Animal Assisted Activities (AAAs) with Dogs in a Dialysis Center in Southern Italy: Evaluation of Serotonin and Oxytocin Values in Involved Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Patients

2.2. Methodology

2.3. AAA Team

2.4. Choice of the Dog

2.5. Behavioral and Infectious Safety of the Dog

2.6. Animal-Assisted Activities (AAAs)

2.7. Blood Sampling and Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

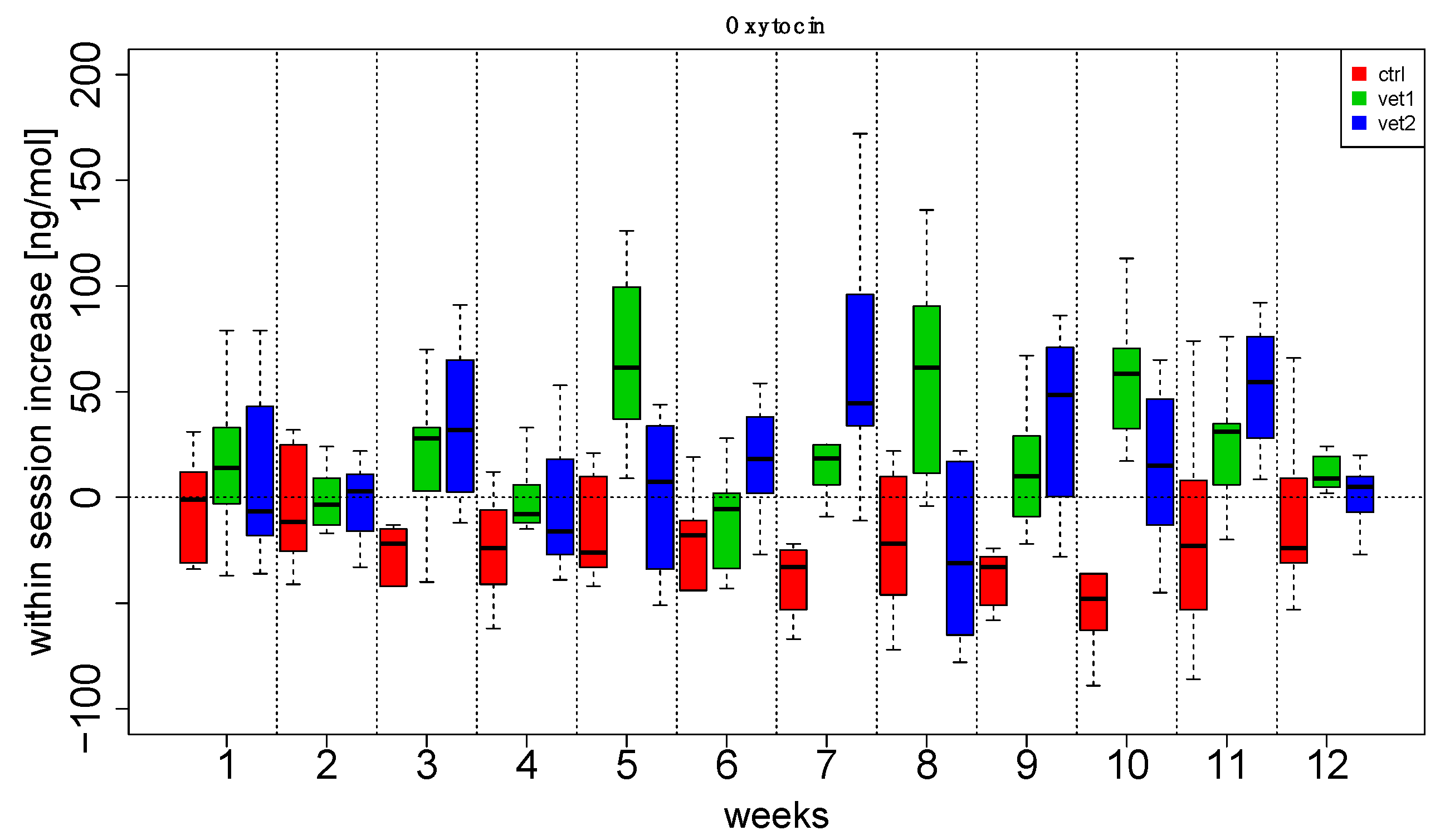

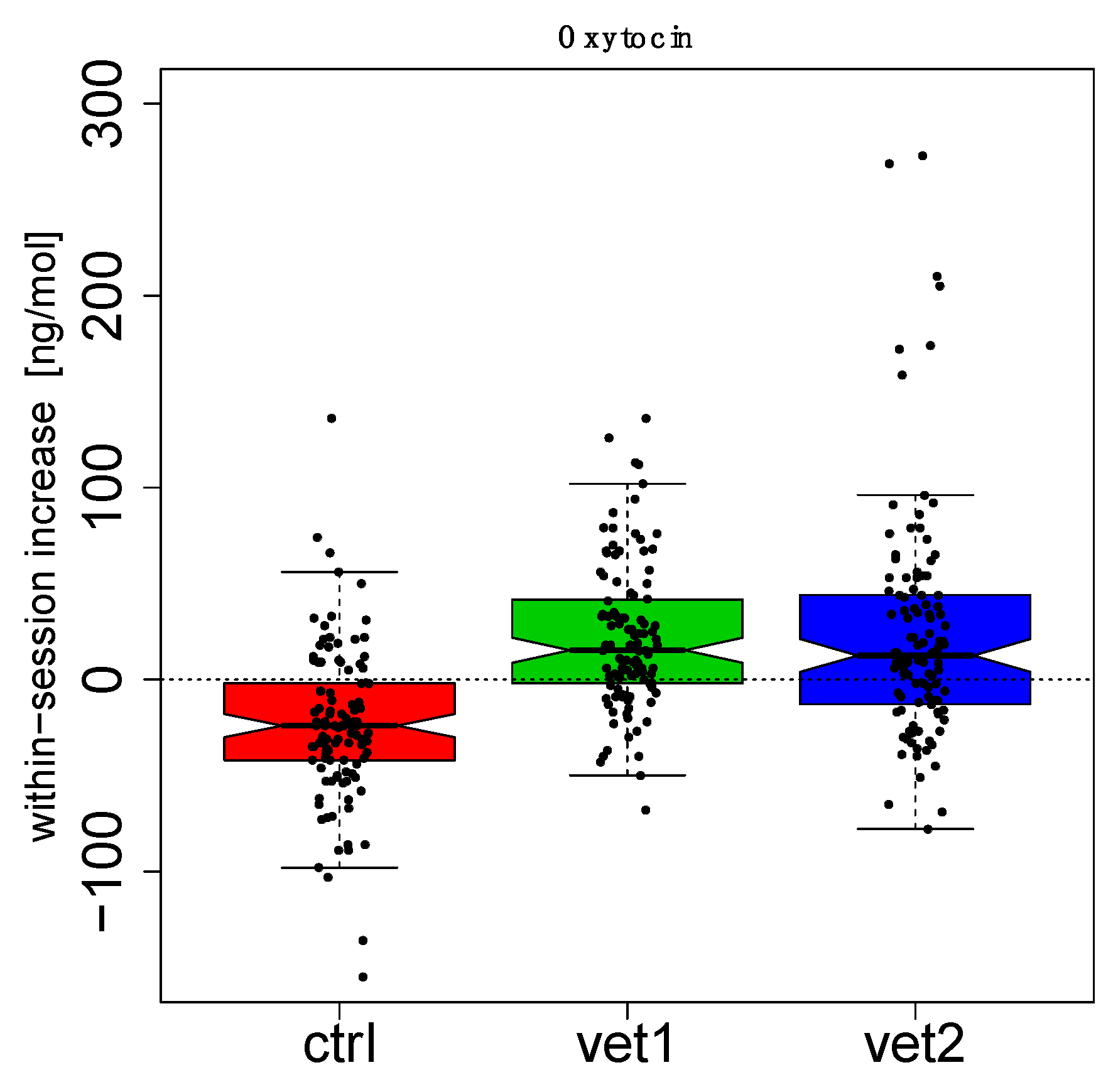

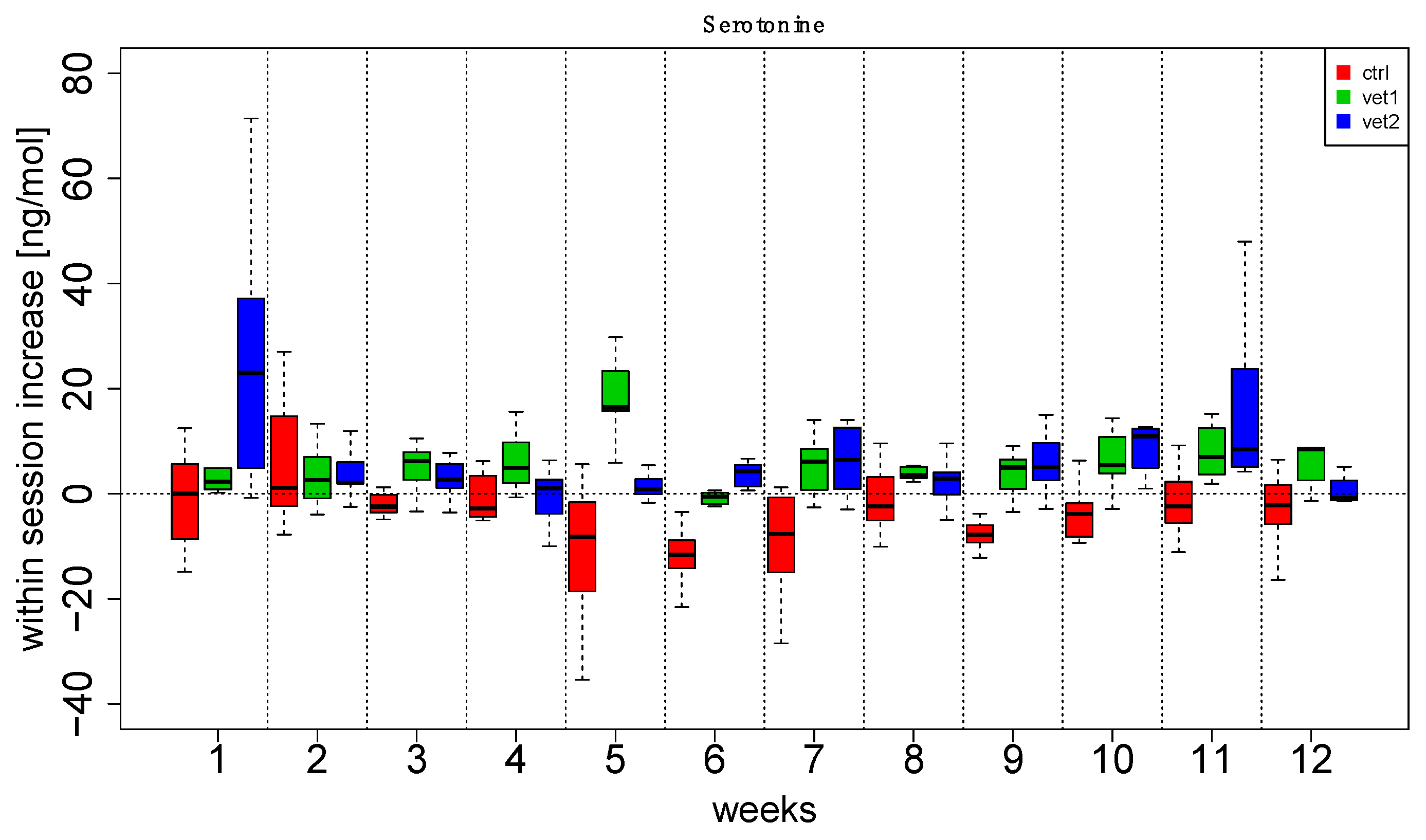

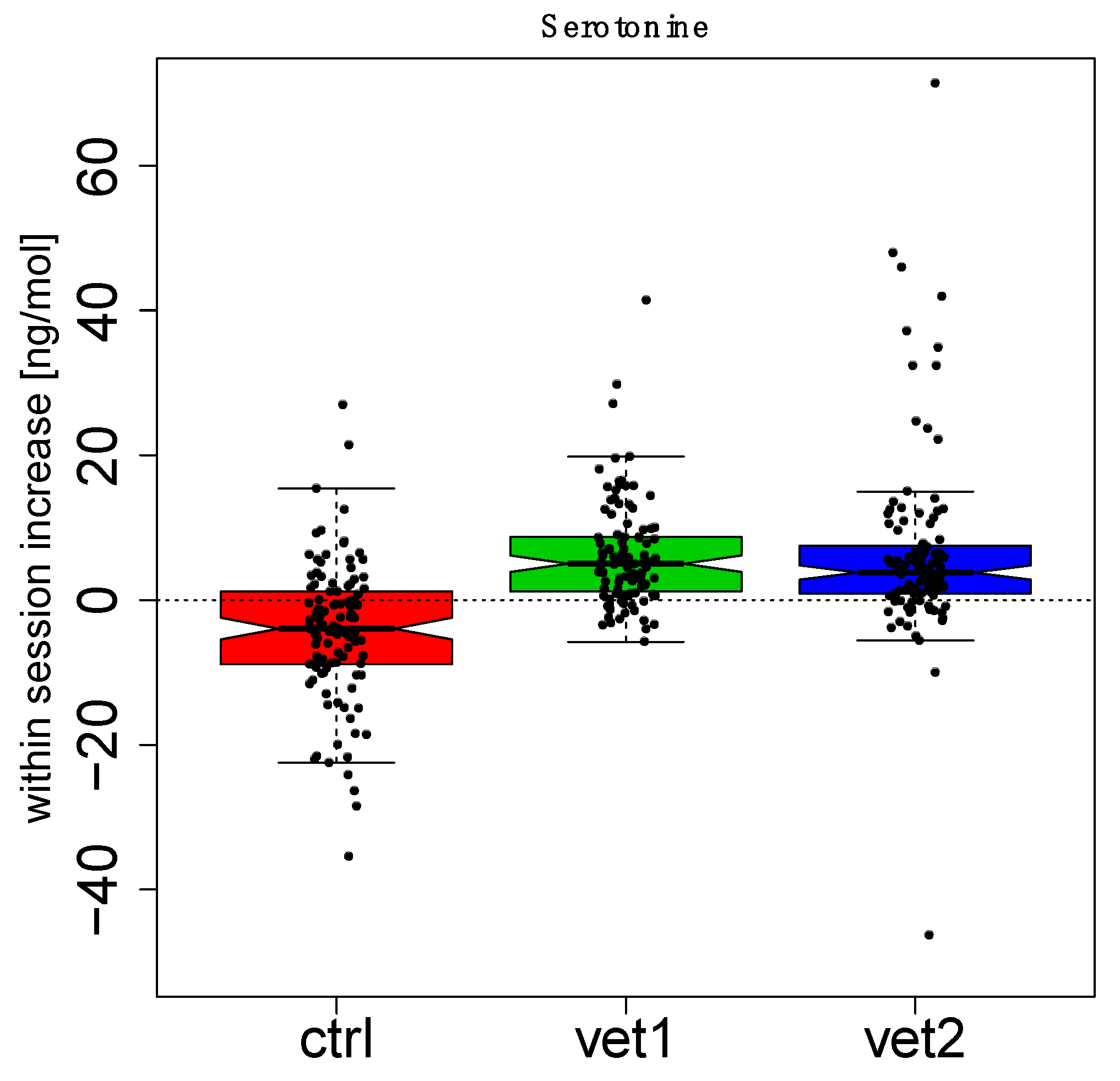

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAA | Animal Assisted Activities |

| AAIs | Animal Assisted Interventions |

| OXT | Oxytocin |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CTRL | Control |

References

- Overgaauw, P.A.M.; Vinke, C.M.; Hagen, M.; Lipman, L.J.A. A One health perspective on the human-companion animal relationship with emphasis on zoonotic aspects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAHAIO. IAHAIO White Paper 2014, U.f. The IAHAIO Definitions for Animal Assisted Intervention and Guidelines for Wellness of Animals Involved in AAI. 2018. Available online: http://iahaio.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/iahaio_wp_updated-2018-final.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Todisco, M.; Amato, A.; Borrelli, L.; Scandurra, C.; Fioretti, A. The human-animal relationship as the focus of Animal-Assisted Interventions: A One Health Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, E.; Krause-Parello, C.A. Companion animals and human health: Benefits, challenges, and the road ahead for human-animal interaction. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2018, 37, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchas, D.; Melaragni, M.; Abrahim, H.; Barchas, E. The best medicine: Personal pets and therapy animals in the hospital setting. Crit. Care Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 32, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinic, K.; Kowalski, M.O.; Holtzman, K.; Mobus, K. The effect of a pet therapy and comparison intervention on anxiety in hospitalized children. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 46, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbrizzi, C.; Sapuppo, W. Effects of Pet Therapy in elderly patients with neurocognitive disorders: A brief Review. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra 2021, 11, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santaniello, A.; Garzillo, S.; Amato, A.; Sansone, M.; Di Palma, A.; Di Maggio, A.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. Animal-Assisted Therapy as a non-pharmacological approach in alzheimer’s disease: A retrospective study. Animals 2020, 10, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceparano, G.T.G. Differences in emotional perceptions between oncology patients starting intravenous systemic treatment and nephropathic patients with an ongoing hemodialytic treatment. Top.-Temi Psicol. Dell’ordine Degli Psicol. Della Campania 2023, 2, 14–43. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.W.; Wee, P.H.; Low, L.L.; Koong, Y.L.A.; Htay, H.; Fan, Q.; Foo, W.Y.M.; Seng, J.J.B. Prevalence and risk factors for elevated anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2021, 69, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopple, J.D.; Shapiro, B.B.; Feroze, U.; Kim, J.C.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Martin, D.J. Hemodialysis treatment engenders anxiety and emotional distress. Clin. Nephrol. 2017, 88, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masia-Plana, A.; Juvinya-Canal, D.; Suner-Soler, R.; Sitjar-Suner, M.; Casals-Alonso, C.; Mantas-Jimenez, S. Pain, anxiety, and depression in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis treatment: A multicentre cohort study. Pain. Manag. Nurs. 2022, 23, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, C.M.; Edwards, D.; Ahdoot, R.S.; Burton, J.O.; Conway, P.T.; Fishbane, S.; Gallego, D.; Gallieni, M.; Gedney, N.; Hayashida, G.; et al. Living well with kidney disease and effective symptom management: Consensus conference proceedings. Kidney Int. Rep. 2022, 7, 1951–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, H.H.; Guo, H.R.; Livneh, H.; Lu, M.C.; Yen, M.L.; Tsai, T.Y. Increased risk of progression to dialysis or death in CKD patients with depressive symptoms: A prospective 3-year follow-up cohort study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 79, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVries, A.C.; Glasper, E.R.; Detillion, C.E. Social modulation of stress responses. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 79, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handlin, L.N.A.; Ejdebäck, M.; Hydbring-Sandberg, E.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K. Associations between the psychological characteristics of the human–dog relationship and oxytocin and cortisol levels. Anthrozoös 2012, 25, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.C.; Kennedy, C.C.; DeVoe, D.C.; Hickey, M.; Nelson, T.; Kogan, L. An examination of changes in oxytocin levels in men and women before and after interaction with a bonded dog. Anthrozoös 2009, 22, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, M.; Kikusui, T.; Onaka, T.; Ohta, M. Dog’s gaze at its owner increases owner’s urinary oxytocin during social interaction. Horm. Behav. 2009, 55, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehn, T.; Handlin, L.; Uvnas-Moberg, K.; Keeling, L.J. Dogs’ endocrine and behavioural responses at reunion are affected by how the human initiates contact. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 124, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöberl, I.B.A.; Solomon, J.; Wedl, M.; Gee, N.; Kotrschal, K. Social factors influencing cortisol modulation in dogs during a strange situation procedure. J. Vet. Behavior. 2016, 11, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, E.L.; Gesquiere, L.R.; Gee, N.R.; Levy, K.; Martin, W.L.; Carter, C.S. Effects of affiliative human-animal interaction on dog salivary and plasma oxytocin and vasopressin. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9001:2015; Quality Management Systems—Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/62085.html (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Hare, B.R.A.; Kaminski, J.; Bräuer, J.; Call, J.; Tomasello, M. The domestication hypothesis for dogs’ skills with human communication: A response to Udell et al. (2008) and Wynne et al. (2008). Anim. Behav. 2010, 79, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklosi, A.; Kubinyi, E.; Topal, J.; Gacsi, M.; Viranyi, Z.; Csanyi, V. A simple reason for a big difference: Wolves do not look back at humans, but dogs do. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, J.M.; Bennett, P.C.; Coleman, G.J. A refinement and validation of the Monash Canine Personality Questionnaire (MCPQ). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 116, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratkin, J.L.; Sinn, D.L.; Patall, E.A.; Gosling, S.D. Personality consistency in dogs: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, D.J.; Peters, R.A.; Marston, L.C.; De Groef, B. Investigating canine personality structure using owner questionnaires measuring pet dog behaviour and personality. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 180, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabsits, M.L.J.; Wollein, M. Urodynamic and viscerographic results following short-arm slingplasty. Gynakol. Rundsch. 1988, 28, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Perruolo, G.; Cristiano, S.; Agognon, A.L.; Cabaro, S.; Amato, A.; Dipineto, L.; Borrelli, L.; Formisano, P.; Fioretti, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 affects both humans and animals: What is the potential transmission risk? A literature review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiumana, G.; Botta, D.; Dalla Porta, M.F.; Macchi, S.; Soncini, E.; Santaniello, A.; Paciello, O.; Amicucci, M.; Cellini, M.; Cesaro, S. Consensus statement on animals’ relationship with pediatric oncohematological patients, on behalf of infectious diseases and nurse working groups of the italian association of pediatric hematology-oncology. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerville, R.; O’Connor, E.A.; Asher, L. Why do dogs play? Function and welfare implications of play in the domestic dog. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 197, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faba, L.; Martin-Orue, S.M.; Hulshof, T.G.; Perez, J.F.; Wellington, M.O.; Van Hees, H.M.J. Impact of initial postweaning feed intake on weanling piglet metabolism, gut health, and immunity. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 103, skaf099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz-Bannitz, R.; Ozturk, B.; Cummings, C.; Efthymiou, V.; Casanova Querol, P.; Poulos, L.; Wang, H.; Navarrete, V.; Saeed, H.; Mulla, C.M.; et al. Postprandial metabolomics analysis reveals disordered serotonin metabolism in post-bariatric hypoglycemia. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e180157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Yoon, M. The effects of human-horse interactions on oxytocin and cortisol levels in humans and horses. Animals 2025, 15, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.; Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Chi, J.; Lin, Z.; Smith, G.I.; Klein, S.; Cohen, P.; Rosen, E.D. Control of lipolysis by a population of oxytocinergic sympathetic neurons. Nature 2024, 625, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Watanabe, S.; Takeda, A.K.; Kikusui, T.; Mogi, K.; Nagasawa, M.; Hagihara, K.; Myowa, M. Intestinal microbiome and maternal mental health: Preventing parental stress and enhancing resilience in mothers. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.F.; Yeh, C.Y.; Hsu, S.Y.; Lu, C.H.; Tsai, C.H.; Chiang, P.C.; Weng, H.J.; Tsai, T.F.; Lee, Y.L. Serotonin 2A receptor attenuates psoriatic inflammation by suppressing IL-23 secretion in monocyte-derived Langerhans cells. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.M.M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Soft 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galecki, A.; Burzykowski, T. Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using R; A Step-By-Step Approach; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, A.; Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Team, R.C. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Lin, F.; Chen, L.; Gao, Y. Music therapy in hemodialysis patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2024, 86, 103090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Hsu, Y.J.; Hsu, P.H.; Lee, Y.L.; Lin, C.H.; Lee, M.S.; Chiang, S.L. Effects of intradialytic exercise on dialytic parameters, health-related quality of life, and depression status in hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegarow, P.; Manczak, M.; Rysz, J.; Olszewski, R. The influence of cognitive-behavioral therapy on depression in dialysis patients—Meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, L.F.; Santaniello, A.; Amato, A.; Ceparano, G.; Di Maggio, A.; Sansone, M.; Formisano, P.; Cimmino, I.; Perruolo, G.; Fioretti, A. Changes of oxytocin and serotonin values in dialysis patients after Animal Assisted Activities (AAAs) with a dog-a preliminary study. Animals 2019, 9, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaniello, A.; Garzillo, S.; Cristiano, S.; Fioretti, A.; Menna, L.F. The research of standardized protocols for dog involvement in Animal-Assisted Therapy: A systematic review. Animals 2021, 11, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Basso Ricci, E.; Colombo, E.S. The complexity of the human-animal bond: Empathy, attachment and anthropomorphism in human-animal relationships and animal hoarding. Animals 2022, 12, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merola, I.; Prato-Previde, E.; Marshall-Pescini, S. Social referencing in dog-owner dyads? Anim. Cogn. 2012, 15, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezza, F.; Saturnino, C.; Pizzo, R.; Santaniello, A.; Cristiano, S.; Garzillo, S.; Maldonato, N.M.; Bochicchio, V.; Menna, L.F.; Scandurra, C. Process evaluation of Animal Assisted Therapies with children: The role of the human-animal bond on the therapeutic alliance, depth of elaboration, and smoothness of sessions. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santaniello, A.; Perruolo, G.; Amato, A.; Garzillo, S.; Mormone, F.; Morelli, C.; Formisano, P.; Sansone, M.; Fioretti, A.; Oriente, F. Animal Assisted Activities (AAAs) with Dogs in a Dialysis Center in Southern Italy: Evaluation of Serotonin and Oxytocin Values in Involved Patients. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2944. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122944

Santaniello A, Perruolo G, Amato A, Garzillo S, Mormone F, Morelli C, Formisano P, Sansone M, Fioretti A, Oriente F. Animal Assisted Activities (AAAs) with Dogs in a Dialysis Center in Southern Italy: Evaluation of Serotonin and Oxytocin Values in Involved Patients. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2944. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122944

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantaniello, Antonio, Giuseppe Perruolo, Alessia Amato, Susanne Garzillo, Federica Mormone, Cristina Morelli, Pietro Formisano, Mario Sansone, Alessandro Fioretti, and Francesco Oriente. 2025. "Animal Assisted Activities (AAAs) with Dogs in a Dialysis Center in Southern Italy: Evaluation of Serotonin and Oxytocin Values in Involved Patients" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2944. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122944

APA StyleSantaniello, A., Perruolo, G., Amato, A., Garzillo, S., Mormone, F., Morelli, C., Formisano, P., Sansone, M., Fioretti, A., & Oriente, F. (2025). Animal Assisted Activities (AAAs) with Dogs in a Dialysis Center in Southern Italy: Evaluation of Serotonin and Oxytocin Values in Involved Patients. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2944. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122944