Mass Spectrometry Profiling of Therapeutic Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: m/z Features and Concordance with Immunofixation Electrophoresis †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods

2.2. Patient Samples

3. Results

3.1. Monoclonal Antibody Characterization with EXENT®

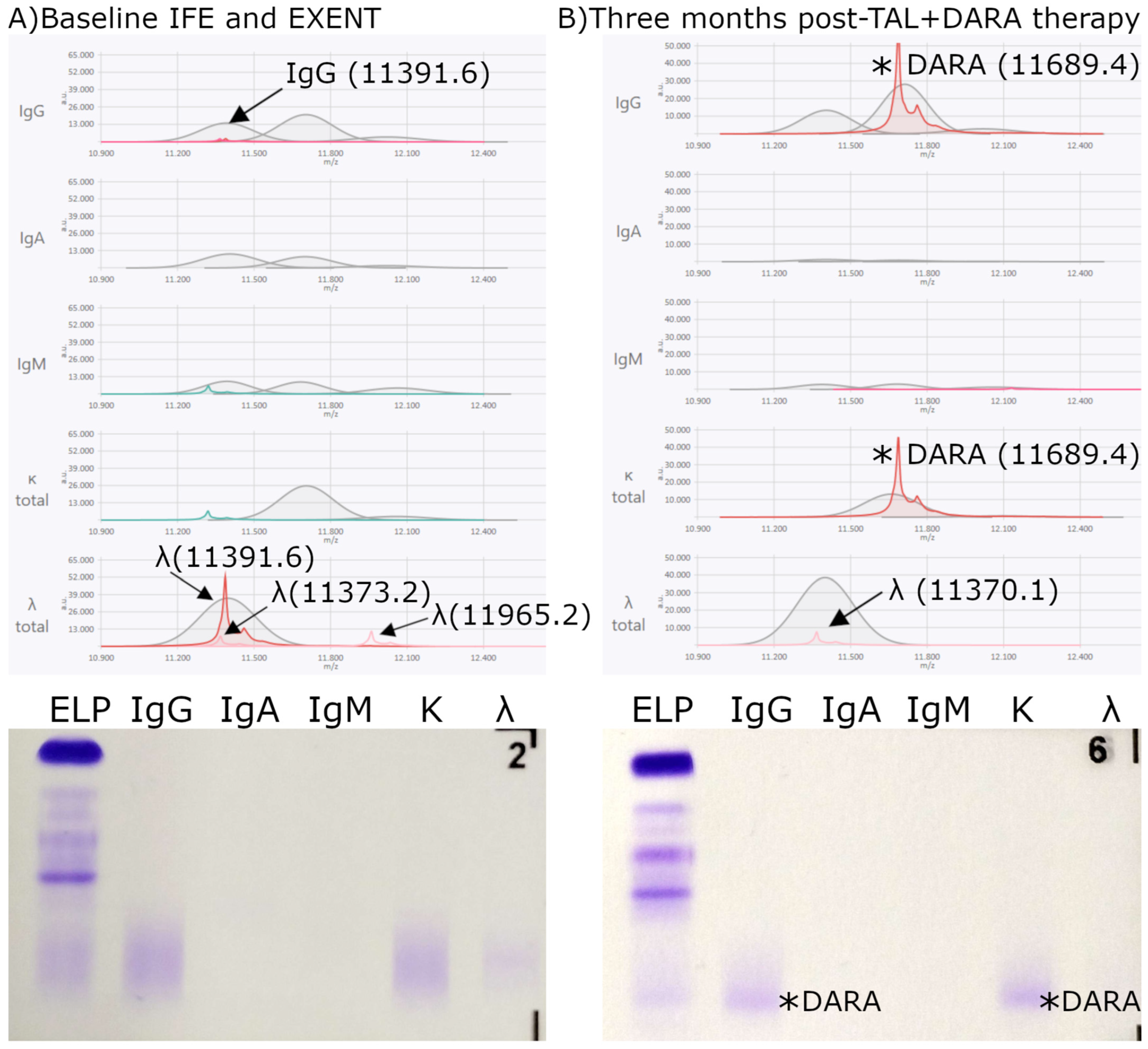

3.2. Analysis of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies in Samples from Treated Patients

3.2.1. Concordance Between EXENT® and IFE

3.2.2. Analysis of Interferences from Monoclonal and Bispecific Antibodies

Patients with Detectable Therapeutic Antibody Interference

Patients Without Detectable Therapeutic Antibody Interference

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cárdenas, M.C.; García-Sanz, R.; Puig, N.; Pérez-Surribas, D.; Flores-Montero, J.; Ortiz-Espejo, M.; de la Rubia, J.; Cruz-Iglesias, E. Recommendations for the study of monoclonal gammopathies in the clinical laboratory. A consensus of the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine and the Spanish Society of Hematology and Hemotherapy. Part I: Update on laboratory tests for the study of monoclonal gammopathies. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2023, 61, 2115–2130. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, M.C.; García-Sanz, R.; Puig, N.; Pérez-Surribas, D.; Flores-Montero, J.; Ortiz-Espejo, M.; De la Rubia, J.; Cruz-Iglesias, E. Recommendations for the study of monoclonal gammopathies in the clinical laboratory. A consensus of the Spanish Society of Laboratory Medicine and the Spanish Society of Hematology and Hemotherapy. Part II: Methodological and clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and follow-up of monoclonal gammopathies. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2023, 61, 2131–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derman, B.A.; Stefka, A.T.; Jiang, K.; McIver, A.; Kubicki, T.; Jasielec, J.K.; Jakubowiak, A.J. Measurable residual disease assessed by mass spectrometry in peripheral blood in multiple myeloma in a phase II trial of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone and autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Paiva, B.; Anderson, K.C.; Durie, B.; Landgren, O.; Moreau, P.; Munshi, N.; Lonial, S.; Bladé, J.; Mateos, M.-V.; et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e328–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicki, T.; Dytfeld, D.; Barnidge, D.; Sakrikar, D.; Przybyłowicz-Chalecka, A.; Jamroziak, K.; Robak, P.; Czyż, J.; Tyczyńska, A.; Druzd-Sitek, A.; et al. Mass spectrometry–based assessment of M protein in peripheral blood during maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. Blood 2024, 144, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Herrera, A.; Sarasquete, M.E.; Jiménez, C.; Puig, N.; García-Sanz, R. Minimal Residual Disease in Multiple Myeloma: Past, Present, and Future. Cancers 2023, 15, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.L.; Puig, N.; Kristinsson, S.; Usmani, S.Z.; Dispenzieri, A.; Bianchi, G.; Kumar, S.; Chng, W.J.; Hajek, R.; Paiva, B.; et al. Mass spectrometry for the evaluation of monoclonal proteins in multiple myeloma and related disorders: An International Myeloma Working Group Mass Spectrometry Committee Report. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.R.; Kohlhagen, M.C.; Willrich, M.A.V.; Kourelis, T.; Dispenzieri, A.; Murray, D.L. A universal solution for eliminating false positives in myeloma due to therapeutic monoclonal antibody interference. Blood 2018, 132, 670–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnidge, D.; Sakrikar, D.; Kubicki, T.; Derman, B.A.; Jakubowiak, A.J.; Lakos, G. Distinguishing Daratumumab from Endogenous Monoclonal Proteins in Serum from Multiple Myeloma Patients Using an Automated Mass Spectrometry System. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2025, 10, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.M.; Cho, S.; Thoren, K.L. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry distinguishes daratumumab from M-proteins. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2019, 492, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devasia, A.J.; Chari, A.; Lancman, G. Bispecific antibodies in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2024, 14, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, V.S.; Davies, A.J. Bispecific antibodies in indolent B-cell lymphomas. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1295599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, H.V.; Karunanithi, K. Performance Characteristics and Limitations of the Available Assays for the Detection and Quantitation of Monoclonal Free Light Chains and New Emerging Methodologies. Antibodies 2024, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Simpson, D.; Ramasamy, K.; Sadler, R. Using quantitative immunoprecipitation mass spectrometry (QIP-MS) to identify low level monoclonal proteins. Clin. Biochem. 2021, 95, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. The EXENT® System—Transforming M-protein Measurement [Internet]. Birmingham, UK: The Binding Site Group Limited (Parte de Thermo Fisher Scientific); 2024 ago. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/bindingsite/gb/en/products/instruments/EXENT-System.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Kawashima, S.; Okuno, Y.; Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, D277–D280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, D.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; Chambers, J.; de Veij, M.; Félix, E.; Magariños, M.P.; Mosquera, J.F.; Mutowo, P.; Nowotka, M.; et al. ChEMBL: Towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D930–D940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, M.R.; Gasteiger, E.; Bairoch, A.; Sanchez, J.C.; Williams, K.L.; Appel, R.D.; Hochstrasser, D.F. Protein identification and analysis tools in the ExPASy server. Methods Mol. Biol. 1999, 112, 531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Amin Nordin, F.D.; Mohd Khalid, M.K.N.; Abdul Aziz, S.M.; Mohamad Bakri, N.A.; Ahmad Ridzuan, S.N.; Abdul Jalil, J.; Habib, A.; Yakob, Y. Performance comparison of EasyFix G26 and HYDRASYS 2 SCAN for the detection of serum monoclonal proteins. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2020, 34, e23254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment Reports (EPAR)—Product Information for Centrally Authorized Monoclonal Antibodies [Internet]. Amsterdam: EMA. 2025. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Mills, J.R.; Kohlhagen, M.C.; Dasari, S.; Vanderboom, P.M.; Kyle, R.A.; Katzmann, J.A.; Willrich, M.A.; Barnidge, D.R.; Dispenzieri, A.; Murray, D.L. Comprehensive Assessment of M-Proteins Using Nanobody Enrichment Coupled to MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2016, 62, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveillard, M.; Korde, N.; Ciardiello, A.; Diamond, B.; Lesokhin, A.; Mailankody, S.; Smith, E.; Hassoun, H.; Hultcrantz, M.; Shah, U.; et al. Using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in peripheral blood for the follow up of newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with daratumumab-based combination therapy. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2021, 516, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevejan, L.; Schauwvlieghe, A.; Van Droogenbroeck, J.; Langlois, M.; Bossuyt, X.; Vercammen, M. Interference of bispecific antibodies on serum M-protein analysis with EXENT® mass spectrometry. In Proceedings of the EuroMedLab 2025—26th IFCC-EFLM European Congress of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, Brussels, Belgium, 18 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, N.; Murray, D.; Dispenzieri, A.; Kapoor, P.; Gertz, M.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Hayman, S.R.; Buadi, F.K.; Gonsalves, W.; Muchtar, E.; et al. Tracking daratumumab clearance using mass spectrometry: Implications on M protein monitoring and reusing daratumumab. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1426–1428, Erratum in Leukemia 2022, 36, 1449; Leukemia 2024, 38, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agulló, C.; Puig, N.; Varo, N.; Iglesias, M.Á.; Mugueta, C.; Pello, R.; Paiva, B.; Martínez-López, J.; Castro, S.; Cárdenas, M.C.; et al. Recommendations for the study of monoclonal gammopathies in the clinical laboratory. A consensus of the Spanish society of laboratory medicine and the Spanish society of hematology and hemotherapy. Part III: Clinical and analytical recommendations for the study of monoclonal gammopathies by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, N.; Agulló, C.; Contreras, T.; Cedena, M.-T.; Martínez-López, J.; Oriol, A.; Blanchard, M.-J.; Ríos, R.; Íñigo, M.-B.; Sureda, A.; et al. Measurable residual disease by mass spectrometry and next-generation flow to assess treatment response in myeloma. Blood 2024, 144, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, N.; Agulló, C.; Contreras, T.; Pérez, J.-J.; Aires, I.; Calasanz, M.J.; García-Sanz, R.; Castro, S.; Martínez-López, J.; Rodríguez-Otero, P.; et al. Single-point and kinetics of peripheral residual disease by mass spectrometry to predict outcome in patients with high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma included in the GEM-CESAR trial. Haematologica 2024, 109, 4056–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, N.; Contreras, M.T.; Agulló, C.; Martínez-López, J.; Oriol, A.; Blanchard, M.-J.; Ríos, R.; Martín, J.; Iñigo, M.-B.; Sureda, A.; et al. Mass spectrometry vs immunofixation for treatment monitoring in multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 3234–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, E.K.; Huhn, S.; Miah, K.; Poos, A.M.; Scheid, C.; Weisel, K.C.; Bertsch, U.; Munder, M.; Berlanga, O.; Hose, D.; et al. Implications and prognostic impact of mass spectrometry in patients with newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2023, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pello Gutiérrez, R.; Iglesias De La Puente, M.Á.; Mateos Pablos, R.; Barbosa, N.; Díaz-Tejedor, A.; Martínez López, J.; López Jiménez, E.A. Distinguishing Monoclonal Proteins from Therapeutic Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma Using Mass Spectrometry. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2025, 63, s1048–s1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pello, R.; Cedena, M.T.; Iglesias, M.Á.; Vidal, R.; Mateos, R.; Blanco, A.; López, M.N.; García, Á.; Miras Calvo, F.; Alonso, R.; et al. Mass Spectrometry Enables Precise Monitoring of Bispecific Antibody Therapy in Multiple Myeloma; Abstract PF713; 4160120; EHA Library: Milan, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Bispecific t-mAb Therapies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM Isotype | Total | ETEN | LINVO | TEC | TAL + DARA | TEC + TAL | ELRA |

| IgGκ | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | |||

| IgGλ | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||

| IgAκ | 4 | 4 | |||||

| IgAλ | 4 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| BJ κ | 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| BJ λ | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Monoclonal Antibody | Theoretical m/z | Measured m/z | Isotype | Target | Cmax (µg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monospecific | MM | Daratumumab | 11,692.0 | 11,691.1 ± 0.1 | IgGK | Anti CD38 | 132–780 (SC)/256–688 (IV) |

| Isatuximab | 11,745.1 | 11,744.5 ± 0.4 | IgGK | Anti CD38 | 351 | ||

| Elotuzumab | 11,713.5 | 11,713.4 ± 0.3 | IgGK | Anti SLAMF7 | 217–226 | ||

| Belantamab | 11,816.2 | 11,815.4 ± * | IgGK | Anti BCMA | 43 | ||

| Lymph | Rituximab | 11,528.3 | 11,519.7 ± 0.4 | IgGK | Anti CD20 | 157–404 | |

| Brentuximab vedotin | 11,864.1 | 11,864.2 ± 0.5 | IgGK | Anti CD30 | 31.98 | ||

| Bispecific | MM | Elranatamab | 11,812.2 | 11,811.5 ± 0.3 | IgGK | Anti BCMA | 20.1–33.6 |

| 12,050.4 | 12,049.6 ± 0.2 | IgGK | Anti CD3 | ||||

| Teclistamab | 11,312.2 | 11,302.9 ± 0.4 | IgGL | Anti CD3 | |||

| 11,318.0 | 11,317.6 ± 0.6 | IgGL | Anti BCMA | 23.8–25.3 | |||

| Linvoseltamab | 11,709.0 | 11,708.4 ± 0.8 | IgGK | Anti CD3 BCMA | 64.8–124 | ||

| Etentamig | 11,697.0 | 11,695.6 ± 0.1 | IgGK | Anti CD3 BCMA | 100–200 | ||

| Talquetamab | 11,312.2 | 11,303.3 ± 0.1 | IgGKL | Anti CD3 | 1.6–3.8 | ||

| 11,820.6 | 11,820.4 ± 0.1 | IgGKL | Anti GPRC5D | ||||

| Lymph | Epcoritamab | 11,311.7 | 11,301.7 ± 0.5 | IgGKL | Anti CD3 | 4.76–11.1 | |

| 11,721.0 | 11,719.3 ± 0.5 | IgGKL | Anti CD20 | ||||

| Odronextamab | 11,629.0 | 11,628.1 ± 0.2 | IgGK | Anti CD3 Anti CD20 | 0.024–0.196 | ||

| Mosunetuzumab | 11,618.9 | 11,617.9 ± 0.4 | IgGK | Anti CD20 | 17.9 | ||

| 12,068.0 | 12,066.6 ± 0.5 | IgGK | Anti CD3 |

Detectable: t-mAbs with Cmax ≥ 15 µg/mL.

Detectable: t-mAbs with Cmax ≥ 15 µg/mL.  Not detectable: t-mAbs with Cmax < 15 µg/mL. MM: multiple myeloma; Lymph: lymphomas; SLAMF7: Signaling Lymphocytic Activation Molecule Family member 7; BCMA: B-cell maturation antigen; SC: subcutaneous; IV: intravenous.

Not detectable: t-mAbs with Cmax < 15 µg/mL. MM: multiple myeloma; Lymph: lymphomas; SLAMF7: Signaling Lymphocytic Activation Molecule Family member 7; BCMA: B-cell maturation antigen; SC: subcutaneous; IV: intravenous.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pello, R.; Iglesias, M.Á.; Vidal, R.; Mateos, R.; Outón, M.; Agulló, C.; Varo, N.; Blanco-Sánchez, A.; López-Muñoz, N.; García, Á.; et al. Mass Spectrometry Profiling of Therapeutic Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: m/z Features and Concordance with Immunofixation Electrophoresis. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2933. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122933

Pello R, Iglesias MÁ, Vidal R, Mateos R, Outón M, Agulló C, Varo N, Blanco-Sánchez A, López-Muñoz N, García Á, et al. Mass Spectrometry Profiling of Therapeutic Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: m/z Features and Concordance with Immunofixation Electrophoresis. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2933. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122933

Chicago/Turabian StylePello, Rosa, María Ángeles Iglesias, Raúl Vidal, Raúl Mateos, Marta Outón, Cristina Agulló, Nerea Varo, Alberto Blanco-Sánchez, Nieves López-Muñoz, Álvaro García, and et al. 2025. "Mass Spectrometry Profiling of Therapeutic Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: m/z Features and Concordance with Immunofixation Electrophoresis" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2933. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122933

APA StylePello, R., Iglesias, M. Á., Vidal, R., Mateos, R., Outón, M., Agulló, C., Varo, N., Blanco-Sánchez, A., López-Muñoz, N., García, Á., Miras, F., Iñiguez, R., Gil-Alós, D., Alonso, R., López, E. A., Martínez-López, J., & Cedena, M. T. (2025). Mass Spectrometry Profiling of Therapeutic Antibodies in Multiple Myeloma: m/z Features and Concordance with Immunofixation Electrophoresis. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2933. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122933