Comparative Outcomes of Direct Versus Connector-Assisted Peripheral Nerve Repair

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Outcomes

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

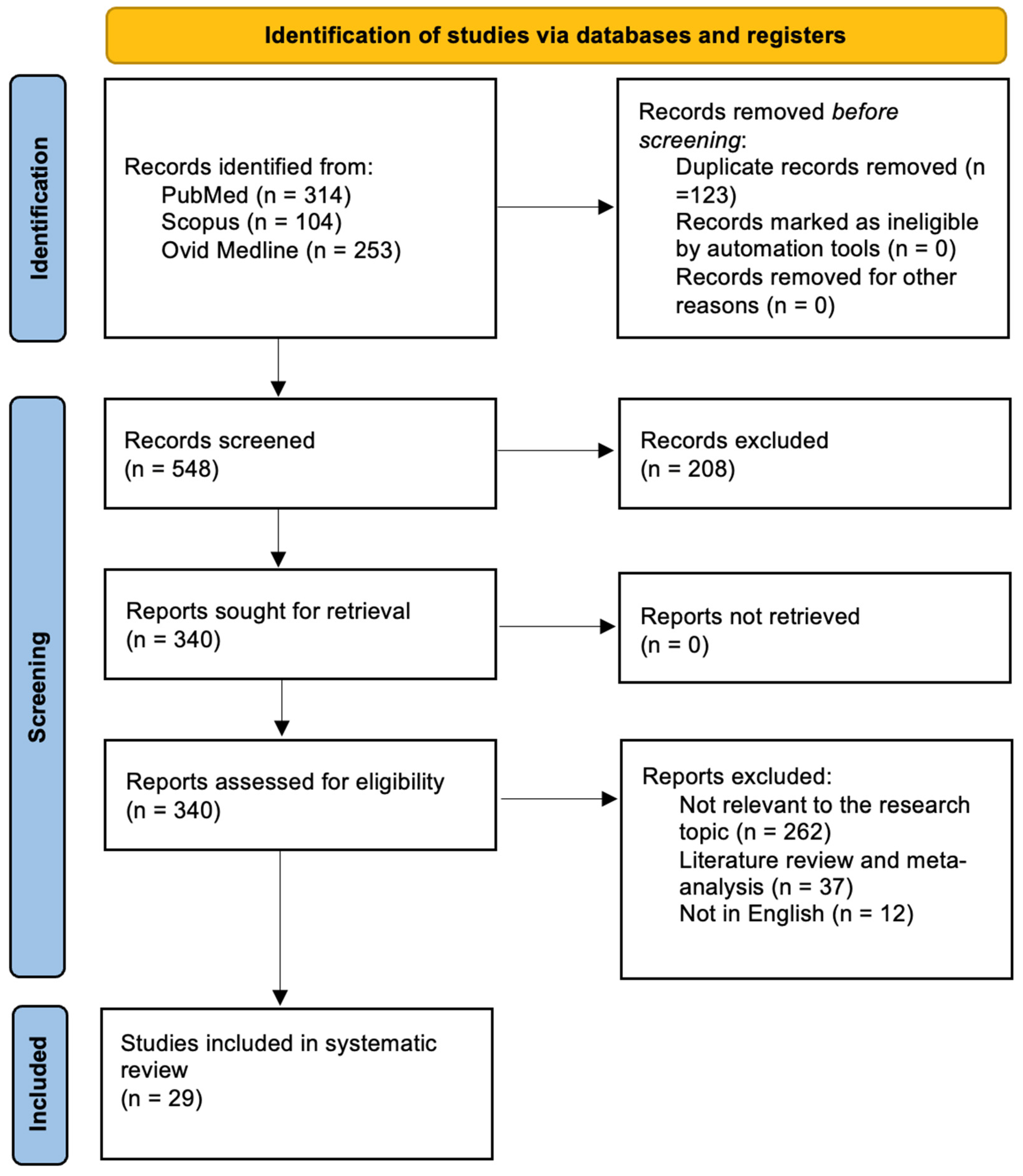

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages and Limitations of Direct Repair

4.2. The Promise of Connector-Assisted Repair

4.3. Interpreting Sensory and Motor Outcomes

4.4. Complication Profiles and Patient-Reported Outcomes

4.5. Future Prospects

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PNIs | Peripheral nerve injuries |

| DASH | The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand outcome questionnaire |

| DR | Direct repair |

| CAR | Connector-assisted repair |

| MR | Meaningful recovery |

| MRCC | Medical Research Council Classification |

| SWMF | Semmes–Weinstein monofilament |

| S2PD | static two-point discrimination |

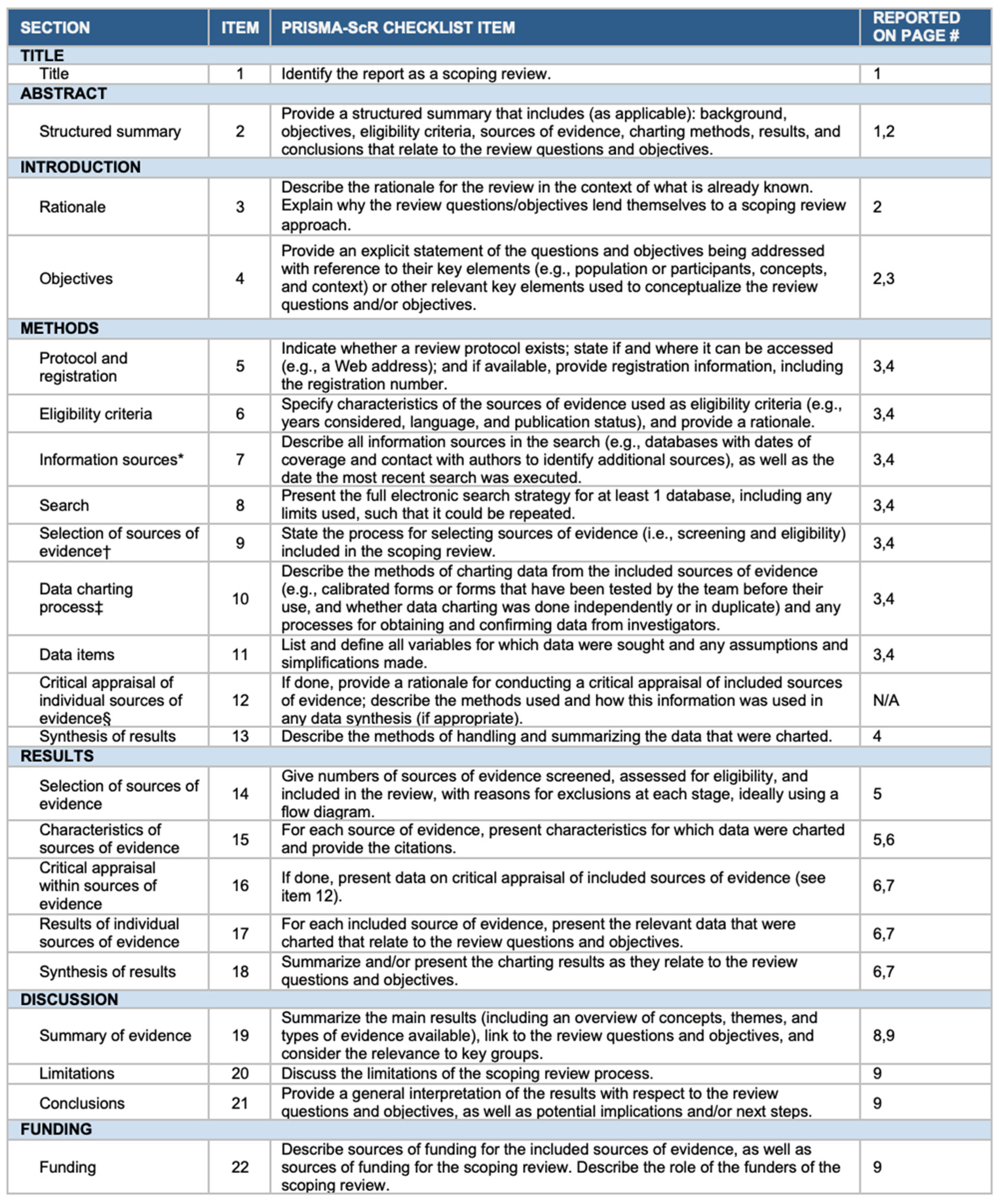

Appendix A. The PRISMA-ScR Checklist

References

- Selecki, B.R.; Ring, I.T.; Simpson, D.A.; Vanderfield, G.K.; Sewell, M.F. Trauma to the central and peripheral nervous systems. Part II: A statistical profile of surgical treatment New South Wales 1977. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1982, 52, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, J.; Munro, C.A.; Prasad, V.S.; Midha, R. Analysis of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve injuries in a population of patients with multiple injuries. J. Trauma. 1998, 45, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsy, M.; Watkins, R.; Jensen, M.R.; Guan, J.; Brock, A.A.; Mahan, M.A. Trends and Cost Analysis of Upper Extremity Nerve Injury Using the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample. World Neurosurg. 2019, 123, e488–e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtkiewicz, D.M.; Saunders, J.; Domeshek, L.; Novak, C.B.; Kaskutas, V.; Mackinnon, S.E. Social impact of peripheral nerve injuries. Hand 2015, 10, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauch, J.T.; Bae, A.; Shubinets, V.; Lin, I.C. A Systematic Review of Sensory Outcomes of Digital Nerve Gap Reconstruction With Autograft, Allograft, and Conduit. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2019, 82, S247–S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, A.W. Enhancing axon regeneration in peripheral nerves also increases functionally inappropriate reinnervation of targets. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005, 490, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.A.; Nydick, J.; Leversedge, F.; Power, D.; Styron, J.; Safa, B.; Buncke, G. Clinical Outcomes of Symptomatic Neuroma Resection and Reconstruction with Processed Nerve Allograft. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltán, R.; Klíma, K.; Špačková, J.; Šedý, J. Mechanism of traumatic neuroma development. Med. Hypotheses 2008, 71, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.L.; Trumble, T.E.; Swiontkowski, M.F.; Tencer, A.F. Nerve tension and blood flow in a rat model of immediate and delayed repairs. J. Hand Surg. 1992, 17, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacs, J.; Safa, B.; Evans, P.J.; Greenberg, J. Technical Assessment of Connector-Assisted Nerve Repair. J. Hand Surg. 2016, 41, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wei, H.; Zhu, H. Nerve wrap after end-to-end and tension-free neurorrhaphy attenuates neuropathic pain: A prospective study based on cohorts of digit replantation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battiston, B.; Geuna, S.; Ferrero, M.; Tos, P. Nerve repair by means of tubulization: Literature review and personal clinical experience comparing biological and synthetic conduits for sensory nerve repair. Microsurgery 2005, 25, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.J.; Bain, J.R.; Mackinnon, S.E.; Makino, A.P.; Hunter, D.A. Selective reinnervation: A comparison of recovery following microsuture and conduit nerve repair. Brain Res. 1991, 559, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 29, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellon, A.L.; Curtis, R.M.; Edgerton, M.T. Reeducation of sensation in the hand after nerve injury and repair. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1974, 53, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sunitha, M.; Chung, K.C. How to measure outcomes of peripheral nerve surgery. Hand Clin. 2013, 29, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.Z.; Crain, G.M.; Baylis, W.; Tsai, T.M. Outcome of digital nerve injuries in adults. J. Hand Surg. 1996, 21, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, R.A.; Breidenbach, W.C.; Brown, R.E.; Jabaley, M.E.; Mass, D.P. A randomized prospective study of polyglycolic acid conduits for digital nerve reconstruction in humans. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2000, 106, 1036–1045; discussion 1046–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundborg, G.; Rosén, B.; Dahlin, L.; Holmberg, J.; Rosén, I. Tubular repair of the median or ulnar nerve in the human forearm: A 5-year follow-up. J. Hand Surg. 2004, 29, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertleff, M.J.O.E.; Meek, M.F.; Nicolai, J.P.A. A prospective clinical evaluation of biodegradable neurolac nerve guides for sensory nerve repair in the hand. J. Hand Surg. 2005, 30, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberg, M.; Ljungberg, C.; Edin, E.; Millqvist, H.; Nordh, E.; Theorin, A.; Terenghi, G.; Wiberg, M. Clinical evaluation of a resorbable wrap-around implant as an alternative to nerve repair: A prospective, assessor-blinded, randomised clinical study of sensory, motor and functional recovery after peripheral nerve repair. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2009, 62, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiaco, S.; Tos, P.; Conforti, L.G.; Geuna, S.; Battiston, B. Termino-lateral nerve suture in lesions of the digital nerves: Clinical experience and literature review. J. Hand Surg. (Eur. Vol.) 2010, 35, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckstyns, M.E.; Sørensen, A.I.; Viñeta, J.F.; Rosén, B.; Navarro, X.; Archibald, S.J.; Valss-Solé, J.; Moldovan, M.; Krarup, C. Collagen conduit versus microsurgical neurorrhaphy: 2-year follow-up of a prospective, blinded clinical and electrophysiological multicenter randomized, controlled trial. J. Hand Surg. 2013, 38, 2405–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basar, H.; Basar, B.; Erol, B.; Tetik, C. Comparison of ulnar nerve repair according to injury level and type. Int. Orthop. 2014, 38, 2123–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andelkovic, S.Z.; Lesic, A.R.; Bumbasirevic, M.Z.; Rasulic, L.G. The Outcomes of 150 Consecutive Patients with Digital Nerve Injuries Treated in a Single Center. Turk. Neurosurg. 2017, 27, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bulut, T.; Akgün, U.; Çıtlak, A.; Aslan, C.; Şener, U.; Şener, M. Prognostic factors in sensory recovery after digital nerve repair. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2016, 50, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakin, R.M.; Calcagni, M.; Klein, H.J.; Giovanoli, P. Long-term clinical outcome after epineural coaptation of digital nerves. J. Hand Surg. (Eur. Vol.) 2016, 41, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruç, M.; Ozer, K.; Çolak, Ö.; Kankaya, Y.; Koçer, U. Does crossover innervation really affect the clinical outcome? A comparison of outcome between unilateral and bilateral digital nerve repair. Neural Regen. Res. 2016, 11, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.L.; Maier, C.; Mainka, T.; Mannil, L.; Vollert, J.; Homann, H.H. Recovery of mechanical detection thresholds after direct digital nerve repair versus conduit implantation. J. Hand Surg. (Eur. Vol.) 2017, 42, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böcker, A.; Aman, M.; Kneser, U.; Harhaus, L.; Siemers, F.; Stang, F. Closing the Gap: Bridging Peripheral Sensory Nerve Defects with a Chitosan-Based Conduit a Randomized Prospective Clinical Trial. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleurette, J.; Gaume, M.; De Tienda, M.; Dana, C.; Pannier, S. Peripheral nerve injuries of the upper extremity in a pediatric population: Outcomes and prognostic factors. Hand Surg. Rehabil. 2022, 41, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, Y.; Morimoto, S.; Takakura, Y.; Nakamura, T. Regeneration of Peripheral Nerve Gaps with a Polyglycolic Acid-Collagen Tube. Neurosurgery 2004, 55, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, J.S.; Jacoby, S.M. Repair of lacerated peripheral nerves with nerve conduits. Tech. Hand Up. Extrem. Surg. 2008, 12, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, B.D.; McWilliams, A.D.; Whitener, G.B.; Messer, T.M. Early clinical experience with collagen nerve tubes in digital nerve repair. J. Hand Surg. 2008, 33, 1081–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangensteen, K.J.; Kalliainen, L.K. Collagen tube conduits in peripheral nerve repair: A retrospective analysis. Hand 2010, 5, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, J.S.; Jacoby, S.M.; Lincoski, C.J. Reconstruction of digital nerves with collagen conduits. J. Hand Surg. 2011, 36, 1441–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiriac, S.; Facca, S.; Diaconu, M.; Gouzou, S.; Liverneaux, P. Experience of using the bioresorbable copolyester poly(DL-lactide-ε-caprolactone) nerve conduit guide NeurolacTM for nerve repair in peripheral nerve defects: Report on a series of 28 lesions. J. Hand Surg. (Eur. Vol.) 2012, 37, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tos, P.; Battiston, B.; Ciclamini, D.; Geuna, S.; Artiaco, S. Primary repair of crush nerve injuries by means of biological tubulization with muscle-vein-combined grafts. Microsurgery 2012, 32, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Means, K.R.J.; Rinker, B.D.; Higgins, J.P.; Payne, S.H.J.; Merrell, G.A.; Wilgis, E.F.S. A Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized, Pilot Study of Outcomes for Digital Nerve Repair in the Hand Using Hollow Conduit Compared with Processed Allograft Nerve. Hand 2016, 11, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuhara, H.; Hirase, Y.; Isogai, N.; Sueyoshi, Y. A clinical multi-center registry study on digital nerve repair using a biodegradable nerve conduit of PGA with external and internal collagen scaffolding. Microsurgery 2019, 39, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rbia, N.; Bulstra, L.F.; Thaler, R.; Hovius, S.E.R.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Shin, A.Y. In Vivo Survival of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Enhanced Decellularized Nerve Grafts for Segmental Peripheral Nerve Reconstruction. J. Hand Surg. 2019, 44, e1–e514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienstknecht, T.; Klein, S.; Vykoukal, J.; Gehmert, S.; Koller, M.; Gosau, M.; Prantl, L. Type I collagen nerve conduits for median nerve repairs in the forearm. J. Hand Surg. 2013, 38, 1119–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmeyer, J.A.; Sommer, B.; Siemers, F.; Mailänder, P. Nerve injuries of the upper extremity-expected outcome and clinical examination. Plast. Surg. Nurs. Off. 2009, 29, 88–93; quiz 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorogina, L.; Verbakh, T.; Malishevsky, V.; Byrke, I.; Chakhchakhov, Y.; Startseva, O.; Gabriyanchik, M. Reconstruction of chronic nerve injuries using artificial nerve conduits: A case series. Chin. J. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2025, 7, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, L.; Bellemere, P.; Loubersac, T.; Gaisne, E.; Poirier, P.; Chaise, F. Treatment by collagen conduit of painful post-traumatic neuromas of the sensitive digital nerve: A retrospective study of 10 cases. Chir. Main. 2010, 29, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childe, J.R.; Regal, S.; Schimoler, P.; Kharlamov, A.; Miller, M.C.; Tang, P. Fibrin Glue Increases the Tensile Strength of Conduit-Assisted Primary Digital Nerve Repair. Hand 2018, 13, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chow, N.; Miears, H.; Cox, C.; MacKay, B. Fibrin Glue and Its Alternatives in Peripheral Nerve Repair. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2021, 86, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, Y.M.; Judge, N.G.; Hu, Y.; Willits, R.K.; Li, N.; Becker, M.L. Review of Gaps in the Clinical Indications and Use of Neural Conduits and Artificial Grafts for Nerve Repair and Reconstruction. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 3974–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, M.; Lin, L.; Luo, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhang, J.; Qiu, T.; Liu, Z.; Yin, J.; Yu, M. Potentially commercializable nerve guidance conduits for peripheral nerve injury: Past, present, and future. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DR | CAR | |

|---|---|---|

| Nerves (N) | 705 | 436 |

| Mean gap length (mm) | NA | 10 |

| MRC sensory recovery (S3+ and S4) | 48.6% | 69.3% |

| Static 2PD | ||

| <6 mm: | 47.4% | 46.5% |

| 7–15 mm | 45.6% | 35.6% |

| >15 mm | 7.0% | 17.8% |

| SWMT | ||

| Full recovery | 34.2% | 32.8% |

| DLT | 37.7% | 32.8% |

| DPS | 19.2% | 23.4% |

| LPS | 4.4% | 10.9% |

| Anesthetic | 4.4% | 0% |

| MRC motor recovery (M4–M5) | 42.8% | 56.3% |

| Mean DASH score | 13.2 | 18.2 |

| Complications | ||

| Cold intolerance | 10.6% | 0.6% |

| Neuroma formation | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Altered sensation | 17.5% | 0.3% |

| Pain | 17.5% | 0.6% |

| Revision surgery | 0% | 9.2% |

| Fistula | 0% | 0.8% |

| Mean follow-up (months) | 26 | 23.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agosti, E.; Zeppieri, M.; Ius, T.; Antonietti, S.; Gelmini, L.; Denaro, L.; Bonetti, A.; Fontanella, M.M.; Ortolani, F.; Panciani, P.P. Comparative Outcomes of Direct Versus Connector-Assisted Peripheral Nerve Repair. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122954

Agosti E, Zeppieri M, Ius T, Antonietti S, Gelmini L, Denaro L, Bonetti A, Fontanella MM, Ortolani F, Panciani PP. Comparative Outcomes of Direct Versus Connector-Assisted Peripheral Nerve Repair. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122954

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgosti, Edoardo, Marco Zeppieri, Tamara Ius, Sara Antonietti, Lorenzo Gelmini, Luca Denaro, Antonella Bonetti, Marco Maria Fontanella, Fulvia Ortolani, and Pier Paolo Panciani. 2025. "Comparative Outcomes of Direct Versus Connector-Assisted Peripheral Nerve Repair" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122954

APA StyleAgosti, E., Zeppieri, M., Ius, T., Antonietti, S., Gelmini, L., Denaro, L., Bonetti, A., Fontanella, M. M., Ortolani, F., & Panciani, P. P. (2025). Comparative Outcomes of Direct Versus Connector-Assisted Peripheral Nerve Repair. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2954. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122954