Causes and Severity of Dentophobia in Polish Adults—A Questionnaire Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Purpose of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Procedures

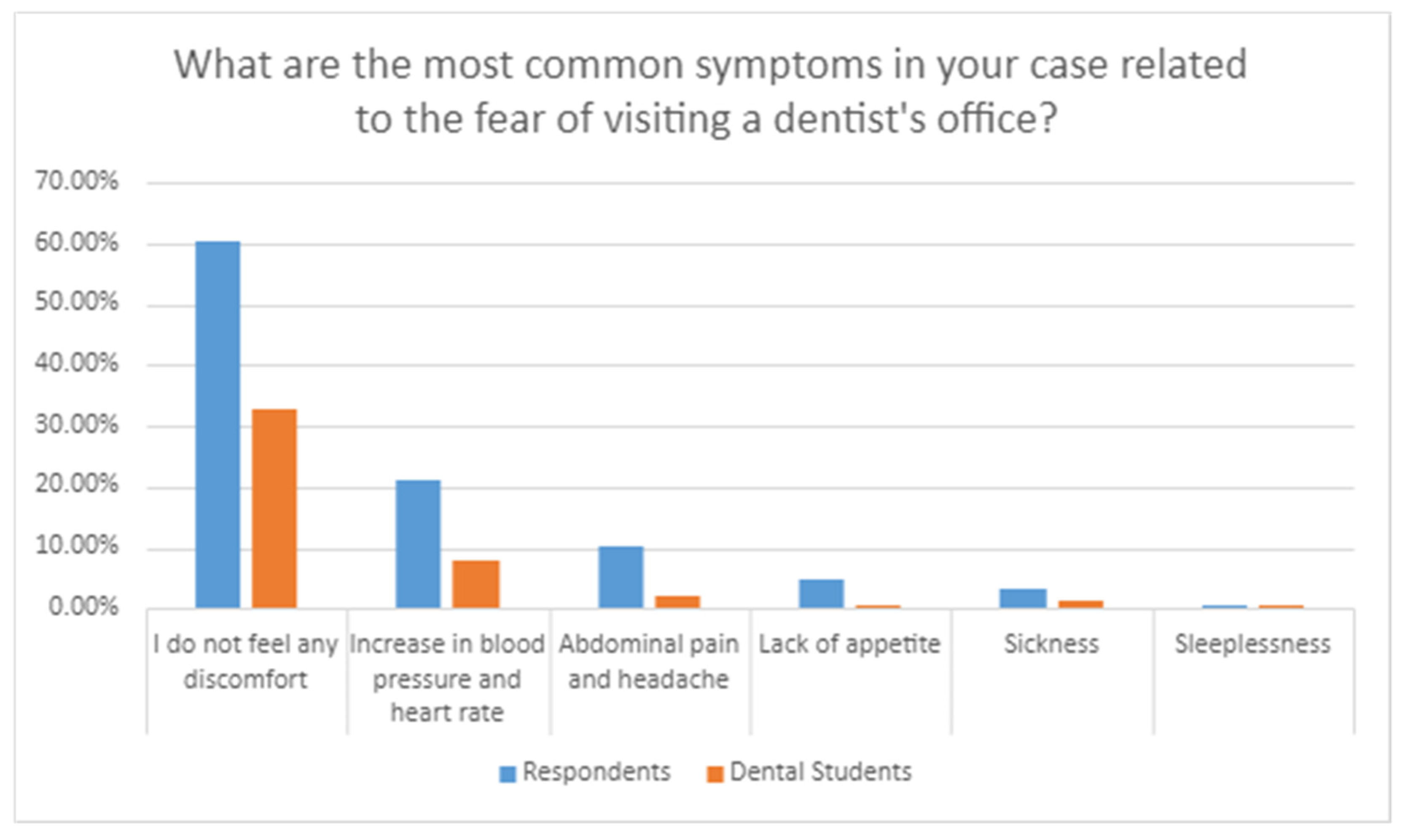

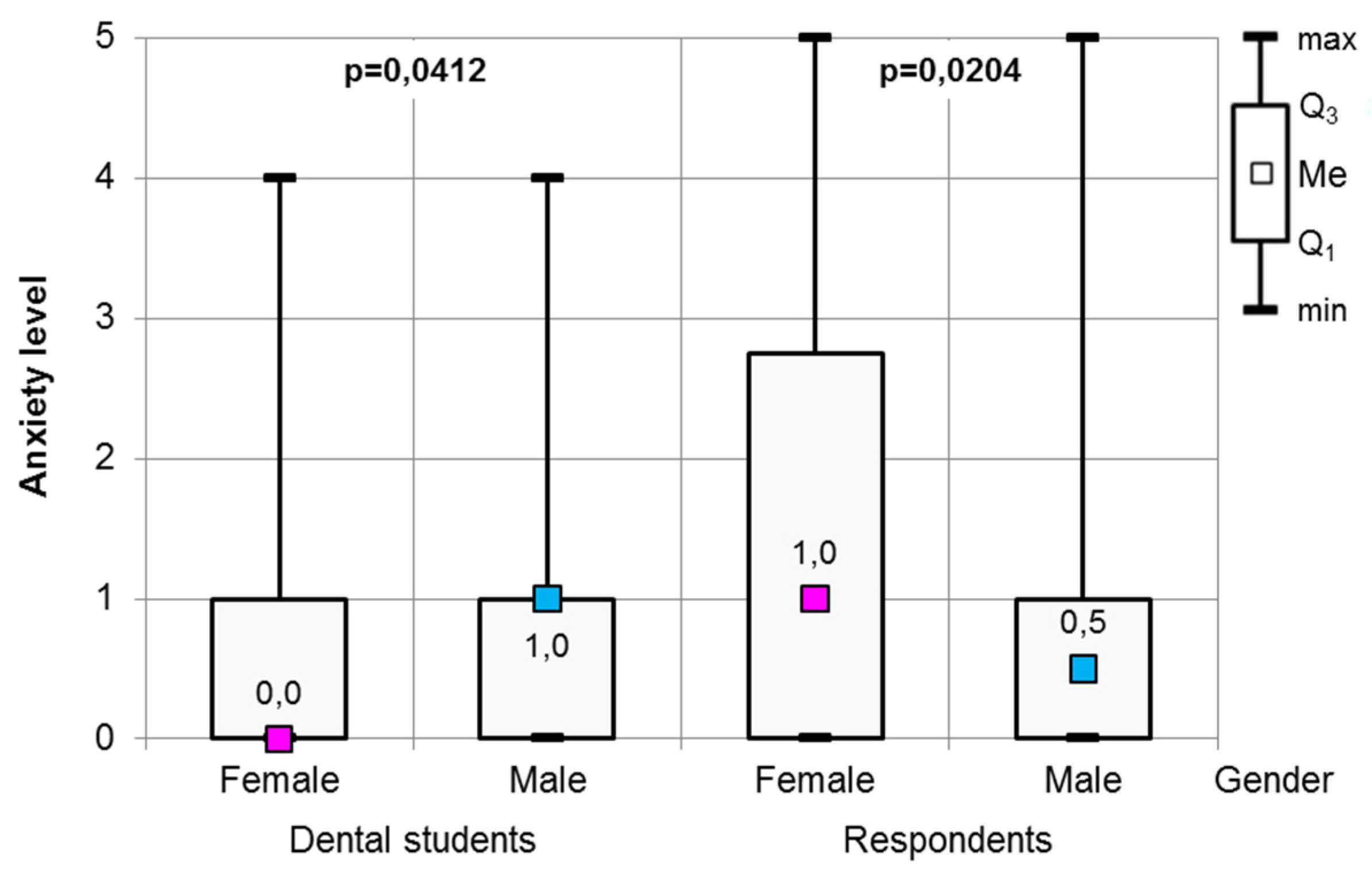

3. Results

3.1. Respondents

3.2. Dental Students

3.3. Dental Ankiety Scale

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAPD | The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry |

| CAMBRA | Caries Management by Risk Assessment |

| FPQ-III | Fear of Pain Questionnaire |

References

- Czerżyńska, M.; Orłow, P.; Milewska, A.J.; Choromańska, M. Dentophobia. Nowa. Stomatol. 2017, 22, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gruz, E.; Jaczewski, M.; Juzala, M. Analysis of anxiety level, factors modulating it and the stereotype of dentist in case of patients undergoing dental surgical treatment. Dent. Med. Probl. 2006, 43, 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, J.D.B.; Chaffee, B.W. The evidence for caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA®). Adv. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek, U.; Mysiak-Dębska, M.; Dębska, K.; Grzebieluch, W. Dental anxiety in students of the first years of the study of dentistry and medicine faculties. Dent. Med. Probl. 2010, 47, 343–349. [Google Scholar]

- Appukuttan, D.P. Strategies to manage patients with dental anxiety and dental phobia: Literature review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2016, 8, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopińska, K.; Olszewska, N.; Bołtacz-Rzepkowska, E. The effect of dental anxiety on the dental status of adult patients in the Lodz region. Dent. Med. Probl. 2017, 26, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, L.; Freeman, R.; Humphris, G. Why are people afraid of the dentist? Observations and Explanations. Med. Princ. Pract. 2014, 23, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiset, L.; Milgrom, P.; Weinstein, P.; Melnick, S. Common fears and their relationship to dental fear and utilization of the dentist. Anesth. Progr. 1989, 36, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczak-Zagalska, H.; Peplińska, M.; Emerich, K. Objective methods of assessing dental anxiety in children and adolescents. Ann. Acad. Medicae Gedanensis. 2014, 44, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, A.G.; Rodd, H.D.; Porritt, J.M.; Baker, S.R.; Creswell, C.; Newton, T.; Williams, C.; Marshman, Z. Children’s experiences of dental anxiety. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2017, 27, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krufczyk, M. Dentophobia—How to settle a terrified patient? Mag. Stomatol. 2011, 1, 76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dobros, K.; Hajto-Bryk, J.; Wnek, A.; Zarzecka, J.; Rzepka, D. The level of dental anxiety and dental status in adult patients. J. Int. Oral Health. 2014, 6, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Appukuttan, D.; Vinayagavel, M.; Tadepalli, A. Utility and validity of a single-item visual analog scale for measuring dental anxiety in clinical practice. J. Oral Sci. 2014, 56, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, S.R.; Alsa’di, A.G.; Taani, D.S. Factors influencing dental care access in Jordanian adults. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Łanowy, P.; Trzcionka, A.; Skaba, D.; Tanasiewicz, M. Gender related changes of empathy level among Polish dental students over the course of training. Medicine 2020, 99, e18470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brekalo-Prso, I.; Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Trzcionka, A.; Pezelj-Ribaric, S.; Paljevic, E.; Tanasiewicz, M.; Persic-Bukmir, R. Empathy amongst dental students: An institutional cross-sectional survey in poland and croatia. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 24, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Trzcionka, A.; Doniec, R.J.; Sieciński, S.; Tanasiewicz, M. The influence of gender and year of study on stress levels and coping strategies among polish dental. Medicine 2020, 56, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocny-Pachońska, K.; Doniec, R.J.; Trzcionka, A.; Pachoński, M.; Piaseczna, N.; Sieciński, S.; Osadcha, O.; Łanowy, P.; Tanasiewicz, M. Evaluating the stress-response of dental students to the dental school environment. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leutgeb, V.; Übel, S.; Schienle, A. Can you read my pokerface? A study on sex differences in dentophobia. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2013, 121, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, C.A.; Newton, T.; Milgrom, P. Who is referred for sedation for dentistry and why? Br. Dent. J. 2009, 206, E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Humphris, G.M.; King, K. The prevalence of dental anxiety across previous distressing experiences. J. Anxiety Disord. 2011, 25, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeddy, N.; Nithya, S.; Radhika, T.; Jeddy, N. Dental anxiety and influencing factors: A cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey. Indian. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 29, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- van Wijk, A.; Makkes, P. Highly anxious dental patients report more pain during dental injections. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 205, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Wijk, A.J.; Hoogstraten, J. The Fear of Dental Pain questionnaire: Construction and validity. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 2003, 111, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Number of Respondents (% of Respondents) | Number of Women (% of Respondents) | Number of Men (% of Respondents) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 83 (63.9%) | 35 (26.9%) | 48 (36.9%) |

| 25–34 | 26 (20%) | 17 (12.9%) | 9 (6.9%) |

| 35–44 | 14 (10.7%) | 10 (7.7%) | 4 (3.0%) |

| 45–54 | 7 (5.4%) | 4 (3.0%) | 3 (2.3%) |

| >55 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| In total: | 130 | 66 (50.8%) | 64 (49.2%) |

| Year of Studies in the Field of Dentistry | Women (% of All Students) | Man (% of All Students) | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 11 (10.8%) | 3 (2.9%) | 14 (13.7%) |

| 2nd | 21 (20.6%) | 8 (7.8%) | 29 (28.4%) |

| 3rd | 25 (24.5%) | 8 (7.8%) | 33 (32.3%) |

| 4th | 13 (12.7% | 5 (4.9%) | 18 (17.6%) |

| 5th | 7 (6.9%) | 1 (0.9%) | 8 (7.8%) |

| In total: | 77 (75.5%) | 25 (24.5%) | 102 |

| The Date of the Last Visit | % Women | % Men | % Female Dental Students | % Male Dental Students | % Total |

| Up to 6 months ago | 51.6% | 60.6% | 81.8% | 76.0% | 67.1% |

| 6–12 months ago | 19.3% | 24.6% | 15.6% | 8.0% | 18.2% |

| Over a year ago | 22.6% | 9.8% | 2.6% | 12.0% | 11.1% |

| Over a two years ago | 6.4% | 4.9% | 0 | 4.0% | 3.6% |

| The Frequency of Visits | |||||

| Once every 6 months | 19.4% | 32.8% | 67.5% | 52.0% | 43.1% |

| Once a year | 41.9% | 29.5% | 27.3% | 20.0% | 31.1% |

| Once every two years | 19.4% | 19.7% | 2.6% | 16.0% | 13.3% |

| Once every 3 years or more seldom | 6.4% | 4.9% | 0 | 0 | 3.1% |

| Lack of visits | 12.9% | 13.1% | 2.6% | 12.0% | 9.3% |

| The Reason for the Visit | |||||

| Check-up visit | 43.5% | 55.7% | 62.3% | 44.0% | 53.3% |

| Hygienic treatment | 6.4% | 4.9% | 24.8% | 20.0% | 13.8% |

| Toothache | 32.3% | 32.8% | 7.8% | 20.0% | 22.8% |

| Periodontal problems | 6.4% | 1.6% | 0 | 0 | 2.2% |

| Making dentures | 3.2% | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9% |

| Teeth extractions | 3.2% | 0 | 2.6% | 0 | 1.8% |

| Other disturbing conditions | 4.8% | 4.9% | 2.6% | 16.0% | 5.3% |

| The Date of the Last Visit | % Women | % Men | % Female Dental Students | % Male Dental Students | % Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bad past experience of pain sensation during treatment | 66.1% | 52.5% | 77.9% | 84.0% | 68.4% |

| Anxiety caused by the sound of a drill or other apparatus | 16.1% | 18.0% | 14.3% | 4.0% | 14.7% |

| Unpleasant smell of the dentist’s office | 1.6% | 3.3% | 1.3% | 4.0% | 2.2% |

| Deprived of empathy, rude and unreliable doctor | 1.6% | 8.2% | 5.2% | 4.0% | 4.9% |

| Shame caused by the condition of the teeth | 9.7% | 3.3% | 1.3 | 0 | 4.0% |

| Do not know what dentophobia is | 4.8% | 14.7% | 0 | 4.0% | 5.8% |

| The Triggering Factor of Anxiety | % Women | % Men | % Female Dental Students | % Male Dental Students | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The pain itself | 33.9% | 26.2% | 33.9% | 26.2% | 30.2% |

| The sound of dental equipment | 8.0% | 16.4% | 8.1% | 16.4% | 8.9% |

| Crossing the threshold of a dentist’s office | 17.7% | 8.2% | 17.7% | 8.2% | 7.1% |

| Root canal treatment | 11.3% | 3.3% | 11.3% | 3.3% | 6.2% |

| The moment of administration of anesthesia or its absence | 6.4% | 1.6% | 6.4% | 1.6% | 4.9% |

| Tooth extraction | 3.2% | 8.2% | 3.2% | 8.2% | 4.9% |

| Tooth root resection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I am not afraid of treatment | 19.3% | 36.1% | 19.3% | 36.1% | 36.4% |

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| In your opinion, is it helpful for the patient to overcome the fear of visiting a dentist by explaining what the procedure will involve and what it aims to do? | Yes 87.1% No 12.9% | Yes 98.4% No 1.6% |

| Does building a good doctor–patient relationship have a great impact on overcoming the fear of visiting a dentist’s office? | Yes 79.0% No 20.9% | Yes 83.6% No 16.4% |

| Scale | Women | Men | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0—no feeling of stress or fear | 17 (27.4%) | 28 (45.9%) | 45 (36.6%) |

| 1—anxiety, nervousness | 22 (35.5%) | 19 (29.5%) | 41 (33.3%) |

| 2—nervousness | 5 (8.0%) | 3 (4.9%) | 9 (7.3%) |

| 3—nervousness (trembling hands, stress at the thought of visiting) | 10 (16.1%) | 3 (4.9%) | 13 (10.6%) |

| 4—fear with symptoms (e.g., stomach aches and headaches) | 6 (9.7%) | 5 (8.2%) | 11 (8.9%) |

| 5—long-term fear that makes it impossible to visit | 2 (3.2%) | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (3.2%) |

| Scale | Female Dental Students | Male Dental Students | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0—no feeling of stress or fear | 46 (45.1%) | 10 (9.8%) | 56 (54.9%) |

| 1—anxiety, nervousness | 24 (23.5%) | 11 (10.8%) | 35 (34.3%) |

| 2—nervousness | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (1.9%) | 5 (4.9%) |

| 3—nervousness (trembling hands, stress at the thought of visiting) | 3 (2.9%) | 1 (1.0%) | 4 (3.9%) |

| 4—fear with symptoms (e.g., stomach aches and headaches) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (1.9%) |

| 5—long-term fear that makes it impossible to visit | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Furgała, D.; Markowicz, K.; Koczor-Rozmus, A.; Zawilska, A. Causes and Severity of Dentophobia in Polish Adults—A Questionnaire Study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070819

Furgała D, Markowicz K, Koczor-Rozmus A, Zawilska A. Causes and Severity of Dentophobia in Polish Adults—A Questionnaire Study. Healthcare. 2021; 9(7):819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070819

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurgała, Dominika, Kinga Markowicz, Aleksandra Koczor-Rozmus, and Anna Zawilska. 2021. "Causes and Severity of Dentophobia in Polish Adults—A Questionnaire Study" Healthcare 9, no. 7: 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070819

APA StyleFurgała, D., Markowicz, K., Koczor-Rozmus, A., & Zawilska, A. (2021). Causes and Severity of Dentophobia in Polish Adults—A Questionnaire Study. Healthcare, 9(7), 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070819