Implementation of the Multidisciplinary Guideline on Chronic Pain in Vulnerable Nursing Home Residents to Improve Recognition and Treatment: A Qualitative Process Evaluation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

2.2. Sample

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Materials

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Opinions of Professionals before Implementation (T0)

- Need for implementation:

- Recognizing pain:

- Measurement instruments:

- Non-pharmacological treatments:

- Pharmacological treatments:

- Healthcare organization:

- Education:

- Project management:

3.2. Phase 1: Preparation (6 Months)

3.2.1. Preparations by the Pain Team

3.2.2. Working Procedures for the Pain Team

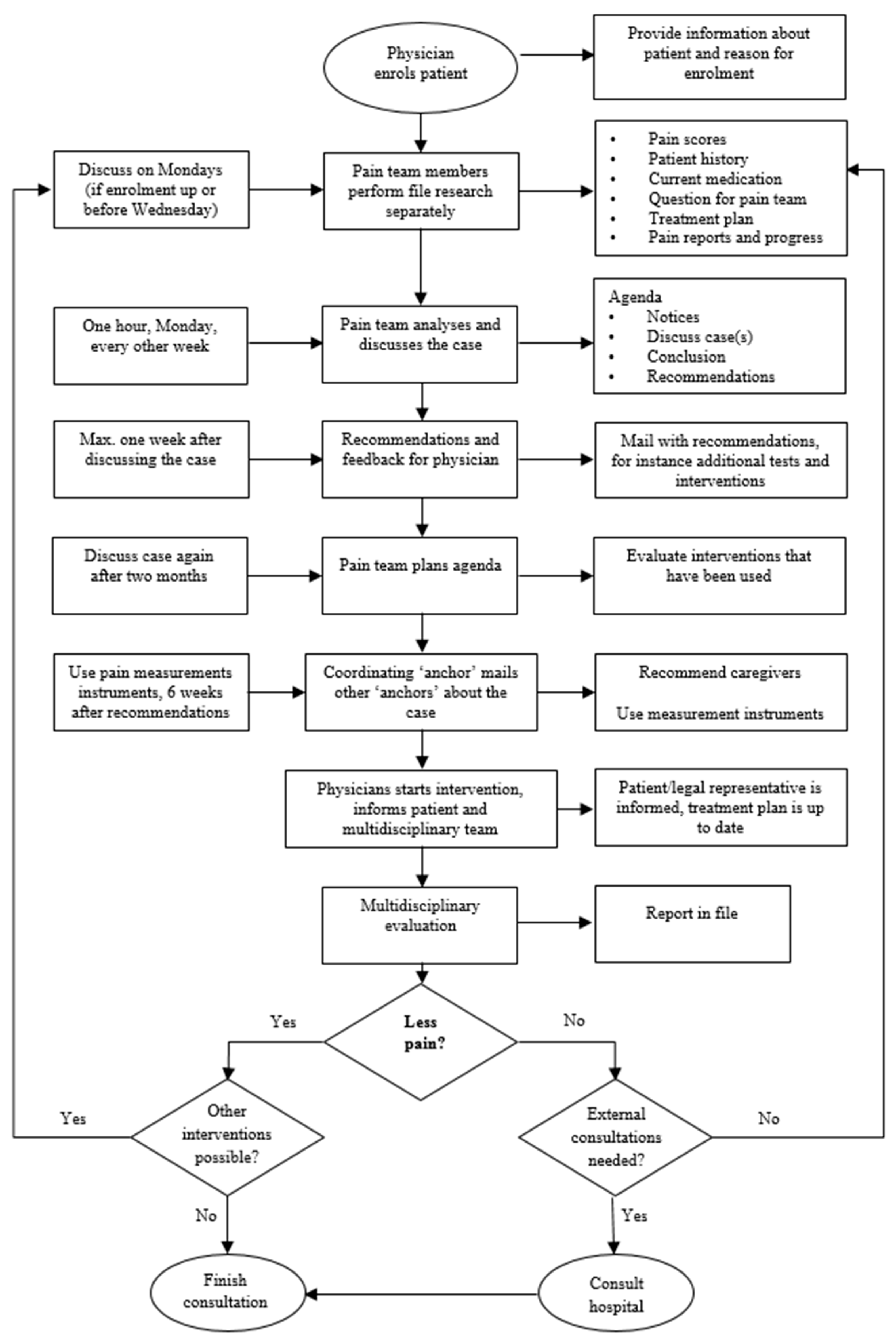

3.3. Phase 2: Implementation of the Guideline (8 Months)

- Pain diagnostics:

- Measurement instruments:

- Non-pharmacological treatments:

- Pharmacological treatments:

- Healthcare organization pain team:

- Education:

- Advice for future implementation in other nursing homes:

- Sustaining implementation over the longer term:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulla, A.; Adams, N.; Bone, M.; Elliott, A.M.; Gaffin, J.; Jones, D.; Knaggs, R.; Martin, D.; Sampson, L.; Schofield, P. Guidance on the management of pain in older people. Age Ageing 2013, 42 (Suppl. 1), i1–i57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barber, J.B.; Gibson, S.J. Treatment of chronic non-malignant pain in the elderly: Safety considerations. Drug Saf. 2009, 32, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achterberg, W.; Lautenbacher, S.; Husebo, B.; Erdal, A.; Herr, K. Pain in dementia. Pain Rep. 2020, 5, e803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riswold, K.; Brech, A.; Peterson, R.; Schepper, S.; Wegehaupt, A.; Larsen-Engelkes, T.J.; Alexander, J.W.; Barnett, R.T.; Kappel, S.E.; Joffer, B.; et al. A Biopsychosocial Approach to Pain Management. South Dak. Med. J. South Dak. State Med Assoc. 2018, 71, 501–504. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.R.; Ehrhardt, K.P.; Ripoll, J.G.; Sharma, B.; Padnos, I.W.; Kaye, R.J.; Kaye, A.D. Pain in the Elderly. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2016, 20, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjistavropoulos, T.; Herr, K.; Turk, D.C.; Fine, P.G.; Dworkin, R.H.; Helme, R.; Jackson, K.; Parmelee, P.A.; Rudy, T.E.; Lynn Beattie, B.; et al. An interdisciplinary expert consensus statement on assessment of pain in older persons. Clin. J. Pain 2007, 23, S1–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achterberg, W.P. How can the quality of life of older patients living with chronic pain be improved? Pain Manag. 2019, 9, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Verenso. Multidisciplinaire Richtlijn Pijn, Herkenning en Behandeling van Pijn Bij Kwetsbare Ouderen [Multidisciplinary Guideline Recognition and Treatment of Pain in Vulnerable Elderly]; Verenso: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; update 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg, W.P.; de Ruiter, C.M.; de Weerd-Spaetgens, C.M.; Geels, P.; Horikx, A.; Verduijn, M.M. Multidisciplinary guideline ‘Recognition and treatment of chronic pain in vulnerable elderly people. Ned. Tijdschr. Voor Geneeskd. 2012, 155, A4606. [Google Scholar]

- Brunkert, T.; Ruppen, W.; Simon, M.; Zuniga, F. A theory-based hybrid II implementation intervention to improve pain management in Swiss nursing homes: A mixed-methods study protocol. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunkert, T.; Simon, M.; Ruppen, W.; Zuniga, F. Pain Management in Nursing Home Residents: Findings from a Pilot Effectiveness-Implementation Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 2574–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonski, A.; Ersek, M. Nursing home staff adherence to evidence-based pain management practices. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 35, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ersek, M.; Neradilek, M.B.; Herr, K.; Jablonski, A.; Polissar, N.; Du Pen, A. Pain Management Algorithms for Implementing Best Practices in Nursing Homes: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doherty, S. Evidence-based implementation of evidence-based guidelines. Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2006, 19, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinuff, T.; Kahnamoui, K.; Cook, D.J.; Giacomini, M. Practice guidelines as multipurpose tools: A qualitative study of noninvasive ventilation. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wensing, M.; Grol, R. Implementation. Effective Improvement of Patient Care, 7th revised ed.; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Houten, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg, W.C.M.; Husebo, B.S. Towards academic nursing home medicine: A Dutch example for Norway? Omsorg 2015, 1, 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, R.T.; Lavrijsen, J.C.; Hoek, J.F.; Went, P.B.; Schols, J.M. Dutch elderly care physician: A new generation of nursing home physician specialists. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 1807–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schols, J.M. Nursing home medicine in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Gen. Pr. 2005, 11, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moser, A.; Korstjens, I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. Eur. J. Gen. Pr. 2018, 24, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bengtsson, M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. Nurs. Open 2016, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ZonMw. [Maak zelf een Implementatieplan.]. Available online: https://publicaties.zonmw.nl/maak-zelf-een-implementatieplan/ (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- Van Het Groenewoud, H. Brochure Pain Suffering, Not Necessary. Tips for Patients, Family and Caregivers, 2nd ed.; IVM, Dutch Institute for Rational use of Medicine: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zwakhalen, S.M.; Hamers, J.P.; Berger, M.P. The psychometric quality and clinical usefulness of three pain assessment tools for elderly people with dementia. Pain 2006, 126, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchionni, C.; Ritchie, J. Organizational factors that support the implementation of a nursing best practice guideline. J. Nurs Manag 2008, 16, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, M.J.C.; Achterberg, W.P.; van der Steen, J.T.; Francke, A.L. Implementation of a Stepwise, Multidisciplinary Intervention for Pain and Challenging Behaviour in Dementia (STA OP!): A Process Evaluation. Int. J. Integr Care 2018, 18, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, R.; Martin, G.; Banerjee, J.; Butler, L.; Pattison, T.; Cruickshank, L.; Maries-Tillott, C.; Wilson, T.; Damery, S.; Meyer, J.; et al. Improving the Quality of Care in Care Homes Using the Quality Improvement Collaborative Approach: Lessons Learnt from Six Projects Conducted in the UK and The Netherlands. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunkert, T.; Simon, M.; Zuniga, F. Use of Pain Management Champions to Enhance Guideline Implementation by Care Workers in Nursing Homes. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2021, 18, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veal, F.; Williams, M.; Bereznicki, L.; Cummings, E.; Thompson, A.; Peterson, G.; Winzenberg, T. Barriers to Optimal Pain Management in Aged Care Facilities: An Australian Qualitative Study. Pain Manag. Nurs. Off. J. Am. Soc. Pain Manag. Nurses 2018, 19, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, K.S.; Duran, C.; Fink, R. Evidence-based policy and procedures: An algorithm for success. J. Nurs. Adm. 2008, 38, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwakhalen, S.M.; van’t Hof, C.E.; Hamers, J.P. Systematic pain assessment using an observational scale in nursing home residents with dementia: Exploring feasibility and applied interventions. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 3009–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, A.; Balouchi, A.; Rezaie-Keikhaie, K.; Bouya, S.; Sheyback, M.; Rawajfah, O.A. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and clinical recommendation toward infection control and prevention standards among nurses: A systematic review. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2019, 47, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunkert, T.; Simon, M.; Ruppen, W.; Zuniga, F. A Contextual Analysis to Explore Barriers and Facilitators of Pain Management in Swiss Nursing Homes. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. Off. Publ. Sigma Tau Int. Honor Soc. Nurs. 2020, 52, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| T0 Baseline | T1 end of Implementation Phase | |

|---|---|---|

| Total participants, n | 21 | 18 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| 4 (19) | 2 (11) |

| 17 (81) | 16 (89) |

| Role or profession, n (%) | ||

| 1 (5) | 1 (6) |

| 3 (14) | 3 (6) |

| 1 (5) | 1 (6) |

| 13 (62) | 11 (61) |

| 3 (14) | 2 (11) |

| 1 | Structural use of pain measurement and observation tools | Behavior |

| 2 | A functioning pain team that has access to necessary means | Behavior |

| 3 | An educated pain team that is familiar with the multidisciplinary guideline ‘Recognition and treatment of chronic pain in vulnerable elderly’ by Verenso * [8] | Knowledge |

| 4 | Overview of prescriptions and review of pain medication available through the pharmacist | Behavior |

| 5 | Pharmacotherapy audit meetings supported by data provided by the pharmacist | Behavior |

| 6 | Nurses and physicians operate according to the guideline | Behavior |

| 7 | Nurses receive extra education through the e-learning module provided by IVM * | Knowledge |

| 8 | Pain is integrated as a care goal for all care professionals | Behavior |

| 9 | Paramedics receive extra pain education | Knowledge |

| 10 | Paramedics help other disciplines to find non-pharmacological treatments for pain | Attitude and behavior |

| 11 | Paramedics accurately and fully report pain in patient files and letters of transfer to ‘first-line’ care | Behavior |

| 12 | Residents and family have been informed with available information | Knowledge |

| 13 | Residents and family know who they can contact for more information on pain and (non-)pharmacological treatment options | Knowledge |

| 14 | Residents/legal representatives have been informed about the care and treatment plans | Knowledge |

| 15 | The client council is informed and updated about the progress of guideline implementation | Knowledge |

| Meeting 1 | Meeting 2 | Meeting 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | Goal | Action | 1st Evaluation | Action | 2nd Evaluation | Action |

| 1. Each NH resident will be systematically checked for pain complaints | After three months, 75% of vulnerable elderly have received a systematic check for pain complaints | Use of pain measurement instruments on pilot wards; role for ‘anchors’ | 75% is too high, goal is not reached; systematic check should be part of MDM and treatment plan | Handover to the attendings’ meetings; anchor personnel and physicians instruct other professionals to use instruments and document the outcomes | More systematic focus on pain is needed | Further promote and facilitate role of physicians and ‘anchor personnel’ |

| 2. Determine available and feasible non-pharmacological treatments for pain | At three months, there is a list of non-pharmacological treatments that physicians can use | The pain team and physicians create a list with available and feasible non-pharmacological treatments for pain | The pain team created a list, and non-pharmacological treatments are discussed during the attendings’ meetings. The pain policy is adjusted, with a description for each discipline | Agreement 2 will be maintained; request to share experiences with pain team; promote use of patient information flyer on pain | Only few cases are discussed with pain team | Promote use of flowchart to consult pain team; involve not only wards of pilot, but all wards of NH |

| 3. Chronic paracetamol users receive 2.5 g instead of 4.0 g/day | After three months, 95% of chronic users receive max 2.5 g/day. No paracetamol as needed (prn) on the psychogeriatric ward | Pharmacist makes list of all chronic users; to be evaluated by physicians, max 2.5 g. Physicians give all new paracetamol users 4.0 g/day for four weeks, after which an evaluation is planned. Check whether long-lasting opiates are prescribed instead. The pharmacist makes a list for paracetamol prn users. New dose is 2.5 g/day; 3 × 500 mg and 1 × 1000 mg at night | Some stress mentioned, differences in opinions between wards, and between patients. Overall, prescriptions conform with guideline. Large variation in prescriptions; work toward standard prescriptions, and define reason for prescription | Agreement 3 will be maintained but nuanced: evaluation moment after 2 to 4 weeks with note in file; when paracetamol and opiates are combined, note order of tapering off medication; consider laxatives with opiates | Only small improvements in cut down of doses of paracetamol to 2.5 or max 3.0 g/day. Cut down is difficult, e.g., when pain is chronic. Cut down of opiates is preferred. Laxatives are more consistently prescribed with opiates | Write the indication in the comments field; this helps to consciously decrease or stop pain medication |

| 4. Physicians no longer prescribe NSAIDs for vulnerable elderly without arthritis | After 1 month, vulnerable elderly without arthritis no longer receive NSAIDs | The pharmacist requires an explanation for NSAID prescriptions. The reasons are registered in the patient file and evaluations are planned | NSAIDs were not often prescribed. The agreement to stop prescription of NSAIDs is difficult for residents. Explaining side effects might prove beneficial | Agreement 4 will be maintained. Difficult to get freelancers † on board | No differences, despite notices from pharmacist. NSAID is needed, for e.g., for colic pain (prn). Physicians state: NH residents do not want to stop NSAIDs | Ending NSAID use is not feasible, write down indication and moment of evaluation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akker, L.E.v.d.; Waal, M.W.M.d.; Geels, P.J.E.M.; Poot, E.; Achterberg, W.P. Implementation of the Multidisciplinary Guideline on Chronic Pain in Vulnerable Nursing Home Residents to Improve Recognition and Treatment: A Qualitative Process Evaluation. Healthcare 2021, 9, 905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070905

Akker LEvd, Waal MWMd, Geels PJEM, Poot E, Achterberg WP. Implementation of the Multidisciplinary Guideline on Chronic Pain in Vulnerable Nursing Home Residents to Improve Recognition and Treatment: A Qualitative Process Evaluation. Healthcare. 2021; 9(7):905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070905

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkker, Lizanne E. van den, Margot W. M. de Waal, Paul J. E. M. Geels, Else Poot, and Wilco P. Achterberg. 2021. "Implementation of the Multidisciplinary Guideline on Chronic Pain in Vulnerable Nursing Home Residents to Improve Recognition and Treatment: A Qualitative Process Evaluation" Healthcare 9, no. 7: 905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070905

APA StyleAkker, L. E. v. d., Waal, M. W. M. d., Geels, P. J. E. M., Poot, E., & Achterberg, W. P. (2021). Implementation of the Multidisciplinary Guideline on Chronic Pain in Vulnerable Nursing Home Residents to Improve Recognition and Treatment: A Qualitative Process Evaluation. Healthcare, 9(7), 905. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070905