Expression of Dystroglycanopathy-Related Enzymes, POMGNT2 and POMGNT1, in the Mammalian Retina and 661W Cone-like Cell Line

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Expression of POMGNT2 in the Mammalian Retina and the 661W Photoreceptor Cell Line

3.2. Immunolocalization of POMGNT2 and POMGNT1 in the Monkey and Mouse Retinas

3.3. Immunolocalization of POMGNT2 and POMGNT1 in the 661W Photoreceptor Cell Line

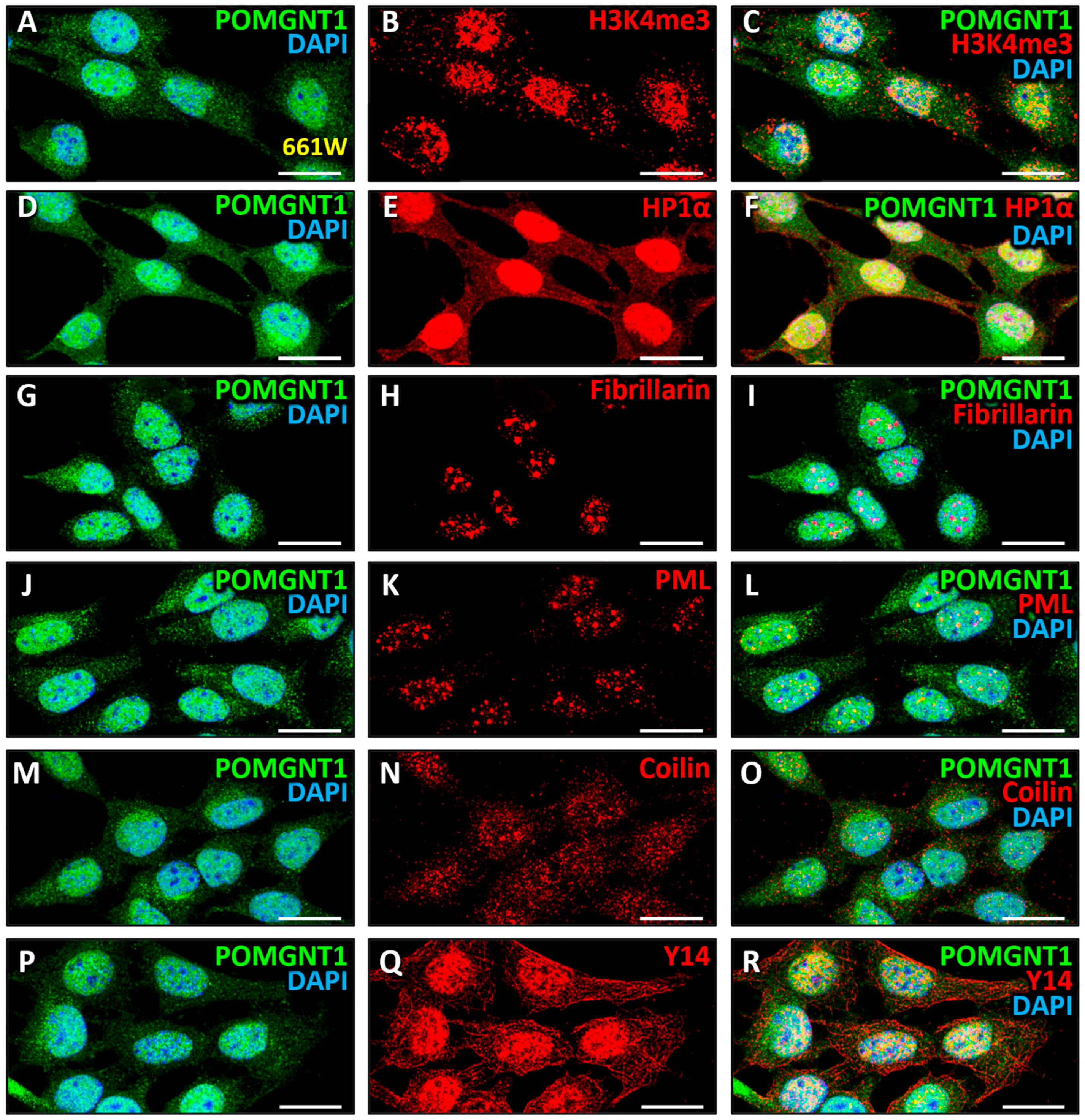

3.4. Intranuclear Distribution of POMGNT2 and POMGNT1 in the 661W Photoreceptor Cell Line

4. Discussion

4.1. Intracellular Distribution of Dystroglycanopathy-Associated Proteins in Mammalian Retinal Cells

4.2. Immunolocalization of POMGNT2 in the Monkey and Mouse Neural Retinas, and in the 661W Photoreceptor Cell Line

4.3. Immunolocalization of POMGNT1 in the Monkey Neural Retina and 661W Photoreceptor Cell Line

4.4. Coimmunolabeling of POMGNT2 and POMGNT1 in the Monkey and Mouse Neural Retinas, and 661W Photoreceptor Cell Line

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DGPs | Dystroglycanopathies |

| DG | Dystroglycan |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| DGC | Dystrophin-glycoprotein complex |

| OPL | Outer plexiform layer |

| POMGNT2 | Protein O-linked-mannose β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 2 |

| POMGNT1 | Protein O-linked-mannose β-1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1 |

| KO | Knockout |

| PB | Sodium phosphate buffer |

| IB | Immunoblotting |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| ICC | Immunocytochemistry |

| PBX | Triton X-100 |

| DAPI | 4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| MCC | Manders colocalization coefficient |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| DPBS | Dulbecco’s PBS |

| IS | Inner segment |

| OS | Outer segment |

| INL | Inner nuclear layer |

| GCL | Ganglion cell layer |

| IPL | Inner plexiform layer |

| H3K4me3 | Histone H3 trimethylated at amino acid Lys-4 |

| PML | Promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies |

| snRNPs | Small nuclear ribonucleoproteins |

| FKTN | Fukutin |

| FKRP | Fukutin-related protein |

| aa | Amino acid |

References

- Muntoni, F.; Brockington, M.; Torelli, S.; Brown, S.C. Defective Glycosylation in Congenital Muscular Dystrophies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2004, 17, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, P.T. Congenital Muscular Dystrophies Involving the O-Mannose Pathway. Curr. Mol. Med. 2007, 7, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.E. Abnormal Glycosylation of Dystroglycan in Human Genetic Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1792, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muntoni, F.; Torelli, S.; Wells, D.J.; Brown, S.C. Muscular Dystrophies Due to Glycosylation Defects: Diagnosis and Therapeutic Strategies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011, 24, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, C.M.; Hempel, S.J.; Stalnaker, S.H.; Stuart, R.; Wells, L. O-Mannosylation and Human Disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 2849–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jahncke, J.N.; Wright, K.M. The Many Roles of Dystroglycan in Nervous System Development and Function: Dystroglycan and Neural Circuit Development. Dev. Dyn. 2023, 252, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntoni, F.; Voit, T. The Congenital Muscular Dystrophies in 2004: A Century of Exciting Progress. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2004, 14, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schessl, J.; Zou, Y.; Bönnemann, C.G. Congenital Muscular Dystrophies and the Extracellular Matrix. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2006, 13, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, U. Congenital Muscular Dystrophy. Part I: A Review of Phenotypical and Diagnostic Aspects. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2009, 67, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, C.; Foley, A.R.; Clement, E.; Muntoni, F. Dystroglycanopathies: Coming Into Focus. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011, 21, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercuri, E.; Muntoni, F. The Ever-Expanding Spectrum of Congenital Muscular Dystrophies. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalheiser, N.R.; Schwartz, N.B. Cranin: A Laminin Binding Protein of Cell Membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 6457–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya, O.; Ervasti, J.M.; Leveille, C.J.; Slaughter, C.A.; Sernett, S.W.; Campbell, K.P. Primary Structure of Dystrophin-Associated Glycoproteins Linking Dystrophin to the Extracellular Matrix. Nature 1992, 355, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya, O.; Milatovich, A.; Ozcelik, T.; Yang, B.; Koepnick, K.; Francke, U.; Campbell, K.P. Human Dystroglycan: Skeletal Muscle cDNA, Genomic Structure, Origin of Tissue Specific Isoforms and Chromosomal Localization. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993, 2, 1651–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbeej, M. Laminins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 339, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbeej, M.; Larsson, E.; Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya, O.; Roberds, S.L.; Campbell, K.P.; Ekblom, P. Non-Muscle α-Dystroglycan is Involved in Epithelial Development. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 130, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durbeej, M.; Henry, M.D.; Ferletta, M.; Campbell, K.P.; Ekblom, P. Distribution of Dystroglycan in Normal Adult Mouse Tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1998, 46, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbeej, M.; Campbell, K.P. Biochemical Characterization of the Epithelial Dystroglycan Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 26609–26616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esser, A.K.; Cohen, M.B.; Henry, M.D. Dystroglycan Is Not Required for Maintenance of the Luminal Epithelial Basement Membrane or Cell Polarity in the Mouse Prostate. Prostate 2010, 70, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, K.H.; Crosbie, R.H.; Venzke, D.P.; Campbell, K.P. Biosynthesis of Dystroglycan: Processing of a Precursor Propeptide. FEBS Lett. 2000, 468, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhavan, A.; Crivelli, S.N.; Singh, M.; Lingappa, V.R.; Muschler, J.L. SEA Domain Proteolysis Determines the Functional Composition of Dystroglycan. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppizzi, M.L.; Akhavan, A.; Singh, M.; Fata, J.E.; Muschler, J.L. Nuclear Translocation of β-Dystroglycan Reveals a Distinctive Trafficking Pattern of Autoproteolyzed Mucins. Traffic 2008, 9, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ervasti, J.M.; Campbell, K.P. Membrane Organization of the Dystrophin-Glycoprotein Complex. Cell 1991, 66, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, A.; Schulthess, T.; Gesemann, M.; Engel, J. Electron Microscopic Evidence for a Mucin-Like Region in Chick Muscle α-Dystroglycan. FEBS Lett. 1995, 368, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, A.; Schulthess, T.; Gesemann, M.; Engel, J. The N-Terminal Region of α-Dystroglycan Is an Autonomous Globular Domain. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 246, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winder, S.J. The Complexities of Dystroglycan. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001, 26, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barresi, R.; Campbell, K.P. Dystroglycan: From Biosynthesis to Pathogenesis of Human Disease. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samwald, M. Review: Dystroglycan in the Nervous System. Nat. Preced. 2007, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Omori, Y.; Katoh, K.; Kondo, M.; Kanagawa, M.; Miyata, K.; Funabiki, K.; Koyasu, T.; Kajimura, N.; Miyoshi, T.; et al. Pikachurin, a Dystroglycan Ligand, Is Essential for Photoreceptor Ribbon Synapse Formation. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickolls, A.R.; Bönnemann, C.G. The Roles of Dystroglycan in the Nervous System: Insights From Animal Models of Muscular Dystrophy. Dis. Models Mech. 2018, 11, dmm035931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Poy, F.; Zhang, R.; Joachimiak, A.; Sudol, M.; Eck, M.J. Structure of a WW Domain Containing Fragment of Dystrophin in Complex With β-Dystroglycan. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000, 7, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzi, M.; Morlacchi, S.; Bigotti, M.G.; Sciandra, F.; Brancaccio, A. Functional Diversity of Dystroglycan. Matrix Biol. 2009, 28, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T. Glycobiology of α-Dystroglycan and Muscular Dystrophy. J. Biochem. 2015, 157, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, E.; Lommel, M.; Moro, M.; Crosti, M.; Lavazza, C.; Parazzi, V.; Saredi, S.; Strahl, S.; Lazzari, L. Protein O-Mannosylation Is Crucial for Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Fate. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, T. Mammalian O-Mannosyl Glycans: Biochemistry and Glycopathology. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2019, 95, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hino, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Shibata, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Saito, K.; Osawa, M. Clinicopathological Study on Eyes From Cases of Fukuyama Type Congenital Muscular Dystrophy. Brain Dev. 2001, 23, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kameya, S.; Cox, G.A.; Hsu, J.; Hicks, W.; Maddatu, T.P.; Smith, R.S.; Naggert, J.K.; Peachey, N.S.; Nishina, P.M. Ocular Abnormalities in Largemyd and Largevls Mice, Spontaneous Models for Muscle, Eye, and Brain Diseases. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2005, 30, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Candiello, J.; Zhang, P.; Ball, S.L.; Cameron, D.A.; Halfter, W. Retinal Ectopias and Mechanically Weakened Basement Membrane in a Mouse Model of Muscle-Eye-Brain (MEB) Disease Congenital Muscular Dystrophy. Mol. Vis. 2010, 16, 1415–1428. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida-Moriguchi, T.; Willer, T.; Anderson, M.E.; Venzke, D.; Whyte, T.; Muntoni, F.; Lee, H.; Nelson, S.F.; Yu, L.; Campbell, K.P.; et al. SGK196 Is a Glycosylation-Specific O-Mannose Kinase Required for Dystroglycan Function. Science 2013, 341, 896–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida-Moriguchi, T.; Campbell, K.P. Matriglycan: A Novel Polysaccharide That Links Dystroglycan to the Basement Membrane. Glycobiology 2015, 25, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmo, S.M.; Singh, D.; Patel, S.; Wang, S.; Edlin, M.; Boons, G.J.; Moremen, K.W.; Live, D.; Wells, L. Protein O-Linked Mannose β-1,4-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase 2 (POMGNT2) Is a Gatekeeper Enzyme for Functional Glycosylation of α-Dystroglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, M.C.; Tambunan, D.E.; Hill, R.S.; Yu, T.W.; Maynard, T.M.; Heinzen, E.L.; Shianna, K.V.; Stevens, C.R.; Partlow, J.N.; Barry, B.J.; et al. Exome Sequencing and Functional Validation in Zebrafish Identify GTDC2 Mutations as a Cause of Walker-Warburg Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Nakamura, N.; Nakayama, Y.; Kurosaka, A.; Manya, H.; Kanagawa, M.; Endo, T.; Furukawa, K.; Okajima, T. GTDC2 Modifies O-mannosylated α-Dystroglycan in the Endoplasmic Reticulum to Generate N-Acetyl Glucosamine Epitopes Reactive with CTD110.6 Antibody. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 440, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagi, H.; Nakagawa, N.; Saito, T.; Kiyonari, H.; Abe, T.; Toda, T.; Wu, S.; Khoo, K.; Oka, S.; Kato, K. AGO61-Dependent GlcNAc Modification Primes the Formation of Functional Glycans on α-Dystroglycan. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Y.; Dong, M.; Noguchi, S.; Ogawa, M.; Hayashi, Y.K.; Kuru, S.; Sugiyama, K.; Nagai, S.; Ozasa, S.; Nonaka, I.; et al. Milder Forms of Muscular Dystrophy Associated with POMGNT2 Mutations. Neurol. Genet. 2015, 1, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalnaker, S.H.; Aoki, K.; Lim, J.M.; Porterfield, M.; Liu, M.; Satz, J.S.; Buskirk, S.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Campbell, K.P.; et al. Glycomic Analyses of Mouse Models of Congenital Muscular Dystrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 21180–21190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praissman, J.L.; Wells, L. Mammalian O-Mannosylation Pathway: Glycan Structures, Enzymes, and Protein Substrates. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 3066–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida-Moriguchi, T.; Yu, L.; Stalnaker, S.; Sarah Davis, S.H.; Kunz, S.; Madson, M.; Oldstone, M.B.A.; Schachter, H.; Wells, L.; Campbell, K.P. O-Mannosyl Phosphorylation of Alpha-Dystroglycan Is Required for Laminin Binding. Science 2010, 327, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beedle, A.M.; Turner, A.J.; Saito, Y.; Lueck, J.D.; Foltz, S.J.; Fortunato, M.J.; Nienaber, P.M.; Campbell, K.P. Mouse fukutin Deletion Impairs Dystroglycan Processing and Recapitulates Muscular Dystrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 3330–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamori, K.I.; Yoshida-Moriguchi, T.; Hara, Y.; Anderson, M.E.; Yu, L.; Campbell, K.P. Dystroglycan Function Requires Xylosyl-and Glucuronyltransferase Activities of LARGE. Science 2012, 335, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuga, A.; Kanagawa, M.; Sudo, A.; Chan, Y.M.; Tajiri, M.; Manya, H.; Kikkawa, Y.; Nomizu, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Endo, T.; et al. Absence of Post-Phosphoryl Modification in Dystroglycanopathy Mouse Models and Wild-Type Tissues Expressing Non-Laminin Binding Form of α-Dystroglycan. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 9560–9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Kobayashi, M.; Hatakeyama, S.; Angata, K.; Gullberg, D.; Nakayama, J.; Fukuda, M.N.; Fukuda, M. Tumor Suppressor Function of Laminin-Binding α-Dystroglycan Requires a Distinct β3-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 12109–12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrán-Valero de Bernabé, D.; Inamori, K.I.; Yoshida-Moriguchi, T.; Weydert, C.J.; Harper, H.A.; Willer, T.; Henry, M.D.; Campbell, K.P. Loss of α-Dystroglycan Laminin Binding in Epithelium-Derived Cancers Is Caused by Silencing of LARGE. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 11279–11284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, S.; Hatakeyama, S.; Ohyama, C.; Fukuda, M. Two Opposing Roles of O-Glycans in Tumor Metastasis. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, A.K.; Miller, M.R.; Huang, Q.; Meier, M.M.; Beltrán-Valero de Bernabé, D.; Stipp, C.S.; Campbell, K.P.; Lynch, C.F.; Smith, B.J.; Cohen, M.B.; et al. Loss of LARGE2 Disrupts Functional Glycosylation of α-Dystroglycan in Prostate Cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 2132–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quereda, C.; Pastor, À.; Martín-Nieto, J. Involvement of Abnormal Dystroglycan Expression and Matriglycan Levels in Cancer Pathogenesis. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A.; Kobayashi, K.; Manya, H.; Taniguchi, K.; Kano, H.; Mizuno, M.; Inazu, T.; Mitsuhashi, H.; Takahashi, S.; Takeuchi, M.; et al. Muscular Dystrophy and Neuronal Migration Disorder Caused by Mutations in a Glycosyltransferase, POMGnT1. Dev. Cell 2001, 1, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satz, J.S.; Ostendorf, A.P.; Hou, S.; Turner, A.; Kusano, H.; Lee, J.C.; Turk, R.; Nguyen, H.; Ross-Barta, S.E.; Westra, S.; et al. Distinct Functions of Glial and Neuronal Dystroglycan in the Developing and Adult Mouse Brain. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 14560–14572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, K.M.; Lyon, K.A.; Leung, H.; Leahy, D.J.; Ma, L.; Ginty, D.D. Dystroglycan Organizes Axon Guidance Cue Localization and Axonal Pathfinding. Neuron 2012, 76, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Betel, D.; Schachter, H. Cloning and Expression of a Novel UDP-GlcNAc:α-D-Mannoside β1,2-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase Homologous to UDP-GlcNAc:α-3-D-mannoside β1,2-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I. Biochem. J. 2002, 361, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Tachikawa, M.; Manya, H.; Takeda, S.; Chiyonobu, T.; Fujikake, N.; Wang, F.; Nishimoto, A.; Morris, G.E.; et al. Molecular Interaction Between Fukutin and POMGnT1 in the Glycosylation Pathway of α-Dystroglycan. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 350, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, N.A.; Pu, H.X.; Goh, H.; Song, Z. Golgi Phosphoprotein 3 Mediates the Golgi Localization and Function of Protein O-Linked Mannose β-1,2-N-Acetlyglucosaminyltransferase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 14762–14770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, M.L.; Haro, C.; Ventero, M.P.; Campello, L.; Cruces, J.; Martín-Nieto, J. Expression Pattern in Retinal Photoreceptors of POMGnT1, a Protein Involved in Muscle-Eye-Brain Disease. Mol. Vis. 2016, 22, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, N.; Yagi, H.; Kato, K.; Takematsu, H.; Oka, S. Ectopic Clustering of Cajal-Retzius and Subplate Cells is an Initial Pathological Feature in Pomgnt2-Knockout Mice, a Model of Dystroglycanopathy. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ball, S.L.; Yang, Y.; Mei, P.; Zhang, L.; Shi, H.; Kaminski, H.J.; Lemmon, V.P.; Hu, H. A Genetic Model for Muscle–Eye–Brain Disease in Mice Lacking Protein O-Mannose 1,2-N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase (POMGnT1). Mech. Dev. 2006, 123, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Eade, A.; Xiong, Y.; Qi, Y. Breaches of the Pial Basement Membrane and Disappearance of the Glia Limitans During Development Underlie the Cortical Lamination Defect in the Mouse Model of Muscle-Eye-Brain Disease. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007, 502, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xiong, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, Y.; Hu, H. Ectopia of Meningeal Fibroblasts and Reactive Gliosis in the Cerebral Cortex of the Mouse Model of Muscle-Eye-Brain Disease. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007, 505, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y.; Masubuchi, N.; Miyamoto, K.; Wada, M.R.; Yuasa, S.; Saito, F.; Matsumura, K.; Kanesaki, H.; Kudo, A.; Manya, H.; et al. Reduced Proliferative Activity of Primary POMGnT1-Null Myoblasts In Vitro. Mech. Dev. 2009, 126, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagawa, M.; Omori, Y.; Sato, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y.; Takeda, S.; Endo, T.; Furukawa, T.; Toda, T. Post-Translational Maturation of Dystroglycan Is Necessary for Pikachurin Binding and Ribbon Synaptic Localization. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31208–31216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Qi, Y.; Hu, H. Cellular and Molecular Characterization of Abnormal Brain Development in Protein O-Mannose N-Acetylglucosaminyltransferase 1 Knockout Mice. Methods Enzymol. 2010, 479, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, M. Pikachurin Interaction with Dystroglycan Is Diminished by Defective O-Mannosyl Glycosylation in Congenital Muscular Dystrophy Models and Rescued by LARGE Overexpression. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 489, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, M.; Feng, G.; Hu, H.; Li, X. Breaches of the Pial Basement Membrane Are Associated with Defective Dentate Gyrus Development in Mouse Models of Congenital Muscular Dystrophies. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 505, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Kanesaki, H.; Igarashi, T.; Kameya, S.; Yamaki, K.; Mizota, A.; Kudo, A.; Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y.; Takeda, S.; Takahashi, H. Reactive Gliosis of Astrocytes and Müller Glial Cells in Retina of POMGnT1-Deficient Mice. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2011, 47, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; He, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, S.; Hu, H. Adeno-Associated Viral-Mediated LARGE Gene Therapy Rescues the Muscular Dystrophic Phenotype in Mouse Models of Dystroglycanopathy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2013, 24, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yang, Y.; Candiello, J.; Thorn, T.L.; Gray, N.; Halfter, W.M.; Hu, H. Biochemical and Biophysical Changes Underlie the Mechanisms of Basement Membrane Disruptions in a Mouse Model of Dystroglycanopathy. Matrix Biol. 2013, 32, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booler, H.S.; Williams, J.L.; Hopkinson, M.; Brown, S.C. Degree of Cajal-Retzius Cell Mislocalization Correlates with the Severity of Structural Brain Defects in Mouse Models of Dystroglycanopathy. Brain Pathol. 2016, 26, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, S.; Sakaguchi, H.; Mohri, H.; Taniguchi-Ikeda, M.; Kanagawa, M.; Suzuki, T.; Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y.; Toda, T.; Saito, N.; Ueyama, T. Congenital Hearing Impairment Associated with Peripheral Cochlear Nerve Dysmyelination in Glycosylation-Deficient Muscular Dystrophy. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1008826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, L.; Esteve-Rudd, J.; Bru-Martínez, R.; Herrero, M.T.; Fernández-Villalba, E.; Cuenca, N.; Martín-Nieto, J. Alterations in Energy Metabolism, Neuroprotection and Visual Signal Transduction in the Retina of Parkinsonian, MPTP-Treated Monkeys. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Esteve-Rudd, J.; Fernández-Sánchez, L.; Lax, P.; De Juan, E.; Martín-Nieto, J.; Cuenca, N. Rotenone Induces Degeneration of Photoreceptors and Impairs the Dopaminergic System in the Rat Retina. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 44, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, A.A.; James, R.E.; Swanson, P.; Carvalho, L.S. A Review of the 661W Cell Line as a Tool to Facilitate Treatment Development for Retinal Diseases. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ubaidi, M.R.; Font, R.L.; Quiambao, A.B.; Keener, M.J.; Liou, G.I.; Overbeek, P.A.; Baehr, W. Bilateral Retinal and Brain Tumors in Transgenic Mice Expressing Simian Virus 40 Large T Antigen Under Control of the Human Interphotoreceptor Retinoid-Binding Protein promoter. J. Cell Biol. 1992, 119, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E.; Ding, X.Q.; Saadi, A.; Agarwal, N.; Naash, M.I.; Al-Ubaidi, M.R. Expression of Cone-Photoreceptor-Specific Antigens in a Cell Line Derived From Retinal Tumors in Transgenic Mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, Y.; Moiseyev, G.; Agarwal, N.; Ma, J.X.; Al-Ubaidi, M.R. Light Induces Programmed Cell Death by Activating Multiple Independent Proteases in a Cone Photoreceptor Cell Line. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ubaidi, M.R.; Matsumoto, H.; Kurono, S.; Singh, A. Proteomics Profiling of the Cone Photoreceptor Cell Line, 661W. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008, 613, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, C.; Uribe, M.L.; Quereda, C.; Cruces, J.; Martín-Nieto, J. Expression in Retinal Neurons of Fukutin and FKRP, the Protein Products of Two Dystroglycanopathy-Causative Genes. Mol. Vis. 2018, 24, 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Navarrete, G.C.; Martín-Nieto, J.; Esteve-Rudd, J.; Angulo, A.; Cuenca, N. α-Synuclein Gene Expression Profile in the Retina of Vertebrates. Mol. Vis. 2007, 13, 949–961. [Google Scholar]

- Combs, A.C.; Ervasti, J.M. Enhanced Laminin Binding by α-Dystroglycan After Enzymatic Deglycosylation. Biochem. J. 2005, 390, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve-Rudd, J.; Campello, L.; Herrero, M.T.; Cuenca, N.; Martín-Nieto, J. Expression in the Mammalian Retina of Parkin and UCH-L1, Two Components of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. Brain Res. 2010, 1352, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manders, E.M.M.; Stap, J.; Brakenhoff, G.J.; van Driel, R.; Aten, J.A. Dynamics of Three-Dimensional Replication Patterns During the S-Phase, Analysed by Double Labelling of DNA and Confocal Microscopy. J. Cell Sci. 1992, 103, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolte, S.; Cordelières, F.P. A Guided Tour Into Subcellular Colocalization Analysis in Light Microscopy. J. Microsc. 2006, 224, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Mitra, S.; McBride, J.W. Ehrlichia chaffeensis TRP75 Interacts with Host Cell Targets Involved in Homeostasis, Cytoskeleton Organization, and Apoptosis Regulation to Promote Infection. mSphere 2018, 3, e00147-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielinska, D.F.; Gnad, F.; Wiśniewski, J.R.; Mann, M. Precision Mapping of an In Vivo N-Glycoproteome Reveals Rigid Topological and Sequence Constraints. Cell 2010, 141, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steentoft, C.; Vakhrushev, S.Y.; Joshi, H.J.; Kong, Y.; Vester-Christensen, M.B.; Schjoldager, K.T.B.G.; Lavrsen, K.; Dabelsteen, S.; Pedersen, N.B.; Marcos-Silva, L.; et al. Precision Mapping of the Human O-GalNAc Glycoproteome Through SimpleCell Technology. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeshi, N.D.; Svinkina, T.; Mertins, P.; Kuhn, E.; Mani, D.R.; Qiao, J.W.; Carr, S.A. Refined Preparation and Use of Anti-Diglycine Remnant (K-ε-GG) Antibody Enables Routine Quantification of 10,000s of Ubiquitination Sites in Single Proteomics Experiments. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2013, 12, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napier, R.M.; Fowke, L.C.; Hawes, C.; Lewis, M.; Pelham, H.R.B. Immunological Evidence that Plants Use Both HDEL and KDEL for Targeting Proteins to the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J. Cell Sci. 1992, 102, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, N.; Rabouille, C.; Watson, R.; Nilsson, T.; Hui, N.; Slusarewicz, P.; Kreis, T.E.; Warren, G. Characterization of a cis-Golgi Matrix Protein, GM130. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 131, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Rosa, H.; Schneider, R.; Bannister, A.; Sherriff, J.; Bernstein, B.; Emre, N.; Schreiber, S.; Mellor, J.; Kouzarides, T. Active Genes are Tri-Methylated at K4 of Histone H3. Nature 2002, 419, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowell, I.G.; Aucott, R.; Mahadevaiah, S.K.; Burgoyne, P.S.; Huskisson, N.; Bongiorni, S.; Prantera, G.; Fanti, L.; Pimpinelli, S.; Wu, R.; et al. Heterochromatin, HP1 and Methylation at Lysine 9 of Histone H3 in Animals. Chromosoma 2002, 111, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisvert, F.M.; Van Koningsbruggen, S.; Navascués, J.; Lamond, A.I. The Multifunctional Nucleolus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, R.L.; Lischwe, M.A.; Spohn, W.H.; Busch, H. Fibrillarin: A New Protein of the Nucleolus Identified by Autoimmune Sera. Biol. Cell 1985, 54, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarz, P.; Santos-Rosa, H.; Robson, S.C.; Sylvestersen, K.B.; Nelson, C.J.; Nielsen, M.L.; Kouzarides, T. Glutamine Methylation in Histone H2A Is an RNA-Polymerase-I-Dedicated Modification. Nature 2014, 505, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer-Bierhoff, A.; Krogh, N.; Tessarz, P.; Ruppert, T.; Nielsen, H.; Grummt, I. SIRT7-Dependent Deacetylation of Fibrillarin Controls Histone H2A Methylation and rRNA Synthesis During the Cell Cycle. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2946–2954.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Lallemand-Breitenbach, V.; De Thé, H. PML Nuclear Bodies: Regulation, Function and Therapeutic Perspectives. J. Pathol. 2014, 234, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, K.L.B. Pondering the Promyelocytic Leukemia Protein (PML) Puzzle: Possible Functions for PML Nuclear Bodies. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 5259–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, J.G. The Centennial of the Cajal Body. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo-Fonseca, M.; Ferreira, J.; Lamond, A.I. Assembly of snRNP-Containing Coiled Bodies Is Regulated in Interphase and Mitosis–Evidence that the Coiled Body Is a Kinetic Nuclear Structure. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 120, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azubel, M.; Wolf, S.G.; Sperling, J.; Sperling, R. Three-Dimensional Structure of the Native Spliceosome by Cryoelectron Microscopy. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Will, C.L.; Lührmann, R. Spliceosome Structure and Function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a003707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, C.; Hang, J.; Finci, L.I.; Lei, J.; Shi, Y. An Atomic Structure of the Human Spliceosome. Cell 2017, 169, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados, B.; Peña, A.; Cotarelo, R.P.; Valero, M.C.; Cruces, J. Expression of the Murine Pomt1 Gene in Both the Developing Brain and Adult Muscle Tissues and its Relationship with Clinical Aspects of Walker-Warburg Syndrome. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Fernández, M.; Uribe, M.L.; Vicente-Tejedor, J.; Germain, F.; Susín-Lara, C.; Quereda, C.; Montoliu, L.; de la Villa, P.; Martín-Nieto, J.; Cruces, J. Impairment of Photoreceptor Ribbon Synapses in a Novel Pomt1 Conditional Knockout Mouse Model of Dystroglycanopathy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campello, L.; Martín-Nieto, J. RNA-Seq Expression Profile of Genes Related to Neurodegenerative Disorders Affecting the Human Retina. EMBnet J. 2013, 19, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Halmo, S.M.; Praissman, J.; Chapla, D.; Singh, D.; Wells, L.; Moremen, K.W.; Lanzilotta, W.N. Crystal Structures of β-1,4-N-Acetylglucosaminyl-Transferase 2: Structural Basis for Inherited Muscular Dystrophies. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2021, 77, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagawa, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Tajiri, M.; Manya, H.; Kuga, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Akasaka-Manya, K.; Furukawa, J.; Mizuno, M.; Kawakami, H.; et al. Identification of a Post-Translational Modification with Ribitol-Phosphate and Its Defect in Muscular Dystrophy. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 2209–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagawa, M.; Toda, T. Muscular Dystrophy with Ribitol-Phosphate Deficiency: A Novel Post-Translational Mechanism in Dystroglycanopathy. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2017, 4, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagawa, M.; Toda, T. Ribitol-Phosphate—A Newly Identified Posttranslational Glycosylation Unit in Mammals: Structure, Modification Enzymes and Relationship to Human Diseases. J. Biochem. 2018, 163, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, T.; Inamori, K.; Venzke, D.; Harvey, C.; Morgensen, G.; Hara, Y.; Beltrán Valero de Bernabé, D.; Yu, L.; Wright, K.; Campbell, K. The Glucuronyltransferase B4GAT1 Is Required for Initiation of LARGE-Mediated α-Dystroglycan Functional Glycosylation. ELife 2014, 3, e03941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishihara, R.; Kobayashi, K.; Imae, R.; Tsumoto, H.; Manya, H.; Mizuno, M.; Kanagawa, M.; Endo, T.; Toda, T. Cell Endogenous Activities of Fukutin and FKRP Coexist with the Ribitol Xylosyltransferase, TMEM5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 497, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esapa, C.T.; Benson, M.A.; Schröder, J.E.; Martin-Rendon, E.; Brockington, M.; Brown, S.C.; Muntoni, F.; Kröger, S.; Blake, D.J. Functional Requirements for Fukutin-Related Protein in the Golgi Apparatus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 3319–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Noguchi, S.; Sugie, K.; Ogawa, M.; Murayama, K.; Hayashi, Y.K.; Nishino, I. Subcellular Localization of Fukutin and Fukutin-Related Protein in Muscle Cells. J. Biochem. 2004, 135, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Kato, Y.; Shibata, N.; Sawada, T.; Osawa, M.; Kobayashi, M. A Role of Fukutin, a Gene Responsible for Fukuyama Type Congenital Muscular Dystrophy, in Cancer Cells: A Possible Role to Suppress Cell Proliferation. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2008, 89, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Shibata, N.; Saito, Y.; Osawa, M.; Kobayashi, M. Functions of Fukutin, a Gene Responsible for Fukuyama Type Congenital Muscular Dystrophy, in Neuromuscular System and Other Somatic Organs. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamidi, M.; Kjeldsen Buvang, E.; Fagerheim, T.; Brox, V.; Lindal, S.; Van Ghelue, M.; Nilssen, Ø. Fukutin-Related Protein Resides in the Golgi Cisternae of Skeletal Muscle Fibres and Forms Disulfide-Linked Homodimers Via an N-Terminal Interaction. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dolatshad, N.F.; Brockington, M.; Torelli, S.; Skordis, L.; Wever, U.; Wells, D.J.; Muntoni, F.; Brown, S.C. Mutated Fukutin-Related Protein (FKRP) Localises as Wild Type in Differentiated Muscle Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2005, 309, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramaris-Vrantsis, E.; Lu, P.J.; Doran, T.; Zillmer, A.; Ashar, J.; Esapa, C.T.; Benson, M.A.; Blake, D.J.; Rosenfeld, J.; Lu, Q.L. Fukutin-Related Protein Localizes to the Golgi Apparatus and Mutations Lead to Mislocalization in Muscle In Vivo. Muscle Nerve 2007, 36, 455–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, S.; Brown, S.C.; Brockington, M.; Dolatshad, N.F.; Jimenez, C.; Skordis, L.; Feng, L.H.; Merlini, L.; Jones, D.H.; Romero, N.; et al. Sub-Cellular Localisation of Fukutin Related Protein in Different Cell Lines and in the Muscle of Patients with MDC1C and LGMD2I. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2005, 15, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Yamada, T.; Sun, Z.; Eblimit, A.; Lopez, I.; Wang, F.; Manya, H.; Xu, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Mutations in POMGNT1 Cause Non-Syndromic Retinitis Pigmentosa. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koulen, P.; Honig, L.S.; Fletcher, E.L.; Kröger, S. Expression, Distribution and Ultrastructural Localization of the Synapse-Organizing Molecule Agrin in the Mature Avian Retina. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 4188–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krizaj, D.; Copenhagen, D.R. Calcium Regulation in Photoreceptors. Front. Biosci. 2002, 7, d2023–d2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tan, G.; Levenkova, N.; Li, T.; Pugh, E.N.; Rux, J.J.; Speichers, D.W.; Pierce, E.A. The Proteome of the Mouse Photoreceptor Sensory Cilium Complex. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2007, 6, 1299–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.R.; Fliesler, S.J.; Al-Ubaidi, M.R. Rhodopsin: The Functional Significance of Asn-Linked Glycosylation and Other Post-Translational Modifications. Ophthalmic Genet. 2009, 30, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, B.D.; Fadool, J.M. Photoreceptor Structure and Development: Analyses Using GFP Transgenes. Methods Cell Biol. 2010, 100, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeger, H.; Chiang, W.C.; Lin, J.H. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation (ERAD) of Misfolded Glycoproteins and Mutant P23H Rhodopsin in Photoreceptor Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 723, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.A.; Kerov, V. Photoreceptor Inner and Outer Segments. Curr. Top. Membr. 2013, 72, 231–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baehr, W. Membrane Protein Transport in Photoreceptors: The Function of PDEδ. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 8653–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, N.; Fernández-Sánchez, L.; Campello, L.; Maneu, V.; De la Villa, P.; Lax, P.; Pinilla, I. Cellular Responses Following Retinal Injuries and Therapeutic Approaches for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2014, 43, 17–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Anand, M.; Rao, K.N.; Khanna, H. Cilia in Photoreceptors. Methods Cell Biol. 2015, 125, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujakowska, K.M.; Liu, Q.; Pierce, E.A. Photoreceptor Cilia and Retinal Ciliopathies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a028274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May-Simera, H.; Nagel-Wolfrum, K.; Wolfrum, U. Cilia–The Sensory Antennae in the Eye. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 60, 144–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, D.S.; Chidlow, G.; Wood, J.P.M.; Casson, R.J. Glucose Metabolism in Mammalian Photoreceptor Inner and Outer Segments. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2017, 45, 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Datta, P. Photoreceptor Outer Segment as a Sink for Membrane Proteins: Hypothesis and Implications in Retinal Ciliopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, R75–R82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baehr, W.; Hanke-Gogokhia, C.; Sharif, A.; Reed, M.; Dahl, T.; Frederick, J.M.; Ying, G. Insights Into Photoreceptor Ciliogenesis Revealed by Animal Models. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2019, 71, 26–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanishi, Y. Protein Sorting in Healthy and Diseased Photoreceptors. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2019, 5, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.J.; Tracey-White, D.; Kam, J.H.; Powner, M.B.; Jeffery, G. The 3D Organisation of Mitochondria in Primate Photoreceptors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protein | Antibody | Company | Catalog No. | Working Dilution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IB | IHC | ICC | ||||

| POMGNT2 | Rabbit, polyclonal | Thermo Fisher Scientific a | PA5-43262 | 1:500 | – | – |

| POMGNT2 | Rabbit, polyclonal | Signalway Antibody b | 38956 | – | 1:100 | 1:100 |

| POMGNT1 | Mouse, clone 6C12 | Sigma-Aldrich c | WH0055624M7 | – | 1:50 | 1:50 |

| POMGNT1 | Rabbit, polyclonal | Thermo Fisher Scientific | PA5-76448 | – | 1:100 | 1:100 |

| β-Tubulin III | Rabbit, polyclonal | Sigma-Aldrich | T3952 | 1:500 | – | – |

| Lamina A/C | Mouse, clone 4C11 | Sigma-Aldrich | SAB200236 | 1:1000 | – | – |

| KDEL | Mouse, clone 10C3 | Abcam d | ab12223 | – | 1:100 | 1:100 |

| GM130 | Mouse, clone 35 | BD Transduction Laboratories e | 610822 | – | 1:100 | 1:100 |

| GM130 | Rabbit, polyclonal | Thermo Fisher Scientific | PA5-85643 | – | 1:100 | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quereda, C.; Gómez-Vicente, V.; Palmero, M.; Martín-Nieto, J. Expression of Dystroglycanopathy-Related Enzymes, POMGNT2 and POMGNT1, in the Mammalian Retina and 661W Cone-like Cell Line. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112759

Quereda C, Gómez-Vicente V, Palmero M, Martín-Nieto J. Expression of Dystroglycanopathy-Related Enzymes, POMGNT2 and POMGNT1, in the Mammalian Retina and 661W Cone-like Cell Line. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112759

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuereda, Cristina, Violeta Gómez-Vicente, Mercedes Palmero, and José Martín-Nieto. 2025. "Expression of Dystroglycanopathy-Related Enzymes, POMGNT2 and POMGNT1, in the Mammalian Retina and 661W Cone-like Cell Line" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112759

APA StyleQuereda, C., Gómez-Vicente, V., Palmero, M., & Martín-Nieto, J. (2025). Expression of Dystroglycanopathy-Related Enzymes, POMGNT2 and POMGNT1, in the Mammalian Retina and 661W Cone-like Cell Line. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2759. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112759