Abstract

This umbrella review aimed to determine the various drugs used to treat trigeminal neuralgia (TN) and to evaluate their efficacies as well as side effects by surveying previously published reviews. An online search was conducted using PubMed, CRD, EBSCO, Web of Science, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library with no limits on publication date or patients’ gender, age, and ethnicity. Reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials pertaining to drug therapy for TN, and other relevant review articles added from their reference lists, were evaluated. Rapid reviews, reviews published in languages other than English, and reviews of laboratory studies, case reports, and series were excluded. A total of 588 articles were initially collected; 127 full-text articles were evaluated after removing the duplicates and screening the titles and abstracts, and 11 articles were finally included in this study. Except for carbamazepine, most of the drugs had been inadequately studied. Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine continue to be the first choice for medication for classical TN. Lamotrigine and baclofen can be regarded as second-line drugs to treat patients not responding to first-line medication or for patients having intolerable side effects from carbamazepine. Drug combinations using carbamazepine, baclofen, gabapentin, ropivacaine, tizanidine, and pimozide can yield satisfactory results and improve the tolerance to the treatment. Intravenous lidocaine can be used to treat acute exaggerations and botulinum toxin-A can be used in refractory cases. Proparacaine, dextromethorphan, and tocainide were reported to be inappropriate for treating TN. Anticonvulsants are successful in managing trigeminal neuralgia; nevertheless, there have been few studies with high levels of proof, making it challenging to compare or even combine their results in a statistically useful way. New research on other drugs, combination therapies, and newer formulations, such as vixotrigine, is awaited. There is conclusive evidence for the efficacy of pharmacological drugs in the treatment of TN.

1. Introduction

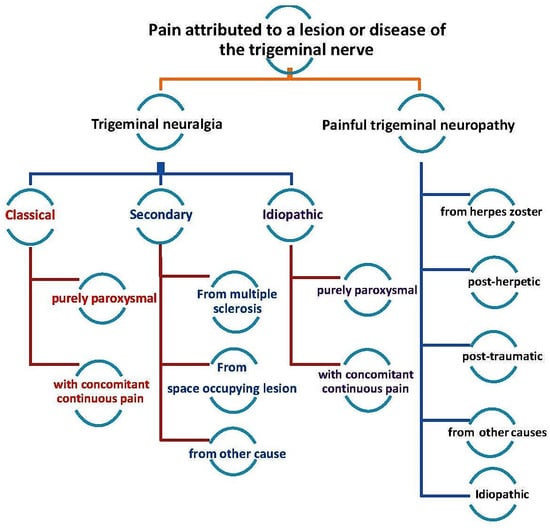

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN), also known as tic douloureux, is a disorder that affects the trigeminal nerve and is characterized by the presence of sudden, repetitive waves of pain that last from a few seconds to a few minutes [1]. The pain might be triggered by a sensory stimulus on the face, lips, or oral mucosa, or during certain functional movements of the face, and it is a debilitating chronic condition that occurs following injury or inflammation of the peripheral trigeminal nerve. As described in a recent review, peripheral and central nociceptive circuits are involved in neuropathic pain conditions that involve the trigeminal nerve (Bista and Imlach) [2]. TN is one of several disorders related to the trigeminal nerve [3] and is divided into three major types: classical, secondary, or idiopathic (Figure 1). The most common cause of TN, classical TN, is vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve at the root entry zone. Microvascular decompression (MVD) is the first-line treatment for classical TN. Secondary TN can be caused by tumors or vascular abnormalities in the posterior fossa, or it might be caused by multiple sclerosis. It is called idiopathic TN when no cause can be found [4,5]. The term paroxysm has been used to describe the sudden, unexpected, and short-lasting nature of the pain. However, some of TN patients experience concomitant continuous pain in the form of a dull ache in the same area as the paroxysmal pain [4]. Although the exact mechanism involved in the development of TN remains poorly understood, the potential mechanisms involve peripheral and central nociceptive circuit dysfunctions, which could lead to cross-excitation of an intact nerve by an injured nerve, neuro-glial interactions, alterations in the wirings within the CNS, loss of inhibitory control, disruptions in the functions of ion channels, and sensitization by inflammatory mediators (Bista and Imlach) [5].

Figure 1.

Classification of trigeminal nerve disorders, obtained from the study by Zhange et al., 2016 [3].

TN can impact the psychological, emotional, and socioeconomic well-being of a patient. The treatment of this condition is often challenging, and the majority of the therapies focus on symptomatic relief to lessen the intensity and incidence of pain [4]. The therapeutic modalities are based on pharmacological, interventional, and alternative medicine. Pharmaceutical management is minimally invasive, and antiepileptics have mainly been used as first-line treatment [5]. Carbamazepine has been used to treat various types of neuropathic pain since the early 1960s; however, the side effects associated with this drug are a significant cause for concern [6]. Subsequently, several antiepileptic and other types of drugs have been used to treat neuropathic pain, including TN (Table 1).

Table 1.

The medications available for neuropathic pain.

Several studies on the efficacies of the various treatment modalities for TN have been published; additionally, systematic reviews of these interventional studies are available in the literature (Table 1). More than 30 pharmacological interventions have been used to treat TN. However, they have not been comprehensively reviewed in most of the systematic reviews, except for a few that included two or more drugs [5,9,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. In 2019, the European Academy of Neurology published a survey of the developments in the diagnosis and treatment of TN and emphasized the necessity for further studies on the therapeutics for this condition [69]. Recent results indicate that TN behaves significantly differently than previously expected. The first reaction of patients treated with the various medication combinations was rather positive. Side effects were widespread with all the medicines, along with a reduced quality of life, which may lead to therapy discontinuation. However, drug resistance was uncommon, and fewer individuals required neurosurgery. This shows that the immediate response rate is higher than previously anticipated [44,59,66].

This is the first systematic review to methodically recognize, organize, classify, and summarize information about the efficacy of therapeutics for TN from several international review articles. This review aimed to identify and assess the available review articles, evaluate their quality, compile and compare their conclusions, and assess their merits for drawing the best evidence. The information from this review article can be used as an updated (2022-December) reference for health care providers and can contribute to evidence-based (empirical) decision making.

2. Methodology

This systematic review was performed and presented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2009 statement. The systematic review protocol was registered in the Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), University of York, with the registration number CRD42023408948. The PICOS (participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design) method was used to determine the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2).

Table 2.

PICOS statement for the study.

Inclusion criteria: Reviews and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving drug therapy for TN and other relevant reviews from articles included in their reference lists.

Exclusion criteria: Rapid reviews, reviews published in languages other than English, reviews of laboratory studies and uncontrolled trials, reviews of qualitative studies, and case reports/series.

Full-text screening: Full-text screening was conducted starting from the latest articles to the older ones. The drug(s) evaluated and the publication dates of the clinical trials included in each systematic review were noted. Reviews referring to the latest drug trials were included in our systematic review. Older articles were included only if they contained data that were not reported in the newer review articles. One or more systematic reviews were selected for each drug.

Search strategy and data collection process: Two independent reviewers conducted an online search, which was limited to reviews and meta-analyses published in the English language, regardless of the time of study and the gender, age, and ethnicity of the patients, using multiple databases (Table 3). The collection process ended on 1 December 2022.

Table 3.

The search strategy.

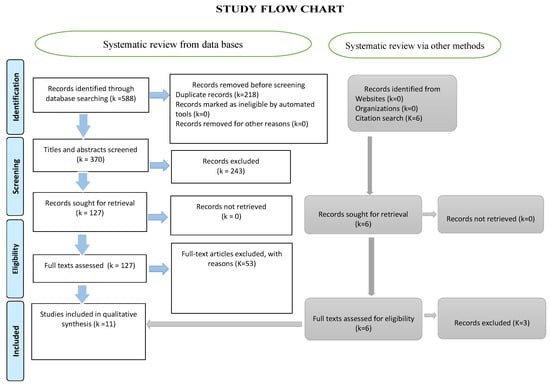

Data screening and retrieval: Two independent reviewers examined the segregated collection of titles and authors and excluded the duplicates. The titles and abstracts were evaluated and review articles were selected based on the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. The two independent selections of the two reviewers were matched, and discord was settled by a third reviewer. Only full-text articles were analyzed and the data were retrieved using a specially designed template (Figure 2). The elements included in the data retrieval form were as follows: intervention, control, authors, year of publication, reported level of evidence, the efficiency of intervention over control, adverse effects, study conclusions, and our comments.

Figure 2.

The PRISMA flow chart illustrating the various stages of the systematic review.

Data Synthesis

The full text of each article was reviewed and summaries were generated individually by two reviewers. The data were classified and the comments of each reviewer were added after verifying the reference cited in the included systematic review and the involved clinical trial. The synthesized data were discussed among all the reviewers and a consensus was reached.

3. Results

Out of the 588 titles initially selected, 370 were screened following the removal of duplicates. Subsequently, 127 full texts were thoroughly evaluated and 11 review articles were finally included in this study (Figure 2).

A total of 31 pharmacological interventions were evaluated. The articles were analyzed and the drugs were evaluated, and their efficacy, the level of evidence, the adverse effects, and the conclusions were summarized. Table 4 presents a compilation of the essential drugs used for the medical management of TN.

Table 4.

Data collected from the 11 articles included in this review.

3.1. Additional Information about the Drugs Included in the Review Articles

3.1.1. Carbamazepine and Oxcarbazepine

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine have been considered the first line of treatment for pain management [5,73]. The adverse effects of these two drugs are a cause for concern because they can affect the patient’s willingness to continue with the treatment. Oxcarbazepine has relatively fewer adverse effects than carbamazepine. Oxcarbazepine may be considered as the first-line medication for secondary TNs; however, patients with multiple sclerosis need to be monitored for the primary disease [5]. The significant side effects associated with carbamazepine necessitated a search for more efficacious and safe substitutes.

3.1.2. Eslicarbazepine

Eslicarbazepine acetate is a third-generation antiepileptic drug that belongs to the dibenzazepine family, along with carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. The most common side effects of this drug include dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness. There is insufficient evidence about the benefits of this drug. A retrospective and open-label study reported the effectiveness of eslicarbazepine (dose, 200–1200 mg/day) for TN. However, it can be considered for the treatment of neuropathic pain, headaches, and cranial neuralgia in TN patients who do not respond to or tolerate the first-line treatments.

3.1.3. Gabapentin

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comprising a total of 1331 patients reported a comparable efficacy of gabapentin with carbamazepine, with considerably fewer side effects [8]. Gabapentin might be considered a second-line drug and used as refractory therapy for patients with TN. It presented with a superior life satisfaction index B over carbamazepine and was associated with significantly fewer adverse effects [8]. Nonetheless, the efficacy of gabapentinoids for the treatment of TN has not been sufficiently evaluated.

3.1.4. Ropivacaine and Gabapentin

Ropivacaine is a long-acting amide local anesthetic. A single-blind, low-participant clinical trial evaluated the combined effect of ropivacaine (peripheral nerve block in the trigger zone) and gabapentin (oral administration) and reported that they induced analgesia and improved the quality of life of the patient [5,21,71]. Although ropivacaine alone demonstrated adequate analgesia, combination therapy with a low dose of gabapentin demonstrated superior overall results [71].

3.1.5. Ropivacaine and Carbamazepine

Similarly, the combination of ropivacaine and carbamazepine was found to reduce the side effects and limitations of carbamazepine [4].

3.1.6. Lamotrigine

Lamotrigine might be considered as a second-level drug for TN. The patient-reported adverse effects of lamotrigine (vertigo, nausea, visual impairment, and reduced neuromuscular control) are similar to those seen with carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. Furthermore, it is associated with a high incidence of dermatological reactions, which can be reduced by regulating the dosage [5]. Lamotrigine can be used to treat secondary TN; however, it can aggravate the symptoms of multiple sclerosis, in some instances. Nonetheless, the levels of evidence with regard to this drug are generally low [5].

3.1.7. Levetiracetam

Levetiracetam is an antiepileptic drug that is thought to act by targeting high-voltage, N-type calcium channels and the synaptic vesicle protein 2A, thereby hindering the conduction of impulses through the synapse. It has shown acceptable efficacy and tolerability in patients with TN [4]. Although reports suggest the efficacy of levetiracetam in TN, most of them were open-label, pilot, or short-term studies with inadequate numbers of participants and a dosage of about 3–4 g/day [4]. Hence, additional randomized and placebo-controlled trials are warranted to confirm its effects.

3.1.8. Phenytoin

Phenytoin is a well-known antiepileptic drug used to manage seizures and reduce anxiety. It has been used to treat TN and other types of neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in some instances. However, there is insufficient evidence to support its benefits in TN patients, and further qualitative randomized trials are required to confirm its effects.

3.1.9. Pregabalin

Pregabalin is an analog of gamma-aminobutyric acid type B (GABA) and structurally similar to gabapentin. It has been used to treat neuropathic pain in some cases, but there is little evidence of its benefits in patients with TN. The side effects of this drug are less marked than those of other antiepileptic drugs. The combination of pregabalin and carbamazepine was found to be effective in the case of refractory trigeminal neuralgia [4].

3.1.10. Topiramate

Topiramate is an antiepileptic used to treat seizures. A systematic review and meta-analysis [7] of all available randomized controlled trials indicated that the efficacy of topiramate was similar to that of carbamazepine, with acceptable patient tolerability. However, the studies included in the meta-analysis had low-grade evidence.

3.1.11. Proparacaine

A review reported that ophthalmic anesthetic proparacaine drops (0.5%) did not significantly improve the symptoms of TN when compared to the placebo, thus indicating that it might not produce long-lasting effects [70]. Hence, based on current evidence, the use of this drug for TN can be ruled out.

3.1.12. Dextromethorphan

The effect of the cough suppressant dextromethorphan was compared with that of lorazepam in one study [56]. However, it proved to be ineffective for the treatment of TN.

3.1.13. Tizanidine

Low-grade evidence from a double-blinded cross-over study comprising 11 participants indicated adequate analgesia following the use of tizanidine when compared to that using a placebo [59]. However, an insufficient number of participants attained complete analgesia; moreover, the efficacy was lost after a few months. The patient-reported side effects, such as dizziness, drowsiness, and tiredness were not significant [59]. In another study, the side effects associated with tizanidine were less than those observed with carbamazepine; however, the clinical efficacy of this drug was also lower than that of carbamazepine. Moreover, the sample size was small, and the highest doses used in the study were 18 mg for tizanidine and 900 mg for carbamazepine [5]. The inefficiency of tizanidine in providing relief could be attributed to its low influence on the neural reaction of low-threshold mechanoreceptors, which possibly plays an essential role in the pathophysiology of TN [64].

3.1.14. Pimozide

Pimozide is an antipsychotic drug and, in most studies, it appeared to be superior to carbamazepine in providing relief against noncompliant trigeminal neuralgia; however, the side effects, which included central nervous system disorders, hand shivers, and diminished cognition, were found to be significant [5]. Alternatively, Yang, F. et al. [60] reported that the effect of pimozide was inferior to the other seven drugs and placebo used for comparison in their study [60].

3.1.15. Tocainide

The palliative outcome of the antiarrhythmic agent tocainide was comparable to that of carbamazepine [56]. However, the common side effects of this drug, which included nausea, paresthesia, and dermatological reactions, limited its use for the treatment of TN.

3.1.16. Lidocaine

Lidocaine has been used in various forms: topical application (8%) in the oral mucosa; nasal spray; local infiltration in trigger zones; and intravenous infusion. The combination of lidocaine and ropivacaine, carbamazepine, or gabapentin has yielded better results than carbamazepine alone [60].

3.1.17. Baclofen

Baclofen might be effective against TN secondary to multiple sclerosis; it relieves the spasticity observed in patients with multiple sclerosis. However, it can cause momentary drowsiness and muscular hypotonia. Furthermore, a sudden withdrawal of the drug could instigate convulsions and delirium. In one study, levorotatory baclofen was found to be exponentially effective and demonstrated reduced side effects when compared to racemic baclofen [59]; however, the study comprised a limited number of participants for short-term therapy.

Low-grade evidence from a study on baclofen and carbamazepine reported that baclofen alone was slightly superior to carbamazepine alone; the combination of both these drugs, however, was significantly superior [59]. Although the aforementioned study was double-blinded and randomized, the results can only be considered as low-grade evidence due to the limited sample size and a participant dropout rate of 30% [59].

3.1.18. Sumatriptan

The subcutaneous injection of sumatriptan (3 mg) with oral administration (100 mg/day) yielded a significant improvement in analgesia in patients with TN and was sustained for a week after the termination of the treatment [70]. A random effects rankogram evaluation revealed that the effects of sumatriptan were superior to those of intranasal lidocaine, intravenous lidocaine, botulinum toxin, ophthalmic proparacaine, and a placebo [70].

3.1.19. Botulinum Toxin A

Botulinum toxin type A is an exotoxin released by the Gram-positive bacterium Clostridium botulinum. It (intradermal or submucosal injection; dose range, 25–75U) was found to effectively produce analgesia in patients with TN [70]; however, the drug can affect the neuromuscular abilities of the involved muscles.

3.1.20. Minocycline

Minocycline (MC) is a second-generation semi-synthetic tetracycline broad-spectrum antibiotic. It possesses a high lipophilicity, excellent tissue penetration, and a good anti-interference action. Nagpal Kalpana et al. investigated the central antinociceptive impact of nanoparticles loaded with minocycline hydrochloride and discovered that MC is uniquely central analgesic, suggesting that targeted nanoparticles could be employed to efficiently deliver the central antinociceptive action of TN. The findings imply that MC is an analgesic for TN, and the mechanism may be connected to a reduction in inflammatory factors [71].

3.1.21. Novel Agents Used to Treat TN

Basimglurant is a strong, selective, and safe mGlu5-negative allosteric modulator with excellent oral bioavailability and a long half-life that supports once-daily treatment in humans. mGluR5 is essential for neurotransmitter release and neurotransmitter postsynaptic response in the central and peripheral neural systems. mGlu5 at synaptic and extrasynaptic sites can boost NMDA receptor activation by boosting NMDA currents. Inhibiting the downstream actions of the mGlu5 receptor may reduce NMDA function. Except in cases of prior application for serious depression, basimglurant may have favorable outcomes in the treatment of TN. In NCT05142228, the TN pain-related outcomes after the injection of aimovig (erenumab) under the skin are being evaluated. Aimovig is the first antibody therapy targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor, and it has FDA approval for migraine prevention, is well tolerated, and has a good safety profile. CGRP plays a pivotal role in the formation and maintenance of NP. This trial is an expanded application of aimovig (erenumab) to TN [72,73,74].

4. Discussion

Conservative pharmacological management is considered the first-line treatment for TN. Despite the considerable number of drugs used, the medical management of this condition remains challenging. The aim of this systematic review was to provide an overview of previously published systematic reviews on the pharmacological management of TN. Eleven articles encompassing 31 pharmacological interventions were evaluated (Table 4).

Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine (daily recommended doses, 0.4–1.2 g and 0.9–1.8 g, respectively) have been considered the first line of treatment for pain management [5,75]. However, sleepiness, vertigo, nausea, double vision, and reduced neuromuscular control, as well as cognition issues, are the most frequent patient-reported side effects of these drugs, particularly in females [4]. Elevated levels of transaminases and hyponatremia are frequently observed in patients who receive higher doses of these medications. The presence of these side effects led to the search for other drugs that might prove beneficial for patients with TN.

One of the 11 articles included in the current systematic review indicated that there is a dearth of studies on the clinical efficacy of gabapentin as monotherapy for TN; only one study with high-grade evidence reported that ropivacaine (block) + gabapentin (oral administration) reduced pain and improved the quality of life of patients with TN [21,76].

Yang F. et al. recently published an NMA of eight different interventions for TN, but the primary treatment methods were not well defined [60]. They compared the response rates across studies, which might account for the discrepancy in findings with regard to pimozide, as indicated in Table 4. The comparison of response rates among studies might not yield clinically significant results because the treatment outcomes across these studies are not uniform. Another concern with regard to the study by Yang F. et al. was the advocacy of lidocaine as the first-line drug for TN. The studies included in the NMA had low-grade evidence in terms of the sample size and methodology used. Moreover, repeated applications due to the short duration of action of lidocaine could prove inconvenient for the patient. These findings were, subsequently, refuted by Steinberg in 2018 [9].

The review article by Alves et al. indicated that topiramate was not significantly different from the placebo in providing analgesia for patients with TN [56]; however, the finding was based on the results of one study only. Alternatively, the systematic review by Wang et al. in 2011 [6] reported that the efficacy of topiramate was initially similar to that of carbamazepine, but significantly improved after two months of therapy. However, the evidence levels of the studies included in their review were low. Therefore, further studies are needed to ascertain the clinical significance of the results. Nonetheless, we included the review by Alves et al. in the current study because it is the first and only systematic review to present the inefficacies of both dextromethorphan and proparacaine.

Gabapentin coupled with ropivacaine injections into trigger sites enhanced pain management and quality of life, while pregabalin was proven to be beneficial in TN patients after a year of follow-up [77,78,79]. Hu et al. recently conducted a systematic review of the therapeutic efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) injections for TN and discovered a response in approximately 70–100% of patients, with mean pain intensity and frequency reduced by approximately 60–80% and no major adverse events reported [80].

Various combinations of carbamazepine, lamotrigine, gabapentin, and baclofen have been used for secondary TN [5]; however, most of them carry low-grade evidence. Concomitant continuous pain is the most difficult to treat, and although carbamazepine monotherapy might not prove useful, gabapentin and pregabalin might have beneficial effects in reducing this pain [5].

Sridharan and Sivaramakrishnan [70] published a meta-analysis consisting of botulinum toxin A-related studies with high-grade evidence in 2017. Subsequently, Rubis et al. [77] published a comprehensive review article in 2022 which covered most of the randomized control trials on botulinum toxin A. Nonetheless, further studies on the dosage, number and frequency of injections, and side effects are warranted.

Sumatriptan, intranasal lidocaine, and intravenous lidocaine were reported to provide adequate analgesia, but most of the studies included in the review articles presented low-grade evidence [70,76]. However, the treatment outcome measures and other reporting items were well defined.

The article by Di Stefano published in 2018 is the most comprehensive review published to date [6]. In addition to reviewing the published studies, the article provided information about the new interventions that were under trial and illustrated the side effects of the drugs more comprehensively than other articles.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Among the numerous interventions available for TN, pharmacological management is the most conservative approach and should be the preferred mode of treatment. Taken together, the findings of the 11 review articles included in this study indicate that carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine continue to be the first-line medication for classical TN; however, their side effects limit their use to some extent. Lamotrigine and baclofen can be regarded as second-line drugs in patients who do not respond to the first-line medications or present with intolerable side effects. Carbamazepine can be combined with newer drugs tested within the past few years, such as gabapentin, ropivacaine, tizanidine, or pimozide, to yield better or equivalent results and improve the tolerance to treatment. Intravenous lidocaine can be used to treat acute pain, whereas botulinum toxin A might be used as refractory therapy. Proparacaine, dextromethorphan, and tocainide were generally reported to be inappropriate for treating TN. Except for carbamazepine, most of the drugs reviewed in our article were inadequately studied. Thus, further studies are required to ascertain their clinical significance. Furthermore, new research on combination therapies and newer formulations, such as vixotrigine, is warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. and G.D.; methodology, M.H.R. and A.A.G.K.; software, I.K.; validation, M.I., M.A.J. and M.S.H.; formal analysis, M.Z.K.; investigation, M.H.R. and S.S.; resources, I.K.; data cu-ration, G.D. and A.A.G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and G.D.; writing—review and editing, M.I., M.A.J. and G.D.; visualization, F.A.H.B. and M.A.K.; supervision, S.S.; project administra-tion, F.A.H.B. and M.S.H.; funding acquisition, I.K. and G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors appreciate the support of the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, in the form of a Large Research Group Project under grant number (RGP2/190/44).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This systematic review was performed and presented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) 2009 statement. The PICOS (participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design) method was used to determine the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, R.D. Principles of Neurology; Health Professions Division, McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bista, P.; Imlach, W.L. Pathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets for Trigeminal Neuropathic Pain. Medicines 2019, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Wang, D.; Zhou, J. International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition beta-based field testing of vestibular migraine in China: Demographic, clinical characteristics, audiometric findings and diagnosis statues. Cephalalgia 2016, 36, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, P.K. Familial occurrence of classical and idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J. Neurol. Sci. 2022, 434, 120101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.; Chong, M.S.; Shetty, A.; Zakrzewska, J.M. A systematic review of rescue analgesic strategies in acute exacerbations of primary trigeminal neuralgia. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e385–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, G.; Truini, A.; Cruccu, G. Current and Innovative Pharmacological Options to Treat Typical and Atypical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Drugs 2018, 78, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen Philip, J.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A.; KalsoEija, A. Carbamazepine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD005451. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.P.; Bai, M. Topiramate versus carbamazepine for the treatment of classical trigeminal neuralgia: A meta-analysis. CNS Drugs 2011, 25, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhou, H.Y.; Xiao, Z.L.; Wang, W.; Li, X.L.; Chen, S.J.; Yin, X.-P.; Xu, L.-J. Efficacy and Safety of Gabapentin vs. Carbamazepine in the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Meta-Analysis. Pain Pract. 2016, 16, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.I. Review: In trigeminal neuralgia, carbamazepine, botulinum toxin type A, or lidocaine improve response rate vs placebo. ACP J. Club. 2018, 169, C43-JC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiyer, R.; Mehta, N.; Gungor, S.; Gulati, A. A Systematic Review of NMDA Receptor Antagonists for Treatment of Neuropathic Pain in Clinical Practice. Clin. J. Pain. 2018, 34, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, R.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A. Clonazepam for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD009486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de León-Casasola, O.A.; Mayoral, V. The topical 5% lidocaine medicated plaster in localized neuropathic pain: A reappraisal of the clinical evidence. J. Pain. Res. 2016, 9, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A.; Quinlan, J. Topical lidocaine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, Cd010958. [Google Scholar]

- Plested, M.; Budhia, S.; Gabriel, Z. Pregabalin, the lidocaine plaster and duloxetine in patients with refractory neuropathic pain: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2010, 10, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masic, D.; Liang, E.; Long, C.; Sterk, E.J.; Barbas, B.; Rech, M.A. Intravenous Lidocaine for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Pharmacotherapy 2018, 38, 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.; Alam, S.M.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, M. Clinical efficacy and tolerability of Gabapentinoids with current prescription patterns in patients with Neuropathic pain. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj Paudel, K.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Rauniar, G.P.; Das, B.P. Comparison of antinociceptive effect of the antiepileptic drug gabapentin to that of various dosage combinations of gabapentin with lamotrigine and topiramate in mice and rats. J. Neuro. Rural. Pract. 2011, 2, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banday, M.; Syed Sameer, A.; Farhat, S.; Aziz, R. Gabapentin: A pharmacotherapeutic panacea. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 5, 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Bell, R.F.; Rice, A.S.C.; Tölle, T.R.; Phillips, T.; Moore, R.A. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD007938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.A.; Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Rice, A.S.C. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD007938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, P.C.P.; Dinh, H.Q.; Nguyen, K.; Lin, S.; Ong, Y.L.; Ariyawardana, A. Efficacy of gabapentin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, L.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A. Lacosamide for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD009318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.A.; Derry, S.; Aldington, D.; Cole, P.; Wiffen, P.J. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD008242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A. Lamotrigine for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, Cd006044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A.; Lunn, M.P.T. Levetiracetam for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD010943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn, M.P.T.; Hughes, R.A.C.; Wiffen, P.J. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD007115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Chen, N.; He, L.; Yang, M.; Zhu, C.; Wu, F. Oxcarbazepine for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, Cd007963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derry, S.; Phillips, T.; Moore, R.A.; Wiffen, P.J. Milnacipran for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD011789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birse, F.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A. Phenytoin for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, Cd009485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Aldington, D.; Moore, R.A. Nortriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, Cd011209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco Tarrio, E.; GálvezMateos, R.; Zamorano Bayarri, E.; López Gómez, V.; Pérez Páramo, M. Effectiveness of Pregabalin as Monotherapy or Combination Therapy for Neuropathic Pain in Patients Unresponsive to Previous Treatments in a Spanish Primary Care Setting. Clin. Drug Investig. 2013, 33, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derry, S.; Bell, R.F.; Straube, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Aldington, D.; Moore, R.A. Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, CD007076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauri, M.; Lazzari, M.; Casali, M.; Tufaro, G.; Sabato, E.; Sabato, A. Long-Term Efficacy of OROS Hydromorphone Combined with Pregabalin for Chronic Non-Cancer Neuropathic Pain. Clin. Drug Investig. 2014, 34, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, H.C.; Gallagher, R.M.; Butler, M.; Buggy, D.J.; Henman, M.C. Venlafaxine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, Cd011091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Lunn, M.P.T.; Moore, R.A. Topiramate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, CD008314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, L.; Moore, R.A.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Phillips, T. Desipramine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD011003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, D.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A. Valproic acid and sodium valproate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD009183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, S.; Aigner, M.; Ossege, M.; Pernicka, E.; Wildner, B.; Sycha, T. Antipsychotics for acute and chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, CD004844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.A.; Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Lunn, M.P. Zonisamide for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD011241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrzosek, A.; Woron, J.; Dobrogowski, J.; Jakowicka-Wordliczek, J.; Wordliczek, J. Topical clonidine for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD010967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duehmke, R.M.; Derry, S.; Wiffen, P.J.; Bell, R.F.; Aldington, D.; Moore, R.A. Tramadol for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD003726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, A.; Bleakley, C.; Hurley, D.A.; Gill, C.; Hannon-Fletcher, M.; Bell, P.; McDonough, S. Herbal medicinal products or preparations for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, CD010528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, R.; Gulati, A.; Gungor, S.; Bhatia, A.; Mehta, N. Treatment of chronic pain with various buprenorphine formulations: A systematic review of clinical studies. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 127, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Moore, R.A.; Stannard, C.; Aldington, D.; Cole, P.; Knaggs, R. Buprenorphine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD011603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.A.; Chi, C.C.; Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Rice, A.S. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, CD010902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiffen, P.J.; Knaggs, R.; Derry, S.; Cole, P.; Phillips, T.; Moore, R.A. Paracetamol [acetaminophen] with or without codeine or dihydrocodeine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, CD012227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Stannard, C.; Cole, P.; Wiffen, P.J.; Knaggs, R.; Aldington, D.; Moore, R.A. Fentanyl for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, CD011605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mücke, M.; Phillips, T.; Radbruch, L.; Petzke, F.; Häuser, W. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, CD012182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stannard, C.; Gaskell, H.; Derry, S.; Aldington, D.; Cole, P.; Cooper, T.E.; Knaggs, R.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A. Hydromorphone for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, CD011604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Moore, R.A. Topical capsaicin [low concentration] for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD010111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derry, S.; Rice, A.S.C.; Cole, P.; Tan, T.; Moore, R.A. Topical capsaicin [high concentration] for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD007393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNicol, E.D.; Ferguson, M.C.; Schumann, R. Methadone for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD012499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T.E.; Chen, J.; Wiffen, P.J.; Derry, S.; Carr, D.B.; Aldington, D.; Cole, P.; Moore, R.A. Morphine for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, CD011669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskell, H.; Derry, S.; Stannard, C.; Moore, R.A. Oxycodone for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, CD010692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaskell, H.; Moore, R.A.; Derry, S.; Stannard, C. Oxycodone for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, CD010692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo Alves, T.C.; Santos Azevedo, G.; Santiago de Carvalho, E. Pharmacological treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: Systematic review and metanalysis. Revista Anest. 2004, 54, 842–849. [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Sindrup, S.H.; Jensen, T.S. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain 2010, 150, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawahar, R.; Oh, U.; Yang, S.; Lapane, K.L. A systematic review of pharmacological pain management in multiple sclerosis. Drugs 2013, 73, 1711–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, M.; Zhou, M.; He, L.; Chen, N.; Zakrzewska, J.M. Non-antiepileptic drugs for trigeminal neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, Cd004029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Lin, Q.; Dong, L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, S. Efficacy of 8 different drug treatments for patients with trigeminal neuralgia: A network meta-analysis. Clin. J. Pain. 2018, 34, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadalouca, A.; Siafaka, I.; Argyra, E.; Vrachnou, E.V.I.; Moka, E. Therapeutic Management of Chronic Neuropathic Pain. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1088, 164–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murnion, B.P. Neuropathic pain: Current definition and review of drug treatment. Aust. Prescr. 2018, 41, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henze, T.; Rieckmann, P.; Toyka, K.V. Symptomatic treatment of multiple sclerosis: Multiple Sclerosis Therapy Consensus Group [MSTCG] of the German Multiple Sclerosis Society. Euro Neuro 2006, 56, 78–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chole, R.; Patil, R.; Degwekar, S.S.; Bhowate, R.R. Drug treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: A systematic review of the literature. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparro, L.E.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A.; Gilron, I. Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, CD008943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoliel, R.; Zini, A.; Khan, J.; Almoznino, G.; Sharav, Y.; Haviv, Y. Trigeminal neuralgia [part II]: Factors affecting early pharmacotherapeutic outcome. Cephalalgia 2016, 36, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backonja, M.-M.; Serra, J. REVIEW PAPERS Pharmacologic Management Part 1: Better-Studied Neuropathic Pain Diseases. Pain Med. 2004, 5, S28–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Oomens, M.; Forouzanfar, T. Pharmaceutical Management of Trigeminal Neuralgia in the Elderly. Drugs Aging 2015, 32, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bendtsen, L.; Zakrzewska, J.M.; Abbott, J.; Braschinsky, M.; Di Stefano, G.; Donnet, A.; Eide, P.K.; Leal, P.R.L.; Maarbjerg, S.; May, A.; et al. European Academy of Neurology guideline on trigeminal neuralgia. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagpal, K.; Singh, S.K.; Mishra, D.N. Minocycline encapsulated chitosan nanoparticles for central antinociceptive activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, M.A.; McPhee, S.J. (Eds.) Trigeminal Neuralgia; Quick Medical Diagnosis & Treatment; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Yu, W.; Gu, X. Potential novel therapeutic strategies for neuropathic pain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1138798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuki, M.; Kawamura, S.; Kashiwagi, K.; Tachikawa, S.; Koh, A. Erenumab in the treatment of comorbid trigeminal neuralgia in patients with migraine. Cureus 2023, 15, e35913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridharan, K.; Sivaramakrishnan, G. Interventions for Refractory Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Bayesian Mixed Treatment Comparison Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Clin. Drug Investig. 2017, 37, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, G.; Truini, A. Pharmacological treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2017, 17, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubis, A.; Juodzbalys, G. The Use of Botulinum Toxin A in the Management of Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Res. 2020, 11, e2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cruccu, G.; Gronseth, G.; Alksne, J.; Argoff, C.; Brainin, M.; Burchiel, K.; Nurmikko, T.; Zakrzewska, J.M. AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management. Eur. J. Neurol. 2008, 15, 1013–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montano, N.; Conforti, G.; Di Bonaventura, R.; Meglio, M.; Fernandez, E.; Papacci, F. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2015, 24, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Guan, X.; Fan, L.; Li, M.; Liao, Y.; Nie, Z.; Jin, L. Therapeutic efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in trigeminal neuralgia: A systematic review. J. Headache Pain 2013, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).