A Zinc Oxide Nanorod-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor for the Detection of Tumor Markers in Saliva

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

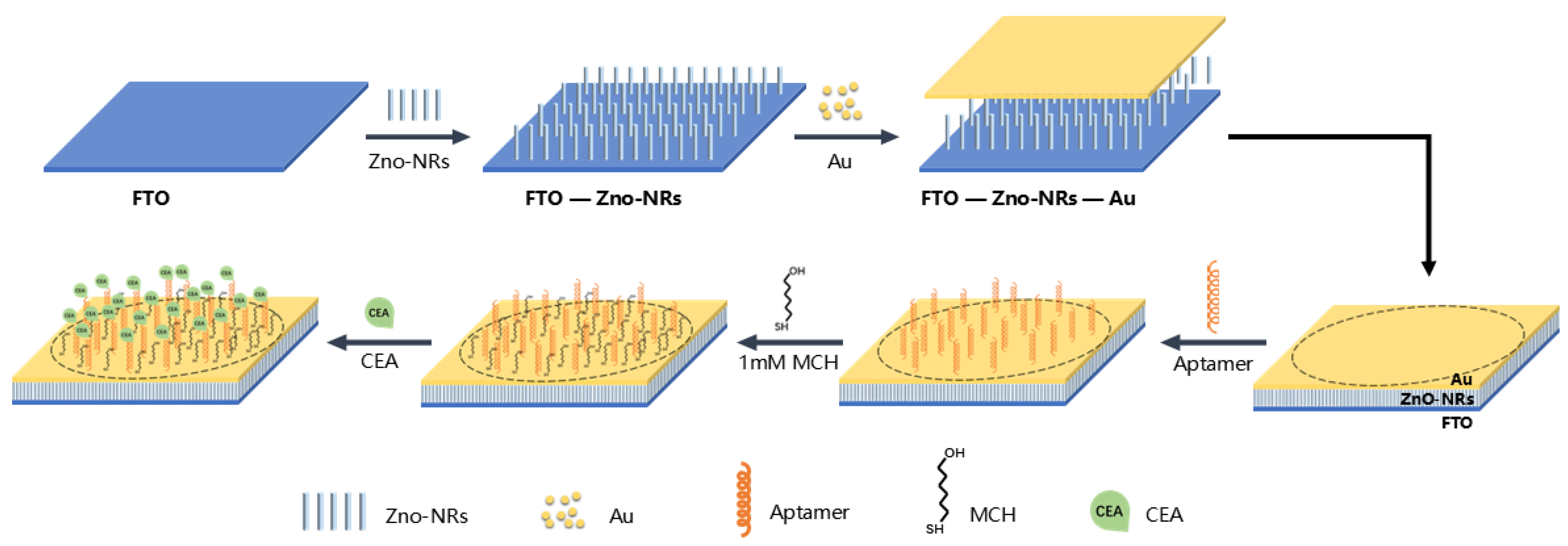

2.2. Preparation of FTO-ZnO-Au Structure

2.3. Immobilization of Aptamer

2.4. Electrical Measurement

2.5. Saliva Sample Collection

2.6. Signal Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

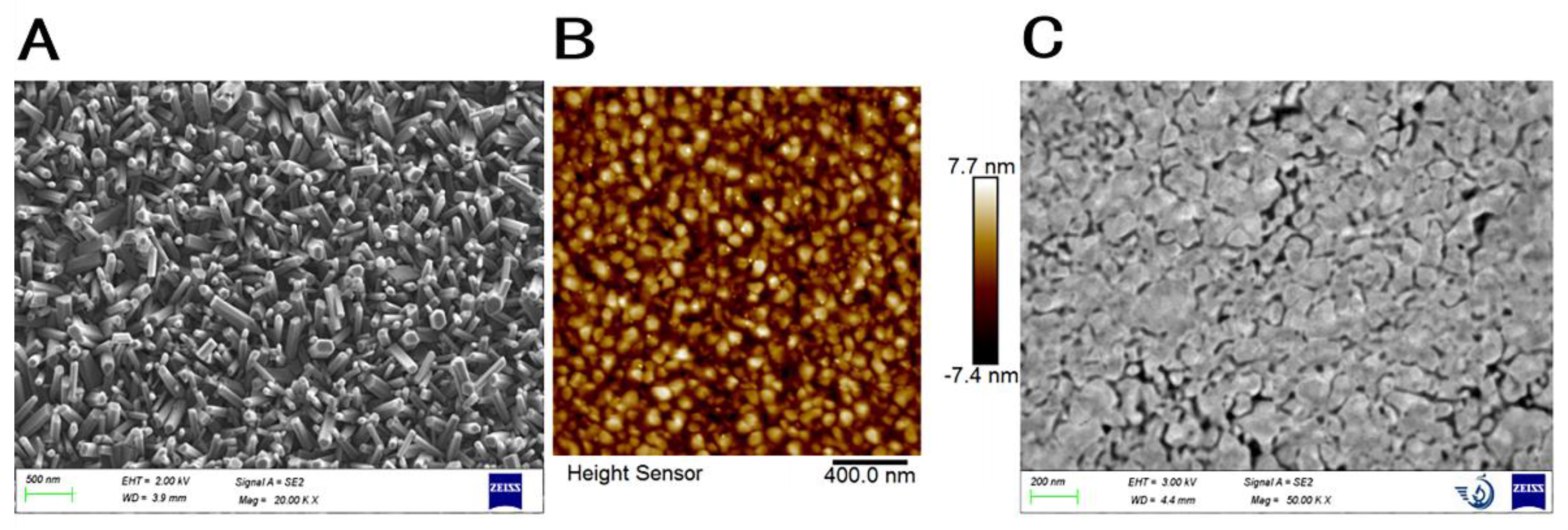

3.1. Characterization of Prepared FTO-ZnO-Au Structure

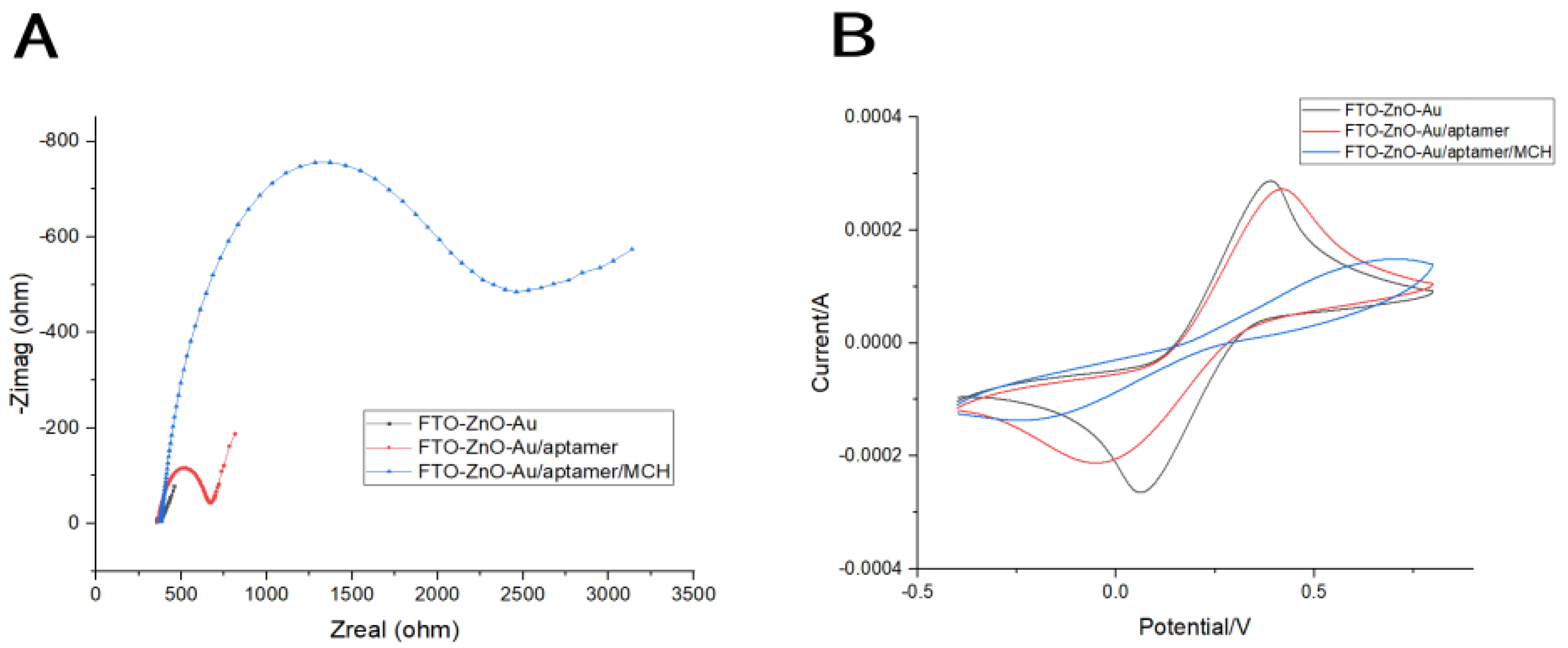

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization of Aptasensor Preparation

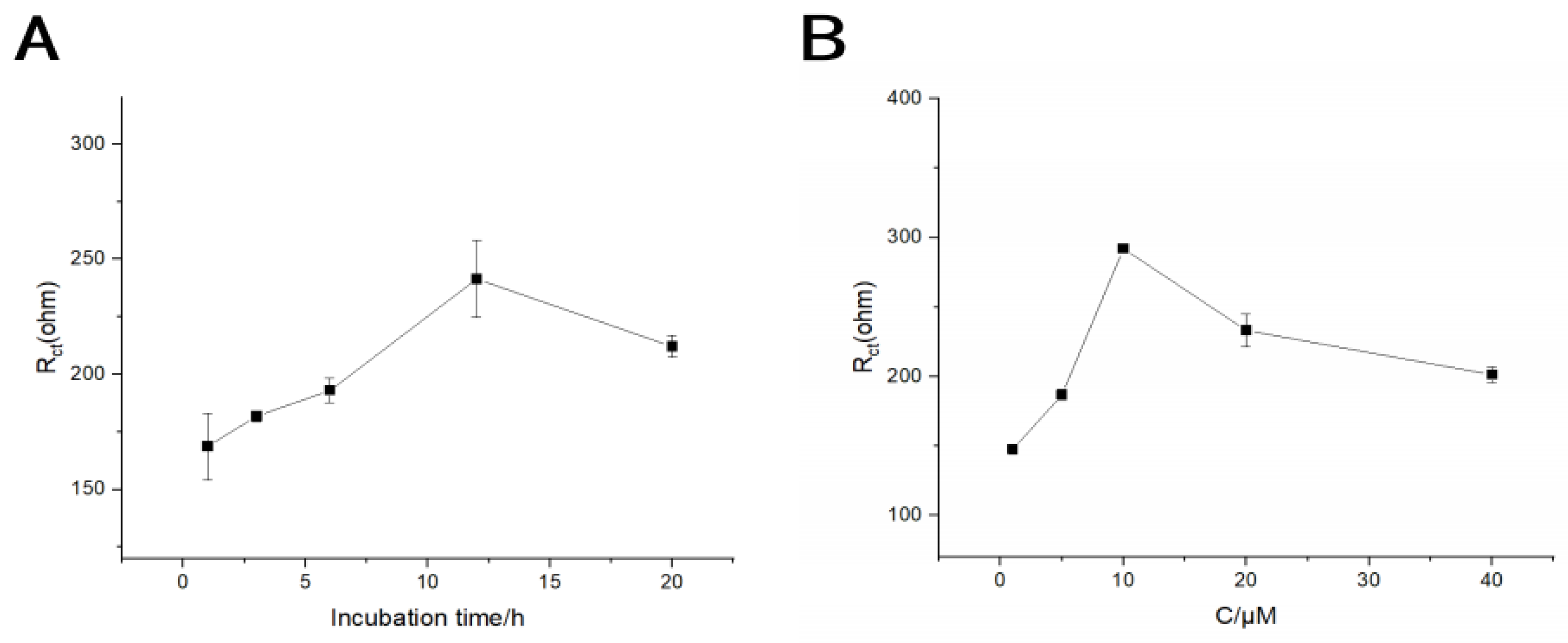

3.3. Optimization of Measurement Conditions

3.4. Analytical Performance Testing of Electrochemical Aptasensor

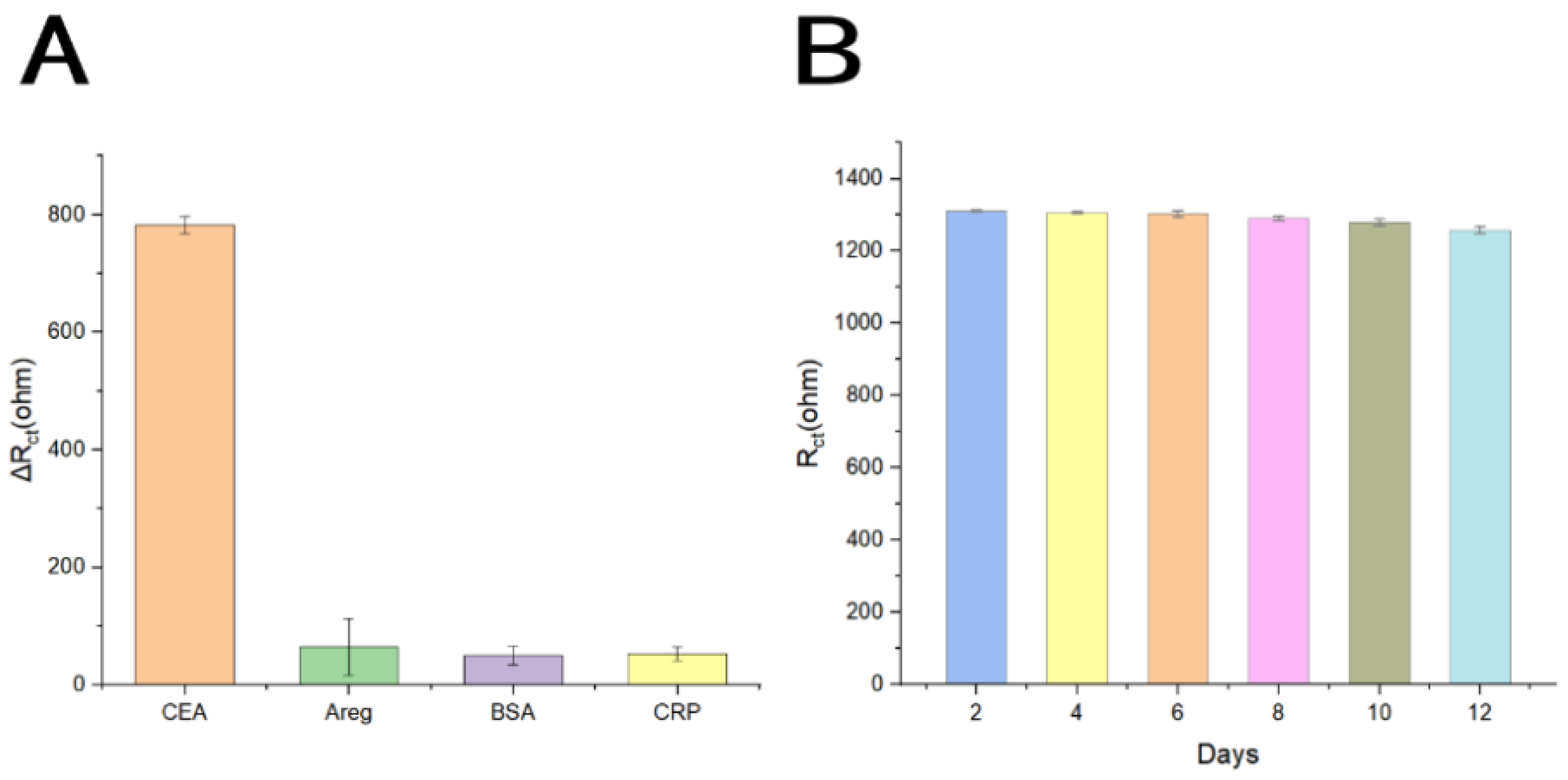

3.5. Selectivity, Reproducibility, Stability, and Regeneration of the Aptasensor

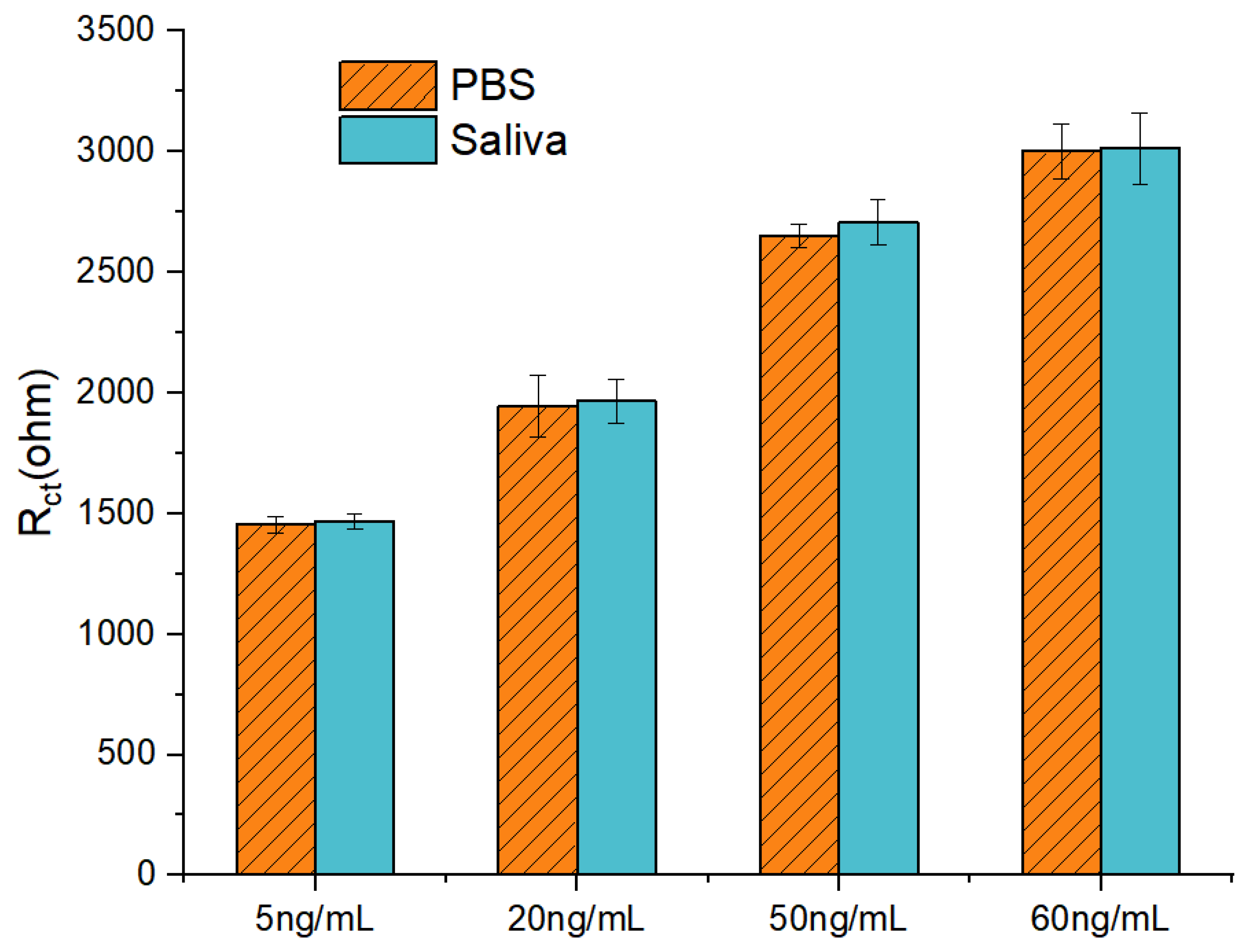

3.6. Anti-Interference Performance and Preliminary Analysis of Human Saliva Samples

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badwelan, M.; Muaddi, H.; Ahmed, A.; Lee, K.T.; Tran, S.D. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Concomitant Primary Tumors, What Do We Know? A Review of the Literature. Curr. Oncol. 2023, 30, 3721–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugshan, A.; Farooq, I. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Metastasis, potentially associated malignant disorders, etiology and recent advancements in diagnosis. F1000Research 2020, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, S.; Han, Q.; Cheng, L. Role of Oral Bacteria in the Development of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Feghali, K.A.; Ghanem, A.I.; Burmeister, C.; Chang, S.S.; Ghanem, T.; Keller, C.; Siddiqui, F. Impact of smoking on pathological features in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2019, 15, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbesi Bellantoni, M.; Picciolo, G.; Pirrotta, I.; Irrera, N.; Vaccaro, M.; Vaccaro, F.; Squadrito, F.; Pallio, G. Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma: An Update of the Pharmacological Treatment. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Natarajan, C.; Mukherjee, A. Advances in oral cancer detection. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2019, 91, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S.; Khan, R.S.; Najeeb, S.; Slowey, P.D.; Rehman, I.U. Role of Salivary Biomarkers in Oral Cancer Detection. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2018, 86, 23–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abati, S.; Bramati, C.; Bondi, S.; Lissoni, A.; Trimarchi, M. Oral Cancer and Precancer: A Narrative Review on the Relevance of Early Diagnosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldoni, R.; Scolaro, A.; Boccalari, E.; Dolci, C.; Scarano, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Ravazzani, P.; Muti, P.; Tartaglia, G. Malignancies and Biosensors: A Focus on Oral Cancer Detection through Salivary Biomarkers. Biosensors 2021, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayanthi, V.; Das, A.B.; Saxena, U. Recent advances in biosensor development for the detection of cancer biomarkers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Yang, H.C.; Rhee, W.J. Simultaneous multiplexed detection of exosomal microRNAs and surface proteins for prostate cancer diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 146, 111749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.L.; Zhang, Z.L.; Tang, M.; Zhu, D.L.; Dong, X.J.; Hu, J.; Qi, C.B.; Tang, H.W.; Pang, D.W. Spectrally Combined Encoding for Profiling Heterogeneous Circulating Tumor Cells Using a Multifunctional Nanosphere-Mediated Microfluidic Platform. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 11240–11244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Sun, L.; Yuan, W.; Xu, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, F.; Sun, L.; Zeng, Y. Clinical value of Naa10p and CEA levels in saliva and serum for diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajguru, J.P.; Mouneshkumar, C.D.; Radhakrishnan, I.C.; Negi, B.S.; Maya, D.; Hajibabaei, S.; Rana, V. Tumor markers in oral cancer: A review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrin, P.S.; Jamal, F.I.; Roeckendorf, N.; Wenger, C. Development of a Portable Dielectric Biosensor for Rapid Detection of Viscosity Variations and Its In Vitro Evaluations Using Saliva Samples of COPD Patients and Healthy Control. Healthcare 2019, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senf, B.; Yeo, W.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Recent Advances in Portable Biosensors for Biomarker Detection in Body Fluids. Biosensors 2020, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, S.; Chen, C.; Alifu, N.; Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Li, C.; Xu, L.; Wang, L.; Dong, B. Opal photonic crystal-enhanced upconversion turn-off fluorescent immunoassay for salivary CEA with oral cancer. Talanta 2023, 258, 124435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Wang, K.; Xiao, K.; Hou, Y.; Lu, W.; Xu, H.; Wo, Y.; Feng, S.; Cui, D. Carcinoembryonic antigen detection with “Handing”-controlled fluorescence spectroscopy using a color matrix for point-of-care applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 90, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, J.; Kakooei, S.; Sadeghzadeh, S.M.; Rouhi, O.; Karimzadeh, R. Highly efficient photocatalytic performance of dye-sensitized K-doped ZnO nanotapers synthesized by a facile one-step electrochemical method for quantitative hydrogen generation. J. Solid. State Electrochem. 2020, 24, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Cao, B.; Qin, Q.; Liao, X.; Wo, Y.; Jin, Q.; Cui, D. Smartphone-imaged multilayered paper-based analytical device for colorimetric analysis of carcinoembryonic antigen. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 2517–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiong, Q.; Xiao, F.; Duan, H. 2D nanomaterials based electrochemical biosensors for cancer diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 89, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Jia, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Dong, Y. Sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor for sensitive detection of CEA based on the enhanced effects of Ag NPs@CS spaced Hemin/rGO. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 126, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paniagua, G.; Villalonga, A.; Eguílaz, M.; Vegas, B.; Parrado, C.; Rivas, G.; Díez, P.; Villalonga, R. Amperometric aptasensor for carcinoembryonic antigen based on the use of bifunctionalized Janus nanoparticles as biorecognition-signaling element. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1061, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsuddin, S.H.; Gibson, T.D.; Tomlinson, D.C.; McPherson, M.J.; Jayne, D.G.; Millner, P.A. Reagentless Affimer- and antibody-based impedimetric biosensors for CEA-detection using a novel non-conducting polymer. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 178, 113013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, K.; Li, S.; He, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, N.; Du, M. Impedimetric aptasensor based on zirconium-cobalt metal-organic framework for detection of carcinoembryonic antigen. Mikrochim. Acta 2022, 189, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashkavayi, A.B.; Raoof, J.B.; Ojani, R. Preparation of Epirubicin Aptasensor Using Curcumin as Hybridization Indicator: Competitive Binding Assay between Complementary Strand of Aptamer and Epirubicin. Electroanalysis 2017, 30, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J. Recent Progress and Opportunities for Nucleic Acid Aptamers. Life 2021, 11, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Ming, T.; Tang, S.; Ren, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, M.; Tao, Q.; Xu, H. Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer: Pathogenic role and therapeutic target. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, F.; Chen, X.; Fang, H.; Zha, C.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Mohamed Ahmed, M.B.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Dual-ratiometric aptasensor for simultaneous detection of malathion and profenofos based on hairpin tetrahedral DNA nanostructures. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 227, 114853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maral, M.; Erdem, A. Carbon Nanofiber-Ionic Liquid Nanocomposite Modified Aptasensors Developed for Electrochemical Investigation of Interaction of Aptamer/Aptamer–Antisense Pair with Activated Protein C. Biosensors 2023, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-W.; Du, L.; Liu, M.-X.; Wang, J.-H.; Chen, S.; Yu, Y.-L. All-in-one nanoflare biosensor combined with catalyzed hairpin assembly amplification for in situ and sensitive exosomal miRNA detection and cancer classification. Talanta 2024, 266, 125145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, L.; Tang, D. ZIF-8-Assisted NaYF4:Yb,Tm@ZnO Converter with Exonuclease III-Powered DNA Walker for Near-Infrared Light Responsive Biosensor. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 1470–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Que, M.; Lin, C.; Sun, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Sun, Y. Progress in ZnO Nanosensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetti, N.P.; Bukkitgar, S.D.; Reddy, K.R.; Reddy, C.V.; Aminabhavi, T.M. ZnO-based nanostructured electrodes for electrochemical sensors and biosensors in biomedical applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 141, 111417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Yu, X.; He, H.; Cao, G.; Lu, H.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, S.Y. Smartphone-Based Point-of-Care Microfluidic Platform Fabricated with a ZnO Nanorod Template for Colorimetric Virus Detection. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 3298–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, K.; Chakraborty, B.; Chaudhury, S.S.; Chaudhuri, C.R.; Chattopadhyay, S.K.; Das Mukhopadhyay, C. Selective, Ultra-Sensitive, and Rapid Detection of Serotonin by Optimized ZnO Nanorod FET Biosensor. IEEE Trans. NanoBiosci. 2022, 21, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. From nanogenerators to piezotronics—A decade-long study of ZnO nanostructures. MRS Bull. 2012, 37, 814–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Nagal, V.; Masrat, S.; Tuba, T.; Alam, S.; Bhat, K.S.; Wahid, I.; Ahmad, R. Vertically Oriented Zinc Oxide Nanorod-Based Electrolyte-Gated Field-Effect Transistor for High-Performance Glucose Sensing. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 8867–8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Zhou, W.; Tavakoli, H.; Bautista, C.; Xia, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Aptamer-functionalized metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for biosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 176, 112947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dai, L.; Yao, J.; Guo, T.; Hrynsphan, D.; Tatsiana, S.; Chen, J. Enhanced adsorption and reduction performance of nitrate by Fe–Pd–Fe3O4 embedded multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, A.-J.; Yuan, P.-X.; Luo, X.; Xue, Y.; Feng, J.-J. Three dimensional sea-urchin-like PdAuCu nanocrystals/ferrocene-grafted-polylysine as an efficient probe to amplify the electrochemical signals for ultrasensitive immunoassay of carcinoembryonic antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 132, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouyandeh, M.; Sajadi, S.M.; Seidi, F.; Habibzadeh, S.; Munir, M.T.; Abida, O.; Ahmadi, S.; Kowalkowska-Zedler, D.; Rabiee, N.; Rabiee, M.; et al. Metal nanoparticles-assisted early diagnosis of diseases. OpenNano 2022, 8, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-M.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, S.-K. Fiber optic sensor based on ZnO nanowires decorated by Au nanoparticles for improved plasmonic biosensor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Wen, W.; Lin, F.G.; Zhang, X.H.; Gu, H.S.; Wang, S.F. Simplified aptamer-based colorimetric method using unmodified gold nanoparticles for the detection of carcinoma embryonic antigen. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 10994–10999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Kallappa, S.; Kumar, P.; Shukla, S.; Ghosh, R. Simple diagnosis of cancer by detecting CEA and CYFRA 21-1 in saliva using electronic sensors. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honarmand, M.H.; Farhad-Mollashahi, L.; Nakhaee, A.; Nehi, M. Salivary Levels of ErbB2 and CEA in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, C.; Ma, R.; Sha, Z.; Liang, F.; Sun, S. Aptamer-based biosensing through the mapping of encoding upconversion nanoparticles for sensitive CEA detection. Analyst 2022, 147, 3350–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi, N.; Hosseinkhani, S.; Ranjbar, B. A facile and rapid aptasensor based on split peroxidase DNAzyme for visual detection of carcinoembryonic antigen in saliva. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 253, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, X.; Duan, Y. Capillary-Based Three-Dimensional Immunosensor Assembly for High-Performance Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen Using Laser-Induced Fluorescence Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analytical Method | Sensitive Elements | Analytes | Linear Ranges (ng/mL) | LOD (ng/mL) | R2 | Reference | Real Sample Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroimmunosensor | Anti-CEA antibody | CEA | 1 × 10−1~2.5 2.5~20 | 1.0 × 10−1 | 0.988 0.996 | [17] | Yes |

| Aptasensor | Aptamer | CEA | 2 × 10−2~6.0 | 3.25 × 10−1 | 0.962 | [47] | No |

| Aptasensor | Aptamer | CEA | 1~50 | 1.0 | 0.990 | [48] | Yes |

| Fluoroimmunosensor | Anti-CEA antibody | CEA | 7 × 10−1~80 | 5.5 × 10−3 | 0.993 | [49] | Yes |

| Aptasensor | Aptamer | CEA | 1~80 | 7.5 × 10−1 | 0.999 | This work | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Ding, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lin, J.; Cao, R.; Wang, M.; Tan, Y.; Zong, X.; Qu, Z.; et al. A Zinc Oxide Nanorod-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor for the Detection of Tumor Markers in Saliva. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors12100203

Li J, Ding Y, Shi Y, Liu Z, Lin J, Cao R, Wang M, Tan Y, Zong X, Qu Z, et al. A Zinc Oxide Nanorod-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor for the Detection of Tumor Markers in Saliva. Chemosensors. 2024; 12(10):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors12100203

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Junrong, Yihao Ding, Yuxuan Shi, Zhiying Liu, Jun Lin, Rui Cao, Miaomiao Wang, Yushuo Tan, Xiaolin Zong, Zhan Qu, and et al. 2024. "A Zinc Oxide Nanorod-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor for the Detection of Tumor Markers in Saliva" Chemosensors 12, no. 10: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors12100203

APA StyleLi, J., Ding, Y., Shi, Y., Liu, Z., Lin, J., Cao, R., Wang, M., Tan, Y., Zong, X., Qu, Z., Du, L., & Wu, C. (2024). A Zinc Oxide Nanorod-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor for the Detection of Tumor Markers in Saliva. Chemosensors, 12(10), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors12100203