Sex-Specific Electrocortical Interactions in a Color Recognition Task in Men and Women with Opioid Use Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Significance

1.2. Biomarkers for Dopamine in Substance Abuse Disorders

1.3. Electrocortical Activity in Opioid Use Disorder

1.4. Rationale and Hypotheses

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Participants

2.3. Electroencephalographic Evoked-Potential Recordings with a Dense Array Sensor Net

2.4. Color Processing Task

2.5. General Behavioral Procedures

2.6. Hardy-Rand-Rittler (HRR) Pseudoisochromatic Test

2.7. Finger Tapping Test

2.8. Symbol Digit Modalities Test© (SDMT)

2.9. Trail Making Test, Parts A or B (Trails A/B)

2.10. Binocular Rivalry Test

2.11. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sex Differences in Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) in a Color Recognition Go/No-Go Task in Non-OUD Control Subjects

3.2. Color Differences in Event-Related Potentials in a Color Recognition Task in Non-OUD Control Subjects

3.3. Event-Related Potentials in a Color Recognition Task in OUD

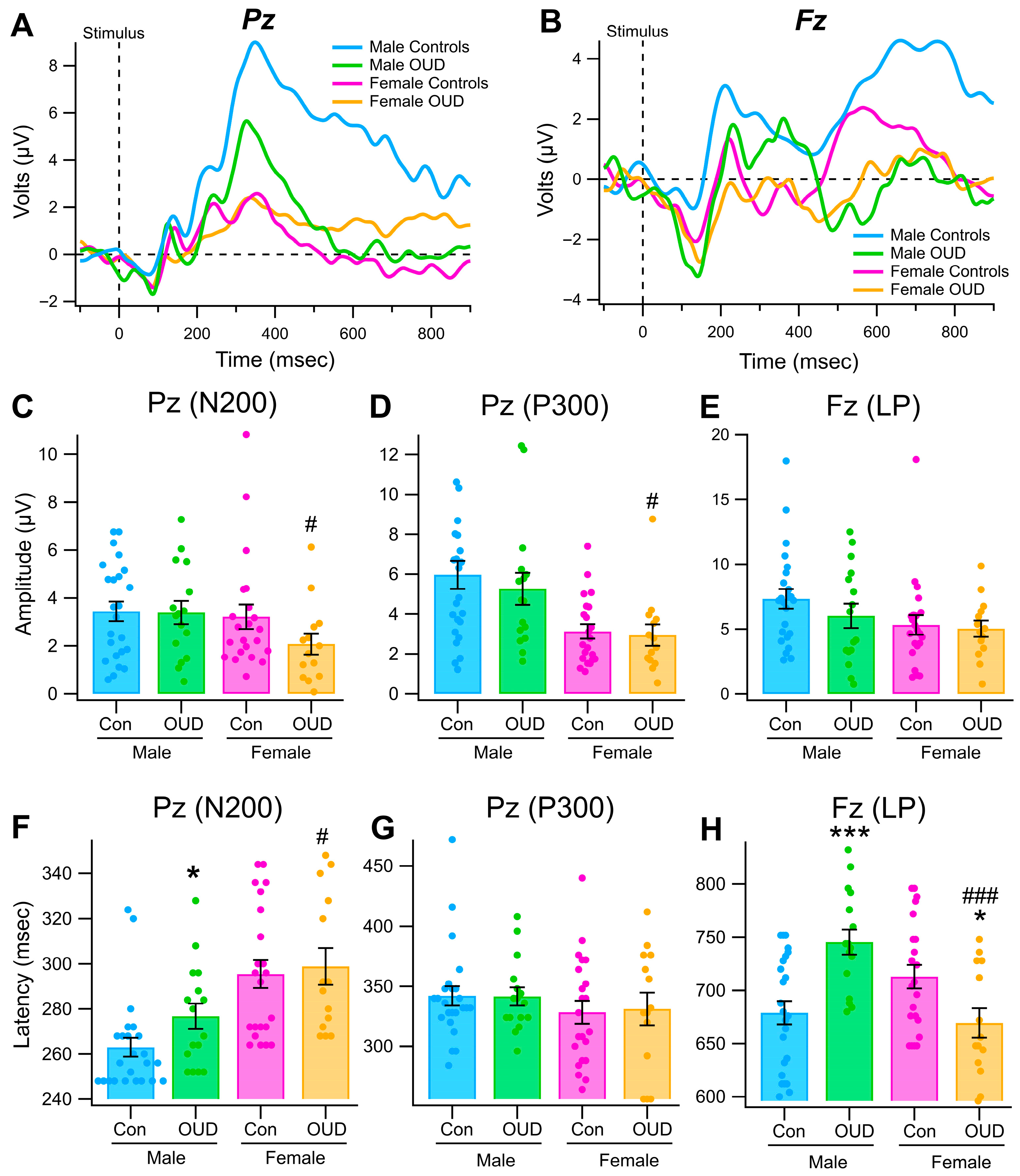

3.4. Effects of Sex and OUD on Reaction Time in the Color Recognition Task

3.5. Color Differences in Binocular Rivalry in OUD

3.6. Effects of Sex and OUD on Neuropsychological Tests

4. Discussion

- N200, P300, and late potential (LP) Relevant stimulus-induced ERPs were evoked by the simple color processing Go/No-Go task and were well-differentiated from Irrelevant distractor stimuli.

- P300 amplitudes were significantly greater and N200 and LP latencies significantly shorter in male vs. female non-OUD controls in this task.

- N200, P300, and LP ERP amplitudes and/or latencies were significantly affected to varying degrees by sex and OUD, but most significance was found with the LP, latencies, and blue color, some at p < 0.0001 levels of significance.

- In the Binocular Rivalry Test, there were shorter dwell times for perceiving a blue stimulus in male OUD subjects.

- There were significant sex and OUD differences in neuropsychological tests including Finger Tapping, Trails A/B, and Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

- Although these findings are remarkable and significant, these measures may not be reliable as effective indices for a biomarker of brain DA in SUD, as an effective biomarker must demonstrate both exceptional analytic reliability, reproducibility, and accuracy.

- Our study provides compelling evidence that the simple color discrimination task used in the current study is sensitive to sex and OUD differences and may provide the basis for the development of an effective biomarker for better understanding the biological underpinnings of substance abuse addiction and as an objective index of mesolimbic DA transmission and monitoring of treatment efficacy.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DA | Dopamine |

| OUD | Opioid use disorder |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| ERP | Event-related potential |

| VEP | Visual evoked potential |

| SUD | Substance Use Disorder |

| RT | Reaction time |

| UA | Urinalysis |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- National Institute on Drugs and Addiction (NIDA). NIDA IC Fact Sheet 2024: The Addiction Public Health Crisis; National Institute on Drugs and Addiction (NIDA): North Bethesda, MD, USA, 2024; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Fentanyl DrugFacts: What Is Fentanyl? National Institute on Drugs and Addiction (NIDA): North Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/fentanyl (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Butelman, E.R.; Huang, Y.; Epstein, D.H.; Shaham, Y.; Goldstein, R.Z.; Volkow, N.D.; Alia-Klein, N. Overdose mortality rates for opioids and stimulant drugs are substantially higher in men than in women: State-level analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Febo, M.; Thanos, P.K.; Baron, D.; Fratantonio, J.; Gold, M. Clinically combating reward deficiency syndrome (RDS) with dopamine agonist therapy as a paradigm shift: Dopamine for dinner? Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 52, 1862–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T.E.; Berridge, K.C. The Incentive-Sensitization Theory of Addiction 30 Years On. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2025, 76, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Koroshetz, W.J. The role of neurologists in tackling the opioid epidemic. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, R.A.; Hoffman, D.C. Localization of drug reward mechanisms by intracranial injections. Synapse 1992, 10, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkashef, A.; Vocci, F. Biological markers of cocaine addiction: Implications for medications development. Addict. Biol. 2003, 8, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, S.E.; Malenka, R.C.; Nestler, E.J. Neural mechanisms of addiction: The role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 29, 565–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manejwala, O. Craving: Why We Can’t Seem to Get Enough; Hazelden Publishing: Center City, MN, USA, 2013; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Manejwala, O.S. Redefining addiction treatment. Behav. Healthc. 2011, 31, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Huang, L.C.; Lin, S.H.; Yang, Y.K. Dopaminergic and glutamatergic biomarkers disruption in addiction and regulation by exercise: A mini review. Biomarkers 2022, 27, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, J.B.; Chartoff, E. Sex differences in neural mechanisms mediating reward and addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Febo, M.; DBadgaiyan, R.; Demetrovics, Z.; Simpatico, T.; Fahlke, C.; Oscar-Berman, M.; Li, M.; Dushaj, K.; Gold, M.S. Common Neurogenetic Diagnosis and Meso-Limbic Manipulation of Hypodopaminergic Function in Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS): Changing the Recovery Landscape. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, E.R.; Dennen, C.A.; Gold, M.S.; Bowirrat, A.; Gupta, A.; Baron, D.; Roy, A.K.; Smith, D.E.; Cadet, J.L.; Blum, K. Proposing a “Brain Health Checkup (BHC)” as a Global Potential “Standard of Care” to Overcome Reward Dysregulation in Primary Care Medicine: Coupling Genetic Risk Testing and Induction of “Dopamine Homeostasis”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez Olguín, H.; Calderón Guzmán, D.; Hernández García, E.; Barragán Mejía, G. The Role of Dopamine and Its Dysfunction as a Consequence of Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 9730467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madras, B.K. Dopamine challenge reveals neuroadaptive changes in marijuana abusers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 11915–11916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D. Stimulant medications: How to minimize their reinforcing effects? Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Koob, G.; Baler, R. Biomarkers in substance use disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziv, I.; Melamed, E.; Nardi, N.; Luria, D.; Achiron, A.; Offen, D.; Barzilai, A. Dopamine induces apoptosis-like cell death in cultured chick sympathetic neurons—A possible novel pathogenetic mechanism in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 1994, 170, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappa, K.A. Evoked Potentials in Clinical Medicine, 3rd ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: New York, NY, USA, 1997; p. 720. [Google Scholar]

- Luck, S.J. An Introduction to the Event-Related Potential Technique; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; p. 375. [Google Scholar]

- Kouri, E.M.; Lukas, S.E.; Mendelson, J.H. P300 assessment of opiate and cocaine users: Effects of detoxification and buprenorphine treatment. Biol. Psychiatry 1996, 40, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polich, J. Clinical application of the P300 event-related brain potential. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 15, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begleiter, H.; Porjesz, B. Genetics of human brain oscillations. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2006, 60, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukas, S.E.; Mendelson, J.H.; Kouri, E.; Bolduc, M.; Amass, L. Ethanol-induced alterations in EEG alpha activity and apparent source of the auditory P300 evoked response potential. Alcohol 1990, 7, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopell, B.S.; Roth, W.T.; Tinklenberg, J.R. Time course effects of marijuana and ethanol on event-related potentials. Psychopharmacology 1978, 56, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begleiter, H.; Porjesz, B.; Tenner, M. Neuroradiological and neurophysiological evidence of brain deficits in chronic alcoholics. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1980, 286, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, A.; Horvath, T.B.; Roth, W.T.; Kopell, B.S. Event-related potential changes in chronic alcoholics. Electroencephalogr. Soc. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1979, 47, 637–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attou, A.; Figiel, C.; Timsit-Berthier, M. Opioid addiction: P300 assessment in treatment by methadone substitution. Neurophysiol. Clin. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 31, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.O. CNS recovery from cocaine, cocaine and alcohol, or opioid dependence: A P300 study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001, 112, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, A.; Horvath, T.B.; Roth, W.T.; Clifford, S.T.; Kopell, B.S. Acute and chronic effects of ethanol on event-related potentials. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1980, 126, 625–639. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, J.; Kowallis, L.R.; Kamhout, S.; Bills, K.B.; Adams, D.; Fleming, D.E.; Brown, B.L.; Steffensen, S.C. Gender-Specific Interactions in a Visual Object Recognition Task in Persons with Opioid Use Disorder. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffensen, S.C.; Ohran, A.J.; Shipp, D.N.; Hales, K.; Stobbs, S.H.; Fleming, D.E. Gender-selective effects of the P300 and N400 components of the visual evoked potential. Vis. Res. 2008, 48, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, M. The Effect of Menstrual Phases on Visual Attention and Event-Related Potentials. Unpublished. Master’s Thesis, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.M. Association Between Academic Performance and Electro-Cortical Processing of Cognitive Stimuli in College Students. Master’s Thesis, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, USA, 2011. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Concato, M.; Giacomello, E.; Al-Habash, I.; Alempijevic, D.; Kolev, Y.G.; Buffon, M.; Radaelli, D.; D’Errico, S. Molecular Sex Differences and Clinical Gender Efficacy in Opioid Use Disorders: From Pain Management to Addiction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVito, E.E.; Ameral, V.; Sofuoglu, M. Sex differences in comorbid pain and opioid use disorder: A scoping review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 3067–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colzato, L.S.; Sellaro, R.; Hulka, L.M.; Quednow, B.B.; Hommel, B. Cognitive control predicted by color vision, and vice versa. Neuropsychologia 2014, 62, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, B.K.; Day, J.E.; Rollins, D.E.; Andrenyak, D.; Ling, W.; Wilkins, D.G. Opiate recidivism in a drug-treatment program: Comparison of hair and urine data. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2003, 27, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, H. Progress and problems in brain research. J. Mt. Sinai Hosp. 1958, 25, 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 9.2 User’s Guide; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.B.; van Steenbergen, H.; Band, G.P.; de Rover, M.; Nieuwenhuis, S. Functional significance of the emotion-related late positive potential. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.E.; Payne, R.L.; Wahlquist, A.H.; Carter, R.E.; Stroud, Z.; Haynes, L.; Hillhouse, M.; Brady, K.T.; Ling, W. Comparative profiles of men and women with opioid dependence: Results from a national multisite effectiveness trial. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2011, 37, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, A.B.; Grella, C.E. Gender differences among older heroin users. J. Women Aging 2009, 21, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, P.; Roy, M.; Roy, A.; Brown, S.; Smelson, D. Impaired color vision in cocaine-withdrawn patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Roy, M.; Berman, J.; Gonzalez, B. Blue cone electroretinogram amplitudes are related to dopamine function in cocaine-dependent patients. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 117, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, M.; Roy, A.; Smelson, D.; Brown, S.; Weinberger, L. Reduced blue cone electroretinogram in withdrawn cocaine dependent patients: A replication. Biol. Psychiatry 1997, 42, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Roy, A.; Williams, J.; Weinberger, L.; Smelson, D. Reduced blue cone electroretinogram in cocaine-withdrawn patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Smelson, D.; Roy, A. Longitudinal study of blue cone retinal function in cocaine-withdrawn patients. Biol. Psychiatry 1997, 41, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballenger, J.C.; Post, R.M. Kindling as a model for alcohol withdrawal syndromes. Br. J. Psychiatry 1978, 133, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smookler, H.H.; Buckley, J.P. Effect of drugs on animals exposed to chronic environmental stress. Fed. Proc. 1970, 29, 1980–1984. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, G.; Oliveto, A.; Kosten, T.R. Combating opiate dependence: A comparison among the available pharmacological options. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2004, 5, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubman, D.I.; Yücel, M.; Kettle, J.W.; Scaffidi, A.; MacKenzie, T.; Simmons, J.G.; Allen, N.B. Responsiveness to drug cues and natural rewards in opiate addiction: Associations with later heroin use. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, J.D.; McKenzie, M.; Shield, D.C.; Wolf, F.A.; Key, R.G.; Poshkus, M.; Clarke, J. Linkage with methadone treatment upon release from incarceration: A promising opportunity. J. Addict. Disord. 2005, 24, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, F.J.; Kalivas, P.W. Neuroadaptations involved in amphetamine and cocaine addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998, 51, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.L. Electrophysiological Components in Children with ADHD with Attention Deficit Disorder with or Without Hyperactivity (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation); University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Frith, C.D.; Friston, K.J. The role of the thalamus in “top down” modulation of attention to sound. Neuroimage 1996, 4, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Color Wavelength | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERP | Sex | Red M (SD) | Green M (SD) | Blue M (SD) |

| N200 | Male | 2.25 (1.94) n = 30 | 2.03 (1.24) n = 31 | 2.64 (1.20) n = 31 |

| Female | 1.87 (1.38) n = 21 | 1.99 (1.47) n = 21 | 1.85 (0.90) n = 22 | |

| P300 | Male | 3.96 (1.89) n = 30 | 4.12 (2.03) n = 31 | 4.34 (1.55) n = 31 |

| Female | 4.02 (2.72) n = 21 | 4.31 (3.02) n = 21 | 2.22 (0.87) n =22 ** | |

| LP | Male | 2.92 (1.80) n = 31 | 2.88 (2.56) n = 31 | 5.43 (2.26) n = 31 |

| Female | 1.92 (0.84) n = 21 *** | 2.50 (1.33) n = 21 *** | 4.63 (2.66) n = 22 *** | |

| ERP | Factors | t | p | b | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N200 | Sex: female | −0.75 | 0.455 | −0.37 | [−1.36, 0.62] |

| Color: green | −0.63 | 0.534 | −0.22 | [−0.94, 0.49] | |

| Color: blue | 0.92 | 0.361 | 0.39 | [−0.46, 1.24] | |

| Interaction: female × green | 0.60 | 0.554 | 0.33 | [−0.79, 1.46] | |

| Interaction: female × blue | −0.63 | 0.533 | −0.42 | [−1.77, 2.89] | |

| P300 | Sex: female | 0.12 | 0.904 | 0.08 | [−1.22, 1.38] |

| Color: green | 0.38 | 0.706 | 0.20 | [−0.84, 1.23] | |

| Color: blue | 0.85 | 0.401 | 0.42 | [−0.58, 1.42] | |

| Interaction: female × green | 0.16 | 0.875 | 0.13 | [−1.49, 1.75] | |

| Interaction: female × blue | −2.79 | 0.007 | −2.20 | [−3.78, −0.62] | |

| LP | Sex: female | −2.22 | 0.031 | −0.95 | [−1.80, −0.09] |

| Color: green | −0.07 | 0.945 | −0.03 | [−0.96, 0.90] | |

| Color: blue | 5.85 | <0.001 | 2.51 | [1.65, 3.38] | |

| Interaction: female × green | 0.76 | 0.451 | 0.56 | [−0.91, 2.02] | |

| Interaction: female × blue | 0.21 | 0.833 | 0.15 | [−1.25, 1.54] |

| AMP | LAT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERP | Contrasts | F | p | F | p |

| N200 | Men vs. Women Controls | 51.8 | <0.0001 *** | 96.33 | <0.0001 *** |

| Controls vs. OUD | 0.94 | 0.33 | 5.1 | 0.02 * | |

| Men Controls vs. Men OUD | 4.62 | 0.03 * | 6.7 | 0.01 * | |

| Women Controls vs. Women OUD | 0.44 | 0.5 | 0.47 | 0.49 | |

| P300 | Men vs. Women Controls | 123.2 | <0.0001 *** | 2.3 | 0.13 |

| Controls vs. OUD | 2.61 | 0.11 | 1.15 | 0.29 | |

| Men Controls vs. Men OUD | 8.95 | 0.003 ** | 5.5 | 0.02 * | |

| Women Controls vs. Women OUD | 0.3 | 0.57 | 0.5 | 0.48 | |

| LP | Men vs. Women Controls | 58.1 | <0.0001 *** | 43.2 | <0.0001 *** |

| Controls vs. OUD | 2.3 | 0.13 | 39.4 | <0.0001 *** | |

| Men Controls vs. Men OUD | 1.92 | 0.17 | 288.25 | <0.0001 *** | |

| Women Controls vs. Women OUD | 0.59 | 0.44 | 50.7 | <0.0001 *** | |

| Tests | Group Comparisons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls M (SD) (n = 31) ± vs. Addiction M (SD) (n = 38) | FC M (SD) (n = 16) vs. MC M (SD) (n = 15) | FA M (SD) (n = 19) vs. MA M (SD) (n = 19) | MC M (SD) (n = 15) vs. MA M (SD) (n =19) | FC M (SD) (n = 16) vs. FA M (SD) (n = 19) | |

| Finger Tapping | 51.3 (7.2) 51.1 (7.2) | 46.9 (7.0) 55.9 (3.7) *** | 48.2 (4.5) 54.1 (4.9) | 55.9 (3.7) 54.1 (4.9) | 46.9 (7.0) 48.2 (4.5) |

| Trails A | 19.3 (5.2) (n = 15) | 19.7 (4.9) (n = 6) | 25.1 (5.8) (n = 9) | 18.8 (6.0) (n = 9) | 19.7 (4.9) (n = 6) |

| 26.3 (7.1) * (n = 19) | 18.8 (6.0) (n = 9) | 27.3 (8.2) (n = 10) | 27.3 (8.2) * (n = 10) | 25.1 (5.8) * (n = 9) | |

| Trails B | 54.7 (23.4) (n = 15) | 44.6 (10) (n = 7) | 73.5 (31.3) (n = 11) | 63.5 (28.6) (n = 8) | 44.6 (10) (n = 7) |

| 72.2 (28.8) * (n = 20) | 63.5 (28.6) (n = 8) | 70.6 (27.3) (n = 9) | 70.6 (27.3) (n = 9) | 73.5 (31.3) * (n = 11) | |

| Symbol Digit Modalities Test | 50.6 (8.3) 62.1 (11.1) *** | 61.4 (10.2) 62.8 (12.4) | 52.4 (7.8) 48.8 (8.6) | 62.8 (12.4) 48.8 (8.6) *** | 61.4 (10.2) 52.4 (7.8) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petrie, J.A.; Trikha, A.; Lundberg, H.L.; Bills, K.B.; Manwaring, P.K.; Obray, J.D.; Adams, D.N.; Brown, B.L.; Fleming, D.E.; Steffensen, S.C. Sex-Specific Electrocortical Interactions in a Color Recognition Task in Men and Women with Opioid Use Disorder. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123002

Petrie JA, Trikha A, Lundberg HL, Bills KB, Manwaring PK, Obray JD, Adams DN, Brown BL, Fleming DE, Steffensen SC. Sex-Specific Electrocortical Interactions in a Color Recognition Task in Men and Women with Opioid Use Disorder. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123002

Chicago/Turabian StylePetrie, Jo Ann, Abhishek Trikha, Hope L. Lundberg, Kyle B. Bills, Preston K. Manwaring, J. Daniel Obray, Daniel N. Adams, Bruce L. Brown, Donovan E. Fleming, and Scott C. Steffensen. 2025. "Sex-Specific Electrocortical Interactions in a Color Recognition Task in Men and Women with Opioid Use Disorder" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123002

APA StylePetrie, J. A., Trikha, A., Lundberg, H. L., Bills, K. B., Manwaring, P. K., Obray, J. D., Adams, D. N., Brown, B. L., Fleming, D. E., & Steffensen, S. C. (2025). Sex-Specific Electrocortical Interactions in a Color Recognition Task in Men and Women with Opioid Use Disorder. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3002. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123002