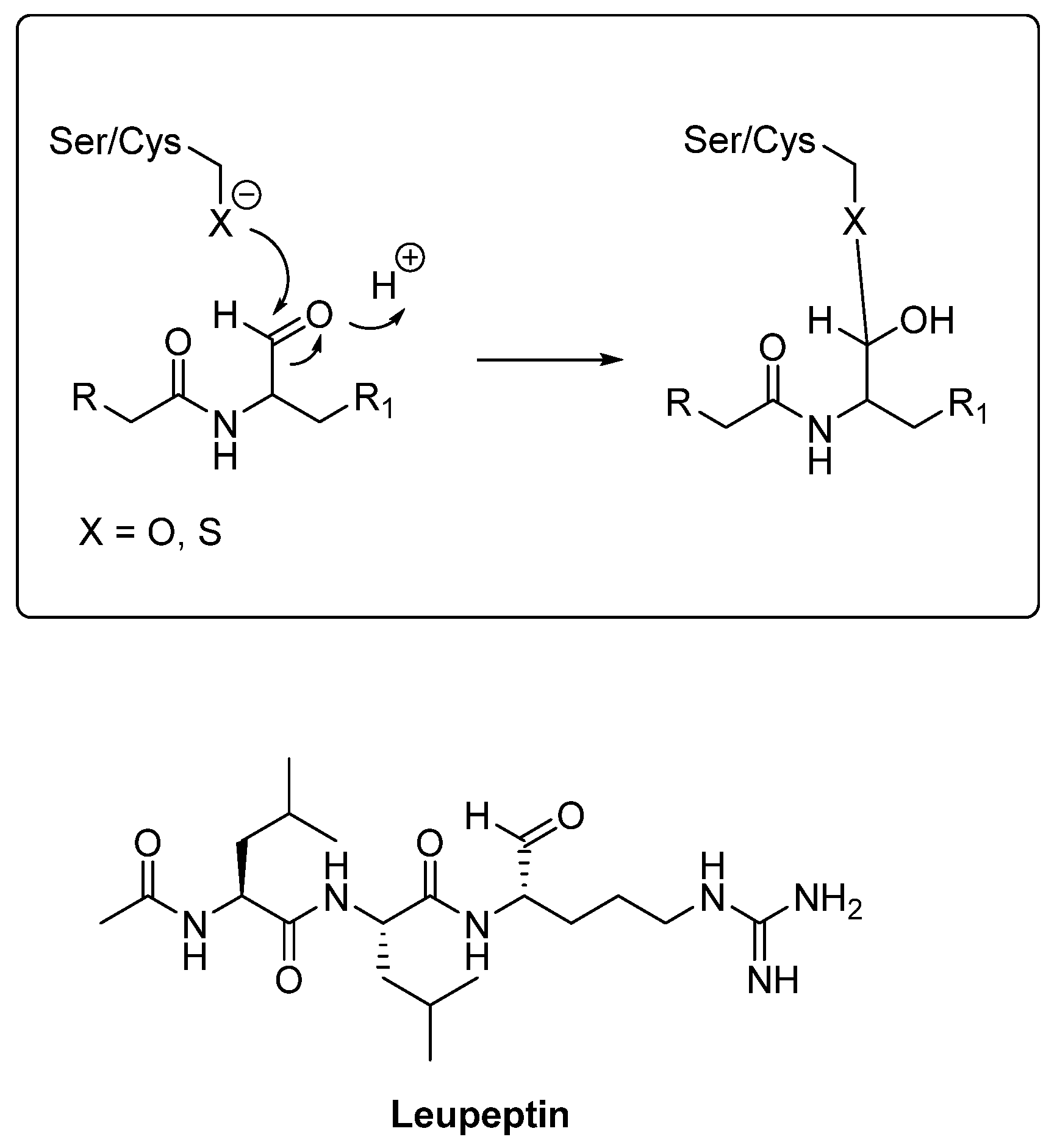

| Pepstatin A | Synthetic peptide, hydroxyethylamine group | CTSD | It acts as a competitive and reversible inhibitor that binds to the active site of aspartyl proteases, blocking their function. It achieves this by mimicking the transition state of the substrate [66]. | Classical inhibitor of aspartic proteases; frequently used in autophagy studies [144]. |

| Tasiamide B | Natural peptide, hydroxyethylamine group | CTSD | It acts as a competitive inhibitor, mimicking the tetrahedral intermediate of the enzyme [68]. | Hit compound to develop other aspartic inhibitors [67]. |

| TB-9 | Synthetic peptide, derivative of tasiamide B | CTSD CTSE | Same mechanism of inhibition of Tasiamide B [67]. | Under investigation to improve cell permeability [67,68]. |

| Leupeptin | Peptide aldehyde | CTSA, B, D Reversible inhibitor | It acts as a competitive inhibitor that forms a reversible, covalent hemiacetal bond between its aldehyde group and the enzyme’s active site [69]. | Under investigation for Parkinson’s disease [145]. |

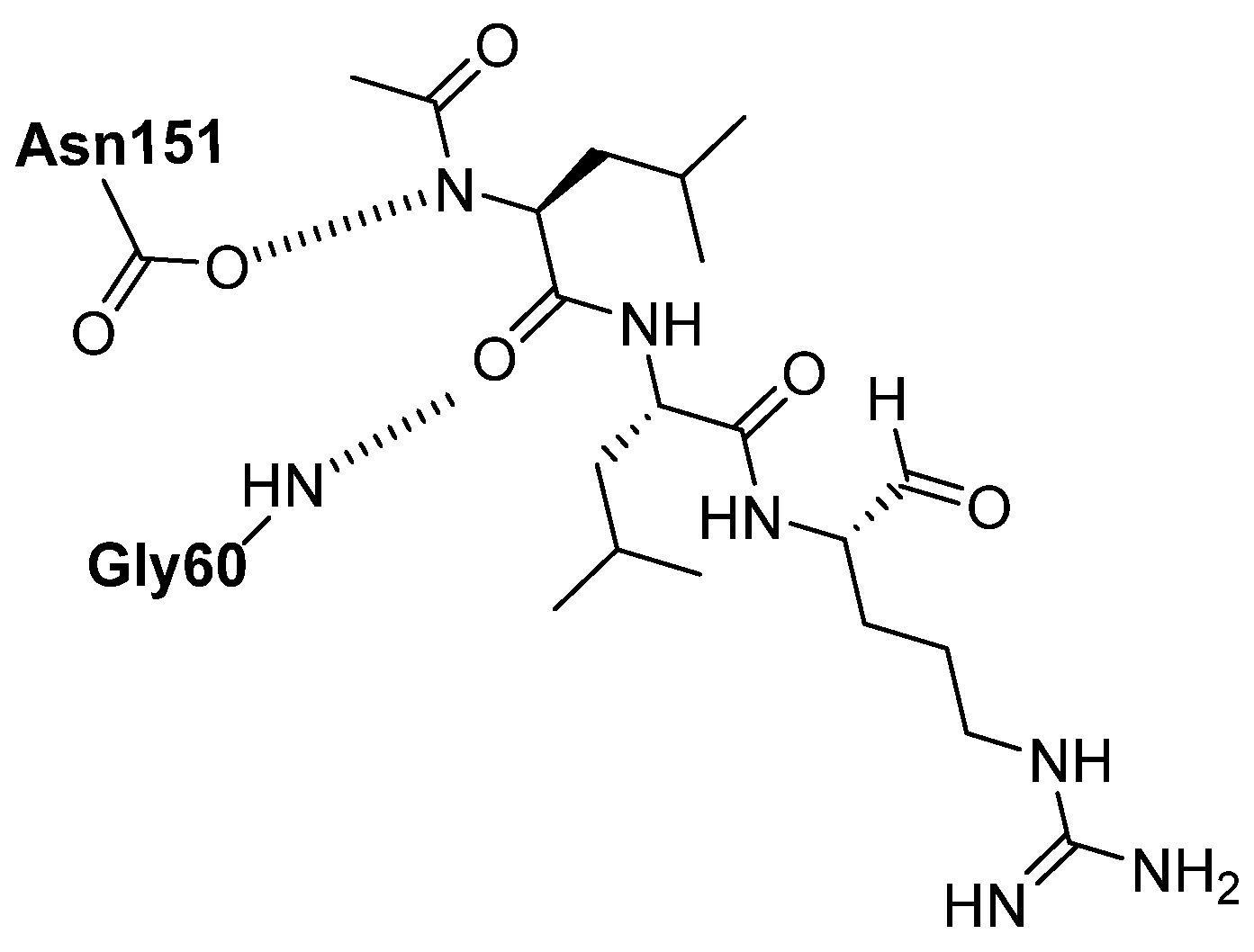

| Cbz-Leu-Leu-Leu-H Ac-Phe-Val-Thr-Gnf-CHO Octanoyl-Gly-Phe-His-CHO | Peptide aldehyde | CTSK, CTSG Mpro | Same mechanism as leupeptin [74]. | Under investigations [75,76,77]. |

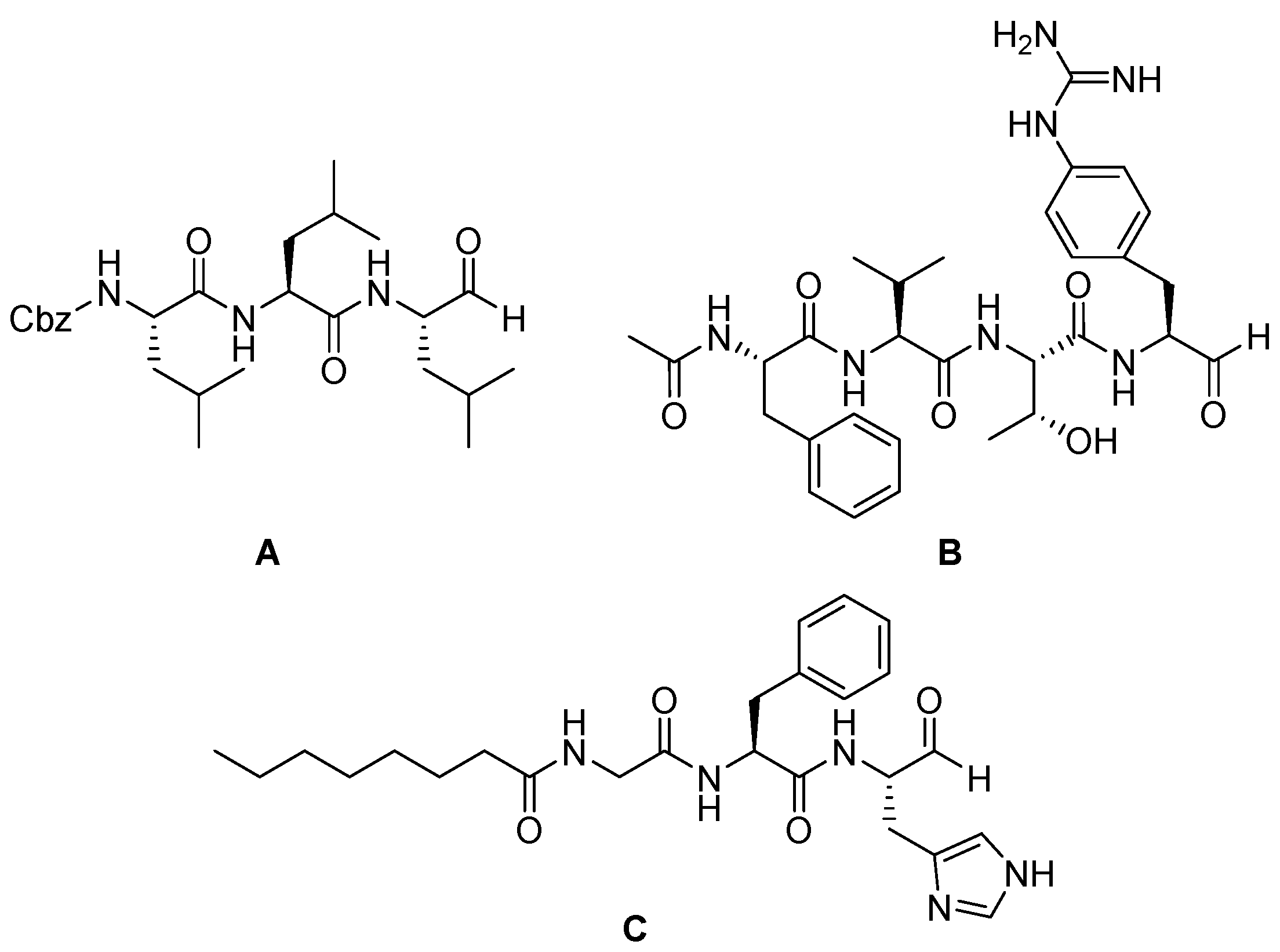

| E-64 | Epoxysuccinate (natural origin) | CTSB, CTSL, CTSK, CTSH, CTSS Irreversible inhibitor | The epoxide group forms a covalent bond, inactivating the enzyme [80]. | Widely used in research [79,80]. |

| E-64d (Aloxistatin) | epoxysuccinate | CTSB, CTSL (+calpain) Irreversible inhibitor | Same mechanism as E-64 [80]. | Cell-permeable derivative of E-64; used in models of Alzheimer’s and traumatic injury [83]. |

| AMS36 | epoxysuccinate | Irreversible inhibitor of CTSX | Same mechanism as E-64 [80]. | Under investigation for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease [103]. |

| CA-074 methyl ester | epoxysuccinate | Irreversible inhibitor of CTSB | Same mechanism as E-64 [80]. | Under investigation in Alzheimer’s disease [114]. |

| CLIK-148 | epoxysuccinate | CTSL | Same mechanism as E-64 [80]. | Synthetic analogues of E64, several potential medical applications [146]. |

| Z-FY(t-Bu)-DMK | diazomethylketone | CTSL | It acts as irreversible inhibitor of the enzyme [86]. | Mainly used in research [85]. |

| PADK | diazomethylketone | CTSB, CTSL | Same mechanism as Z-FY(t-Bu)-DMK [86]. | Inhibits CTSB/CTSL; prevents BACE1 and APP-CTF degradation in cells [85]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Matteo, F.; Vietri, M.; D’Alessio, S.; Ciaglia, T.; Vestuto, E.F.; Pepe, G.; Moltedo, O.; Di Sarno, V.; Musella, S.; Ostacolo, C.; et al. Targeting Cathepsins in Neurodegeneration: Biochemical Advances. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123019

Di Matteo F, Vietri M, D’Alessio S, Ciaglia T, Vestuto EF, Pepe G, Moltedo O, Di Sarno V, Musella S, Ostacolo C, et al. Targeting Cathepsins in Neurodegeneration: Biochemical Advances. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123019

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Matteo, Francesca, Mariapia Vietri, Simone D’Alessio, Tania Ciaglia, Erica Federica Vestuto, Giacomo Pepe, Ornella Moltedo, Veronica Di Sarno, Simona Musella, Carmine Ostacolo, and et al. 2025. "Targeting Cathepsins in Neurodegeneration: Biochemical Advances" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123019

APA StyleDi Matteo, F., Vietri, M., D’Alessio, S., Ciaglia, T., Vestuto, E. F., Pepe, G., Moltedo, O., Di Sarno, V., Musella, S., Ostacolo, C., Cominelli, F., Campiglia, P., Bertamino, A., Miranda, M. R., & Vestuto, V. (2025). Targeting Cathepsins in Neurodegeneration: Biochemical Advances. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3019. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123019