Prescriptions of Antipsychotics in Younger and Older Geriatric Patients with Polypharmacy, Their Safety, and the Impact of a Pharmaceutical-Medical Dialogue on Antipsychotic Use

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

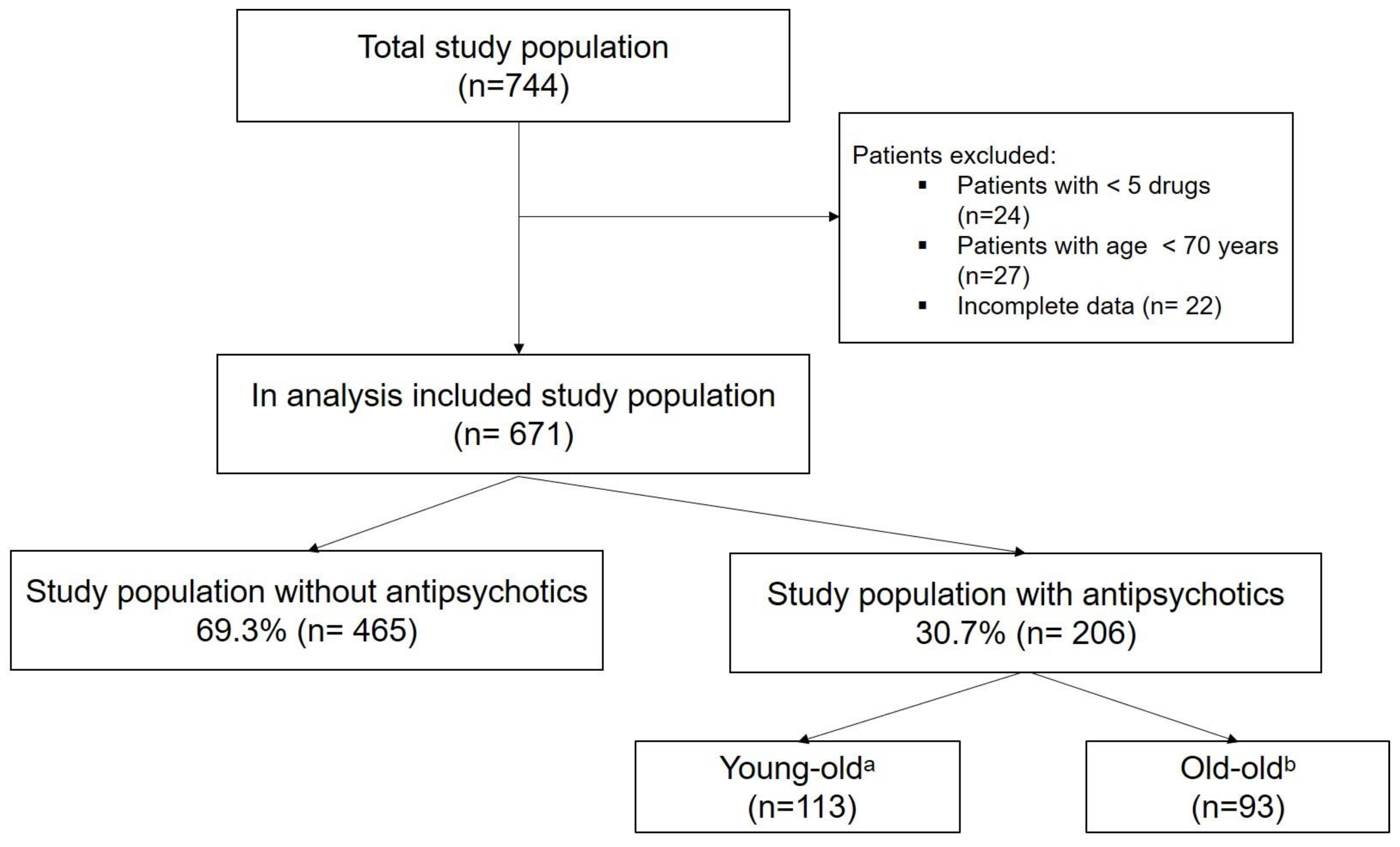

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Statistical Methods

2.4. Ethics Consideration

3. Results

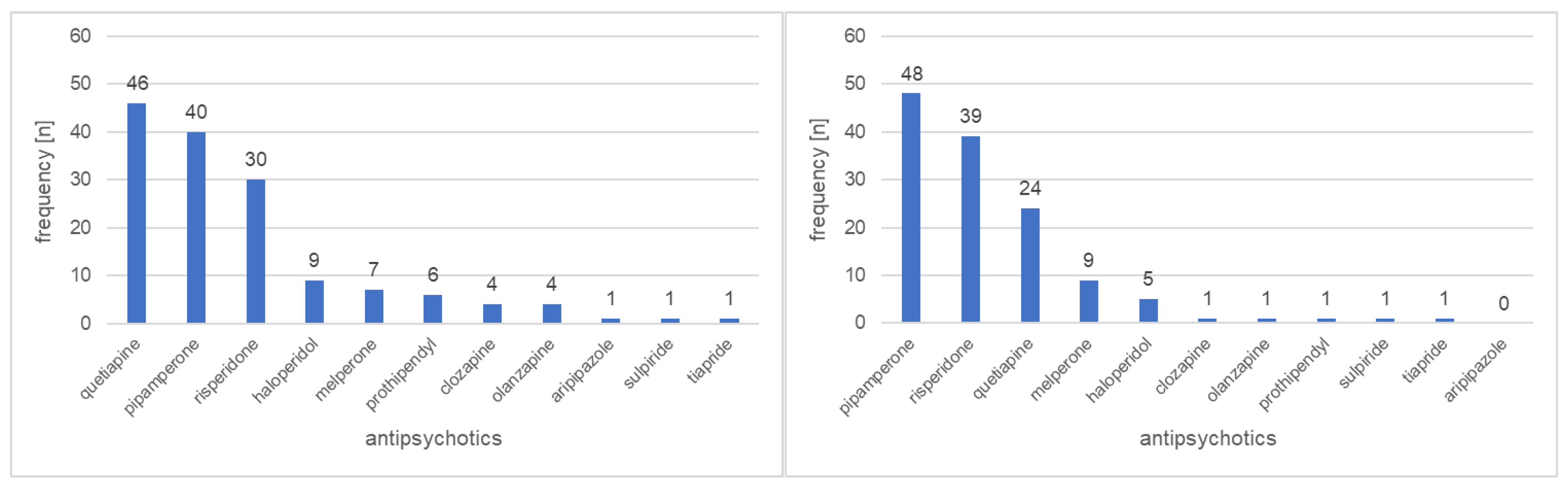

3.1. Prescribing Patterns

3.2. Safety of Medications Used

3.3. Impact of a Pharmaceutical Medical Consolation

4. Discussion

4.1. Prescribing Patterns

4.2. Safety of Medications Used

4.3. Impact of a Pharmaceutical Medical Consolation

4.4. Strengths and Weaknesses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fabbri, E.; Zoli, M.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Salive, M.E.; Studenski, S.A.; Ferrucci, L. Aging and Multimorbidity: New Tasks, Priorities, and Frontiers for Integrated Gerontological and Clinical Research. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazzara, M.B.; Palmer, K.; Vetrano, D.L.; Carfì, A.; Onder, G. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: A narrative review of the literature. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Pérez, M.I.; Fierro, I.; Salgueiro-Vázquez, M.E.; Sáinz-Gil, M.; Martín-Arias, L.H. A cross-sectional study of psychotropic drug use in the elderly: Consuming patterns, risk factors and potentially inappropriate use. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2021, 28, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lähteenvuo, M.; Tiihonen, J. Antipsychotic Polypharmacy for the Management of Schizophrenia: Evidence and Recommendations. Drugs 2021, 81, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkham, J.; Sherman, C.; Velkers, C.; Maxwell, C.; Gill, S.; Rochon, P.; Seitz, D. Antipsychotic Use in Dementia. Can. J. Psychiatry 2017, 62, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerre, L.M.; Farrell, B.; Hogel, M.; Graham, L.; Lemay, G.; McCarthy, L.; Raman-Wilms, L.; Rojas-Fernandez, C.; Sinha, S.; Thompson, W.; et al. Deprescribing antipsychotics for behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia and insomnia: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can. FAm. Physician 2018, 64, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Berk, M.; Brietzke, E.; Goldstein, B.I.; López-Jaramillo, C.; Kessing, L.V.; Malhi, G.S.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Majeed, A.; et al. Bipolar disorders. Lancet 2020, 396, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Fornaro, M.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Zangani, C.; Croatto, G.; Monaco, F.; Krinitski, D.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Correll, C.U. Safety of 80 antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-attention-deficit/hyperactivity medications and mood stabilizers in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders: A large scale systematic meta-review of 78 adverse effects. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadogan, C.A.; Ryan, C.; Hughes, C.M. Appropriate Polypharmacy and Medicine Safety: When Many is not Too Many. Drug Saf. 2016, 39, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnell, K.; Jonasdottir Bergman, G.; Fastbom, J.; Danielsson, B.; Borg, N.; Salmi, P. Psychotropic drugs and the risk of fall injuries, hospitalisations and mortality among older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2017, 32, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Miller, G.; Khoury, R.; Grossberg, G.T. Rational deprescribing in the elderly. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 31, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gareri, P.; Segura-García, C.; Manfredi, V.G.; Bruni, A.; Ciambrone, P.; Cerminara, G.; De Sarro, G.; De Fazio, P. Use of atypical antipsychotics in the elderly: A clinical review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divac, N.; Prostran, M.; Jakovcevski, I.; Cerovac, N. Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 656370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, L.S.; Dagerman, K.; Insel, P.S. Efficacy and adverse effects of atypical antipsychotics for dementia: Meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 14, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralph, S.J.; Espinet, A.J. Increased All-Cause Mortality by Antipsychotic Drugs: Updated Review and Meta-Analysis in Dementia and General Mental Health Care. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2018, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, T.S.; Gray, N. Management of common adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. World Psychiatry 2018, 17, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.Y.; Choi, N.K.; Jung, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Kwon, J.S.; Park, B.J. Risk of ischemic stroke with the use of risperidone, quetiapine and olanzapine in elderly patients: A population-based, case-crossover study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 27, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, S.; Fernandez-Enright, F.; Huang, X.F. Structural contributions of antipsychotic drugs to their therapeutic profiles and metabolic side effects. J. Neurochem. 2012, 120, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazan, F.; Gercke, Y.; Weiss, C.; Wehling, M. The U.S.-FORTA (Fit fOR The Aged) List: Consensus Validation of a Clinical Tool to Improve Drug Therapy in Older Adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 439.e9–439.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [CrossRef]

- Hefner, G.; Hahn, M.; Toto, S.; Hiemke, C.; Roll, S.C.; Wolff, J.; Klimke, A. Potentially inappropriate medication in older psychiatric patients. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 77, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, K.; Flicker, L.; Page, A.; Etherton-Beer, C. Deprescribing in Frail Older People: A Randomised Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangoni, A.A.; Jackson, S.H. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: Basic principles and practical applications. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 57, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrall, D.; Just, K.S.; Schmid, M.; Stingl, J.C.; Sachs, B. Adverse drug reactions in older adults: A retrospective comparative analysis of spontaneous reports to the German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangin, D.; Bahat, G.; Golomb, B.A.; Mallery, L.H.; Moorhouse, P.; Onder, G.; Petrovic, M.; Garfinkel, D. International Group for Reducing Inappropriate Medication Use & Polypharmacy (IGRIMUP): Position Statement and 10 Recommendations for Action. Drugs Aging 2018, 35, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, D.; Mangin, D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: Addressing polypharmacy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 1648–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlmey, A. Alter Neu Denken. Available online: https://www.charite.de/forschung/themen_forschung/alter_neu_denken/ (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Behrman, S.; Burgess, J.; Topiwala, A. Prescribing antipsychotics in older people: A mini-review. Maturitas 2018, 116, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamón, V.; Hurtado, I.; Salazar-Fraile, J.; Sanfélix-Gimeno, G. Treatment patterns and appropriateness of antipsychotic prescriptions in patients with schizophrenia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Tan, C.-C.; Xu, W.; Hu, H.; Cao, X.-P.; Dong, Q.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.-T. The Prevalence of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2020, 73, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieck, K.M.; Pagali, S.; Miller, D.M. Delirium in hospitalized older adults. Hosp. Pract. 2020, 48, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, A.; Bellelli, G. Delirium superimposed on dementia. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2020, 11, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastesson, J.W.; Morin, L.; Tan, E.C.K.; Johnell, K. An update on the clinical consequences of polypharmacy in older adults: A narrative review. Expert. Opin. Drug Saf. 2018, 17, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnell, K.; Klarin, I. The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: A study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Drug Saf. 2007, 30, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, R.; Schmitz, K.; Griesel, C.; Heidenreich, A.; Schulz, J.B.; Trautwein, C.; Marx, N.; Fitzner, C.; Jaehde, U.; Eisert, A. Comprehensive pharmaceutical care to prevent drug-related readmissions of dependent-living elderly patients: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiesel, E.K.; Drey, M.; Pudritz, Y.M. Influence of a ward-based pharmacist on the medication quality of geriatric inpatients: A before–after study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Slack, M.K.; Martin, J.; Ehrman, C.; Chisholm-Burns, M. Geriatric patient care by U.S. pharmacists in healthcare teams: Systematic review and meta-analyses. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rösler, A.; Mißbach, P.; Kaatz, F.; Kopf, D. [Pharmacist rounds on geriatric wards : Assessment of 1 year of pharmaceutical counseling]. Z Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 51, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazan, F.; Wehling, M. Polypharmacy in older adults: A narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, P.; Woolford, S.J.; Patel, H.P. Multi-Morbidity and Polypharmacy in Older People: Challenges and Opportunities for Clinical Practice. Geriatrics 2020, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błeszyńska, E.; Wierucki, Ł.; Zdrojewski, T.; Renke, M. Pharmacological Interactions in the Elderly. Medicina 2020, 56, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshanberi, A.M. Recent Updates on Risk and Management Plans Associated with Polypharmacy in Older Population. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age 70–84 n = 113 (%) | Age 85–100 n = 93 (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 79 ± 4 | 90 ± 4 | <0.001 T-Test |

| Female gender | 69 (61.1%) | 51 (54.8%) | 0.37 |

| Polypharmacy (>10 drugs) | 90 (79.6%) | 68 (73.1%) | 0.27 |

| Number of drugs per patient | |||

| Before recommendation a | 14 ± 4 | 13 ± 4 | 0.30 T-Test |

| After recommendation a | 14 ± 4 | 13 ± 4 | 0.47 T-Test |

| Renal insufficiency stages | <0.001 | ||

| stage 1 | 37 (32.7%) | 9 (9.7%) | |

| stage 2 | 40 (35.4%) | 31 (33.3%) | |

| stage 3 | 33 (29.2%) | 44 (47.3%) | |

| stage 4 | 3 (2.7%) | 9 (9.7%) | |

| stage 5 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Renal glomerular filtration rate | 0.03 | ||

| >30 mL/min (stage ≤3) | 110 (97.3%) | 84 (90.3%) | |

| ≤30 mL/min (stage ≥4) | 3 (2.7%) | 9 (9.7%) |

| Age 70–84 n = 113 (%) | Age 85–100 n = 93 (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antipsychotics | |||

| High potency (monotherapy) | 18 (15.9%) | 11 (11.8%) | 0.40 |

| Aripiprazole | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Haloperidol | 5 (4.4%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0.46 * |

| Olanzapine | 3 (2.7%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.63 * |

| Risperidone | 10 (8.8%) | 8 (8.6%) | 0.95 |

| Medium potency (monotherapy) | 38 (33.6%) | 25 (26.9%) | 0.30 |

| Clozapine | 3 (2.7%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.63 * |

| Quetiapine | 34 (30.1%) | 22 (23.7%) | 0.30 |

| Sulpiride | 1 (0.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1.00 * |

| Tiapride | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.45 * |

| Low potency (monotherapy) | 23 (20.4%) | 22 (23.7%) | 0.57 |

| Melperone | 3 (2.7%) | 6 (6.5%) | 0.31 * |

| Pipamperone | 16 (14.2%) | 16 (17.2%) | 0.57 |

| Prothipendyl | 4 (3.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.13 * |

| Combination of different Potencies a | 34 (30.1%) | 35 (37.6%) | 0.25 |

| Pipamperone + Risperidone | 17 (15.0%) | 28 (30.1%) | 0.01 |

| Pipamperone + Quetiapine | 4 (3.5%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.38 * |

| Other combinations b | 13 (11.5%) | 6 (6.5%) | 0.21 |

| Antipsychotic Drug | Indication | Loading Dose a | Increase/Maximum Dose a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haloperidol | Delirium in dementia a (2nd choice) | Loading dose 0.5 mg (oral) | If necessary, gradually increase up to max 5 mg/day in 2 doses. |

| Melperone | Sleeping disorders, psychomotor agitation | Gradual dosing with 25 mg (oral) at night | If necessary, increase in 25 mg increments. Max. 150 mg/day in 2–4 doses. |

| Pipamperone | Sleeping disorders, psychomotor agitation | Gradual dosing with 20 mg (oral) at night | If necessary, increase dose to 40 mg single dose, Max. three times daily (=120 mg/day) |

| Quetiapine | Psychotic symptoms in Parkinson’s disease | Gradual dosing with 12.5 mg (oral) | If response is inadequate, increase dose to 25 mg, then further increase in 25 mg increments if necessary. Max. 150 mg/day in 2 doses. |

| Risperidone | Delir in dementiaa (1st choice) | Gradual dosing with 2 × 0.25 mg/day (oral) | If response is inadequate, increase dose by 0.25 mg increments to up to 1 mg twice daily. For the majority of patients, the optimal dose is 2 × 0.5 mg/day. |

| Age 70–84 n = 113 (%) | Age 85–100 n = 93 (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication and drug selection | 12 (10.6%) | 7 (7.5%) | 0.45 |

| Overuse b | 8 (7.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.04 * |

| Underuse b | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Inadequate care b | 4 (3.5%) | 6 (6.5%) | 0.35 * |

| Dosage c | 4 (3.5%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.38 * |

| Application d | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.50 * |

| Interaction e | 19 (16.8%) | 11 (11.8%) | 0.33 |

| Side effects f | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.45 * |

| Drug documentation error | 2 (1.8%) | 3 (3.2%) | 0.66 * |

| Dependent Variables | |||||||||||||||||||

| Total study population (n = 206) | Independent variables | Total ADRs b | ADR Sub-Items: | ||||||||||||||||

| Indication/Drug Selection | Overuse | Inadequate Care | Dosage | Application | Interaction c | Side Effects | Drug Documentation Error | ||||||||||||

| adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | adjOR | 95% CI | ||

| Gender | 0.98 | 0.51-.1.89 | 1.04 | 0.40–2.74 | 0.70 | 0.17–2.90 | d | 0.27 | 0.03–2.76 | 1.62 | 0.08–31.37 | 1.03 | 0.46–2.33 | d | 2.09 | 0.34–12.89 | |||

| Age | 0.95 | 0.90–1.00 | 1.01 | 0.94–1.10 | 0.98 | 0.88–1.09 | d | 0.85 | 0.72–1.01 | 0.89 | 0.66–1.20 | 0.95 | 0.89–1.02 | d | 1.01 | 0.87–1.18 | |||

| GFR | 1.01 | 1.00–1.03 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | 1.01 | 0.97–1.04 | d | 1.00 | 0.96–1.05 | d | 1.02 | 1.00–1.04 | d | 0.98 | 0.94–1.03 | ||||

| Number of drugs | 1.10 | 1.02–1.20 | 1.03 | 0.91–1.16 | 0.95 | 0.80–1.14 | d | 1.16 | 0.93–1.46 | 0.88 | 0.55–1.43 | 1.12 | 1.02–1.24 | d | 0.97 | 0.78–1.21 | |||

| Age 70–84 (n = 113) | Gender | 0.82 | 0.35–1.90 | 0.59 | 0.14–2.43 | 0.65 | 0.11–3.75 | 0.38 | 0.03–4.37 | 0.40 | 0.04–4.50 | 2.12 | 0.09–51.77 | 0.83 | 0.29–2.38 | d | 0.78 | 0.03–19.67 | |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.87–1.07 | 1.21 | 0.99–1.48 | 1.38 | 1.02–1.89 | 1.00 | 0.76–1.31 | 0.81 | 0.63–1.05 | 0.96 | 0.65–1.41 | 0.92 | 0.81–1.04 | d | 1.11 | 0.71–1.73 | ||

| GFR | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 1.01 | 0.97–1.05 | 1.06 | 0.98–1.14 | 1.02 | 0.96–1.08 | d | 1.01 | 0.98–1.03 | d | 0.94 | 0.87–1.03 | |||

| Number of drugs | 1.05 | 0.95–1.17 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.20 | 0.89 | 0.70–1.13 | 1.23 | 0.92–1.63 | 1.13 | 0.86–1.48 | 0.85 | 0.51–1.42 | 1.06 | 0.93–1.20 | d | 0.96 | 0.65–1.40 | ||

| Age 85–100 (n = 93) | Gender | 1.28 | 0.42–3.93 | 2.95 | 0.53–16.44 | d | 2.31 | 0.39–13.74 | d | d | 1.55 | 0.36–6.62 | d | 2.10 | 0.18–24.74 | ||||

| Age | 0.80 | 0.65–0.99 | 0.88 | 0.66–1.16 | d | 0.86 | 0.62–1.18 | d | d | 0.79 | 0.60–1.06 | d | 0.86 | 0.55–1.33 | |||||

| GFR | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 1.00 | 0.96–1.04 | d | 1.02 | 0.97–1.06 | d | d | 1.04 | 1.00–1.08 | d | 1.01 | 0.95–1.07 | |||||

| Number of drugs | 1.24 | 1.05–1.47 | 1.06 | 0.87–1.28 | d | 1.06 | 0.87–1.31 | d | d | 1.31 | 1.07–1.61 | d | 0.99 | 0.73–1.33 | |||||

| Age 70–84 n = 113 (%) | Age 85–100 n = 93 (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TDM recommendations a | |||

| Accepted | 10 (8.8%) | 6 (6.5%) | 0.52 * |

| Laboratory control | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0.20 |

| ECG check | 6 (5.3%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0.30 |

| Patient monitoring for symptoms, side effects, and/or effect alone | 4 (3.5%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0.69 |

| Rejected | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.50 |

| No recommendation | 101 (89.4%) | 87 (93.5%) | 0.29 * |

| Medication modification recommendations | |||

| Accepted | 20 (17.7%) | 13 (14.0%) | 0.47 * |

| Drug onset | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1.%) | 0.45 |

| Drug discontinuation | 16 (14.2%) | 6 (6.5%) | 0.08 * |

| Drug changes | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0.20 |

| Dosage changes | 2 (1.8%) | 4 (4.3%) | 0.41 |

| Dosage form changes | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.50 |

| Rejected | 4 (3.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.13 |

| No recommendation | 89 (78.8%) | 80 (86.0%) | 0.18 * |

| Active Agent/s | Adverse Drug Reaction | Pharmaceutical Intervention Recommendation | Geriatrician’s Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbamazepine and quetipaine | CYP3A4- interaction: Loss of effect of quetiapine may occur. | Risk-benefit consideration of carbamazepine due to high side effect potential and interactions. Tapering of carbamazepine. | Tapering of carbamazepine (with concomitant administration of other anticonvulsants). |

| Quetiapine sustained-release tablets | Quetiapine sustained-release tablets are mortared as a non-mortar dosage form. Loss of the retarded effect. | Change to unretarded dosage form with examination and, if necessary, adjustment of the dose interval. | Changeover to unretarded dosage form occurs. |

| Quetiapine and citalopram | Risk of QT prolongation with arrhythmia. | ECG * and electrolyte controls with drug combination. | Close ECG and electrolyte controls were ordered. |

| Quinagolide and pipamperone | Dopamin-Agonist vs. Dopamin- Antagonist. Mutual loss of effect possible. | Deprescribing of pipamperone recommended. | Pipamperone discontinued and patient observed for the need of further drug therapy. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gebauer, E.-M.; Lukas, A. Prescriptions of Antipsychotics in Younger and Older Geriatric Patients with Polypharmacy, Their Safety, and the Impact of a Pharmaceutical-Medical Dialogue on Antipsychotic Use. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3127. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123127

Gebauer E-M, Lukas A. Prescriptions of Antipsychotics in Younger and Older Geriatric Patients with Polypharmacy, Their Safety, and the Impact of a Pharmaceutical-Medical Dialogue on Antipsychotic Use. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(12):3127. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123127

Chicago/Turabian StyleGebauer, Eva-Maria, and Albert Lukas. 2022. "Prescriptions of Antipsychotics in Younger and Older Geriatric Patients with Polypharmacy, Their Safety, and the Impact of a Pharmaceutical-Medical Dialogue on Antipsychotic Use" Biomedicines 10, no. 12: 3127. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123127

APA StyleGebauer, E.-M., & Lukas, A. (2022). Prescriptions of Antipsychotics in Younger and Older Geriatric Patients with Polypharmacy, Their Safety, and the Impact of a Pharmaceutical-Medical Dialogue on Antipsychotic Use. Biomedicines, 10(12), 3127. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123127