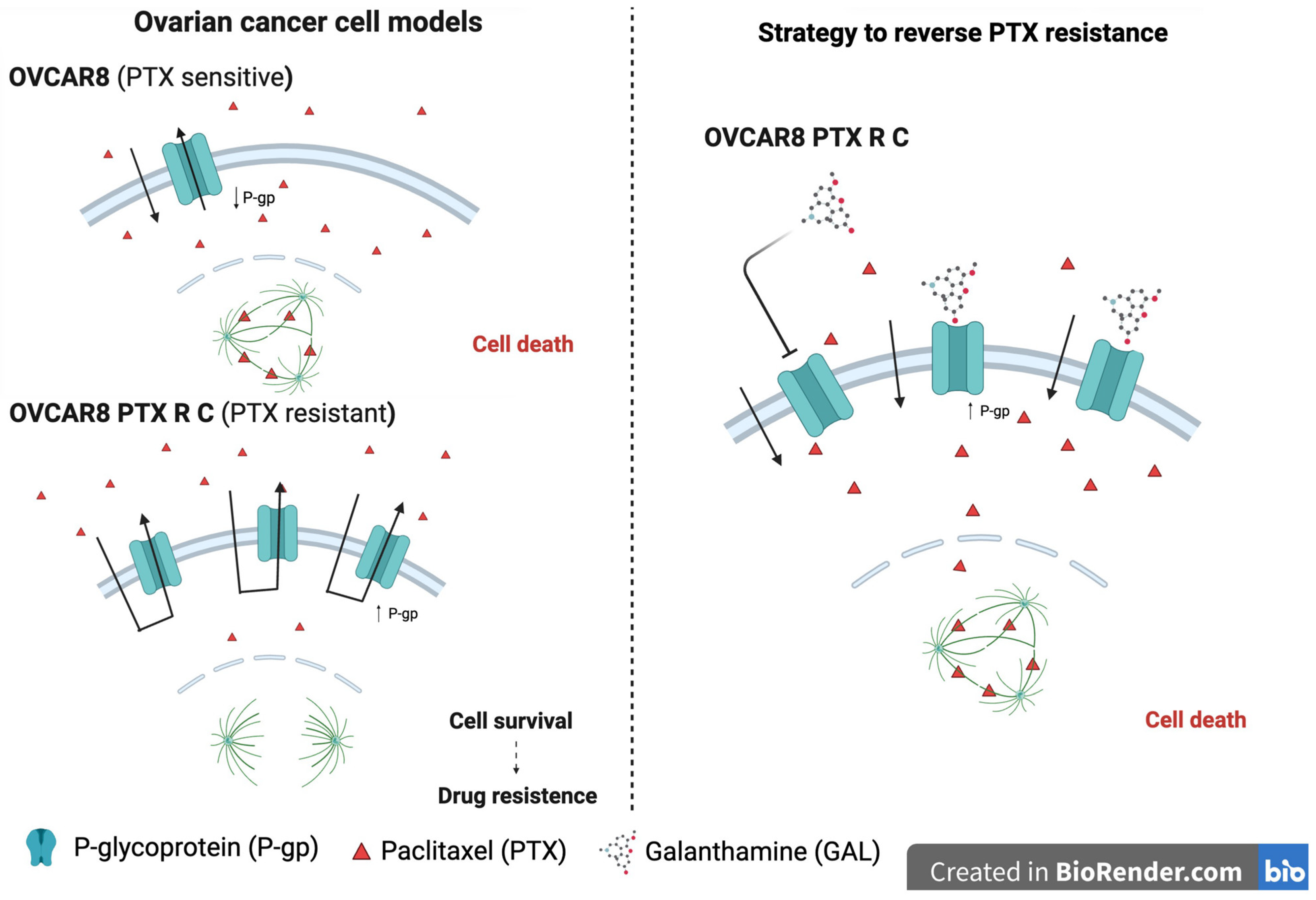

Galanthamine Fails to Reverse P-gp-Mediated Paclitaxel Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

2.2. Drugs

2.3. Cell Viability

2.4. Drug Interaction Analysis

2.5. Immunocytochemistry

2.6. Rhodamine-123 Accumulation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

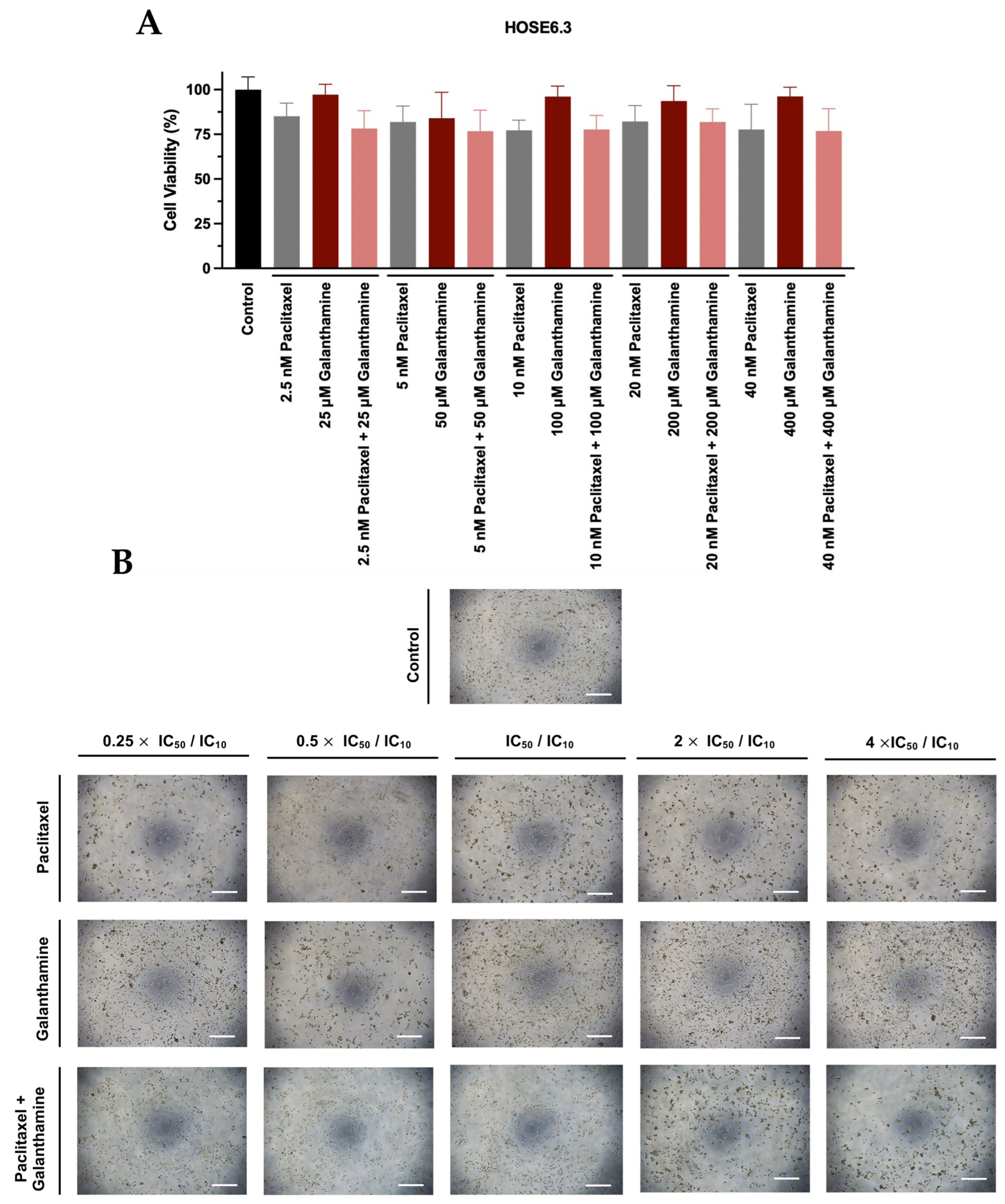

3.1. Galanthamine Does Not Demonstrate an Effect on Cellular Viability of Chemoresistant High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cell Lines

3.2. The Combination of Paclitaxel with Galanthamine Does Not Demonstrate Efficacy in Reducing Cellular Viability of Chemoresistant High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cell Lines

3.3. Combining Paclitaxel with Galanthamine Does Not Demonstrate a Synergistic Effect on Chemoresistant High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cell Lines

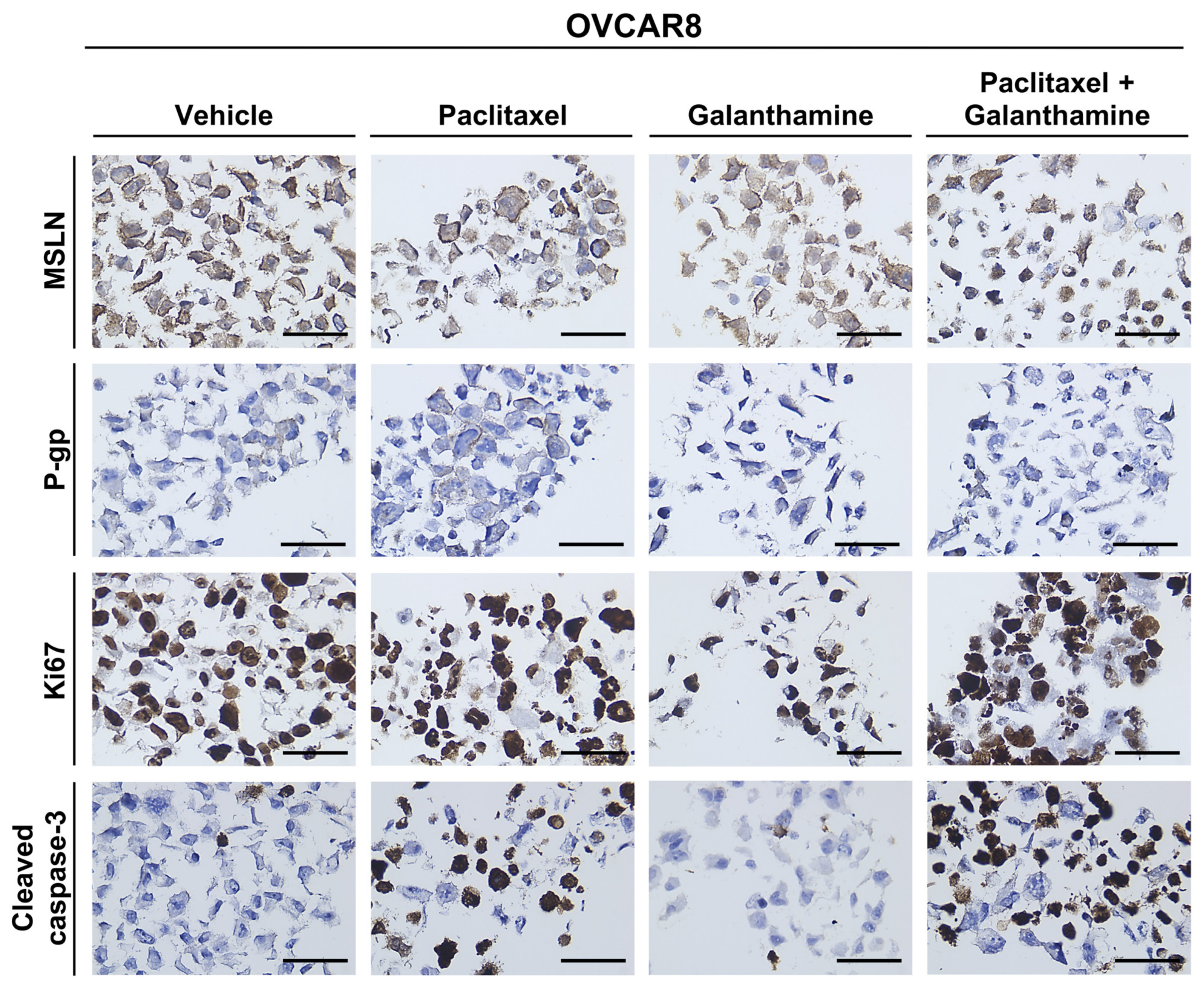

3.4. Galanthamine Treatment Does Not Influence the Phenotype of High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cell Lines

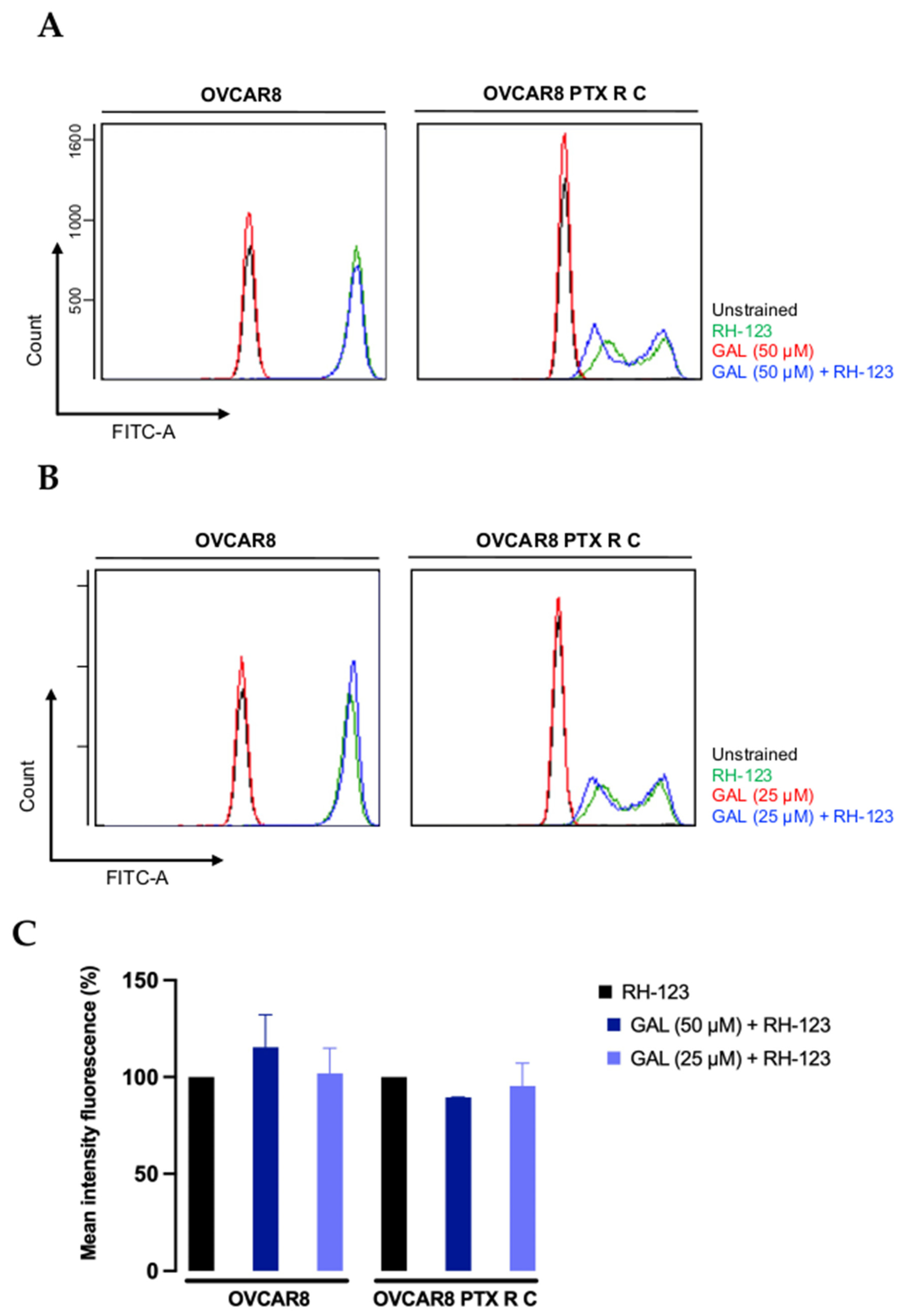

3.5. Galanthamine Does Not Inhibit the P-Glycoprotein Efflux Pump Function

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EDTA | Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GAL | Galanthamine |

| HGSC | High-grade serous carcinoma |

| HSA | Highest single agent |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| MIF | Mean intensity fluorescence |

| MSLN | Mesothelin |

| OC | Ovarian Cancer |

| PB | Presto Blue |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| P-gp | P-glycoprotein |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| RH-123 | rhodamine-123 |

| ZIP | zero interaction potency |

References

- World Cancer Research Fund International. Ovarian Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/cancer-trends/ovarian-cancer-statistics/ (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- De Leo, A.; Santini, D.; Ceccarelli, C.; Santandrea, G.; Palicelli, A.; Acquaviva, G.; Chiarucci, F.; Rosini, F.; Ravegnini, G.; Pession, A.; et al. What Is New on Ovarian Carcinoma: Integrated Morphologic and Molecular Analysis Following the New 2020 World Health Organization Classification of Female Genital Tumors. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, J.; Mutch, D.G. Pathology of cancers of the female genital tract including molecular pathology. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 143, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulonis, U.A.; Sood, A.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Howitt, B.E.; Sehouli, J.; Karlan, B.Y. Ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, T.; Mullangi, S.; Lekkala, M.R. Epithelial Ovarian Cancer; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567760/ (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Kim, S.; Kim, B.; Song, Y.S. Ascites modulates cancer cell behavior, contributing to tumor heterogeneity in ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 1173–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, S.; Coward, J.I.; Bast, R.C., Jr.; Berchuck, A.; Berek, J.S.; Brenton, J.D.; Coukos, G.; Crum, C.C.; Drapkin, R.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; et al. Rethinking ovarian cancer: Recommendations for improving outcomes. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gornstein, E.; Schwarz, T.L. The paradox of paclitaxel neurotoxicity: Mechanisms and unanswered questions. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamazawa, S.; Kigawa, J.; Kanamori, Y.; Itamochi, H.; Sato, S.; Iba, T.; Terakawa, N. Multidrug Resistance Gene-1 Is a Useful Predictor of Paclitaxel-Based Chemotherapy for Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2002, 86, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Anand, U.; Pandey, S.K.; Ashby, C.R.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Chen, Z.-S.; Dey, A. Therapeutic strategies to overcome taxane resistance in cancer. Drug Resist. Updates 2021, 55, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Swain, S.M. Peripheral Neuropathy Induced by Microtubule-Stabilizing Agents. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 1633–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Dong, W.; Li, M.; Shen, Y. Mitochondria P-glycoprotein confers paclitaxel resistance on ovarian cancer cells. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 3881–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Zhang, W.; Gupta, P.; Lei, Z.-N.; Wang, J.-Q.; Cai, C.-Y.; De Vera, A.A.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.-S.; Yang, D.-H. Tetrandrine Interaction with ABCB1 Reverses Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Cells Through Competition with Anti-Cancer Drugs Followed by Downregulation of ABCB1 Expression. Molecules 2019, 24, 4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasseur, K.; Gévry, N.; Asselin, E. Chemoresistance and targeted therapies in ovarian and endometrial cancers. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 4008–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freimund, A.E.; Beach, J.A.; Christie, E.L.; Bowtell, D.D.L. Mechanisms of Drug Resistance in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 32, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampan, N.C.; Madondo, M.T.; McNally, O.M.; Quinn, M.; Plebanski, M. Paclitaxel and Its Evolving Role in the Management of Ovarian Cancer. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 413076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Kaye, S.B. Ovarian cancer: Strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghray, D.; Zhang, Q. Inhibit or Evade Multidrug Resistance P-Glycoprotein in Cancer Treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5108–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robey, R.W.; Pluchino, K.M.; Hall, M.D.; Fojo, A.T.; Bates, S.E.; Gottesman, M.M. Revisiting the role of ABC transporters in multidrug-resistant cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaghan, R.; Luk, F.; Bebawy, M. Inhibition of the Multidrug Resistance P-Glycoprotein: Time for a Change of Strategy? Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lv, X.; Gao, M.; Gong, X.; Yao, Q.; Liu, Y. Nanoparticle-Based Combination Therapy for Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 1965–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, A.H.; Rønsted, N.; Güler, S.; Jäger, A.K.; Sendra, J.R.; Brodin, B. In-Vitro evaluation of the P-glycoprotein interactions of a series of potentially CNS-active Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 1667–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namanja, H.A.; Emmert, D.; Pires, M.M.; Hrycyna, C.A.; Chmielewski, J. Inhibition of human P-glycoprotein transport and substrate binding using a galantamine dimer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 388, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezoulin, M.J.M.; Ombetta, J.E.; Dutertre-Catella, H.; Warnet, J.M.; Massicot, F. Antioxidative properties of galantamine on neuronal damage induced by hydrogen peroxide in SK-N-SH cells. Neurotoxicology 2008, 29, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilder, R.J.; Hall, L.; Monks, A.; Handel, L.M.; Fornace, A.J.; Ozols, R.F.; Fojo, A.T.; Hamilton, T.C. Metallothionein gene expression and resistance to cisplatin in human ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 1990, 45, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, M.; Silva, P.M.A.; Coelho, R.; Pinto, C.; Resende, A.; Bousbaa, H.; Almeida, G.M.; Ricardo, S. Generation of Two Paclitaxel-Resistant High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cell Lines with Increased Expression of P-Glycoprotein. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 752127, Erratum in Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 853608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, S.-W.; Mok, S.C.; Fey, E.G.; Fletcher, J.A.; Wan, T.S.; Chew, E.-C.; Muto, M.G.; Knapp, R.C.; Berkowitz, R.S. Characterization of human ovarian surface epithelial cells immortalized by human papilloma viral oncogenes (HPV-E6E7 ORFs). Exp. Cell Res. 1995, 218, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.; Duarte, D.; Vale, N.; Ricardo, S. Pitavastatin and Ivermectin Enhance the Efficacy of Paclitaxel in Chemoresistant High-Grade Serous Carcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Fu, J.-N.; Chou, T.-C. Synergistic combination of microtubule targeting anticancer fludelone with cytoprotective panaxytriol derived from panax ginseng against MX-1 cells in vitro: Experimental design and data analysis using the combination index method. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2016, 6, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, W.; Aldahdooh, J.; Malyutina, A.; Shadbahr, T.; Tanoli, Z.; Pessia, A.; Tang, J. SynergyFinder Plus: Toward Better Interpretation and Annotation of Drug Combination Screening Datasets. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 20, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, D.; Cardoso, A.; Vale, N. Synergistic growth inhibition of HT-29 colon and MCF-7 breast cancer cells with simultaneous and sequential combinations of antineoplastics and CNS drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Kreitman, R.J.; Pastan, I.; Willingham, M.C. Localization of Mesothelin in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2005, 13, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.T.; Jiang, G.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, J.N. Ki67 is a promising molecular target in the diagnosis of cancer (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 1566–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenev, T.; Marani, M.; McNeish, I.; Lemoine, N.R. Pro-caspase-3 overexpression sensitises ovarian cancer cells to proteasome inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 2001, 8, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armando, R.G.; Gómez, D.L.M.; Gomez, D.E. New drugs are not enough-drug repositioning in oncology: An update. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 56, 651–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broekman, K.E.; Hof, M.A.J.; Touw, D.J.; Gietema, J.A.; Nijman, H.W.; Lefrandt, J.D.; Reyners, A.K.L.; Jalving, M. Phase I study of metformin in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Investig. New Drugs 2020, 38, 1454–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micha, J.P.; Rettenmaier, M.A.; Bohart, R.D.; Goldstein, B.H. A phase II, open-label, non-randomized, prospective study assessing paclitaxel, carboplatin and metformin in the treatment of advanced stage ovarian carcinoma. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 34, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernicova, I.; Korbonits, M. Metformin—Mode of action and clinical implications for diabetes and cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couttenier, A.; Lacroix, O.; Vaes, E.; Cardwell, C.R.; De Schutter, H.; Robert, A. Statin use is associated with improved survival in ovarian cancer: A retrospective population-based study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wolf, E.; Abdullah, M.I.; Jones, S.M.; Menezes, K.; Moss, D.M.; Drijfhout, F.P.; Hart, S.R.; Hoskins, C.; Stronach, E.A.; Richardson, A. Dietary geranylgeraniol can limit the activity of pitavastatin as a potential treatment for drug-resistant ovarian cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, J.E.; Guo, H.; Sheng, X.; Han, X.; Schointuch, M.N.; Gilliam, T.P.; Gehrig, P.A.; Zhou, C.; Bae-Jump, V.L. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, simvastatin, exhibits anti-metastatic and anti-tumorigenic effects in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgopapadakou, N.H.; Walsh, T.J. Antifungal agents: Chemotherapeutic targets and immunologic strategies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takara, K.; Tanigawara, Y.; Komada, F.; Nishiguchi, K.; Sakaeda, T.; Okumura, K. Cellular Pharmacokinetic Aspects of Reversal Effect of Itraconazole on P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Resistance of Anticancer Drugs. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 22, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.-J.; Lew, K.; Casciano, C.N.; Clement, R.P.; Johnson, W.W. Interaction of Common Azole Antifungals with P Glycoprotein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.; Bartosch, C.; Abreu, M.H.; Richardson, A.; Almeida, R.; Ricardo, S. Deciphering the Molecular Mechanisms behind Drug Resistance in Ovarian Cancer to Unlock Efficient Treatment Options. Cells 2024, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihara, T.; Sawada, H.; Nakamizo, T.; Kanki, R.; Yamashita, H.; Maelicke, A.; Shimohama, S. Galantamine modulates nicotinic receptor and blocks Aβ-enhanced glutamate toxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 325, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, K.; Stavrakov, G.; Philipova, I.; Atanasova, M.; Petrova, S.; Doumanov, J.; Doytchinova, I. A Galantamine–Curcumin Hybrid Decreases the Cytotoxicity of Amyloid-Beta Peptide on SH-SY5Y Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, E.; Alés, E.; Gabilan, N.H.; Cano-Abad, M.F.; Villarroya, M.; García, A.G.; López, M.G. Galantamine prevents apoptosis induced by β-amyloid and thapsigargin: Involvement of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuropharmacology 2004, 46, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavian, S.M.; Parsaee, H.; Mousavi, S.H.; Tayarani-Najaran, Z.; Ghorbani, A.; Sadeghnia, H.R. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors Promote Angiogenesis in Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane and Inhibit Apoptosis of Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013, 2013, 121068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obreshkova, D.; Atanasov, P.; Chaneva, M.; Ivanova, S.; Balkanski, S.; Peikova, L. Cytotoxic activity of Galantamine hydrobromide against HeLa cell line. Pharmacia 2023, 70, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.; Egea, J.; García, A.G.; López, M.G. Synergistic neuroprotective effect of combined low concentrations of galantamine and melatonin against oxidative stress in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J. Pineal Res. 2010, 49, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsikhan, R.S.; Aldubayan, M.A.; Almami, I.S.; Alhowail, A.H. Protective Effect of Galantamine against Doxorubicin-Induced Neurotoxicity. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Bharadwaj, U.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, S.; Mu, H.; Fisher, W.E.; Brunicardi, F.C.; Chen, C.; Yao, Q. Mesothelin is a malignant factor and therapeutic vaccine target for pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista-Pinto, C.; Resende, A.D.; Andrade, R.; Garcez, F.; Ferreira, V.; Lobo, C.; Monteiro, P.; Abreu, M.H.; Bartosch, C.; Ricardo, S. Tumor aggregates from ovarian cancer patients ascitic fluid present low caspase-3 expression. Sci. Lett. 2023, 1 (Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.; Nunes, D.; Ricardo, S. Cell Microarray: An Approach to Evaluate Drug-Induced Alterations in Protein Expression. In Advancements in Cancer Research; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2023; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, J.P.; Kunta, J.R. Development, validation and utility of an in vitro technique for assessment of potential clinical drug–drug interactions involving P-glycoprotein. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 27, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference Models | Cell Lines | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVCAR8 | OVCAR8 PTX R C | HOSE6.3 | ||

| Zero Interaction Potency | Synergy Score | −1.881 | −0.760 | −3.248 |

| Most Synergic Area Score | 8.739 | 14.173 | 1.053 | |

| Interaction | Additive | Additive | Additive | |

| Loewe | Synergy Score | 1.275 | 3.739 | 1.228 |

| Most Synergic Area Score | 14.587 | 21.429 | 6.130 | |

| Interaction | Additive | Additive | Additive | |

| Bliss Independence | Synergy Score | −1.868 | −0.171 | −3.491 |

| Most Synergic Area Score | 10.303 | 17.833 | 4.507 | |

| Interaction | Additive | Additive | Additive | |

| Highest Single Agent | Synergy Score | 1.290 | 3.601 | 1.784 |

| Most Synergic Area Score | 13.919 | 22.486 | 6.900 | |

| Interaction | Additive | Additive | Additive | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fonseca, N.; Nunes, M.; Silva, P.M.A.; Bousbaa, H.; Ricardo, S. Galanthamine Fails to Reverse P-gp-Mediated Paclitaxel Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122852

Fonseca N, Nunes M, Silva PMA, Bousbaa H, Ricardo S. Galanthamine Fails to Reverse P-gp-Mediated Paclitaxel Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122852

Chicago/Turabian StyleFonseca, Nélia, Mariana Nunes, Patrícia M. A. Silva, Hassan Bousbaa, and Sara Ricardo. 2025. "Galanthamine Fails to Reverse P-gp-Mediated Paclitaxel Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122852

APA StyleFonseca, N., Nunes, M., Silva, P. M. A., Bousbaa, H., & Ricardo, S. (2025). Galanthamine Fails to Reverse P-gp-Mediated Paclitaxel Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2852. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122852