Post-Translational Modifications: Key “Regulators” of Pancreatic Cancer Malignant Phenotype—Advances in Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies

Abstract

1. Introduction

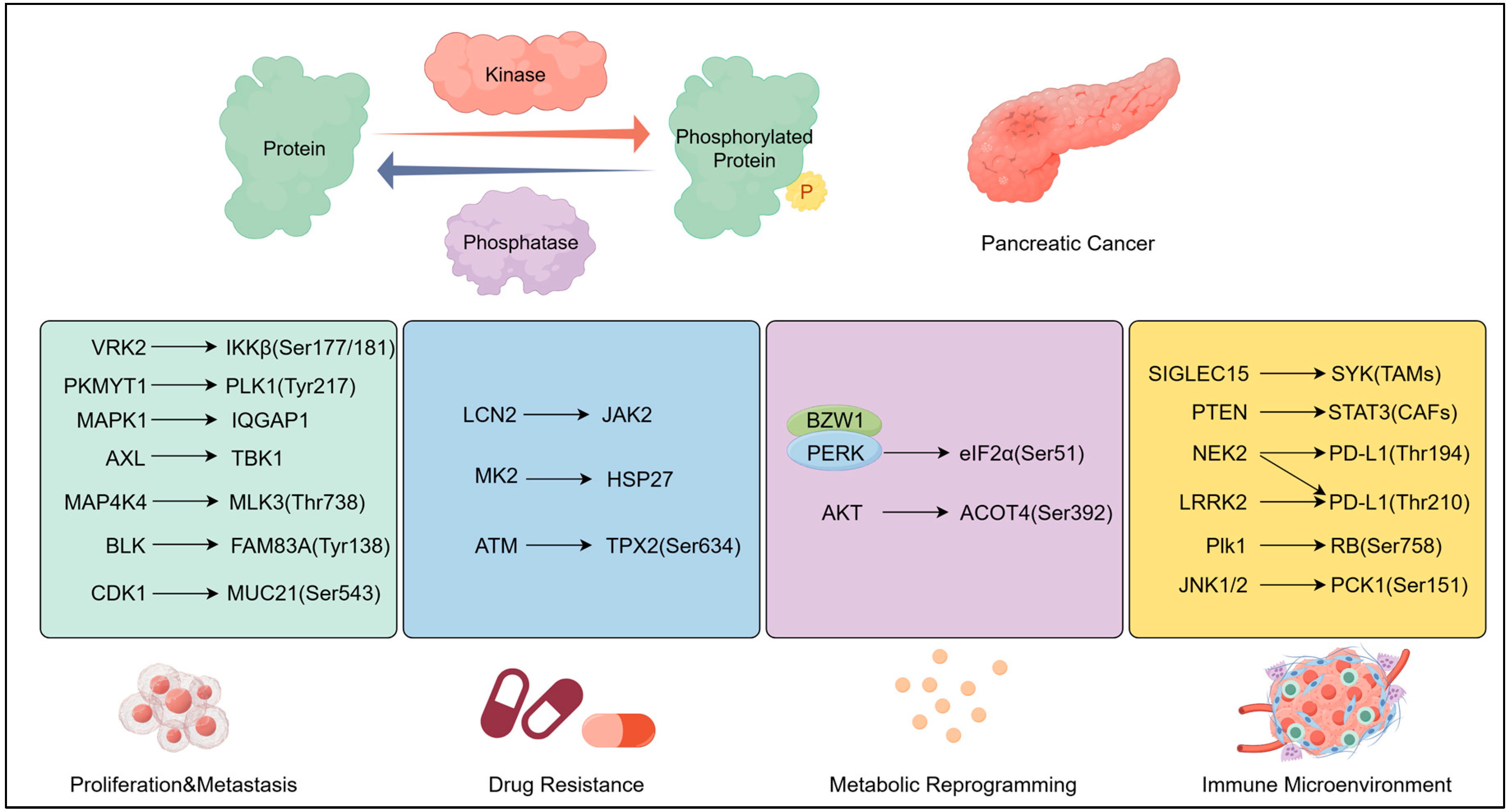

2. Phosphorylation: Regulatory Foundation of Oncogenic Signalling

2.1. Mechanisms: Core Regulation by Kinases/Phosphatases

2.1.1. KRAS-ERK: The “Master Switch” of Phosphorylation-Dependent Oncogenesis

2.1.2. STAT3 Dual-Site Phosphorylation: Integration of Inflammation and Proliferation

2.1.3. Other Kinase–Phosphatase Axes

2.2. Pathological Regulation by Phosphorylation

2.2.1. Proliferation and Metastasis by Phosphorylation

2.2.2. Drug Resistance by Phosphorylation

2.2.3. Metabolic Reprogramming by Phosphorylation

2.2.4. Immune Microenvironment Regulation

2.3. Targeted Therapy: Inhibitors of KRAS, STAT3, and Other Phosphorylation Targets

2.3.1. KRAS Inhibitors

2.3.2. STAT3 Inhibitors

2.3.3. Other Phosphorylation Targets

| Drug Name | Target Molecule | Pathway | Efficacy | PDAC Models | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRTX1133 | KRAS G12D | KRAS pathway | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth | subcutaneous model | [72] |

| KS-58 | KRAS G12D | KRAS/ERK pathway | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth | subcutaneous/ orthotopic tumor model | [84,85] |

| ADT-1004 | Pan-RAS (G12D/G12V/G12C) | Ras pathway; KRAS/ERK pathway | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth | PDX | [33] |

| Triptolide | STAT3 (Tyr705) | STAT3 pathway | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth | subcutaneous model | [90] |

| WB436B | STAT3 (SH2 domain) | STAT3 pathway | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis | subcutaneous model | [91] |

| Compound 4C | STAT3 (SH2 domain) | STAT3 pathway | Inhibits both STAT3 nuclear transcription and mitochondrial OXPHOS; Potent antitumor efficacy | subcutaneous model | [92] |

| YY002 | STAT3 (SH2 domain) | STAT3 pathway | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis; | subcutaneous model | [43] |

| quinoxaline urea analog 84 | IKKβ (Ser177/Ser181) | TNFα-NF-κB pathway | Both single-drug and combination chemotherapy can inhibit the progression of pancreatic cancer | subcutaneous model | [93] |

| C66 | JNK | JNK pathway; Inflammatory cytokines | Disrupt the inflammatory microenvironment; Suppress tumour proliferation and migration | cell model | [94] |

| PF-3758309 | AMPK | Ferroptosis | Sensitize pancreatic cancer cells to ferroptosis induction | PDO | [95] |

| GNE-495 | MAP4K4 | MAP4K4 pathway | Inhibit the proliferation and induce apoptosis; Reduce tumour stromal formation | KPC mouse model | [52] |

| F389-0746 | MAP4K4 | MAP4K4 pathway | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth | subcutaneous model | [96] |

| Compound 150441 | CLK4 | CLK4-mediated spliceosome phosphorylation | Inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth and survival | cell model | [97] |

| AT7519 | CDK | Cell cycle; Transcriptional control | Block cell cycle and transcription process; Inhibit tumour growth | PDX and PDO | [98] |

| zinc pyrithione (ZnPT) | SDCBP | YAP1 phosphorylation | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth | PDX and PDO | [99] |

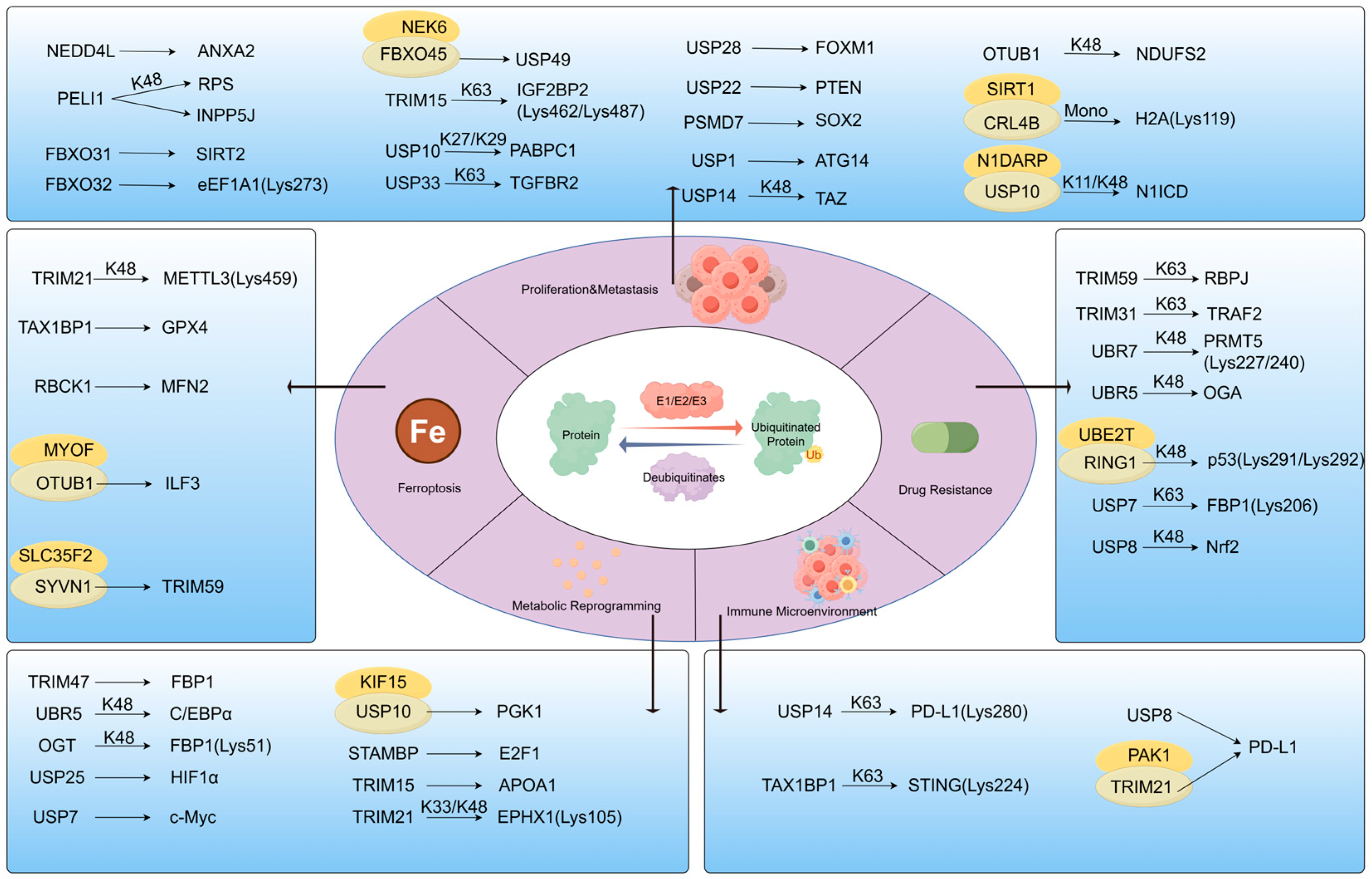

3. Ubiquitination: Regulator of Protein Homeostasis and Network Balance

3.1. Mechanisms: Specific Regulation of E3 Ligase/Deubiquitinase

3.2. Pathological Regulation by Ubiquitination

3.2.1. Proliferation and Metastasis by Ubiquitination

3.2.2. Ferroptosis

3.2.3. Drug Resistance by Ubiquitination

3.2.4. Metabolic Reprogramming by Ubiquitination

3.2.5. Immune Microenvironment Remodelling

3.3. Ubiquitination-Targeted Inhibitors: Applications and Research

| Drug Name | Target Molecule | Pathway | Efficacy | PDAC Models | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N6F11 | TRIM25 | Ferroptosis; Anti-tumour immunity | Trigger ferroptosis in tumour; Activate antitumour immunity | KPC and orthotopic tumor model | [152] |

| PGG | UBE2T | Ubiquitination-dependent degradation of p53 | Enhance the therapeutic sensitivity to gemcitabine; Inhibition of tumour growth | PDX and KPC | [136] |

| Taraxasterol (TAX) | MDM2 | Promoting nuclear translocation of p53 | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth | subcutaneous model | [153] |

| DHPO | UbcH5c | IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation | Inhibit pancreatic cancer growth and metastasis | orthotopic tumor model | [154] |

| DUB-IN-2 | USP8 | Anti-tumour immunity | Enhance the antitumor effect of PD-L1 antibodies | subcutaneous model | [149] |

| I-138 | USP1 | Autophagy | Inhibit PDAC progression and enhances cisplatin efficacy | subcutaneous model | [117] |

| P5091 | USP7 | glycolysis | Inhibit pancreatic cancer progression | KPC and subcutaneous model | [143] |

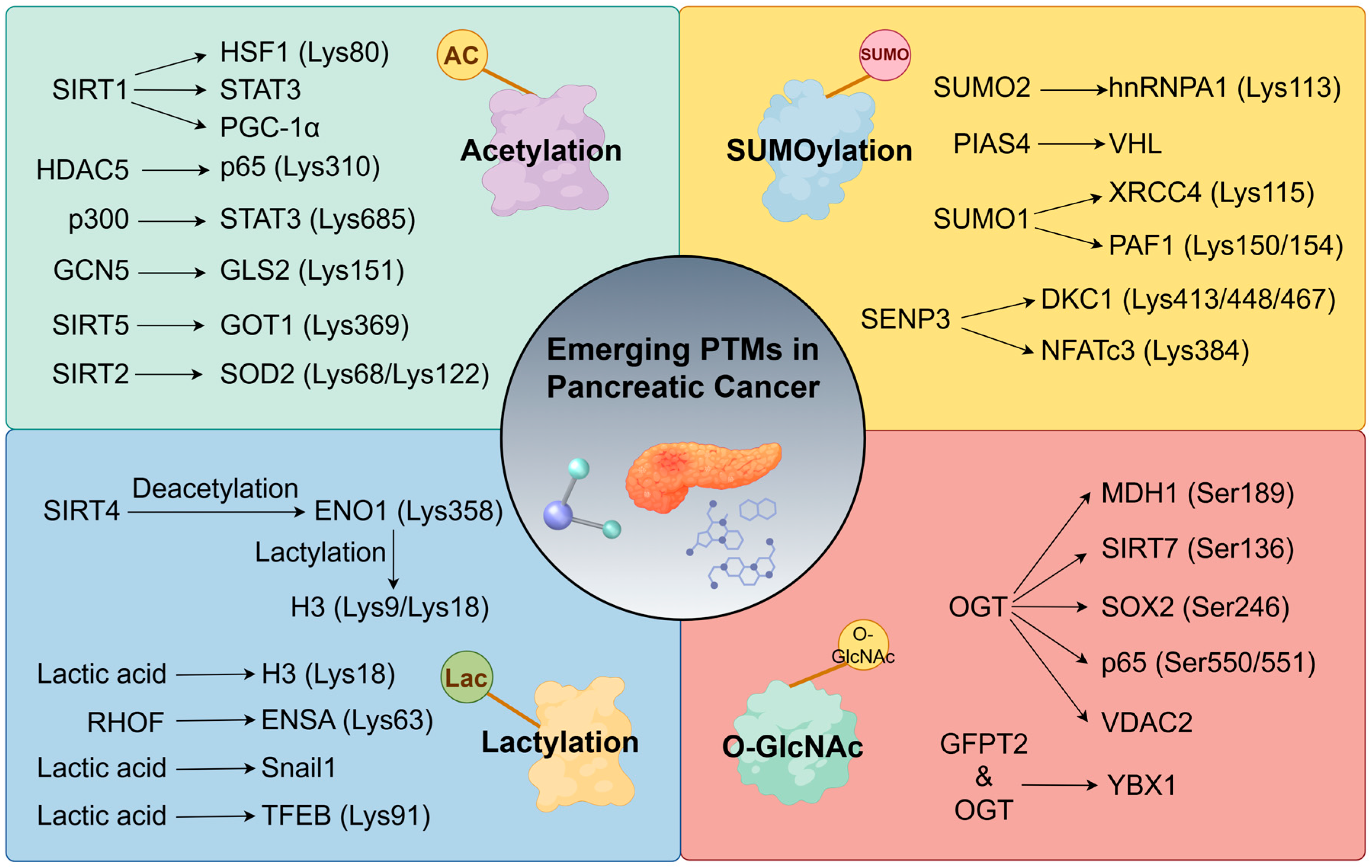

4. Emerging PTMs as Network Extensions

4.1. Acetylation: A Regulator of Immune Microenvironment/Metabolism

4.1.1. Immune Microenvironment Regulation

4.1.2. Metabolic Reprogramming

4.1.3. Acetylation Target Therapy

4.2. SUMOylation

4.3. Lactylation

4.4. O-GlcNAcylation

| Drug Name | Target Molecule | Pathway | Efficacy | PDAC Models | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fisetin | CDK1 | Stem cell properties | Enhance gemcitabine sensitivity | KPC; subcutaneous model | [167] |

| Fisetin | SIRT2 | Oxidative stress and proliferation-apoptosis | Inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis | subcutaneous model | [168] |

| C646 | histone H3 | Cell cycle | Inhibit tumour growth; Enhance antitumour efficacy | subcutaneous model | [169] |

| pyrrole-pyridine-imidazole derivative 8a | SIRT6 | Apoptosis; DNA damage repair | Inhibit proliferation; Promote apoptosis; Reverse resistance to gemcitabine. | subcutaneous model | [170] |

| Givinostat; Dacinostat | HDAC | Anti-tumour immunity | Enhance the CTL-mediated killing | cell model | [171] |

| ISOX | HDAC6 | Stem cell properties | Inhibit tumour growth and metastasis; Enhance the antitumor effect of 5-FU | tumor organoid model; orthotopic model | [172] |

| TAK-981 | SUMO ligase E1 | Cell cycle; Interferon signalling pathway | Impedes tumour progression; Enhance antitumour immune responses | subcutaneous model | [181] |

| ML-792; ML-93 | SUMO ligase | Cell cycle; Apoptosis | Inhibit tumour growth and induce apoptosis | tumor organoid model; subcutaneous model | [184] |

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTMs | Post-translational modifications |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| PNI | Perineural invasion |

| DSB | DNA double-strand break |

| TAMs | Tumour-associated macrophages |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| TME | Tumour microenvironment |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| PDX | Patient-derived xenografts |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| UPS | Ubiquitin-proteasome system |

| USP | Ubiquitin-specific protease |

| UCH | Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase |

| OTU | Ovarian tumour protease |

| DUBs | Deubiquitinating enzymes |

| HAT | Histone acetyltransferase |

| SAE | SUMO ligase |

| Kla | Lactylation |

| pCAFs | Perineuronal infiltration-associated cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| OGTs | O-GlcNAcyltransferases |

| OGAs | O-GlcNAc hydrolases |

| IMS | Imaging mass spectrometry |

| DIA | Data-independent acquisition |

| ICBs | Immune checkpoint blockers |

| PDO | Patient-derived organoids |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: Globocan Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahib, L.; Wehner, M.R.; Matrisian, L.M.; Nead, K.T. Estimated Projection of Us Cancer Incidence and Death to 2040. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e214708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torphy, R.J.; Fujiwara, Y.; Schulick, R.D. Pancreatic Cancer Treatment: Better, but a Long Way to Go. Surg. Today 2020, 50, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbrook, C.J.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Pasca di Magliano, M.; Maitra, A. Pancreatic Cancer: Advances and Challenges. Cell 2023, 186, 1729–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groot, V.P.; Rezaee, N.; Wu, W.; Cameron, J.L.; Fishman, E.K.; Hruban, R.H.; Weiss, M.J.; Zheng, L.; Wolfgang, C.L.; He, J. Patterns, Timing, and Predictors of Recurrence Following Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamisawa, T.; Wood, L.D.; Itoi, T.; Takaori, K. Pancreatic Cancer. Lancet 2016, 388, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.H.; Byrne, K.T.; Vonderheide, R.H. Immunotherapy and Prevention of Pancreatic Cancer. Trends Cancer 2018, 4, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, A.S.; Vonderheide, R.H.; O’Hara, M.H. Challenges and Opportunities for Pancreatic Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 788–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, D. Parp and Parg Inhibitors in Cancer Treatment. Genes. Dev. 2020, 34, 360–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.P. Pancreatic Cancer Epidemiology: Understanding the Role of Lifestyle and Inherited Risk Factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuigan, A.; Kelly, P.; Turkington, R.C.; Jones, C.; Coleman, H.G.; McCain, R.S. Pancreatic Cancer: A Review of Clinical Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Treatment and Outcomes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 4846–4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hank, T.; Klaiber, U.; Hinz, U.; Schutte, D.; Leonhardt, C.S.; Bergmann, F.; Hackert, T.; Jager, D.; Buchler, M.W.; Strobel, O. Oncological Outcome of Conversion Surgery after Preoperative Chemotherapy for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Ann. Surg. 2023, 277, e1089–e1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Narang, A.; He, J.; Wolfgang, C.; Li, K.; Zheng, L. Consensus, Debate, and Prospective on Pancreatic Cancer Treatments. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.J.; Feng, Y.H.; Gu, B.H.; Li, Y.M.; Chen, H. The Post-Translational Modification, Sumoylation, and Cancer (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 52, 1081–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deribe, Y.L.; Pawson, T.; Dikic, I. Post-Translational Modifications in Signal Integration. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Qian, C.; Cao, X. Post-Translational Modification Control of Innate Immunity. Immunity 2016, 45, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licheva, M.; Raman, B.; Kraft, C.; Reggiori, F. Phosphoregulation of the Autophagy Machinery by Kinases and Phosphatases. Autophagy 2022, 18, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichla, M.; Sneyers, F.; Stopa, K.B.; Bultynck, G.; Kerkhofs, M. Dynamic Control of Mitochondria-Associated Membranes by Kinases and Phosphatases in Health and Disease. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6541–6556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, T. Protein Kinases and Phosphatases: The Yin and Yang of Protein Phosphorylation and Signaling. Cell 1995, 80, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antao, A.M.; Tyagi, A.; Kim, K.S.; Ramakrishna, S. Advances in Deubiquitinating Enzyme Inhibition and Applications in Cancer Therapeutics. Cancers 2020, 12, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komander, D.; Clague, M.J.; Urbe, S. Breaking the Chains: Structure and Function of the Deubiquitinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, H.; Nkwe, N.S.; Estavoyer, B.; Messmer, C.; Gushul-Leclaire, M.; Villot, R.; Uriarte, M.; Boulay, K.; Hlayhel, S.; Farhat, B.; et al. An Inventory of Crosstalk between Ubiquitination and Other Post-Translational Modifications in Orchestrating Cellular Processes. iScience 2023, 26, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Hwang, S.; Cha, J.Y.; Lee, H.J. Programmed Death Ligand 1 Regulatory Crosstalk with Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination: Implications in Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yan, Q.; Jiang, S.; Hu, D.; Lu, P.; Li, S.; Sandai, D.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, C. Protein Post-Translational Modifications and Tumor Immunity: A Pan-Cancer Perspective. Phys. Life Rev. 2025, 55, 142–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.H.; Krebs, E.G. Conversion of Phosphorylase B to Phosphorylase a in Muscle Extracts. J. Biol. Chem. 1955, 216, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, T.; Cooper, J.A. Protein-Tyrosine Kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985, 54, 897–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shindo, S.; Kakizaki, S.; Sakaki, T.; Kawasaki, Y.; Sakuma, T.; Negishi, M.; Shizu, R. Phosphorylation of Nuclear Receptors: Novelty and Therapeutic Implications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 248, 108477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Hong, F.; Yang, S. Protein Phosphorylation in Cancer: Role of Nitric Oxide Signaling Pathway. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, Q.; Dong, X.; Chen, M.; Han, T. Phosphorylation of Polysaccharides: A Review on the Synthesis and Bioactivities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 184, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandi, D.S.R.; Nagaraju, G.P.; Sarvesh, S.; Carstens, J.L.; Foote, J.B.; Graff, E.C.; Fang, Y.D.; Keeton, A.B.; Chen, X.; Valiyaveettil, J.; et al. Adt-1004: A First-in-Class, Oral Pan-Ras Inhibitor with Robust Antitumor Activity in Preclinical Models of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, P.; Chang, D.K.; Nones, K.; Johns, A.L.; Patch, A.M.; Gingras, M.C.; Miller, D.K.; Christ, A.N.; Bruxner, T.J.; Quinn, M.C.; et al. Genomic Analyses Identify Molecular Subtypes of Pancreatic Cancer. Nature 2016, 531, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, A.; Hong, J.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.A. The Pancreatic Cancer Genome Revisited. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrell, E.M.; Morrison, D.K. Ras-Mediated Activation of the Raf Family Kinases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2019, 9, a033746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomp, J.E.; Klomp, J.A.; Der, C.J. The Erk Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling Network: The Final Frontier in Ras Signal Transduction. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavoie, H.; Gagnon, J.; Therrien, M. Erk Signalling: A Master Regulator of Cell Behaviour, Life and Fate. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klomp, J.E.; Diehl, J.N.; Klomp, J.A.; Edwards, A.C.; Yang, R.; Morales, A.J.; Taylor, K.E.; Drizyte-Miller, K.; Bryant, K.L.; Schaefer, A.; et al. Determining the Erk-Regulated Phosphoproteome Driving Kras-Mutant Cancer. Science 2024, 384, eadk0850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Hu, Q.; Ji, S.; Xu, J.; Dai, W.; Liu, W.; Xu, W.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, Q.; et al. Homeodomain-Interacting Protein Kinase 2 Suppresses Proliferation and Aerobic Glycolysis Via Erk/Cmyc Axis in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Prolif. 2019, 52, e12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, S.; Fan, H.; Ji, D.; Chen, C.; Sheng, W. Gins2 Promotes Emt in Pancreatic Cancer Via Specifically Stimulating Erk/Mapk Signaling. Cancer Gene Ther. 2021, 28, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.H.; Hsu, T.W.; Chen, H.A.; Su, C.M.; Huang, M.T.; Chuang, T.H.; Su, J.L.; Hsieh, C.L.; Chiu, C.F. Erk-Mediated Transcriptional Activation of Dicer Is Involved in Gemcitabine Resistance of Pancreatic Cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 4420–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Bian, A.; Zhou, W.; Miao, Y.; Ye, J.; Li, J.; He, P.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Z.; et al. Discovery of the Highly Selective and Potent Stat3 Inhibitor for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Tao, J.; Man, S.; Zhang, N.; Ma, L.; Guo, L.; Huang, L.; Gao, W. Structure, Function, Signaling Pathways and Clinical Therapeutics: The Translational Potential of Stat3 as a Target for Cancer Therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Sun, H.; Li, Z.; Ge, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, T.; Gao, S.; et al. Bicc1 Drives Pancreatic Cancer Progression by Inducing Vegf-Independent Angiogenesis. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qiao, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, X.; Du, Q.; Deng, Y.; Cao, L. Vrk2 Activates Tnfalpha/Nf-Kappab Signaling by Phosphorylating Ikkbeta in Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 1288–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Xiong, Y.; Luo, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, F.; Lan, H.; Pang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.; et al. Genome-Wide Crispr Screens Identify Pkmyt1 as a Therapeutic Target in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. EMBO Mol. Med. 2024, 16, 1115–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, E.N.; Alzhanova, D.; Westcott, J.M.; Hinz, S.; Tiron, C.E.; Blo, M.; Mai, A.; Virtakoivu, R.; Phinney, N.; Nord, S.; et al. Axl-Tbk1 Driven Akt3 Activation Promotes Metastasis. Sci. Signal 2024, 17, eado6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhu, X.; Liu, N.; Dong, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Tang, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, M.; Wang, M.; et al. B-Lymphoid Tyrosine Kinase-Mediated Fam83a Phosphorylation Elevates Pancreatic Tumorigenesis through Interacting with Beta-Catenin. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.W.; Jin, X.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yang, J.; Karnes, R.J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Huang, H. Akt-Phosphorylated Foxo1 Suppresses Erk Activation and Chemoresistance by Disrupting Iqgap1-Mapk Interaction. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Wang, G.; Liu, M.; Han, S.; Dong, M.; Peng, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L. Deciphering the Sox4/Mapk1 Regulatory Axis: A Phosphoproteomic Insight into Iqgap1 Phosphorylation and Pancreatic Cancer Progression. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Viswakarma, N.; Principe, D.R.; Das, S.; Sondarva, G.; Nair, R.S.; Srivastava, P.; Sinha, S.C.; Grippo, P.J.; et al. Map4k4 Promotes Pancreatic Tumorigenesis Via Phosphorylation and Activation of Mixed Lineage Kinase 3. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6153–6165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Liang, X.; Liu, K.; Lin, H.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, J.; et al. Gdnf-Induced Phosphorylation of Muc21 Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Perineural Invasion and Metastasis by Activating Rac2 Gtpase. Oncogene 2024, 43, 2564–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased Survival in Pancreatic Cancer with Nab-Paclitaxel Plus Gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, T.; Desseigne, F.; Ychou, M.; Bouche, O.; Guimbaud, R.; Becouarn, Y.; Adenis, A.; Raoul, J.L.; Gourgou-Bourgade, S.; de la Fouchardiere, C.; et al. Folfirinox Versus Gemcitabine for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainberg, Z.A.; Melisi, D.; Macarulla, T.; Pazo Cid, R.; Chandana, S.R.; De La Fouchardiere, C.; Dean, A.; Kiss, I.; Lee, W.J.; Goetze, T.O.; et al. Nalirifox Versus Nab-Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine in Treatment-Naive Patients with Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (Napoli 3): A Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grierson, P.M.; Dodhiawala, P.B.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, T.H.; Khawar, I.A.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, D.; Li, L.; Herndon, J.; Monahan, J.B.; et al. The Mk2/Hsp27 Axis Is a Major Survival Mechanism for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma under Genotoxic Stress. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb5445. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.D.; Metropulos, A.E.; Mubin, N.; Becker, J.H.; Shah, D.; Spaulding, C.; Shields, M.A.; Bentrem, D.J.; Munshi, H.G. Trametinib Potentiates Anti-Pd-1 Efficacy in Tumors Established from Chemotherapy-Primed Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2024, 23, 1854–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, T.; Hammel, P.; Reni, M.; Van Cutsem, E.; Macarulla, T.; Hall, M.J.; Park, J.O.; Hochhauser, D.; Arnold, D.; Oh, D.Y.; et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline Brca-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Tang, R.; Pan, H.; Yang, J.; Tong, X.; Xu, H.; Guo, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wu, D.; Lei, Y.; et al. Tpx2 Serves as a Novel Target for Expanding the Utility of Parpi in Pancreatic Cancer through Conferring Synthetic Lethality. Gut 2025, 74, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ge, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Gao, S.; Shi, L.; Yang, S.; et al. Bzw1 Facilitates Glycolysis and Promotes Tumor Growth in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma through Potentiating Eif2alpha Phosphorylation. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1256–1271.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.F.; Lin, H.R.; Su, Y.H.; Chen, H.A.; Hung, S.W.; Huang, S.Y. The Role of Dicer Phosphorylation in Gemcitabine Resistance of Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zheng, K.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, K.; Ni, C.; Jin, G.; Yu, G. Acot4 Accumulation Via Akt-Mediated Phosphorylation Promotes Pancreatic Tumourigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2021, 498, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.J.; Jin, K.Z.; Li, H.; Ye, L.Y.; Li, P.C.; Jiang, B.; Lin, X.; Liao, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.R.; Shi, S.M.; et al. Siglec15 Amplifies Immunosuppressive Properties of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Lett. 2022, 530, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefler, J.E.; MarElia-Bennett, C.B.; Thies, K.A.; Hildreth, B.E., 3rd; Sharma, S.M.; Pitarresi, J.R.; Han, L.; Everett, C.; Koivisto, C.; Cuitino, M.C.; et al. Stat3 in Tumor Fibroblasts Promotes an Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Pancreatic Cancer. Life Sci. Alliance 2022, 5, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Li, E.; Lao, M.; Tang, T.; Zhang, G.; Guo, C.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; et al. Nek2 Inhibition Triggers Anti-Pancreatic Cancer Immunity by Targeting Pd-L1. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhang, X.; Lao, M.; He, L.; Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Xu, J.; Tang, J.; Hong, Z.; Song, J.; et al. Targeting Leucine-Rich Repeat Serine/Threonine-Protein Kinase 2 Sensitizes Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma to Anti-Pd-L1 Immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. 2023, 31, 2929–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.H.; Yang, W.H.; Xia, W.; Wei, Y.; Chan, L.C.; Lim, S.O.; Li, C.W.; Kim, T.; Chang, S.S.; Lee, H.H.; et al. Metformin Promotes Antitumor Immunity Via Endoplasmic-Reticulum-Associated Degradation of Pd-L1. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 606–620.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Qiao, Q.; Karki, A.; Allison, D.B.; Shaker, N.; Li, K.; Utturkar, S.M.; Atallah Lanman, N.M.; et al. Targeting Plk1 Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer to Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 3532–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Duan, Y.; Hu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Wen, T.; Ouyang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, K.L.; et al. Pck1 Inhibits Cgas-Sting Activation by Consumption of Gtp to Promote Tumor Immune Evasion. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canon, J.; Rex, K.; Saiki, A.Y.; Mohr, C.; Cooke, K.; Bagal, D.; Gaida, K.; Holt, T.; Knutson, C.G.; Koppada, N.; et al. The Clinical Kras(G12c) Inhibitor Amg 510 Drives Anti-Tumour Immunity. Nature 2019, 575, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Allen, S.; Blake, J.F.; Bowcut, V.; Briere, D.M.; Calinisan, A.; Dahlke, J.R.; Fell, J.B.; Fischer, J.P.; Gunn, R.J.; et al. Identification of Mrtx1133, a Noncovalent, Potent, and Selective Kras(G12d) Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 3123–3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, J.; Bowcut, V.; Calinisan, A.; Briere, D.M.; Hargis, L.; Engstrom, L.D.; Laguer, J.; Medwid, J.; Vanderpool, D.; Lifset, E.; et al. Anti-Tumor Efficacy of a Potent and Selective Non-Covalent Kras(G12d) Inhibitor. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2171–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, L.; Zuo, X.; Maitra, A.; Bresalier, R.S. A Small Molecule with Big Impact: Mrtx1133 Targets the Krasg12d Mutation in Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, S.; Kitazawa, M.; Nakamura, S.; Koyama, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hondo, N.; Kataoka, M.; Tanaka, H.; Takeoka, M.; Komatsu, D.; et al. Targeting Kras-Mutant Pancreatic Cancer through Simultaneous Inhibition of Kras, Mek, and Jak2. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyokuni, E.; Horinaka, M.; Nishimoto, E.; Yoshimura, A.; Fukui, M.; Sakai, T. Combination Therapy of Avutometinib and Mrtx1133 Synergistically Suppresses Cell Growth by Inducing Apoptosis in Krasg12d-Mutated Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2025, 24, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Kim, J.; Park, B.; Baylink, D.J.; Kwon, C.; Tran, V.; Lee, S.; Codorniz, K.; Tan, L.; Moreno, P.L.; et al. Targeting DNA Helicase Cmg Complex and Nfkappab2-Driven Drug-Resistant Transcriptional Axis to Effectively Treat Kras(G12d)-Mutated Pancreatic Cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Shen, Q.; Long, R.; Mao, Y.; Tong, S.; Yang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, B. Discovery of Potent and Selective G9a Degraders for the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 13271–13285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulay, K.C.M.; Zhang, X.; Pantazopoulou, V.; Patel, J.; Esparza, E.; Pran Babu, D.S.; Ogawa, S.; Weitz, J.; Ng, I.; Mose, E.S.; et al. Dual Inhibition of Krasg12d and Pan-Erbb Is Synergistic in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 3001–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, S.B.; Cheng, N.; Markosyan, N.; Sor, R.; Kim, I.K.; Hallin, J.; Shoush, J.; Quinones, L.; Brown, N.V.; Bassett, J.B.; et al. Efficacy of a Small-Molecule Inhibitor of Krasg12d in Immunocompetent Models of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, K.K.; McAndrews, K.M.; LeBleu, V.S.; Yang, S.; Lyu, H.; Li, B.; Sockwell, A.M.; Kirtley, M.L.; Morse, S.J.; Moreno Diaz, B.A.; et al. Kras(G12d) Inhibition Reprograms the Microenvironment of Early and Advanced Pancreatic Cancer to Promote Fas-Mediated Killing by Cd8(+) T Cells. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1606–1620.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarasamy, V.; Wang, J.; Frangou, C.; Wan, Y.; Dynka, A.; Rosenheck, H.; Dey, P.; Abel, E.V.; Knudsen, E.S.; Witkiewicz, A.K. The Extracellular Niche and Tumor Microenvironment Enhance Kras Inhibitor Efficacy in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsburn, B.C. Metabolomic, Proteomic, and Single-Cell Proteomic Analysis of Cancer Cells Treated with the Kras(G12d) Inhibitor Mrtx1133. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22, 3703–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, K.; Masutani, T.; Hirokawa, T. Generation of Ks-58 as the First K-Ras(G12d)-Inhibitory Peptide Presenting Anti-Cancer Activity in Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, K.; Qi, Y.; Miyako, E. Nanoformulation of the K-Ras(G12d)-Inhibitory Peptide Ks-58 Suppresses Colorectal and Pancreatic Cancer-Derived Tumors. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, K.; Banna, G.; Liu, S.V.; Friedlaender, A.; Desai, A.; Subbiah, V.; Addeo, A. Drugging Kras: Current Perspectives and State-of-Art Review. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.C.; Manandhar, A.; Carrasco, M.A.; Gurbani, D.; Gondi, S.; Westover, K.D. Biochemical and Structural Analysis of Common Cancer-Associated Kras Mutations. Mol. Cancer Res. 2015, 13, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Herdeis, L.; Rudolph, D.; Zhao, Y.; Bottcher, J.; Vides, A.; Ayala-Santos, C.I.; Pourfarjam, Y.; Cuevas-Navarro, A.; Xue, J.Y.; et al. Pan-Kras Inhibitor Disables Oncogenic Signalling and Tumour Growth. Nature 2023, 619, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, S.A.; Amparo, A.M.; Goodhart, G.; Ahmad, S.A.; Waters, A.M. Evaluation of Kras Inhibitor-Directed Therapies for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1402128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.R.; Tang, J.J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.F.; Liu, Y.X.; Chen, H.; Li, D.; Yi, Z.F.; Gao, J.M. The Natural Product Trienomycin a Is a Stat3 Pathway Inhibitor That Exhibits Potent in Vitro and in Vivo Efficacy against Pancreatic Cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 178, 2496–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, W.; Bian, A.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, Y.; Yin, X.; Ye, J.; Xu, S.; Ti, C.; Sun, Z.; et al. Selectively Targeting Stat3 Using a Small Molecule Inhibitor Is a Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.; Bian, A.; Miao, Y.; Jin, W.; Chen, H.; He, J.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.; Ye, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Discovery of a Highly Potent and Orally Bioavailable Stat3 Dual Phosphorylation Inhibitor for Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 15487–15511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, S.; Singh, S.; Mallareddy, J.R.; Sonawane, Y.A.; Napoleon, J.V.; Rana, S.; Contreras, J.I.; Rajesh, C.; Ezell, E.L.; Kizhake, S.; et al. Structure Activity Relationship (Sar) Study Identifies a Quinoxaline Urea Analog That Modulates Ikkbeta Phosphorylation for Pancreatic Cancer Therapy. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 222, 113579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, R.; Deng, J.; Chen, Q.; Chen, L.; Liang, G.; Chen, X.; Xu, Z. Curcumin Derivative C66 Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Progression through the Inhibition of Jnk-Mediated Inflammation. Molecules 2022, 27, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Hilbert, J.; Genevaux, F.; Hofer, S.; Krauss, L.; Schicktanz, F.; Contreras, C.T.; Jansari, S.; Papargyriou, A.; Richter, T.; et al. A Novel Ampk Inhibitor Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Ferroptosis Induction. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2307695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.D.; Chao, M.W.; Lee, H.Y.; Liu, Y.T.; Tu, H.J.; Lien, S.T.; Lin, T.E.; Sung, T.Y.; Yen, S.C.; Huang, S.H.; et al. In Silico Identification and Biological Evaluation of a Selective Map4k4 Inhibitor against Pancreatic Cancer. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, 38, 2166039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.L.; Wu, Y.W.; Tu, H.J.; Yeh, Y.H.; Lin, T.E.; Sung, T.Y.; Li, M.C.; Yen, S.C.; Hsieh, J.H.; Yu, M.C.; et al. Identification and Biological Evaluation of a Novel Clk4 Inhibitor Targeting Alternative Splicing in Pancreatic Cancer Using Structure-Based Virtual Screening. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2416323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A.; Chen, L.; Xiang, S.; Vangipurapu, R.; Yang, H.; Beato, F.; Fang, B.; Williams, T.M.; Husain, K.; Underwood, P.; et al. Global Phosphoproteomics Reveal Cdk Suppression as a Vulnerability to Kras Addiction in Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4012–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bai, W.; Zhou, T.; Xie, Y.; Yang, B.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Hou, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Sdcbp Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Progression by Preventing Yap1 from Beta-Trcp-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation. Gut 2023, 72, 1722–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, D.; Vucic, D.; Dikic, I. Ubiquitination in Disease Pathogenesis and Treatment. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1242–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Turcu, F.E.; Ventii, K.H.; Wilkinson, K.D. Regulation and Cellular Roles of Ubiquitin-Specific Deubiquitinating Enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009, 78, 363–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracz, M.; Bialek, W. Beyond K48 and K63: Non-Canonical Protein Ubiquitination. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2021, 26, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, L.; Simoneschi, D.; Kurz, E.; Arbini, A.A.; Jang, S.; Guaragnella, N.; Giannattasio, S.; Wang, W.; Chen, Y.A.; Pires, G.; et al. Epigenetic Silencing of the Ubiquitin Ligase Subunit Fbxl7 Impairs C-Src Degradation and Promotes Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toloczko, A.; Guo, F.; Yuen, H.F.; Wen, Q.; Wood, S.A.; Ong, Y.S.; Chan, P.Y.; Shaik, A.A.; Gunaratne, J.; Dunne, M.J.; et al. Deubiquitinating Enzyme Usp9x Suppresses Tumor Growth Via Lats Kinase and Core Components of the Hippo Pathway. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 4921–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, Z.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Jiang, X.; Quan, G.; Jiang, J. Linc00941 Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Malignancy by Interacting with Anxa2 and Suppressing Nedd4l-Mediated Degradation of Anxa2. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Zhu, C.; Liu, P.; Liu, S.; Ren, L.; Lu, R.; Hou, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Pan, Y. Peli1: Key Players in the Oncogenic Characteristics of Pancreatic Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Deng, X.; Liu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Meng, X.; Ma, J. Peli1 Overexpression Contributes to Pancreatic Cancer Progression through Upregulating Ubiquitination-Mediated Inpp5j Degradation. Cell Signal 2024, 120, 111194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Luo, J.; Hu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, J.; Pan, X.; Cao, T.; Xia, J.; et al. Fbxo31 Is Upregulated by Mettl3 to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Progression Via Regulating Sirt2 Ubiquitination and Degradation. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Wang, R.; Chen, G.; Ding, C.; Liu, Y.; Tao, J.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Luo, W.; Weng, G.; et al. Fbxo32 Stimulates Protein Synthesis to Drive Pancreatic Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 2607–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yu, K.; Chen, K.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, T.; Xu, H.; et al. Fbxo45 Facilitates Pancreatic Carcinoma Progression by Targeting Usp49 for Ubiquitination and Degradation. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, H.; Sun, Y.; Guo, F.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, G.; Xia, W.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Ubiquitin Ligase Trim15 Promotes the Progression of Pancreatic Cancer Via the Upregulation of the Igf2bp2-Tlr4 Axis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.J.; Jin, K.Z.; Zhou, H.Y.; Liao, Z.Y.; Zhang, H.R.; Shi, S.M.; Lin, M.X.; Chai, S.J.; Fei, Q.L.; Ye, L.Y.; et al. Deubiquitinating Pabpc1 by Usp10 Upregulates Clk2 Translation to Promote Tumor Progression in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2023, 576, 216411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Shen, B.; Xu, J.; Jiang, J. Usp33 Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Malignant Phenotype through the Regulation of Tgfbr2/Tgfbeta Signaling Pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Li, Q.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, C.; Du, Y.; Yuan, R.; Peng, X. Usp28 Facilitates Pancreatic Cancer Progression through Activation of Wnt/Beta-Catenin Pathway Via Stabilising Foxm1. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Wu, H.; Jin, X. Usp22-Mediated Deubiquitination of Pten Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer Progression by Inducing P21 Expression. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 1200–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, L.; Li, D.; Peng, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Q.; Cao, Q.; Huang, K.; et al. Deubiquitinase Psmd7 Facilitates Pancreatic Cancer Progression through Activating Nocth1 Pathway Via Modifying Sox2 Degradation. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Fan, Z.; Liu, M.; Dong, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Song, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, X.; et al. Usp1 Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Progression and Autophagy by Deubiquitinating Atg14. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Gong, J.; Bai, Y.; Yin, T.; Zhou, M.; Pan, S.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, Y.; et al. A Self-Amplifying Usp14-Taz Loop Drives the Progression and Liver Metastasis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.D.; Du, L.; Cheng, X.C.; Lu, Y.X.; Liu, Q.W.; Wang, Y.W.; Liao, Y.J.; Lin, D.D.; Xiao, F.J. Otub1/Ndufs2 Axis Promotes Pancreatic Tumorigenesis through Protecting against Mitochondrial Cell Death. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, S.; Huang, W.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Feng, D.; Liu, W.; Gao, T.; Ren, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhang, J.; et al. Sirt1 Coordinates with the Crl4b Complex to Regulate Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells to Promote Tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 3329–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Ryu, K.J.; Hong, K.S.; Kim, H.; Han, H.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.; Ok, D.W.; Yang, J.W.; Hwangbo, C.; et al. Erk3 Increases Snail Protein Stability by Inhibiting Fbxo11-Mediated Snail Ubiquitination. Cancers 2023, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Lin, J.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, P.; et al. A Microprotein N1darp Encoded by Linc00261 Promotes Notch1 Intracellular Domain (N1icd) Degradation Via Disrupting Usp10-N1icd Interaction to Inhibit Chemoresistance in Notch1-Hyperactivated Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Discov. 2023, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Jiang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Peng, C.; Peng, H.; Li, X.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, L.; Ma, L.; Sun, T. Trim21-Mediated Mettl3 Degradation Promotes Pdac Ferroptosis and Enhances the Efficacy of Anti-Pd-1 Immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; He, R.; Xia, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhao, C.; Gao, Y.; Shi, Y.; Bai, Y.; et al. Trim21-Promoted Fsp1 Plasma Membrane Translocation Confers Ferroptosis Resistance in Human Cancers. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2302318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, N.; Li, P.; Dong, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zong, W.X.; Gao, S.; Xin, H. Trim21 Ubiquitylates Gpx4 and Promotes Ferroptosis to Aggravate Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Life Sci. 2023, 321, 121608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wei, X.; Xie, Y.; Yan, Y.; Xue, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Pan, Q.; Yan, S.; Zheng, X.; et al. Mdm4 Inhibits Ferroptosis in P53 Mutant Colon Cancer Via Regulating Trim21/Gpx4 Expression. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H. Trim21 Promotes Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis through the Sqstm1-Nrf2-Keap1 Axis to Increase the Titers of H5n1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Yan, D.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Kroemer, G.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; Liu, J. Copper-Dependent Autophagic Degradation of Gpx4 Drives Ferroptosis. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1982–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Ding, C.; Wang, R.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Y.; Tao, J.; Luo, W.; Weng, G.; Yang, G.; Zhang, T. E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Rbck1 Confers Ferroptosis Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer by Facilitating Mfn2 Degradation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 221, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yin, J.; Ma, W.; Liao, H.; Ling, L.; Zou, Q.; Cao, Y.; Song, Y.; Zheng, G.; et al. Targeting Myof Suppresses Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Progression by Inhibiting Ilf3-Lcn2 Signaling through Disrupting Otub1-Mediated Deubiquitination of Ilf3. Redox Biol. 2025, 84, 103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, B.; Du, Y.; Yuan, R.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, W.; Shao, J.; Lu, H.; Yu, Y.; Xiang, M.; Hao, L.; et al. Slc35f2-Syvn1-Trim59 Axis Critically Regulates Ferroptosis of Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Inhibiting Endogenous P53. Oncogene 2023, 42, 3260–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; He, Z.; Cai, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Pang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, X. Trim59/Rbpj Positive Feedback Circuit Confers Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer by Activating the Notch Signaling Pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, S.; Guo, Y.; Sun, C. Oncogenic Trim31 Confers Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer Via Activating the Nf-Kappab Signaling Pathway. Theranostics 2018, 8, 3224–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Jiao, Q.; Ren, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Bi, L. The Interaction between Ubr7 and Prmt5 Drives Pdac Resistance to Gemcitabine by Regulating Glycolysis and Immune Microenvironment. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Yang, Z.; Shi, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhou, F.; Peng, X.; Hong, T.; Jiang, L. E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Ubr5 Promotes Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer by Inducing O-Glcnacylation-Mediated Emt Via Destabilization of Oga. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhou, H.; Wang, K.; Shi, W.; Qin, L.; Guan, J.; Li, L.; Long, B.; et al. Targeting Ube2t Potentiates Gemcitabine Efficacy in Pancreatic Cancer by Regulating Pyrimidine Metabolism and Replication Stress. Gastroenterology 2023, 164, 1232–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, B.; Guo, F.; Wu, H.; Jin, X. Deubiquitination of Fbp1 by Usp7 Blocks Fbp1-Dnmt1 Interaction and Decreases the Sensitivity of Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Parp Inhibitors. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Guo, Y.; Yin, T.; Gou, S.; Xiong, J.; Liang, X.; Lu, C.; Peng, T. Usp8 Promotes Gemcitabine Resistance of Pancreatic Cancer Via Deubiquitinating and Stabilizing Nrf2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yin, T.; Wu, H.; Yang, M. Trim47 Accelerates Aerobic Glycolysis and Tumor Progression through Regulating Ubiquitination of Fbp1 in Pancreatic Cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 166, 105429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yuan, R.; Wen, C.; Liu, T.; Feng, Q.; Deng, X.; Du, Y.; Peng, X. E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Ubr5 Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Growth and Aerobic Glycolysis by Downregulating Fbp1 Via Destabilization of C/Ebpalpha. Oncogene 2021, 40, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; He, X.; Ma, X.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, W. O-Glcnacylation of Fbp1 Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Progression by Facilitating Its Lys48-Linked Polyubiquitination in Hypoxic Environments. Oncogenesis 2025, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.K.; Thin, M.Z.; Evan, T.; Howell, S.; Wu, M.; Almeida, B.; Legrave, N.; Koenis, D.S.; Koifman, G.; Sugimoto, Y.; et al. Usp25 Promotes Pathological Hif-1-Driven Metabolic Reprogramming and Is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Pancreatic Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Xiao, X.; Zou, C.; Mao, Y.; Jin, C.; Fu, D.; Li, R.; Li, H. Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 7 Maintains C-Myc Stability to Support Pancreatic Cancer Glycolysis and Tumor Growth. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, J.; Jiang, J. Kif15 Is Essential for Usp10-Mediated Pgk1 Deubiquitination During the Glycolysis of Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, Z.; Du, Y.; Liu, T.; Xiong, Z.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Peng, X.; Zhou, F. Identification of Stam-Binding Protein as a Target for the Treatment of Gemcitabine Resistance Pancreatic Cancer in a Nutrient-Poor Microenvironment. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ren, D.; Yang, C.; Yang, W.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, X.; Wu, H. Trim15 Promotes the Invasion and Metastasis of Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Mediating Apoa1 Ubiquitination and Degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Dai, Y.; Mo, C.; Li, H.; Luan, X.; Wang, B.; Yang, J.; Jiao, G.; Lu, X.; Chen, Z.; et al. Trim21 Promotes Tumor Growth and Gemcitabine Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer by Inhibiting Ephx1-Mediated Arachidonic Acid Metabolism. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2413674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lao, M.; Yang, H.; Sun, K.; Dong, Y.; He, L.; Jiang, X.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Targeting Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Autophagy Renders Pancreatic Cancer Eradicable with Immunochemotherapy by Inhibiting Adaptive Immune Resistance. Autophagy 2024, 20, 1314–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Lao, M.; Sun, K.; He, L.; Xu, J.; Duan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ying, H.; Li, M.; et al. Targeting Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 8 Sensitizes Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Immunotherapy of Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yan, L.; Qiu, X.; Chen, H.; Gao, F.; Ge, W.; Lian, Z.; Wei, X.; Wang, S.; He, H.; et al. Pak1 Inhibition Increases Trim21-Induced Pd-L1 Degradation and Enhances Responses to Anti-Pd-1 Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Yu, C.; Zeh, H.J.; Kroemer, G.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D.; Kang, R. Tax1bp1-Dependent Autophagic Degradation of Sting1 Impairs Anti-Tumor Immunity. Autophagy 2025, 21, 1802–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, R.; Chen, X.; Yu, C.; Stockwell, B.; Kroemer, G.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Tumor-Specific Gpx4 Degradation Enhances Ferroptosis-Initiated Antitumor Immune Response in Mouse Models of Pancreatic Cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eadg3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, A.; Liu, J.; Du, P.; Li, W.; Quan, H.; Lin, Z.; Chen, L. Taraxasterol Regulates P53 Transcriptional Activity to Inhibit Pancreatic Cancer by Inducing Mdm2 Ubiquitination Degradation. Phytomedicine 2025, 136, 156298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Guan, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, D.; Yu, X.; Li, Q.; Yin, W.; Cheng, X.D.; Zhang, W.; Qin, J.J. Targeting E2 Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme Ubch5c by Small Molecule Inhibitor Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Growth and Metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.; Wei, Y.; Lu, Y.; Dai, E.; Dong, X.; Zhao, B.; Hu, C.; Yuan, L.; et al. Blocking Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 7 Induces Ferroptosis in Gastric Cancer Via Targeting Stearoyl-Coa Desaturase. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2307899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrado, C.; Ashton, N.W.; D’Andrea, A.D.; Yap, T.A. Usp1 Inhibition: A Journey from Target Discovery to Clinical Translation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 271, 108865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, H.Q.; Nie, H.Q.; Feng, M.K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, L.J.; Wang, N.; Liu, H.M.; et al. Usp7 as an Emerging Therapeutic Target: A Key Regulator of Protein Homeostasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, T.; Weinert, B.T.; Choudhary, C. Functions and Mechanisms of Non-Histone Protein Acetylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 156–174, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, W.; Yin, S.; Liang, X.; Chen, T.; Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Bap1 Regulates Hsf1 Activity and Cancer Immunity in Pancreatic Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jin, X.; Yu, H.; Qin, G.; Pan, P.; Zhao, J.; Chen, T.; Liang, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; et al. Hdac5 Modulates Pd-L1 Expression and Cancer Immunity Via P65 Deacetylation in Pancreatic Cancer. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2080–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Han, P.; Chen, C.; Xie, S.; Zhang, H.; Song, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Lian, C. Circptpn22 Attenuates Immune Microenvironment of Pancreatic Cancer Via Stat3 Acetylation. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023, 30, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, C.; Xu, J.; Chen, P.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, J.; Sun, C. Exosome-Derived Fgd5-As1 Promotes Tumor-Associated Macrophage M2 Polarization-Mediated Pancreatic Cancer Cell Proliferation and Metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2022, 548, 215751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fu, H.; Zhu, S.; Xiang, Z.; Fu, H.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, X.; Hu, X.; Chao, M.; et al. The Moonlighting Function of Glutaminase 2 Promotes Immune Evasion of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma by Tubulin Tyrosine Ligase-Like 1-Mediated Yes1 Associated Transcriptional Regulator Glutamylation. Gastroenterology 2025, 168, 1137–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Pan, L.; Zuo, Z.; Li, M.; Zeng, L.; Li, R.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Bai, R.; et al. Linc00842 Inactivates Transcription Co-Regulator Pgc-1alpha to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Malignancy through Metabolic Remodelling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, D.; Attri, K.S.; Shukla, S.K.; Thakur, R.; Chaika, N.V.; He, C.; Wang, D.; Jha, K.; Dasgupta, A.; King, R.J.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Derived Acetate Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Development by Altering Polyamine Metabolism Via the Acss2-Sp1-Sat1 Axis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 613–627, Erratum in Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Shukla, S.K.; Vernucci, E.; He, C.; Wang, D.; King, R.J.; Jha, K.; Siddhanta, K.; Mullen, N.J.; Attri, K.S.; et al. Metabolic Rewiring by Loss of Sirt5 Promotes Kras-Induced Pancreatic Cancer Progression. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1584–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ding, Y.; Jin, J.; Xu, C.; Hu, W.; Wu, S.; Ding, G.; Cheng, R.; Cao, L.; Jia, S. Post-Translational Modification of Cdk1-Stat3 Signaling by Fisetin Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cell Properties. Cell Biosci. 2023, 13, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Xie, D.; Xu, C.; Hu, W.; Kong, B.; Jia, S.; Cao, L. Fisetin Disrupts Mitochondrial Homeostasis Via Superoxide Dismutase 2 Acetylation in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 4628–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, H.; Kato, T.; Murase, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Akahoshi, K.; Ogura, T.; Ogawa, K.; Ban, D.; et al. C646 Inhibits G2/M Cell Cycle-Related Proteins and Potentiates Anti-Tumor Effects in Pancreatic Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Guan, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Chong, D.; Wang, J.Y.; Yu, R.; Yu, W.; et al. Discovery of a Pyrrole-Pyridinimidazole Derivative as Novel Sirt6 Inhibitor for Sensitizing Pancreatic Cancer to Gemcitabine. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looi, C.K.; Gan, L.L.; Sim, W.; Hii, L.W.; Chung, F.F.; Leong, C.O.; Lim, W.M.; Mai, C.W. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors Restore Cancer Cell Sensitivity Towards T Lymphocytes Mediated Cytotoxicity in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atri, P.; Shah, A.; Natarajan, G.; Rachagani, S.; Rauth, S.; Ganguly, K.; Carmicheal, J.; Ghersi, D.; Cox, J.L.; Smith, L.M.; et al. Connectivity Mapping-Based Identification of Pharmacological Inhibitor Targeting Hdac6 in Aggressive Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettermann, K.; Benesch, M.; Weis, S.; Haybaeck, J. Sumoylation in Carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2012, 316, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Li, Z.; Kong, Y.; He, W.; Zheng, H.; An, M.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Kras Mutant-Driven Sumoylation Controls Extracellular Vesicle Transmission to Trigger Lymphangiogenesis in Pancreatic Cancer. J. Clin. Investg. 2022, 132, e157644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, W.; Lee, K.L.; Ding, L.W.; Wuensche, P.; Kato, H.; Doan, N.B.; Poellinger, L.; Said, J.W.; Koeffler, H.P. Pias4 Is an Activator of Hypoxia Signalling Via Vhl Suppression During Growth of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Tian, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, S.; Li, T.; Xia, R.; He, R.; Luo, Y.; Lin, Q.; Fu, Z.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle-Packaged Circbirc6 from Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Induce Platinum Resistance Via Sumoylation Modulation in Pancreatic Cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swayden, M.; Alzeeb, G.; Masoud, R.; Berthois, Y.; Audebert, S.; Camoin, L.; Hannouche, L.; Vachon, H.; Gayet, O.; Bigonnet, M.; et al. Pml Hyposumoylation Is Responsible for the Resistance of Pancreatic Cancer. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 12447–12463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauth, S.; Karmakar, S.; Shah, A.; Seshacharyulu, P.; Nimmakayala, R.K.; Ganguly, K.; Bhatia, R.; Muniyan, S.; Kumar, S.; Dutta, S.; et al. Sumo Modification of Paf1/Pd2 Enables Pml Interaction and Promotes Radiation Resistance in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 41, e0013521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, J.H.; Xu, L.; Li, Y.X.; Zhu, X.X.; Wang, X.Y.; Wu, X.; Zhao, W.; Ni, X.; Yin, X.Y. Sumo Specific Peptidase 3 Halts Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Metastasis Via Desumoylating Dkc1. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 1742–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Fan, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, D.; Yan, D. Hypoxia-Induced Nfatc3 Desumoylation Enhances Pancreatic Carcinoma Progression. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Schoonderwoerd, M.J.A.; Kroonen, J.S.; de Graaf, I.J.; Sluijter, M.; Ruano, D.; Gonzalez-Prieto, R.; Verlaan-de Vries, M.; Rip, J.; Arens, R.; et al. Targeting Pancreatic Cancer by Tak-981: A Sumoylation Inhibitor That Activates the Immune System and Blocks Cancer Cell Cycle Progression in a Preclinical Model. Gut 2022, 71, 2266–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, B.R.; Dao, T.T.P.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Son, H.; Jo, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Suh, Y.J.; et al. Tak-981, a Sumoylation Inhibitor, Suppresses Aml Growth Immune-Independently. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 3155–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabellier, L.; De Toledo, M.; Chakraborty, M.; Akl, D.; Hallal, R.; Aqrouq, M.; Buonocore, G.; Recasens-Zorzo, C.; Cartron, G.; Delort, A.; et al. Sumoylation Inhibitor Tak-981 (Subasumstat) Synergizes with 5-Azacytidine in Preclinical Models of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Haematologica 2024, 109, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biederstadt, A.; Hassan, Z.; Schneeweis, C.; Schick, M.; Schneider, L.; Muckenhuber, A.; Hong, Y.; Siegers, G.; Nilsson, L.; Wirth, M.; et al. Sumo Pathway Inhibition Targets an Aggressive Pancreatic Cancer Subtype. Gut 2020, 69, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic Regulation of Gene Expression by Histone Lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Yang, X.; Xu, C.; Song, Q.; Zhao, H.; Sun, T.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, G.; Xue, Y.; et al. Sirt4 Promotes Pancreatic Cancer Stemness by Enhancing Histone Lactylation and Epigenetic Reprogramming Stimulated by Calcium Signaling. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2412553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Hu, C.; Huang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, Q.; Chen, H.; He, R.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, H.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Foster a High-Lactate Microenvironment to Drive Perineural Invasion in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 2199–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, T.; Cai, A.; Han, B.; Li, Y.; Fang, Z.; Yu, D.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J.; et al. Vsig4(+) Tumor-Associated Macrophages Mediate Neutrophil Infiltration and Impair Antigen-Specific Immunity in Aggressive Cancers through Epigenetic Regulation of Spp1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Lin, H.; Zhao, D.; Ye, M.; Zhang, S.; et al. Elevated Protein Lactylation Promotes Immunosuppressive Microenvironment and Therapeutic Resistance in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J. Clin. Investg. 2025, 135, e187024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Yi, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, S.; Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Li, F. Rhof Promotes Snail1 Lactylation by Enhancing Pkm2-Mediated Glycolysis to Induce Pancreatic Cancer Cell Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Cancer Metab. 2024, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Luo, G.; Peng, K.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Qiu, X.; Pu, M.; Liu, X.; et al. Lactylation Stabilizes Tfeb to Elevate Autophagy and Lysosomal Activity. J. Cell Biol. 2024, 223, e202308099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.R.; Hart, G.W. Topography and Polypeptide Distribution of Terminal N-Acetylglucosamine Residues on the Surfaces of Intact Lymphocytes. Evidence for O-Linked Glcnac. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 3308–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreppel, L.K.; Hart, G.W. Regulation of a Cytosolic and Nuclear O-Glcnac Transferase. Role of the Tetratricopeptide Repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 32015–32022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubas, W.A.; Hanover, J.A. Functional Expression of O-Linked Glcnac Transferase. Domain Structure and Substrate Specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 10983–10988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wells, L.; Comer, F.I.; Parker, G.J.; Hart, G.W. Dynamic O-Glycosylation of Nuclear and Cytosolic Proteins: Cloning and Characterization of a Neutral, Cytosolic Beta-N-Acetylglucosaminidase from Human Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 9838–9845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhou, H.; Wu, L.; Lai, Z.; Geng, D.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Z.; Qin, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. O-Glcnacylation Promotes Pancreatic Tumor Growth by Regulating Malate Dehydrogenase 1. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, L.; Lou, J.; Lin, C.; Gong, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, Y. O-Glcnacylation and Stablization of Sirt7 Promote Pancreatic Cancer Progression by Blocking the Sirt7-Reggamma Interaction. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.S.; Gupta, V.K.; Dauer, P.; Kesh, K.; Hadad, R.; Giri, B.; Chandra, A.; Dudeja, V.; Slawson, C.; Banerjee, S.; et al. O-Glcnac Modification of Sox2 Regulates Self-Renewal in Pancreatic Cancer by Promoting Its Stability. Theranostics 2019, 9, 3410–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, C.; Deng, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, J.; Byers, S.; Moremen, K.W.; Pei, H.; Ma, J. Ultradeep O-Glcnac Proteomics Reveals Widespread O-Glcnacylation on Tyrosine Residues of Proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2409501121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motolani, A.; Martin, M.; Wang, B.; Jiang, G.; Alipourgivi, F.; Huang, X.; Safa, A.; Liu, Y.; Lu, T. Critical Role of Novel O-Glcnacylation of S550 and S551 on the P65 Subunit of Nf-Kappab in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Qin, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Popp, M.; Popp, F.; Alakus, H.; Kong, B.; Dong, Q.; et al. Inflammatory Ifit3 Renders Chemotherapy Resistance by Regulating Post-Translational Modification of Vdac2 in Pancreatic Cancer. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7178–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.R.; Li, T.J.; Yu, X.J.; Liu, C.; Wu, W.D.; Ye, L.Y.; Jin, K.Z. The Gfpt2-O-Glcnacylation-Ybx1 Axis Promotes Il-18 Secretion to Regulate the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Iovanna, J.; Santofimia-Castano, P. Targeting Fibrosis: The Bridge That Connects Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, N.; Klein, L.; Wegwitz, F.; Espinet, E.; Maurer, H.C.; Tu, M.; Penz, F.; Kuffer, S.; Xu, X.; Bohnenberger, H.; et al. Axon Guidance Receptor Robo3 Modulates Subtype Identity and Prognosis Via Axl-Associated Inflammatory Network in Pancreatic Cancer. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e154475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Pichlmeier, S.; Denz, A.M.; Schreiner, N.; Straub, T.; Benitz, S.; Wolff, J.; Fahr, L.; Del Socorro Escobar Lopez, M.; Kleeff, J.; et al. Altered Histone Acetylation Patterns in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines Induce Subtype-Specific Transcriptomic and Phenotypical Changes. Int. J. Oncol. 2024, 64, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muneer, G.; Gebreyesus, S.T.; Chen, C.S.; Lee, T.T.; Yu, F.; Lin, C.A.; Hsieh, M.S.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Ho, C.C.; Yu, S.L.; et al. Mapping Nanoscale-to-Single-Cell Phosphoproteomic Landscape by Chip-Dia. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2402421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, Y.; Qin, R.; Li, Y. Post-Translational Modifications: Key “Regulators” of Pancreatic Cancer Malignant Phenotype—Advances in Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123013

Shi Y, Qin R, Li Y. Post-Translational Modifications: Key “Regulators” of Pancreatic Cancer Malignant Phenotype—Advances in Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123013

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Yongkang, Renyi Qin, and Yiming Li. 2025. "Post-Translational Modifications: Key “Regulators” of Pancreatic Cancer Malignant Phenotype—Advances in Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123013

APA StyleShi, Y., Qin, R., & Li, Y. (2025). Post-Translational Modifications: Key “Regulators” of Pancreatic Cancer Malignant Phenotype—Advances in Mechanisms and Targeted Therapies. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123013