Microglia and Cholesterol Handling: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

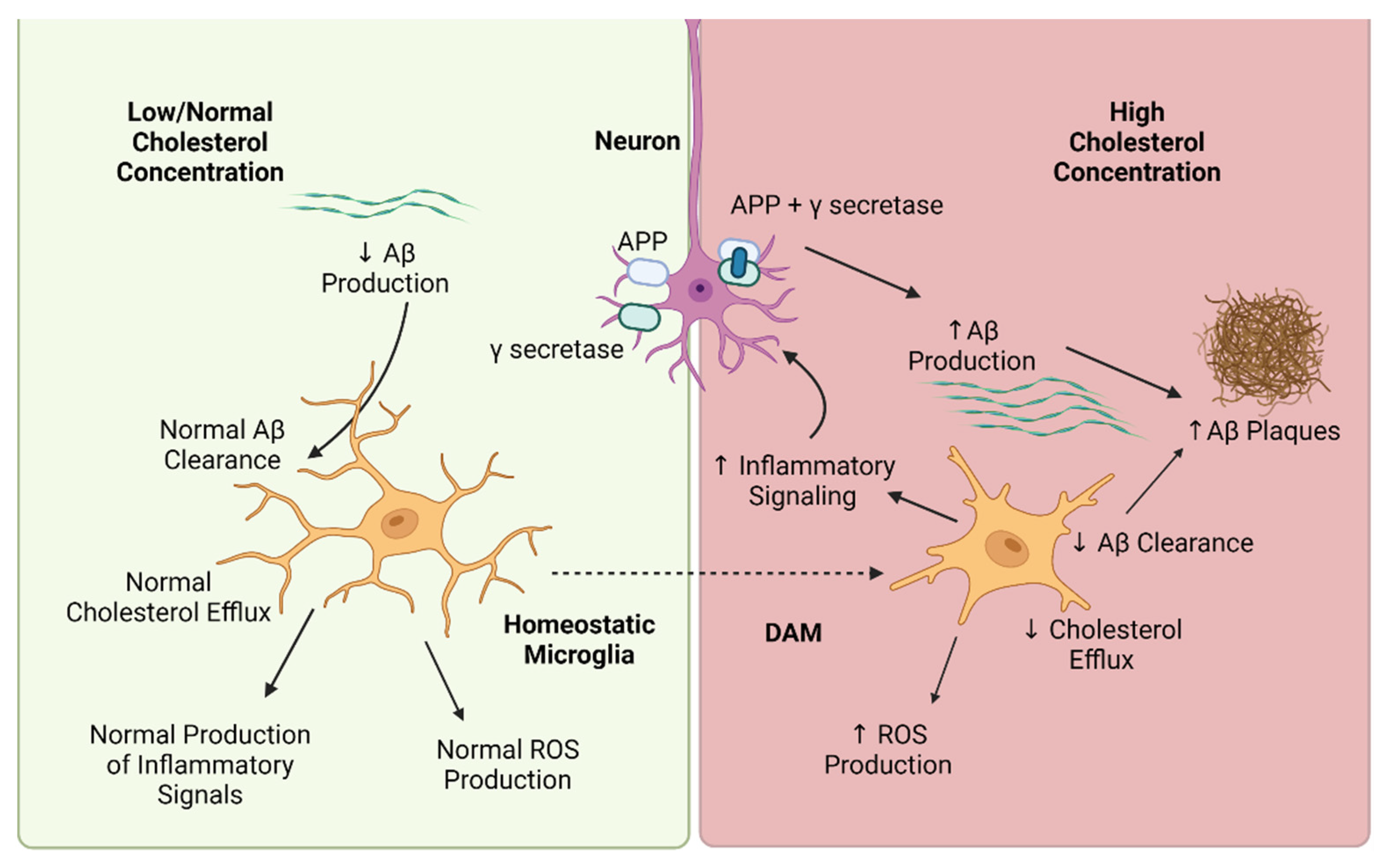

2. Cholesterol-Mediated Regulation of Microglia Phenotype

3. Cholesterol-Mediated Regulation of Microglia Function

4. Effects of Statins on Microglia

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Hippius, H.; Neundörfer, G. The Discovery of Alzheimer’s Disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 5, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Kulas, J.A.; Wang, C.; Holtzman, D.M.; Ferris, H.A.; Hansen, S.B. Regulation of Beta-Amyloid Production in Neurons by Astrocyte-Derived Cholesterol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2102191118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.Y.; Chang, C.C.Y.; Harned, T.C.; De La Torre, A.L.; Lee, J.; Huynh, T.N.; Gow, J.G. Blocking Cholesterol Storage to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease. Explor. Neuroprot. Ther. 2021, 1, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.-Y.; Yamauchi, Y.; Hasan, M.T.; Chang, C. Cellular Cholesterol Homeostasis and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Lipid Res. 2017, 58, 2239–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storch, J.; Xu, Z. Niemann-Pick C2 (NPC2) and Intracellular Cholesterol Trafficking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1791, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, S.R. NPC Intracellular Cholesterol Transporter 1 (NPC1)-Mediated Cholesterol Export from Lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 1706–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urano, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Murphy, S.R.; Shibuya, Y.; Geng, Y.; Peden, A.A.; Chang, C.C.Y.; Chang, T.Y. Transport of LDL-Derived Cholesterol from the NPC1 Compartment to the ER Involves the Trans-Golgi Network and the SNARE Protein Complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16513–16518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverter, M.; Rentero, C.; de Muga, S.V.; Alvarez-Guaita, A.; Mulay, V.; Cairns, R.; Wood, P.; Monastyrskaya, K.; Pol, A.; Tebar, F.; et al. Cholesterol Transport from Late Endosomes to the Golgi Regulates T-SNARE Trafficking, Assembly, and Function. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 4108–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liscum, L.; Dahl, N.K. Intracellular Cholesterol Transport. J. Lipid Res. 1992, 33, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Yokoyama, S.; Chang, T.-Y. ABCA1-Dependent Sterol Release: Sterol Molecule Specificity and Potential Membrane Domain for HDL Biogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abi-Mosleh, L.; Infante, R.E.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. Cyclodextrin Overcomes Deficient Lysosome-to-Endoplasmic Reticulum Transport of Cholesterol in Niemann-Pick Type C Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19316–19321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Iwamoto, N.; Rogers, M.A.; Abe-Dohmae, S.; Fujimoto, T.; Chang, C.C.Y.; Ishigami, M.; Kishimoto, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Ueda, K.; et al. Deficiency in the Lipid Exporter ABCA1 Impairs Retrograde Sterol Movement and Disrupts Sterol Sensing at the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 23464–23477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Brown, M.S.; Anderson, D.D.; Goldstein, J.L.; Radhakrishnan, A. Three Pools of Plasma Membrane Cholesterol and Their Relation to Cholesterol Homeostasis. eLife 2014, 3, e02882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmin, B.; Pipalia, N.H.; Lund, F.W.; Ramlall, T.F.; Sokolov, A.; Eliezer, D.; Maxfield, F.R. STARD4 Abundance Regulates Sterol Transport and Sensing. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 4004–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, J.; Pan, M.; Chin, H.F.; Lund, F.W.; Maxfield, F.R.; Breslow, J.L. STARD4 Knockdown in HepG2 Cells Disrupts Cholesterol Trafficking Associated with the Plasma Membrane, ER, and ERC. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 2716–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, J.; Li, S.; Fairall, L.; Pfisterer, S.G.; Gurnett, J.E.; Xiao, X.; Weston, T.A.; Vashi, D.; Ferrari, A.; Orozco, J.L.; et al. Aster Proteins Facilitate Nonvesicular Plasma Membrane to ER Cholesterol Transport in Mammalian Cells. Cell 2018, 175, 514–529.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Ercan, B.; Krshnan, L.; Triebl, A.; Koh, D.H.Z.; Wei, F.-Y.; Tomizawa, K.; Torta, F.T.; Wenk, M.R.; Saheki, Y. Movement of Accessible Plasma Membrane Cholesterol by the GRAMD1 Lipid Transfer Protein Complex. eLife 2019, 8, e51401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, T.; Chang, T.-Y.; Haass, C.; Ihara, Y. Accumulation and Aggregation of Amyloid β-Protein in Late Endosomes of Niemann-Pick Type C Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 4454–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiȩckowska-Gacek, A.; Mietelska-Porowska, A.; Chutorański, D.; Wydrych, M.; Długosz, J.; Wojda, U. Western Diet Induces Impairment of Liver-Brain Axis Accelerating Neuroinflammation and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 654509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Lai, K.; Zhong, Q.; Demin, K.A.; Kalueff, A.V.; Song, C. High-Glucose/High-Cholesterol Diet in Zebrafish Evokes Diabetic and Affective Pathogenesis: The Role of Peripheral and Central Inflammation, Microglia and Apoptosis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 96, 109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Q. Cholesterol Metabolism and Homeostasis in the Brain. Protein Cell 2015, 6, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-P.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Toh, B.H.; McLean, C.; Li, H. Cholesterol Involvement in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2010, 43, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglielli, L.; Tanzi, R.E.; Kovacs, D.M. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Cholesterol Connection. Nat. Neurosci. 2003, 6, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and Microglial Activation in Alzheimer Disease: Where Do We Go from Here? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.V.; Hanson, J.E.; Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrak, R.E. Microglia in Alzheimer Brain: A Neuropathological Perspective. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 2012, 165021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlus, H.; Heneka, M.T. Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streit, W.J. Microglia and Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 77, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulian, D. Microglia and the Immune Pathology of Alzheimer Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999, 65, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escott-Price, V.; Bellenguez, C.; Wang, L.-S.; Choi, S.-H.; Harold, D.; Jones, L.; Holmans, P.; Gerrish, A.; Vedernikov, A.; Richards, A.; et al. Gene-Wide Analysis Detects Two New Susceptibility Genes for Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, I.E.; Savage, J.E.; Watanabe, K.; Bryois, J.; Williams, D.M.; Steinberg, S.; Sealock, J.; Karlsson, I.K.; Hägg, S.; Athanasiu, L.; et al. Genome-Wide Meta-Analysis Identifies New Loci and Functional Pathways Influencing Alzheimer’s Disease Risk. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellenguez, C.; Küçükali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; et al. New Insights into the Genetic Etiology of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bis, J.C.; Jian, X.; Kunkle, B.W.; Chen, Y.; Hamilton-Nelson, K.L.; Bush, W.S.; Salerno, W.J.; Lancour, D.; Ma, Y.; Renton, A.E.; et al. Whole Exome Sequencing Study Identifies Novel Rare and Common Alzheimer’s-Associated Variants Involved in Immune Response and Transcriptional Regulation. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 1859–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karch, C.M.; Goate, A.M. Alzheimer’s Disease Risk Genes and Mechanisms of Disease Pathogenesis. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 77, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelzmann, R.A.; Norman Schnitzlein, H.; Reed Murtagh, F. An English Translation of Alzheimer’s 1907 Paper, “über Eine Eigenartige Erkankung Der Hirnrinde”. Clin. Anat. 1995, 8, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keren-Shaul, H.; Spinrad, A.; Weiner, A.; Matcovitch-Natan, O.; Dvir-Szternfeld, R.; Ulland, T.K.; David, E.; Baruch, K.; Lara-Astaiso, D.; Toth, B.; et al. A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 2017, 169, 1276–1290.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, M.B.; Kösel, S.; Egensperger, R.; Banati, R.B.; Müller, U.; Bise, K.; Hoff, P.; Möller, H.J.; Fujisawa, K.; Mehraein, P. Rediscovery of the Case Described by Alois Alzheimer in 1911: Historical, Histological and Molecular Genetic Analysis. Neurogenetics 1997, 1, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, L.S.; Scott, S.A.; Barrón, E.; Chui, H.C. MHC Class II-Positive Microglia in Human Brain: Association with Alzheimer Lesions: MHC Class II Microglia in Human Brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 1992, 33, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozemuller, J.M.; van der^Valk, P.; Eikelenboom, P. Activated Microglia and Cerebral Amyloid Deposits in Alzheimer’s Disease. Res. Immunol. 1992, 143, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Hussain, M.D.; Yan, L.-J. Microglia, Neuroinflammation, and Beta-Amyloid Protein in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Neurosci. 2014, 124, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-H.; Fu, Y.-C.; Zhang, D.-W.; Yin, K.; Tang, C.-K. Foam Cells in Atherosclerosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013, 424, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruth, H.S. Macrophage Foam Cells and Atherosclerosis. Front. Biosci. 2001, 6, d429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, P.; Ye, J. Lipid Homeostasis and the Formation of Macrophage-Derived Foam Cells in Atherosclerosis. Protein Cell 2012, 3, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, W.; Melnik, M.; Huang, C.; Teter, B.; Chandra, S.; Zhu, C.; McIntire, L.B.; John, V.; Gylys, K.H.; Bilousova, T. Multi-Omics Analysis of Microglial Extracellular Vesicles From Human Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Tissue Reveals Disease-Associated Signatures. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 766082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y.D.; Tse, W.; Smith, J.D.; Landreth, G.E. Apolipoprotein E Promotes β-Amyloid Trafficking and Degradation by Modulating Microglial Cholesterol Levels. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 2032–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Barres, B.A. Microglia and Macrophages in Brain Homeostasis and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegelmilch, T.; Henke, K.; Peri, F. Microglia in the Developing Brain: From Immunity to Behaviour. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011, 21, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerjahn, A.; Kirchhoff, F.; Helmchen, F. Resting Microglial Cells Are Highly Dynamic Surveillants of Brain Parenchyma in Vivo. Science 2005, 308, 1314–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peri, F.; Nüsslein-Volhard, C. Live Imaging of Neuronal Degradation by Microglia Reveals a Role for V0-ATPase A1 in Phagosomal Fusion In Vivo. Cell 2008, 133, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, T.R.; Dufort, C.; Dissing-Olesen, L.; Giera, S.; Young, A.; Wysoker, A.; Walker, A.J.; Gergits, F.; Segel, M.; Nemesh, J.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Microglia throughout the Mouse Lifespan and in the Injured Brain Reveals Complex Cell-State Changes. Immunity 2019, 50, 253–271.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Darmanis, S.; Neff, N.F.; Okamoto, J.; Gulati, G.; Bennett, M.L.; Sun, L.O.; Clarke, L.E.; et al. Developmental Heterogeneity of Microglia and Brain Myeloid Cells Revealed by Deep Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Neuron 2019, 101, 207–223.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Nguyen, L.T.M.; Pan, H.; Hassan, S.; Dai, Y.; Xu, J.; Wen, Z. Two Phenotypically and Functionally Distinct Microglial Populations in Adult Zebrafish. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabd1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, M.; Menon, V.; Habib, N.; Taga, M.F.; Ma, Y.; Yung, C.J.; Cimpean, M.; Khairallah, A.; Coronas-Samano, G.; Sankowski, R.; et al. Single Cell RNA Sequencing of Human Microglia Uncovers a Subset Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, G. Measuring Brain Lipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1851, 1026–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, D.J.; Small, D.M. Physical Chemistry of Bile. In Comprehensive Physiology; Terjung, R., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989; pp. 621–662. [Google Scholar]

- von Eckardstein, A.; Nofer, J.-R.; Assmann, G. High Density Lipoproteins and Arteriosclerosis: Role of Cholesterol Efflux and Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, K.R. Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 51, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, J.L.; DeBose-Boyd, R.A.; Brown, M.S. Protein Sensors for Membrane Sterols. Cell 2006, 124, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, A.; Goldstein, J.L.; McDonald, J.G.; Brown, M.S. Switch-like Control of SREBP-2 Transport Triggered by Small Changes in ER Cholesterol: A Delicate Balance. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, C.; Wang, X.; Briggs, M.R.; Admon, A.; Wu, J.; Hua, X.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. SREBP-1, a Basic-Helix-Loop-Helix-Leucine Zipper Protein That Controls Transcription of the Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor Gene. Cell 1993, 75, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M.L.; Mendez, A.J.; Moore, K.J.; Andersson, L.P.; Panjeton, H.A.; Freeman, M.W. ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter A1 Contains an NH2-Terminal Signal Anchor Sequence That Translocates the Protein’s First Hydrophilic Domain to the Exoplasmic Space. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 15137–15145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oram, J.F. HDL Apolipoproteins and ABCA1: Partners in the Removal of Excess Cellular Cholesterol. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2003, 23, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, M.; Hamon, Y.; Chimini, G. The Human ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) Transporter Superfamily. J. Lipid Res. 2001, 42, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, D.W. An Atlas of Fine Structure: The Cell, Its Organelles, and Inclusions; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Farese, R.V.; Walther, T.C. Lipid Droplets Finally Get a Little R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Cell 2009, 139, 855–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschallinger, J.; Iram, T.; Zardeneta, M.; Lee, S.E.; Lehallier, B.; Haney, M.S.; Pluvinage, J.V.; Mathur, V.; Hahn, O.; Morgens, D.W.; et al. Lipid-Droplet-Accumulating Microglia Represent a Dysfunctional and Proinflammatory State in the Aging Brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, A.; Dinkel, L.; Müller, S.A.; Sebastian Monasor, L.; Schifferer, M.; Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; König, J.; Vidatic, L.; Bremova-Ertl, T.; Lieberman, A.P.; et al. Loss of NPC1 Enhances Phagocytic Uptake and Impairs Lipid Trafficking in Microglia. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanisch, U.-K.; Kettenmann, H. Microglia: Active Sensor and Versatile Effector Cells in the Normal and Pathologic Brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2007, 10, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, S.M.; Hans, E.E.; Jiang, S.; Wangler, L.M.; Godbout, J.P. Astrocyte Immunosenescence and Deficits in Interleukin 10 Signaling in the Aged Brain Disrupt the Regulation of Microglia Following Innate Immune Activation. Glia 2022, 70, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zareba, J.; Peri, F. Microglial ‘Fat Shaming’ in Development and Disease. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021, 73, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badimon, A.; Strasburger, H.J.; Ayata, P.; Chen, X.; Nair, A.; Ikegami, A.; Hwang, P.; Chan, A.T.; Graves, S.M.; Uweru, J.O.; et al. Negative Feedback Control of Neuronal Activity by Microglia. Nature 2020, 586, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmotto, M.; Monteleone, D.; Piras, A.; Valsecchi, V.; Tropiano, M.; Ariano, S.; Fornaro, M.; Vercelli, A.; Puyal, J.; Arancio, O.; et al. Aβ1-42 Monomers or Oligomers Have Different Effects on Autophagy and Apoptosis. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1827–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baerends, E.; Soud, K.; Folke, J.; Pedersen, A.-K.; Henmar, S.; Konrad, L.; Lycas, M.D.; Mori, Y.; Pakkenberg, B.; Woldbye, D.P.D.; et al. Modeling the Early Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease by Administering Intracerebroventricular Injections of Human Native Aβ Oligomers to Rats. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagno, E.; Bardini, P.; Guglielmotto, M.; Danni, O.; Tabaton, M. The Various Aggregation States of β-Amyloid 1–42 Mediate Different Effects on Oxidative Stress, Neurodegeneration, and BACE-1 Expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.J.; Jessup, W. Oxysterols: Sources, Cellular Storage and Metabolism, and New Insights into Their Roles in Cholesterol Homeostasis. Mol. Asp. Med. 2009, 30, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamba, P.; Testa, G.; Gargiulo, S.; Staurenghi, E.; Poli, G.; Leonarduzzi, G. Oxidized Cholesterol as the Driving Force behind the Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.Y.; Chavis, J.A.; Liu, L.-Z.; Drew, P.D. Cholesterol Oxides Induce Programmed Cell Death in Microglial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 249, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, C.; Teng, M.; Jiao, K.; Shen, Z.; Zhu, D.; Yue, J.; Li, Z.; et al. The ROS-Mediated Activation of IL-6/STAT3 Signaling Pathway Is Involved in the 27-Hydroxycholesterol-Induced Cellular Senescence in Nerve Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2017, 45, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.S.A.; Oliver, P.L. ROS Generation in Microglia: Understanding Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, B.N.; Schlesinger, P.H.; Baker, N.A. Perturbations of Membrane Structure by Cholesterol and Cholesterol Derivatives Are Determined by Sterol Orientation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4854–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, J.M.; Westerman, P.W.; Carey, M.C. Fluorocholesterols, in Contrast to Hydroxycholesterols, Exhibit Interfacial Properties Similar to Cholesterol. J. Lipid Res. 2000, 41, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.P.; Yoss, N.L. 25-Hydroxysterols Increase the Permeability of Liposomes to Ca2+ and Other Cations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1984, 770, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theunissen, J.J.; Jackson, R.L.; Kempen, H.J.; Demel, R.A. Membrane Properties of Oxysterols. Interfacial Orientation, Influence on Membrane Permeability and Redistribution between Membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1986, 860, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelqvist, H.; Wäster, P.; Kågedal, K.; Öllinger, K. The Lysosome: From Waste Bag to Potential Therapeutic Target. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013, 5, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosselet, F.; Saint-Pol, J.; Fenart, L. Effects of Oxysterols on the Blood–Brain Barrier: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 687–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamba, P.; Leonarduzzi, G.; Tamagno, E.; Guglielmotto, M.; Testa, G.; Sottero, B.; Gargiulo, S.; Biasi, F.; Mauro, A.; Viña, J.; et al. Interaction between 24-Hydroxycholesterol, Oxidative Stress, and Amyloid-β in Amplifying Neuronal Damage in Alzheimer’s Disease: Three Partners in Crime: 24-Hydroxycholesterol Potentiates Amyloid-Beta Neurotoxicity. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompier, D.; Vejux, A.; Zarrouk, A.; Gondcaille, C.; Geillon, F.; Nury, T.; Savary, S.; Lizard, G. Brain Peroxisomes. Biochimie 2014, 98, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nury, T.; Yammine, A.; Menetrier, F.; Zarrouk, A.; Vejux, A.; Lizard, G. 7-Ketocholesterol- and 7β-Hydroxycholesterol-Induced Peroxisomal Disorders in Glial, Microglial and Neuronal Cells: Potential Role in Neurodegeneration: 7-Ketocholesterol and 7β-Hydroxycholesterol-Induced Peroxisomal Disorders and Neurodegeneration. In Peroxisome Biology: Experimental Models, Peroxisomal Disorders and Neurological Diseases; Lizard, G., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology: London, UK; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1299, pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Diestel, A.; Aktas, O.; Hackel, D.; Häke, I.; Meier, S.; Raine, C.S.; Nitsch, R.; Zipp, F.; Ullrich, O. Activation of Microglial Poly(ADP-Ribose)-Polymerase-1 by Cholesterol Breakdown Products during Neuroinflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1729–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loving, B.A.; Tang, M.; Neal, M.C.; Gorkhali, S.; Murphy, R.; Eckel, R.H.; Bruce, K.D. Lipoprotein Lipase Regulates Microglial Lipid Droplet Accumulation. Cells 2021, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-García, M.; Rué, L.; León, T.; Julve, J.; Carbó, J.M.; Matalonga, J.; Auer, H.; Celada, A.; Escolà-Gil, J.C.; Steffensen, K.R.; et al. Reciprocal Negative Cross-Talk between Liver X Receptors (LXRs) and STAT1: Effects on IFN-γ–Induced Inflammatory Responses and LXR-Dependent Gene Expression. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 6520–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghoff, S.A.; Spieth, L.; Sun, T.; Hosang, L.; Schlaphoff, L.; Depp, C.; Düking, T.; Winchenbach, J.; Neuber, J.; Ewers, D.; et al. Microglia Facilitate Repair of Demyelinated Lesions via Post-Squalene Sterol Synthesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Račková, L. Cholesterol Load of Microglia: Contribution of Membrane Architecture Changes to Neurotoxic Power? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 537, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielska, A.; Matyjek, M.; Kwiatkowska, K. TLR4 and CD14 Trafficking and Its Influence on LPS-Induced pro-Inflammatory Signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 1233–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, X.; Cummins, D.J.; Paul, S.M. Neuroinflammation-Induced Acceleration of Amyloid Deposition in the APP V717F Transgenic Mouse: Neuroinflammation-Induced Acceleration of Amyloid Deposition. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001, 14, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, J. Lipopolysaccharide-Induced-Neuroinflammation Increases Intracellular Accumulation of Amyloid Precursor Protein and Amyloid β Peptide in APPswe Transgenic Mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003, 14, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, M.; Cao, X.; Hu, G.; Xiao, M. Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of High Cholesterol Diet on Aged Brain. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, M.T.; Nasrallah, I.M.; Wolk, D.A.; Chang, C.C.Y.; Chang, T.-Y. Cholesterol, Atherosclerosis, and APOE in Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia (VCID): Potential Mechanisms and Therapy. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 647990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famer, D.; Wahlund, L.-O.; Crisby, M. Rosuvastatin Reduces Microglia in the Brain of Wild Type and ApoE Knockout Mice on a High Cholesterol Diet, Implications for Prevention of Stroke and AD. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelopoulou, E.; Paudel, Y.N.; Papageorgiou, S.G.; Piperi, C. APOE Genotype and Alzheimer’s Disease: The Influence of Lifestyle and Environmental Factors. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 2749–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minagawa, H.; Gong, J.-S.; Jung, C.-G.; Watanabe, A.; Lund-Katz, S.; Phillips, M.C.; Saito, H.; Michikawa, M. Mechanism Underlying Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) Isoform-Dependent Lipid Efflux from Neural Cells in Culture. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009, 87, 2498–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannucci, J.; Sen, A.; Grammas, P. Isoform-Specific Effects of Apolipoprotein E on Markers of Inflammation and Toxicity in Brain Glia and Neuronal Cells In Vitro. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2021, 43, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Fitzner, D.; Bosch-Queralt, M.; Weil, M.-T.; Su, M.; Sen, P.; Ruhwedel, T.; Mitkovski, M.; Trendelenburg, G.; Lütjohann, D.; et al. Defective Cholesterol Clearance Limits Remyelination in the Aged Central Nervous System. Science 2018, 359, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchward, M.A.; Todd, K.G. Statin Treatment Affects Cytokine Release and Phagocytic Activity in Primary Cultured Microglia through Two Separable Mechanisms. Mol. Brain 2014, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, F.L.; Wang, Y.; Tom, I.; Gonzalez, L.C.; Sheng, M. TREM2 Binds to Apolipoproteins, Including APOE and CLU/APOJ, and Thereby Facilitates Uptake of Amyloid-Beta by Microglia. Neuron 2016, 91, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulland, T.K.; Colonna, M. TREM2—A Key Player in Microglial Biology and Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, A.A.; Lin, K.; van Lengerich, B.; Lianoglou, S.; Przybyla, L.; Davis, S.S.; Llapashtica, C.; Wang, J.; Kim, D.J.; Xia, D.; et al. TREM2 Regulates Microglial Cholesterol Metabolism upon Chronic Phagocytic Challenge. Neuron 2020, 105, 837–854.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oram, J.F.; Heinecke, J.W. ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter A1: A Cell Cholesterol Exporter That Protects against Cardiovascular Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1343–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasinska, J.M.; de Haan, W.; Franciosi, S.; Ruddle, P.; Fan, J.; Kruit, J.K.; Stukas, S.; Lütjohann, D.; Gutmann, D.H.; Wellington, C.L.; et al. ABCA1 Influences Neuroinflammation and Neuronal Death. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 54, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, N.; Abe-Dohmae, S.; Iwamoto, N.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; Yokoyama, S. Helical Apolipoproteins of High-Density Lipoprotein Enhance Phagocytosis by Stabilizing ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter A7. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 2591–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikawa, T.; Holm, M.-L.; Kanekiyo, T. ABCA7 and Pathogenic Pathways of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Yao, R.-M.; Mi, T.-Y.; Zhang, L.-M.; Wu, H.; Cheng, J.-B.; Li, Y.-F. Cognition-Enhancing Effect of YL-IPA08, a Potent Ligand for the Translocator Protein (18 KDa) in the 5 × FAD Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Pathology. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Choi, E.-A.; Kim, Y.-S.; Kim, Y.; You, Y.H.-S.; Han, Y.-E.; Kim, H.-S.; Bae, Y.-J.; Kim, J.; Kang, H.-T. Statin Exposure and the Risk of Dementia in Individuals with Hypercholesterolaemia. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 288, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barthold, D.; Joyce, G.; Diaz Brinton, R.; Wharton, W.; Kehoe, P.G.; Zissimopoulos, J. Association of Combination Statin and Antihypertensive Therapy with Reduced Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia Risk. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glodzik, L.; Santisteban, M.M. Blood-Brain Barrier Crossing Renin-Angiotensin System Drugs: Considerations for Dementia and Cognitive Decline. Hypertension 2021, 78, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glodzik, L.; Rusinek, H.; Kamer, A.; Pirraglia, E.; Tsui, W.; Mosconi, L.; Li, Y.; McHugh, P.; Murray, J.; Williams, S.; et al. Effects of Vascular Risk Factors, Statins, and Antihypertensive Drugs on PiB Deposition in Cognitively Normal Subjects. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2016, 2, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Zou, L.; Meng, L.; Qiang, G.; Yan, M.; Zhang, Z. Cholesterol Metabolism in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 2183–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.G.; Eckert, G.P.; Igbavboa, U.; Müller, W.E. Statins and Neuroprotection: A Prescription to Move the Field Forward. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1199, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, L.; Sheng, X.; Zheng, W.; Chu, H.; Zhang, G. Atorvastatin Attenuates Cognitive Deficits and Neuroinflammation Induced by Aβ1–42 Involving Modulation of TLR4/TRAF6/NF-ΚB Pathway. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 64, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Most, P.J.; Dolga, A.M.; Nijholt, I.M.; Luiten, P.G.M.; Eisel, U.L.M. Statins: Mechanisms of Neuroprotection. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009, 88, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewen, T.; Qiuting, L.; Chaogang, T.; Tao, T.; Jun, W.; Liming, T.; Guanghong, X. Neuroprotective Effect of Atorvastatin Involves Suppression of TNF-α and Upregulation of IL-10 in a Rat Model of Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 66, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, A.J.; Davey, A.K.; Anoopkumar-Dukie, S. Statins Reduce Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cytokine and Inflammatory Mediator Release in an In Vitro Model of Microglial-Like Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 2017, 2582745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, H.; Ghasemi, F.; Barreto, G.E.; Sathyapalan, T.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. The Effects of Statins on Microglial Cells to Protect against Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Mechanistic Review. BioFactors 2020, 46, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, C.; Crisby, M.; Winblad, B.; Schultzberg, M. Effects of Statins on Microglia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005, 82, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clementino, A.R.; Marchi, C.; Pozzoli, M.; Bernini, F.; Zimetti, F.; Sonvico, F. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Statin-Loaded Biodegradable Lecithin/Chitosan Nanoparticles: A Step Toward Nose-to-Brain Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 716380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, K.P.; Shytle, D.R.; Bai, Y.; San, N.; Zeng, J.; Freeman, M.; Mori, T.; Fernandez, F.; Morgan, D.; Sanberg, P.; et al. Lovastatin Modulation of Microglial Activation via Suppression of Functional CD40 Expression. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 78, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahan, K.; Sheikh, F.G.; Namboodiri, A.M.; Singh, I. Lovastatin and Phenylacetate Inhibit the Induction of Nitric Oxide Synthase and Cytokines in Rat Primary Astrocytes, Microglia, and Macrophages. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 2671–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaesu, G.; Kishida, S.; Hiyama, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shibuya, H.; Irie, K.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J.; Matsumoto, K. TAB2, a Novel Adaptor Protein, Mediates Activation of TAK1 MAPKKK by Linking TAK1 to TRAF6 in the IL-1 Signal Transduction Pathway. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongjun, Y.; Shuyun, H.; Lei, C.; Xiangrong, C.; Zhilin, Y.; Yiquan, K. Atorvastatin Suppresses Glioma Invasion and Migration by Reducing Microglial MT1-MMP Expression. J. Neuroimmunol. 2013, 260, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kata, D.; Földesi, I.; Feher, L.Z.; Hackler, L.; Puskas, L.G.; Gulya, K. Rosuvastatin Enhances Anti-Inflammatory and Inhibits pro-Inflammatory Functions in Cultured Microglial Cells. Neuroscience 2016, 314, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, K.; Imai, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Kohsaka, S. Microglia/Macrophage-Specific Protein Iba1 Binds to Fimbrin and Enhances Its Actin-Bundling Activity: Fimbrin as an Iba1-Interacting Molecule. J. Neurochem. 2004, 88, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirado, E.; Rajaram, M.V.S.; Chawla, A.; Daigle, J.; La Perle, K.M.D.; Arnett, E.; Turner, J.; Schlesinger, L.S. Deletion of PPARγ in Lung Macrophages Provides an Immunoprotective Response against M. Tuberculosis Infection in Mice. Tuberculosis 2018, 111, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.; Murphy, K.J.; Clarke, R.; Lynch, M.A. Atorvastatin Prevents Age-Related and Amyloid-β-Induced Microglial Activation by Blocking Interferon-γ Release from Natural Killer Cells in the Brain. J. Neuroinflamm. 2011, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.-W.; Chen, J.-Y.; Wu, P.-C.; Wu, B.-N. Atorvastatin Prevents Neuroinflammation in Chronic Constriction Injury Rats through Nuclear NFκB Downregulation in the Dorsal Root Ganglion and Spinal Cord. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamboli, I.Y.; Barth, E.; Christian, L.; Siepmann, M.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Tolksdorf, K.; Heneka, M.T.; Lütjohann, D.; Wunderlich, P.; et al. Statins Promote the Degradation of Extracellular Amyloid β-Peptide by Microglia via Stimulation of Exosome-Associated Insulin-Degrading Enzyme (IDE) Secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 37405–37414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee Yong, V.; Forsyth, P.A.; Bell, R.; Krekoski, C.A.; Edwards, D.R. Matrix Metalloproteinases and Diseases of the CNS. Trends Neurosci. 1998, 21, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagase, H.; Visse, R.; Murphy, G. Structure and Function of Matrix Metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, S.G.; Kahveci, Z. Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression in Astrocytes and Microglia in Human Oligodendroglioma and Astrocytoma. J. Mol. Histol. 2009, 40, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petanceska, S.S.; DeRosa, S.; Sharma, A.; Diaz, N.; Duff, K.; Tint, S.G.; Refolo, L.M.; Pappolla, M. Changes in Apolipoprotein E Expression in Response to Dietary and Pharmacological Modulation of Cholesterol. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2003, 20, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodero, A.O.; Barrantes, F.J. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins on Brain Cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocivavsek, A.; Rebeck, G.W. Inhibition of C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Increases ApoE Expression in Vitro and in Vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 387, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidnejad-Tosaramandani, T.; Kashanian, S.; Al-Sabri, M.H.; Kročianová, D.; Clemensson, L.E.; Gentreau, M.; Schiöth, H.B. Statins and Cognition: Modifying Factors and Possible Underlying Mechanisms. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 968039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Study Type | Model | Statin (Dose) | Outcome Measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang, 2018 [120] | In vivo | Sprague Dawley male rats (age 7 to 8 weeks), 250–300 g | Atorvastatin 5- and 10-mg/kg (chronic) | Number of Iba-1-positive microglia | Reduced number of Iba-1 positive microglia. |

| Ewen, 2013 [122] | In vivo | Sprague–Dawley male rats (12 week of age) | Atorvastatin 2, 5, and 10 mg/kg | TNF-α and IL-10 levels, and infiltration at site of injury | Atorvastatin decreased TNF-α and increased in IL-10 levels, and number of activated microglia. |

| Lindberg, 2005 [125] | In vitro and in vivo | CHME-3 human cell line; primary rat microglia | Atorvastatin 0.1, 1, 5, and 20 mM or Simvastatin 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mM; Atorvastatin 1, 5, and 20 μM | Microglial Secretion of IL-6 | Atorvastatin reduce IL-6 secretion of stimulated human and rat microglia. |

| Townsend, 2004 [127] | In vitro and in vivo | BALB/c mice microglia | Lovastatin 10 µM | IL-6, TNF-α and IL-β1 concentrations and phagocytosis activity | Lovastatin reduced IL-6, TNF-α and IL-β1 concentrations and attenuated impaired phagocytosis in primary mouse microglia. |

| Pahan, 1997 [128] | In vitro | Isolated primary rat microglia from mixed cultures | Lovastatin 10 µM | Nitiric Oxide, TNF-a, IL-1b, and IL-6 concentrations | In LPS stimulated primary rat microglia, lovastatin reduced nitric oxide, TNF- α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in supernatant. |

| Yongjun, 2013 [130] | In vitro | Primary human microglia | Atorvastatin 0.1 mM | MT1-MMP expression | Reduced microglia expression of MT1-MMP. |

| Kata, 2016 [131] | In vitro | Primary rat microglia | Rosuvastatin 1 µM | Iba-1 immunoreactivity; phagocytosis activity; IL-10, IL-1b and TNF-α production. | In microglia challenged with LPS, rosuvastatin reduced IL-1 β, TNF-α production and phagocytosis, IL-10 and Iba1 immunoreactivity was increased. |

| Chu, 2015 [135] | In vivo | Sprague–Dawley male rats | Atorvastatin 10 mg/kg/day | pNFκB immunostaining | Proinflammatory pNFκB proteins were decreased by atorvastatin in microglia, following surgery. |

| Tamboli, 2010 [136] | In vivo | BV-2 mouse microglia | Lovastatin 5 µM | Aβ degration, Westen blot | Lovastatin enhanced the degradation of extracellular Aβ by microglial cells. |

| Petanceska, 2003 [140] | In vivo | C57/BL6 mice and BV-2 cell line | Lovastatin 5 µM and atorvastatin 5 µM | ApoE Western blot | In mice, lovastatin reduced ApoE secretion. Atorvastatin reduced the levels of both cellular and secreted ApoE. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz Herrera, O.M.; Zivkovic, A.M. Microglia and Cholesterol Handling: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123105

Muñoz Herrera OM, Zivkovic AM. Microglia and Cholesterol Handling: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(12):3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123105

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz Herrera, Oscar M., and Angela M. Zivkovic. 2022. "Microglia and Cholesterol Handling: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease" Biomedicines 10, no. 12: 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123105

APA StyleMuñoz Herrera, O. M., & Zivkovic, A. M. (2022). Microglia and Cholesterol Handling: Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines, 10(12), 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10123105