WTAP Suppresses Cutaneous Melanoma Progression by Upregulation of KLF9: Insights into m6A-Mediated Epitranscriptomic Regulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gene Expression Data

2.2. Selection of m6A Genes

2.3. Differential Analysis

2.4. Survival Analysis

2.5. Immunohistochemical Staining

2.6. Cell Culture and Transfection

2.7. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

2.8. Quantification of mRNA m6A Methylation by MeRIP-qPCR

2.9. Western Blotting

2.10. Cell Viability Assay

2.11. Cell Scratch Assay

2.12. Weighted Gene Correlation Network Analysis and LASSO Regression Analysis

2.13. Correlation Analysis

2.14. WTAP Targets Online Prediction

2.15. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differential Expression of m6A Genes in Cutaneous Melanoma

3.2. Survival Analysis of m6A Genes in Cutaneous Melanoma

3.3. Verification of WTAP Downregulation and Investigation of Its Association with Melanoma Cells Properties

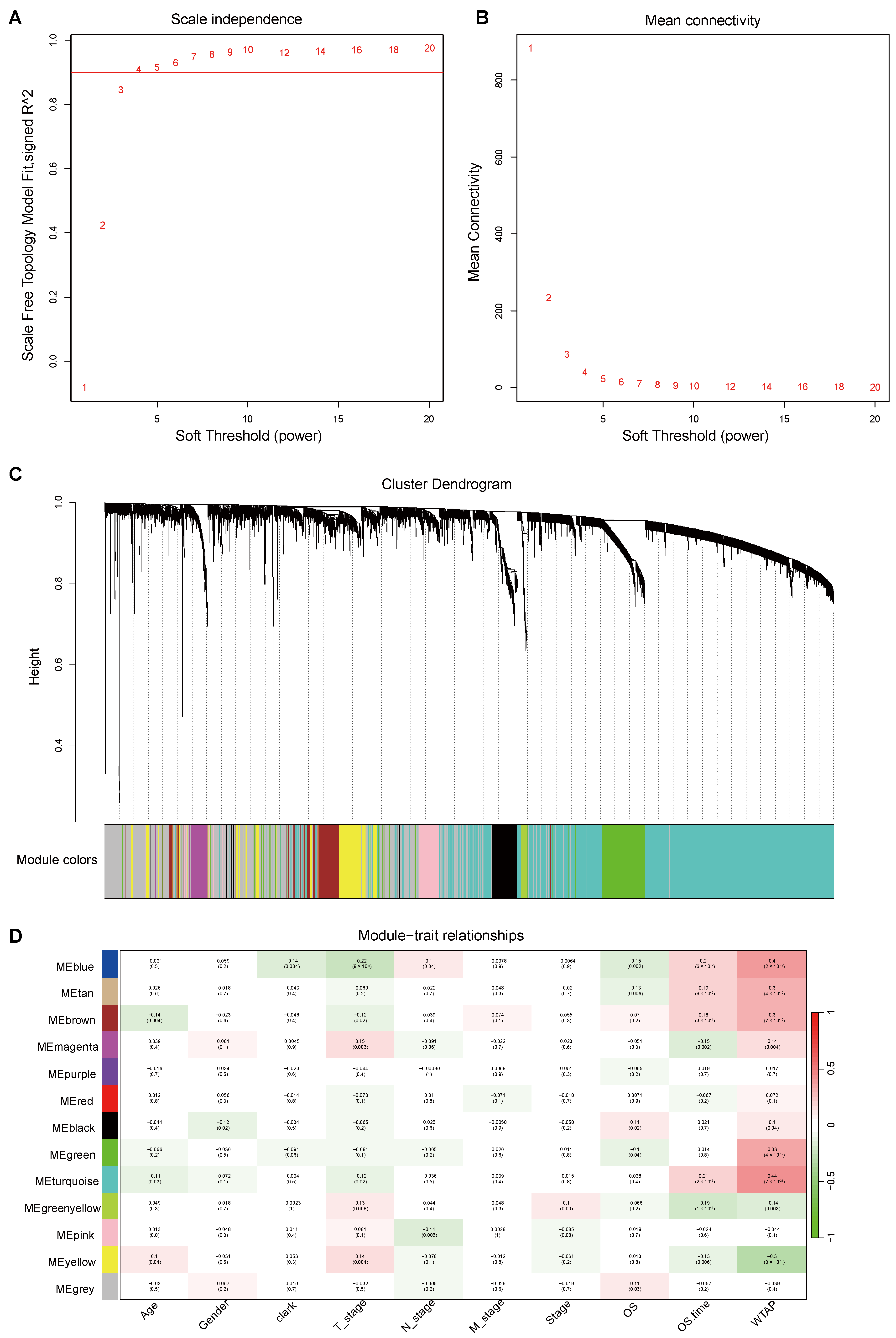

3.4. Correlation Between Modules and Phenotypes in WGCNA

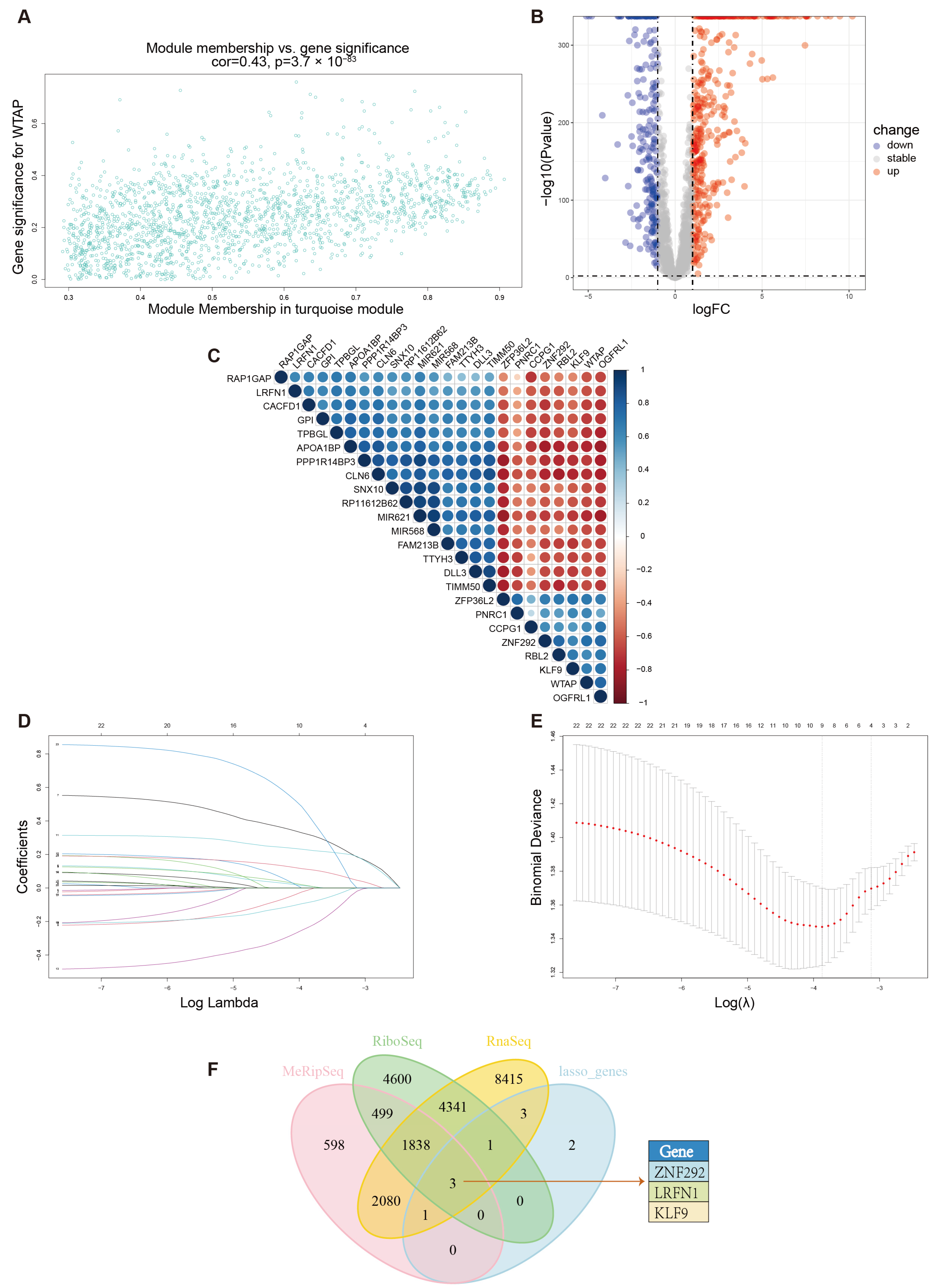

3.5. Differential Analysis and Survival Analysis of Module Genes and Selection of Potential Target of WTAP

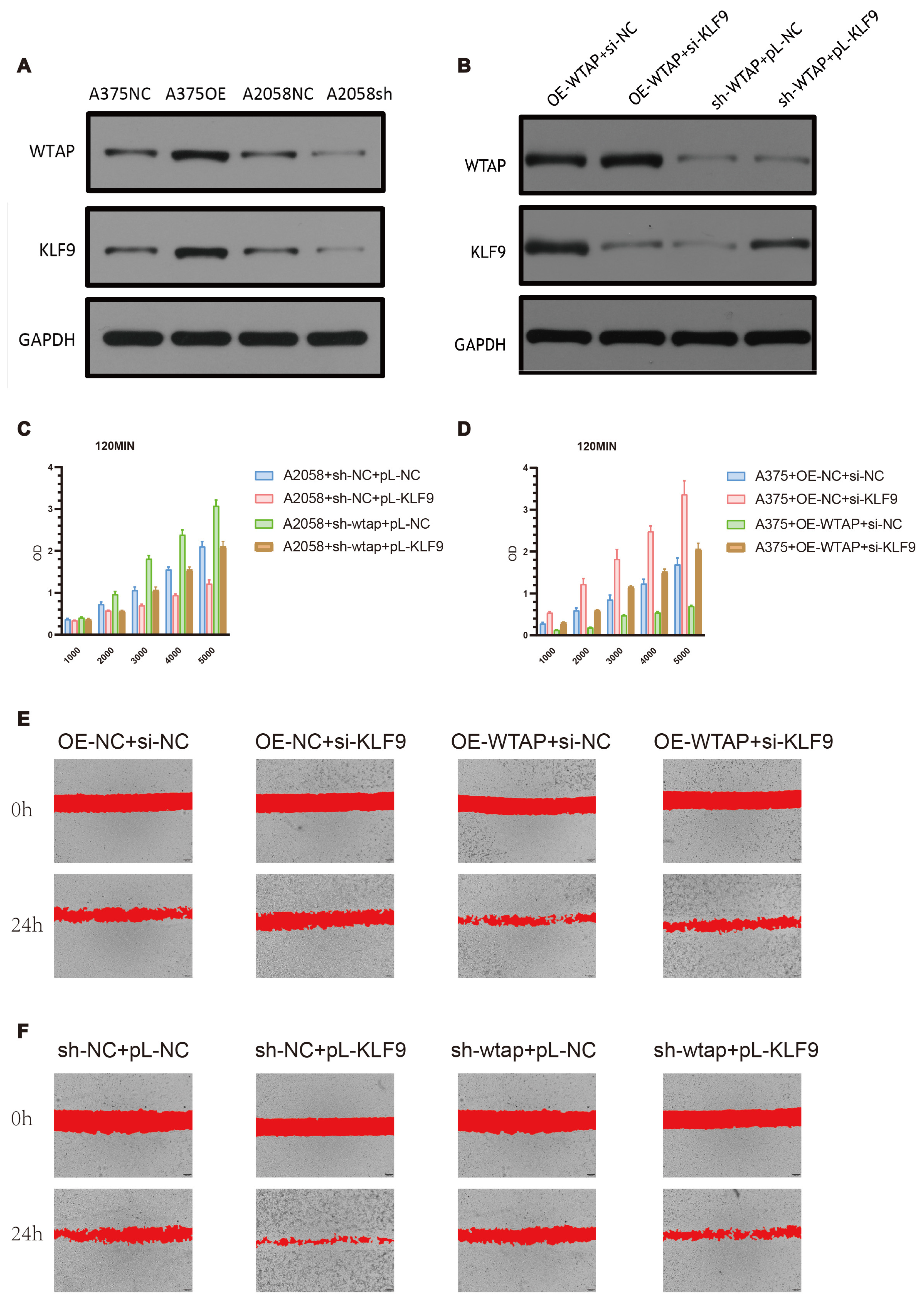

3.6. WTAP Regulates Cell Proliferation and Migration in Melanoma Cells Through KLF9

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WTAP | Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein |

| KLF9 | Krueppel-like factor 9 |

| m6A | N6-methyladenosine |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| GTEx | Genotype-Tissue Expression |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| AOD | Average optical density |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| CCK-8 | Cell counting kit-8 |

| WGCNA | Weighted gene correlation network analysis |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Dimitriou, F.; Krattinger, R.; Ramelyte, E.; Barysch, M.J.; Micaletto, S.; Dummer, R.; Goldinger, S.M. The World of Melanoma: Epidemiologic, Genetic, and Anatomic Differences of Melanoma Across the Globe. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastrelli, M.; Tropea, S.; Rossi, C.R.; Alaibac, M. Melanoma: Epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, diagnosis and classification. Vivo 2014, 28, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme, N.; Berx, G. From neural crest cells to melanocytes: Cellular plasticity during development and beyond. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2019, 76, 1919–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apalla, Z.; Lallas, A.; Sotiriou, E.; Lazaridou, E.; Ioannides, D. Epidemiological trends in skin cancer. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2017, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, S.; Tsao, H. Recognition, Staging, and Management of Melanoma. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 105, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Melanoma of the Skin. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program; National Cancer Institute: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2025.

- Yue, Y.; Liu, J.; He, C. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Gregory, R.I. RNAmod: An integrated system for the annotation of mRNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W548–W555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.; Yu, B.; Li, A.; Wu, H. Epigenetic Regulations in Autoimmunity and Cancer: From Basic Science to Translational Medicine. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, e2048980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Mei, W.; Qu, C.; Lu, J.; Shang, L.; Cao, F.; Li, F. Role of m6A writers, erasers and readers in cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, B.; Nie, Z.; Duan, L.; Xiong, Q.; Jin, Z.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y. The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petri, B.J.; Klinge, C.M. m6A readers, writers, erasers, and the m6A epitranscriptome in breast cancer. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2023, 70, e220110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokar, J.A.; Rath-Shambaugh, M.E.; Ludwiczak, R.; Narayan, P.; Rottman, F. Characterization and partial purification of mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase from HeLa cell nuclei. Internal mRNA methylation requires a multisubunit complex. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 17697–17704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Shi, H.; Ye, P.; Li, L.; Qu, Q.; Sun, G.; Sun, G.; Lu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Yang, C.G.; et al. m(6)A RNA Methylation Regulates the Self-Renewal and Tumorigenesis of Glioblastoma Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2622–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, H.; Huang, H.; Wu, H.; Qin, X.; Zhao, B.S.; Dong, L.; Shi, H.; Skibbe, J.; Shen, C.; Hu, C.; et al. METTL14 Inhibits Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Differentiation and Promotes Leukemogenesis via mRNA m(6)A Modification. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 191–205.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Su, R.; Sheng, Y.; Dong, L.; Dong, Z.; Xu, H.; Ni, T.; Zhang, Z.S.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; et al. Small-Molecule Targeting of Oncogenic FTO Demethylase in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 677-691.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, B.; Liu, Y.; Gao, Z.; Xu, J.; Yan, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J. Senescent neutrophils-derived exosomal piRNA-17560 promotes chemoresistance and EMT of breast cancer via FTO-mediated m6A demethylation. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Bai, Z.L.; Xia, D.; Zhao, Z.J.; Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhe, H. FTO regulates the chemo-radiotherapy resistance of cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) by targeting β-catenin through mRNA demethylation. Mol. Carcinog. 2018, 57, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.J.; Shim, H.E.; Han, M.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.S.; Baek, S.; Choi, K.U.; Hur, G.Y.; Oh, S.O. WTAP regulates migration and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma cells. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 48, 1271–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L. WTAP-Involved the m6A Modification of lncRNA FAM83H-AS1 Accelerates the Development of Gastric Cancer. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023, 66, 1883–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Lou, J.; Yan, P.; Kang, X.; Li, P.; Huang, Z. WTAP Contributes to the Tumorigenesis of Osteosarcoma via Modulating ALB in an m6A-Dependent Manner. Environ. Toxicol. 2023, 38, 1455–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Fan, Y.; Yan, C.; Jiamaliding, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Huang, M.; Ju, G.; Wu, J.; Peng, C. Comprehensive analysis about prognostic and immunological role of WTAP in pan-cancer. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1007696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, H.; Frohm-Nilsson, M.; Järås, J.; Kanter-Lewensohn, L.; Kjellman, P.; Månsson-Brahme, E.; Vassilaki, I.; Hansson, J. Prognostic factors in localized invasive primary cutaneous malignant melanoma: Results of a large population-based study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, R.; Agarwala, S.S.; Messersmith, H.; Alluri, K.C.; Ascierto, P.A.; Atkins, M.B.; Bollin, K.; Chacon, M.; Davis, N.; Faries, M.B.; et al. Systemic Therapy for Melanoma: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4794–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wei, J.; Cui, Y.H.; Park, G.; Shah, P.; Deng, Y.; Aplin, A.E.; Lu, Z.; Hwang, S.; He, C.; et al. m(6)A mRNA demethylase FTO regulates melanoma tumorigenicity and response to anti-PD-1 blockade. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Yin, J.; Yang, H.; Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Liu, L.; Zhong, J. ALKBH5-mediated m(6)A demethylation of FOXM1 mRNA promotes progression of uveal melanoma. Aging 2021, 13, 4045–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, S.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, P.; Qi, S.; Xie, J. ALKBH5 facilitates the progression of skin cutaneous melanoma via mediating ABCA1 demethylation and modulating autophagy in an m(6)A-dependent manner. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 1729–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chai, P.; Xie, M.; Ge, S.; Ruan, J.; Fan, X.; Jia, R. Histone lactylation drives oncogenesis by facilitating m(6)A reader protein YTHDF2 expression in ocular melanoma. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.Z.; Xiong, J.S.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.C.; Kong, Y.Q.; Miao, Q.J.; Tian, C.C.; Li, R.; Liu, J.Q.; et al. N6-methyladenosine reader YTHDF3 regulates melanoma metastasis via its ‘executor’ LOXL3. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; He, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, B.; Jia, R.; Chai, P.; Li, F.; Yang, Y.; Ge, S.; Jia, R.; et al. The m(6)A reading protein YTHDF3 potentiates tumorigenicity of cancer stem-like cells in ocular melanoma through facilitating CTNNB1 translation. Oncogene 2022, 41, 1281–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Bai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Peng, Q. N(6)-Methyladenosine regulator RBM15B acts as an independent prognostic biomarker and its clinical significance in uveal melanoma. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 918522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, P.Y.; Kim, G.; Poudel, M.; Lim, S.C.; Choi, H.S. METTL3 induces PLX4032 resistance in melanoma by promoting m(6)A-dependent EGFR translation. Cancer Lett. 2021, 522, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; Lin, Y.Y.; Bai, L.N.; Zhu, W. miR-302a-3p suppresses melanoma cell progression via targeting METTL3. J. Chemother. 2022, 34, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, B.; Rong, G.; Hou, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Du, D.; Li, Y. METTL3 Promotes the Growth and Invasion of Melanoma Cells by Regulating the lncRNA SNHG3/miR-330-5p Axis. Cell Transplant. 2023, 32, 9636897231188300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahal, U.; Le, K.; Gupta, M. RNA m6A methyltransferase METTL3 regulates invasiveness of melanoma cells by matrix metallopeptidase 2. Melanoma Res. 2019, 29, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Xu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, F.; Hu, D.N.; et al. RNA m(6) A methylation regulates uveal melanoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by targeting c-Met. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 7107–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, H.; Jia, D.; Li, T.; Xia, L. METTL3-induced UCK2 m(6)A hypermethylation promotes melanoma cancer cell metastasis via the WNT/β-catenin pathway. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Cao, M.; Hong, A.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Q.; Fang, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. m(6)A Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes the Progression of Primary Acral Melanoma via Mediating TXNDC5 Methylation. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 770325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Piao, C.; Ning, H. METTL14 promotes migration and invasion of choroidal melanoma by targeting RUNX2 mRNA via m6A modification. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2022, 26, 5602–5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, A.; Gu, X.; Ge, T.; Wang, S.; Ge, S.; Chai, P.; Jia, R.; Fan, X. Targeting histone deacetylase suppresses tumor growth through eliciting METTL14-modified m(6) A RNA methylation in ocular melanoma. Cancer Commun. 2023, 43, 1185–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.Y.; Wang, T.; Su, X.; Guo, S. Identification of the m(6)A RNA Methylation Regulators WTAP as a Novel Prognostic Biomarker and Genomic Alterations in Cutaneous Melanoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 665222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Jia, Q.; Zhong, L.; Hu, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Development and validation of an m6A RNA methylation regulator-based signature for the prediction of prognosis and immunotherapy in cutaneous melanoma. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 2641–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, C.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Yang, B.; He, B.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Dai, L.; et al. WTAP facilitates progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent epigenetic silencing of ETS1. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, K.; Umetani, M.; Minami, T.; Okayama, H.; Takada, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Aburatani, H.; Reid, P.C.; Housman, D.E.; Hamakubo, T.; et al. Wilms’ tumor 1-associating protein regulates G2/M transition through stabilization of cyclin A2 mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 17278–17283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, A.; Tuersunniyazi, A.; Meng, X.; Pei, Y.; Ji, W.; Feng, Z.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Kasimu, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. N6-methyladenosine RNA methylation regulator-related alternative splicing gene signature as prognostic predictor and in immune microenvironment characterization of patients with low-grade glioma. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 872186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, K.; Ozkan, A.I. The kruppel-like factor (KLF) family, diseases, and physiological events. Gene 2024, 895, 148027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetreault, M.P.; Yang, Y.; Katz, J.P. Krüppel-like factors in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, M.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Guo, D.; Gu, T.; Wang, B.; Xiao, L.; et al. KLF9 suppresses gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis through transcriptional inhibition of MMP28. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2019, 33, 7915–7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Song, P.; Zhao, Y.; An, N.; Xia, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, H.; Ge, J. miR-600 promotes ovarian cancer cells stemness, proliferation and metastasis via targeting KLF9. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Cao, X.; Sun, L.; Qian, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, X.; Shi, G.; Wang, D. KLF9 suppresses cell growth and induces apoptosis via the AR pathway in androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2021, 28, 101151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagati, A.; Moparthy, S.; Fink, E.E.; Bianchi-Smiraglia, A.; Yun, D.H.; Kolesnikova, M.; Udartseva, O.O.; Wolff, D.W.; Roll, M.V.; Lipchick, B.C.; et al. KLF9-dependent ROS regulate melanoma progression in stage-specific manner. Oncogene 2019, 38, 3585–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altonsy, M.O.; Song-Zhao, G.X.; Mostafa, M.M.; Mydlarski, P.R. Overexpression of Krüppel-Like Factor 9 Enhances the Antitumor Properties of Paclitaxel in Malignant Melanoma-Derived Cell Lines. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Wei, J.; He, C. Where, When, and How: Context-Dependent Functions of m6A Modification in mRNA Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Zhang, Y.; Mella, J.; He, C. m6A Readers Regulate mRNA Fate in Cancer. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 499–519. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, H.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, J. WTAP Suppresses Cutaneous Melanoma Progression by Upregulation of KLF9: Insights into m6A-Mediated Epitranscriptomic Regulation. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112685

Huang H, Li D, Li Y, Wang Y, Yin J. WTAP Suppresses Cutaneous Melanoma Progression by Upregulation of KLF9: Insights into m6A-Mediated Epitranscriptomic Regulation. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112685

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Huayu, Dong Li, Yichuan Li, Ying Wang, and Jin Yin. 2025. "WTAP Suppresses Cutaneous Melanoma Progression by Upregulation of KLF9: Insights into m6A-Mediated Epitranscriptomic Regulation" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112685

APA StyleHuang, H., Li, D., Li, Y., Wang, Y., & Yin, J. (2025). WTAP Suppresses Cutaneous Melanoma Progression by Upregulation of KLF9: Insights into m6A-Mediated Epitranscriptomic Regulation. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112685