Isotopic H/D Exchange in Hydrogen Bonds Between the Nitrogenous Bases of the CAG Repeat Tract Makes It Possible to Stabilize Its Expansion in the ATXN2 Gene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mathematical Model

2.2. Description of the Numerical Experiment

2.3. Calculating the Probabilities of Open States Formation

3. Results and Discussion

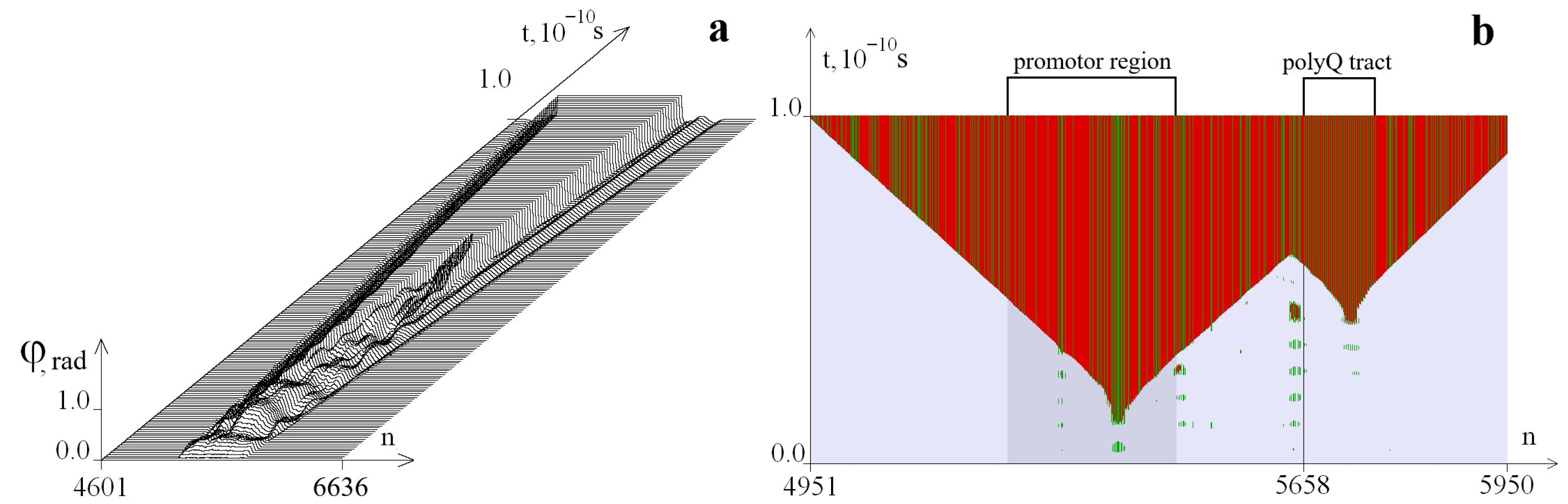

3.1. Examples of Additional OS Zones Formation in the CAG Repeat Tract

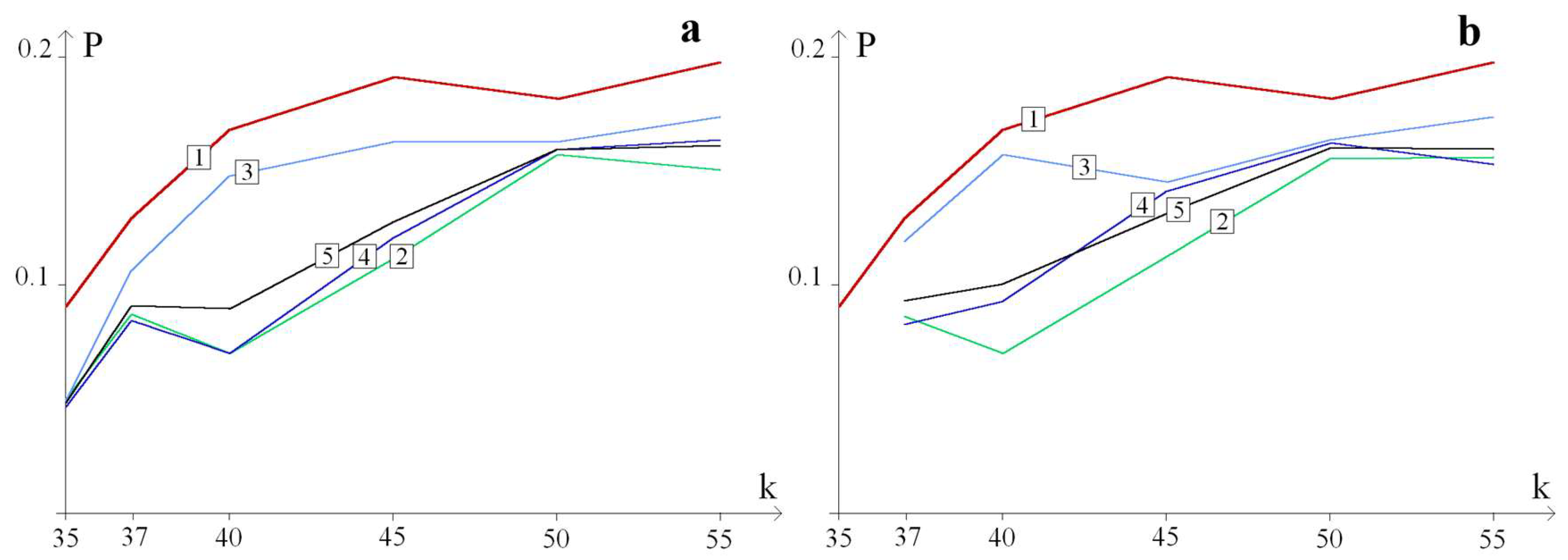

3.2. The Probability of Additional Large OSs Zone Formation Depending on the Localization of the H/D Substitution in the CAG Repeat Tract

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| polyQ | polyglutamine tract |

| H/D | protium/deuterium |

| OSs | open states |

References

- Velázquez-Pérez, L.; Cruz, G.S.; Santos-Falcón, N.; Almaguer-Gotay, D.; Cedeño, H.J. Molecular epidemiology of spinocerebellar ataxias in Cuba: Insights into SCA2 founder effect in Holguin. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 454, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, S.; Wen, J.; Scoles, D.R.; Simeonov, A.; Dexheimer, T.S.; Jadhav, A.; Kales, S.C.; Sun, H.; Pulst, S.M.; Facelli, J.C.; et al. Identifying Molecular Properties of Ataxin-2 Inhibitors for Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 Utilizing High-Throughput Screening and Machine Learning. Biology 2025, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulst, S.M. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2: A Review and Personal Perspective. Neurol. Gen. 2025, 11, e200225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.G.; Conceição, A.; Matos, C.A.; Nóbrega, C. The polyglutamine protein ATXN2: From its molecular functions to its involvement in disease. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, H. Repeat expansion diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 147, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, A.L.; L’Italien, G.; Perlman, S.L.; Rosenthal, L.S.; Kuo, S.H.; Ashizawa, T.; Zesiewicz, T.; Dietiker, C.; Opal, P.; Duquette, A.; et al. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Progression Measured with the Patient-Reported Outcome Measure of Ataxia. Mov. Disord. 2025, 40, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.B.; Park, S.M.; Jung, U.J.; Kim, S.R. The Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Treating Spinocerebellar Ataxia: Advances and Future Directions. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X. The Role of Protein Quantity Control in Polyglutamine Spinocerebellar Ataxias. Cerebellum 2024, 23, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinina, K.S.; Bezprozvanny, I.B.; Egorova, P.A. Cognitive Decline and Mood Alterations in the Mouse Model of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2. Cerebellum 2024, 23, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Lai, R.Y.; Fadel, Z.; Lin, Y.; Parekh, P.; Griep, R.; Pan, M.K.; Kuo, S.H. Cerebello-Prefrontal Connectivity Underlying Cognitive Dysfunction in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2025, 12, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoles, D.R.; Pulst, S.M. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1049, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Pérez, L.; Rodríguez-Labrada, R.; Torres-Vega, R.; Medrano Montero, J.; Vázquez-Mojena, Y.; Auburger, G.; Ziemann, U. Abnormal corticospinal tract function and motor cortex excitability in non-ataxic SCA2 mutation carriers: A TMS study. Clin. Neurophys. 2016, 127, 2713–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, C.F.; Jaques, C.S.; Escorcio-Bezerra, M.L.; Pedroso, J.L.; Barsottini, O.G.P. Respiratory Evaluation in Spinocerebellar ataxia Type 2. Cerebellum 2025, 24, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osadchuk, L.; Vasiliev, G.; Kleshchev, M.; Osadchuk, A. Androgen Receptor Gene CAG Repeat Length Varies and Affects Semen Quality in an Ethnic-Specific Fashion in Young Men from Russia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, C.S.; Li, D.; Wilton, S.D.; Aung-Htut, M.T. Polyglutamine Ataxias: Our Current Molecular Understanding and What the Future Holds for Antisense Therapies. Biomedicines 2011, 9, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrowski, L.A.; Hall, A.C.; Mekhail, K. Ataxin-2: From RNA Control to Human Health and Disease. Genes 2017, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Li, W.; Liu, P.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Ni, J.; Shen, L.; Tang, B.; Wang, J. The Clinical and Polynucleotide Repeat Expansion Analysis of ATXN2, NOP56, AR and C9orf72 in Patients With ALS From Mainland China. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 811202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Pérez, L.; Medrano-Montero, J.; Rodríguez-Labrada, R.; Canales-Ochoa, N.; Campins Alí, J.; Carrillo Rodes, F.J.; Rodríguez Graña, T.; Hernández Oliver, M.O.; Aguilera Rodríguez, R.; Domínguez Barrios, Y.; et al. Hereditary Ataxias in Cuba: A Nationwide Epidemiological and Clinical Study in 1001 Patients. Cerebellum 2020, 19, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, L.S.; Dos Santos Pinheiro, J.; Hasan, A.; Saraiva-Pereira, M.L.; Jardim, L.B. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 from an evolutionary perspective: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Genet. 2021, 100, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhang, J.; Pan, F.; Mahn, C.; Roland, C.; Sagui, C.; Weninger, K. Frustration Between Preferred States of Complementary Trinucleotide Repeat DNA Hairpins Anticorrelates with Expansion Disease Propensity. J. Mol. Biol. 2023, 435, 168086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.C.; Tan, Y.L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.G.; Shi, Y.Z. Computational Modeling of DNA 3D Structures: From Dynamics and Mechanics to Folding. Molecules 2023, 28, 4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos-Rodrigues, G.; Hisey, J.A.; Nussenzweig, A.; Mirkin, S.M. Detection of alternative DNA structures and its implications for human disease. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 3622–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.; Donaldson, J.; Flower, M.; Hensman Moss, D.J.; Tabrizi, S.J. Genetic Modifiers of Repeat Expansion Disorders. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2023, 7, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tevonyan, L.L.; Beniaminov, A.D.; Kaluzhny, D.N. Quenching of G4-DNA intrinsic fluorescence by ligands. Euro. Biophys. J. 2024, 53, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anashkina, A.A. Protein-DNA recognition mechanisms and specificity. Biophys. Rev. 2023, 15, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobotenko, M.I.; Lyasota, O.M.; Hernandez-Caceres, J.L.; Rodriguez-Labrada, R.; Svidlov, A.A.; Dorohova, A.A.; Baryshev, M.G.; Nechipurenko, Y.D.; Velázquez-Pérez, L.; Dzhimak, S.S. Abnormal open states patterns in the ATXN2 DNA sequence depends on the CAG repeats length. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, P.; Camuzat, A.; Benammar, N.; Sellal, F.; Destée, A.; Bonnet, A.M.; Lesage, S.; Le Ber, I.; Stevanin, G.; Dürr, A.; et al. French Parkinson’s Disease Genetic Study Group. Are interrupted SCA2 CAG repeat expansions responsible for parkinsonism? Neurology 2007, 69, 1970–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Chen-Plotkin, A.S.; Clay-Falcone, D.; McCluskey, L.; Elman, L.; Kalb, R.G.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.; Van Deerlin, V.M.; et al. PolyQ Repeat Expansions in ATXN2 Associated with ALS Are CAA Interrupted Repeats. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Predtechenskaya, E.V.; Rogachev, A.D.; Melnikova, P.M. The Characteristics of the Metabolomic Profile in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Vascular Parkinsonism. Acta Naturae 2024, 16, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira de Sá, R.; Sudria-Lopez, E.; Cañizares Luna, M.; Harschnitz, O.; van den Heuvel, D.M.A.; Kling, S.; Vonk, D.; Westeneng, H.-J.; Karst, H.; Bloemenkamp, L.; et al. ATAXIN-2 intermediate-length polyglutamine expansions elicit ALS-associated metabolic and immune phenotypes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrego-Hernández, D.; Vázquez-Costa, J.F.; Domínguez-Rubio, R.; Expósito-Blázquez, L.; Aller, E.; Padró-Miquel, A.; Gar-cía-Casanova, P.; Colomina, M.J.; Martín-Arriscado, C.; Osta, R.; et al. Intermediate Repeat Expansion in the ATXN2 Gene as a Risk Factor in the ALS and FTD Spanish Population. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Xu, P.; Roland, C.; Sagui, C.; Weninger, K. Structural and Dynamical Properties of Nucleic Acid Hairpins Implicated in Trinucleotide Repeat Expansion Diseases. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, P.; Man, V.H.; Roland, C.; Weninger, K.; Sagui, C. Molecular conformations and dynamics of nucleotide repeats associated with neurodegenerative diseases: Double helices and CAG hairpin loops. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 2819–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Morten, M.J.; Magennis, S.W. Conformational and migrational dynamics of slipped-strand DNA three-way junctions containing trinucleotide repeats. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadden, G.M.; Wilken, S.J.; Magennis, S.W. A single CAA interrupt in a DNA three-way junction containing a CAG repeat hairpin results in parity-dependent trapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 9317–9327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kompella, P.; Wang, G.; Durrett, R.E.; Lai, Y.; Marin, C.; Liu, Y.; Habib, S.L.; DiGiovanni, J.; Vasquez, K.M. Obesity increases genomic instability at DNA repeat-mediated endogenous mutation hotspots. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyasota, O.; Dorohova, A.; Hernandez-Caceres, J.L.; Svidlov, A.; Tekutskaya, E.; Drobotenko, M.; Dzhimak, S. Stability of the CAG Tract in the ATXN2 Gene Depends on the Localization of CAA Interruptions. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Kaushik, S.; Kukreti, S. Non-canonical DNA structures: Diversity and disease association. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 959258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, S.D.; Bowleg, J.L.; Gwaltney, S.R. Computational modeling to understand the interaction of TMPyP4 with a G-quadruplex. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, K.; Krzyzosiak, W.J. CAG Repeats Containing CAA Interruptions Form Branched Hairpin Structures in Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 Transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 3898–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmann, A.E.; Patel, M.; Jeong, S.Y.; Bartom, E.T.; Morton, A.J.; Peter, M.E. The length of uninterrupted CAG repeats in stem regions of repeat disease associated hairpins determines the amount of short CAG oligonucleotides that are toxic to cells through RNA interference. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobotenko, M.I.; Velázquez-Pérez, L.; Dorohova, A.A.; Lyasota, O.M.; Hernandez-Caceres, J.L.; Rodriguez-Labrada, R.; Svidlov, A.A.; Leontyeva, O.A.; Baryshev, M.G.; Nechipurenko, Y.D.; et al. Genesis of additional open state zones in the extended CAG repeat tract of the ATXN2 gene depends on its length and interruptions localization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 772, 110531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Pan, F.; Roland, C.; Sagui, C.; Weninger, K. Dynamics of strand slippage in DNA hairpins formed by CAG repeats: Roles of sequence parity and trinucleotide interrupts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 2232–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, J.; Breslauer, K.J. How sequence alterations enhance the stability and delay expansion of DNA triplet repeat domains. QRB Discov. 2023, 4, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmon, V.N. On the possibility of observing kinetic isotopic effects in the life cycles of living organisms at ultralow concentrations of deuterium. Her. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2015, 85, 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhimak, S.S.; Drobotenko, M.I.; Dorohova, A.A. Coarse-grained mathematical models for studying mechanical properties of the DNA. Biophys. Rev. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manghi, M.; Destainville, N. Physics of base-pairing dynamics in DNA. Phys. Rep. 2016, 631, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevizovich, D.; Zdravkovic, S.; Michieletto, D.; Mvogo, A.; Zakiryanov, F. A review on nonlinear DNA physics. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitiuk, A.S.; Burmistrova, O.S.; Naimark, O.B. Study of the DNA denaturation based on the Peyrard-Bishop-Dauxois model and recurrence quantification analysis. Russ. J. Biomech. 2022, 26, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, M. Base-Pairing and Base-Stacking Contributions to Double-Stranded DNA Formation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020, 124, 10345–10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, Y. Theoretical Model of Transcription Based on Torsional Mechanics of DNA Template. J. Stat. Phys. 2019, 174, 1316–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englander, S.W.; Kallenbach, N.R.; Heeger, A.J.; Krumhansl, J.A.; Litwin, S. Nature of the open state in long polynucleotide double helices: Possibility of soliton excitations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 7222–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakushevich, L.V. Nonlinear Physics of DNA; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; p. 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobotenko, M.I.; Dzhimak, S.S.; Svidlov, A.A.; Basov, A.A.; Lyasota, O.M.; Baryshev, M.G. A Mathematical Model for Basepair Opening in a DNA Double Helix. Biophysics 2018, 63, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitiuk, A.; Bayandin, Y.; Naimark, O. Study of Nonlinear Dynamic Modes of Native DNA via Mathematical Modeling Methods. Rus. J. Biomech. 2023, 27, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, M.; Kalosakas, G.; Bishop, A.R.; Skokos, C. Bubble Lifetimes in DNA Gene Promoters and Their Mutations Affecting Transcription. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 095101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantawy, M.; Abdel-Gawad, H.I. Dynamics of Molecules in Torsional DNA Exposed to Microwave and Possible Impact on Its Deformation: Stability Analysis. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masulis, I.; Grinevich, A.; Yakushevich, L. Dynamics of Open States and Promoter Functioning in the appY_red and appY_green Genetic Constructions Based on the pPF1 Plasmid. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2024, 29, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svidlov, A.A.; Drobotenko, M.I.; Basov, A.A.; Dzhimak, S.S.; Baryshev, M.G. Influence of the 2H/1H Isotope Composition of the Water Environment on the Probability of Denaturation Bubble Formation in a DNA Molecule. Phys. Wave Phenom. 2021, 29, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhimak, S.S.; Drobotenko, M.I.; Basov, A.A.; Svidlov, A.A.; Fedulova, L.V.; Lyasota, O.M.; Baryshev, M.G. Mathematical Modeling of Open State in DNA Molecule Depending on the Deuterium Concentration in the Surrounding Liquid Media at Different Values of Hydrogen Bond Disruption Energy. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 483, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svidlov, A.; Drobotenko, M.; Basov, A.; Nechipurenko, Y.; Dzhimak, S. Influence of Environmental Parameters on the Stability of the DNA Molecule. Entropy 2021, 23, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobotenko, M.; Svidlov, A.; Dorohova, A.; Baryshev, M.; Dzhimak, S. Medium Viscosity Influence on the Open States Genesis in a DNA Molecule. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 43, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyasota, O.M.; Dorofhova, A.A.; Drobotenko, M.I.; Dzhimak, S.S. Program for Calculating Open States in DNA Sequence Depending on the Length of Trinucleotide Repeats. Certificate of Registration of the Computer Program RU 2025618875, 8 April 2025. Application No. 2025617199 dated 4 January 2025. Available online: https://www1.fips.ru/iiss/document.xhtml?faces-redirect=true&id=03dcaeec453d38c8cf2d4c9380ccd22a (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Ma, J.; Bai, L.; Wang, M.D. Transcription under Torsion. Science 2013, 340, 1580–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhimak, S.; Svidlov, A.; Elkina, A.; Gerasimenko, E.; Baryshev, M.; Drobotenko, M. Genesis of Open States Zones in a DNA Molecule Depends on the Localization and Value of the Torque. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Pérez, L.; Rodríguez-Labrada, R.; García-Rodríguez, J.C.; Almaguer-Mederos, L.E.; Cruz-Mariño, T.; Laffita-Mesa, J.M. A Comprehensive Review of Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 in Cuba. Cerebellum 2011, 10, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hou, X.; Chen, Z.; Shen, L.; Xia, K.; Tang, B.; Jiang, H.; Wang, J. Effect of CAG Repeats on the Age at Onset of Patients with Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 2 in China. J. Cent. South Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 46, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, A.A.; McMurray, C.T. Close Encounters: Moving along Bumps, Breaks, and Bubbles on Expanded Trinucleotide Tracts. DNA Repair 2017, 56, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grishchenko, I.V.; Purvinsh, Y.V.; Yudkin, D.V. Mystery of Expansion: DNA Metabolism and Unstable Repeats. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1241, pp. 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidle, S. Beyond the Double Helix: DNA Structural Diversity and the PDB. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobotenko, M.; Lyasota, O.; Dzhimak, S.; Svidlov, A.; Baryshev, M.; Leontyeva, O.; Dorohova, A. Localization of Potential Energy in Hydrogen Bonds of the ATXN2 Gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niewiadomska-Cimicka, A.; Fievet, L.; Surdyka, M.; Jesion, E.; Keime, C.; Singer, E.; Eisenmann, A.; Kalinowska-Poska, Z.; Nguyen, H.H.P.; Fiszer, A.; et al. AAV-Mediated CAG-Targeting Selectively Reduces Polyglutamine-Expanded Protein and Attenuates Disease Phenotypes in a Spinocerebellar Ataxia Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, R.; Stolyarova, A.; Zalevsky, A.; Panteleev, D.Y.; Pavlova, G.V.; Klinov, D.V.; Golovin, A.V.; Protopopova, A.D. A coarse-grained model for DNA origami. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank-Kamenetskii, M.D.; Prakash, S. Fluctuations in the DNA double helix: A critical review. Phys. Life Rev. 2014, 11, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, F.; Destainville, N.; Rousseau, P.; Tardin, C.; Manghi, M. Dynamical control of denaturation bubble nucleation in supercoiled DNA minicircles. Phys. Rev. E 2020, 101, 012403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forth, S.; Sheinin, M.Y.; Inman, J.; Wang, M.D. Torque measurement at the single-molecule level. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2013, 42, 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigaev, A.S.; Ponomarev, O.A.; Lakhno, V.D. Theoretical and experimental investigations of DNA open states. Math. Biol. Bioinf. 2018, 8, t162–t267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Répás, Z.; Győri, Z.; Buzás-Bereczki, O.; Boros, L. The biological effects of deuterium present in food. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaglova, N.V.; Obernikhin, S.S.; Timokhina, E.P.; Tsomartova, E.S.; Yaglov, V.V.; Nazimova, S.V.; Ivanova, M.Y.; Chereshneva, E.V.; Lomanovskaya, T.A.; Tsomartova, D.A. Altering the Hydrogen Isotopic Composition of the Essential Nutrient Water as a Promising Tool for Therapy: Perspectives and Risks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basov, A.; Fedulova, L.; Baryshev, M.; Dzhimak, S. Deuterium-Depleted Water Influence on the Isotope 2H/1H Regulation in Body and Individual Adaptation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, R.A. Role of stable isotopes in life—Testing isotopic resonance hypothesis. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2011, 9, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basov, A.; Fedulova, L.; Vasilevskaya, E.; Dzhimak, S. Possible Mechanisms of Biological Effects Observed in Living Systems during 2H/1H Isotope Fractionation and Deuterium Interactions with Other Biogenic Isotopes. Molecules 2019, 24, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, L.G.; Bartolotti, L.; Li, L. Deuterium and its role in the machinery of evolution. J. Theor. Biol. 2006, 238, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozin, S.V.; Lyasota, O.M.; Kravtsov, A.A.; Chikhirzhina, E.V.; Ivlev, V.A.; Popov, K.A.; Dorohova, A.A.; Malyshko, V.V.; Moiseev, A.V.; Drozdov, A.V.; et al. Shift of Prooxidant—Antioxidant Balance in Laboratory Animals at Five Times Higher Deuterium Content in Drinking Water. Biophysics 2023, 68, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchepinov, M.S. Do “heavy” eaters live longer? BioEssays 2007, 29, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zubarev, R.A. Effects of low-level deuterium enrichment on bacterial growth. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, D.I.; Oranskaya, M.N.; Lobyshev, V.I. Specificity of bacterial response to variations of the isotopic composition of water. Biophysics 2003, 48, 636–640. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Zubarev, R.A. Isotopic resonance hypothesis: Experimental verification by Escherichia coli growth measurements. Sci. rep. 2015, 5, 9215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basov, A.; Drobotenko, M.; Svidlov, A.; Gerasimenko, E.; Malyshko, V.; Elkina, A.; Baryshev, M.; Dzhimak, S. Inequality in the Frequency of the Open States Occurrence Depends on Single 2H/1H Replacement in DNA. Molecules 2020, 25, 3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khristich, A.N.; Mirkin, S.M. On the Wrong DNA Track: Molecular Mechanisms of Repeat-Mediated Genome Instability. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 4134–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Zhou, Q.A. Polyglutamine (PolyQ) Diseases: Navigating the Landscape of Neurodegeneration. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 2665–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.G.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.B. Mechanisms of Protein Toxicity in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3159–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.C.; Ho, L.I.; Chi, C.S.; Chen, S.J.; Peng, G.S.; Chan, T.M.; Lin, S.Z.; Harn, H.J. Polyglutamine (PolyQ) Diseases: Genetics to Treatments. Cell Transplant. 2014, 23, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyas, C.A.; La Spada, A.R. The CAG—Polyglutamine Repeat Diseases: A Clinical, Molecular, Genetic, and Pathophysiologic Nosology. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 147, pp. 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirali, T.; Serafini, M.; Cargnin, S.; Genazzani, A.A. Applications of Deuterium in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5276–5297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korchinsky, N.; Davis, A.M.; Boros, L.G. Nutritional Deuterium Depletion and Health: A Scoping Review. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, C. First Deuterated Drug Approved. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Base | A | T | G | C |

| 7.61 | 4.86 | 8.22 | 4.11 | |

| Å | 5.80 | 4.80 | 5.70 | 4.70 |

| , N·m | 2.35 | 1.61 | 2.27 | 1.54 |

| 6.20 | 6.20 | 9.60 | 9.60 | |

| 4.25 | 2.91 | 4.10 | 2.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorohova, A.; Velázquez-Pérez, L.; Drobotenko, M.; Lyasota, O.; Hernandez-Caceres, J.L.; Rodriguez-Labrada, R.; Svidlov, A.; Leontyeva, O.; Nechipurenko, Y.; Dzhimak, S. Isotopic H/D Exchange in Hydrogen Bonds Between the Nitrogenous Bases of the CAG Repeat Tract Makes It Possible to Stabilize Its Expansion in the ATXN2 Gene. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112708

Dorohova A, Velázquez-Pérez L, Drobotenko M, Lyasota O, Hernandez-Caceres JL, Rodriguez-Labrada R, Svidlov A, Leontyeva O, Nechipurenko Y, Dzhimak S. Isotopic H/D Exchange in Hydrogen Bonds Between the Nitrogenous Bases of the CAG Repeat Tract Makes It Possible to Stabilize Its Expansion in the ATXN2 Gene. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112708

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorohova, Anna, Luis Velázquez-Pérez, Mikhail Drobotenko, Oksana Lyasota, Jose Luis Hernandez-Caceres, Roberto Rodriguez-Labrada, Alexandr Svidlov, Olga Leontyeva, Yury Nechipurenko, and Stepan Dzhimak. 2025. "Isotopic H/D Exchange in Hydrogen Bonds Between the Nitrogenous Bases of the CAG Repeat Tract Makes It Possible to Stabilize Its Expansion in the ATXN2 Gene" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112708

APA StyleDorohova, A., Velázquez-Pérez, L., Drobotenko, M., Lyasota, O., Hernandez-Caceres, J. L., Rodriguez-Labrada, R., Svidlov, A., Leontyeva, O., Nechipurenko, Y., & Dzhimak, S. (2025). Isotopic H/D Exchange in Hydrogen Bonds Between the Nitrogenous Bases of the CAG Repeat Tract Makes It Possible to Stabilize Its Expansion in the ATXN2 Gene. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2708. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112708