piR-hsa-022095 Drives Hypertrophic Scar Formation via KLF11-Dependent Fibroblast Proliferation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Acquisition and Ethical Clearance

2.2. Primary Skin Fibroblasts Isolation and Culture

2.3. Cell Transfection

2.4. Cell Viability Analysis

2.5. Cell Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Analysis

2.6. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Western Blot

2.8. Double Luciferase Reporter Analysis

2.9. Cell Motility Assays

2.10. Scratch Wound-Healing Assay

2.11. mRNA and piRNA Sequencing with Bioinformatic Analysis

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dynamic Expression Landscape of piRNAs in HS Pathogenesis

3.2. Inhibition of piR-hsa-022095 Suppresses Fibroblast Proliferation and Motility While Inducing Apoptosis

3.3. piR-hsa-022095 Regulates a Network of Cell-Cycle–Associated Genes

3.4. KLF11 Is the Molecular Target of piR-hsa-022095

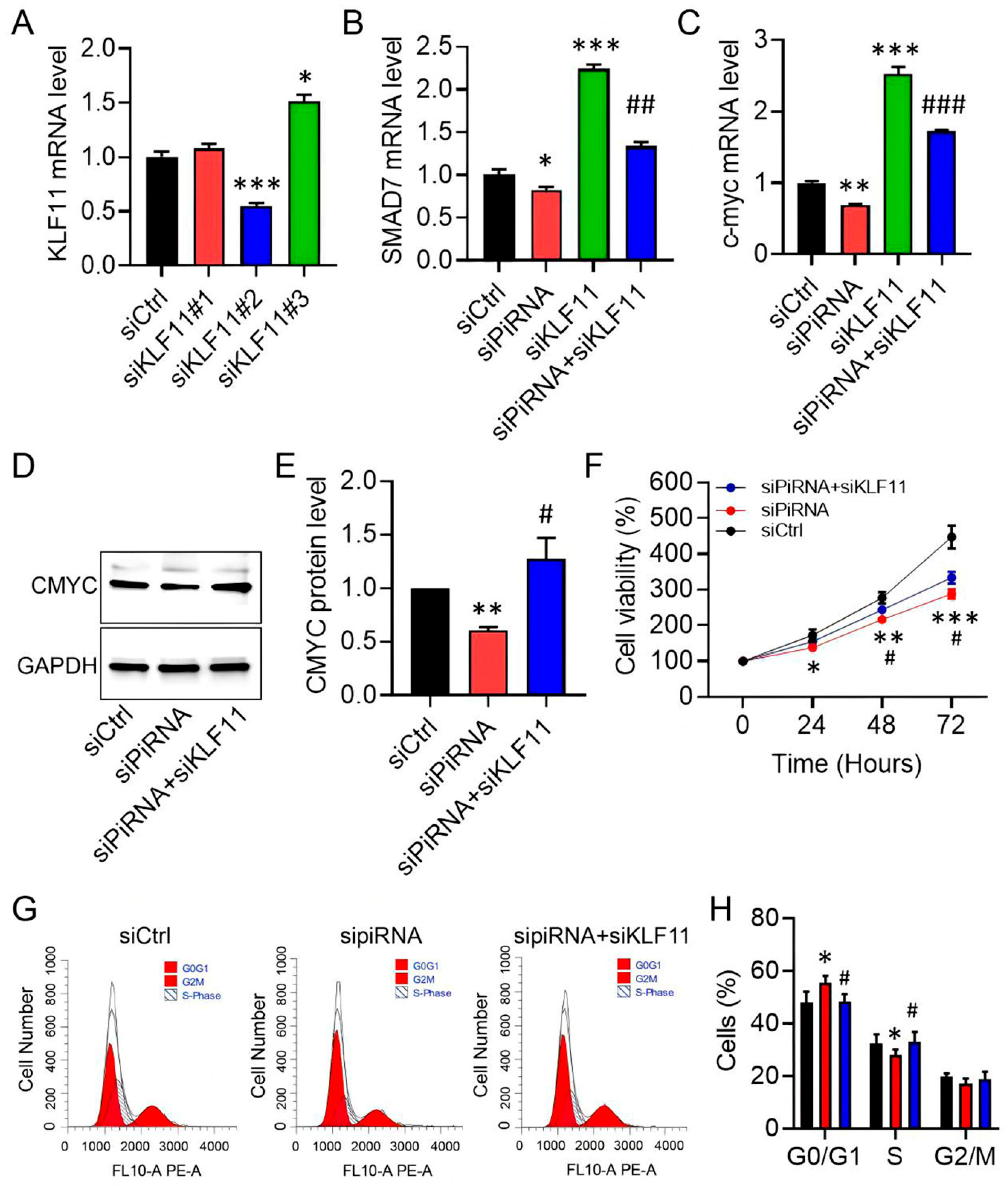

3.5. KLF11 Restoration Reverses piR-hsa-022095–Induced Fibroblast Activation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HS | Hypertrophic scar |

| piRNAs | PIWI-interacting RNAs |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

References

- Mari, W.; Alsabri, S.G.; Tabal, N.; Younes, S.; Sherif, A.; Simman, R. Novel Insights on Understanding of Keloid Scar: Article Review. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Wound Spec. 2015, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerty, C.C.; Jeschke, M.G.; Branski, L.K.; Barret, J.P.; Dziewulski, P.; Herndon, D.N. Hypertrophic scarring: The greatest unmet challenge after burn injury. Lancet 2016, 388, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W. Management of keloid scars: Noninvasive and invasive treatments. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2021, 48, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Han, J. Non-coding RNAs in hypertrophic scars and keloids: Current research and clinical relevance: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 128334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Farah, K.; Millis, R.M. Epigenetic Influences on Wound Healing and Hypertrophic-Keloid Scarring: A Review for Basic Scientists and Clinicians. Cureus 2022, 14, e23503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irma, J.; Kartasasmita, A.S.; Kartiwa, A.; Irfani, I.; Rizki, S.A.; Onasis, S. From Growth Factors to Structure: PDGF and TGF-β in Granulation Tissue Formation. A Literature Review. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Kong, H.; Qi, D.; Qiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Wang, H.; He, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.; et al. Epidermal stem cell derived exosomes-induced dedifferentiation of myofibroblasts inhibits scarring via the miR-203a-3p/PIK3CA axis. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhu, S.; Xiong, J.; Hu, F.; Liang, X.; Ye, X. Fibroblast growth factor 21 alleviates idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis by inhibiting PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling and stimulating autophagy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 132896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzik, J.; Czechowicz, P.; Wiech-Walow, A.; Slawski, J.; Collawn, J.F.; Bartoszewski, R. PiRNAs, PiRNA-Like, and PIWI Proteins in Somatic Cells: From Genetic Regulation to Disease Mechanisms. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2025, 16, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, W.; Liu, N.; Toiyama, Y.; Kusunoki, M.; Nagasaka, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Wei, Q.; Qin, H.; Lin, H.; Ma, Y.; et al. Novel evidence for a PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNA) as an oncogenic mediator of disease progression, and a potential prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Fang, B.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, S. piRNA, the hidden player in cardiac fibrosis: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennakesavan, K.; Haorah, J.; Samikkannu, T. piRNA/PIWI pathways and epigenetic crosstalk in human diseases: Molecular insights into HIV-1 infection and drugs of abuse. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2025, 36, 102473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour, M.; Saeidi, K.; Ferdosi, F.; Khanifar, H.; Dadgostar, E.; Zakizadeh, F.; Abdolghaderi, S.; Khatami, S.H. Non-coding RNA biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 576, 120427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhu, P.; Magotra, A.; Sindhu, V.; Chaudhary, P. Unravelling the impact of epigenetic mechanisms on offspring growth, production, reproduction and disease susceptibility. Zygote 2024, 32, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, S.A.; Gardini, A. Genomic regulation of transcription and RNA processing by the multitasking Integrator complex. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.; Yuan, K.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Dong, X.; Sheng, S.; Liu, M.; et al. PiRNA CFAPIR inhibits cardiac fibrosis by regulating the muscleblind-like protein MBNL2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivam, P.; Ball, D.; Cooley, A.; Osi, I.; Rayford, K.J.; Gonzalez, S.B.; Edwards, A.D.; McIntosh, A.R.; Devaughn, J.; Pugh-Brown, J.P.; et al. Regulatory roles of PIWI-interacting RNAs in cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2025, 328, H991–H1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, H.; Xu, X.; Deng, C.C.; Yang, B. Isolation, Culture, and Characterization of Primary Dermal Fibroblasts from Human Keloid Tissue. J. Vis. Exp. 2023, 197, e65153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ning, J.; Okon, I.; Zheng, X.; Satyanarayana, G.; Song, P.; Xu, S.; Zou, M.H. Suppression of m6A mRNA modification by DNA hypermethylated ALKBH5 aggravates the oncological behavior of KRAS mutation/LKB1 loss lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, R. Dynamics of Transposable Element Invasions with piRNA Clusters. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, B.; Munafo, M.; Ciabrelli, F.; Eastwood, E.L.; Fabry, M.H.; Kneuss, E.; Hannon, G.J. piRNA-Guided Genome Defense: From Biogenesis to Silencing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Li, Q.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Gong, Z.; Deng, H.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, M.; Li, X.; Li, G.; et al. TSC22D2 interacts with PKM2 and inhibits cell growth in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; Hester, A. The Distinct Roles of Transcriptional Factor KLF11 in Normal Cell Growth Regulation and Cancer as a Mediator of TGF-β Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, R.; Sha, C.; Xie, Q.; Yao, D.; Yao, M. Alterations of Krüppel-like Factor Signaling and Potential Targeted Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Liao, T.; Xie, J.; Kang, D.; He, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Miao, X.; Yan, Y.; et al. The burgeoning importance of PIWI-interacting RNAs in cancer progression. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Borja, E.; Siegl, F.; Mateu, R.; Slaby, O.; Sedo, A.; Busek, P.; Sana, J. Critical appraisal of the piRNA-PIWI axis in cancer and cancer stem cells. Biomark. Res. 2024, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritam, S.; Signor, S. Evolution of piRNA-guided defense against transposable elements. Trends Genet. 2025, 41, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gou, L.T.; Liu, M.F. Noncanonical functions of PIWIL1/piRNAs in animal male germ cells and human diseasesdagger. Biol. Reprod. 2022, 107, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.Z.; Gavriilidis, G.; Asano, H.; Stamatoyannopoulos, G. Functional study of transcription factor KLF11 by targeted gene inactivation. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2005, 34, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-β signaling in health, disease, and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, X.F.; Wang, Z.C.; Lou, D.; Fang, Q.Q.; Hu, Y.Y.; Zhao, W.Y.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wu, L.H.; Tan, W.Q. Current potential therapeutic strategies targeting the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway to attenuate keloid and hypertrophic scar formation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, Q.; Lv, X.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Fu, X.; et al. Using network pharmacology to discover potential drugs for hypertrophic scars. Br. J. Dermatol. 2024, 191, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohla, G.; Krieglstein, K.; Spittau, B. Tieg3/Klf11 induces apoptosis in OLI-neu cells and enhances the TGF-β signaling pathway by transcriptional repression of Smad7. J. Cell Biochem. 2008, 104, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, J.; Jones, T.L.; Sun, Z.; Chanana, P.; Jaiswal, I.; Leontovich, A.; Carapanceanu, N.; Carapanceanu, V.; Saadalla, A.; Osman, A.; et al. Corrigendum to “Host immunity and KLF 11 deficiency together promote fibrosis in a mouse model of endometriosis” [BBA—Mol. Basis of Dis. 1869 (2023) 166784]. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 166923, Erratum in: Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellenrieder, V.; Buck, A.; Harth, A.; Jungert, K.; Buchholz, M.; Adler, G.; Urrutia, R.; Gress, T.M. KLF11 mediates a critical mechanism in TGF-β signaling that is inactivated by Erk-MAPK in pancreatic cancer cells. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, R.; Qian, W.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Xiao, Y.; Lin, Y. piR-hsa-022095 Drives Hypertrophic Scar Formation via KLF11-Dependent Fibroblast Proliferation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122963

Ren R, Qian W, Zhao H, Wang D, Xiao Y, Lin Y. piR-hsa-022095 Drives Hypertrophic Scar Formation via KLF11-Dependent Fibroblast Proliferation. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122963

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Rongxin, Wenjiang Qian, Hongyi Zhao, Di Wang, Yanxia Xiao, and Yajun Lin. 2025. "piR-hsa-022095 Drives Hypertrophic Scar Formation via KLF11-Dependent Fibroblast Proliferation" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122963

APA StyleRen, R., Qian, W., Zhao, H., Wang, D., Xiao, Y., & Lin, Y. (2025). piR-hsa-022095 Drives Hypertrophic Scar Formation via KLF11-Dependent Fibroblast Proliferation. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122963