Comparative Investigation of the Effects of Adenosine Triphosphate, Melatonin, and Thiamine Pyrophosphate on Amiodarone-Induced Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain in Male Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Reagents and Chemicals

2.3. Experimental Design and Randomization

2.4. Experimental Groups

2.5. Experimental Procedure

2.6. Biochemical Analyses

2.6.1. Preparation of Samples

2.6.2. Determination of MDA, tGSH, SOD, CAT, and Total Protein Levels in Sciatic Nerve Tissue

2.6.3. Determination of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 Levels in Sciatic Nerve Tissue

2.7. Histopathological Procedures

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Biochemical Findings

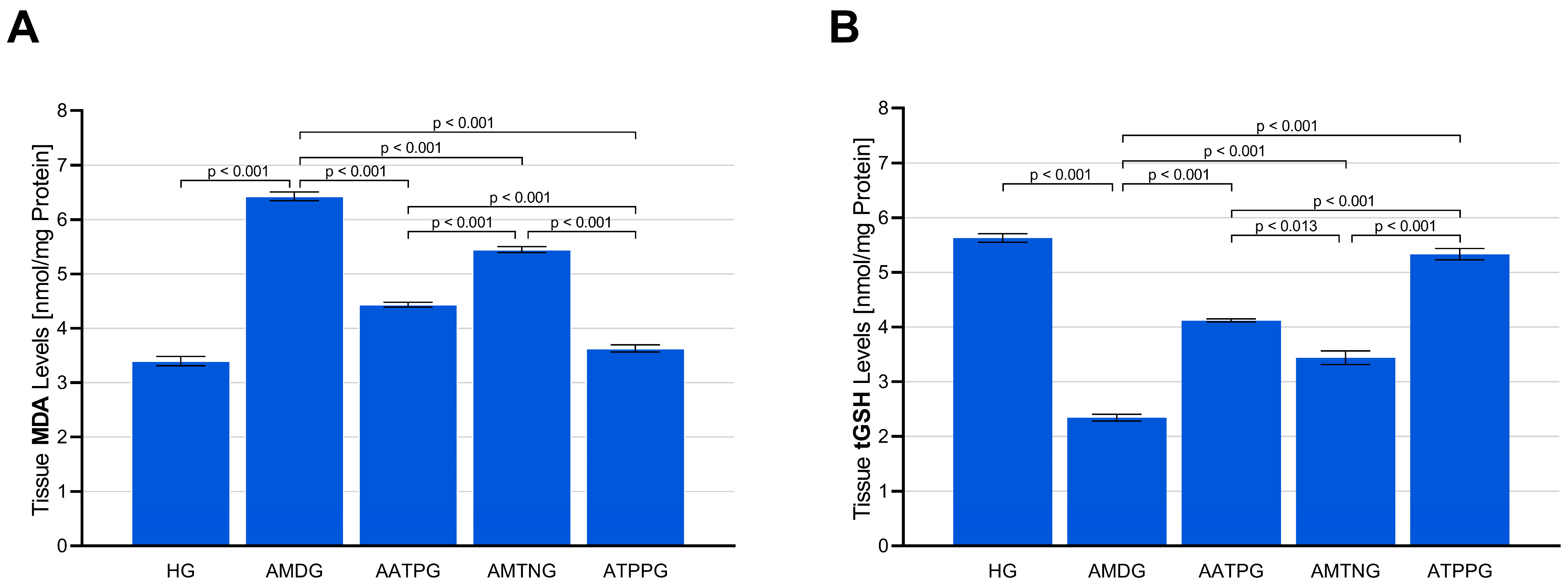

3.1.1. Analysis of MDA and tGSH Levels in Sciatic Nerve Tissue

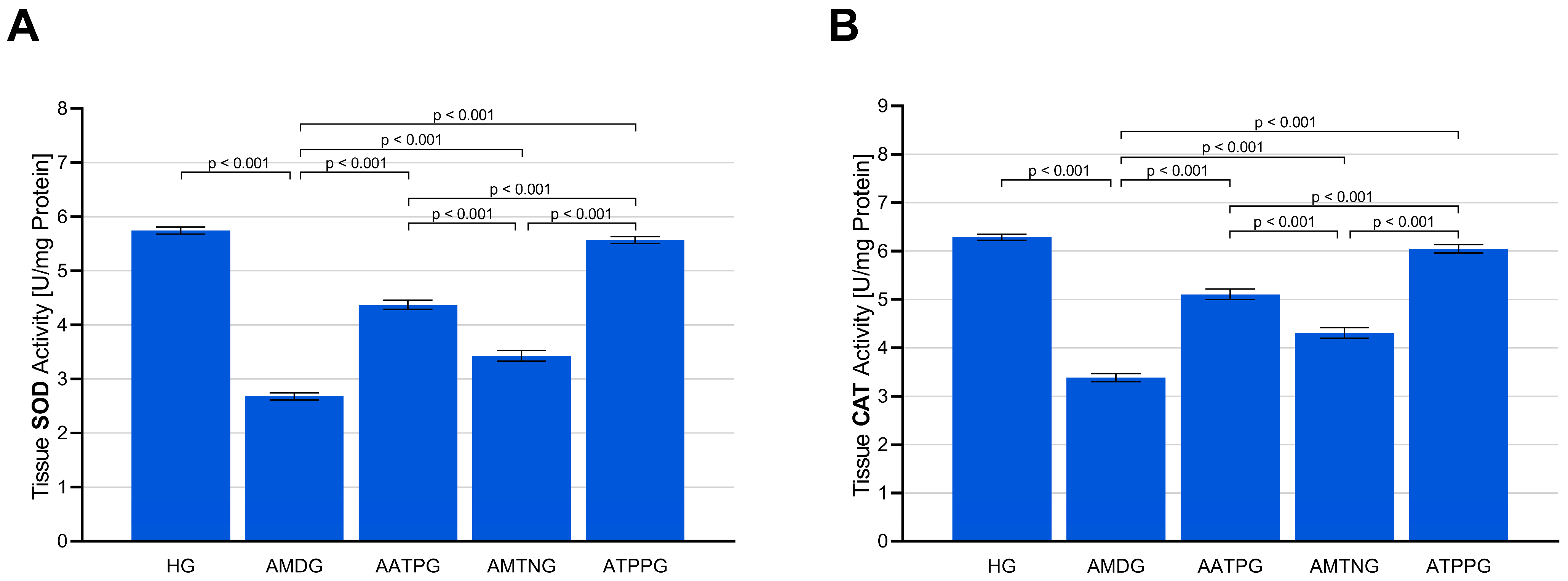

3.1.2. Analysis of SOD and CAT Activities in Sciatic Nerve Tissue

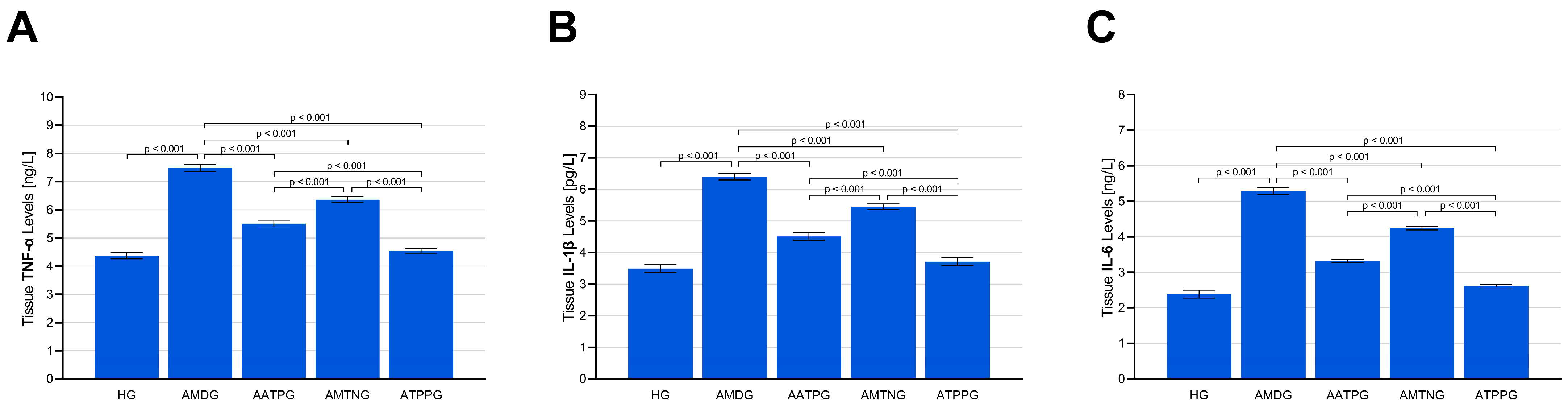

3.1.3. Analysis of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 Levels in Sciatic Nerve Tissue

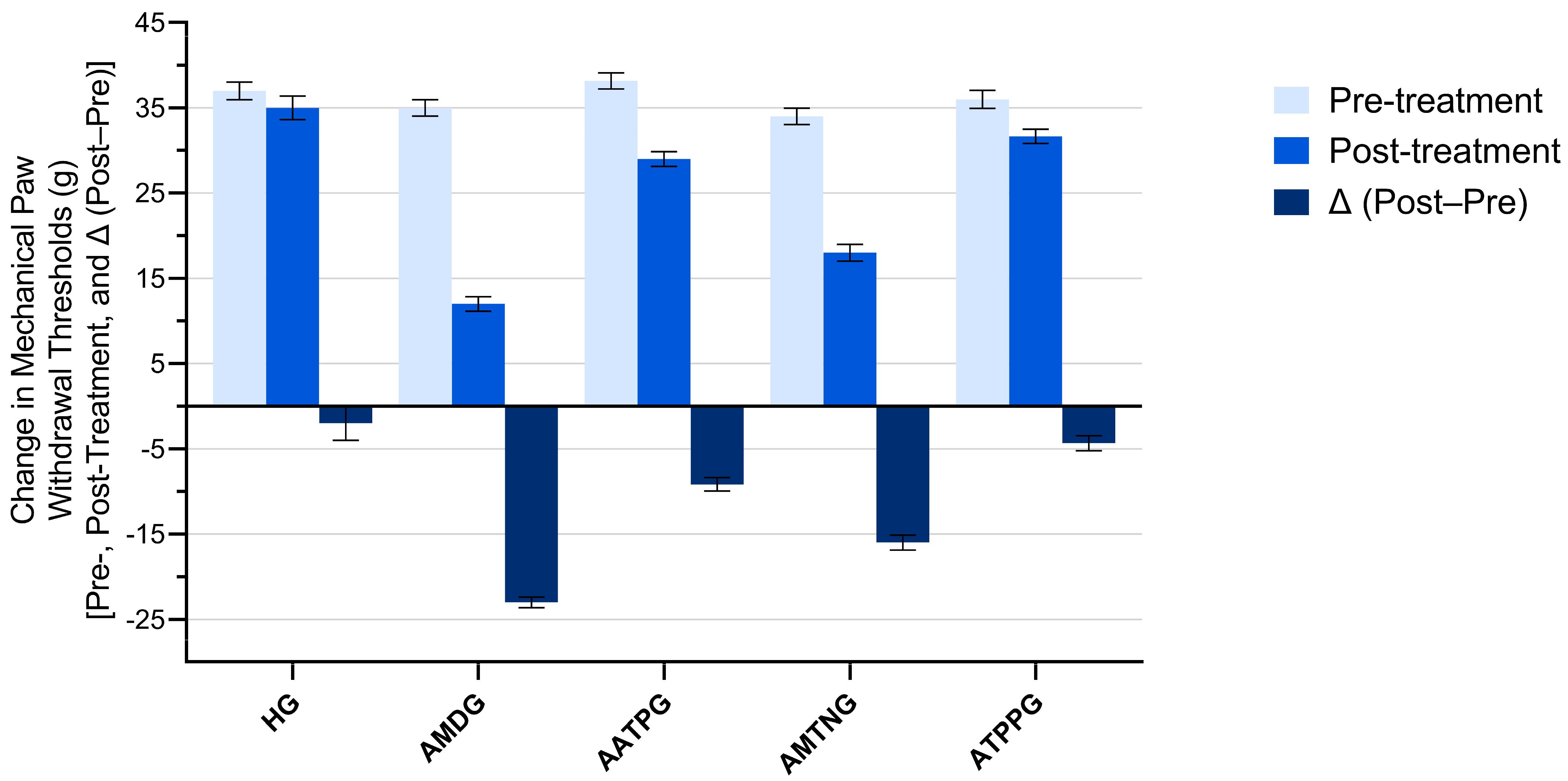

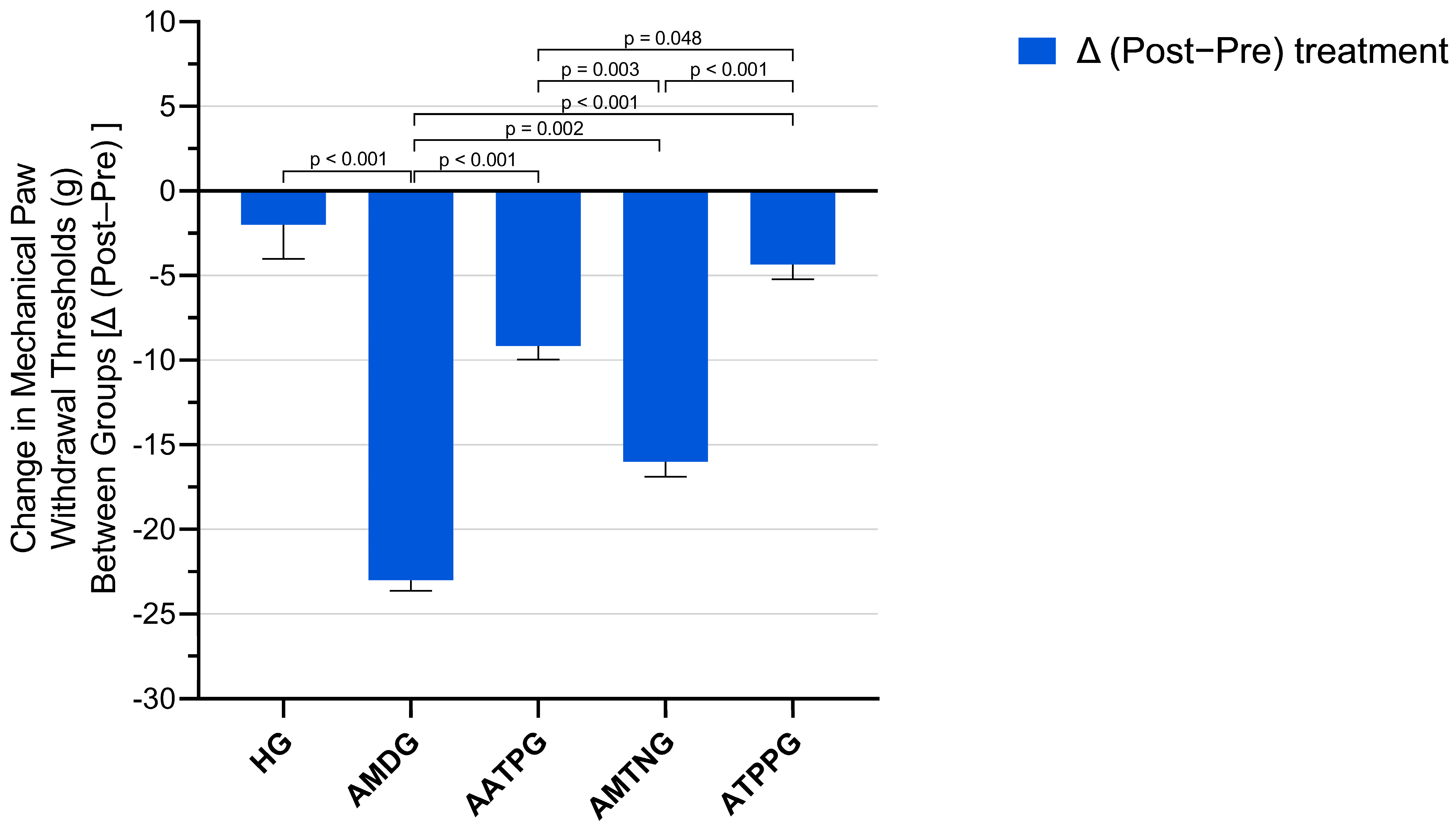

3.2. Paw Withdrawal Thresholds Findings

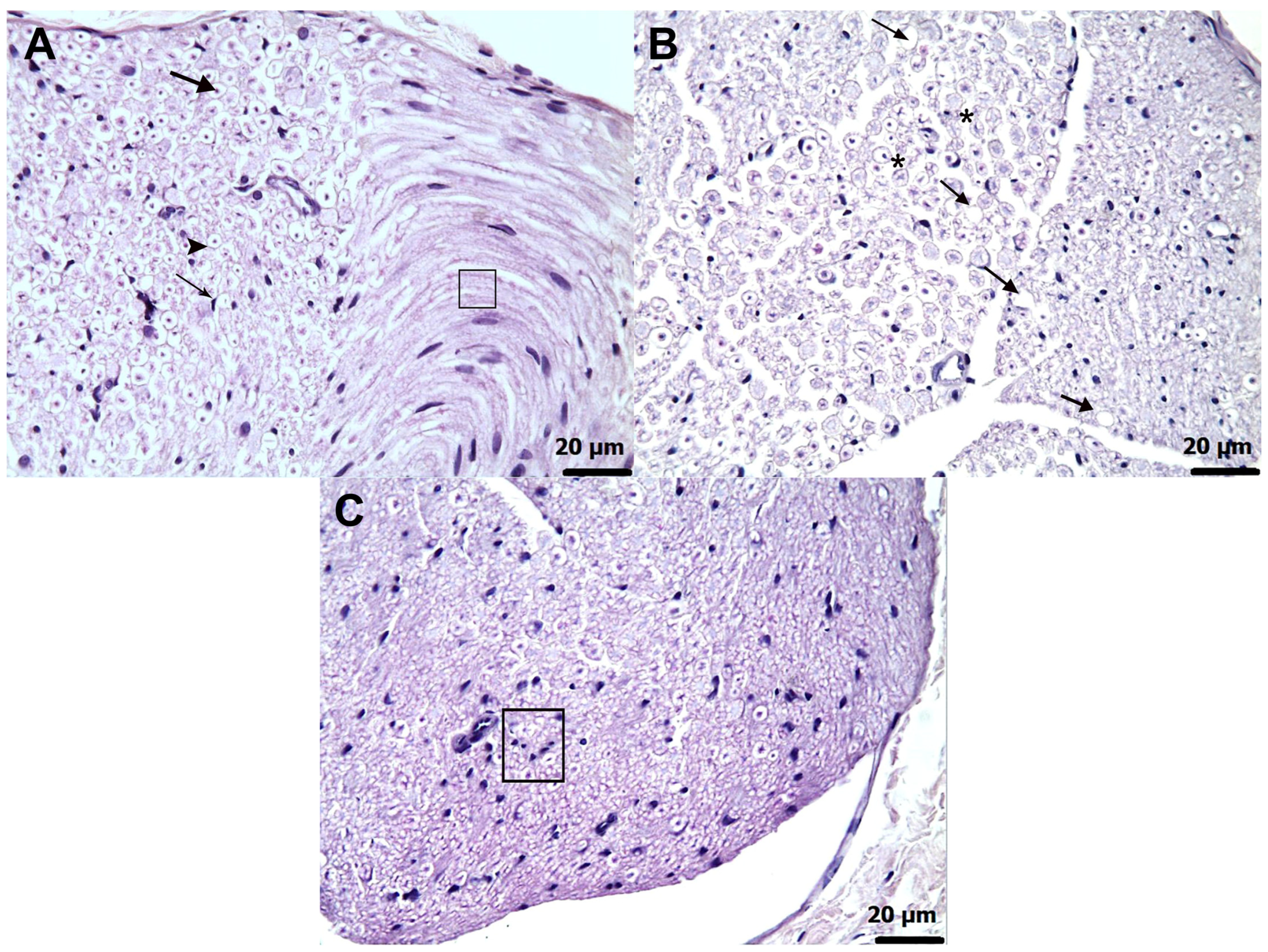

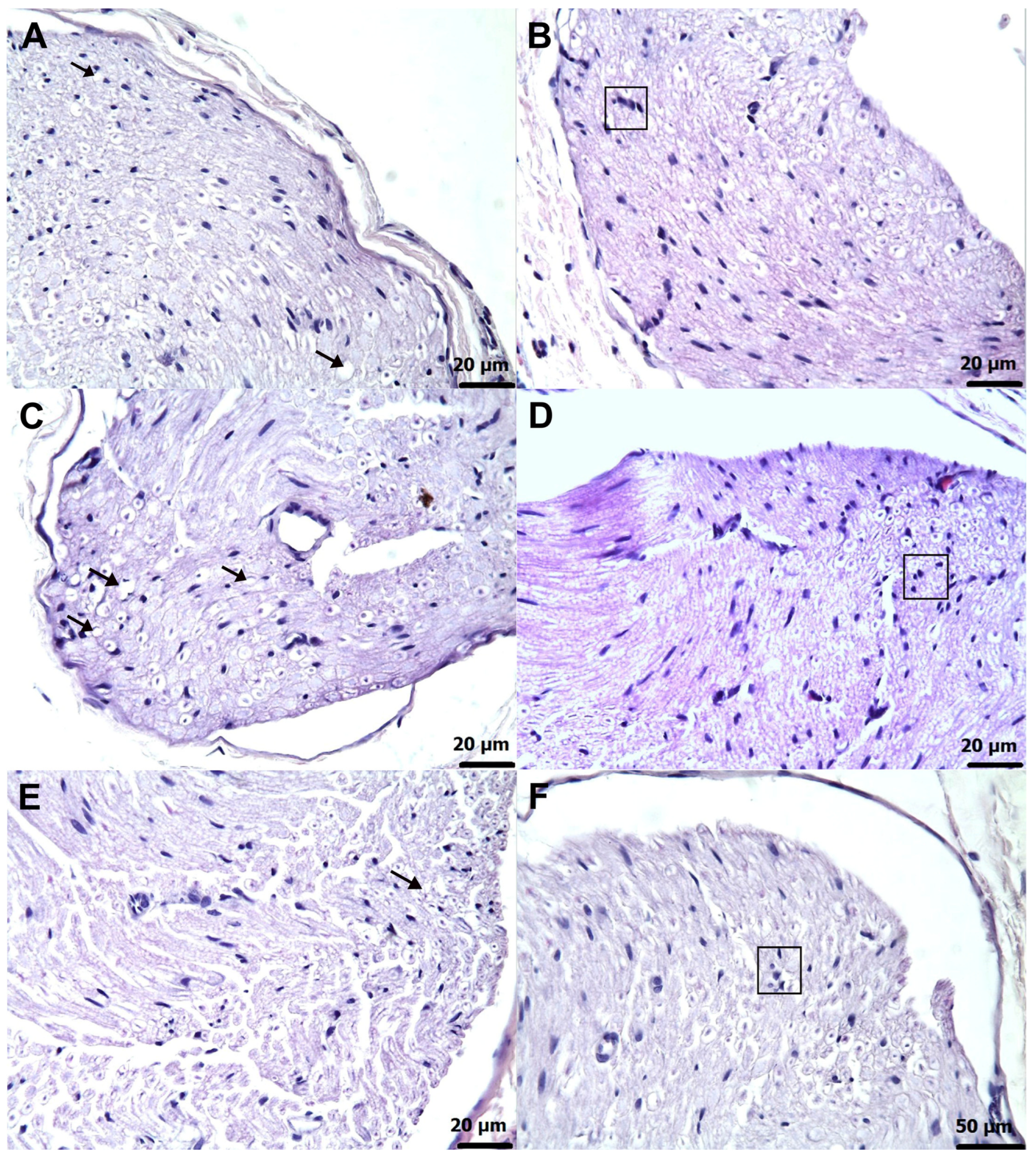

3.3. Histopathological Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HG | healthy group |

| AMDG | amiodarone alone group |

| AATPG | amiodarone + ATP group |

| AMTNG | amiodarone + melatonin group |

| ATPPG | amiodarone + TPP group |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| TPP | thiamine pyrophosphate |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| tGSH | total glutathione |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | catalase |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| IL-1β | interleukin one beta |

| IL-6 | interleukin six |

| Δ (post−pre) | Net change from baseline (post minus pre) |

References

- You, H.S.; Yoon, J.H.; Cho, S.B.; Choi, Y.D.; Kim, Y.H.; Choi, W.; Kang, H.C.; Choi, S.K. Amiodarone-Induced Multi-Systemic Toxicity Involving the Liver, Lungs, Thyroid, and Eyes: A Case Report. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 839441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling-Vannerus, T.; Skrubbeltrang, C.; Schjorring, O.L.; Moller, M.H.; Rasmussen, B.S. Acute amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity in adult ICU patients with new-onset atrial fibrillation-A systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2025, 69, e14535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serviddio, G.; Bellanti, F.; Giudetti, A.M.; Gnoni, G.V.; Capitanio, N.; Tamborra, R.; Romano, A.D.; Quinto, M.; Blonda, M.; Vendemiale, G.; et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and respiratory chain dysfunction account for liver toxicity during amiodarone but not dronedarone administration. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 2234–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Santos, L.F.; Stolfo, A.; Calloni, C.; Salvador, M. Catechin and epicatechin reduce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress induced by amiodarone in human lung fibroblasts. J. Arrhythm. 2017, 33, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betiu, A.M.; Chamkha, I.; Gustafsson, E.; Meijer, E.; Avram, V.F.; Asander Frostner, E.; Ehinger, J.K.; Petrescu, L.; Muntean, D.M.; Elmer, E. Cell-Permeable Succinate Rescues Mitochondrial Respiration in Cellular Models of Amiodarone Toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.S.; Kim, Y.N. Adverse effects of long-term amiodarone therapy. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bahri, L.; Bensied, A.; Nessnassi, M.; Fellat, I.; Cherti, M. Uncommon neuromyopathy toxicity induced by amiodarone therapy: Case report. Egypt. Heart J. 2025, 77, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.Y. Drug-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: Focus on Newer Offending Agents. J. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 6, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.R.; Urits, I.; Wolf, J.; Corrigan, D.; Colburn, L.; Peterson, E.; Williamson, A.; Viswanath, O. Drug-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy: A Narrative Review. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, S.; Aksakal, E.; Süleyman, H. Pathogenesis of Amiodarone-Related Toxicity. Arch. Basic Clin. Res. 2025, 7, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Marenco, R.; Estrada-Sanchez, I.A.; Medina-Escobedo, M.; Chim-Ake, R.; Lugo, R. The Effect of Oral Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Supplementation on Anaerobic Exercise in Healthy Resistance-Trained Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports 2024, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areti, A.; Yerra, V.G.; Komirishetty, P.; Kumar, A. Potential Therapeutic Benefits of Maintaining Mitochondrial Health in Peripheral Neuropathies. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuankaew, C.; Sawaddiruk, P.; Surinkaew, P.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Possible roles of mitochondrial dysfunction in neuropathy. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021, 131, 1019–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, T.T.; Schuch, V.; Hossack, D.J.; Chakraborty, R.; Johnson, E.L. Melatonin: The placental antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1339304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin: A Versatile Protector against Oxidative DNA Damage. Molecules 2018, 23, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuna-Castroviejo, D.; Escames, G.; Venegas, C.; Diaz-Casado, M.E.; Lima-Cabello, E.; Lopez, L.C.; Rosales-Corral, S.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Extrapineal melatonin: Sources, regulation, and potential functions. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2997–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J. Melatonin: Clinical relevance. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 17, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiong, Y.L.; Ng, K.Y.; Koh, R.Y.; Ponnudurai, G.; Chye, S.M. Melatonin Prevents Oxidative Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis in High Glucose-Treated Schwann Cells via Upregulation of Bcl2, NF-kappaB, mTOR, Wnt Signalling Pathways. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.; Samadi, M.; Baeeri, M.; Rahimifard, M.; Haghi-Aminjan, H. The neuroprotective effects of melatonin against diabetic neuropathy: A systematic review of non-clinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 984499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sawaf, E.S.; El Maraghy, N.N.; El-Abhar, H.S.; Zaki, H.F.; Zordoky, B.N.; Ahmed, K.A.; Abouquerin, N.; Mohamed, A.F. Melatonin mitigates vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy by inhibiting TNF-alpha/astrocytes/microglial cells activation in the spinal cord of rats, while preserving vincristine’s chemotherapeutic efficacy in lymphoma cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 492, 117134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, M.; Sajedi, F.; Mohammadi, Y.; Mehrpooya, M. Adjuvant use of melatonin for relieving symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy: Results of a randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 1649–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, T.; Yue, L.P.; Hu, L. Exogenous melatonin alleviates neuropathic pain-induced affective disorders by suppressing NF-kappaB/ NLRP3 pathway and apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeleszczuk, L.; Pisklak, D.M.; Grodner, B. Thiamine and Thiamine Pyrophosphate as Non-Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase-Experimental and Theoretical Investigations. Molecules 2025, 30, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shible, A.A.; Ramadurai, D.; Gergen, D.; Reynolds, P.M. Dry Beriberi Due to Thiamine Deficiency Associated with Peripheral Neuropathy and Wernicke’s Encephalopathy Mimicking Guillain-Barre syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am. J. Case Rep. 2019, 20, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, Z. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Deficiency (PDCD). Undergrad. Res. J. Hum. Sci. 2011, 10. Available online: https://publications.kon.org/urc/v10/rahim.html (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Ho, T.C.S.; Leeper, F.J. Open-chain thiamine analogues as potent inhibitors of thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP)-dependent enzymes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 6531–6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onk, D.; Mammadov, R.; Suleyman, B.; Cimen, F.K.; Cankaya, M.; Gul, V.; Altuner, D.; Senol, O.; Kadioglu, Y.; Malkoc, I.; et al. The effect of thiamine and its metabolites on peripheral neuropathic pain induced by cisplatin in rats. Exp. Anim. 2018, 67, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Pheby, D.; Henehan, G.; Brown, R.; Sieving, P.; Sykora, P.; Marks, R.; Falsini, B.; Capodicasa, N.; Miertus, S.; et al. Ethical considerations regarding animal experimentation. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E255–E266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadirci, E.; Suleyman, H.; Hacimuftuoglu, A.; Halici, Z.; Akcay, F. Indirect role of beta2-adrenergic receptors in the mechanism of analgesic action of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 38, 1860–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadogan, M.T.; Yavuzer, B.; Gursul, C.; Huseynova, G.; Yazici, G.N.; Gulaboglu, M.; Yilmaz, F.; Mendil, A.S.; Suleyman, H. Comparative study of the protective effects of adenosine triphosphate and resveratrol against amiodarone-induced potential liver damage and dysfunction in rats. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somuncu, A.M.; Parlak Somuncu, B.; Ozbay, A.D.; Cicek, I.; Suleyman, B.; Mammadov, R.; Bulut, S.; Bal Tastan, T.; Coban, T.A.; Suleyman, H.; et al. Potential effects of adenosine triphosphate and melatonin on oxidative and inflammatory optic nerve damage in rats caused by 5-fluorouracil. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 18, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinici, E.; Cetin, N.; Suleyman, B.; Altuner, D.; Yarali, O.; Balta, H.; Calik, I.; Tumkaya, L.; Suleyman, H. Gene expression and histopathological evaluation of thiamine pyrophosphate on optic neuropathy induced with ethambutol in rats. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1390–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrakceken, K.; Ucgul, R.K.; Coban, T.; Yazici, G.; Suleyman, H. Effect of adenosine triphosphate on amiodarone-induced optic neuropathy in rats: Biochemical and histopathological evaluation. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2023, 42, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goth, L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin. Chim. Acta 1991, 196, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Arizala, A.; Sobol, S.M.; McCarty, G.E.; Nichols, B.R.; Rakita, L. Amiodarone neuropathy. Neurology 1983, 33, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, E.P.; Harper, C.M.; St Louis, E.K.; Silber, M.H.; Josephs, K.A. Amiodarone-associated neuromyopathy: A report of four cases. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012, 19, e50–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Kuner, R.; Jensen, T.S. Neuropathic Pain: From Mechanisms to Treatment. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 259–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauermann, M.L.; Staff, N.P. Peripheral Neuropathy: A Review. JAMA 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathmanathan, A.; Cleary, L. Amiodarone-Associated Neurotoxicity. Am. J. Ther. 2021, 28, e165–e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, M.M.; Samii, L.; Leung, G.; Pearce, P. Amiodarone-induced neuromyopathy in a geriatric patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e236620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szychowski, K.A. Current State of Knowledge on Amiodarone (AMD)-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production in In Vitro and In Vivo Models. Oxygen 2025, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordiano, R.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Mangifesta, R.; Panzera, C.; Gangemi, S.; Minciullo, P.L. Malondialdehyde as a Potential Oxidative Stress Marker for Allergy-Oriented Diseases: An Update. Molecules 2023, 28, 5979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernyhough, P.; Huang, T.J.; Verkhratsky, A. Mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic sensory neuropathy. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2003, 8, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, N.; Papadopoulos, V. Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neuropathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitimus, D.M.; Popescu, M.R.; Voiculescu, S.E.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Pavel, B.; Zagrean, L.; Zagrean, A.M. Melatonin’s Impact on Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Reprogramming in Homeostasis and Disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Abreu, K.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Leal-Cardoso, J.H. Effects of Melatonin on Diabetic Neuropathy and Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekinci, B.; Suleyman, B.; Mammadov, R.; Cankaya, M.; Yazici, G.N.; Suleyman, Z.; Dal, C.N.; Ergul, E.E.; Onk, D.; Suleyman, H. The Effect of Thiamine Pyrophosphate and Tocilizumab Alone and in Combination upon Ethanol-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain in Rats. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2022, 41, 1618–1625. [Google Scholar]

- Goc, Z.; Szaroma, W.; Kapusta, E.; Dziubek, K. Protective effects of melatonin on the activity of SOD, CAT, GSH-Px and GSH content in organs of mice after administration of SNP. Chin. J. Physiol. 2017, 60, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alev-Tuzuner, B.; Oktay, S.; Turkyilmaz-Mutlu, I.B.; Kaya, S.; Akyuz, S.; Yanardag, R.; Yarat, A. Protective Effects of Vitamin U on Amiodarone-Induced Oxidative Stress and Altered Biomarkers in Rat Parotid Salivary Glands. Eurasian J. Vet. Sci. 2025, 41, e0445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazragi, R. Protective role of ferulic acid and/or gallic acid against pulmonary toxicity induced by amiodarone in rats. Arch. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Metwally, M.M.M.; Ebraheim, L.L.M.; Galal, A.A.A. Potential therapeutic role of melatonin on STZ-induced diabetic central neuropathy: A biochemical, histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Acta Histochem. 2018, 120, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, B.; Ates, I.; Yucel, N.; Suleyman, B.; Mendil, A.S.; Sezgin, E.T.; Suleyman, H. The Protective Effect of Thiamine and Thiamine Pyrophosphate Against Linezolid-Induced Oxidative Liver Damage and Lactic Acidosis in Rats. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeter, B.; Mammadov, R.; Koc, Z.; Bulut, S.; Tastan, T.B.; Gulaboglu, M.; Suleyman, H. Protective effects of thiamine pyrophosphate and cinnamon against oxidative liver damage induced by an isoniazid and rifampicin combination in rats. Investig. Clin. 2024, 65, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, G.; Selvarajah, D.; Tesfaye, S. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and clinical management of diabetic sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 400–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, R.A.; Zaki, M.S.A.; Al-Shraim, M.; Eldeen, M.A.; Haidara, M.A. Grape seed extract protects against amiodarone—Induced nephrotoxicity and ultrastructural alterations associated with the inhibition of biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in rats. Ultrastruct. Pathol. 2021, 45, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Tan, Z.; He, L.; Zhu, S.; Yan, R.; Kou, H.; Peng, J. Amiodarone promotes heat-induced apoptosis, inflammation and oxidative stress in mouse HL1 atrial myocytes. Nan Fang. Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2021, 41, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.K.; Lim, D.G. Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury with respect to oxidative stress and inflammatory response: A narrative review. J. Yeungnam Med. Sci. 2023, 40, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellissier, J.F.; Pouget, J.; Cros, D.; De Victor, B.; Serratrice, G.; Toga, M. Peripheral neuropathy induced by amiodarone chlorhydrate. A clinicopathological study. J. Neurol. Sci. 1984, 63, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okhovat, A.A.; Saffar, H.; Fatehi, F. Amiodarone-Induced Neuropathy with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy-like presentation. Neurol. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 8, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimi, N.; Yako, H.; Tsukamoto, M.; Takaku, S.; Yamauchi, J.; Kawakami, E.; Yanagisawa, H.; Watabe, K.; Utsunomiya, K.; Sango, K. Involvement of oxidative stress and impaired lysosomal degradation in amiodarone-induced schwannopathy. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2016, 44, 1723–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Xiao, W.H.; Bennett, G.J. Mitotoxicity and bortezomib-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 238, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Grade | Axonal Degeneration | Schwann Cell Proliferation (Focal Clusters of Adjacent Cells) | Interstitial Edema (% of Tissue Area) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | None | None | 0% |

| 1 | 1 axon | 1 focal cluster | <5% |

| 2 | 2–3 axons | 2–3 focal clusters | 6–15% |

| 3 | 4–5 axons | 4–5 focal clusters | 16–25% |

| 4 | ≥6 axons | ≥6 focal clusters | ≥26% |

| Post hoc Test p-Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group Comparisons | MDA * | tGSH ** | SOD * | CAT * | TNF-α * | IL-1β * | IL-6 ** |

| HG vs. AMDG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HG vs. AATPG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HG vs. AMTNG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HG vs. ATPPG | 0.149 | 0.242 | 0.512 | 0.360 | 0.772 | 0.643 | 0.349 |

| AMDG vs. AATPG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AMDG vs. AMTNG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AMDG vs. ATPPG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AATPG vs. AMTNG | <0.001 | 0.013 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AATPG vs. ATPPG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| AMTNG vs. ATPPG | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| F value | 346.018 | 286.043 a | 295.187 | 174.922 | 135.431 | 118.787 | 241.618 a |

| df (df1/df2) | 4/25 | 4/11.377 b | 4/25 | 4/25 | 4/25 | 4/25 | 4/12.223 b |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Paw Withdrawal Thresholds (g) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | n | Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | Δ (Post−Pre) | Shapiro–Wilk Pre-Treatment p Values | Shapiro–Wilk Post-Treatment p Values | t | p (Two-Tailed) | Cohen’s dz |

| HG | 6 | 37.00 ± 1.03 | 35.00 ± 1.37 | −2.00 ± 2.02 | 0.757 | 0.886 | −0.992 | 0.367 | −0.405 |

| AMDG | 6 | 35.00 ± 0.97 | 12.00 ± 0.86 | −23.00 ± 0.63 | 0.739 | 0.320 | −36.366 | <0.001 | −14.846 |

| AATPG | 6 | 38.17 ± 0.95 | 29.00 ± 0.86 | −9.17 ± 0.79 | 0.287 | 0.320 | −11.569 | <0.001 | −4.723 |

| AMTNG | 6 | 34.00 ± 0.97 | 18.00 ± 0.97 | −16.00 ± 0.89 | 0.739 | 0.739 | −17.889 | <0.001 | −7.303 |

| ATPPG | 6 | 36.00 ± 1.07 | 31.67 ± 0.84 | −4.33 ± 0.88 | 0.817 | 0.493 | −4.914 | 0.004 | −2.006 |

| Paw Withdrawal Thresholds (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Pre-Treatment | Post-Treatment | Δ (Post−Pre) | Shapiro–Wilk Pre-Treatment p-Value | Shapiro–Wilk Post-Treatment p-Value | Shapiro–Wilk Δ (Post−Pre) p-Value | Analgesic Activity (%) |

| HG | 37.00 ± 1.03 | 35.00 ± 1.37 | −2.00 ± 2.02 | 0.757 | 0.886 | 0.864 | 91.30 |

| AMDG | 35.00 ± 0.97 | 12.00 ± 0.86 | −23.00 ± 0.63 | 0.739 | 0.320 | 0.456 | - |

| AATPG | 38.17 ± 0.95 | 29.00 ± 0.86 | −9.17 ± 0.79 | 0.287 | 0.320 | 0.452 | 60.13 |

| AMTNG | 34.00 ± 0.97 | 18.00 ± 0.97 | −16.00 ± 0.89 | 0.739 | 0.739 | 0.783 | 30.43 |

| ATPPG | 36.00 ± 1.07 | 31.67 ± 0.84 | −4.33 ± 0.88 | 0.817 | 0.493 | 0.405 | 81.17 |

| Group comparisons | Pre-treatment p value | Post-treatment p value | Δ (post−pre) p-value | ||||

| HG vs. AMDG | 0.621 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| HG vs. AATPG | 0.919 | 0.002 | 0.002 | ||||

| HG vs. AMTNG | 0.239 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| HG vs. ATPPG | 0.952 | 0.159 | 0.616 | ||||

| AMDG vs. AATPG | 0.195 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| AMDG vs. AMTNG | 0.952 | 0.002 | 0.002 | ||||

| AMDG vs. ATPPG | 0.952 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| AATPG vs. AMTNG | 0.048 | <0.001 | 0.003 | ||||

| AATPG vs. ATPPG | 0.549 | 0.348 | 0.048 | ||||

| AMTNG vs. ATPPG | 0.621 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| F | 2.693 | 95.011 | 55.783 | ||||

| df (df1/df2) | 4/25 | 4/25 | 4/25 | ||||

| significance | 0.054 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Histopathological Grading Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Axonal Degeneration | Proliferation in Schwann Cells | Interstitial Edema |

| HG | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) |

| AMDG | 4.00 (3.00–4.00) | 4.00 (3.00–4.00) | 3.50 (3.00–4.00) |

| AATPG | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) |

| AMTNG | 2.50 (2.00–3.00) | 3.00 (2.00–3.00) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) |

| ATPPG | 1.00 (0.00–2.00) | 1.00 (0.00–2.00) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) |

| Group comparisons | p-values | ||

| HG vs. AMDG | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| HG vs. AATPG | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.138 |

| HG vs. AMTNG | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.138 |

| HG vs. ATPPG | 0.021 | 0.006 | 0.317 |

| AMDG vs. AATPG | 0.007 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| AMDG vs. AMTNG | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| AMDG vs. ATPPG | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| AATPG vs. AMTNG | 0.423 | 0.057 | 1.000 |

| AATPG vs. ATPPG | 0.020 | 0.067 | 0.523 |

| AMTNG vs. ATPPG | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.523 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kahramanlar, A.A.; Ozgodek, H.B.; Ince, R.; Yavuzer, B.; Admis, O.; Mendil, A.S.; Ekinci, B.; Suleyman, H. Comparative Investigation of the Effects of Adenosine Triphosphate, Melatonin, and Thiamine Pyrophosphate on Amiodarone-Induced Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain in Male Rats. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122965

Kahramanlar AA, Ozgodek HB, Ince R, Yavuzer B, Admis O, Mendil AS, Ekinci B, Suleyman H. Comparative Investigation of the Effects of Adenosine Triphosphate, Melatonin, and Thiamine Pyrophosphate on Amiodarone-Induced Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain in Male Rats. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122965

Chicago/Turabian StyleKahramanlar, Agah Abdullah, Habip Burak Ozgodek, Ramazan Ince, Bulent Yavuzer, Ozlem Admis, Ali Sefa Mendil, Bilge Ekinci, and Halis Suleyman. 2025. "Comparative Investigation of the Effects of Adenosine Triphosphate, Melatonin, and Thiamine Pyrophosphate on Amiodarone-Induced Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain in Male Rats" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122965

APA StyleKahramanlar, A. A., Ozgodek, H. B., Ince, R., Yavuzer, B., Admis, O., Mendil, A. S., Ekinci, B., & Suleyman, H. (2025). Comparative Investigation of the Effects of Adenosine Triphosphate, Melatonin, and Thiamine Pyrophosphate on Amiodarone-Induced Neuropathy and Neuropathic Pain in Male Rats. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2965. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122965