Insights into the Natural and Treatment Courses of Hepatitis B in Children: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

- Individuals aged between 0 and 18 years at the time of their first pediatric consultation for chronic HBV infection.

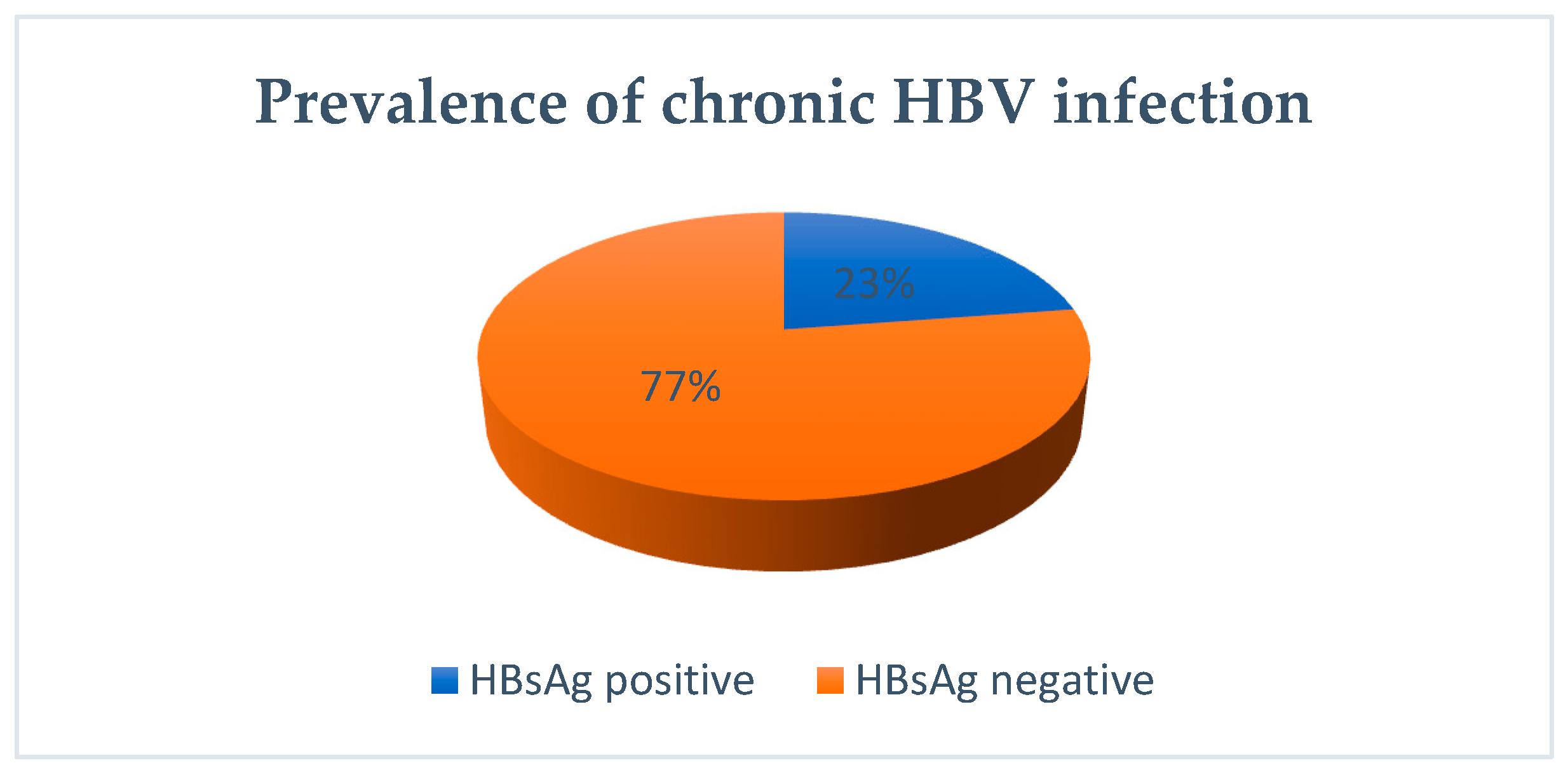

- Detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) persisting for a minimum of six months.

3. Results

3.1. Natural Evolution

3.2. Evolution under Treatment

4. Discussion

4.1. Vertical Transmission

4.2. Clinical Manifestations

4.3. Spontaneous Seroconversion in HBe System

4.4. Antiviral Treatment

4.5. Treatment Side Effects

4.6. Correlations between HBe Seroconversion and Parasitosis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hepatitis B. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Global Hepatitis Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565455 (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Indolfi, G.; Easterbrook, P.; Dusheiko, G.; Siberry, G.; Chang, M.-H.; Thorne, C.; Bulterys, M.; Chan, P.-L.; El-Sayed, M.H.; Giaquinto, C.; et al. Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Children and Adolescents. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokal, E.M.; Paganelli, M.; Wirth, S.; Socha, P.; Vajro, P.; Lacaille, F.; Kelly, D.; Mieli-Vergani, G.; European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Management of Chronic Hepatitis B in Childhood: ESPGHAN Clinical Practice Guidelines: Consensus of an Expert Panel on Behalf of the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 814–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, A.; Tabernero, D.; Buti, M.; Rodriguez-Frias, F. Hepatitis B Virus: The Challenge of an Ancient Virus with Multiple Faces and a Remarkable Replication Strategy. Antivir. Res. 2018, 158, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.; Harmanci, H.; Hutin, Y.; Hess, S.; Bulterys, M.; Peck, R.; Rewari, B.; Mozalevskis, A.; Shibeshi, M.; Mumba, M.; et al. Global Progress on the Elimination of Viral Hepatitis as a Major Public Health Threat: An Analysis of WHO Member State Responses 2017. JHEP Rep. 2019, 1, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.-M.; Choi, J.; Lim, Y.-S. Chapter 7—Hepatitis B: Epidemiology, Natural History, and Diagnosis. In Comprehensive Guide to Hepatitis Advances; Seto, W.-K., Eslam, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 183–203. ISBN 9780323983686. [Google Scholar]

- Paganelli, M.; Stephenne, X.; Sokal, E.M. Chronic Hepatitis B in Children and Adolescents. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stinco, M.; Rubino, C.; Trapani, S.; Indolfi, G. Treatment of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Children and Adolescents. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 6053–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K.N.; Lai, F.M. Clinical Features and the Natural Course of Hepatitis B Virus-Related Glomerulopathy in Adults. Kidney Int. Suppl. 1991, 35, S40–S45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Inui, A.; Fujisawa, T. Pediatric Hepatitis B Treatment. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, A.A.; Fine, M.; London, W.T. Spontaneous Seroconversion in Hepatitis B E Antigen-Positive Chronic Hepatitis B: Implications for Interferon Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 176, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Popalis, C.; Yeung, L.T.F.; Ling, S.C.; Ng, V.; Roberts, E.A. Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection in Children: 25 Years’ Experience. J. Viral. Hepat. 2013, 20, e20–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjørup, I.E.; Skinhøj, P. New Aspects on the Natural History of Chronic Hepatitis B Infection: Implication for Therapy. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 35, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.-C.; Kao, J.-H.; Chen, D.-S. Peginterferon α in the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2014, 14, 995–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-M.; Choe, B.-H.; Chu, M.A.; Cho, S.M. Comparison of lamivudine-induced HBsAg loss rate according to age in children with chronic hepatitis B. Korean J. Hepatol. 2009, 15, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Peng, X.; Chang, Y.; Hu, P.; Ren, H.; Xu, H. The Efficacy of Pegylated Interferon Alpha-2a and Entecavir in HBeAg-Positive Children and Adolescents with Chronic Hepatitis B. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komatsu, H.; Inui, A.; Yoshio, S.; Kanto, T.; Umetsu, S.; Tsunoda, T.; Fujisawa, T. High Dose of Pegylated Interferon for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B in Children Infected with Genotype C. JPGN Rep. 2020, 1, e005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karayiannis, P.; Thomas, H.C. Hepatitis B Virus: General Features. In Encyclopedia of Virology, 3rd ed.; Mahy, B.W.J., Van Regenmortel, M.H.V., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 350–360. ISBN 9780123744104. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, M.M.; Block, J.M.; Haber, B.A.; Karpen, S.J.; London, W.T.; Murray, K.F.; Narkewicz, M.R.; Rosenthal, P.; Schwarz, K.B.; McMahon, B.J.; et al. Treatment of Children with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: Patient Selection and Therapeutic Options. Hepatology 2010, 52, 2192–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Filippo Villa, D.; Navas, M.-C. Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus-An Update. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, R.R.; Eckmann, L. Treatment of Giardiasis: Current Status and Future Directions. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2014, 16, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurmatova, N.; Mirsalikhova, N.K.; Asilbekova, M.A.; Irsalieva, F.; Dustbabaeva, N.; Akhmedov, J.K. Body Sensitization to Various Antigens in Children with Chronic Hepatitis B and Concomitant Giardiasis. Russ. J. Immunol. 2020, 23, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| New EASL Nomenclature | Old Nomenclature | Viral Replication | Risk of HCC | ALT Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBeAg+ Chronic HBV Infection | Immunotolerant | High Replicative Phase | Low | Low |

| HBeAg+ Chronic Hepatitis B | Immuno-clearance/Active Immune Phase | Moderately Replicative Phase (HBeAg+/-) | Increased | High |

| HBeAg- Chronic HBV Infection | Inactive Carrier | Low Replicative Phase | Low | Low |

| HBeAg- Chronic Hepatitis HBV | Chronic Hepatitis HBeAg | Moderately Replicative Phase HBeAg- | Increased | High |

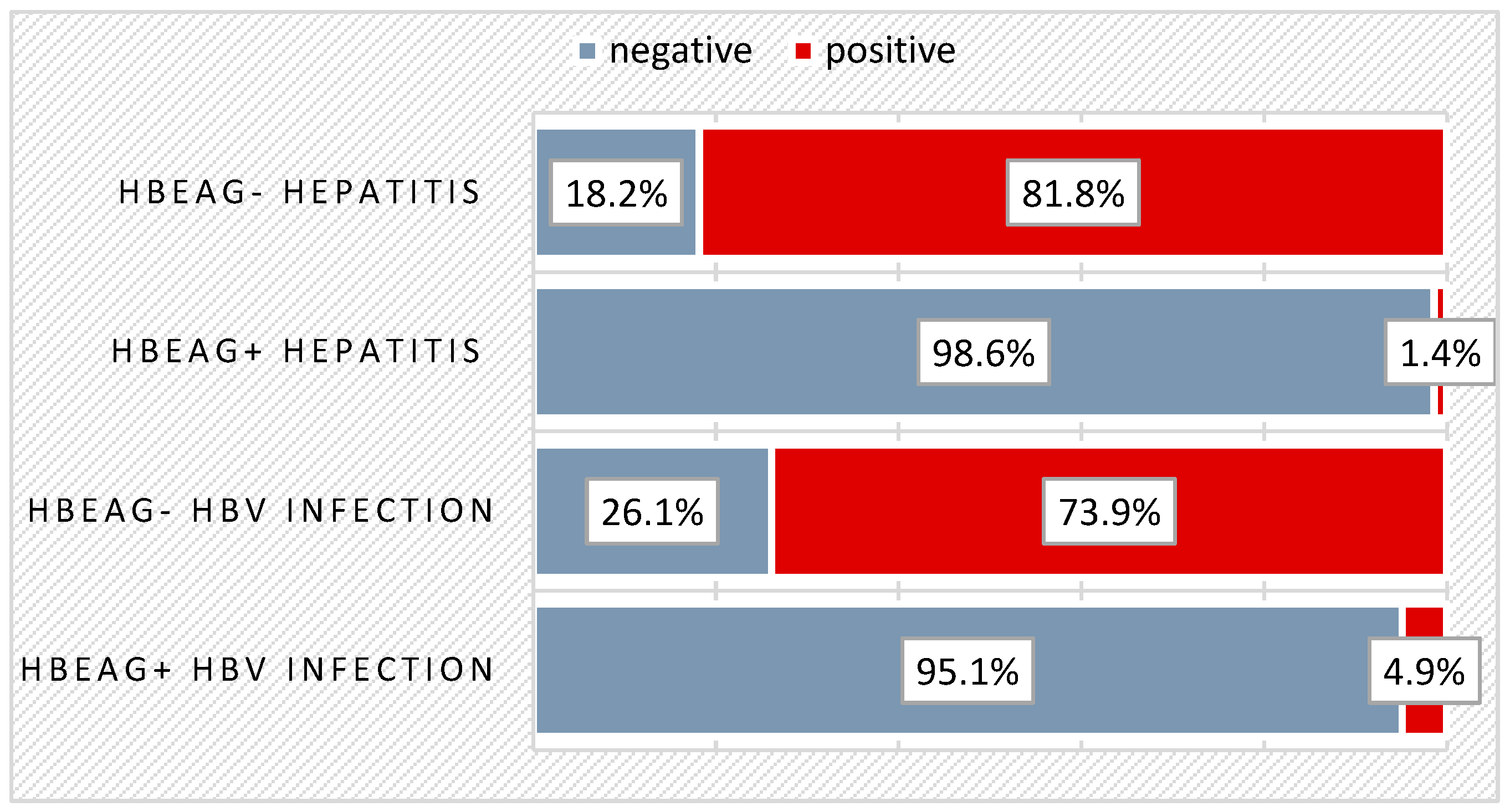

| Age Group (Years) | HBeAg- Hepatitis | HBeAg+ Hepatitis | HBeAg- Infection | HBeAg+ Infection | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square = 12,189/p = 0.007 ** | n% | n% | n% | n% | n% |

| 0–1 year | 2 (18.2%) | 19 (26.0%) | - | 9 (22.0%) | 30 (20.3%) |

| 2–5 years | 2 (18.2%) | 17 (23.3%) | 8 (34.8%) | 12 (29.3%) | 39 (26.4%) |

| 6–10 years | 3 (27.3%) | 14 (19.2%) | 6 (26.1%) | 11 (26.8%) | 34 (23.0%) |

| 11–14 years | 1 (9.1%) | 16 (21.9%) | 6 (26.1%) | 5 (12.2%) | 28 (18.9%) |

| 15–18 years | 3 (27.3%) | 7 (9.6%) | 3 (13.0%) | 4 (9.8%) | 17 (11.5%) |

| Total | 11 (100.0%) | 73 (100.0%) | 23 (100.0%) | 41 (100.0%) | 148 (100.0%) |

| Patients related to group (%) | 7.4% | 49.3% | 15.5% | 27.7% | 100% |

| Disease Stage at DG | HBeAg+ Infection | HBeAg- Infection | HBeAg+ Hepatitis | HBeAg- Hepatitis | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square = 12,189/p = 0.007 ** | n% | n% | n% | n% | n% |

| Clinical Manifestation NO | 23 (56.1%) | 11 (47.8%) | 18 (24.7%) | 4 (36.4%) | 56 (37.8%) |

| Clinical Manifestation YES | 18 (43.9%) | 12 (52.2%) | 55 (75.3%) | 7 (63.6%) | 92 (62.2%) |

| Total | 41 (100.0%) | 23 (100.0%) | 73 (100.0%) | 11 (100.0%) | 148 (100.0%) |

| Clinical Manifestations | HBeAg+ Infection n, % | HBeAg- Infection n, % | HBeAg+ Hepatitis n, % | HBeAg- Hepatitis n, % | Total n, % | Pearson Chi-Square/p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | - | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (5.5%) | - | 6 (4.1%) | 3.852/0.278 |

| Loss of appetite | 2 (4.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | 17 (23.3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 24 (16.2%) | 7.001/0.072 |

| Physical weakness | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (4.3%) | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (9.1%) | 6 (4.1%) | 3.197/0.362 |

| Semi consistent stools | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (4.3%) | 3 (4.1%) | 1 (9.1%) | 6 (4.1%) | 0.998/0.802 |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (7.3%) | 3 (13.0%) | 11 (15.1%) | 2 (18.2%) | 19 (12.8%) | 1.723/0.632 |

| Hepatomegaly | 1 (2.4%) | - | 15 (20.5%) | 2 (18.2%) | 18 (12.2%) | 11.991/0.007 ** |

| Odynophagia | 1 (2.4%) | - | 6 (8.2%) | 1 (9.1%) | 8 (5.4%) | 3.442/0.328 |

| Cough | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (8.7%) | 6 (8.2%) | 1 (9.1%) | 10 (6.8%) | 1.693/0.638 |

| Rhinorrhea/pharyngeal congestion | 4 (9.8%) | 1 (4.3%) | 4 (5.5%) | 1 (9.1%) | 10 (6.8%) | 1.081/0.782 |

| Epistaxis | 3 (7.3%) | - | 3 (4.1%) | - | 6 (4.1%) | 2.559/0.465 |

| Fever | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (4.3%) | 4 (5.5%) | - | 7 (4.7%) | 0.647/0.886 |

| Fatigue | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (2.7%) | - | 5 (3.4%) | 2.579/0.461 |

| Others | 5 (12.2%) | 4 (17.4%) | 14 (19.2%) | 3 (27.3%) | 26 (17.6%) | 1.664/0.645 |

| Age | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 5 months | 1 | 1.1 |

| 1, 2 years | 2 | 2.2 |

| 2 years | 8 | 9.0 |

| 3 years | 2 | 2.2 |

| 5 years | 1 | 1.1 |

| 6 years | 2 | 2.2 |

| 7 years | 4 | 4.5 |

| 8 years | 4 | 4.5 |

| 9 years | 2 | 2.2 |

| 10 years | 1 | 1.1 |

| 11 years | 1 | 1.1 |

| 12 years | 2 | 2.2 |

| 13 years | 4 | 4.5 |

| 14 years | 2 | 2.2 |

| 15 years | 7 | 7.9 |

| 16 years | 1 | 1.1 |

| HBe Spontaneous Seroconversion | Lamblia Pre- Seroconversion No (n, %) | Lamblia Pre- Seroconversion Yes (n, %) | Lamblia Pre- Seroconversion Unknown (n, %) | Total (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square = 1.791/p = 0.408 | ||||

| NO | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.3%) | - | 1 (2.3%) |

| YES | 7 (100%) | 15 (93.8%) | 21 (100%) | 43 (97.7%) |

| Total | 7 (100%) | 16 (100%) | 21 (100%) | 44 (100%) |

| Disease Stage at DG | Antiviral Treatment No (n, %) | Antiviral Treatment Yes (n, %) | Total (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Chi-Square = 9.456/p = 0.024 | |||

| HBeAg+ Infection | 29 (32.6%) | 12 (20.3%) | 41 (27.7%) |

| HBeAg- Infection | 16 (18.0%) | 7 (11.9%) | 23 (15.5%) |

| HBeAg+ Hepatitis | 35 (39.3%) | 38 (64.4%) | 73 (49.3%) |

| HBeAg- Hepatitis | 9 (10.1%) | 2 (3.4%) | 11 (7.4%) |

| Total | 89 (100%) | 59 (100%) | 148 (100%) |

| Antiviral Treatment | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Interferon | 20 | 13.5 |

| Peginterferon | 10 | 6.8 |

| Entecavir | 21 | 14.2 |

| Telbivudine | 1 | 0.7 |

| Tenofovir | 5 | 3.4 |

| Zeffix | 16 | 10.8 |

| Side Effects | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| No | 23 | 39% |

| Yes | 36 | 61% |

| Total | 59 | 100% |

| Clinical Manifestations | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | 17 | 28.8 |

| Leukopenia | 6 | 10.2 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5 | 8.5 |

| Loss of appetite | 4 | 6.8 |

| Osteopenia | 4 | 6.8 |

| Abdominal pain | 4 | 6.8 |

| Chills | 3 | 5.1 |

| Headache | 3 | 5.1 |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 3.4 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 2 | 3.4 |

| Psychomotor agitation | 2 | 3.4 |

| Arthralgia | 2 | 3.4 |

| Cardiovascular disorders | 2 | 3.4 |

| Epistaxis/gingival bleeding | 1 | 1.7 |

| Fracture | 1 | 1.7 |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 | 1.7 |

| Lymphopenia | 1 | 1.7 |

| Myalgia | 2 | 3.4 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 1 | 1.7 |

| Urticaria | 1 | 1.7 |

| Vertigo | 1 | 1.7 |

| HBe Seroconversion Post-Treatment | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| No | 33 | 55.9 |

| Yes | 26 | 44.1 |

| Total | 59 | 100 |

| Treatment | Intron A | PegIFN | Entecavir | Telbivudine | Tenofovir | Zeffix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBe seroconversion post-treatment | 50% | 60% | 28.8% | 100% | 20% | 68.8% |

| Nr patients | 10 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Forna, L.; Bozomitu, L.; Lupu, A.; Lupu, V.V.; Cojocariu, C.; Anton, C.; Girleanu, I.; Singeap, A.M.; Muzica, C.M.; Trifan, A. Insights into the Natural and Treatment Courses of Hepatitis B in Children: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12071585

Forna L, Bozomitu L, Lupu A, Lupu VV, Cojocariu C, Anton C, Girleanu I, Singeap AM, Muzica CM, Trifan A. Insights into the Natural and Treatment Courses of Hepatitis B in Children: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines. 2024; 12(7):1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12071585

Chicago/Turabian StyleForna, Lorenza, Laura Bozomitu, Ancuta Lupu, Vasile Valeriu Lupu, Camelia Cojocariu, Carmen Anton, Irina Girleanu, Ana Maria Singeap, Cristina Maria Muzica, and Anca Trifan. 2024. "Insights into the Natural and Treatment Courses of Hepatitis B in Children: A Retrospective Study" Biomedicines 12, no. 7: 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12071585

APA StyleForna, L., Bozomitu, L., Lupu, A., Lupu, V. V., Cojocariu, C., Anton, C., Girleanu, I., Singeap, A. M., Muzica, C. M., & Trifan, A. (2024). Insights into the Natural and Treatment Courses of Hepatitis B in Children: A Retrospective Study. Biomedicines, 12(7), 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12071585