The Evolving Scenario in the Assessment of Radiological Response for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Era of Immunotherapy: Strengths and Weaknesses of Surrogate Endpoints

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy

3. Clinical and Radiological Endpoints in HCC

- (1)

- Solid hard endpoints, such as OS.

- (2)

- Surrogate endpoints, such as progression-free survival (PFS), time to progression (TTP), and objective response rate (ORR).

- (3)

3.1. Hard Endpoints

3.2. Surrogate Endpoints

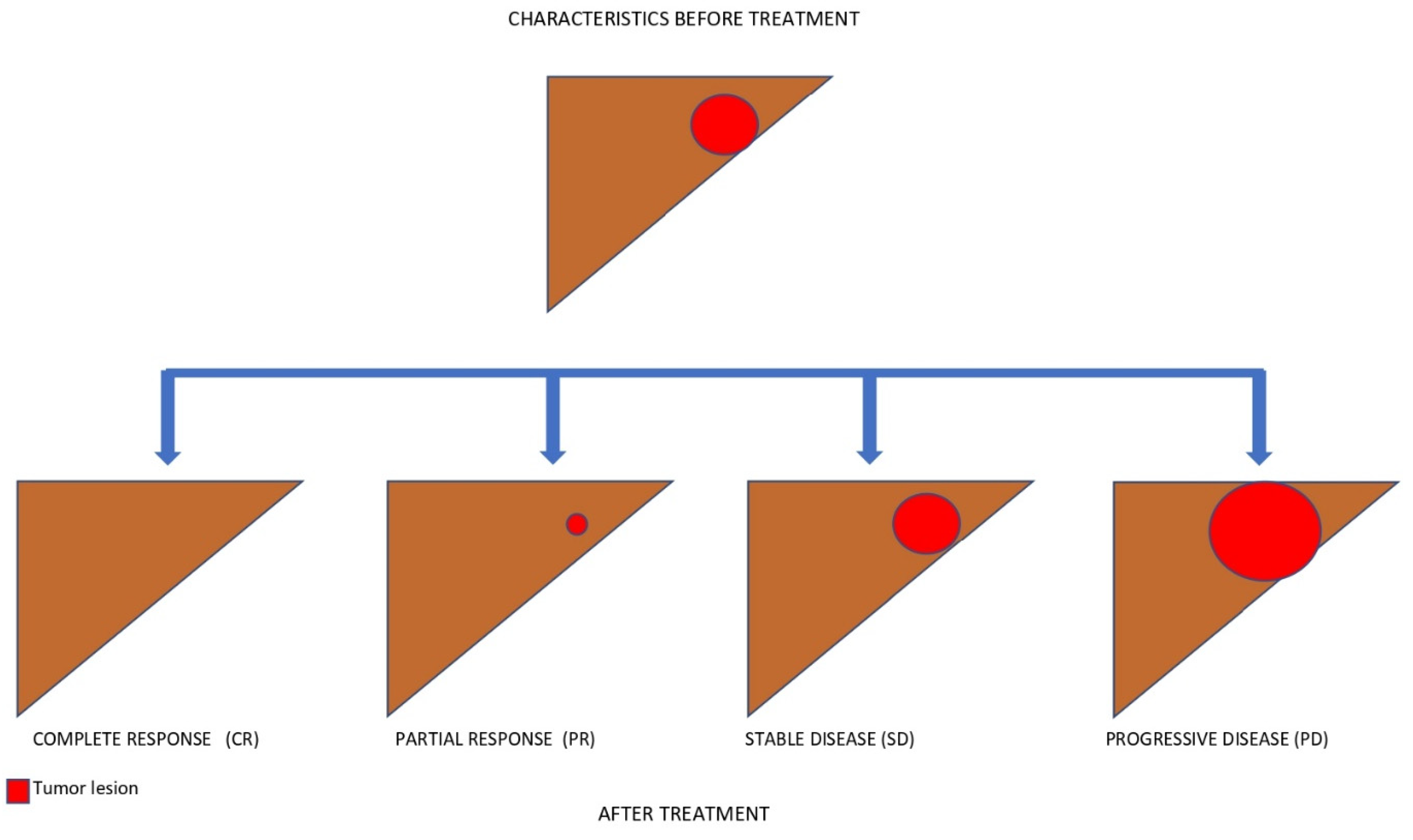

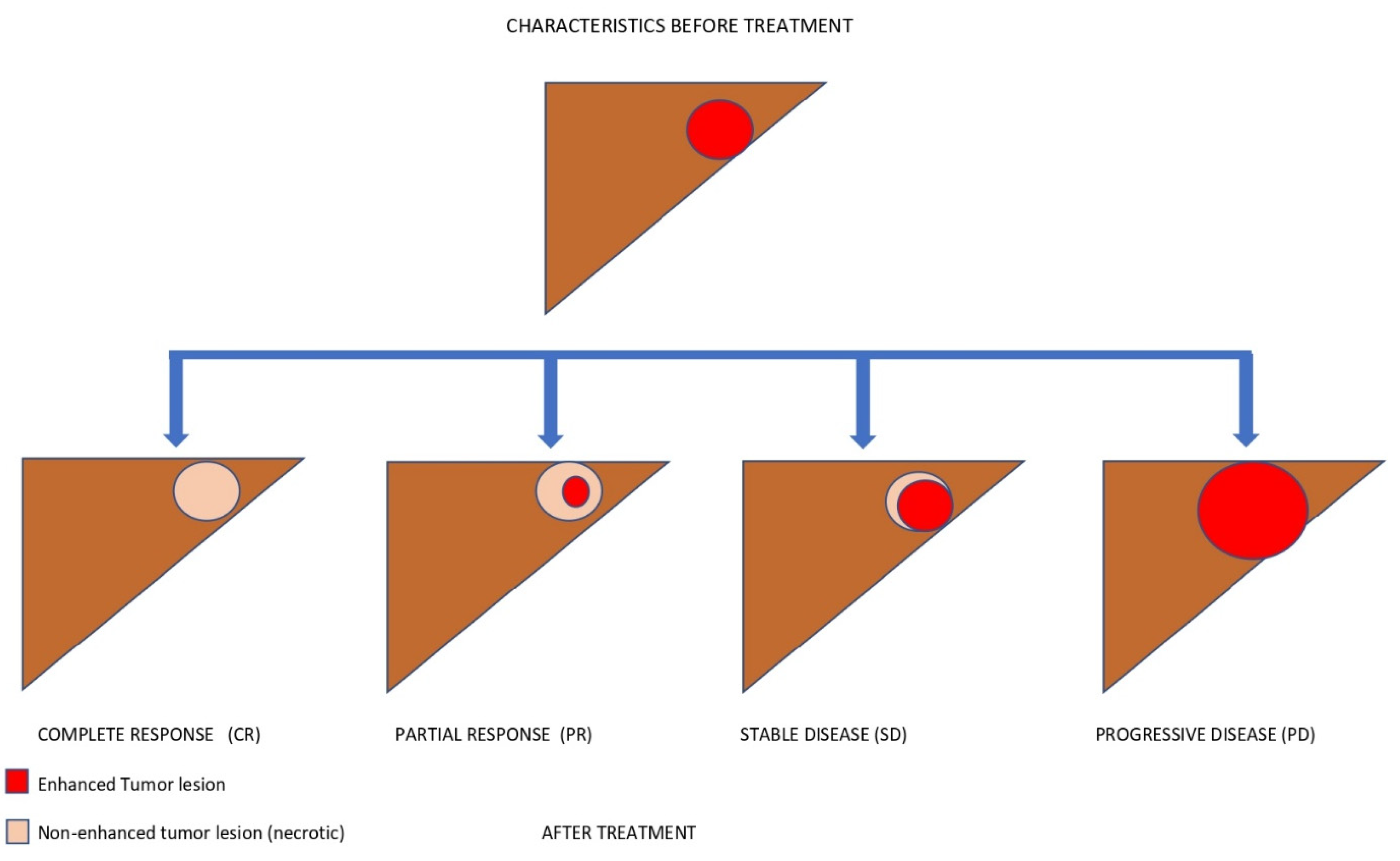

- Time-independent endpoints include objective response rate (ORR)—defined as the proportion of patients achieving complete (CR) and partial (PR) radiological responses—and disease control rate (DCR), which also includes stable disease. Radiology-based endpoints are able to capture early anticancer activity; hence, they are helpful in early-phase studies (i.e., phase I or II). A high ORR may also identify the treatments that are more suitable for downstaging purposes, meaning a stage migration toward the possibility of performing locoregional treatments. The main disadvantage of ORR and DCR is that they are not able to identify the time when the event occurs, and they are also subject to assessment bias. Indeed, the rate of radiological responses can be affected by both the subjectivity of the radiologists and the adopted radiological criteria.

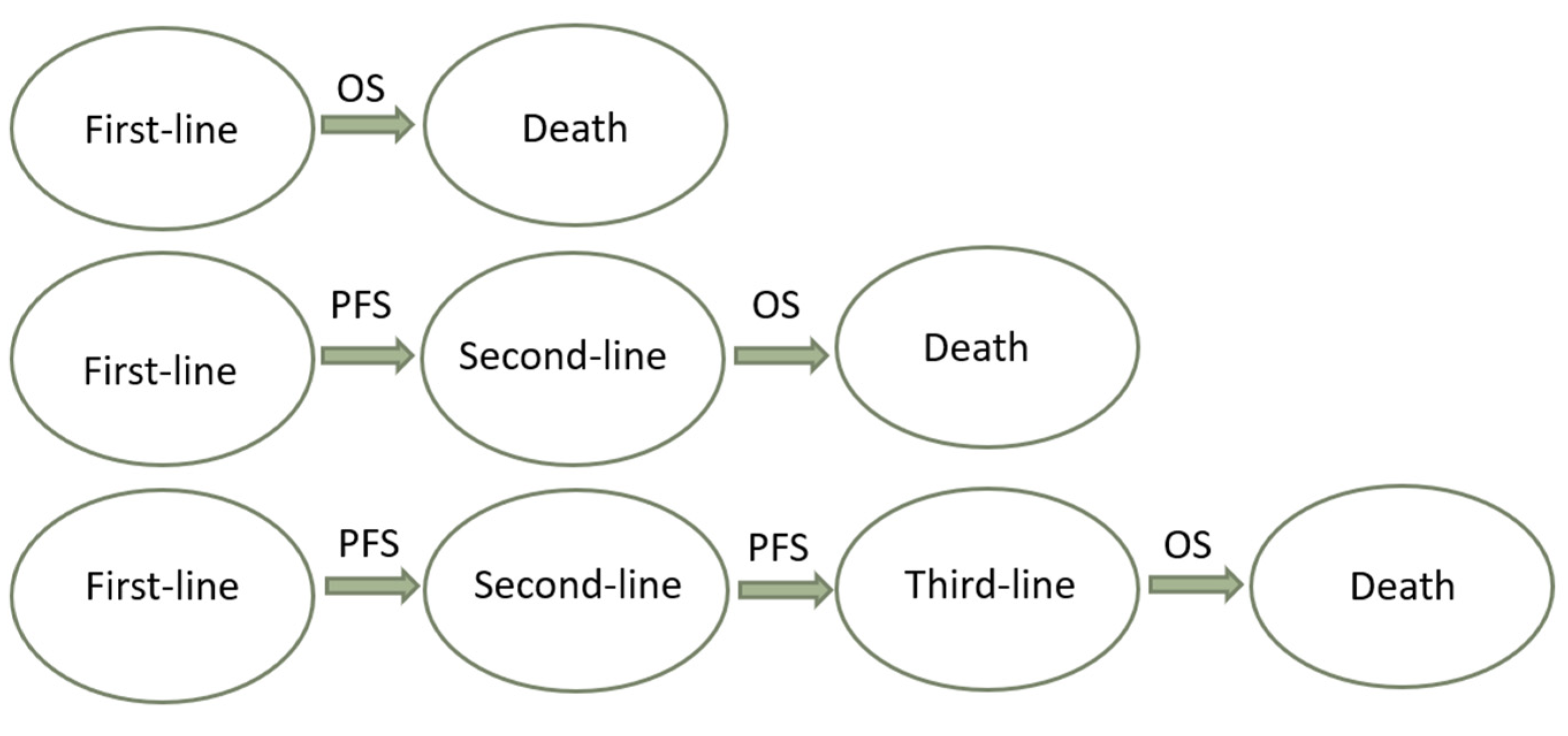

- Time-dependent surrogate endpoints include time to recurrence (TTR) and recurrence-free survival (RFS) in the setting of curative treatments, and TTP and PFS in the setting of advanced HCC. TTR and TTP are defined as the time from the start of treatment (or randomisation) to radiological recurrence or progression, respectively. TTP has been adopted as a secondary endpoint in HCC trials [14]. Although TTP is not biased by post-progression treatments and it reports the time to the event, it is unable to detect important events such as death, and it is subject to the same assessment bias as ORR [38]. RFS and PFS are composite time-dependent endpoints, often used as both primary and secondary endpoints in oncological trials. RFS is defined as the time from the start of treatment (or randomisation) to radiological recurrence or death, and it is employed in curative settings (i.e., after surgery or ablation). PFS is defined as the time from the start of treatment to radiological progression or death, and it is commonly used in the setting of systemic treatments. These are not influenced by post-recurrence or post-progression treatments and crossover bias. For these reasons, PFS could be useful to evaluate the effectiveness of sequential therapies in settings where multiple treatment lines are available. Based on this assumption, the patient’s journey could be represented as the sum of multiple subsequent PFSs of sequential treatment lines (Figure 2) [21,25,39]. The use of PFS was initially discouraged in HCC trials due to the risk of competing events and the coexistence of cancer and underlying liver disease. This problem was mitigated by including only patients with well-preserved liver function in HCC trials [40]. Overall, PFS has been used to obtain accelerated drug approval in several oncological settings [37]. It has been estimated that between 2009 and 2014, 66% of anticancer drugs approved by the FDA were approved on the basis of PFS. Most anticancer trials also use PFS as a primary endpoint, and around 50% of them have shown benefits to OS [41]. The counterpart of this phenomenon is the possibility to introduce ineffective or harmful drugs to the market, which need to be evaluated with hard endpoints in post-marketing studies [42]. For instance, a critical review of anticancer drugs approved based on PFS is crucial—not only with regard to their efficacy, but also their safety. In fact, it has been speculated that poor drug tolerance may result in imbalanced dropouts of the experimental drug, and due to informative bias this might lead to longer PFS without any improvement of OS or quality of life [38]. Time to treatment failure (TTF), defined as the time from the start of treatment to its discontinuation for any reasons (e.g., death, progression, or toxicity), has been proposed to overcome this limitation of PFS, although it is not recommended by the FDA for drug approval. This issue should be widely considered when there is no surrogacy between PFS and OS in the context of HCC, and could be particularly relevant if a competing survival event—such as hepatic decompensation with respect to tumour progression—is not usually recorded by trials [29,43]. To this end, novel endpoints aiming to measure the time to hepatic decompensation or the decompensation-free survival are needed to improve the evaluation of the net benefit of systemic treatments for HCC. To summarise, the main limitations of surrogate endpoints are the assessment bias and the need for surrogacy validation. Assessment bias might be mitigated at the trial level by using central expert radiology reviews. Validation of a surrogate endpoint is related to the ability of that endpoint to quickly and accurately predict the clinical outcome. Validation needs to be performed at both the individual and trial levels, using individual patients’ data and aggregated data, respectively [33].

3.3. Validation of Surrogacy

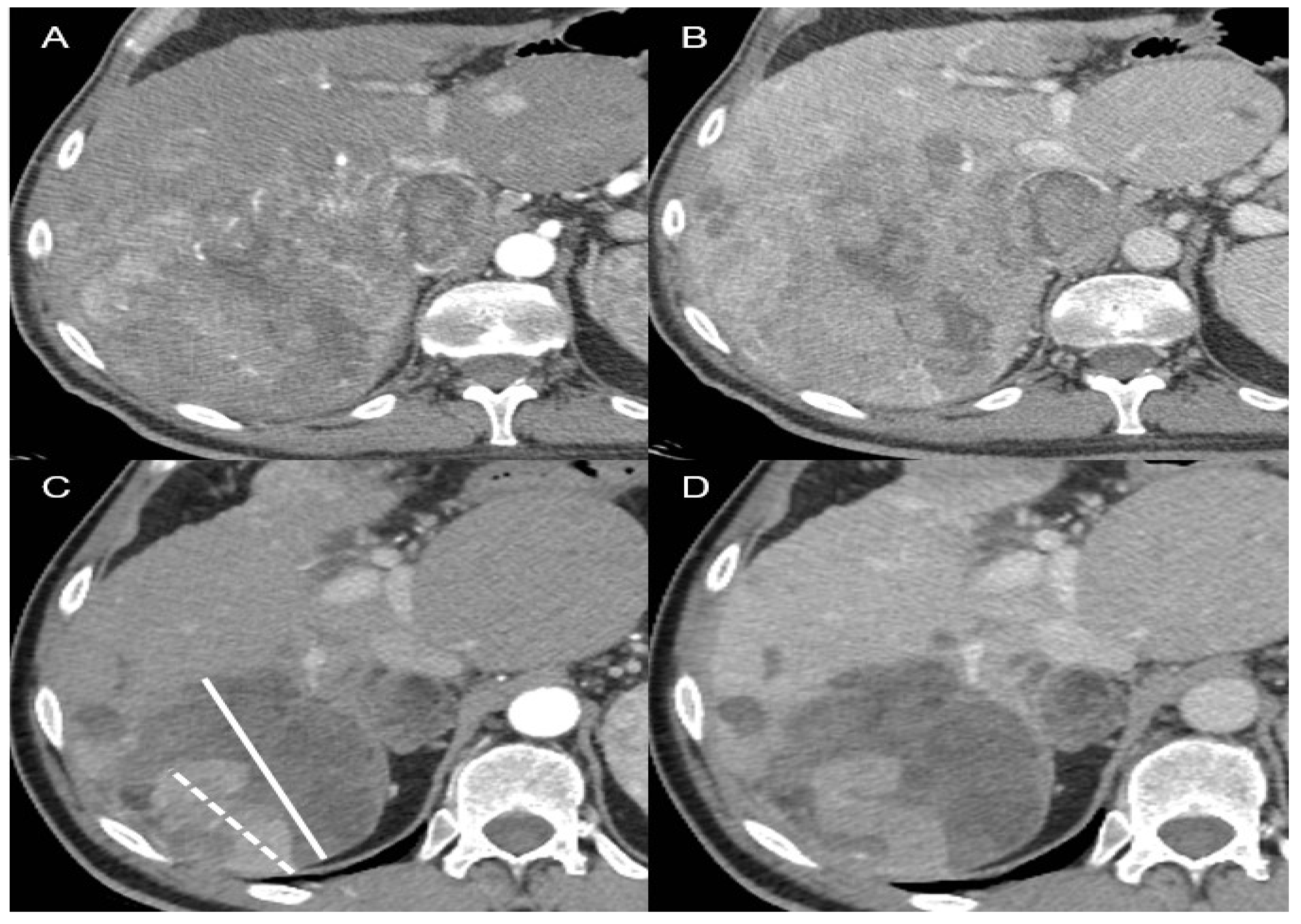

3.4. Radiology

4. The Relevance of Liver Function

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garuti, F.; Neri, A.; Avanzato, F.; Gramenzi, A.; Rampoldi, D.; Rucci, P.; Farinati, F.; Giannini, E.G.; Piscaglia, F.; Rapaccini, G.L.; et al. The changing scenario of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy: An update. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, A.; Svegliati-Baroni, G.; Ortolani, A.; Cucco, M.; Dalla Riva, G.V.; Giannini, E.G.; Piscaglia, F.; Rapaccini, G.; Di Marco, M.; Caturelli, E.; et al. Epidemiological trends and trajectories of MAFLD-associated hepatocellular carcinoma 2002–2033: The ITA.LI.CA database. Gut 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.J.H.; Setiawan, V.W.; Ng, C.H.; Lim, W.H.; Muthiah, M.D.; Tan, E.X.; Dan, Y.Y.; Roberts, L.R.; Loomba, R.; Huang, D.Q. Global Burden of Liver Cancer in Males and Females: Changing Etiological Basis and the Growing Contribution of NASH. Hepatology 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabibbo, G.; Petta, S.; Barbàra, M.; Missale, G.; Virdone, R.; Caturelli, E.; Piscaglia, F.; Morisco, F.; Colecchia, A.; Farinati, F.; et al. A meta-analysis of single HCV-untreated arm of studies evaluating outcomes after curative treatments of HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2017, 37, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, E.; Moscatelli, A.; Pellegatta, G.; Vitale, A.; Farinati, F.; Ciccarese, F.; Piscaglia, F.; Rapaccini, G.L.; Di Marco, M.; Caturelli, E.; et al. Application of the Intermediate-Stage Subclassification to Patients With Untreated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, G.; Enea, M.; Attanasio, M.; Bruix, J.; Craxi, A.; Cammà, C. A meta-analysis of survival rates of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010, 51, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, E.; Critelli, R.; Lei, B.; Marzocchi, G.; Cammà, C.; Giannelli, G.; Pontisso, P.; Cabibbo, G.; Enea, M.; Colopi, S.; et al. Neoangiogenesis-related genes are hallmarks of fast-growing hepatocellular carcinomas and worst survival. Results from a prospective study. Gut 2016, 65, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K.; Alqahtani, S.; Yopp, A.C.; Singal, A.G. Role of Multidisciplinary Care in the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2021, 41, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, G.; Latteri, F.; Antonucci, M.; Craxì, A. Multimodal approaches to the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 6, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.G.; Zhang, E.; Narasimman, M.; Rich, N.E.; Waljee, A.K.; Hoshida, Y.; Yang, J.D.; Reig, M.; Cabibbo, G.; Nahon, P.; et al. HCC surveillance improves early detection, curative treatment receipt, and survival in patients with cirrhosis: A meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, A.; Reddy, K.R. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Current treatment strategies. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2005, 8, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanbhogue, A.K.; Karnad, A.B.; Prasad, S.R. Tumor response evaluation in oncology: Current update. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2010, 34, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Ricci, S.; Mazzaferro, V.; Hilgard, P.; Gane, E.; Blanc, J.-F.; De Oliveira, A.C.; Santoro, A.; Raoul, J.-L.; Forner, A.; et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Han, K.-H.; Ikeda, K.; Piscaglia, F.; Baron, A.; Park, J.-W.; Han, G.; Jassem, J.; et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruix, J.; Qin, S.; Merle, P.; Granito, A.; Huang, Y.-H.; Bodoky, G.; Pracht, M.; Yokosuka, O.; Rosmorduc, O.; Breder, V.; et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Meyer, T.; Cheng, A.-L.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Rimassa, L.; Ryoo, B.-Y.; Cicin, I.; Merle, P.; Chen, Y.; Park, J.-W.; et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, R.K.; Rimassa, L.; Cheng, A.L.; Kaseb, A.; Qin, S.; Zhu, A.X.; Chan, S.L.; Melkadze, T.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Breder, V.; et al. Cabozantinib plus atezolizumab versus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (COSMIC-312): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 995–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig, M.; Forner, A.; Rimola, J.; Ferrer-Fàbrega, J.; Burrel, M.; Garcia-Criado, Á.; Kelley, R.K.; Galle, P.R.; Mazzaferro, V.; Salem, R.; et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J. Hepatol. 2022, 76, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

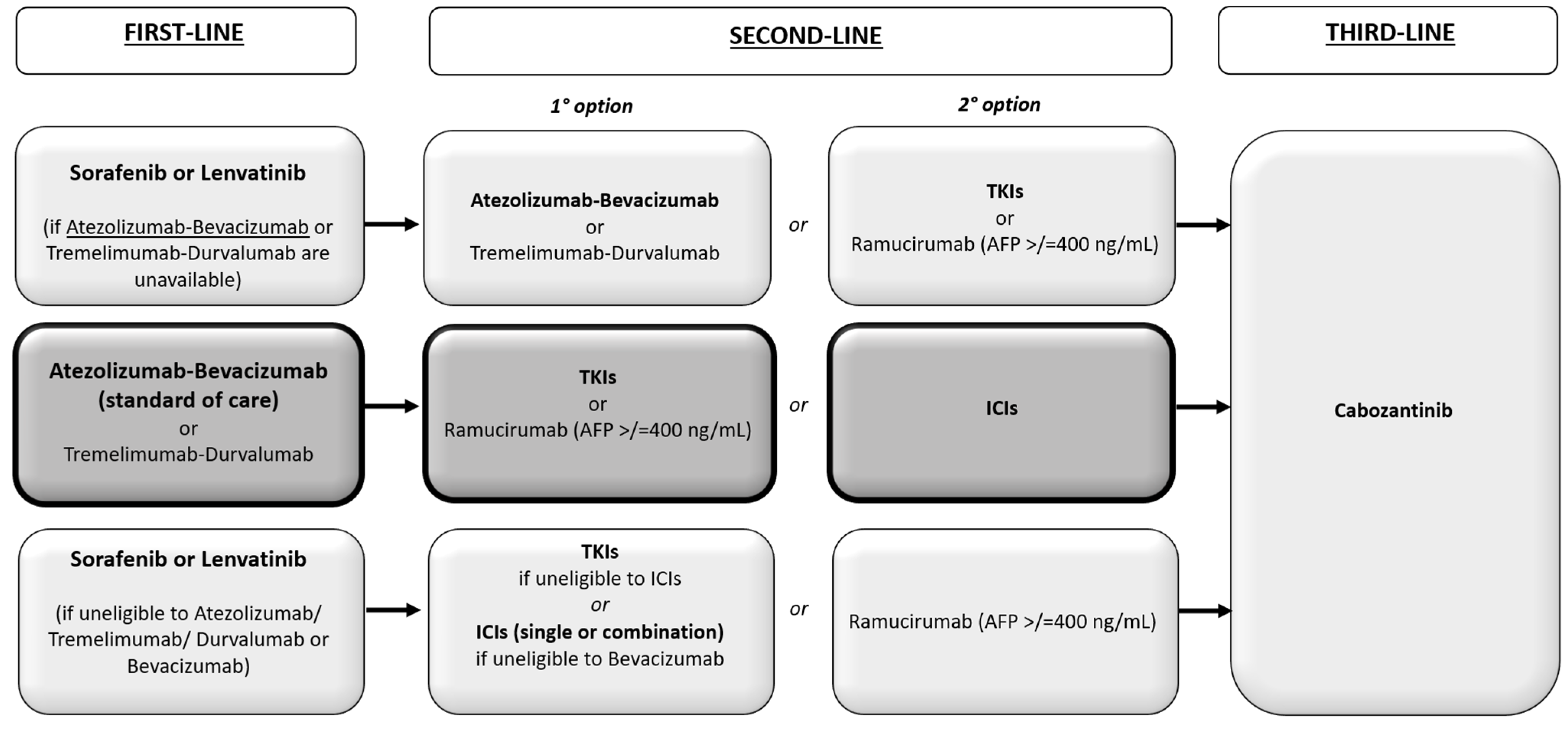

- Cabibbo, G.; Reig, M.; Celsa, C.; Torres, F.; Battaglia, S.; Enea, M.; Rizzo, G.E.M.; Petta, S.; Calvaruso, V.; Di Marco, V.; et al. First-Line Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Based Sequential Therapies for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Rationale for Future Trials. Liver Cancer 2021, 11, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovoli, F.; Renzulli, M.; Granito, A.; Golfieri, R.; Bolondi, L. Radiologic criteria of response to systemic treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatic Oncol. 2017, 4, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, S.; Toschi, L.; Castello, A.; Grizzi, F.; Mansi, L.; Lopci, E. Clinical Characteristics of Patient Selection and Imaging Predictors of Outcome in Solid Tumors Treated With Checkpoint-Inhibitors. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2017, 44, 2310–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulkey, F.; Theoret, M.R.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R.; Sridhara, R. Comparison of iRECIST Versus RECIST V.1.1 in Patients Treated With an Anti-PD-1 or PDL1 Antibody: Pooled FDA Analysis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, G.; Celsa, C.; Enea, M.; Battaglia, S.; Rizzo, G.E.M.; Grimaudo, S.; Matranga, D.; Attanasio, M.; Bruzzi, P.; Craxì, A.; et al. Optimizing Sequential Systemic Therapies for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Decision Analysis. Cancers 2020, 12, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordan, J.D.; Kennedy, E.B.; Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Beg, M.S.; Brower, S.T.; Gade, T.P.; Goff, L.; Gupta, S.; Guy, J.; Harris, W.P.; et al. Systemic Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: ASCO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 4317–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.; Martinelli, E.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: Clinicalguidelines@esmo.org; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Updated treatment recommendations for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from the ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruix, J.; Chan, S.L.; Galle, P.R.; Rimassa, L.; Sangro, B. Systemic treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: An EASL position paper. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabibbo, G.; Aghemo, A.; Lai, Q.; Masarone, M.; Montagnese, S.; Ponziani, F.R. Optimizing systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: The key role of liver function. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Montal, R.; Villanueva, A. Randomized trials and endpoints in advanced HCC: Role of PFS as a surrogate of survival. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.K.; Karakasis, K.; Oza, A.M. Outcomes and endpoints in trials of cancer treatment: The past, present, and future. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e32–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdur, R. Endpoints for assessing drug activity in clinical trials. Oncologist 2008, 13 (Suppl. 2), 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F. Surrogate End Points and Their Validation in Oncology Clinical Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1436–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celsa, C.; Giuffrida, P.; Stornello, C.; Grova, M.; Spatola, F.; Rizzo, G.E.M.; Busacca, A.; Cannella, R.; Battaglia, S.; Cammà, C.; et al. Systemic therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: The present and the future. Recent. Progress. Med. 2021, 112, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R.L. Surrogate endpoints in clinical trials: Definition and operational criteria. Stat. Med. 1989, 8, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyse, M.; Molenberghs, G.; Burzykowski, T.; Renard, D.; Geys, H. The validation of surrogate endpoints in meta-analyses of randomized experiments. Biostatistics 2000, 1, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.Y.; Joshi, S.K.; Tran, A.; Prasad, V. Estimation of Study Time Reduction Using Surrogate End Points Rather Than Overall Survival in Oncology Clinical Trials. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannock, I.F.; Pond, G.R.; Booth, C.M. Biased Evaluation in Cancer Drug Trials-How Use of Progression-Free Survival as the Primary End Point Can Mislead. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 679–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsa, C.; Cabibbo, G.; Battaglia, S.; Giuffrida, P. Efficacy and safety of Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab-based sequential treatment for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A simulation model. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, S387–S388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Di Bisceglie, A.M.; Bruix, J.; Kramer, B.S.; Lencioni, R.; Zhu, A.X.; Sherman, M.; Schwartz, M.; Lotze, M.; Talwalkar, J.; et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Paggio, J.C.; Berry, J.S.; Hopman, W.M.; Eisenhauer, E.A.; Prasad, V.; Gyawali, B.; Booth, C.M. Evolution of the randomized clinical trial in the era of precision oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyawali, B.; Kesselheim, A.S. Reinforcing the social compromise of accelerated approval. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 596–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Cabibbo, G. Antiviral therapy in the palliative setting of HCC (BCLC-B and -C). J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushti, S.L.; Mulkey, F.; Sridhara, R. Evaluation of Overall Response Rate and Progression-Free Survival as Potential Surrogate Endpoints for Overall Survival in Immunotherapy Trials. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.; Porcher, R.; Crequit, P.; Ravaud, P.; Dechartres, A. Differences in Treatment Effect Size Between Overall Survival and Progression-Free Survival in Immunotherapy Trials: A Meta-Epidemiologic Study of Trials with Results Posted at ClinicalTrials.gov. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 1686–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, G.; Celsa, C.; Enea, M.; Battaglia, S.; Rizzo, G.; Busacca, A.; Matranga, D.; Attanasio, M.; Reig, M.; Craxì, A.; et al. Progression-Free Survival Early Assessment Is a Robust Surrogate Endpoint of Overall Survival in Immunotherapy Trials of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Villanueva, A.; Marrero, J.A.; Schwartz, M.; Meyer, T.; Galle, P.R.; Lencioni, R.; Greten, T.F.; Kudo, M.; Mandrekar, S.J.; et al. Trial Design and Endpoints in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: AASLD Consensus Conference. Hepatology 2021, 73 (Suppl. 1), 158–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernán, M.A. The hazards of hazard ratios [published correction appears in Epidemiology. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Lau, G.; Kudo, M.; Chan, S.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Furuse, J.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Kang, Y.-K.; Van Dao, T.; De Toni, E.N.; et al. Tremelimumab plus Durvalumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, R.; Pilotto, S.; Caccese, M.; Grizzi, G.; Sperduti, I.; Giannarelli, D.; Milella, M.; Besse, B.; Tortora, G.; Bria, E. Do immune checkpoint inhibitors need new studies methodology? J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10 (Suppl. 13), S1564–S1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broglio, K.R.; Berry, D.A. Detecting an overall survival benefit that is derived from progression-free survival. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregson, J.; Sharples, L.; Stone, G.W.; Burman, C.F.; Öhrn, F.; Pocock, S. Nonproportional Hazards for Time-to-Event Outcomes in Clinical Trials: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 2102–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celsa, C.; Cabibbo, G.; Enea, M.; Battaglia, S.; Rizzo, G.E.M.; Busacca, A.; Giuffrida, P.; Stornello, C.; Brancatelli, G.; Cannella, R.; et al. Are radiological endpoints surrogate outcomes of overall survival in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with transarterial chemoembolization? Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.-W.; Jang, M.-J.; Lee, K.-H.; Cho, E.J.; Lee, J.-H.; Yu, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Yoon, J.-H.; Kim, T.-Y.; Han, S.-W.; et al. TTP as a surrogate endpoint in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with molecular targeted therapy: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, T.; Yamashita, T.; Toyama, T.; Arai, K.; Kawaguchi, K.; Kitamura, K.; Yamashita, T.; Sakai, Y.; Mizukoshi, E.; Honda, M.; et al. Surrogacy of Time to Progression for Overall Survival in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Systemic Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Liver Cancer 2019, 8, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucchetti, A.; Casadei Gardini, A. Understanding surrogate measures of overall survival after trans-arterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 891–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, R.; Montal, R.; Torres, F.; Park, J.-W.; Decaens, T.; Raoul, J.-L.; Kudo, M.; Chang, C.; Ríos, J.; Boige, V.; et al. Objective response by mRECIST as a predictor and potential surrogate end-point of overall survival in advanced HCC. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llovet, J.M.; Decaens, T.; Raoul, J.-L.; Boucher, E.; Kudo, M.; Chang, C.; Kang, Y.-K.; Assenat, E.; Lim, H.-Y.; Boige, V.; et al. Brivanib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who were intolerant to sorafenib or for whom sorafenib failed: Results from the randomized phase III BRISK-PS study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3509–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Montal, R.; Finn, R.S.; Castet, F.; Ueshima, K.; Nishida, N.; Haber, P.K.; Hu, Y.; Chiba, Y.; Schwartz, M.; et al. Objective Response Predicts Survival in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treated with Systemic Therapies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 3443–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montal, R.; Lencioni, R.; Llovet, J.M. Reply to: “mRECIST for systemic therapies: More evidence is required before recommendations could be made”. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lencioni, R.; Llovet, J.M. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010, 30, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Lencioni, R. mRECIST for HCC: Performance and novel refinements. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannella, R.; Lewis, S.; da Fonseca, L.; Ronot, M.; Rimola, J. Immunotherapy-Based Treatments of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2022, 29, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reig, M.; Rimola, J.; Torres, F.; Darnell, A.; Rodriguez-Lope, C.; Forner, A.; Llarch, N.; Ríos, J.; Ayuso, C.; Bruix, J. Postprogression survival of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Rationale for second-line trial design. Hepatology 2013, 58, 2023–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, T.; D’Alessio, A.; Pinter, M.; Balcar, L.; Scheiner, B.; Marron, T.; Jun, T.; Dharmapuri, S.; Ang, C.; Saeed, A.; et al. Progression pattern and therapeutic sequencing following immune checkpoint inhibition for HCC: An international observational study. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, S383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruix, J.; Sherman, M.; Llovet, J.M.; Beaugrand, M.; Lencioni, R.; Burroughs, A.K.; Christensen, E.; Pagliaro, L.; Colombo, M.; Rodés, J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J. Hepatol. 2001, 35, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Memon, K.; Miller, F.H.; Nikolaidis, P.; Kulik, L.M.; Lewandowski, R.J.; Ryu, R.K.; Sato, K.T.; Gates, V.; Mulcahy, M.F.; et al. Role of the EASL, RECIST, and WHO response guidelines alone or in combination for hepatocellular carcinoma: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. J. Hepatol. 2011, 54, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Ikeda, M.; Ueshima, K.; Sakamoto, M.; Shiina, S.; Tateishi, R.; Nouso, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Furuse, J.; Miyayama, S.; et al. Response Evaluation Criteria in Cancer of the liver version 6 (Response Evaluation Criteria in Cancer of the Liver 2021 revised version). Hepatol. Res. 2022, 52, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, L.; Bogaerts, J.; Perrone, A.; Ford, R.; Schwartz, L.H.; Mandrekar, S.; Lin, N.U.; Litière, S.; Dancey, J.; Chen, A.; et al. iRECIST: Guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, e143–e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannella, R.; Cammà, C.; Matteini, F.; Celsa, C.; Giuffrida, P.; Enea, M.; Comelli, A.; Stefano, A.; Cammà, C.; Midiri, M.; et al. Radiomics Analysis on Gadoxetate Disodium-Enhanced MRI Predicts Response to Transarterial Embolization in Patients with HCC. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, H.J.; Spivey, J.R.; Hanish, S.I.; El-Rayes, B.F.; Kauh, J.S.; Chen, Z.; Kim, H.S. mRECIST and EASL responses at early time point by contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI predict survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treated by doxorubicin drug-eluting beads transarterial chemoembolization (DEB TACE). Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillmore, R.; Stuart, S.; Kirkwood, A.; Hameeduddin, A.; Woodward, N.; Burroughs, A.K.; Meyer, T. EASL and mRECIST responses are independent prognostic factors for survival in hepatocellular cancer patients treated with transarterial embolization. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 1309–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincenzi, B.; Di Maio, M.; Silletta, M.; D’Onofrio, L.; Spoto, C.; Piccirillo, M.C.; Daniele, G.; Comito, F.; Maci, E.; Bronte, G.; et al. Prognostic relevance of objective response according to EASL Criteria and mRECIST criteria in hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with loco-regional therapies: A literature-based meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.-L.; Kang, Y.-K.; Chen, Z.; Tsao, C.-J.; Qin, S.; Kim, J.S.; Luo, R.; Feng, J.; Ye, S.; Yang, T.-S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeline, J.; Boucher, E.; Rolland, Y.; Vauléon, E.; Pracht, M.; Perrin, C.; Le Roux, C.; Raoul, J.-L. Comparison of tumor response by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and modified RECIST in patients treated with sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2012, 118, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, S.; Kanai, F.; Ooka, Y.; Motoyama, T.; Suzuki, E.; Tawada, A.; Chiba, T.; Yokosuka, O. Initial response to sorafenib by using enhancement criteria in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Int. 2013, 7, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, J.; Hidaka, H.; Nakazawa, T.; Kondo, M.; Numata, K.; Tanaka, K.; Matsunaga, K.; Okuse, C.; Kobayashi, S.; Morimoto, M.; et al. Modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors is superior to response evaluation criteria in solid tumors for assessment of responses to sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Han, K.-H.; Ikeda, K.; Cheng, A.-L.; Piscaglia, F.; Ueshima, K.; Aikata, H.; Vogel, A.; et al. Analysis of survival and objective response (OR) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a phase III study of lenvatinib (REFLECT). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, V.; Iavarone, M.; Di Costanzo, G.G.; Marra, F.; Lonardi, S.; Tamburini, E.; Piscaglia, F.; Masi, G.; Celsa, C.; Foschi, F.G.; et al. Real-Life Clinical Data of Lenvatinib versus Sorafenib for Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Italy. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 9379–9389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M. Extremely High Objective Response Rate of Lenvatinib: Its Clinical Relevance and Changing the Treatment Paradigm in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Liver Cancer 2018, 7, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadei-Gardini, A.; Rimini, M.; Kudo, M.; Shimose, S.; Tada, T.; Suda, G.; Goh, M.J.; Jefremow, A.; Scartozzi, M.; Cabibbo, G.; et al. Real Life Study of Lenvatinib Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: RELEVANT Study. Liver Cancer 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Han, K.H.; Ikeda, K.; Cheng, A.L. Overall survival and objective response in advanced unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: 3 A subanalysis of the REFLECT study. J. Hepatol. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, G.; Bruix, J. Radiological endpoints as surrogates for survival benefit in Hepatocellular Carcinoma trials: All that glitters is not gold. J. Hepatol. 2022; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Park, J.-W.; Finn, R.S.; Cheng, A.-L.; Mathurin, P.; Edeline, J.; Kudo, M.; Harding, J.J.; Merle, P.; Rosmorduc, O.; et al. Nivolumab versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 459): A randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.X.; Kang, Y.-K.; Yen, C.-J.; Finn, R.S.; Galle, P.R.; Llovet, J.M.; Assenat, E.; Brandi, G.; Pracht, M.; Lim, H.Y.; et al. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Sangro, B.; Yau, T.; Crocenzi, T.S.; Kudo, M.; Hsu, C.; Kim, T.-Y.; Choo, S.-P.; Trojan, J.; Welling, T.H., 3rd; et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): An open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Ryoo, B.-Y.; Merle, P.; Kudo, M.; Bouattour, M.; Lim, H.Y.; Breder, V.; Edeline, J.; Chao, Y.; Ogasawara, S.; et al. Pembrolizumab As Second-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Kang, Y.-K.; Kim, T.-Y.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Santoro, A.; Sangro, B.; Melero, I.; Kudo, M.; Hou, M.-M.; Matilla, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Previously Treated With Sorafenib: The CheckMate 040 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, e204564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabibbo, G.; Celsa, C.; Calvaruso, V.; Petta, S.; Cacciola, I.; Cannavò, M.R.; Madonia, S.; Rossi, M.; Magro, B.; Rini, F.; et al. Direct-acting antivirals after successful treatment of early hepatocellular carcinoma improve survival in HCV-cirrhotic patients. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsa, C.; Stornello, C.; Giuffrida, P.; Giacchetto, C.M.; Grova, M.; Rancatore, G.; Pitrone, C.; Di Marco, V.; Cammà, C.; Cabibbo, G. Direct-acting antiviral agents and risk of Hepatocellular carcinoma: Critical appraisal of the evidence. Ann. Hepatol. 2022, 27 (Suppl. 1), 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapena, V.; Enea, M.; Torres, F.; Celsa, C.; Rios, J.; Rizzo, G.E.M.; Nahon, P.; Mariño, Z.; Tateishi, R.; Minami, T.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after direct-acting antiviral therapy: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Gut 2022, 71, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampertico, P.; Invernizzi, F.; Viganò, M.; Loglio, A.; Mangia, G.; Facchetti, F.; Primignani, M.; Jovani, M.; Iavarone, M.; Fraquelli, M.; et al. The long-term benefits of nucleos(t)ide analogs in compensated HBV cirrhotic patients with no or small esophageal varices: A 12-year prospective cohort study. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papatheodoridis, G.V.; Sypsa, V.; Dalekos, G.; Yurdaydin, C.; van Boemmel, F.; Buti, M.; Goulis, J.; Calleja, J.L.; Chi, H.; Manolakopoulos, S.; et al. Eight-year survival in chronic hepatitis B patients under long-term entecavir or tenofovir therapy is similar to the general population. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennisi, G.; Celsa, C.; Enea, M.; Vaccaro, M.; Di Marco, V.; Ciccioli, C.; Infantino, G.; La Mantia, C.; Parisi, S.; Vernuccio, F.; et al. Effect of pharmacological interventions and placebo on liver Histology in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A network meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 2279–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iavarone, M.; Cabibbo, G.; Piscaglia, F.; Zavaglia, C.; Grieco, A.; Villa, E.; Cammà, C.; Colombo, M.; SOFIA (SOraFenib Italian Assessment) Study Group. Field-practice study of sorafenib therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective multicenter study in Italy. Hepatology 2011, 54, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Endpoint | Definition | Characteristics | Pros | Cons | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard Endpoints | OS | Time between random trial allocation and death from any cause | All regular FDA drug approvals for advanced HCC were based upon improvements in OS | Most robust endpoint in advanced HCC | Increasing number of effective therapies after progression → need for surrogate endpoints | |

| Surrogate Endpoints | ORR | The percentage of patients who achieve an objective tumour response | ORR, assessed by sensitive criteria, in single-arm phase II trials could be a useful tool to prioritise treatments for testing in phase III trials | The definition of duration of stable disease varies between studies |

| |

| TTP | The time between trial allocation and radiological progression, usually defined by standard criteria such as RECIST or mRECIST | Symmetric repeated radiological measurements every 6–8 weeks are required to avoid missing moderate differences between treatment groups | A moderate correlation has been established between PFS and OS | Not all types of tumour progression necessarily have the same clinical meaning (e.g., new extrahepatic/intrahepatic lesions, vascular invasion, growth of pre-existing lesions) | ||

| PFS | PFS is a composite endpoint of two variables—death, and evidence of radiological progression—usually defined by standard criteria such as RECIST or mRECIST | A moderate correlation has been established between PFS and OS | Competing risk of dying due to progressed liver dysfunction despite a relevant antitumor benefit | |||

| Parameters | Measurements of Lesions | Evaluated Parameters | Target Lesions (Max Number—Total) | Target Lesions (Max Number—per Organ) | Definition of CR | Definition of PR | Definition of PD | Definition of SD | Lymph Nodes | Criteria for Defining New Lesions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECIST 1.1 | Unidimensional | Total dimensions | 5 | 2 | Disappearance of all target lesions | ≥30% decrease in the sum of diameters of target lesions | ≥20% increase in the sum of diameters of target lesions | Any cases that do not qualify for either partial response or progressive disease | Considered as target lesions if short axis ≥15 mm | Unequivocal appearance |

| mRECIST | Unidimensional | Enhanced tumour | 5 | 2 | Disappearance of any intratumoral arterial enhancement in all target lesions | ≥30% decrease in the sum of diameters of enhancing target lesions | ≥20% in the sum of the diameters of enhancing target lesions | Any cases that do not qualify for either partial response or progressive disease | Porta hepatis lymph nodes: short axis ≥20 mm, all other locations ≥15 mm | Unequivocal appearance and typical HCC pattern |

| irRECIST | Unidimensional | Total dimensions | No change from RECIST 1.1 | No change from RECIST 1.1 | Resolution of all lesions, confirmed >4 weeks | Decrease of >30% in tumour burden in the absence of any new lesion or progression of non-target lesions | iUPD: Increase of > 20% in tumour burden from nadir; progression of NT lesions, or new lesions. iCPD: the imaging assessment performed 4–8 weeks after iUPD, confirms additional new lesions, further increase in previous new lesion size, or further increase in existing target or non-target lesions from iUPD | Clinical stability is considered when deciding whether treatment is continued after iUPD | No change from RECIST 1.1 | to the same as in RECIST 1.1, but recorded separately and not included in the sum of lesions for target lesions identified at baseline |

| Trial | Treatment Arms | Patients (n) | ORR mRECIST (%) | ORR RECIST (%) | PFS mRECIST (Months) | PFS RECIST (Months) | TTP mRECIST (Months) | TTP RECIST (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Line | ||||||||

| SHARP [14] | Sorafenib | 299 | - | 2.3 | - | - | - | 5.5 |

| Placebo | 303 | - | 0.7 | - | - | - | 2.8 | |

| REFLECT [15] | Sorafenib | 476 | 9.2 | 6.5 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Lenvatinib | 478 | 24.1 | 18.8 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 7.4 | |

| IMBRAVE 150 [18] | Atezolizumab–bevacizumab | 326 | 33.2 | 27.3 | - | 6.8 | - | - |

| Sorafenib | 159 | 13.3 | 12 | - | 4.3 | - | - | |

| HIMALAYA [49] | Durvalumab–tremelimumab (STRIDE) | 393 | - | 20 | - | 3.8 | - | 5.4 |

| Durvalumab | 389 | - | 17 | - | 3.6 | - | 3.8 | |

| Sorafenib | 389 | - | 5 | - | 4 | - | 5.6 | |

| COSMIC 312 [19] | Cabozantinib–atezolizumab | 432 | - | 11 | - | 6.8 | - | 7 |

| Sorafenib | 217 | - | 4 | - | 4.2 | - | 4.6 | |

| Cabozantinib | 188 | - | 6 | - | 5.8 | - | 6.8 | |

| Checkmate 459 [85] | Nivolumab | 371 | - | 15 | - | 3.7 | - | 3.8 |

| Sorafenib | 372 | - | 7 | - | 3.8 | - | 3.9 | |

| Second Line | ||||||||

| RESORCE [16] | Regorafenib | 379 | 11 | 7 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.9 |

| Placebo | 194 | 4 | 3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | |

| CELESTIAL [17] | Cabozantinib | 470 | - | 4 | - | 5.2 | - | 5.4 |

| Placebo | 237 | - | 0.4 | - | 1.9 | - | 1.9 | |

| REACH-2 [86] | Ramucirumab | 197 | - | 5 | - | 2.8 | - | 3 |

| Placebo | 95 | - | 1 | - | 1.6 | - | 1.6 | |

| Checkmate -040 [87] | Nivolumab | 214 | - | 20 | - | 4 | - | - |

| Keynote 240 [88] | Pembrolizumab | 278 | - | 18.3 | - | 3 | - | 3.8 |

| Placebo | 135 | - | 4.4 | - | 2.8 | - | 2.8 | |

| Checkmate 040 [89] | Nivolumab–ipilimumab (arm A) | 50 | - | 32 | - | - | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giuffrida, P.; Celsa, C.; Antonucci, M.; Peri, M.; Grassini, M.V.; Rancatore, G.; Giacchetto, C.M.; Cannella, R.; Incorvaia, L.; Corsini, L.R.; et al. The Evolving Scenario in the Assessment of Radiological Response for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Era of Immunotherapy: Strengths and Weaknesses of Surrogate Endpoints. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112827

Giuffrida P, Celsa C, Antonucci M, Peri M, Grassini MV, Rancatore G, Giacchetto CM, Cannella R, Incorvaia L, Corsini LR, et al. The Evolving Scenario in the Assessment of Radiological Response for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Era of Immunotherapy: Strengths and Weaknesses of Surrogate Endpoints. Biomedicines. 2022; 10(11):2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112827

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiuffrida, Paolo, Ciro Celsa, Michela Antonucci, Marta Peri, Maria Vittoria Grassini, Gabriele Rancatore, Carmelo Marco Giacchetto, Roberto Cannella, Lorena Incorvaia, Lidia Rita Corsini, and et al. 2022. "The Evolving Scenario in the Assessment of Radiological Response for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Era of Immunotherapy: Strengths and Weaknesses of Surrogate Endpoints" Biomedicines 10, no. 11: 2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112827

APA StyleGiuffrida, P., Celsa, C., Antonucci, M., Peri, M., Grassini, M. V., Rancatore, G., Giacchetto, C. M., Cannella, R., Incorvaia, L., Corsini, L. R., Morana, P., La Mantia, C., Badalamenti, G., Brancatelli, G., Cammà, C., & Cabibbo, G. (2022). The Evolving Scenario in the Assessment of Radiological Response for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in the Era of Immunotherapy: Strengths and Weaknesses of Surrogate Endpoints. Biomedicines, 10(11), 2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10112827