Thyrotoxicosis and the Heart: An Underrecognized Trigger of Acute Coronary Syndromes

Abstract

1. Introduction

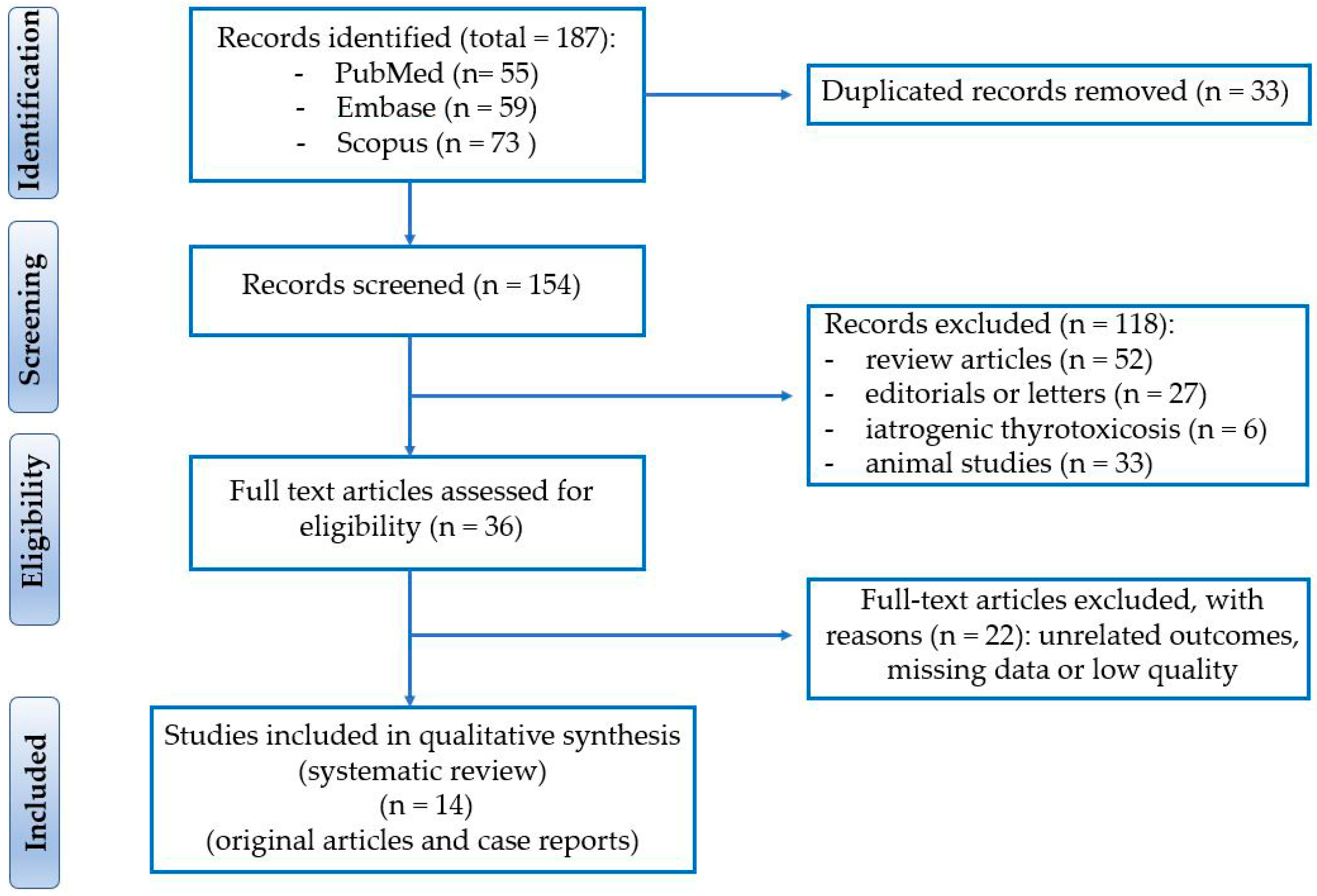

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Clinical Presentation

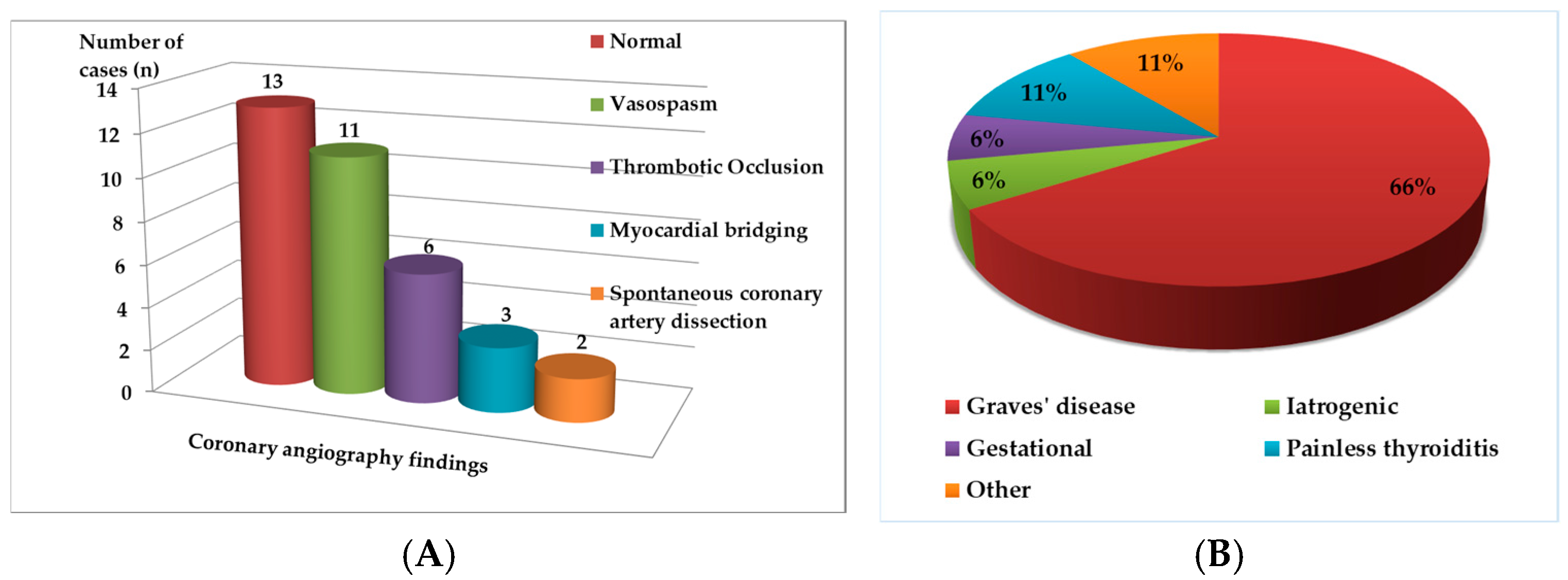

3.3. Coronary Angiography Findings

3.4. Thyroid Profile and Etiology

3.5. Outcomes

4. Discussion

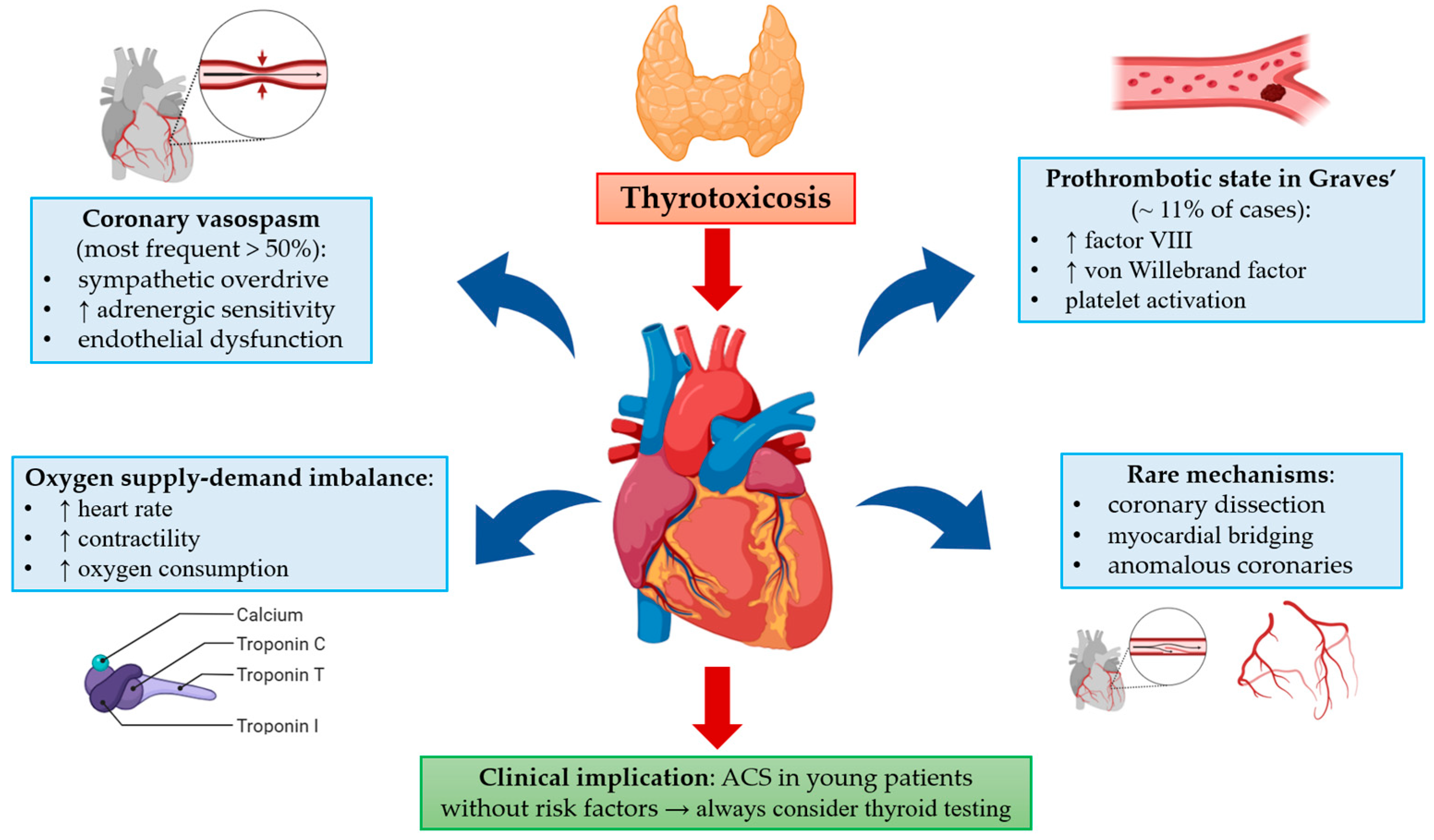

4.1. Pathophysiological Mechanisms

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Prognosis and Outcomes

4.4. Knowledge Gaps and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Acute coronary syndrome |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| AMI | Acute myocardial infarction |

| AST | Acute suppurative thyroiditis |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| F | Female |

| FT3 | Free triiodothyronine |

| FT4 | Free thyroxine |

| hCG | Human chorionic gonadotropin |

| HTN | Hypertension |

| ICD | Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator |

| LAD | Left anterior descending coronary artery |

| LBBB | Left bundle branch block |

| LCX | Left circumflex coronary artery |

| LM | Left main coronary artery |

| M | Male |

| MINOCA | Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries |

| NA | Not available/not reported |

| NSTEMI | Non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| PCI | Percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PTCA | Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty |

| RBBB | Right bundle branch block |

| RCA | Right coronary artery |

| SAT | Subacute thyroiditis |

| STEMI | ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction |

| TRs | Thyroid hormone receptors |

| TSH | Thyroid-stimulating hormone |

References

- Pingitore, A.; Mastorci, F.; Lazzeri, M.F.L.; Vassalle, C. Thyroid and heart: A fatal pathophysiological attraction in a controversial clinical liaison. Endocrines 2023, 4, 722–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, R.; Unar, A.; Jafar, T.H.; Chanihoon, G.Q.; Mubeen, B. A role of thyroid hormones in acute myocardial infarction: An update. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2023, 19, e280422204209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardehali, A.; Sooch, A.; Kiess, M.; Aymong, E.; Blanke, P.; Ferkh, A.; Grewal, J. Severe coronary vasospasm complicated by thyrotoxicosis in early pregnancy. JACC Case Rep. 2025, 30, 103621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibawa, K.; Wiyono, L.D.; Dewangga, R.; Sumarna, A.; Syamsuri, W.; Ariffudin, Y.; Suhendiwijaya, S.; Syah, P.A. When the heart deceives: A case report of hyperthyroidism disguised as STEMI in a female pregnant patient. Egypt. Heart J. 2025, 77, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, F.; Naderi, N.; Mousavinezhad, S.M.; Zadeh, A.Z. Unexpected Graves’-induced acute myocardial infarction in a young female, a literature review based on a case report. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 17, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širvys, A.; Baranauskas, A.; Budrys, P. A rare encounter: Unstable vasospastic angina induced by thyrotoxicosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.M.A.; Knott, K.; Saba, M.M.; Lim, P.O. Cardiac arrest in myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery (MINOCA) secondary to thyroid dysfunction. BMJ Case Rep. 2023, 16, e253500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, R.; Virk, H.U.H.; Goyfman, M.; Lee, A.; John, G. Thyrotoxicosis-related left main coronary artery spasm presenting as acute coronary syndrome. Cureus 2022, 14, e26408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Kaliyappan, A.; Kaushik, A.; Roy, A. Impending myocardial ischaemia during thyroid storm diagnosed through Wellens’ syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e250488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscoli, S.; Lecis, D.; Prandi, F.R.; Ylli, D.; Chiocchi, M.; Cammalleri, V.; Lauro, D.; Andreadi, A. Risk of sudden cardiac death in a case of spontaneous coronary artery dissection presenting with thyroid storm. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 3712–3717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dixey, M.; Barnes, A.; Fadhlillah, F. Graves’-induced prothrombotic state and the risk of early-onset myocardial infarction. BMJ Case Rep. 2021, 14, e243446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataallah, B.; Buttar, B.; Kaell, A.; Kulina, G.; Kulina, R. Coronary vasospasm-induced myocardial infarction: An uncommon presentation of unrecognized hyperthyroidism. J. Med. Cases 2020, 11, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Cham, M.D.; Huang, G.S. Storm and STEMI: A case report of unexpected cardiac complications of thyrotoxicosis. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2020, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klomp, M.; Siegelaar, S.E.; van de Hoef, T.P.; Beijk, M.A.M. A case report of myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease: Graves’ disease-induced coronary artery vasospasm. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2020, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, G.D.; Yahaya, N.; Yahya, M. Hyperthyroidism presenting as ST elevation myocardial infarction with normal coronaries—A case report. J. ASEAN Fed. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 34, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, F.; Yu, X.; Hu, S.; Shao, S. A silent myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries associated with Graves’ disease. Heart Lung 2019, 48, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.H.; Chang, W.C.; Su, C.S.; Liu, T.J.; Lee, W.L.; Lai, C.H. Vasospastic myocardial infarction complicated with ventricular tachycardia in a patient with hyperthyroidism. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 234, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, F.; Orsini, E.; Delle Donne, M.G.; Dini, F.L.; Marzilli, M. ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction associated with hyperthyroidism: Beware of coronary spasm! J. Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 18, 798–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rymer De Marchena, I.; Gutman, A.; Zaidan, J.; Yacoub, H.; Hoyek, W. Thyrotoxicosis mimicking ST elevation myocardial infarction. Cureus 2017, 9, e1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitjian, V.; Moazez, C.; Saririan, M.; August, D.L.; Roy, R. Manifestation of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction due to hyperthyroidism in an anomalous right coronary artery. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2017, 10, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannaka, V.B.; Lvovsky, D. A rare case of gestational thyrotoxicosis as a cause of acute myocardial infarction. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2016, 2016, 16–0063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Qu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Q. Severe hyperthyroidism presenting with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2015, 2015, 901214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.P.; Shen, B.T.; Dai, Y.M.; Zhao, X.Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, W. Acute myocardial infarction associated with painless thyroiditis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 348, 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouabdallaoui, N.; Mouquet, F.; Ennezat, P.V. Acute myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries associated with subclinical Graves’ disease. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 31, 1721.e1–1721.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.J.; Pattison, D.A.; Teo, E.P.; Price, S.; Gurvitch, R. Amiodarone-induced destructive thyroiditis associated with coronary artery vasospasm and recurrent ventricular fibrillation. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2013, 2, 65–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Patanè, S.; Marte, F.; Sturiale, M. Acute myocardial infarction without significant coronary stenoses associated with endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 156, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.P.; Lee, W.L.; Lai, H.C.; Ting, C.T.; Wang, K.Y.; Liu, T.J. Recurrent vasodilator-refractory acute coronary syndrome as the exclusive manifestation of Graves’ disease. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 30, 1656.e5–1656.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hama, M.; Abe, M.; Kawaguchi, T.; Ishida, Y.; Nosaka, M.; Kuninaka, Y.; Kimura, A.; Kondo, T. A case of myocardial infarction in a young female with subclinical hyperthyroidism. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 158, e23–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Jung, T.S.; Hahm, J.R.; Hwang, S.J.; Lee, S.M.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, S.K.; Chung, S.I. Thyrotoxicosis-induced acute myocardial infarction due to painless thyroiditis. Thyroid 2011, 21, 1149–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.H.; Zhang, S.Y. Hyperthyroidism-associated coronary spasm: A case of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction with thyrotoxicosis. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2011, 8, 258–259. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Patanè, S.; Marte, F. Atrial fibrillation and acute myocardial infarction without significant coronary stenoses associated with subclinical hyperthyroidism and erythrocytosis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2010, 145, e36–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patanè, S.; Marte, F.; Patanè, F.; Bella, G.D.; Chiofalo, S.; Cinnirella, G.; Evola, R. Acute myocardial infarction in a young patient with myocardial bridge and elevated levels of free triiodothyronine. Int. J. Cardiol. 2009, 132, 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, S.; Marte, F.; Bella, G.D.; Turiano, G. Acute myocardial infarction and subclinical hyperthyroidism without significant coronary stenoses. Int. J. Cardiol. 2009, 134, e135–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.; Peterson, G.; Rohatgi, A.; Ghayee, H.K.; Keeley, E.C.; Auchus, R.J.; Chang, A.Y. Hyperthyroidism-associated coronary vasospasm with myocardial infarction and subsequent euthyroid angina. Thyroid 2008, 18, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudleigh, R.A.; Davies, J.S. Graves’ thyrotoxicosis and coronary artery spasm. Postgrad. Med. J. 2007, 83, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, S.Y.; Liu, L.L.; Sun, J. Painless thyroiditis-induced acute myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 33, 983.e5–983.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.Y.; Genecin, A.; Greene, H.L.; Achuff, S.C. Coronary spasm with ventricular fibrillation during thyrotoxicosis: Response to attaining euthyroid state. Am. J. Cardiol. 1979, 43, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, W.A.; Prior, D.L.; Thamilarasan, M.; Grimm, R.A.; Asher, C.R. Graves’ disease and coronary artery spasm: Case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2010, 339, 185–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pingitore, A.; Chen, Y.; Gerdes, A.M.; Iervasi, G. Acute myocardial infarction and thyroid function: New pathophysiological and therapeutic perspectives. Ann. Med. 2012, 44, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razvi, S.; Jabbar, A.; Pingitore, A.; Danzi, S.; Biondi, B.; Klein, I.; Peeters, R.; Zaman, A.; Iervasi, G. Thyroid hormones and cardiovascular function and diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1781–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toschetti, T.; Parenti, C.; Ricci, I.; Addati, I.; Diona, S.; Esposito, S.; Street, M.E. Acute suppurative and subacute thyroiditis: From diagnosis to management. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case | Age (Years), Sex | ECG | Coronary Angiography | History of CV Disease | TSH Level (µIU/mL) | Free T4 Level (pmol/L) | Thyroid Storm | Hyperthyroidism Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardehali et al., 2025 [3] | 36, F, pregnant | ST-segment depression V3 to V6 | LM persistent spasm (90% stenosis) | No | Undetectable | 48.3 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Wibawa et al., 2025 [4] | 30, F, pregnant | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF, V4 to V6 | Normal | No | <0.05 | 34.9 | No | Gestational hyperthyroidism |

| Naderi et al., 2024 [5] | 36, F | Sinus tachycardia | Normal | No | 0.005 | 83.78 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Širvys et al., 2024 [6] | 62, F | ST-segment depression I, aVL, V4 to V6, ST-segment elevation aVR | Diffuse vasospasm in all coronary arteries | No | Undetectable | 40.19 | No | Not mentioned |

| Omar et al., 2023 [7] | 30, M | ST-segment elevation I, aVL, V1 to V5 | RCA spasm | No | <0.02 | 99.5 | Yes | Graves’ disease |

| Anjum et al., 2022 [8] | 47, F | Normal | LM spasm | HTN | 0.01 | 32.2 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Patra et al., 2022 [9] | Mid-50s, M | Biphasic T wave inversion in V2, V3 (Wellens) | 80% stenosis LAD (PTCA) | No | 0.020 | 1162.3 | Yes | Graves’ disease |

| Muscoli et al., 2022 [10] | 45, F | ST-segment elevation anterior leads, VF episodes | Spontaneous LAD dissection | No | 0.01 | 28.2 | Yes | Chronic Autoimmune Thyroid Disease |

| Dixey et al., 2021 [11] | 25, F | RBBB, Q waves V1 to V5, VF | LAD thrombotic occlusion, LAD dissection | No | <0.01 | 490.4 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Ataallah et al., 2020 [12] | 47, F | T wave inversion V1, V2, ST-segment depression V4, V5 | Severe vasospasm with mild non-obstructive coronary artery disease | No | 0.01 | 71.3 | No | Graves |

| Brown et al., 2020 [13] | 23, M | QT prolongation (QTc 652 ms) and minimal ST-segment elevations in V1–V4 | Normal CT coronary angiography | No | Undetectable | 41.2 | Yes | Graves’ disease |

| Klomp M. et al., 2020 [14] | 49, F | ST-segment depression II, III, aVF, V4 to V6 | LM and RCA spasm | No | <0.001 | 59.9 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Krishnan et al., 2019 [15] | 31, M | ST-segment elevation V2 to V4 | Normal | No | <0.005 | 66 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Li et al., 2019 [16] | 37, M | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF, V2 to V4 with Q waves II, III, aVF | Normal | No | 0.011 | 0.92 | Yes | Graves’ disease |

| Chang et al., 2017 [17] | 48, F | ST-segment elevation V1 to V3, VT | LAD, LCX, RCA spasm | No | 0.013 | 35.3 | No | Not mentioned |

| Menichetti et al., 2017 [18] | 58, F | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF | RCA spasm | 2-month history of rest angina | Undetectable | 17.0 | Yes | Graves’ disease |

| Rymer de Marchena et al., 2017 [19] | 54, M | ST-segment elevation II, III | Normal | No | <0.01 | 100.5 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Zeitjian et al., 2017 [20] | 51, F | Normal | Anomalous RCA origin | No | <0.015 | NA | No | Secondary to hypothyroidism treatment |

| Nannaka et al., 2016 [21] | 27, F, pregnant | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF | RCA spasm | <0.07 | 318.45 | Gestational (hCG induced) hyperthyroidism | ||

| Zhou et al., 2015 [22] | 66, F | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF, V2 to V6 | Normal | Cerebral infarction | <0.005 | >100 | No | Not mentioned |

| Zhang et al., 2014 [23] | 26, M | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF | Myocardial bridging over LAD | No | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | No | Painless thyroiditis |

| Bouabdallaoui et al., 2013 [24] | 23, F | Diffuse ST-segment elevation | Distal LAD thrombosis | No | <0.005 | NA | No | Graves’ disease |

| Brooks et al., 2013 [25] | 55, M | LBBB and 2 episodes of VF (ICD interrogation) | Atherosclerotic plaque with minor stenosis and spasm of distal LCX | ICD | <0.01 | 75.1 | No | Amiodarone-induced destructive thyroiditis |

| Patane et al., 2012 [26] | 75, F | Negative T wave II, III, avF, V1 to V6 | Normal | AF, HTN | 0.003 | 35.6 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Lee et al., 2012 [27] | 48, F | ST-segment elevation V1 to V3 | Normal | No | 0.031 | 334.6 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Hama et al., 2012 [28] | 25, F | Normal | LAD thrombosis (autopsy) | No | 0.03 | 24.3 | No | Subclinical hyperthyroidism |

| Kim et al., 2011 [29] | 35, M | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF | Normal | No | 0.04 | 58.1 | No | Painless thyroiditis |

| Kuang et al., 2011 [30] | 39, F | Widespread ST-segment depression | LM and RCA spasm | No | Undetectable | 49.7 | No | Not mentioned |

| Patane et al., 2010 [31] | 63, M | AF, negative T waves V4, V5 | Normal | No | 0.082 | 15.4 | No | Not mentioned |

| Patane et al., 2009 [32] | 28, M | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF | Myocardial bridging over LAD | No | 0.008 | NA | No | Iatrogenic hyperthyroidism |

| Patane et al., 2009 [33] | 67, F | New onset AF | Normal | Chest pain | 0.009 | 18.0 | No | Subclinical hyperthyroidism |

| Patel et al., 2008 [34] | 40, F | T wave inversion in precordial leads | LM and RCA spasm | No | <0.1 | 47.6 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Chudleigh et al., 2007 [35] | 36, F | Anterior Q waves, lateral ST depression with T wave inversion | LM stenosis | No | <0.02 | 120 | No | Graves’ disease |

| Chudleigh et al., 2007 [35] | 59, F | Inferior ST segment elevation | Normal | No | <0.02 | 46.2 | No | Not mentioned |

| Zheng et al., 2015 [36] | 21, M | ST-segment elevation II, III, aVF, V7 to V9 | Normal | No | 0.034 | 434.1 | No | Painless thyroiditis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anghel, L.; Diaconu, A.; Benchea, L.-C.; Prisacariu, C.; Scripcariu, D.V.; Zanfirescu, R.-L.; Bîrgoan, G.-S.; Sascău, R.A.; Stătescu, C. Thyrotoxicosis and the Heart: An Underrecognized Trigger of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112591

Anghel L, Diaconu A, Benchea L-C, Prisacariu C, Scripcariu DV, Zanfirescu R-L, Bîrgoan G-S, Sascău RA, Stătescu C. Thyrotoxicosis and the Heart: An Underrecognized Trigger of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112591

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnghel, Larisa, Anca Diaconu, Laura-Cătălina Benchea, Cristina Prisacariu, Dragoș Viorel Scripcariu, Răzvan-Liviu Zanfirescu, Gavril-Silviu Bîrgoan, Radu Andy Sascău, and Cristian Stătescu. 2025. "Thyrotoxicosis and the Heart: An Underrecognized Trigger of Acute Coronary Syndromes" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112591

APA StyleAnghel, L., Diaconu, A., Benchea, L.-C., Prisacariu, C., Scripcariu, D. V., Zanfirescu, R.-L., Bîrgoan, G.-S., Sascău, R. A., & Stătescu, C. (2025). Thyrotoxicosis and the Heart: An Underrecognized Trigger of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2591. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112591