Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Rheumatoid Immune Diseases: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. TRM Cell Biology in Rheumatoid Immune Diseases

2.1. Development and Maintenance Mechanisms of TRM Cells

2.1.1. Key Regulatory Signals

2.1.2. Metabolic Adaptation Mechanisms

2.2. Heterogeneity and Disease Specificity of TRM Cells

2.2.1. Tissue-Distribution Heterogeneity

2.2.2. Functional Heterogeneity

Pro-Inflammatory TRM Cells: Drivers of Tissue Damage

Regulatory TRM Cells: Guardians of Local Protection

2.3. Disease-Specific TRM Cells Revealed by Single-Cell Sequencing

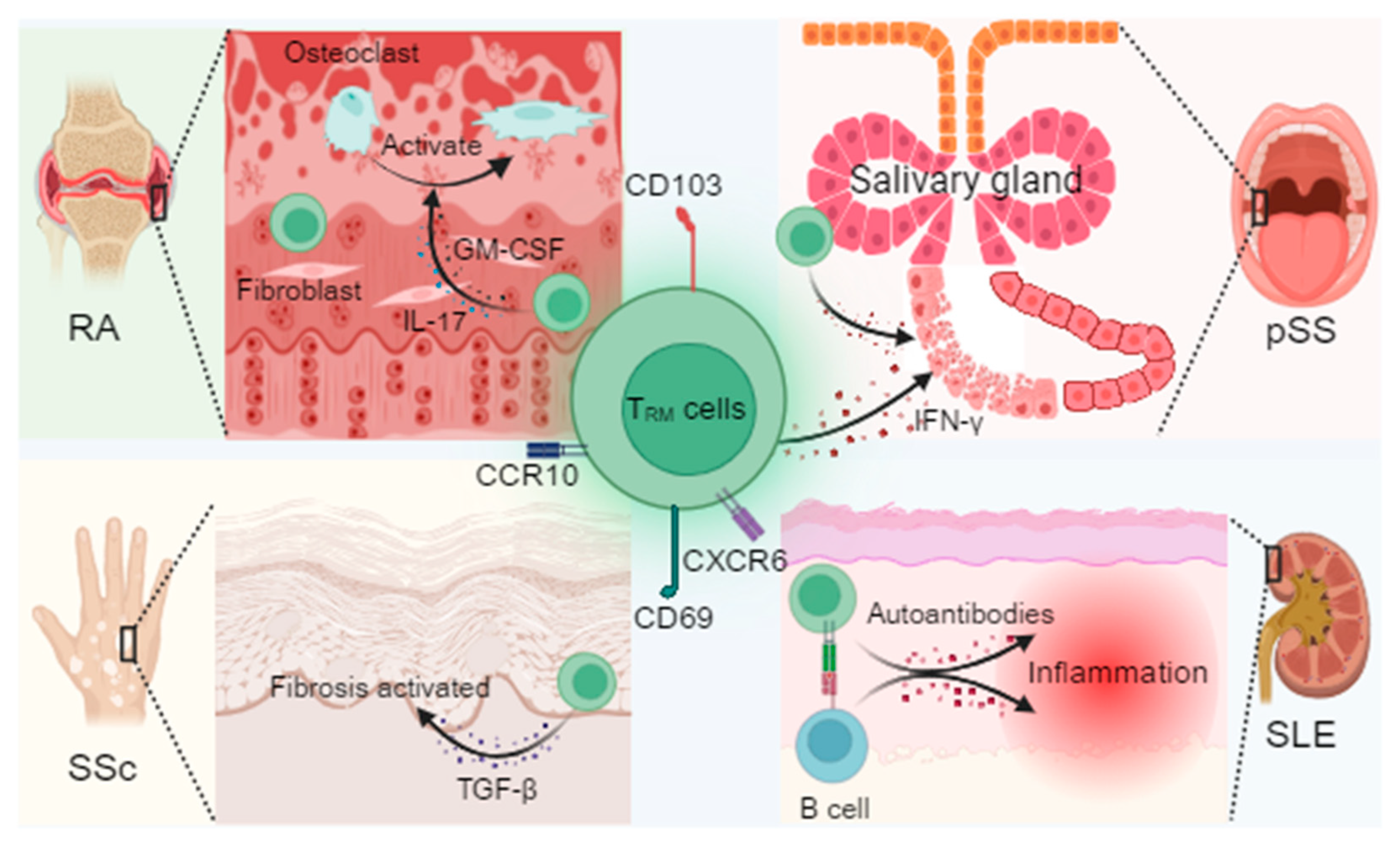

3. TRM Cell-Driven Pathogenic Mechanisms

3.1. TRM Cell-Mediated Pathogenic Mechanisms in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

3.1.1. Synovial TRM Cells–Fibroblast Crosstalk and Promotion of Osteoclastogenesis

3.1.2. Role of the IL-23/IL-17 Positive Feedback Loop in Maintaining Chronic Inflammation

3.1.3. Extra-Articular Manifestations

3.2. TRM Cell Pathogenesis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE)

3.2.1. Long-Term Retention of Skin TRM Cells and Production of Type I Interferon

3.2.2. The Formation of TRM Cells and B Cell Immune Synapses in the Kidney Promotes the Production of Autoantibodies

3.3. TRM Cell-Mediated Pathogenic Mechanisms in Systemic Sclerosis (SSc)

3.3.1. TRM Cell-Derived TGF-β as a Driver of Cutaneous and Vascular Fibrosis

3.3.2. Epigenetic Reprogramming Underlies Aberrant TRM Cell Activation

3.4. TRM Cell-Mediated Pathogenic Mechanisms in Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome (pSS)

4. Therapeutic Targeting of TRM Cells in Rheumatoid Immune Diseases

4.1. Drug Repurposing

4.1.1. JAK Inhibitors

4.1.2. Anti-IL-17/23 Antibodies

4.1.3. Low-Dose Radiotherapy (LDRT)

4.2. Emerging Targeted Strategies

4.2.1. Disrupting Residency Signals

4.2.2. Metabolic Interventions

4.3. Microenvironment-Remodeling Strategies

4.3.1. Smart Nanoparticle Delivery of siRNA

4.3.2. Synthetic-Biology Engineering of Fibroblasts

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

5.1. Challenges for Clinical Translation

5.1.1. Difficulties in Tissue-Specific Targeting

5.1.2. Potential Impacts of TRM Cell Depletion on Immune Memory

5.2. Key Technological Directions

5.2.1. Spatial Transcriptomics: Mapping TRM Cells–Stroma Interactions

5.2.2. Organoid Models: Modeling Long-Term TRM Cell Persistence and Optimizing Drug Discovery

5.2.3. AI-Guided Epigenetic Target Discovery for Precision Therapy

5.3. The Future of Individualized Therapy

5.3.1. TRM Cell Biomarker Assessment

5.3.2. Combination Therapies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TRM cells | Tissue-resident memory T cells |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| SSc | Systemic sclerosis |

| pSS | Primary Sjögren’s syndrome |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| CCL5 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 |

| TCR | T cell receptor |

| IL-15 | Interleukin-15 |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor |

| FAO | Fatty acid oxidation |

| CPT1a | Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase 1A |

| IL-7 | Interleukin-7 |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α |

| PD-1 | Programmed death receptor 1 |

| SSc-ILD | SSc-associated interstitial lung disease |

| RA-ILD | RA-associated interstitial lung disease |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| LT-α | Lymphotoxin-α |

| LDRT | Low-dose radiotherapy |

| S1P | Sphingosine-1-phosphate |

| FLS | Fibroblast-like synoviocytes |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| TPL | Triptolide |

| TLNPs | Targeted lipid nanoparticles |

| Treg | Regulatory T cells |

| Breg | Regulatory B cells |

References

- Firestein, G.S.; McInnes, I.B. Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity 2017, 46, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, T.; Kang, S. IL-6 Revisited: From Rheumatoid Arthritis to CAR T Cell Therapy and COVID-19. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 40, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harigai, M.; Honda, S. Selectivity of Janus Kinase Inhibitors in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Immune-Mediated Inflamma tory Diseases: Is Expectation the Root of All Headache? Drugs 2020, 80, 1183–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Xu, W.; Chang, F.; Wang, Y.; Ding, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Involved Strategies for Rheumatoid Arthritis Therapy. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2305116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schett, G.; Mackensen, A.; Mougiakakos, D. CAR T-cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Lancet 2023, 402, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tan, J.; Wang, N.; Li, H.; Cheng, W.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Sedgwick, A.C.; Chen, Z.; Chen, G.; et al. Specific macrophage RhoA targeting CRISPR-Cas9 for mitigating osteoclastogenesis-induced joint damage in inflammatory arthritis. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D.; McInnes, I.B. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2023–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crickx, E.; Weill, J.-C.; Reynaud, C.-A.; Mahévas, M. Anti-CD20-mediated B-cell depletion in autoimmune diseases: Successes, failures and future perspectives. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.N.; Mackay, L.K. Tissue-resident memory T cells: Local specialists in immune defence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.O.; Kupper, T.S. The emerging role of resident memory T cells in protective immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masopust, D.; Soerens, A.G. Tissue-Resident T Cells and Other Resident Leukocytes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 37, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, D.E.; Mohamed, A.; Huang, Y.H.; Turk, M.J. In the right place at the right time: Tissue-resident memory T cells in immunity to cancer. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2023, 83, 102338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.; Lu, G.; Mai, G.; Guo, Q.; Xu, G. Tissue-resident memory T cells in diseases and therapeutic strategies. MedComm 2025, 6, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsen, D.; van Gisbergen, K.P.J.M.; Hombrink, P.; van Lier, R.A.W. Tissue-resident memory T cells at the center of immunity to solid tumors. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shen, Z. Tissue-resident memory T cells and their biological characteristics in the recurrence of inflammatory skin disorders. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.V.; Ma, W.; Miron, M.; Granot, T.; Guyer, R.S.; Carpenter, D.J.; Senda, T.; Sun, X.; Ho, S.-H.; Lerner, H.; et al. Human Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Are Defined by Core Transcriptional and Functional Signatures in Lymphoid and Mucosal Sites. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2921–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zhou, R.; Chen, Z. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cell: Ontogenetic Cellular Mechanism and Clinical Translation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2023, 214, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, K.J.A.; Srenathan, U.; Ridley, M.; Durham, L.E.; Wu, S.-Y.; Ryan, S.E.; Hughes, C.D.; Chan, E.; Kirkham, B.W.; Taams, L.S. Polyfunctional, Proinflammatory, Tissue-Resident Memory Phenotype and Function of Synovial Interleukin-17A+CD8+ T Cells in Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallett, L.J.; Davies, J.; Colbeck, E.J.; Robertson, F.; Hansi, N.; Easom, N.J.W.; Burton, A.R.; Stegmann, K.A.; Schurich, A.; Swadling, L.; et al. IL-2high tissue-resident T cells in the human liver: Sentinels for hepatotropic infection. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 1567–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.H.; Levescot, A.; Nelson-Maney, N.; Blaustein, R.B.; Winden, K.D.; Morris, A.; Wactor, A.; Balu, S.; Grieshaber-Bouyer, R.; Wei, K.; et al. Arthritis flares mediated by tissue-resident memory T cells in the joint. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiao, C.; Li, C.; He, J. Tissue-resident immune cells: From defining characteristics to roles in diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, J.J.; Goldrath, A.W. Transcriptional programming of tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 51, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, L.K.; Minnich, M.; Kragten, N.A.M.; Liao, Y.; Nota, B.; Seillet, C.; Zaid, A.; Man, K.; Preston, S.; Freestone, D.; et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science 2016, 352, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varanasi, S.K.; Kumar, S.V.; Rouse, B.T. Determinants of Tissue-Specific Metabolic Adaptation of T Cells. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.; Chiu, Y.; Shaw, R.M.; Wang, J.; Yee, C. Hypoxia acts as an environmental cue for the human tissue-resident memory T cell differentiation program. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e138970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgnac, S.; Boutet, M.; Kfoury, M.; Naltet, C.; Mami-Chouaib, F. The Emerging Role of CD8+ Tissue Resident Memory T (TRM) Cells in Antitumor Immunity: A Unique Functional Contribution of the CD103 Integrin. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Bevan, M.J. Transforming growth factor-β signaling controls the formation and maintenance of gut-resident memory T cells by regulating migration and retention. Immunity 2013, 39, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Z.; Chu, T.H.; Sheridan, B.S. TGF-β: Many Paths to CD103+ CD8 T Cell Residency. Cells 2021, 10, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Deng, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Bi, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, J. Tissue-resident immune cells in cervical cancer: Emerging roles and therapeutic implications. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1541950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarjour, N.N.; Wanhainen, K.M.; Peng, C.; Gavil, N.V.; Maurice, N.J.; Borges da Silva, H.; Martinez, R.J.; Dalzell, T.S.; Huggins, M.A.; Masopust, D.; et al. Responsiveness to interleukin-15 therapy is shared between tissue-resident and circulating memory CD8+ T cell subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2209021119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Bhanumathy, K.K.; Wu, J.; Ye, Z.; Freywald, A.; Leary, S.C.; Li, R.; Xiang, J. IL-15 signaling promotes adoptive effector T-cell survival and memory formation in irradiation-induced lymphopenia. Cell Biosci. 2016, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Kim, Y.; Jung, Y.W. The Function of Memory CD8+ T Cells in Immunotherapy for Human Diseases. Immune Netw. 2023, 23, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Tang, T.-X.; Deng, H.; Yang, X.-P.; Tang, Z.-H. Interleukin-7 Biology and Its Effects on Immune Cells: Mediator of Generation, Differentiation, Survival, and Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 747324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Bergsbaken, T.; Edelblum, K.L. The multifunctional nature of CD103 (αEβ7 integrin) signaling in tissue-resident lym phocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 323, C1161–C1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topham, D.J.; Reilly, E.C. Tissue-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells: From Phenotype to Function. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, R.J. Regulation of T Cell Activation and Metabolism by Transforming Growth Factor-Beta. Biology 2023, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gracht, E.T.I.; Behr, F.M.; Arens, R. Functional Heterogeneity and Therapeutic Targeting of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Tian, T.; Park, C.O.; Lofftus, S.Y.; Mei, S.; Liu, X.; Luo, C.; O’Malley, J.T.; Gehad, A.; Teague, J.E.; et al. Survival of tissue-resident memory T cells requires exogenous lipid uptake and metabolism. Nature 2017, 543, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-J.; Glatman Zaretsky, A.; Andrade-Oliveira, V.; Collins, N.; Dzutsev, A.; Shaik, J.; Morais da Fonseca, D.; Harrison, O.J.; Tamoutounour, S.; Byrd, A.L.; et al. White Adipose Tissue Is a Reservoir for Memory T Cells and Promotes Protective Memory Responses to Infection. Immunity 2017, 47, 1154–1168.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liikanen, I.; Lauhan, C.; Quon, S.; Omilusik, K.; Phan, A.T.; Bartrolí, L.B.; Ferry, A.; Goulding, J.; Chen, J.; Scott-Browne, J.P.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor activity promotes antitumor effector function and tissue residency by CD8+ T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e143729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yfantis, A.; Mylonis, I.; Chachami, G.; Nikolaidis, M.; Amoutzias, G.D.; Paraskeva, E.; Simos, G. Transcriptional Response to Hypoxia: The Role of HIF-1-Associated Co-Regulators. Cells 2023, 12, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Ojo, O.A.; Ding, H.; Mullen, L.J.; Xing, C.; Hossain, M.I.; Yassin, A.; Shi, V.Y.; Lewis, Z.; Podgorska, E.; et al. HIF1α-regulated glycolysis promotes activation-induced cell death and IFN-γ induction in hypoxic T cells. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, L.; Peng, R. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 and Mitochondria: An Intimate Connection. Biomolecules 2022, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanumegowda, C.; Mohan, M.E. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α in Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Promising Therapeutic Target. Euro Pean J. Med. Health Sci. 2025, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Dudek, J.; Maack, C.; Hofmann, U. Pharmacological inhibition of GLUT1 as a new immunotherapeutic approach after myocardial infarction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 190, 114597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, M.; Park, S.L.; Mackay, L.K. Tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells: Front-line workers of the immune system. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, e2250060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.-G. The Interplay Between TGF-β Signaling and Cell Metabolism. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 846723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkgraaf, F.E.; Kok, L.; Schumacher, T.N.M. Formation of Tissue-Resident CD8+ T-Cell Memory. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2021, 13, a038117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjunpää, H.; Somermäki, R.; Saldo Rubio, G.; Fusciello, M.; Feola, S.; Faisal, I.; Nieminen, A.I.; Wang, L.; Llort Asens, M.; Zhao, H.; et al. Loss of β2-integrin function results in metabolic reprogramming of dendritic cells, leading to increased dendritic cell functionality and anti-tumor responses. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13, 2369373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splitt, R.L.; DeMali, K.A. Metabolic reprogramming in response to cell mechanics. Biol. Cell 2023, 115, e202200108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Ferreira, C.; Veldhoen, M. The fellowship of regulatory and tissue-resident memory cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christo, S.N.; Park, S.L.; Mueller, S.N.; Mackay, L.K. The Multifaceted Role of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 42, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.Z.M.; Wakim, L.M. Tissue resident memory T cells in the respiratory tract. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gisbergen, K.P.J.M.; Zens, K.D.; Münz, C. T-cell memory in tissues. Eur. J. Immunol. 2021, 51, 1310–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samat, A.A.K.; van der Geest, J.; Vastert, S.J.; van Loosdregt, J.; van Wijk, F. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Chronic In flammation-Local Cells with Systemic Effects? Cells 2021, 10, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, J.S.; Farsakoglu, Y.; Amezcua Vesely, M.C.; Sefik, E.; Kelly, J.B.; Harman, C.C.D.; Jackson, R.; Shyer, J.A.; Jiang, X.; Cauley, L.S.; et al. Tissue-resident memory T cell reactivation by diverse antigen-presenting cells imparts distinct functional responses. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20192291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, C.-H.; Lee, S.; Kwak, M.; Kim, B.-S.; Chung, Y. CD8 T-cell subsets: Heterogeneity, functions, and therapeutic potential. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 2287–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, S. Corrigendum: Heterogeneity and plasticity of tissue-resident memory T cells in skin diseases and homeostasis: A review. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1460250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeg, M.; Goldrath, A.W. Insights into phenotypic and functional CD8+ TRM heterogeneity. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 316, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.E.; Foreman, T.W.; Fukutani, E.R.; Kauffman, K.D.; Sakai, S.; Fleegle, J.D.; Gomez, F.; Gould, S.T.; Le Nouën, C.; Liu, X.; et al. IL-10 suppresses T cell expansion while promoting tissue-resident memory cell formation during SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenyuwadee, S.; Sanchez-Trincado Lopez, J.L.; Shah, R.; Rosato, P.C.; Boussiotis, V.A. The evolving role of tissue-resident memory T cells in infections and cancer. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musial, S.C.; Kleist, S.A.; Degefu, H.N.; Ford, M.A.; Chen, T.; Isaacs, J.F.; Boussiotis, V.A.; Skorput, A.G.J.; Rosato, P.C. Alarm Functions of PD-1+ Brain-Resident Memory T Cells. J. Immunol. 2024, 213, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodger, B.; Stagg, A.J.; Lindsay, J.O. The role of circulating T cells with a tissue resident phenotype (ex-TRM) in health and disease. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1415914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzolla, A.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; Sant, S.; Jaffar, J.; Loudovaris, T.; Mannering, S.I.; Thomas, P.G.; Westall, G.P.; Kedzierska, K.; Wakim, L.M. Influenza-specific lung-resident memory T cells are proliferative and polyfunctional and maintain diverse TCR profiles. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesini Tovar, G.; Gallen, C.; Bergsbaken, T. CD8+ Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells: Versatile Guardians of the Tissue. J. Immunol. 2024, 212, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, N. The emerging role of effector functions exerted by tissue-resident memory T cells. Oxf. Open Immunol. 2024, 5, iqae006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, E.C.; Sportiello, M.; Emo, K.L.; Amitrano, A.M.; Jha, R.; Kumar, A.B.R.; Laniewski, N.G.; Yang, H.; Kim, M.; Topham, D.J. CD49a Identifies Polyfunctional Memory CD8 T Cell Subsets that Persist in the Lungs After Influenza Infection. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 728669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povoleri, G.A.M.; Durham, L.E.; Gray, E.H.; Lalnunhlimi, S.; Kannambath, S.; Pitcher, M.J.; Dhami, P.; Leeuw, T.; Ryan, S.E.; Steel, K.J.A.; et al. Psoriatic and rheumatoid arthritis joints differ in the composition of CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cell subsets. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sul, C.; Nozik, E.; Malainou, C. A Tale of Two Cytokines: IL-10 Blocks IFN-γ in Influenza A Virus-Staphylococcus aureus Coinfection. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2024, 71, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Goplen, N.P.; Li, C.; Cheon, I.S.; Dai, Q.; Huang, S.; Shan, J.; Ma, C.; Ye, Z.; et al. PD-1hi CD8+ resident memory T cells balance immunity and fibrotic sequelae. Sci. Immunol. 2019, 4, eaaw1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, S.P.; Carpenter, D.J.; Chait, M.; Dogra, P.; Gartrell-Corrado, R.D.; Chen, A.X.; Campbell, S.; Liu, W.; Saraf, P.; Snyder, M.E.; et al. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells Mediate Immune Homeostasis in the Human Pancreas through the PD-1/PD-L1 Pathway. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 3916–3932.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overacre-Delgoffe, A.E.; Hand, T.W. Regulation of tissue-resident memory T cells by the Microbiota. Mucosal Immunol. 2022, 15, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyriou, A.; Wadsworth, M.H.; Lendvai, A.; Christensen, S.M.; Hensvold, A.H.; Gerstner, C.; van Vollenhoven, A.; Kravarik, K.; Winkler, A.; Malmström, V.; et al. Single cell sequencing identifies clonally expanded synovial CD4+ TPH cells expressing GPR56 in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Slowikowski, K.; Fonseka, C.Y.; Rao, D.A.; Kelly, S.; Goodman, S.M.; Tabechian, D.; Hughes, L.B.; Salomon-Escoto, K.; et al. Defining inflammatory cell states in rheumatoid arthritis joint synovial tissues by integrating single-cell transcriptomics and mass cytometry. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyriou, A. Immunoprofiling the Inflamed Tissue in Rheumatic Diseases Using Single-Cell Technologies. Ph.D. Thesis, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Strobl, J.; Haniffa, M. Functional heterogeneity of human skin-resident memory T cells in health and disease. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 316, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, G.S.; Billi, A.C.; Xing, X.; Ma, F.; Maz, M.P.; Tsoi, L.C.; Wasikowski, R.; Hodgin, J.B.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Kahlenberg, J.M.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals distinct effector profiles of infiltrating T cells in lupus skin and kidney. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e156341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Hoogen, F.; Khanna, D.; Fransen, J.; Johnson, S.R.; Baron, M.; Tyndall, A.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Naden, R.P.; Medsger, T.A.; Carreira, P.E.; et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: An American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaydosik, A.M.; Tabib, T.; Domsic, R.; Khanna, D.; Lafyatis, R.; Fuschiotti, P. Single-cell transcriptome analysis identifies skin-specific T-cell responses in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimagami, H.; Nishimura, K.; Matsushita, H.; Metsugi, S.; Kato, Y.; Kawasaki, T.; Tsujimoto, K.; Edahiro, R.; Itotagawa, E.; Naito, M.; et al. Single-cell analysis reveals immune cell abnormalities underlying the clinical heterogeneity of patients with systemic sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, C.M.; Valenzi, E.; Tabib, T.; Nazari, B.; Sembrat, J.; Rojas, M.; Fuschiotti, P.; Lafyatis, R. Increased CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells, regulatory T cells and activated natural killer cells in systemic sclerosis lungs. Rheumatology 2024, 63, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhu, H.-X.; You, X.; Ma, J.-F.; Li, X.; Luo, P.-Y.; Li, Y.; Lian, Z.-X.; Gao, C.-Y. Single-cell profiling reveals pathogenic role and differentiation trajectory of granzyme K+CD8+ T cells in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e167490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, D.; Lin, X.; Pontarini, E.; Wehr, P.; Guggino, G.; Tang, Y.; Deng, C.; Gandolfo, S.; Xiao, F.; Rui, K.; et al. CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells are expanded in primary Sjögren’s disease and can be therapeutically targeted by CD103 blockade. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liao, W.; Li, Q.; Long, H.; Yin, H.; Zhao, M.; Chan, V.; Lau, C.S.; Lu, Q. Pathogenic role of tissue-resident memory T cells in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, A.; Zhao, W.; Wu, R.; Su, R.; Jin, R.; Luo, J.; Gao, C.; Li, X.; Wang, C. Tissue-resident memory T cells: The key frontier in local synovitis memory of rheumatoid arthritis. J. Autoimmun. 2022, 133, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.E.; Harris, J.E.; Richmond, J.M. Resident Memory T Cells in Autoimmune Skin Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 652191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, S.; Tolusso, B.; Ferraccioli, G.; Gremese, E.; Kurowska-Stolarska, M.; McInnes, I.B. Driving chronicity in rheumatoid arthritis: Perpetuating role of myeloid cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 193, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, I.B.; Schett, G. Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2017, 389, 2328–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestein, G.S. The immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 1991, 3, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, N.; Kuroda, T.; Kobayashi, D. Cytokine Networks in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, A.; McInnes, I.B. IL-23 orchestrating immune cell activation in arthritis. Rheumatology 2021, 60, iv4–iv15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, K.-W.; Park, M.-K.; Moon, Y.; Kim, W.-U.; Kim, H.-Y. IL-17 induces production of IL-6 and IL-8 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts via NF-kappaB- and PI3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathways. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2004, 6, R120–R128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Ito, Y.; Matsuura, M.; Ito, H.; Tanaka, M.; Watanabe, H.; Kondoh, G.; Tanaka, A.; Yasuda, K.; et al. Autoimmune Th17 Cells Induced Synovial Stromal and Innate Lymphoid Cell Secretion of the Cytokine GM-CSF to Initiate and Augment Autoimmune Arthritis. Immunity 2018, 48, 1220–1232.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Anzaghe, M.; Schülke, S. Update on the Pathomechanism, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options for Rheumatoid Ar thritis. Cells 2020, 9, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadura, S.; Raghu, G. Rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease: Manifestations and current concepts in pathogenesis and management. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 210011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredi, A.; Cassone, G.; Luppi, F.; Atienza-Mateo, B.; Cavazza, A.; Sverzellati, N.; González-Gay, M.A.; Salvarani, C.; Sebastiani, M. Rheumatoid arthritis related interstitial lung disease. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 17, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.-J.; Song, S.; Roh, J.Y.; Jung, Y.; Kim, H.J. Expression pattern of tissue-resident memory T cells in cutaneous lupus ery thematosus. Lupus 2021, 30, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, D.; Yao, X.; Zhao, M.; Kumari, S.; Lu, J.; Yu, D.; Lu, Q. Dysregulation in keratinocytes drives systemic lupus erythematosus onset. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, F.B.; Figgett, W.A.; Hibbs, M.L. Hallmark of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Role of B Cell Hyperactivity. In Pathogenesis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Insights from Translational Research; Hoi, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bocharnikov, A.V.; Keegan, J.; Wacleche, V.S.; Cao, Y.; Fonseka, C.Y.; Wang, G.; Muise, E.S.; Zhang, K.X.; Arazi, A.; Keras, G.; et al. PD-1hiCXCR5– T peripheral helper cells promote B cell responses in lupus via MAF and IL-21. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e130062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanujam, M.; Steffgen, J.; Visvanathan, S.; Mohan, C.; Fine, J.S.; Putterman, C. Phoenix from the flames: Rediscovering the role of the CD40-CD40L pathway in systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altorok, N.; Kahaleh, B. Epigenetics and systemic sclerosis. Semin. Immunopathol. 2015, 37, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangogiannis, N. Transforming growth factor-β in tissue fibrosis. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Tang, R.; Ding, K. Epigenetic Modifications in the Pathogenesis of Systemic Sclerosis. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 3155–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ortiz-Fernández, L.; Andrés-León, E.; Ciudad, L.; Javierre, B.M.; López-Isac, E.; Guillén-Del-Castillo, A.; Simeón-Aznar, C.P.; Ballestar, E.; Martin, J. Epigenomics and transcriptomics of systemic sclerosis CD4+ T cells reveal long-range dysregulation of key inflammatory pathways mediated by disease-associated susceptibility loci. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, C.; Pötter, S.; Zhang, Y.; Bergmann, C.; Zhou, X.; Luber, M.; Wohlfahrt, T.; Karouzakis, E.; Ramming, A.; Gelse, K.; et al. TGF-β-induced epigenetic deregulation of SOCS3 facilitates STAT3 signaling to promote fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2347–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, E.R.; Andréasson, K.; Smith, V. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2023, 401, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, C.P.; Khanna, D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017, 390, 1685–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambudkar, I. Calcium signaling defects underlying salivary gland dysfunction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Molec Ular Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Makarenkova, H.P. Innate Immunity and Biological Therapies for the Treatment of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Inter Natl. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Suresh, L.; Wu, J.; Xuan, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Pankewycz, O.; Ambrus, J.L. A role for lymphotoxin in primary Sjogren’s disease. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 6355–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Chaudhari, K.S.; Kurien, B.T.; Grundahl, K.; Radfar, L.; Lewis, D.M.; Lessard, C.J.; Li, H.; Rasmussen, A.; Sivils, K.L.; et al. Sjögren Syndrome without Focal Lymphocytic Infiltration of the Salivary Glands. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yura, Y.; Hamada, M. Outline of Salivary Gland Pathogenesis of Sjögren’s Syndrome and Current Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt, A. Resident Memory T Cells in Psoriasis: Key to a Cure? J. Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis 2022, 7, 157–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Liu, F. Targeting the IL-15/CD122 signaling pathway: Reversing TRM cell-mediated immune memory in vitiligo. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1639732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattsson, J.; Israelsson, E.; Björhall, K.; Yrlid, L.F.; Thörn, K.; Thorén, A.; Toledo, E.A.; Jinton, L.; Öberg, L.; Wingren, C.; et al. Selective Janus kinase 1 inhibition resolves inflammation and restores hair growth offering a viable treatment option for alopecia areata. Ski. Health Dis. 2023, 3, e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yari, S.; Kikuta, J.; Shigyo, H.; Miyamoto, Y.; Okuzaki, D.; Furusawa, Y.; Minoshima, M.; Kikuchi, K.; Ishii, M. JAK inhibition ameliorates bone destruction by simultaneously targeting mature osteoclasts and their precursors. Inflamm. Regen. 2023, 43, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Li, S.; Ying, S.; Tang, S.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiao, J.; Fang, H. The IL-23/IL-17 Pathway in Inflammatory Skin Diseases: From Bench to Bedside. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 594735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Lin, L.; Du, J. Characteristics and sources of tissue-resident memory T cells in psoriasis relapse. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2023, 4, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-W.; Tsai, T.-F. A drug safety evaluation of risankizumab for psoriasis. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2020, 19, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, M.S.; Aktaş, H. The effect of IL-17 and IL-23 ınhibitors on hematological ınflammatory parameters in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 194, 1329–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.B.; Hernandez, R.; Carlson, P.; Grudzinski, J.; Bates, A.M.; Jagodinsky, J.C.; Erbe, A.; Marsh, I.R.; Arthur, I.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; et al. Low-dose targeted radionuclide therapy renders immunologically cold tumors responsive to immune checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-G.; Choi, H.S.; Choe, Y.-H.; Jeon, H.M.; Heo, J.Y.; Cheon, Y.-H.; Kang, K.M.; Lee, S.-I.; Jeong, B.K.; Kim, M. Low-Dose Radiotherapy Attenuates Experimental Autoimmune Arthritis by Inducing Apoptosis of Lymphocytes and Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes. Immune Netw. 2024, 24, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Játiva, S.; Torrico, S.; Calle, P.; Poch, E.; Muñoz, A.; García, M.; Larque, A.B.; Salido, M.T.T.; Hotter, G. The phagocytosis dys function in lupus nephritis is related to monocyte/macrophage CPT1a. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 266, 106841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, H.-J.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, E.-K.; Park, M.-J.; Kim, K.-W.; Park, S.-H.; Cho, M.-L. Metformin attenuates experimental autoimmune arthritis through reciprocal regulation of Th17/Treg balance and osteoclastogenesis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 973986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez Moret, Y.A.; Lo, K.B.; Tan, I.J. Metformin in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Investigating Cardiovascular Impact and Nephroprotective Effects in Lupus Nephritis. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2024, 6, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Yang, L.; Jiang, J.; Cao, J.; Sun, M.; Yin, L.; Zhong, Z.; Meng, F. Pre-silencing of TNF-α by targeted siRNA delivery mitigates glucocorticoid resistance of dexamethasone in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Control. Release 2025, 386, 114122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Ma, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Tang, Q.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, J. Microenvironment-driven transform able self-assembly nanoplatform enables spatiotemporal remodeling for rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadu5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Fibroblast activation and heterogeneity in fibrotic disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2025, 21, 613–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.; Jiao, Y.; Deng, T.; Gu, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, P.; Xu, N.; Xiao, C. Synovium-On-A-Chip: Simulating the Microenvironment of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovium via Multicell Interactions to Target Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes. Adv. Sci. 2025, e11945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.M.; Kim, W.-U. Targeted Immunotherapy for Autoimmune Disease. Immune Netw. 2022, 22, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zheng, Y.; Ran, X.; Du, H.; Feng, H.; Yang, L.; Wen, Y.; Lin, C.; Wang, S.; Huang, M.; et al. Integrin αEβ7+ T cells direct intestinal stem cell fate decisions via adhesion signaling. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 1291–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leask, A.; Fadl, A.; Naik, A. A modest proposal: Targeting αv integrin-mediated activation of latent TGFbeta as a novel thera peutic approach to treat scleroderma fibrosis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2024, 33, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Y.; He, Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, S.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.Y.; Qiu, H.-B.; Wang, W.; et al. Fatty Acid Oxidation Controls CD8+ Tissue-Resident Memory T-cell Survival in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Shah, R.B.; Singhal, S.; Dutta, S.B.; Bansal, S.; Sinha, S.; Haque, M. Metformin: A Review of Potential Mechanism and Therapeutic Utility Beyond Diabetes. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2023, 17, 1907–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Ye, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, F. Engineering the next generation of theranostic biomaterials with synthetic biology. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 32, 514–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.H.; Fuhlbrigge, R.C.; Nigrovic, P.A. Joint-specific memory, resident memory T cells and the rolling window of op portunity in arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2024, 20, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Daya, K.I.; Tieu, R.; Zhao, D.; Rammal, R.; Sacirbegovic, F.; Williams, A.L.; Shlomchik, W.D.; Oberbarnscheidt, M.H.; Lakkis, F.G. Resident memory T cells form during persistent antigen exposure leading to allograft rejection. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabc8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, A.; Liu, N.; Tan, Z.; Shi, Y.; Ma, T.; Luo, S.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, F.; et al. Integrative spatial multiomics analysis reveals regulatory mechanisms of VCAM1+ proximal tubule cells in lupus nephritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Gu, M.; Li, X.; Hu, X.; Chen, C.; Kang, Y.; Pan, B.; Chen, W.; Xian, G.; Wu, X.; et al. ITGA5+ synovial fibroblasts orchestrate proinflammatory niche formation by remodelling the local immune microenvironment in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2025, 84, 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recaldin, T.; Steinacher, L.; Gjeta, B.; Harter, M.F.; Adam, L.; Kromer, K.; Mendes, M.P.; Bellavista, M.; Nikolaev, M.; Lazzaroni, G.; et al. Human organoids with an autologous tissue-resident immune compartment. Nature 2024, 633, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, J.; Zhang, Q.; He, J.; Wang, Q. Constructing a 3D co-culture in vitro synovial tissue model for rheumatoid arthritis research. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.; Hahn, M.; Wauford, B.; Blaustein, R.; Wei, K.; Nigrovic, P. Generation of Human Resident Memory T Cells in 3D Synovial Organoid Model. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75 (Suppl. S4), 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Xu, L.; Chang, C.; Zhang, R.; Jin, Y.; He, D. Epigenetic Regulation Mediated by Methylation in the Pathogenesis and Precision Medicine of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballestar, E.; Sawalha, A.H.; Lu, Q. Clinical value of DNA methylation markers in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M. Tissue-resident memory T cells: Decoding intra-organ diversity with a gut perspective. Inflamm. Re Gener. 2024, 44, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.-F.; Zhao, N.; Hu, C.-H. Harnessing mesenchymal stem/stromal cells-based therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: Mecha nisms, clinical applications, and microenvironmental interactions. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, T.L.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Matsuda, D.; Riener, R.; Wang, A.; Li, J.J.; Soldevila, F.; Chu, D.S.H.; Nguyen, D.P.; et al. In vivo CAR T cell generation to treat cancer and autoimmune disease. Science 2025, 388, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Liu, P.; Liu, H. Re-establishing immune tolerance in multiple sclerosis: Focusing on novel mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell regulation of Th17/Treg balance. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Deng, X.; Yang, Y.; Xie, X.; Li, B.; Peng, X. Immuno-engineered macrophage membrane-coated nanodrug to restore immune balance for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Acta Biomater. 2025, 197, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Su, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Yan, C.; Liu, M.; Ji, H.; Lei, J.; Zheng, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Control of Proteasomal Psmb5 Drives the Differentiation of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2024, 76, 1743–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | TRM Cell Markers | Functional Subtypes | Pathogenic Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | CXCR6+ | IFN-γ+/TNF-α+ | GM-CSF secretion and IL-23/IL-17 axis activation enhance osteoclast activity | [73] |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | CCR10+ | IFN-γ+/IL-10+ | Continuous secretion of type I interferon activates B cells to promote autoantibody production | [76,77] |

| Systemic sclerosis (SSc) | Lung tissue: The memory phenotype is differentiated by CD45RO ↑ and the resting phenotype CD45RA ↑; (↑ indicates upregulation) | Lung tissue: CD8+ TRM cells are the main focus; | Lung tissue: TRM/Treg-driven TCR signaling, T cell exhaustion, and epithelial interaction associate with fibrosis. Skin: TRM cells-induced Th1/Th2 cytokine imbalance indicates chronic antigenic disruption of homeostasis. | [79,81] |

| Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) | Skin: CD69, ITGAE, CCR7, SELL | Skin: CD4+/CD8+ TRM cells and proliferative TRM cell clusters | Disruption of the structure of the gland, leading to loss of secretory function | [82,83] |

| Type | Medications/Methods | Mechanism | Applicable Diseases | Phase | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Repurposing | JAK inhibitors (Tofacitinib) | Block IL-15/JAK-STAT signaling → reduce TRM cell survival and cytokine production | RA, SLE | Clinical application | [115,116,117] |

| Anti-IL-17/23 antibodies (Secukinumab, Risankizumab) | Interrupt IL-23/IL-17 feedback loop → suppress TRM cell-driven inflammation | RA, pSS | Clinical application | [120,121] | |

| Residency-Targeting Approaches | S1PR1 agonist (Fingolimod) | Promote TRM cell relocation and reduce local retention | IBD | Clinical research | [55] |

| Metabolic regulation | Integrin αEβ7 inhibitors (Etrolizumab) | Inhibition of TRM cell fatty acid oxidation reduces survival | SLE | Preclinical research | [124] |

| CPT1a inhibitors | Regulates TRM cell metabolism through AMPK, limit RM cells fatty-acid oxidation | RA, SLE | Clinical research | [125,126] | |

| Microenvironment reshaping | Metformin | Targeted silencing of TRM cell pro-inflammatory factors | RA | Animal Experiments | [127,128] |

| Nanoparticles deliver siRNA | Induce anti-TRM cell factor secretion | RA | Preclinical research | [129,130] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, F.; Yang, Y.; Lu, G.; Xie, D. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Rheumatoid Immune Diseases: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122945

Tian Y, Zhang J, Wu L, Zhang C, Zheng F, Yang Y, Lu G, Xie D. Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Rheumatoid Immune Diseases: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122945

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Yu, Jie Zhang, Lianying Wu, Chi Zhang, Fan Zheng, Yang Yang, Guanting Lu, and Daoyuan Xie. 2025. "Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Rheumatoid Immune Diseases: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122945

APA StyleTian, Y., Zhang, J., Wu, L., Zhang, C., Zheng, F., Yang, Y., Lu, G., & Xie, D. (2025). Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells in Rheumatoid Immune Diseases: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2945. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122945