Impact of Portal Vein Resection (PVR) in Patients Who Underwent Curative Intended Pancreatic Head Resection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Data

3.2. Histopathological Work-Up and Patients’ Outcome

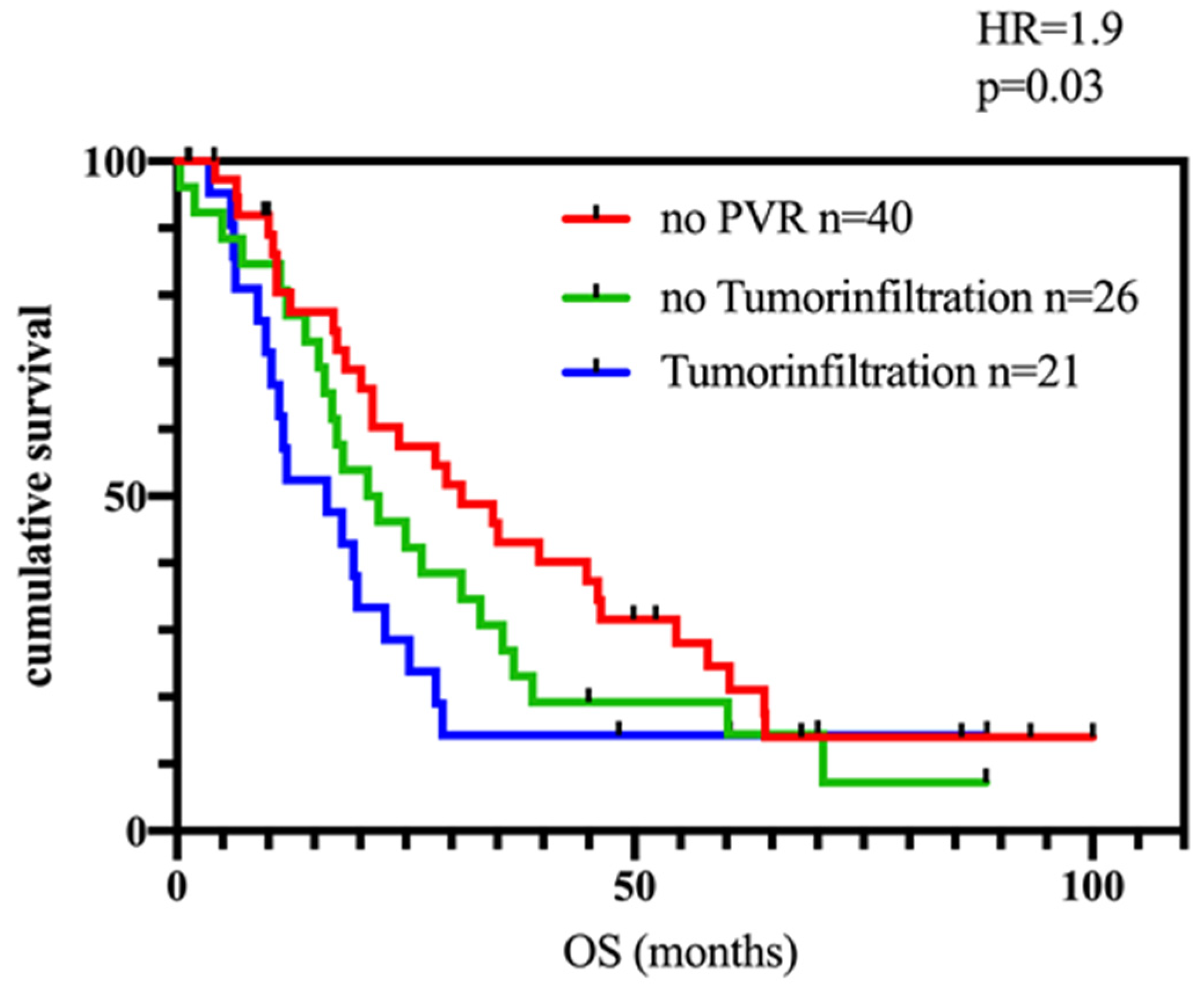

3.3. PVR and Patients’ Outcome

3.4. Impact of Tumor Infiltration of the Portal Vein

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murakami, Y.; Satoi, S.; Motoi, F.; Sho, M.; Kawai, M.; Matsumoto, I.; Honda, G. Multicentre Study Group of Pancreatobiliary, S. Portal or superior mesenteric vein resection in pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic head carcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimptsch, U.; Krautz, C.; Weber, G.F.; Mansky, T.; Grützmann, R. Nationwide In-hospital Mortality Following Pancreatic Surgery in Germany is Higher than Anticipated. Ann. Surg. 2016, 264, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, A.; Liu, F.; Wu, L.; Si, X.; Zhou, Y. Histopathologic tumor invasion of superior mesenteric vein/ portal vein is a poor prognostic indicator in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 32600–32607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kang, T.W.; Cha, D.I.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.H.; Jang, K.T.; Han, I.W.; Sohn, I. Prediction and clinical implications of portal vein/superior mesenteric vein invasion in patients with resected pancreatic head cancer: The significance of preoperative CT parameters. Clin. Radiol. 2018, 73, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshimoto, S.; Hishinuma, S.; Shirakawa, H.; Tomikawa, M.; Ozawa, I.; Wakamatsu, S.; Hoshi, S.; Hoshi, N.; Hirabayashi, K.; Ogata, Y. Reassessment of the clinical significance of portal-superior mesenteric vein invasion in borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 43, 1068–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, T.T.; Poon, R.T.; Chok, K.S.; Chan, A.C.; Tsang, S.H.; Dai, W.C.; Chan, S.C.; Fan, S.T.; Lo, C.M. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular reconstruction for adenocarcinoma of the pancreas with borderline resectability. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 17448–17455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapshyn, H.; Bronsert, P.; Bolm, L.; Werner, M.; Hopt, U.T.; Makowiec, F.; Wittel, U.A.; Keck, T.; Wellner, U.F.; Bausch, D. Prognostic factors after pancreatoduodenectomy with en bloc portal venous resection for pancreatic cancer. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2016, 401, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.S.; Park, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, S.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, S.A.; Woo, S.M.; Lee, W.J.; Hong, E.K. Clinical significance of portal-superior mesenteric vein resection in pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic head cancer. Pancreas 2012, 41, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, S.; Oussoultzoglou, E.; Bachellier, P.; Rosso, E.; Nakano, H.; Audet, M.; Jaeck, D. Significance of the depth of portal vein wall invasion after curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Arch. Surg. 2007, 142, 172–179, discussion 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagohri, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Konishi, M.; Inoue, K.; Takahashi, S. Survival benefits of portal vein resection for pancreatic cancer. Am. J. Surg. 2003, 186, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, J.F.; Raut, C.P.; Lee, J.E.; Pisters, P.W.; Vauthey, J.N.; Abdalla, E.K.; Gomez, H.F.; Sun, C.C.; Crane, C.H.; Wolff, R.A.; et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection: Margin status and survival duration. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2004, 8, 935–949, discussion 949–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dusch, N.; Oldani, M.; Steffen, T.; Kitz, J.; Koenig, U.; Azizian, A.; Konig, A.; Strobel, P.; Beissbarth, T.; Ghadimi, M.; et al. Intensified Histopathological Work-Up after Pancreatic Head Resection Reveals Relevant Prognostic Markers. Digestion 2021, 102, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockhorn, M.; Uzunoglu, F.G.; Adham, M.; Imrie, C.; Milicevic, M.; Sandberg, A.A.; Asbun, H.J.; Bassi, C.; Buchler, M.; Charnley, R.M.; et al. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: A consensus statement by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery 2014, 155, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, R.; Sabin, C.; Abu Hilal, M.; Al-Hilli, A.; Aroori, S.; Bond-Smith, G.; Bramhall, S.; Coldham, C.; Hammond, J.; Hutchins, R.; et al. Impact of portal vein infiltration and type of venous reconstruction in surgery for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Ito, H.; Ono, Y.; Matsueda, K.; Mise, Y.; Ishizawa, T.; Inoue, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Hiratsuka, M.; Unno, T.; et al. Impact of portal vein resection with splenic vein reconstruction after pancreatoduodenectomy on sinistral portal hypertension: Who needs reconstruction? Surgery 2019, 165, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, Y.; Matsueda, K.; Koga, R.; Takahashi, Y.; Arita, J.; Takahashi, M.; Inoue, Y.; Unno, T.; Saiura, A. Sinistral portal hypertension after pancreaticoduodenectomy with splenic vein ligation. Br. J. Surg. 2015, 102, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, I.D.; Bhalla, S.; Sanchez, L.A.; Fields, R.C.; Hawkins, W.G.; Strasberg, S.M. Pattern of Venous Collateral Development after Splenic Vein Occlusion in an Extended Whipple Procedure (Whipple at the Splenic Artery) and Long-Term Results. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2017, 21, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Demir, I.E.; Schorn, S.; Jager, C.; Scheufele, F.; Friess, H.; Ceyhan, G.O. Venous resection during pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer: A systematic review. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Xiong, J.; Zhou, F.; Tao, J.; Liu, T.; Zhao, G.; Gou, S. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection for local advanced pancreatic head cancer: A single center retrospective study. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2008, 12, 2183–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.P.; Psarelli, E.E.; Jackson, R.; Ghaneh, P.; Halloran, C.M.; Palmer, D.H.; Campbell, F.; Valle, J.W.; Faluyi, O.; O’Reilly, D.A.; et al. Patterns of Recurrence After Resection of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Secondary Analysis of the ESPAC-4 Randomized Adjuvant Chemotherapy Trial. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpero, J.R.; Sauvanet, A. Vascular Resection for Pancreatic Cancer: 2019 French Recommendations Based on a Literature Review From 2008 to 6-2019. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, A.; Ito, H.; Ono, Y.; Sato, T.; Mise, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Saiura, A. Regional pancreatoduodenectomy versus standard pancreatoduodenectomy with portal vein resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with portal vein invasion. BJS Open 2020, 4, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, A.; Harada, A.; Nonami, T.; Kaneko, T.; Inoue, S.; Takagi, H. Clinical significance of portal invasion by pancreatic head carcinoma. Surgery 1995, 117, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalski, C.W.; Kong, B.; Jäger, C.; Kloe, S.; Beier, B.; Braren, R.; Esposito, I.; Erkan, M.; Friess, H.; Kleeff, J. Outcomes of resections for pancreatic adenocarcinoma with suspected venous involvement: A single center experience. BMC Surg. 2015, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasawa, M.; Mise, Y.; Yoshioka, R.; Oba, A.; Ono, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Imamura, H.; Hiromichi, I.; Takahashi, Y.; Kawasaki, S.; et al. Preoperative Decision to Perform Portal Vein Resection Improves Survival in Patients with Resectable Pancreatic Head Cancer Adjacent to Portal Vein. Ann. Surg. Open 2021, 2, e064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, X.; Kou, J.; Ma, J.; Li, L.; Fan, H.; Lang, R.; He, Q. Proposed Chaoyang vascular classification for superior mesenteric-portal vein invasion, resection, and reconstruction in patients with pancreatic head cancer during pancreaticoduodenectomy—A retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2018, 53, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.V.; Michiels, N.; van Roessel, S.; Besselink, M.G.; Bosscha, K.; Busch, O.R.; van Dam, R.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; Koerkamp, B.G.; van der Harst, E.; et al. Venous wedge and segment resection during pancreatoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer: Impact on short- and long-term outcomes in a nationwide cohort analysis. Br. J. Surg. 2021, 109, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurihara, C.; Yoshimi, F.; Sasaki, K.; Nakao, K.; Lijima, T.; Kawasaki, H.; Nagai, H. Impact of portal vein invasion and resection length in pancreatoduodenectomy on the survival rate of pancreatic head cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2013, 60, 1759–1765. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneoka, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Isogai, M. Portal or superior mesenteric vein resection for pancreatic head adenocarcinoma: Prognostic value of the length of venous resection. Surgery 2009, 145, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleive, D.; Labori, K.J.; Line, P.D.; Gladhaug, I.P.; Verbeke, C.S. Pancreatoduodenectomy with venous resection for ductal adenocarcinoma rarely achieves complete (R0) resection. HPB 2020, 22, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, F.; Berresheim, F.; Felsenstein, M.; Malinka, T.; Pelzer, U.; Denecke, T.; Pratschke, J.; Bahra, M. Routine portal vein resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma shows no benefit in overall survival. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, D.; Takahashi, H.; Hama, N.; Toshiyama, R.; Asukai, K.; Hasegawa, S.; Wada, H.; Sakon, M.; Ishikawa, O. The clinical impact of splenic artery ligation on the occurrence of digestive varices after pancreaticoduodenectomy with combined portal vein resection: A retrospective study in two institutes. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasberg, S.M.; Bhalla, S.; Sanchez, L.A.; Linehan, D.C. Pattern of venous collateral development after splenic vein occlusion in an extended Whipple procedure: Comparison with collateral vein pattern in cases of sinistral portal hypertension. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2011, 15, 2070–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiihara, M.; Higuchi, R.; Izumo, W.; Yazawa, T.; Uemura, S.; Furukawa, T.; Yamamoto, M. Retrospective evaluation of risk factors of postoperative varices after pancreaticoduodenectomy with combined portal vein resection. Pancreatology 2020, 20, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Bai, X.; Li, Q.; Gao, S.; Lou, J.; Que, R.; Yadav, D.K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Liang, T. Role of Collateral Venous Circulation in Prevention of Sinistral Portal Hypertension After Superior Mesenteric-Portal Vein Confluence Resection during Pancreaticoduodenectomy: A Single-Center Experience. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 2054–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n = 90 | Percentage | PVR | non-PVR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of surgery | |||||

| PPPD | 76 | 84.4% | 41 (53.9%) | 35 (46.1%) | |

| Whipple | 6 | 6.7% | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | |

| TP | 8 | 8.9% | 6 (75%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Portal vein resection | 50 | 55.6% | |||

| Wedge Resection | 13 | 26% | |||

| Complete resection | 37 | 74% | |||

| Patients with surgical complications | 23 | 25.6% | |||

| POPF | 15 | 16.7% | 6 (40%) | 9 (60%) | |

| DGE | 7 | 7.8% | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

| Postoperative bleeding | 7 | 7.8% | 3 (42.9%) | 4 (57.1%) | |

| Leakage of bile duct anastomosis | 4 | 4.4% | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | |

| Neoadjuvant treated patients | 7 | 7.8% | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) | |

| Adjuvant treated patients | 63 | 70% | 34 (68%) | 29 (72.5%) | |

| FOLFIRINOX | 5 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Gemcitabine | 43 | 19 | 24 | ||

| Gemcitabine/Capecitabine | 11 | 8 | 3 | ||

| Gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Capecitabine | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| (y)pT-Stage | |||||

| T0 | 2 | 2.2% | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | |

| T1 | 4 | 4.5% | 1 (25%) | 3 (75%) | |

| T2 | 21 | 23.3% | 15 (71.4%) | 6 (28.6%) | |

| T3 | 63 | 70% | 34 (54%) | 29 (46%) | |

| T4 | 0 | 0% | - | - | |

| (y)pN-Stage | |||||

| N0 | 25 | 27.8% | 11 (44%) | 14 (56%) | |

| N1 | 56 | 62.2% | 32 (57.1%) | 24 (42.9%) | |

| N2 | 9 | 10% | 7 (77.8%) | 2 (22.2%) | |

| Grading | |||||

| G1 | 1 | 1.1% | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | |

| G2 | 65 | 72.2% | 39 (60%) | 26 (40%) | |

| G3 | 22 | 24.5% | 11 (50%) | 11 (50%) | |

| GX | 2 | 2.2% | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) | |

| Resection margin | |||||

| R0 | 58 | 64.4% | 28 (48.3%) | 30 (51.7%) | |

| CRM+ | 19 | 33.8% | 13 (68.4%) | 6 (31.6%) | |

| CRM− | 24 | 41.4% | 7 (29.2%) | 17 (70.8%) | |

| CRMx | 15 | 25.8% | 8 (53.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| R1 | 32 | 35.6% | 22 (68.8%) | 10 (31.1%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernhardt, M.; Rühlmann, F.; Azizian, A.; Kölling, M.A.; Beißbarth, T.; Grade, M.; König, A.O.; Ghadimi, M.; Gaedcke, J. Impact of Portal Vein Resection (PVR) in Patients Who Underwent Curative Intended Pancreatic Head Resection. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11113025

Bernhardt M, Rühlmann F, Azizian A, Kölling MA, Beißbarth T, Grade M, König AO, Ghadimi M, Gaedcke J. Impact of Portal Vein Resection (PVR) in Patients Who Underwent Curative Intended Pancreatic Head Resection. Biomedicines. 2023; 11(11):3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11113025

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernhardt, Markus, Felix Rühlmann, Azadeh Azizian, Max Alexander Kölling, Tim Beißbarth, Marian Grade, Alexander Otto König, Michael Ghadimi, and Jochen Gaedcke. 2023. "Impact of Portal Vein Resection (PVR) in Patients Who Underwent Curative Intended Pancreatic Head Resection" Biomedicines 11, no. 11: 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11113025

APA StyleBernhardt, M., Rühlmann, F., Azizian, A., Kölling, M. A., Beißbarth, T., Grade, M., König, A. O., Ghadimi, M., & Gaedcke, J. (2023). Impact of Portal Vein Resection (PVR) in Patients Who Underwent Curative Intended Pancreatic Head Resection. Biomedicines, 11(11), 3025. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11113025