Effect of Aging on the Morphofunctional Characteristics of Oral Cavity Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Search

2.2. Eligible Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

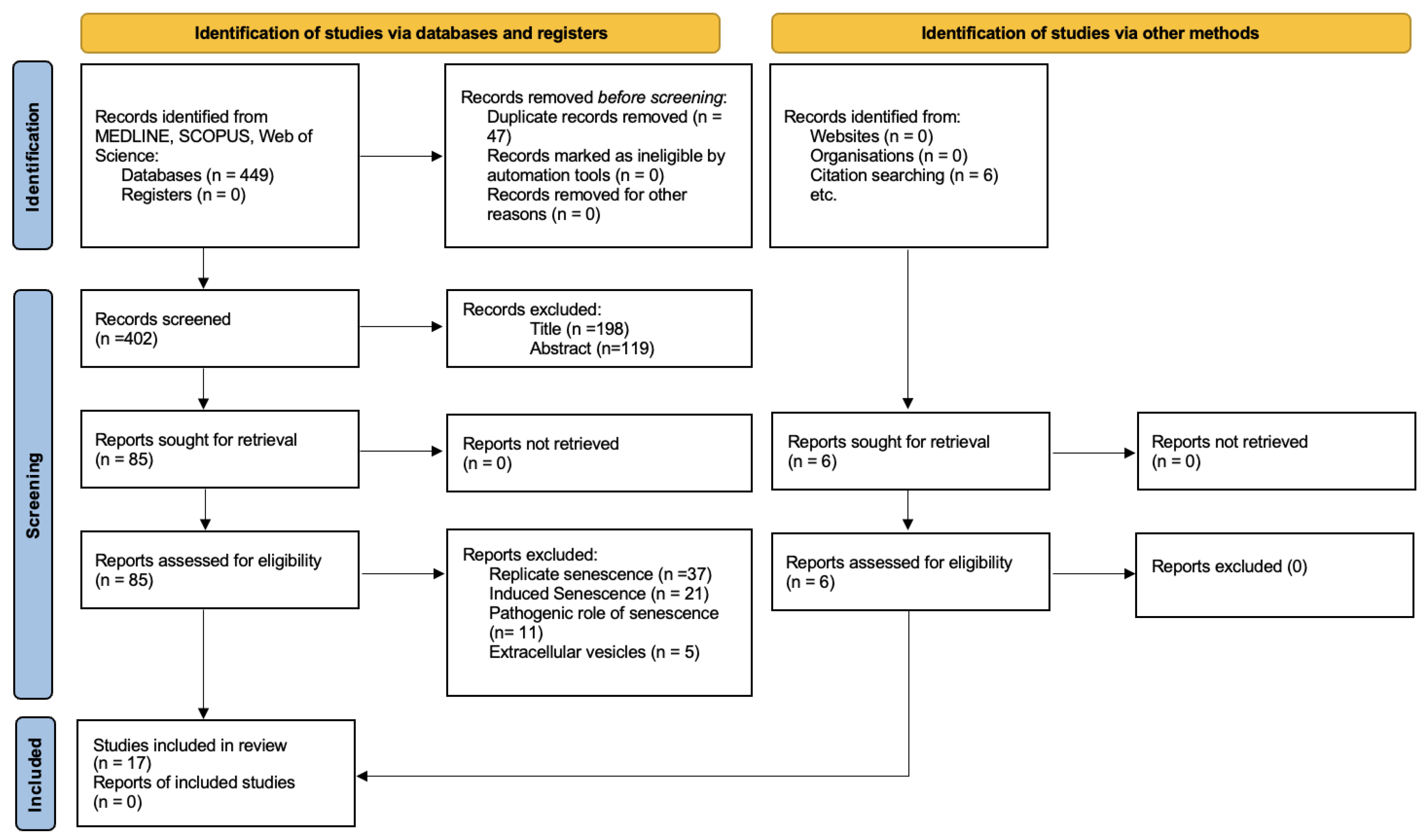

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Selected Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Cellular Senescence

4.2. Secretome

4.3. Tissue-of-Origin Effect on Senescence

4.4. Donor Age

4.5. Cell Morphology

4.6. MSC Markers

4.7. Molecular and Functional Markers of Senescence

4.8. Proliferation and Viability

4.9. Immunomodulation

4.10. Multilineage Differentiation In Vitro

4.10.1. Osteogenic Differentiation

4.10.2. Adipogenic Differentiation

4.10.3. Chondrogenic Differentiation

4.10.4. Neurogenic Differentiation

4.11. Experimental Medicine

4.12. Future Prospects

4.13. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DPSCs | Dental pulp stem cells |

| SHEDS | Stem cells from exfoliated deciduous teeth |

| PDLSCs | Periodontal ligament stem cells |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stromal cell |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| α-MEM | Alpha minimum essential medium |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| CD | Cluster of differentiation |

| PDT | Population doubling time |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| HLA-DR | Human leukocyte antigen—DR isotype |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cell |

| SA-β-gal | Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| PC | Periosteal cells |

| ISCT | International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy |

| CAV-1 | Caveolin-1 |

References

- Lan, T.; Luo, M.; Wei, X. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Shi, S.; Liu, Y.; Uyanne, J.; Shi, Y.; Shi, S.; Le, A.D. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from human gingiva are capable of immunemodulatory functions and ameliorate inflammation-related tissue destruction in experimental colitis. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 7787–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedenstein, A.J.; Petrakova, K.V.; Kurolesova, A.I.; Frolova, G.P. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation 1968, 6, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfia, G.; Navone, S.E.; Di Vito, C.; Ughi, N.; Tabano, S.; Miozzo, M.; Tremolada, C.; Bolla, G.; Crotti, C.; Ingegnoli, F.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: Potential for therapy and treatment of chronic non-healing skin wounds. Organogenesis 2015, 11, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Martínez, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M.; Santiago-Osorio, E. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Periodontal Tissue Regeneration in Elderly Patients. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 1351–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, A.R.; Carrión, F.S.; Chaparro, A.P. Mesenchymal stem cells from the oral cavity and their potential value in tissue engineering. Periodontology 2000 2015, 67, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonab, M.M.; Alimoghaddam, K.; Talebian, F.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Ghavamzadeh, A.; Nikbin, B. Aging of mesenchymal stem cell in vitro. BMC Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadpanah, R.; Kaushal, D.; Kriedt, C.; Tsien, F.; Patel, B.; Dufour, J.; Bunnell, B.A. Long-term in vitro expansion alters the biology of adult mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 4229–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushahary, D.; Spittler, A.; Kasper, C.; Weber, V.; Charwat, V. Isolation, cultivation, and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cytom. Part A J. Int. Soc. Anal. 2018, 93, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Apablaza, J.; Prieto, R.; Rojas, M.; Fuentes, R. Potential of Oral Cavity Stem Cells for Bone Regeneration: A Scoping Review. Cells 2023, 12, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yu, F.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Xu, G.T.; Liang, A.; Liu, S. Concise reviews: Characteristics and potential applications of human dental tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave, J.R.; Chandekar, S.S.; Behera, S.; Desai, K.U.; Salve, P.M.; Sapkal, N.B.; Mhaske, S.T.; Dewle, A.M.; Pokare, P.S.; Page, M. Human gingival mesenchymal stem cells retain their growth and immunomodulatory characteristics independent of donor age. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Yang, P.; Ge, S. Isolation and characterization of human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells using limiting dilution method. J. Dent. Sci. 2016, 11, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, M.S.; Emami, G.; Khodadadi, H.; Baban, B. Stem cells and tooth regeneration: Prospects for personalized dentistry. EPMA J. 2019, 10, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, G.B.; Srivastava, R.K.; Gupta, N.; Barhanpurkar, A.P.; Pote, S.T.; Jhaveri, H.M.; Mishra, G.C.; Wani, M.R. Human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells are superior to bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for cell therapy in regenerative medicine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, L.; Dang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, D.; Ma, J.; Yuan, J. Human Gingiva-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorate Streptozoticin-induced T1DM in mice via Suppression of T effector cells and Up-regulating Treg Subsets. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinkovic, M.; Tran, O.N.; Wang, H.; Abdul-Azees, P.; Dean, D.D.; Chen, X.D.; Yeh, C.K. Autologous mesenchymal stem cells offer a new paradigm for salivary gland regeneration. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Rocca, Y.; Diomede, F.; Konstantinidou, F.; Gatta, V.; Stuppia, L.; Benedetto, U.; Zimarino, M.; Lanuti, P.; Trubiani, O.; Pizzicannella, J. Autologous hGMSC-Derived iPS: A New Proposal for Tissue Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abo Qoura, L.; Churov, A.V.; Maltseva, O.N.; Arbatskiy, M.S.; Tkacheva, O.N. The aging interactome: From cellular dysregulation to therapeutic frontiers in age-related diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2026, 1872, 168060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.Y.G.; VanHeest, M.; Emmadi, S.; Abdul-Hafez, A.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Thiruvenkataramani, R.P.; Teleb, R.S.; Omar, H.; Kesaraju, T.; Mohamed, T.; et al. Role of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells (MSCs) and MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) in Prevention of Telomere Length Shortening, Cellular Senescence, and Accelerated Biological Aging. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylonas, A.; O’Loghlen, A. Cellular Senescence and Ageing: Mechanisms and Interventions. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 866718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azab, M.; Safi, M.; Idiiatullina, E.; Al-Shaebi, F.; Zaky, M.Y. Aging of mesenchymal stem cell: Machinery, markers, and strategies of fighting. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.K.; Ogando, C.R.; Wang See, C.; Chang, T.Y.; Barabino, G.A. Changes in phenotype and differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells aging in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.; Gil, J. Senescence and aging: Causes, consequences, and therapeutic avenues. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hong, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Mesenchymal stem cell senescence and rejuvenation: Current status and challenges. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zamudio, R.I.; Roux, P.F.; de Freitas, J.A.N.L.F.; Robinson, L.; Doré, G.; Sun, B.; Belenki, D.; Milanovic, M.; Herbig, U.; Schmitt, C.A.; et al. AP-1 imprints a reversible transcriptional programme of senescent cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, O.; Tanizawa, H.; Kim, K.D.; Kossenkov, A.; Nacarelli, T.; Tashiro, S.; Majumdar, S.; Showe, L.C.; Zhang, R.; Noma, K.I. Involvement of condensin in cellular senescence through gene regulation and compartmental reorganization. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ouchi, T.; Liu, H.; Qiao, X.; Wu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Li, L.; Li, B. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell Senescence: Hallmarks, Mechanisms, and Combating Strategies. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Shen, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D. The role of cellular senescence in metabolic diseases and the potential for senotherapeutic interventions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1276707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafián-Labora, J.A.; Morente-López, M.; Arufe, M.C. Effect of aging on behaviour of mesenchymal stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 2019, 11, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, B.; Genova, E.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Y.; Shi, X.; Isales, C.; Eroglu, A. Photobiomodulation has rejuvenating effects on aged bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariano, E.D.; Teixeira, M.J.; Marie, S.K.; Lepski, G. Adult stem cells in neural repair: Current options, limitations and perspectives. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lossdörfer, S.; Kraus, D.; Jäger, A. Aging affects the phenotypic characteristics of human periodontal ligament cells and the cellular response to hormonal stimulation in vitro. J. Periodontal Res. 2010, 45, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, E.; Ferroni, L.; Gardin, C.; Pinton, P.; Stellini, E.; Botticelli, D.; Sivolella, S.; Zavan, B. Donor age-related biological properties of human dental pulp stem cells change in nanostructured scaffolds. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; An, Y.; Gao, L.N.; Zhang, Y.J.; Jin, Y.; Chen, F.M. The effect of aging on the pluripotential capacity and regenerative potential of human periodontal ligament stem cells. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6974–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Xing, J.; Feng, G.; Sang, A.; Shen, B.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, S.; Tan, W.; Gu, Z.; et al. Age-dependent impaired neurogenic differentiation capacity of dental stem cell is associated with Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 33, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, M.; Steindorff, M.M.; Strempel, J.F.; Winkel, A.; Kühnel, M.P.; Stiesch, M. Differences of isolated dental stem cells dependent on donor age and consequences for autologous tooth replacement. Arch. Oral Biol. 2014, 59, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukua, N.; Chen, M.; Guarnieri, P.; Dahl, M.; Lim, M.L.; Yucel-Lindberg, T.; Sundström, E.; Adameyko, I.; Mao, J.J.; Fried, K. Molecular differences between stromal cell populations from deciduous and permanent human teeth. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ceccarelli, G.; Graziano, A.; Benedetti, L.; Imbriani, M.; Romano, F.; Ferrarotti, F.; Aimetti, M.; Cusella de Angelis, G.M. Osteogenic Potential of Human Oral-Periosteal Cells (PCs) Isolated from Different Oral Origin: An In Vitro Study. J. Cell Physiol. 2016, 231, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, C.T.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y.J.; Sun, G.L. Derivation and growth characteristics of dental pulp stem cells from patients of different ages. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5127–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.X.; Bi, C.S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Chen, F.M. Age-related decline in the matrix contents and functional properties of human periodontal ligament stem cell sheets. Acta Biomater. 2015, 22, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Q.; Liu, O.; Yan, F.; Lin, X.; Diao, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, L.; Wang, S.; Lu, Y.; Fan, Z. Analysis of Senescence-Related Differentiation Potentials and Gene Expression Profiles in Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Cells Tissues Organs 2017, 203, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Liu, N.; Gu, B.; Li, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T. Effects of Aging on the Proliferation and Differentiation Capacity of Human Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 2017, 32, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iezzi, I.; Cerqueni, G.; Licini, C.; Lucarini, G.; Mattioli Belmonte, M. Dental pulp stem cells senescence and regenerative potential relationship. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 7186–7197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, G.; Wei, F. The effect of aging on the biological and immunological characteristics of periodontal ligament stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.K.; Chen, C.B.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y.; Yao, X.; Huang, L.; Liang, J.J.; Cheung, H.S.; Pang, C.P.; Huang, Y. Attenuated regenerative properties in human periodontal ligament-derived stem cells of older donor ages with shorter telomere length and lower SSEA4 expression. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 381, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Kawase-Koga, Y.; Yamakawa, D.; Fujii, Y.; Chikazu, D. Bone Regeneration Potential of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Derived from Elderly Patients and Osteo-Induced by a Helioxanthin Derivative. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.L.; Huang, H.M.; Han, C.S.; Cui, S.J.; Zhou, Y.K.; Zhou, Y.H. Serine Metabolism Controls Dental Pulp Stem Cell Aging by Regulating the DNA Methylation of p16. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, O.; Chen, S.; Zhou, Y. Aging and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Therapeutic Opportunities and Challenges in the Older Group. Gerontology 2022, 68, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimri, G.P.; Lee, X.; Basile, G.; Acosta, M.; Scott, G.; Roskelley, C.; Medrano, E.E.; Linskens, M.; Rubelj, I.; Pereira-Smith, O. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 9363–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valieva, Y.; Ivanova, E.; Fayzullin, A.; Kurkov, A.; Igrunkova, A. Senescence-Associated β-Galactosidase Detection in Pathology. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Zamudio, R.I.; Dewald, H.K.; Vasilopoulos, T.; Gittens-Williams, L.; Fitzgerald-Bocarsly, P.; Herbig, U. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase reveals the abundance of senescent CD8+ T cells in aging humans. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernadotte, A.; Mikhelson, V.M.; Spivak, I.M. Markers of cellular senescence. Telomere shortening as a marker of cellular senescence. Aging 2016, 8, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, J.K.; Lis-Nawara, A.; Grelewski, P.G. Dental Pulp Stem Cell-Derived Secretome and Its Regenerative Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiliana, A.; Dewi, N.M.; Wijaya, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategy in Regenerative Medicine. Indones. Biomed. J. 2019, 11, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, A.; García-Sánchez, D.; Dotta, M.; Rodríguez-Rey, J.C.; Pérez-Campo, F.M. Mesenchymal stem cells secretome: The cornerstone of cell-free regenerative medicine. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 1529–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, N.; Amin, L.E.; Zaher, A.R.; Scheven, B.A.; Grawish, M.E. Dental Pulp Stem Cells: Novel Cell-Based and Cell-Free Therapy for Peripheral Nerve Repair. World J. Stomatol. 2019, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volonte, D.; Galbiati, F. Caveolin-1, a master regulator of cellular senescence. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.M.; Kwon, O.; Kwon, K.S.; Cho, Y.S.; Rhee, S.K.; Min, J.K.; Oh, D.B. Evidences for correlation between the reduced VCAM-1 expression and hyaluronan synthesis during cellular senescence of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 404, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961, 25, 585–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudlova, N.; De Sanctis, J.B.; Hajduch, M. Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile, M.; Eiro, N.; Costa, L.A.; Martín, A.; Vizoso, F.J. Aging and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Basic Concepts, Challenges and Strategies. Biology 2022, 11, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, T.J.; Marinkovic, M.; Tran, O.N.; Gonzalez, A.O.; Marshall, A.; Dean, D.D.; Chen, X.D. Restoring the quantity and quality of elderly human mesenchymal stem cells for autologous cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Scholtemeijer, M.; Shah, K. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Immunomodulation: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Chiu, S.M.; Motan, D.A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, L.; Ji, H.L.; Tse, H.F.; Fu, Q.L.; Lian, Q. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: Current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahangar, P.; Mills, S.J.; Smith, L.E.; Gronthos, S.; Cowin, A.J. Human gingival fibroblast secretome accelerates wound healing through anti-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic mechanisms. npj Regen. Med. 2020, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Kohan, E.; Bradley, J.; Hedrick, M.; Benhaim, P.; Zuk, P. The effect of age on osteogenic, adipogenic and proliferative potential of female adipose-derived stem cells. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2009, 3, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhery, M.S.; Badowski, M.; Muise, A.; Pierce, J.; Harris, D.T. Donor age negatively impacts adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell expansion and differentiation. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, N.; Boyette, L.B.; Tuan, R.S. Characterization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in aging. Bone 2015, 70, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.M.; Dixon, K.; Beck, S.; Fabian, D.; Feldman, A.; Barry, F. Reduced chondrogenic and adipogenic activity of mesenchymal stem cells from patients with advanced osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 46, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruminis-Kaszkiel, E.; Osowski, A.; Bejer-Oleńska, E.; Dziekoński, M.; Wojtkiewicz, J. Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Wharton’s Jelly Towards Neural Stem Cells Using a Feasible and Repeatable Protocol. Cells 2020, 9, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Monjaraz, B.; Santiago-Osorio, E.; Ledesma-Martínez, E.; Aguiñiga-Sánchez, I.; Sosa-Hernández, N.A.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Dental Pulp Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Treatment for Periodontal Disease in Older Adults. Stem Cells Int. 2020, 2020, 8890873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanovski, S.; Han, P.; Peters, O.A.; Sanz, M.; Bartold, P.M. The Therapeutic Use of Dental Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Human Clinical Trials. J. Dent. Res. 2024, 103, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggi, C.; Berardi, A.C. Mesenchymal stem cells, aging and regenerative medicine. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012, 2, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meshram, M.; Anchlia, S.; Shah, H.; Vyas, S.; Dhuvad, J.; Sagarka, L. Buccal Fat Pad-Derived Stem Cells for Repair of Maxillofacial Bony Defects. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2019, 18, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scoping review title | The Effect of Aging throughout the life cycle on the Morphofunctional Characteristics of Oral Cavity Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Scoping Review |

| Review objective | To analyze the effect of age-related senescence on the morphofunctional characteristics of oral cavity MSCs. |

| Review question | What morphofunctional characteristics of oral cavity MSCs are altered by age-related senescence? |

| PICOR | P (Population): Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) derived from the oral cavity I (Intervention/Issue): age-related senescence C (Comparison): MSCs obtained from young individuals O (Outcome): Morphological and functional changes R (Research design): In vitro studies |

| Article | Country | Tissue of Origin | Cells | Study Groups | Cell Culture and Maintenance Methodology | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | Cell Maintenance | Experimentation Passages | |||||

| Lossdörfer, S., 2010 [35] | Germany | Premolars | PDLSCs | Group 1: 12–14 years Group 2: 20–40 years Group 3: 60–75 years | Human periodontal ligament cells were scraped from the middle third of the roots. | The tissue was maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 0.5% antibiotics (5000 U/mL penicillin and 5000 U/mL streptomycin) at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 100% humidity and 5% CO2 in air. | P5 |

| Bressan, E., 2012 [36] | Italy | Molars | DPSCs | Group: 16–25 years Group: 26–35 years Group: 36–45 years Group: 46–55 years Group: 56–65 years Group: >66 years | The pulp was removed and immersed for 1 h at 37 °C in a digestive solution of 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, 0.6 mL of 500 mg/mL clarithromycin, 3 mg/mL collagen type I, and 4 mg/mL dispase in 4 mL of 1 M PBS. Once digested, the solution was filtered through 70 mm Falcon strainers. | Non-hematopoietic (NH) stem cell expansion medium | P2–P8 |

| Zhang, J., 2012 [37] | China | Impacted third molars | PDLSCs | Group A: 16–30 years Group B: 31–40 years Group C: 41–55 years Group D: 56–75 years | The teeth were rinsed, and the PDL was removed from the middle third of the root surface. The PDL was washed and then cut into 1 mm3 cubes. They were then digested with collagenase type I and dispase in α-MEM for 15 min at 37 °C with shaking. | Tissue explants were placed in culture dishes with Alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM), 10% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and ascorbic acid and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. | P3–P5 |

| Feng, X., 2013 [38] | China | Incisors Third molars | SHEDs DPSCs | Group A: 5–12 years Group B: 45–50 years | The pulp was washed three times with PBS. The pulp tissue was then cut into pieces and placed in a solution of 3.0 mg/mL collagenase type I and 4.0 mg/mL dispase. The tissue was digested at 37 °C for 1 h and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 8 min. Cell suspensions were seeded in 10 cm culture dishes. | The tissue was maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every 3 days. | P3–P5 |

| Kellner M, 2014 [39] | Germany | Third molars | DPSCs | Group A: >22 years Group B: <22 years | The pulp was digested in 4 mg/mL collagenase type I and 2 mg/mL dispase for 1 h at 37 °C. | The cell suspension was cultured in α-MEM plus 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. | P1–P4 |

| Kaukua N, 2015 [40] | Sweden | DPSCs SHEDs | Group A: 3–12 years Group B: 19–52 years | Pulp tissue was digested with 3 mg/mL collagenase I and 4 mg/mL dispase for one hour at 37 °C. Dissociated cells were passed through a 70 μm cell strainer. | The tissue was maintained in α-MEM, 10% FBS, and penicillin-streptomycin. | P1–P3 | |

| Ceccarelli G., 2015 [41] | Italy | Periosteum of the upper vestibule, lower vestibule, and hard palate | PCs | Group A: 20–30 years Group B: 40–50 years Group C: 50–60 years | Periosteum samples were digested in a solution of collagenase I (3 mg/mL) and dispase (4 mg/mL) for 1 h at 37 °C. The cells obtained from the digestion were filtered through a 70 μm strainer. | α-MEM medium supplemented with 20% FBS, 100 μM 2 p ascorbic acid, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 1000 mg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C at 5% of CO2. The medium was changed twice a week. | Not reported |

| Wu, W., 2015 [42] | China | Deciduous and permanent teeth | DPSCs SHEDs | Group A: 4 to 8 years Group B: 12 to 20 years old Group C: 30 to 50 years Group D: 55 to 67 years | The pulp was gently separated from the crown and root. It was rinsed with PBS, sectioned into 1 mm2 pieces, and implanted in culture dishes. | Culture medium supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 80% humidity. | Not reported |

| Wu, R.X., 2015 [43] | China | Third molars | PDLSCs | Group A: 18–30 years Group B: 31–45 years Group C: 46–62 years | The teeth were rinsed with PBS, and the PDL was scraped from the middle of the root of each tooth. The PDL was cut into small blocks and digested in 3 mg/mL of collagenase type I and 4 mg/mL of dispase for 1 h. The digestive solution was then discarded and maintained in complete culture medium. | The tissues were suspended in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.292 mg/mL glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The medium was changed every 3 days. | P1–P3 |

| Yi, Q., 2016 [44] | China | Healthy teeth | DPSCs | Young people: 12–25 years Older people: 60–70 years | Dental pulp was digested in a solution of 3 mg/mL collagenase type I and 4 mg/mL dispase for 40 min at 37 °C. Single cell suspensions were obtained by passing the cells through a 70 μm strainer. | DPSCs were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in α-MEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 2 μM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 U/mL streptomycin. The culture medium was changed every 3 days. | P3–P5 |

| Du, T., 2017 [45] | China | Premolar Third molars | PDLSCs | Group A: 18–20 years (average age 19 years) Group B: 30–35 years (average age 32.5 years) Group C: 45–50 years (average age 47.5 years) | The teeth were rinsed repeatedly with PBS. PDL was scraped from the mid-root using surgical blades. The PDL tissue was minced into 1 mm3 cubes and then digested with collagenase type I solution in an incubator for 15 min. After centrifugation of the tissues (800 rpm), the supernatant fraction was discarded, and the tissues were resuspended and transferred to a six-well culture dish. | The tissue was maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin and subsequently cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The culture medium was changed every 3–4 days. | P2–P3 |

| Iezzi, I., 2019 [46] | Italy | Third molars | DPSCs | Group A: 20–23 years (average age: 21 years) Group B: 42–45 years (average age: 43 years) Group C: 62–66 years (average age: 64 years) | Enzymatic isolation (3.0 mg/mL collagenase type I and 4.0 mg/mL dispase) for 1 h at 37 °C, then filtered through 70 μm cell strainers to obtain the DPSC suspension. | The tissue was maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. | Not reported |

| Li, X., 2020 [47] | China | Third molars | PDLSCs | Youth (YPDLSC): 19–20 years Adults (APDLSC): 35–50 years | The periodontal ligament was scraped from the middle third of the root surface and seeded in cell culture flasks. | The tissue was maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The medium was refreshed every 2 to 3 days. | P3–P4 |

| Ng, T.K., 2020 [48] | China | Permanent teeth | PDLSCs | Group A: ≤20 years Group B: 20–40 years Group C: >40 years | PDL was mechanically scraped from the root surface and minced, followed by digestion with 0.1% collagenase types I and III in DMEM/F12 medium containing 0.5% FBS and antibiotics for 4 to 6 h with agitation (100 rpm) at 37 °C. The cells were cultured after passing through a 40 μm cell strainer. | The tissue was maintained in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 1× penicillin-streptomycin. The culture medium was changed every 3 days. | P3–P5 |

| Sato, M., 2020 [49] | Japan | - | DPSCs | Young people: 16–18 years Senior citizens: 41–54 years | The dental pulp was minced into small pieces, followed by enzymatic digestion using 3 mg/mL type I collagenase for 45 min at 37 °C. Cells were obtained by passing the suspension through a 70 µm cell strainer. | The tissue was maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 15% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The isolated cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per 100 mm dish. | P3–P4 |

| Yang, R.L., 2021 [50] | China | Incisors and premolars | DPSCs SHEDs | Group A: 8 to 10 years (mean age 8.6 years) Group B: 18 to 21 years (mean age 19.4 years) Group C: 55 to 61 years (mean age 57.6 years) | DPSCs were isolated from healthy donors and cultured in complete medium. | The tissue was maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 15% FBS, 100 μg/mL glutamine, 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, under a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. | P5–P8 |

| Dave, J.R., 2022 [13] | India | Gingival tissue during the gingivectomy or the extraction procedure | GMSCs | Group A: 13 to 31 years; mean ± SD age, 23.29 ± 6.26 years (n = 14) Group B: 37 to 55 years; mean ± SD age, 45.69 ± 6.49 years (n = 13) Group C: 59 to 80 years; mean ± SD age, 65.36 ± 6.57 years (n = 14) | The biopsy (2 × 1 × 1 mm3) of attached gingiva was washed in PBS. After removing the epithelial layer, it was minced into small pieces and incubated in a medium containing 0.1% collagenase and 0.2% dispase for 15 min at 37 °C. The first cell fraction was discarded, and the tissue was subjected to enzymatic digestion again for 5, 10, and 15 min. The cells were then washed and resuspended in complete medium. | The tissue was maintained in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. | P3–P12 |

| Article | Cell Morphology | MSC Markers | Senescence | Colony Formation and Growth Kinetics | Proliferation | PCR | Migration | Immunomodulation | In Vitro Differentiation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lossdörfer, S., 2010 [35] | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | The transcript expression of the senescence-associated gene caveolin-1 increased markedly with age. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Significantly lower expression of osteoblastic marker genes in aged cultures. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated |

| Bressan, E., 2012 [36] | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Proliferative capacity decreased with increasing age. DPSCs from elderly donors show better proliferative capacity at early in vitro passages (up to passage 2). | Type II collagen was detected in the chondrogenic medium. In the osteogenic medium, collagen I, osteopontin, osteonectin, and osteocalcin were abundant. In the adipogenic medium, PPARγ, adiponectin, and GLUT4 were observed. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | The classical adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic media were highly effective in inducing specific differentiation toward the expected cell lineages. DPSCs tend to differentiate into neuronal and bone cells rather than endothelial cells. |

| Zhang, J., 2012 [37] | The colonies were adherent and maintained their spindle-shaped morphology. | Negative for CD31 and CD34, and positive for CD29, CD44, CD90, CD105, CD146, and STRO-1. Expression levels of CD146 and STRO-1 decreased with age. | Not evaluated | The number of colony-forming units decreased with age. | Population doubling time was less than 24 h in all groups, with no significant differences among the four groups. The donor’s age influenced the initial cell growth rate. | Not evaluated | The migratory activity of PDLSCs decreased with increasing donor age. | Not evaluated | PDLSCs from all groups exhibited osteogenic and adipogenic potential. The differentiation capacity significantly decreased with donor aging. |

| Feng, X., 2013 [38] | SHED revealed a typical fibroblast-like morphology. DPSCs revealed flat and enlarged cell shapes. | Positive for CD29 and CD105, but negative for CD31 and CD34 | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Expression levels of neuronal markers, such as βIII-tubulin, microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), and nestin, were lower in the DPSC group than the SHED group. |

| Kellner, M., 2014 [39] | Not evaluated | Positive for CD29, CD44, and CD166. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Cells from older patients exhibit slower growth, although the maximum division potential of DPSCs does not vary significantly with age. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | No discrepancy was detected in the differentiation potential between DPSCs isolated from young and old donors. |

| Kaukua, N., 2015 [40] | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Genes promoting cell proliferation, mitosis, and division were highly expressed in cells from deciduous tooth pulp compared to those from permanent teeth. | Genes involved in cell cycle division and mitosis were highly expressed in cells from deciduous teeth. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated |

| Ceccarelli, G., 2015 [41] | spindle morphology | Positive for CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD29, and negative for CD45 and CD34. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Population doubling time ranged between 61 and 65 h, regardless of age. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Regardless of age, in the absence of any osteogenic induction, they commit to the osteoblastic lineage after 45 days of culture. |

| Wu, W., 2015 [42] | Adherent cells resembling fibroblasts. | Positive expression of CD13, CD29, CD59, and CD146, and negative expression of CD19, CD24, and CD45. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | No differences in proliferation were observed between groups at 48 h. At 72 and 96 h, DPSCs from elderly donors showed a lower proliferation rate than the other groups. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | DPSCs from deciduous teeth of children and permanent teeth of adolescents were capable of differentiating into neuronal and osteogenic lineages. DPSCs from aged teeth were completely or partially deprived of differentiation capacity. |

| Wu, R.X., 2015 [43] | Typical spindle-shaped morphology; cells from donors in Groups B and C were larger. | Negative for CD31 and CD45, and positive for CD90. CD146 positivity in Groups B and C was lower than in Group A | A statistically significant increase in SA-β-gal staining was observed with increasing age. | The CFU-F from young donors was greater than that formed by cells from relatively older donors. | The upward trend of the cell growth curve for Groups B and C was much slower than that of Group A. | The relative mRNA expression of the transcription factors Nanog, Oct-4, and Sox-2 showed an age-related decrease. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | All three groups showed potential for osteogenic differentiation, but cells from Group A appeared to accumulate more calcium deposits. No significant differences were observed between the groups in adipogenic differentiation. |

| Yi, Q., 2016 [44] | Not evaluated | Both negative for cell surface markers CD34, CD45, and HLA-DR, and positive for CD90, CD105, and CD146 | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | DPSCs from young donors showed greater proliferation capacity and significantly shorter doubling times than those from old donors. | OPN and lipoprotein lipase expressions were higher in DPSCs from young donors after osteogenic and adipogenic induction, respectively, while other markers showed no significant differences between age groups. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | DPSCs Isolated from Old Donors Exhibited Impaired Osteogenic and Adipogenic Differentiation Potentials Mineralization was also significantly stronger in the DPSCs from young donors than in the DPSCs from old donors. |

| Du, T., 2017 [45] | Presented an elongated morphology, and they showed a fibroblast-like appearance. | Not evaluated | SA-β g expression increased with donor age. | The colony-forming capacity decreased significantly with increasing donor age. | The proliferative capacity of PDLSCs decreased with increasing donor age. | The expression of genes related to osteogenesis, including ALP, Col-2, and Runx-2, gradually decreased from Group A to Group C. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | All three groups showed significant osteogenic differentiation potential. However, Group A exhibited the greatest staining intensity and area, while cells from Group C showed the lowest intensity and the smallest staining area. |

| Iezzi, I., 2019 [46] | No morphological differences were detected between the groups. | Positive for CD73, CD90, and CD105, and negative for CD45, HLA-DR, and CD14. | An increase in granularity and expression of SA-β-Gal and p16^INK4a was observed in Group C. No changes in cell size were evident. Telomere length in Group A was greater than in Groups B and C. | Not evaluated | After passage 13, cells from Groups B and C began to decline, and by passage 17, the DPSCs from Group C had ceased proliferation. | qRT-PCR analysis revealed age-related changes in the expression of stemness genes. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Reduction in adipogenic and osteogenic potential in cells from Group C compared to Groups A and B. No changes were observed in chondrogenic potential. |

| Li, X., 2020 [47] | APDLSCs showed irregular morphology with bifurcated cell borders. YPDLSCs exhibited a spindle-shaped morphology, abundant cytoplasm, and clear cell edges. | CD105 was positive in both groups. STRO-1 and CD146 expression was much lower in APDLSCs compared to YPDLSCs. CD45 and CD31 were negative in both groups. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | A CCK-8 assay showed that the proliferative activity of APDLSCs was lower than that of YPDLSCs during 7 days of cell growth. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | APDLSCs and YPDLSCs suppress the proliferation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). However, APDLSCs exhibit a weaker immunosuppressive capacity than YPDLSCs. | The osteogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation potential of PDLSCs in the adult group is lower than that in the young group. |

| Ng, T.K., 2020 [48] | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | The telomere length of human PDLSCs from donors older than 40 years was significantly 2.63 times shorter than that of donors aged 20 years or younger. | Not evaluated | The proliferative potential of human PDLSCs decreased with increasing donor age. | Not evaluated | The migratory capacity of human PDLSCs was diminished in the donor age group over 40 years. | No significant differences were observed in the expression of IDO1, IDO2, HLA-E, HLA-G, IL1B, and IL10, while IL6 and IL8 were expressed at higher levels in the 20–40 and >40-year-old groups. | The mesodermal lineage differentiation capacity of human PDLSCs decreased with increasing age. The expression of SSEA4 in human PDLSCs also declined with age. However, high proliferation levels were detected at passage 2 (P2) up to 56 years of age. |

| Santo, M., 2020 [49] | Typical spindle-shaped morphology | Positive for CD29, CD44, CD73, CD81, CD90, and CD105, and negative for CD14 and CD34. | Telomere length, a known marker of cellular senescence, remained stable in young and old DPSCs from P1 to P3. | Not evaluated | DPSCs from older patients showed lower initial proliferation but reached levels similar to those of younger patients from passage 3 onwards, with no significant differences throughout the entire period. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | Not evaluated |

| Yang, R.L., 2021 [50] | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | The level of p16 in A-DPSCs was higher than that in Y-DPSCs and SHEDs. | Not evaluated | A-DPSCs showed a lower proliferation rate than SHED and Y-DPSCs, and the latter proliferated less than SHEDs. | With increasing age, there was a decrease in the expression of odontogenic/osteogenic differentiation genes and an increase in the expression of adipogenic differentiation genes. | Not evaluated | Not evaluated | The osteogenic differentiation capacity of DPSCs decreased in an age-dependent manner. The adipogenic differentiation capacity of A-DPSCs was slightly higher than that of SHED and Y-DPSCs, indicating that adipogenic activity increased with aging. |

| Dave, J.R., 2022 [13] | Morphology of fibroblasts adhering to plastic | Positive for CD44, CD90, CD73 and CD105, without any contamination of hematopoietic cells (CD34 and CD45) | Group C showed a significantly larger population of senescent cells. | They formed efficient colonies; those of group A were larger than those of group C. | GMSCs from groups A, B, and C showed similar PDT at passages 9 and 11; however, PDT of group C increased significantly at passage 13. | Not evaluated | GMSCs in Group B showed a significantly higher migration rate than Groups A and C. | Not evaluated | Group A showed early signs of adipogenic differentiation compared to groups B and C. There was a significant decrease in mineralization in the osteogenic cultures of groups B and C. No decrease in the neurogenic differentiation capacity of GMSCs was observed with donor age. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alarcón-Apablaza, J.; Salazar, L.A.; Loren, P.; Martínez-Cardozo, C.; Fuentes, R. Effect of Aging on the Morphofunctional Characteristics of Oral Cavity Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Scoping Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112776

Alarcón-Apablaza J, Salazar LA, Loren P, Martínez-Cardozo C, Fuentes R. Effect of Aging on the Morphofunctional Characteristics of Oral Cavity Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Scoping Review. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112776

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlarcón-Apablaza, Josefa, Luis A. Salazar, Pía Loren, Constanza Martínez-Cardozo, and Ramón Fuentes. 2025. "Effect of Aging on the Morphofunctional Characteristics of Oral Cavity Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Scoping Review" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112776

APA StyleAlarcón-Apablaza, J., Salazar, L. A., Loren, P., Martínez-Cardozo, C., & Fuentes, R. (2025). Effect of Aging on the Morphofunctional Characteristics of Oral Cavity Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Scoping Review. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2776. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112776