Abstract

Campylobacteriosis is an internationally important foodborne disease caused by Campylobacter jejuni. The bacterium is prevalent in chicken meat and it is estimated that as much as 90% of chicken meat on the market may be contaminated with the bacterium. The current gold standard for the detection of C. jejuni is the culturing method, which takes at least 48 h to confirm the presence of the bacterium. Hence, the aim of this work was to investigate the development of a Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) sensor platform for C. jejuni detection. Bacterial strains were cultivated in-house and used in the development of the sensor. SPR sensor chips were first functionalized with polyclonal antibodies raised against C. jejuni using covalent attachment. The gold chips were then applied for the direct detection of C. jejuni. The assay conditions were then optimized and the sensor used for C. jejuni detection, achieving a detection limit of 8 × 106 CFU·mL−1. The sensitivity of the assay was further enhanced to 4 × 104 CFU·mL−1 through the deployment of a sandwich assay format using the same polyclonal antibody. The LOD obtained in the sandwich assay was higher than that achieved using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (106–107 CFU·mL−1). This indicate that the SPR-based sandwich sensor method has an excellent potential to replace ELISA tests for C. jejuni detection. Specificity studies performed with Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, demonstrated the high specific of the sensor for C. jejuni.

1. Introduction

Campylobacter spp. are a major cause of gastroenteritis in humans and have led to economic losses by decreasing the productivity and requiring additional medical costs in developed and developing countries. Foodborne illness causes significant economic losses globally. The largest outbreak of Campylobacter was in 1978 in Bennington (VT, USA) where approximately 3000 people were infected through contaminated water [1]. In the UK, there were 72,571 confirmed cases in 2012 but the available statistics suggest more cases than these. Underreporting is estimated to occur in these instances since the disease do not require urgent hospitalization upon infection [2]. Poultry-based food forms the largest pool of C. jejuni [3]. The bacterium itself is a largely zoonotic and does not usually reproduce in foods [4]. The host, in which it colonizes, ranges from wild birds to domestic animals [5,6]. In most cases, the bacterium multiplies in chicken and the animal become a reservoir of the pathogen [7]. Campylobacter especially C. jejuni colonizes well in chicken since the microaerophilic conditions of chicken’s intestine and its body temperature (41–42 °C) are the optimum conditions for the growth of this bacterium [8]. Intestinal colonization is the main source of contamination of the final product and is usually rampant in many poultry processing plants [5]. In the past three decades, Campylobacter spp. are the focus of numerous research groups in the world. Routine food monitoring, screening, and identification of the bacteria require reliable and rapid diagnostic methods, and this has been recognized as major objective in order to reduce the impact of these pathogenic bacteria on the human and animal’s health [9].

The gold standard for the detection of C. jejuni in food products is the culturing method, which takes more than 48 h to get results. Food products such as poultry are usually consumed a few days after the production, and research on the potentially rapid detection methods using new technologies such as quartz crystal microbalance (QCM), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is intensely being conducted. Among these techniques, biosensors (SPR and QCM) have been considered as fast, easily applicable and sensitive methods for the detection of C. jejuni [10,11,12]. Of all of the biosensor methods developed for pathogen detection, optical-based methods including SPR have become the most dominant method over the years followed by the electrochemical and acoustic-based methods. SPR has been investigated for the detection of C. jejuni using antibody-based bioreceptors. Although both monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies have been used, the polyclonal antibodies have been reported to be the dominant form of antibody utilized in several works [9,10,12]. Advantages of SPR over the other methods include shorter detection time, reliable and reproducible results. However, sensitivity is an issue due to the limited evanescent wave penetration depth in SPR, particularly in the case of studying a large size pathogen as C. jejuni [12].

The SPR biosensor is a well-established unique sensing platform widely employed for a large number of analytes’ detection including bacteria. In SPR measurement of an analyte, the ligand or bioreceptor is initially immobilized on the sensor surface, and then the analyte passes through a microfluidic channel over the ligand. The direct interaction between the analyte and ligand gives rise to a measurable signal, which is detected and quantified. Since SPR is very sensitive to the refractive index of the solution, it is important to obtain a stable baseline prior to the interaction between ligand and analyte [13]. In conventional SPR, the interaction between the analyte and the sensor surface results in a rapid adsorption leading to an initial increase in the SPR angle (association phase) followed by a saturation of the surface (dissociation phase) observed as the emergence of a plateau in the sensorgram. The final stage involved the replacement (regeneration phase) of the analyte or biomolecule with buffer to remove loosely bound materials and regenerate the surface [12]. To date, the detection of C. jejuni via SPR only utilize a direct assay format, and other formats such as sandwich assay and sandwich assay with nanomaterial amplification have not been attempted, although these formats have been successful in improving bacterial detection in the other immunosensor works such as electrochemical [14] and QCM [10]. In this study, several potentially rapid assay formats were investigated, and the improvements for the detection of C. jejuni were explored which include direct, sandwich and nanomaterial-modified sandwich assays.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Rabbit polyclonal antibody against C. jejuni was obtained from the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI), Malaysia. Mouse IgG was from a commercial source (Abcam Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK). N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) were sourced from Thermo Scientific, Paisley, UK. 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUDA), 40 nm gold colloidal (AuNPs), sodium acetate, ethanolamine hydrochloride, PBS (phosphate buffered saline tablet: 0.0027 M potassium chloride, 10 mM phosphate buffer and 0.137 M sodium chloride, pH 7.4), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), Tween-20, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and ethanol were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich, Dorset, UK.

2.2. Instrumentation

A fully automated SPR-4 biosensor (Sierra Sensors GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) with its amine coated gold sensor chips was employed in this study. The instrument can carry out four separate assays simultaneously as it is equipped with four sensing spots. SPR-4 data were analyzed with the R2 software from Sierra Sensors (Hamburg, Germany) and Microsoft Excel.

2.3. Bacterial Strains and Preparation of C. jejuni Cells

MacConkey sorbitol agar, Xylose lysine deoxycholate agar (XLD) and Oxford medium were used for the enumeration of E. coli O157:H7, S. Typhimurium and L. monocytogenes, respectively, and were purchased from Acumedia Manufacturers Inc. (Baltimore, MD, USA). Campylobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni ATCC® 33291 was purchased from Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, UK. Other bacteria such as Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella Typhimurium and E. coli O157:H7 were used to verify the selectivity of the developed C. jejuni sensor, and were sourced from the culture collection of MARDI. The growth, maintenance and preparation of heat-killed C. jejuni for biosensing works are carried out as before [10].

2.4. Sensor Chip Preparation and SAM Formation

The gold surface of SPR chip needs to be cleaned prior to SAM formation. The surface was cleaned using a piranha solution (H2SO4:H2O2/3:1) [15]. Briefly, the sensor chip was initially washed with deionized water. This was followed by a second wash with ethanol. Finally, the chip was dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. A glass pipette was utilized to deposit the piranha solution over the entire sensor surface and the solution was left on the chip for 20 min. The sensor chip was then washed thrice with deionized water. Finally, the chip was rinsed with absolute ethanol. This was followed by an immersion of the sensor chip in 20 mM solution of thiol (11-MUDA) dissolved in absolute ethanol. The chip was left at ambient temperature overnight to ensure a complete formation of the carboxy-terminated thiol layer [15]. Before use, the sensor chip was rinsed with ethanol followed by deionized water, and then finally dried using nitrogen gas. MUDA coated chip can be used immediately, or stored at 4 °C in a container sealed with parafilm until further use.

2.5. Surface Activation and Antibody Immobilization

The experiment was started by docking an SPR sensor chip onto the SPR-4 instrument. A filtered and degassed PBS was utilized to prime the instrument at a constant flow rate of 25 μL·min−1. PBS buffer was also utilized as the running buffer throughout the study. Priming was carried out until a stable baseline was achieved. A 1:1 mixture of 100 mM NHS and 400 mM EDC, prepared fresh in deionized water, was injected (3 min at a flow rate of 25 μL·min−1) across the sensor surfaces to activate the surface. The mixture converts the carboxylic terminal groups of self-assembled monolayer (SAM) into the active ester of NHS [16]. Immediately, the different concentrations of rabbit polyclonal antibody against C. jejuni (50, 70, 100 and 150 µg·mL−1) were injected (3 min at a flow rate of 25 μL·min−1) on the parallel spots to determine the optimum concentration of the surface antibody. The antibody was prepared in sodium acetate buffer (100 mM, pH 5.0). Once the optimal conditions of the capture antibody for C. jejuni assay was determined, a 70 µg·mL−1 of the control (mouse IgG) and capture antibodies were injected (3 min at a flow rate of 25 μL·min−1) onto separate sensor spots. Blocking of non-specific binding on both sensor spots was achieved by an injection of 50 μg·mL−1 of BSA in PBS (3 min at a flow rate of 25 μL·min−1). Finally, unreacted NHS esters were capped with 1 M ethanolamine, pH 8.5 (a 3 min injection at a flow rate of 25 μL·min−1) [17]. A 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1 of C. jejuni cells were then injected over the sensor surface for 3 min (75 µL) to measure the optimal interaction resulting in the highest sensor response.

2.6. Optimization of C. jejuni Detection

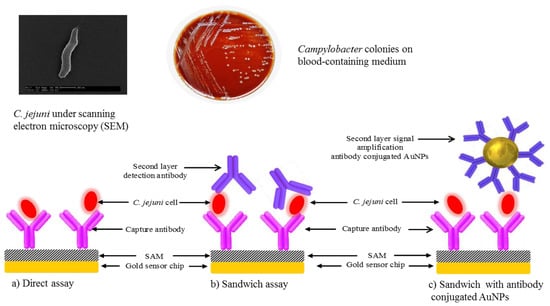

This study reports on three different assays formats: direct, sandwich and sandwich assay with antibody-functionalized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) (see Scheme 1). In the direct detection assay, C. jejuni cells at various concentrations from 1 × 104 to 1 × 109 Colony Forming Unit (CFU) mL−1 were injected over sensor surfaces functionalized with mouse IgG on the control channel and C. jejuni capture polyclonal antibody on the active channel. After C. jejuni binding, a regeneration solution consisting of 100 mM HCl (1 min, 25 μL) was injected over the surface to regenerate and reuse the surface. The regeneration solution was also injected before a sandwich assay was performed. The mild regeneration conditions coupled with a short contact time regenerated the surface, and at the same time allowing for the preservation of the biological activity of the ligand.

Scheme 1.

C. jejuni detection using three different assays formats: (a) direct; (b) sandwich and (c) sandwich assay with antibody-functionalized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs).

In the sandwich detection assay, injections of C. jejuni cells to the sensor surface via the C. jejuni capture polyclonal antibody (active channel) and over mouse IgG functionalized sensor surfaces (control channel) were carried out as before. The calibration curve was prepared by injecting various concentrations of C. jejuni cell suspensions (1 × 104 to 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1) for 3 min to allow binding interactions (75 μL). At each concentration of C. jejuni tested, an injection of 75 μL of polyclonal antibody (30 μg·mL−1) for 3 min was carried out as the detector antibody to allow binding.

2.7. Modification of AuNPs with Anti-C. jejuni Detection Antibody

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) is often used in a further amplification of signal obtained from a sandwich assay. Therefore, AuNPs were also investigated in this study. These nanomaterials are available as a colloidal gold solution and can be used directly. The method described previously [10] was utilized to prepare the antibody-colloidal gold conjugate.

2.8. Antibody-Modified AuNPs Sandwich Detection Assay for C. jejuni

The antibody-conjugated AuNPs stock in PBS was first diluted 20 times and this dilution was utilized throughout the study. C. jejuni cells were first captured by the immobilized polyclonal antibody (active channel). The sandwich detection assay started with a 75 μL injection of antibody-conjugated AuNPs to allow binding. After the binding response was obtained the surface, which was immobilized with polyclonal antibody, was regenerated with a solution of 100 mM HCl (1 min, 25 μL). Different concentrations of C. jejuni cell suspensions (1 × 104 to 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1) were injected for 3 min (75 μL) each to construct the bacterial calibration curve, and the regeneration solution was injected after each binding interaction occurred.

2.9. Specificity Studies

The developed immunosensor assay (sandwich assay) was tested for its specificity against C. jejuni. For this, binding response of non-specific bacteria, a Gram-positive bacterium (Listeria monocytogenes) and two Gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella Typhimurium), were investigated. The negative control of this experiment was PBS. A 75 µL of cell suspension of each different bacterium (1 × 109 CFU·mL−1) was injected on the sensor surface which was immobilized with C.jejuni specific surface antibody. After a binding response was obtained, the antibody immobilized surface was regenerated using HCI (100 mM) injection for 1 min.

2.10. Limit of Detection and Statistical Analysis

The limit of detection (LOD) and statistical analysis was determined using GraphPad Prism version 5.0. A Student’s t-test was utilized for comparison of means between two groups while a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc analysis was utilized for comparison between more than two groups. A p value of <0.05 was deemed statistically significant. C. jejuni standard curves were fitted to a four-parameter logistic equation [18] as follow:

where y is the response signal obtained (RU), a and d the maximum and minimum signal response (RU) of calibration curve respectively, c is the concentration of bacterial cells (log CFU·mL−1) that produces a 50% signal response (EC50) value, x is the bacterial cell concentration (log CFU·mL−1), and b is the slope-like parameter (Hill coefficient). The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated as the mean value of absorbance at a blank concentration of bacteria at three standard deviations (SD). LOD and regression analysis were calculated using the four-parameter logistics model available from PRISM non-linear regression analysis software from www.graphpad.com.

3. Results and Discussion

The advantages of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) spectroscopy are numerous including rapid, label-free, sensitive detection as well as providing real-time data. In medical diagnosis, the demand on SPR biosensors is growing since these systems allow researchers to obtain vital parameters such as specificity, binding kinetics, affinity and analyte levels. In SPR, the analyte binding to the ligand immobilized surface leads to changes in the refractive index of the dielectric; therefore, this analog signal is turned into a readable digital signal. Surface plasmon excitation-based detection of analyte consists of three methods including an optical fibre-based architecture, waveguide-based approaches, and prism-based configuration. In optical-fibre or waveguide based methods, an excitation of surface plasmons by a broadband light source takes place. The transmitted light is analyzed for a dip in the spectrum that represents resonance change.

The prism-based configuration is the subject of the current study. In this configuration, the resonance change due to the analyte-ligand interaction is monitored by amassing the light reflected as a function of the incident wavelength at a fixed angle or as a function of the incidence angle at a fixed wavelength.

3.1. Immobilization of the Antibody on SAM

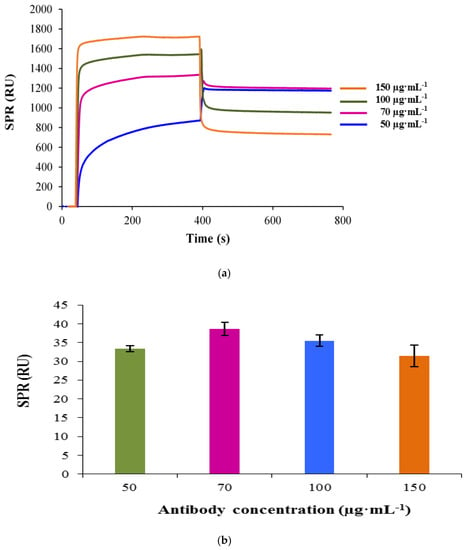

Antibody immobilization on the sensor surface must be optimized as it has a pivotal role in the development of an efficient immunoassay method [17]. Therefore, different concentrations of the capture antibody (50, 70, 100 and 150 µg·mL−1) were investigated on the sensor surface using a standard concentration of bacterial cells (1 × 107 CFU·mL−1). The changes in response unit by increasing concentrations of polyclonal antibody immobilized on the SPR sensor chip are shown in Figure 1a, while their corresponding binding responses for a fixed concentration of C. jejuni at 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1 are shown in Figure 1b. The most optimal polyclonal antibody concentration was 70 μg·mL−1, which gave the highest signal response for both antibody immobilization (1196 RU) and the bacterial capture (38.66 RU). It was discovered that higher concentrations of the polyclonal antibody did not lead to further increase in signal. In addition, the analyte binding and immobilization level were decreased, possibly due to steric hindrance. Furthermore, high concentrations of the antibody could also promote nonspecific adsorption and increase the cost of the test [19]. Hence, the polyclonal antibody concentration of 70 μg·mL−1 was chosen for further sensor studies.

Figure 1.

Concentration dependent sensorgram of the capture antibody immobilization. Mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUDA)-coated surface of gold sensor chip was activated with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide-N-hydroxysuccinimide (EDC-NHS) prior to the antibody immobilization. Four different concentrations of the capture antibody (50, 70, 100 and 150 µg·mL−1) were investigated (a). The binding responses obtained for 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1 of C. jejuni based on the varying concentration of the capture antibody immobilized on the sensor surface. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation of triplicates (b).

3.2. Optimization of C. jejuni Binding Assay

Three different assay formats for C. jejuni detection were investigated and utilized in this study: direct assay (1), sandwich assay (2) and gold-nanoparticles (AuNPs) based signal amplification assay using conjugated detector antibodies (3).

3.2.1. Direct Assay

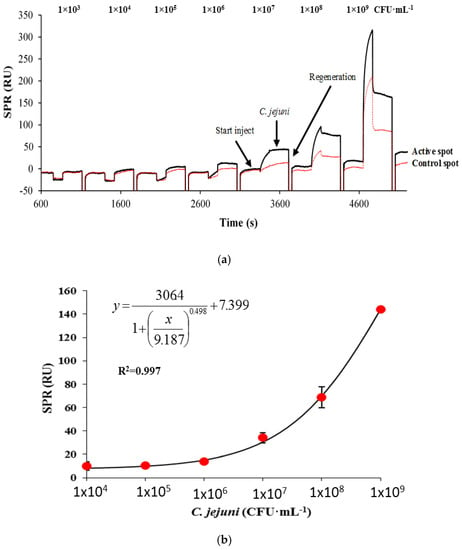

In this assay, the polyclonal antibody against C. jejuni was first immobilized on the surface as the capturing antibody. Various concentrations of C. jejuni cells were then injected onto the ligand and the binding responses were recorded as response unit (RU). The real-time sensorgram showed a gradual increase in the response with the raising concentration of C. jejuni in the calibration range from 1 × 104 to 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1 (Figure 2a). There was no increase in binding response observed at C. jejuni concentrations from 1 × 104 to 1 × 105 CFU·mL−1; however, there was a slight increase in the binding response observed (9.9 RU) at C. jejuni concentration of 1 × 106 CFU·mL−1. The increase in response unit plotted against C. jejuni concentrations showed a partial sigmoidal profile (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

The SPR sensorgram showing the binding response of C. jejuni in a direct assay format ranging from 1 × 103 to 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1 prepared in PBS buffer injected (3 min) onto 70 µg·mL−1 of capture antibody (a), and the corresponding standard curve for the direct assay (b). The surface was regenerated by 100 mM HCl after every injection of C. jejuni. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation of triplicates.

The highest response obtained was at 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1 with a binding response of 144.34 RU. The calculated LOD value was 8 × 106 CFU·mL−1 (with PBS injection as a control). The value of the LOD was poor compared to the LOD value obtained in a previous work for C. jejuni detection on a QCM instrument with a LOD value of 1 × 105 CFU·mL−1 using a direct format [10]. Generally, as far as pathogen detection is concerned, QCM instrument is more sensitive than SPR, due to the latter limited evanescent wave penetration depth. LOD values of between 103 and 107 CFU·mL−1 are reported for SPR-based assays of pathogens, while LOD values of between 101 to 103 CFU·mL−1 are reported for QCM- or piezoelectric-based assays, all in a direct format. For an instance, Son et al. [20] reported a LOD value of 105 CFU mL−1 for detecting S. enteritidis in chicken samples, while Meeusen et al. [21] reported a LOD value of 107 CFU mL-1 for both E. coli O157:H7 and S. Typhimurium [21]. A QCM-based direct detection method for Escherichia coli O157:H7 reported a LOD value of 10 cells [22], in a piezoelectric-excited millimeter-size cantilever (PEMC) while Salam et al. [23], reported a direct detection of S. Typhimurium with a LOD value of 20 cells in a Sierra sensor QCM. Another QCM-based direct detection assay for S. Typhimurium reported a LOD value of 102 [24].

3.2.2. Sandwich Assay

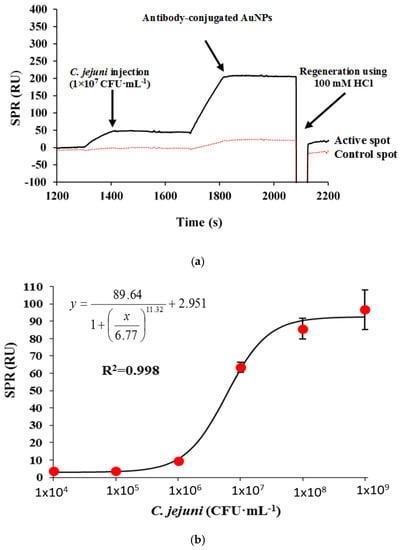

Several researchers have reported an improvement of LOD [25] or an improvement of the detection range in a sandwich format compared to a direct format [26]. Hence, the detection sensitivity of the assay using a sandwich approach was investigated. The results in Figure 3a show the real–time binding sensorgram of the sandwich assay for 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1 on the capture antibody (70 µg·mL−1), and control mouse IgG (70 µg·mL−1) immobilized surfaces, followed by the injection of optimized detection antibody (30 µg·mL−1) for 3 min. The regeneration of the sensor surface was also successful (100 mM HCl, 1 min injection) judging by the binding response that returned to the baseline after regeneration. The standard calibration curve for C. jejuni in a sandwich format over the entire calibration range from 1 × 104 to 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1 is shown in Figure 3b. There was an increase in binding response observed at C. jejuni concentration as low as 4 × 104 CFU·mL−1. The increase in response unitplotted against C. jejuni concentrations showed a sigmoidal profile. The highest response obtained was at 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1 with a binding response of 131.5 RU, with a calculated LOD value of 4 × 104 CFU·mL−1 and a good correlation coefficient value of 0.997. This is a significant improvement over the direct format observed previously with a LOD of 8 × 106 CFU·mL−1. The LOD achieved in the SPR assay was similar to the LOD value obtained in the QCM instrument with a LOD value of 2 × 104 CFU·mL−1 using a sandwich format [10]. This assay was two to three orders of magnitude sensitive compared to the available commercial ELISA kits that range from 106 to 107 CFU·mL−1 [27].

Figure 3.

The surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensorgram showing the binding response of 1 × 107 CFU mL−1 C. jejuni on the target (black line) and control surfaces (red line) followed by an injection of the detector antibody in a sandwich assay format (a), and the corresponding C. jejuni standard curve ranging from 1 × 104 to 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation of triplicates (b). (The same concentration (70 µg·mL−1) of the surface antibody was used for the immobilization of target (C. jejuni specific antibody) and control (mouse IgG antibody) antibodies).

In this work, the LOD value for the detection of C. jejuni in a direct format with a polyclonal as the capturing antibody was 8 × 106 CFU·mL−1 while a sandwich format using a polyclonal as the capturing and secondary antibodies resulted in an improvement of LOD to 4 × 104 CFU·mL−1. On the other hand, the development of a sandwich assay format for SPR demonstrates mixed results with several researchers reporting no increase in LOD using a direct or sandwich format [28]. While several researchers reported either an improvement of LOD [25], as similarly reported in this work, or improvement of the detection range with the transition from a direct into a sandwich format [26]. Other researchers, who used SPR for assaying bacterial pathogens, only report a detection in a direct format without reporting on a sandwich format, and all mentioned on the limited penetration depth of the evanescent wave as a problem for sensitive detection of bacterial pathogen in SPR-based assay methods [12,20]. Interestingly, in one report where the sandwich format gave a more sensitive LOD than a direct assay, the authors suggested that portion of the secondary antibody used can bind to the bacterial cells in areas that are within the penetration depth of the evanescent wavelengths especially near the area of the capture antibody. The authors gave this as the reason for the observed improvement of LOD in the sandwich assay seen in a particular study [25].

Direct detection format shows a higher LOD value compared to a sandwich or nanoparticles enhanced formats. For example, in the detection of S. Typhimurium in chicken meat sample, a 105 CFU·mL−1 LOD value was obtained with a direct format while the use of anti-Salmonella-magnetic beads as a marker for signal amplification resulted in an improvement of the LOD to 102 CFU·mL−1 [24]. In another example, the detection of L. monocytogenes via a piezoelectric cantilever shows a LOD of 103 CFU·mL−1 in a direct format whilst a sandwich format improves the LOD to 102 CFU·mL−1 [29].

The LOD obtained using this format was comparatively less sensitive than a direct format reported by Wei et al. [12], at 103 CFU·mL−1. However, the SPR-based direct format method reported by them showed very high cross-reactivity (about 70%) to S. Typhimurium when challenged with the bacterium at 106 CFU·mL−1. Despite this general observation, the fact that a sandwich assay can improve the detection of bacteria on an SPR suggests that this format should be included in any SPR-based methods for the detection of bacterial pathogens.

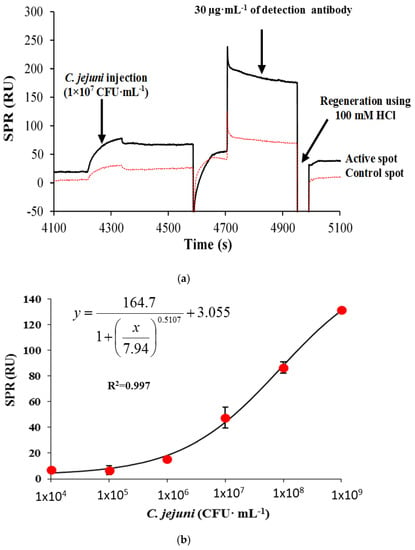

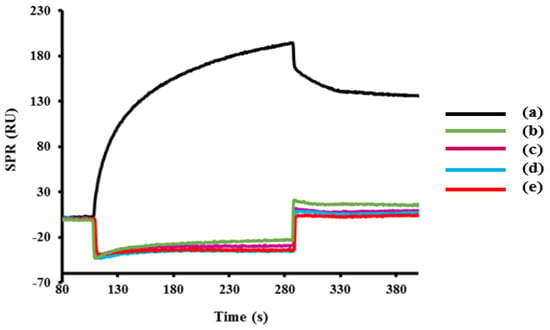

3.2.3. Sandwich Assay with Signal Amplification Using AuNPs

A further possible signal enhancement method for the C. jejuni detection on the SPR-4 sensor device was employed through the application of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) conjugated secondary antibody. The antibody-conjugated AuNPs were injected over the captured bacteria increase the refractive index, thus the binding response. A 20 times dilution of the antibody-conjugated AuNPs stock in PBS was utilized throughout the entire C. jejuni binding assay. The time of the assay for each C. jejuni concentration test was about 9 min. Figure 4a shows the resulting response obtained from a 3 min injection of 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1 C. jejuni cells followed by the injection of 20 times dilution of the antibody-AuNPs conjugate. Moreover, the regeneration of the sensor surface could be successfully achieved which allowed reusing the same surface for subsequent analysis.

Figure 4.

The SPR sensorgram showing the binding response of 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1 C. jejuni on the target (C. jejuni antibody) and control (mouse IgG antibody) antibody immobilized surfaces, followed by an injection of AuNP conjugated detector antibody for signal amplification assay using nanomaterials (a). The corresponding C. jejuni standard curve ranging from 1 × 104 to 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation of triplicates (b).

The standard calibration curve for C. jejuni in a sandwich format is shown in Figure 4b. The increase in response unit plotted against C. jejuni concentrations showed a sigmoidal profile. There was no increase in binding responses observed at C. jejuni concentrations from 1 × 104 to 1 × 105 CFU·mL−1. A slight increase in binding response was only observed at 1 × 106 CFU·mL−1 (9.33 RU). The highest response obtained was at 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1 with a binding response of 96.6 RU, with a calculated LOD value of 8 × 105 CFU·mL−1 and an acceptable correlation coefficient value of 0.998.

The sandwich immunoassay with signal amplification is more sensitive than the direct format observed previously. However, the LOD value is one order of magnitude less sensitive than a sandwich format without signal amplification AuNPs (Table 1). The value of the LOD was about three orders of magnitude less sensitive compared to the LOD value obtained previously in the QCM instrument for C. jejuni detection with a LOD value of 150 CFU·mL−1 using a sandwich format with AuNPs amplification [10]. The results indicate that the use of signal amplification using antibody-conjugated AuNPs did not improve the sensitivity of the sandwich format. The sensor surface could be regenerated for more than 10 times with about only 5.0% decrease in the surface activity from the first to the last binding cycle.

Table 1.

Limit of detection (LOD) values for various assay formats.

Comparison with other bacterial pathogen detection on an SPR platform (Table 2) shows that the method is comparable in sensitivity to other bacterial pathogen but was less sensitive than Singh et al. [30] who reported a LOD value of 1 × 102 CFU mL−1 for C. jejuni. However, Singh et al. [30] uses a C. jejuni bacteriophage for the detection of the bacterium in a direct format and to date commercialization using this type of bioreceptor is not widely available. In addition, there is no cross-reactivity work in their studies.

Table 2.

Comparison of LOD values on SPR for various bacterial pathogen.

The use of nanomaterials in signal enhancement for the detection of an analyte in SPR has been intensely studied. Most commonly applied nanomaterials include latex nanoparticles [38], metallic nanoparticles e.g., gold and silver nanoparticles [39,40], magnetic nanoparticles [41,42], carbon-based nanostructures e.g., graphene [40,43] and liposome nanoparticles [41,44]. However, the use of the above nanoparticles in the enhancement of SPR-based assays of biological materials are predominantly for protein and small molecules. Only a few number of reports are available on the use of nanoparticles for the enhancement of SPR-based detection of bacteria. SPR-based detection of bacteria is limited by the short penetration depth of the evanescent wave. In addition, the similar refractive index of most bacteria to the running buffer in SPR presents a problem for sensitive detection [25]. However, the reason the sandwich assay alone without signal amplification is more sensitive than the sandwich assay with signal amplification in this work could be due to stearic hindrance, which may cause lower signal.

3.3. Cross-Reactivity Studies Against Other Bacteria

Cross-reactivity is an important aspect of the developed immunosensor in detecting targeted bacterial pathogen in the presence of other pathogens. Thus, the specificity of the sandwich immunosensor for the detection of C. jejuni was investigated using three different foodborne pathogens including E. coli, L. monocytogenes, and S. Typhimurium. The lowest binding was exhibited by Escherichia coli with 5.3% of cross-reactivity, whilst the highest was S. Typhimurium with 10.4% cross-reactivity (Figure 5). The specificity analysis demonstrated that the developed method is suitable for routine monitoring of C. jejuni in samples containing other bacterial pathogens.

Figure 5.

The SPR sensorgram of cross-reactivity analysis showing the binding response of C. jejuni compared with other foodborne bacteria (E. coli, L. monocytogenes, S. Typhimurium) and also negative control (PBS) using the sandwich assay format. The concentration of all bacteria was fixed at 1 × 109 CFU·mL−1 and the percentage of the cross-reactivity is shown below. The surface was immobilized with C. jejuni specific antibody.

The preparation and batch of antibody used dictates the results of cross-reactivity tests [45]. The detection of C. jejuni in other methods developed for the detection of pathogen in various methods such as ELISA, electrochemical and QCM shows varying cross-reactivity results. For example, in an indirect ELISA assay for C. jejuni by Hochel et al. [46] a polyclonal antibody preparation using heat-killed antigen from C. jejuni O:23 shows little cross-reaction (<10%) to other bacterial genus including E. coli, S. Typhimurium, S. enteritidis, Yersinia pestis, Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus cereus. A SPR-based method for the detection of this bacterium showed very high cross-reactivity to S. Typhimurium (about 70%) in the concentration of 106 CFU·mL−1 [12]. Therefore, our work has shown superiority over all other existing methods for C. jejuni detection in terms of high specificity.

4. Conclusions

In this study, three different immunoassays (direct, sandwich and sandwich with AuNPs amplification) were developed for the detection of C. jejuni on an SPR device. The best assay was the sandwich, and the poorest was the direct assay. The detection limit obtained for the detection of C. jejuni cells using the sandwich assay was 4 × 104 CFU·mL−1. In addition, the comprehensive cross-reactivity investigations against the other foodborne pathogens demonstrated a very little non-specific binding and the developed assay is the most specific among the existing methods. The improvement of sensitivity over the direct method displayed the feasibility of the sandwich assay to be employed as a rapid method for the detection of C. jejuni.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and thank the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) for funding this research project.

Author Contributions

Noor Azlina Masdor performed all the experimental work and wrote the paper draft; Zeynep Altintas assisted in the laboratory work supervision; Ibtisam E. Tothill1 supervised and directed the research and finalised the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| 11-MUDA | 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid |

| CFU | Colony forming unit |

| EDC | 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| AuNPs | Gold colloidal |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| NHS | N-hydroxysuccinimide |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| QCM | Quartz crystal microbalance |

| RU | Response unit |

| SAM | Self-assembled monolayer |

| SD | Standard deviations |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

References

- Walker, R.I.; Caldwell, M.B.; Lee, E.C. Pathophysiology of Campylobacter enteritis. Microbiol. Rev. 1986, 50, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedman, C.; Neimann, J.; Wegener, H.; Tauxe, R.V. Epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni infections in the United States and other industrialized nations. In Campylobacter; Nachamkin, I., Blaser, M.J., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Vandeplas, S.; Dubois Dauphin, R.; Beckers, Y.; Thonart, P.; Théwis, A. Salmonella in chicken: Current and developing strategies to reduce contamination at farm level. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphrey, T.; O’Brien, S.; Madsen, M. Campylobacters as zoonotic pathogens: A food production perspective. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 117, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hänninen, M.-L.; Haajanen, H.; Pummi, T.; Wermundsen, K.; Katila, M.-L.; Sarkkinen, H.; Miettinen, I.; Rautelin, H. Detection and typing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli and analysis of indicator organisms in three waterborne outbreaks in Finland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenraad, P.M.F.J.; Rombouts, F.M.; Notermans, S.H.W. Epidemiological aspects of thermophilic Campylobacter in water-related environments: A review. Water Environ. Res. 1997, 69, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA—European Food Safety Authority. Scientific opinion on quantification of the risk posed by broiler meat to human Campylobacteriosis in the EU. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1437–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, H.; Murphy, G.A.; Kempf, I. Campylobacter jejuni: Public health hazards and potential control methods in poultry: A review. Vet. Med. (Praha) 2004, 49, 441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzabal, O.A.; Battie, C. Immunological methods for the detection of Campylobacter spp.—Current applications and potential use in biosensors. In Trends in Immunolabelled and Related Techniques; Abuelzein, E., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Masdor, N.A.; Altintas, Z.; Tothill, I.E. Sensitive detection of Campylobacter jejuni using nanoparticles enhanced QCM sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 78, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonjoch, X.; Calvó, L.; Soler, M.; Ruiz-Rueda, O.; Garcia-Gil, L.J. A new multiplexed real-time PCR assay to detect Campylobacter jejuni, C. coli, C. lari, and C. upsaliensis. Food Anal. Methods 2010, 3, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Oyarzabal, O.A.; Huang, T.-S.; Balasubramanian, S.; Sista, S.; Simonian, A.L. Development of a surface plasmon resonance biosensor for the identification of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Microbiol. Methods 2007, 69, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schasfoort, R.B.M.; Tudos, A.J. Handbook of Surface Plasmon Resonance; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Yang, G.; Meng, W.; Wu, L.; Zhu, A.; Jiao, X. An electrochemical impedimetric immunosensor for label-free detection of Campylobacter jejuni in diarrhea patients’ stool based on O-carboxymethylchitosan surface modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 25, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawula, M.; Altintas, Z.; Tothill, I.E. SPR detection of cardiac troponin T for acute myocardial infarction. Talanta 2016, 146, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altintas, Z.; Uludag, Y.; Gurbuz, Y.; Tothill, I. Development of surface chemistry for surface plasmon resonance based sensors for the detection of proteins and DNA molecules. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 712, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altintas, Z.; Uludag, Y.; Gurbuz, Y.; Tothill, I.E. Surface plasmon resonance based immunosensor for the detection of the cancer biomarker carcinoembryonic antigen. Talanta 2011, 86, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpinski, K.F. Optimality assessment in the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Biometrics 1990, 46, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchatip, S.; Ananthanawat, C.; Sithigorngul, P.; Sangvanich, P.; Rengpipat, S.; Hoven, V.P. Detection of the shrimp pathogenic bacteria, Vibrio harveyi, by a quartz crystal microbalance-specific antibody based sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 145, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.R.; Kim, G.; Kothapalli, A.; Morgan, M.T.; Ess, D. Detection of Salmonella enteritidis using a miniature optical surface plasmon resonance biosensor. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2007, 61, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, C.A.; Alocilja, E.C.; Osburn, W.N. Detection of E. coli O157:H7 using a miniaturized surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2005, 48, 2409–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraldo, D.; Mutharasan, R. Detection and confirmation of Staphylococcal enterotoxin B in apple juice and milk using piezoelectric-excited millimeter-sized cantilever sensors at 2.5 fg/mL. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 7636–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, F.; Uludag, Y.; Tothill, I.E. Real-time and sensitive detection of Salmonella Typhimurium using an automated quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) instrument with nanoparticles amplification. Talanta 2013, 115, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.L.; Li, Y. A QCM immunosensor for Salmonella detection with simultaneous measurements of resonant frequency and motional resistance. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2005, 21, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puttharugsa, C.; Wangkam, T.; Huangkamhang, N.; Gajanandana, O.; Himananto, O.; Sutapun, B.; Amarit, R.; Somboonkaew, A.; Srikhirin, T. Development of surface plasmon resonance imaging for detection of Acidovorax avenae subsp. citrulli (Aac) using specific monoclonal antibody. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 2341–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlermroj, R.; Oplatowska, M.; Gajanandana, O.; Himananto, O.; Grant, I.R.; Karoonuthaisiri, N.; Elliott, C.T. Strategies to improve the surface plasmon resonance-based immmunodetection of bacterial cells. Microchim. Acta 2013, 180, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, N.B.; Salgado, A.M.; Valdman, B. The evolution and developments of immunosensors for health and environmental monitoring: Problems and perspectives. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2009, 26, 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waswa, J.W.; Debroy, C.; Irudayaraj, J. Rapid detection of Salmonella enteritidis and Escherichia coli using surface plasmon resonance biosensor. J. Food Process Eng. 2006, 29, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Mutharasan, R. Rapid and sensitive immunodetection of Listeria monocytogenes in milk using a novel piezoelectric cantilever sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 45, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Arutyunov, D.; McDermott, M.T.; Szymanski, C.M.; Evoy, S. Specific detection of Campylobacter jejuni using the bacteriophage NCTC 12673 receptor binding protein as a probe. Analyst 2011, 136, 4780–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, M.; Sim, J.; Kang, T.; Nguyen, H.H.; Park, H.K.; Chung, B.H.; Ryu, S. A novel and highly specific phage endolysin cell wall binding domain for detection of Bacillus cereus. Eur. Biophys. J. 2015, 44, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karoonuthaisiri, N.; Charlermroj, R.; Morton, M.J.; Oplatowska-Stachowiak, M.; Grant, I.R.; Elliott, C.T. Development of a M13 bacteriophage-based SPR detection using Salmonella as a case study. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 190, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farka, Z.; Kovár, D.; Pribyl, J.; Skládal, P. Piezoelectric and surface plasmon resonance biosensors for Bacillus atrophaeus spores. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Si, C.; Ying, Y. Subtractive inhibition assay for the detection of E. coli O157:H7 using surface plasmon resonance. Sensors 2011, 11, 2728–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skottrup, P.D.; Leonard, P.; Kaczmarek, J.Z.; Veillard, F.; Enghild, J.J.; O’Kennedy, R.; Sroka, A.; Clausen, R.P.; Potempa, J.; Riise, E. Diagnostic evaluation of a nanobody with picomolar affinity toward the protease RgpB from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Anal. Biochem. 2011, 415, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.-B.; Bi, L.-J.; Zhang, Z.-P.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Yang, R.-F.; Wei, H.-P.; Zhou, Y.-F.; Zhang, X.-E. Label-free detection of B. anthracis spores using a surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Analyst 2009, 134, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Irudayaraj, J.; Ryan, T. Mono and dithiol surfaces on surface plasmon resonance biosensors for detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2006, 114, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Vinuesa, J.L.; Hidalgo-Álvarez, R.; De, L.N.F.J.; Davey, C.L.; Newman, D.J.; Price, C.P. Characterization of immunoglobulin G bound to latex particles using surface plasmon resonance and electrophoretic mobility. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 204, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gnedenko, O.V.; Mezentsev, Y.V.; Molnar, A.A.; Lisitsa, A.V.; Ivanov, A.S.; Archakov, A.I. Highly sensitive detection of human cardiac myoglobin using a reverse sandwich immunoassay with a gold nanoparticle-enhanced surface plasmon resonance biosensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 759, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Phipps-Todd, B. Improvement of capture efficacy of immunomagnetic beads for Campylobacter jejuni using reagents that alter its motility. Can. J. Microbiol. 2013, 59, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, R.-P.; Yao, G.-H.; Fan, L.-X.; Qiu, J.-D. Magnetic Fe3O4@Au composite-enhanced surface plasmon resonance for ultrasensitive detection of magnetic nanoparticle-enriched α-fetoprotein. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 737, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavi, M.Z.; Chen, H.-Y.; Wu, S.-H.; Peng, S.-W.; Lee, K.-L.; Wei, P.-K.; Cheng, J.-Y. Magnetic nanoparticle-enhanced SPR on gold nanoslits for ultra-sensitive, label-free detection of nucleic acid biomarkers. Analyst 2013, 138, 2740–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Song, D. A novel surface plasmon resonance biosensor based on graphene oxide decorated with gold nanorod-antibody conjugates for determination of transferrin. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 45, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenzl, C.; Hirsch, T.; Baeumner, A.J. Liposomes with high refractive index encapsulants as tunable signal amplification tools in surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 11157–11163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makszin, L.; Péterfi, Z.; Blaskó, A.; Sándor, V.; Kilár, A.; Dörnyei, A.; Osz, E.; Kilár, F.; Kocsis, B. Structural background for serological cross-reactivity between bacteria of different enterobacterial serotypes. Electrophoresis 2015, 36, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochel, I.; Slavíčková, D.; Viochna, D.; Škvor, J.; Steinhauserová, I. Detection of Campylobacter species in foods by indirect competitive ELISA using hen and rabbit antibodies. Food Agric. Immunol. 2007, 18, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).