1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a substantial clinical and organizational burden across Eastern Europe, with Romania persistently reporting among the highest notification rates in the EU/EEA and a marked concentration of disease in vulnerable groups (e.g., people experiencing homelessness, people who use drugs, and those in prisons) [

1]. Spatial analyses further suggest heterogeneity in incidence and clustering across Romanian counties, shaped by air pollution and socio-economic gradients, underscoring the need for service models that respond to local epidemiology and surging capacity demands [

2]. Within hospital systems, TB admissions are non-trivial contributors to bed occupancy, and Romanian and neighboring health systems have been evaluating shifts from hospital-centric to ambulatory-first care to decompress inpatient units without compromising outcomes [

3]. Nevertheless, in-hospital mortality for TB persists—regional cohorts from south-eastern Romania documented measurable inpatient fatality risk, often concentrated early after admission—highlighting a window where timely risk-stratification could alter trajectories [

4].

At the bedside, simple physiological signals—oxygen saturation (SpO

2) and respiratory rate—capture cardiopulmonary strain quickly and inexpensively. Across diverse TB cohorts, early decompensation is frequently heralded by tachypnea and hypoxemia; prediction efforts for inpatient mortality consistently elevate these markers as high-yield features [

5,

6]. Even outside explicit acute respiratory failure, chronic or persistent hypoxemia among hospitalized adults with TB is common and portends adverse outcomes, reinforcing the salience of pulse oximetry-informed care pathways [

7]. These observations motivate physiology-anchored early warning strategies in TB wards.

Inflammation is the second pillar. C-reactive protein (CRP) has been repeatedly linked to bacillary burden and disease activity, and serial CRP declines during early treatment, correlating with clinical response and risk of adverse events, suggesting prognostic value beyond diagnosis alone [

8]. While CRP has been evaluated as a triage/screening tool with mixed performance across populations and settings, its biologic responsiveness to treatment makes it attractive for short-horizon monitoring once TB is diagnosed or strongly suspected [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Beyond single analytes, composite cell-count indices derived from the complete blood count—such as the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII)—track myeloid–lymphoid balance and have shown associations with PTB severity, cavity formation, and acute-phase activation, offering analytically cheap surrogates of inflammatory tone [

15].

Nutrition is the third, deeply interwoven axis. Malnutrition is highly prevalent at TB presentation and is independently associated with worse treatment outcomes, slower culture conversion, and higher mortality; meta-analytical evidence reinforces an inverse relationship between body mass index (BMI) and TB risk and outcomes [

11,

12]. In the inpatient setting, serum albumin—reflecting both nutritional reserve and inflammation-driven redistribution—has repeatedly predicted in-hospital death among adults with TB, even after adjustment for age and comorbidities [

13,

14]. Together, BMI and albumin provide complementary information about energy stores and visceral protein status that is immediate to clinical decision-making. These three domains are tightly interconnected: systemic inflammation can worsen respiratory mechanics and gas exchange through parenchymal injury and immunothrombosis, while the resulting catabolic drive and anorexia aggravate malnutrition, which in turn impairs immune function and respiratory muscle performance. Existing TB risk-stratification tools have largely focused on cross-sectional symptoms and signs or single-timepoint laboratory tests, with limited integration of these interacting axes and minimal incorporation of early dynamic biomarkers that capture treatment response trajectories.

A limitation of most ward-level risk assessments is their static nature—estimating prognosis from admission snapshots while early clinical courses diverge. In TB, meaningful physiologic and inflammatory changes often emerge over the first days of therapy (e.g., improving oxygenation, down-trending CRP, stabilizing vital signs), whereas non-responders remain inflamed, hypoxemic, and catabolic [

5,

8,

9,

10]. Capturing these short-horizon trajectories may refine discrimination between improving and non-improving phenotypes and identify patients who warrant escalation, nutrition-first bundles, or closer monitoring.

Against this backdrop, we conceptualized a pragmatic composite—the TRIAD-TB score—that integrates three routinely accessible domains at admission (physiology, inflammation, nutrition) and augments them with 72 h deltas in CRP and albumin. The approach leverages ubiquitous ward data (vital signs, CBC-derived indices, CRP, albumin, BMI) rather than specialized cytokine panels, aiming for immediate implementability in resource-constrained TB units [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. We selected a 72 h window because prior work shows that CRP can decline substantially over the first 2–3 days of effective TB therapy, and early changes in albumin often accompany shifts in inflammatory tone and fluid balance [

8,

10]. We hypothesized that (i) higher TRIAD-TB scores would associate with greater 30-day mortality and longer length of stay; (ii) TRIAD-TB would outperform domain-specific comparators built from physiology-only (SpO

2, RR), inflammation-only (CRP, SII), or nutrition-only (BMI, albumin) inputs; and (iii) incorporating 72 h deltas would add incremental discrimination beyond baseline values alone.

3. Results

The cohort was predominantly male (100/126, 79.4%) and current smokers were frequent (93/126, 73.8%). The mean age was 51.1 ± 14.9 years and BMI averaged 21.6 ± 3.5 kg/m

2, with 26.2% underweight and 18.3% overweight/obese. MDR-TB prevalence was 12.7%. Physiologic stress at presentation was notable: mean SpO

2 on room air was 93.8 ± 2.9%, respiratory rate was 22.1 ± 4.3/min, and heart rate was 96.7 ± 14.2/min. Inflammatory and nutritional markers indicated high disease activity and limited reserves (CRP 74.3 ± 38.6 mg/L; SII 1.5 ± 0.8 × 10

6/µL; albumin 35.1 ± 5.7 g/L), as seen in

Table 1.

Higher TRIAD-TB severity tracked with worse physiology, greater inflammation, and poorer nutrition. From the low → high tertile, SpO

2 fell from 95.1 ± 2.2% to 92.4 ± 2.6% (Δ −2.7%,

p < 0.001) and respiratory rate rose from 20.3 ± 3.6 to 24.1 ± 4.2/min (Δ +3.8/min,

p < 0.001). CRP increased from 55.8 ± 28.4 to 93.2 ± 40.1 mg/L (Δ +37.4 mg/L,

p < 0.001) and SII from 1.1 ± 0.5 to 1.9 ± 0.9 × 10

6/µL (Δ +0.8 × 10

6/µL,

p < 0.001). Nutritional indices were progressively worse (BMI 22.6 ± 3.4 → 20.6 ± 3.5 kg/m

2,

p = 0.012; albumin 37.4 ± 5.0 → 32.8 ± 5.6 g/L,

p = 0.001), supporting a coherent gradient across domains (

Table 2). Because TRIAD-TB tertiles are constructed directly from these same physiologic, inflammatory, and nutritional inputs, the presence of a monotonic gradient across tertiles is mathematically expected and should be interpreted primarily as the internal consistency of the composite rather than independent biological validation.

Early treatment dynamics diverged by baseline severity. The CRP ratio (72 h/0 h) worsened stepwise from 0.62 ± 0.18 in the low tertile to 0.89 ± 0.24 in the high tertile (

p < 0.001), indicating blunted inflammatory resolution with increasing severity. Albumin rose slightly in low severity (Δ +0.7 ± 1.3 g/L) but declined in high severity (Δ −0.6 ± 1.6 g/L;

p < 0.001). Similarly, SII improved in low severity (ratio 0.78 ± 0.22) but increased in high severity (1.03 ± 0.27;

p = 0.002) (

Table 3). 72 h CRP and albumin measurements were protocolized for all participants, whereas 72 h CBC with differential to calculate SII was missing in eight cases;

Table 3 therefore reports complete-case trajectories for the 118 patients with available 0 h and 72 h SII. Reasons for missing 72 h SII were not systematically recorded and likely reflect a mixture of early discharge, logistic constraints, and early deterioration; accordingly, these dynamic analyses should be interpreted as exploratory.

Adverse outcomes increased monotonically with severity. Thirty-day mortality rose from 1/42 (2.4%) in the low tertile to 7/42 (16.7%) in the high tertile (≈7-fold increase;

p = 0.018). Mean length of stay lengthened by 7.4 days (24.7 ± 5.8 → 32.1 ± 7.3;

p < 0.001). ICU admission climbed from 7.1% to 28.6% (

p = 0.012), and time to smear conversion was prolonged by 8.4 days (26.3 ± 8.1 → 34.7 ± 9.4;

p < 0.001), as presented in

Table 4.

TRIAD-TB correlated moderately with longer hospitalization (ρ = 0.46,

p < 0.001) and with 30-day mortality on the point-biserial scale (ρ = 0.32,

p < 0.001). A lower admission of SpO

2 related to a longer LOS (ρ = −0.39,

p < 0.001), while a higher respiratory rate correlated with mortality (ρ = 0.28,

p = 0.002). Early inflammatory and nutritional dynamics were informative: a higher CRP ratio associated with mortality (ρ = 0.29,

p = 0.001) and increases in albumin over 72 h related to a shorter LOS (ρ = −0.33,

p < 0.001). SII also tracked with LOS (ρ = 0.31,

p < 0.001), and lower BMI modestly predicted longer stays (ρ = −0.22,

p = 0.013), as seen in

Table 5.

After multivariable adjustment, each SD increase in TRIAD-TB was associated with more than double the odds of 30-day death (adjusted OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.3–4.8;

p = 0.006). Age (per 10 years; OR 1.3, 0.9–1.8;

p = 0.121), male sex (OR 1.1, 0.4–3.1;

p = 0.84), diabetes (OR 1.6, 0.5–4.7;

p = 0.388), and MDR-TB (OR 1.9, 0.7–5.3;

p = 0.204) did not reach conventional statistical significance in this low-event sample; however, their point estimates were directionally consistent with the prior literature, and the wide confidence intervals suggest limited power rather than an absence of effect. Within this context, TRIAD-TB emerged as an independent predictor of 30-day mortality (

Table 6) but should not be interpreted as supplanting established risk factors.

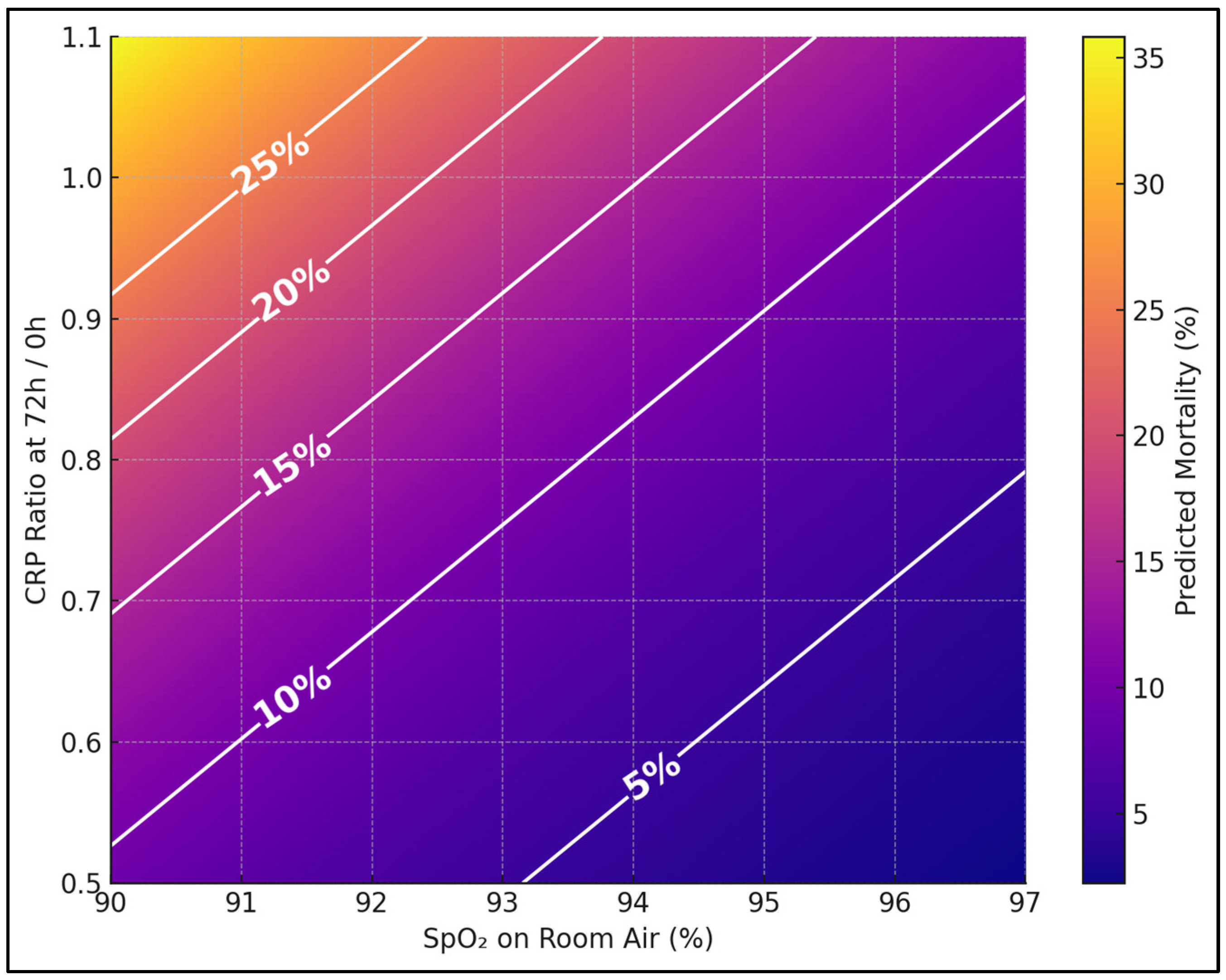

Figure 1 shows predicted 30-day mortality (%) across a clinically realistic grid of admission SpO

2 (90–97%) and early CRP trajectory (72 h/0 h = 0.5–1.1), with other TRIAD-TB components held at cohort means. Iso-risk contours (5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%) make bedside thresholds obvious—e.g., patients at SpO

2 92% with CRP ratio 0.95 sit near the 15–20% band, signaling urgent escalation even if vitals are only modestly abnormal.

TRIAD-TB independently predicted longer hospitalization: per SD-increase, LOS rose by 19% (adjusted IRR 1.19, 95% CI 1.09–1.30;

p < 0.001). Underweight status conferred a modest excess LOS vs. normal BMI (IRR 1.12, 1.01–1.25;

p = 0.039), whereas overweight/obesity showed a nonsignificant trend toward shorter stays (IRR 0.93, 0.84–1.02;

p = 0.091). Age, diabetes, and MDR-TB were not significant predictors in this model (all

p > 0.10), as seen in

Table 7.

The full TRIAD-TB model achieved superior discrimination for 30-day mortality (AUC 0.84, 95% CI 0.75–0.92) with better overall accuracy (Brier 0.067) and near-ideal calibration (slope 0.96), and explained 21.8% of deviance for LOS. This outperformed physiology-only (AUC 0.72; Brier 0.091), inflammation-only (AUC 0.69; Brier 0.098), and nutrition-only (AUC 0.66; Brier 0.104) comparators. A pragmatic “mini-TRIAD” using admission-only inputs retained strong discrimination (AUC 0.79, 95% CI 0.69–0.88; Brier 0.079) and good calibration (0.93), suggesting feasible deployment when 72 h deltas are unavailable (

Table 8). The 30-day mortality rate in the cohort was 8.7% (11/126), which provides context for the low Brier scores observed.

Figure 2 translates the LOS IRR into planning terms by estimating bed-days per 100 admissions across TRIAD-TB deciles (low → high risk). The top two deciles consume ~24.9% of bed-days (11.9% + 13.0%), quantifying how targeted protocols for the highest-risk patients can free capacity fastest. Percent share labels (one decimal) are printed above each bar for quick use in ward huddles.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Findings

The composite TRIAD-TB construct—integrating physiology, inflammation, and nutrition with short-horizon deltas—aligned with and extended prior tuberculosis (TB) severity instruments that were built chiefly from symptoms and single-timepoint variables. Earlier clinical scores such as the Bandim TBscore and TBscore II predicted adverse outcomes using symptom/functional domains but did not leverage early biomarker dynamics, limiting responsiveness to the first days of treatment when trajectories begin to diverge [

29,

30]. More recent models, including the TREAT rule and externally validated prognostic scores derived from routine hospital data, similarly focused on admission covariates without capturing near-term change [

31,

32]. By comparison, adding 72 h CRP and albumin shifts in TRIAD-TB improved discrimination relative to admission-only comparators, a direction consistent with contemporary work showing that parsimonious, objective items such as hypoxemia and lymphocyte counts (AHL score) materially stratified in-hospital mortality risk but still relied on baseline status [

33]. In contrast, TRIAD-TB explicitly incorporates early 72 h changes in CRP and albumin, thereby adding a temporal dimension that reflects initial treatment response rather than relying solely on cross-sectional burden at admission. This dynamic specification aligns with the clinical observation that trajectories over the first few days often distinguish improving from non-improving phenotypes more clearly than baseline measurements alone.

Physiologic stress captured by oxygenation and ventilatory drive emerged as a dominant axis, in keeping with the literature from severe TB cohorts. Hypoxemia formed a core element of the AHL score and robustly separated risk groups in prospective development and validation cohorts [

33]. Historical ICU series reported high mortality among patients requiring invasive support, underscoring how tachypnea–hypoxemia syndromes track with decompensation; in active pulmonary TB needing mechanical ventilation, case fatality was substantial and increased with gas-exchange derangements and multiorgan strain [

34,

35,

36]. In the present cohort, lower SpO

2 and a higher respiratory rate correlated with death and longer hospital stay, consistent with these data and reinforcing the use of simple bedside physiology as a high-yield signal embedded within composite prediction.

Inflammation constituted the second pillar. Prior work showed that baseline CRP varied with host and mycobacterial factors and reflected disease activity, while systemic inflammatory profiles (including CRP and cytokines) associated with radiographic severity and bacillary burden [

37,

38]. Longitudinal studies further demonstrated that incomplete early CRP decline related to persistent culture positivity later in the intensive phase, suggesting that early trajectories carry prognostic information beyond static levels [

39]. In elderly pulmonary TB, higher CRP associated with delayed smear conversion, adding a clinically practical bridge between inflammatory tone and time to microbiologic response [

40]. The graded increase in 30-day mortality with higher CRP ratio (72 h/0 h) replicated these patterns, supporting short-horizon CRP kinetics as an actionable monitor of treatment response and risk.

The nutritional axis exhibited expected and clinically meaningful effects. Population-based analyses linked underweight status to higher all-cause and TB-specific mortality during treatment, with the strongest effects at the lowest BMI strata and within early death windows [

41,

42,

43]. Albumin, while influenced by inflammation (negative acute-phase behavior), consistently functioned as a pragmatic severity and outcome marker across infectious and critical illness contexts; in HIV-associated TB cohorts, hypoalbuminemia predicted death and tracked with disease activity, supporting its dual informative role in energy reservation and inflammatory redistribution [

44]. In this study, lower baseline BMI and albumin—and especially the failure of albumin to rise in the first 72 h—related to prolonged length of stay, mirroring the synergy between catabolic load and inflammatory drive described in prior work.

Early microbiologic dynamics provided an external validity check for the inflammatory and physiologic signals. Multiple cohorts identified factors for delayed smear/culture conversion—older age, higher baseline bacillary load, cavitary disease, diabetes, and extensive radiographic involvement—features that overlapped with higher TRIAD-TB strata [

45,

46,

47]. Reports also connected higher CRP with delayed conversion in older adults, again aligning with this study’s observation that blunted early CRP improvement tracked with worse outcomes and longer hospitalization [

40,

45]. The concordance across physiologic, inflammatory, nutritional, and microbiologic trajectories suggested that the composite captured a coherent “non-improving” phenotype that has been repeatedly associated with the failure to convert and with downstream morbidity.

The concordance between inflammatory and nutritional trajectories and microbiologic response raises the possibility that simple biologic markers such as serial CRP and albumin could serve as pragmatic surrogate endpoints for microbiologic improvement in future trials or treatment-monitoring protocols. In settings where frequent sputum culture or advanced imaging is not feasible, integrating these trajectories into risk scores such as TRIAD-TB may provide an accessible bridge between host response and pathogen clearance.

Finally, the operational implications of risk concentration were consistent with prior experiences implementing simple TB risk tools for triage and escalation. Studies showed that brief, objective models stratified inpatient risk and could help target enhanced monitoring or bundled interventions to patients most likely to die or to consume disproportionate bed-days [

31,

32,

33]. The concentration of bed-days in the highest TRIAD-TB deciles in this cohort closely paralleled such experiences, indicating that embedding admission-plus-72 h reassessment in ward huddles and care pathways could enable earlier escalation, nutrition-first strategies, and improved discharge planning in settings with constrained capacity. A further operational consideration is how TRIAD-TB relates to generic early warning scores such as NEWS or MEWS, which are widely implemented across acute-care wards. In this derivation study, we could not reconstruct these scores reliably, because several components were either not routinely recorded or were incompletely documented. As such, TRIAD-TB should be viewed as a TB-focused complement to, rather than a replacement for, generic EWS, and formal benchmarking against NEWS/MEWS and other ward-level tools is a key priority for future external validation studies.

Importantly, the reported superiority of the full TRIAD-TB model over single-domain comparators is demonstrated under this equal-weight, pragmatic specification. The relative prognostic contribution of each component may differ in larger or more diverse cohorts, and future work should explore penalized approaches (e.g., LASSO, elastic net) and cross-validated weighting schemes to test the robustness and potential optimization of the composite. Regarding the implications for clinical practice, TRIAD-TB offers a pragmatic, bedside-ready way to identify pulmonary TB inpatients at the highest short-term risk using data every ward already collects (vitals, CBC-derived SII, CRP, BMI, albumin) and their 72 h trajectories. In our cohort, risk rose stepwise across tertiles—30-day mortality from 2.4% to 16.7% and mean LOS from 24.7 ± 5.8 to 32.1 ± 7.3 days—while the full model discriminated well (AUC 0.84; Brier 0.067), and a same-day “mini-TRIAD” retained strong performance when deltas were unavailable (AUC 0.79). Clinically, this supports a two-timepoint strategy: (i) admission triage with the mini-TRIAD to trigger closer monitoring, early ICU outreach, and nutrition consults for high-risk patients; and (ii) a scheduled day-3 “re-stratification” using the full TRIAD-TB, incorporating CRP ratio and albumin change, to detect non-responders and prompt escalation (repeat imaging, search for complications, expedited DST/MDR evaluation, adherence/toxicity checks) and proactive discharge planning.

4.2. Study Limitations and Future Implications

This was a two-center Romanian cohort of culture-confirmed pulmonary TB that deliberately excluded adults with HIV co-infection and chronic systemic immunosuppression. As a result, TRIAD-TB is currently supported only in HIV-negative, non-immunosuppressed adults hospitalized with pulmonary TB in similar Eastern European health-system contexts, and its performance in high HIV-burden settings or in patients with other forms of profound immunosuppression remains unknown and requires dedicated validation. Required 72 h labs introduce potential survivorship and availability bias (early deaths/missing draws), and measurement heterogeneity across platforms may affect SII/CRP/albumin comparability. We did not systematically incorporate radiographic severity, smear grade, or comprehensive socio-economic determinants, nor did we benchmark against widely used generic early warning scores. Also, although we compared TRIAD-TB with physiology-only, inflammation-only, and nutrition-only models derived from the same dataset, we were unable to benchmark its performance against widely used generic early warning scores (NEWS, MEWS) because these were not prospectively captured in a reconstructable form. This gap limits immediate operational comparability and underscores the need for external validation cohorts in which generic EWSs are recorded alongside TB-specific composites. By design, TRIAD-TB is defined as an equal-weight sum of z-standardized predictors. While this facilitates parsimony and reduces the risk of overfitting in a modest sample, it also means that the raw scale is not directly portable, and it implicitly assumes that each domain contributes equally to risk. External implementation will require either re-standardization to local distributions or the development of a more intuitive, integer points-based version with weights estimated and calibrated in larger, independent cohorts. In addition, although both participating laboratories followed routine quality assurance procedures, we did not undertake bespoke cross-platform harmonization, so some of the observed raw value gradients may partially reflect center-level assay differences rather than purely biological variation. Moreover, the inclusion of adults who had already received up to seven days of anti-tuberculosis therapy before baseline sampling may have attenuated or distorted admission CRP and albumin levels, as these markers can change rapidly with treatment and fluid balance; we were underpowered to perform robust stratified analyses by treatment duration, and this potential confounding should be considered when interpreting the inflammatory and nutritional gradients. Finally, model thresholds were illustrated but not prospectively tested as actionable triggers.

Beyond these limitations, future work should focus on the prospective, multicenter validation of TRIAD-TB in high-burden settings (including those with substantial HIV co-infection), on implementation studies evaluating its impact when embedded as a real-time decision-support tool, and on digital extensions that allow continuous risk updating as new data accrue during hospitalization. Such efforts, ideally combining TRIAD-TB with generic early warning scores and leveraging penalized or machine-learning approaches in larger datasets, will be necessary to refine thresholds, update calibration, and confirm clinical utility.