Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in Peru: Psychological Distress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

2.2. Instruments and Data Collection

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Principles

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

3.2. Psychological Distress in the Sample Studied

3.3. Sociodemographic Data and Psychological Distress

3.4. Physical Symptoms, Health-Related Variables, and Psychological Distress

3.5. Contact History and Psychological Distress

3.6. Preventive Measures and Psychological Distress

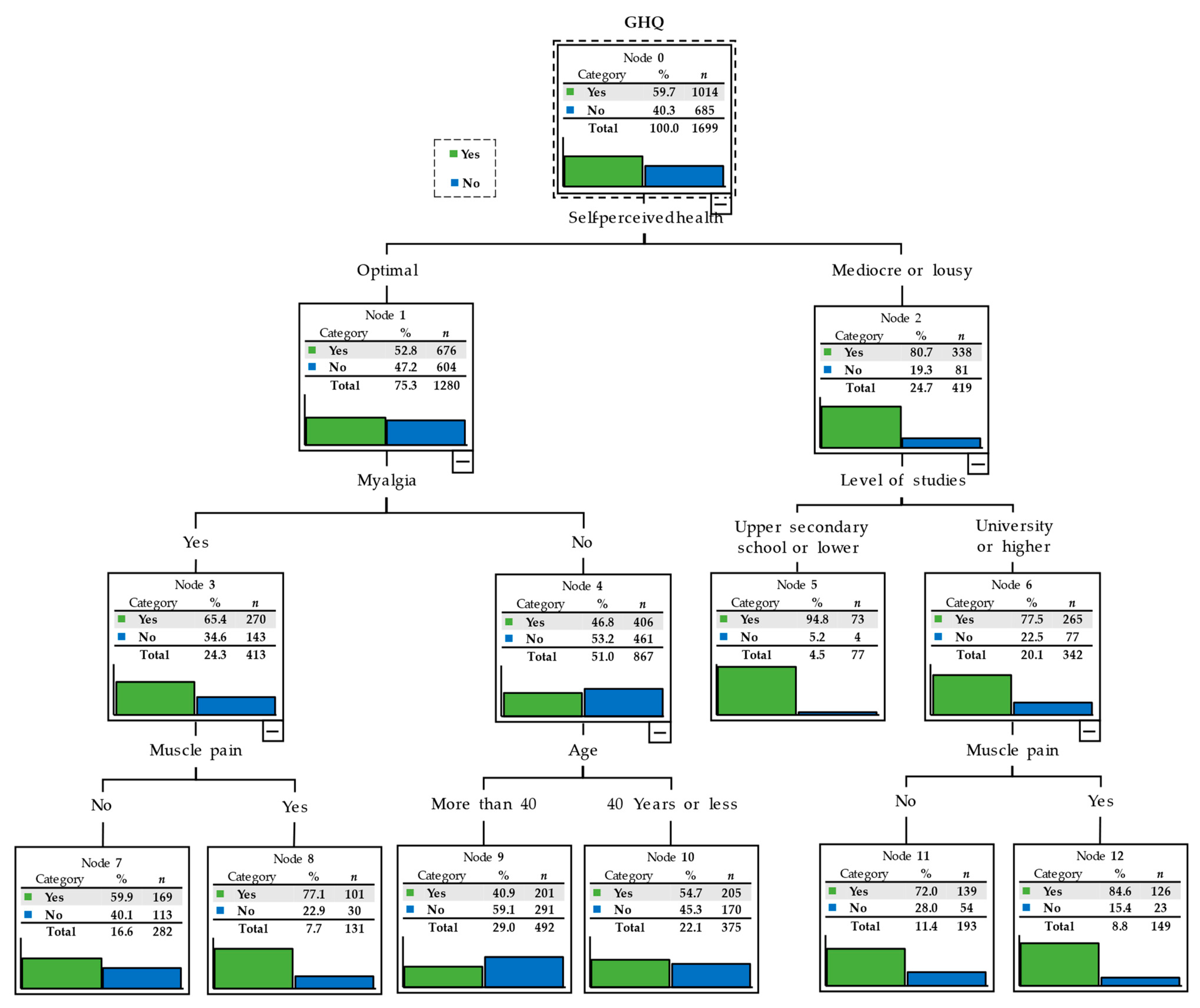

3.7. Segmentation Tree Displaying the Level of Psychological Distress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization/Europe International Health Regulations—2019-nCoV Outbreak is An Emergency of Interna-tional Concern. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 14 March 2020).

- World Health Organization. WHO Announces COVID-19 Outbreak a Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Ashktorak, H.; Pizuomo, A.; González, N.A.F.; Villagrana, E.D.C.; Herrera-Solís, M.E.; Cardenas, G.; Zavala-Alvarez, D.; Oskrochi, G.; Awoyemi, E.; Adeleye, F.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of COVID-19 Impact in Latin America. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, L.; D’Orsogna, M.R.; Chou, T. Using excess deaths and testing statistics to improve estimates of COVID-19 mortalities. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, C.M. Reflexiones sobre el COVID-19, el Colegio Médico del Perú y la Salud Pública. [Reflections on COVID-19 infection, Peru Medical College and the Public Health]. Acta Med. Peru. 2020, 37, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, E. Coronavirus: Esta es la cronología del COVID-19 en el Perú y el mundo. Lima; RPP Noticias. 7 April 2020. Available online: https://rpp.pe/vital/salud/coronavirus-esta-es-la-cronologia-del-covid-19-en-el-peru-y-el-mundo-noticia-1256724 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. Ministerio de Salud de Perú. Brotes, Epizootias y otros Reportes de Salud. 2020. Available online: https://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/rumores/2020/Reporte_030-2020.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Johns Hopkings Coronavirus Resource Center. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- World Health Organization. COVID 19 Global. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/region/amro/country/pe (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- United Nations. Shared Responsibility Global Solidarity: Responding to the Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-03/SG-Report-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Covid19.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Decreto Supremo que prorroga el Estado de Emergencia Nacional por las graves circunstancias que afectan la vida de la Nación a consecuencia de la COVID-19 y modifica el Decreto Supremo Nº 184-2020-PCM. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-supremo-que-prorroga-el-estado-de-emergencia-naciona-decreto-supremo-n-201-2020-pcm-1914076-2/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Decreto de Urgencia que dicta Medidas Complementarias y Extraordinarias para Reforzar la Respuesta Sanitaria en el Marco de la Emergencia Nacional por el COVID-19. Available online: https://busquedas.elperuano.pe/normaslegales/decreto-de-urgencia-que-dicta-medidas-complementarias-y-extr-decreto-de-urgencia-n-001-2021-1918572-1/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Cañari-Casaño, J.L.; Elorreaga, O.A.; Cochachin-Henostroza, O.; Huaman-Gil, S.; Dolores-Maldonado, G.; Aquino-Ramirez, A.; Giribaldi-Sierralta, J.P.; Aparco, J.P.; Antiporta, D.A.; Penny, M. Social predictors of food insecurity during the stay-at-home order due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru. Results from a cross-sectional web-based survey. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Valle, A. Public health matters: Why is Latin America struggling in addressing the pandemic? J. Public Health Policy 2021, 42, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolución Ministerial N° 972-2020-MINSA. Lineamientos para la Vigilancia, Prevención y Control de la Salud por Exposi-ción Al SARS-CoV-2. 2020. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/normas-legales/1366422-972-2020-minsa (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Bermejo-Martins, E.; Luis, E.; Sarrionandia, A.; Martínez, M.; Garcés, M.; Oliveros, E.; Cortés-Rivera, C.; Belintxon, M.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Different Responses to Stress, Health Practices, and Self-Care during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Stratified Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Andrés-Villas, M.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Díaz-Milanés, D.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Related Health Factors of Psychological Distress during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaronidis, J.; Mok, J.; Balogun, N.; Magee, C.G.; Omar, R.Z.; Carnemolla, A.; Batterham, R.L. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in people with an acute loss in their sense of smell and/or taste in a community-based population in London, UK: An observational cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, J.C.; Novoa, D.J.; Gómez, C.C.; Moreno, J.M.; Vargas, L.; Pérez, J.; Millán, H.; Arango, Á.I. Prognostic factors in hospitalized patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection, Bogotá, Colombia. Biomedica 2020, 40 (Suppl. 2), 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronbichler, A.; Kresse, D.; Yoon, S.; Lee, K.H.; Effenberger, M.; Shin, J.I. Asymptomatic patients as a source of COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 98, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Gu, X.; Kang, L.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. Lancet 2021, 397, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T.J.; Mohiddin, S.A.; DiMarco, A.; Patel, V.; Savvatis, K.; Marelli-Berg, F.M.; Madhur, M.S.; Tomaszewski, M.; Maffia, P.; D’Acquisto, F.; et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: Implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 1666–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Xu, M.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Dong, W. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: A single-centre longitudinal study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Lecca, L.I.; Alessio, F.; Finstad, G.L.; Bondanini, G.; Lulli, L.G.; Arcangeli, G.; Mucci, N. COVID-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization and the International Labour Office. Occupational Safety and Health in Public Health Emergen-cies: A Manual for Protecting Health Workers and Responders. Geneva. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275385/9789241514347-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Khonsari, N.M.; Shafiee, G.; Zandifar, A.; Poornami, S.M.; Ejtahed, H.-S.; Asayesh, H.; Qorbani, M. Comparison of psychological symptoms between infected and non-infected COVID-19 health care workers. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Lim, D.Y.; Chee, K.T. Not all trauma is the same. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 25200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.; Bansal, S.; Goyal, S.; Garg, A.; Sethi, N.; Pothiyill, D.I.; Sreelakshmi, E.S.; Sayyad, M.G.; Sethi, R. Psychological impact of mass quarantine on population during pandemics—The COVID-19 Lock-Down (COLD) study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud de Perú. Resolución 363-2020 MINSA, de 5 de junio. Documento técnico: Plan de salud Mental, en el contexto de Covid-19, Perú 2020–2021. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/804253/RM_363-2020-MINSA.PDF (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Glowacz, F.; Schmits, E. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdown: The young adults most at risk. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Chen, J.-H.; Xu, Y.-F. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquina-Lujan, R.J.; Adriazola-Casas, R. Autopercepción del estrés del personal de salud en primera línea de atención de pacientes con Covid-19 en Lima Metropolitana, Perú. ACC CIETNA 2020, 7, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud de Perú. Dirección General de Intervenciones Estratégicas en Salud Pública. Dirección de Salud Mental. Guía técnica para el cuidado de la salud mental del personal de la salud en el contexto del COVID-19 (R.M. N° 180-2020-MINSA). Lima: Ministerio de Salud. 2020. Available online: http://bvs.minsa.gob.pe/local/MINSA/5000.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Saravia-Bartra, M.M.; Cazorla-Saravia, P.; Cedillo-Ramirez, L. Anxiety level of first-year medical students from a private university in Peru in times of Covid-19. Rev. Fac. Med. Hum. 2020, 20, 568–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovón Cueva, M.A.; Cisneros Terrones, S.A. Repercusiones de las clases virtuales en los estudiantes universitarios en el con-texto de la cuarentena por COVID-19: El caso de la PUCP. Propósitos y Representaciones 2020, 8, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArunKumar, K.; Kalaga, D.V.; Kumar, C.M.S.; Chilkoor, G.; Kawaji, M.; Brenza, T.M. Forecasting the dynamics of cumulative COVID-19 cases (confirmed, recovered and deaths) for top-16 countries using statistical machine learning models: Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and Seasonal Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (SARIMA). Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 103, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Martín-Pereira, J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Martínez-Riera, J.R.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Impacto del SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) en la salud mental de los profesionales sanitarios: Una revisión sistemática [Impact of SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) on the mental health of healthcare professionals: A systematic review.]. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2020, 94, e202007088. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D.P.; Gater, R.; Sartorius, N.; Ustun, T.B.; Piccinelli, M.; Gureje, O.; Rutter, C. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Living, Working and COVID-19, COVID-19 Series; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino, C.; Ausín, B.; Castellanos, M.Á.; Saiz, J.; López-Gómez, A.; Ugidos, C.; Muñoz, M. Mental health conse-quences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Follow or not follow?: The relationship between psychological entitlement and compliance with preventive measures to the COVID-19. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 174, 110678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenstone, Michael and Nigam, Vishan, Does Social Distancing Matter? (March 30, 2020). University of Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics Working Paper No. 2020-26. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561244 (accessed on 12 February 2021). [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Salas, S.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Andrés-Villas, M.; Díaz-Milanés, D.; Romero-Martín, M.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Psycho-Emotional Approach to the Psychological Distress Related to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: A Cross-Sectional Observational Study. Healthcare 2020, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Dias, A.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Health-related factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among non-health workers in Spain. Saf. Sci. 2021, 133, 104996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques-Aviñó, C.; López-Jiménez, T.; Medina-Perucha, L.; De Bont, J.; Gonçalves, A.Q.; Duarte-Salles, T.; Berenguera, A. Gender-based approach on the social impact and mental health in Spain during COVID-19 lockdown: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e044617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, N.E.; El Ayadi, A.M. A call for a gender-responsive, intersectional approach to address COVID-19. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bann, D.; Villadsen, A.; Maddock, J.; Hughes, A.; Ploubidis, G.B.; Silverwood, R.J.; Patalay, P. Changes in the behavioural determinants of health during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: Gender, socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in 5 British cohort studies. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, T.; Grey, I. Health behaviour changes during COVID-19 and the potential consequences: A mini-review. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownson, R.C.; Seiler, R.; Eyler, A.A. Measuring the impact of public health policys. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A77. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broucke, S. Why health promotion matters to the COVID-19 pandemic, and vice versa. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Chee, K.T.; De Deyn, M.L.Z.Q.; Chua, Z. Staying connected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 519–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.L.D. Does culture matter social distancing under the COVID-19 pandemic? Saf. Sci. 2020, 130, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, S.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Domínguez-Gómez, J.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. People of African Descent of the Americas, Racial Discrimination, and Quality of the Health Services. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Exploring the association between compliance with measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and big five traits with Bayesian generalized linear model. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 176, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-La-Torre, G.E.; Rakib, R.J.; Pizarro-Ortega, C.I.; Dioses-Salinas, D.C. Occurrence of personal protective equipment (PPE) associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along the coast of Lima, Peru. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 774, 145774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Granero-Molina, J.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Dobarrio-Sanz, I.; López-Rodríguez, M.M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Correa-Casado, M.; Fernández-Sola, C. Design and Psychometric Analysis of the COVID-19 Prevention, Recognition and Home-Management Self-Efficacy Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, O.; Martiny, D.; Rochas, O.; van Belkum, A.; Kozlakidis, Z. Considerations for diagnostic COVID-19 tests. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirmiya, K.; Yakirevich-Amir, N.; Preis, H.; Lotan, A.; Atzil, S.; Reuveni, I. Women’s Depressive Symptoms during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Pregnancy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochaiwong, S.; Ruengorn, C.; Awiphan, R.; Ruanta, Y.; Boonchieng, W.; Nanta, S.; Kowatcharakul, W.; Pumpaisalchai, W.; Kanjanarat, P.; Mongkhon, P.; et al. Mental health circumstances among health care workers and general public under the pandemic situation of COVID-19 (HOME-COVID-19). Medicine 2020, 99, e20751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Allande-Cussó, R.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; García-Iglesias, J.; Coronado-Vázquez, V.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Design of Fear and Anxiety of COVID-19 Assessment Tool in Spanish Adult Population. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GHQ Total (n = 1699) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Yes (n = 1014) | No (n = 685) | χ2 | p | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval at the 95 Level) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 744 (43.8) | 53.0 | 47.0 | 24.879 | <0.001 | 0.608 |

| Female | 955 (56.2) | 64.9 | 35.1 | (0.500, 0.740) | ||

| Age * | ||||||

| 40 years old or younger | 868 (51.5) | 65.7 | 34.3 | 26.186 | <0.001 | 1.667 |

| Older than 40 | 816 (48.5) | 53.4 | 46.6 | (1.370, 2.029) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Without a partner | 879 (51.7) | 63.4 | 36.6 | 10.279 | 0.001 | 1.374 |

| With a partner | 820 (48.3) | 55.7 | 44.3 | (1.131, 1.669) | ||

| Level of studies | ||||||

| Upper secondary school or lower | 239 (14.1) | 68.2 | 31.8 | 8.388 | 0.004 | 1.535 |

| University or higher | 1460 (85.9) | 58.3 | 41.7 | (1.147, 2.054) | ||

| You are ** | ||||||

| Self-employed | 119 (7.0) | 58.0 | 42.0 | 1.541 | 0.463 | |

| Public worker | 579 (34.1) | 55.4 | 44.6 | |||

| Private-company worker | 390 (23.0) | 52.3 | 47.7 | |||

| Children | ||||||

| Yes | 975 (57.4) | 55.1 | 44.9 | 20.166 | <0.001 | 0.635 |

| No | 724 (42.6) | 65.9 | 34.1 | (0.520, 0.775) | ||

| Pet | ||||||

| Yes | 937 (55.2) | 59.7 | 40.3 | 0.000 | 0.982 | 1.002 |

| No | 762 (44.9) | 59.7 | 40.3 | (0.825, 1.218) | ||

| Disability | ||||||

| Yes | 86 (5.1) | 69.8 | 30.2 | 3.829 | 0.050 | 1.594 |

| No | 1613 (94.9) | 59.1 | 40.9 | (0.996, 2.553) | ||

| Confinement | ||||||

| Strict | 646 (38.0) | 62.2 | 37.8 | 9.040 | 0.029 | |

| Except purchase or work | 959 (56.4) | 59.1 | 40.9 | |||

| No | 42 (2.5%) | 40.5 | 59.5 | |||

| Other situation | 52 (3.1%) | 53.8 | 46.2 | |||

| Total (n = 1699) | |

|---|---|

| Item | M (SD) |

| 1. Have you been able to properly concentrate on what you were doing? | 2.48 (0.73) |

| 2. Have your worries made you lose a lot of sleep? | 2.51 (0.96) |

| 3. Have you felt you are developing a relevant role in life? | 1.94 (0.86) |

| 4. Have you felt capable of making decisions? | 1.98 (0.78) |

| 5. Have you felt constantly overwhelmed and stressed? | 2.64 (0.92) |

| 6. Have you felt unable to overcome your difficulties? | 2.10 (0.91) |

| 7. Have you been able to develop your normal daily activities? | 2.60 (0.86) |

| 8. Have you been able to properly face your difficulties? | 2.20 (0.73) |

| 9. Have you felt unhappy or depressed? | 2.26 (0.98) |

| 10. Have you lost confidence in yourself? | 1.69 (0.91) |

| 11. Have you thought that you are a worthless person? | 1.28 (0.67) |

| 12. Do you feel reasonably happy given the circumstances? | 2.10 (0.77) |

| GHQ-12 (Score on a scale of 12) | 4.18 (3.52) |

| Cut-off point ≥ 3 | n (%) |

| Yes | 1014 (59.7) |

| No | 685 (40.3) |

| Total (n = 1699) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHQ | ||||||

| N (%) | Yes (n = 1014) | No (n = 685) | χ2 | p | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval at the 95 Level) | |

| Physical Symptoms | ||||||

| Fever | ||||||

| Yes | 57 (3.4) | 87.7 | 12.3 | 19.267 | <0.001 | 5.024 |

| No | 1642 (96.6) | 58.7 | 41.3 | (2.264, 11,147) | ||

| Cough | ||||||

| Yes | 297 (17.5) | 71.7 | 28.3 | 21.665 | <0.001 | 1.903 |

| No | 1402 (82.5) | 57.1 | 42.9 | (1.447, 2.502) | ||

| Myalgia | ||||||

| Yes | 647 (38.1) | 72.8 | 27.2 | 74.697 | <0.001 | 2.509 |

| No | 1052 (61.9) | 51.6 | 48.4 | (2.031, 3.098) | ||

| Muscle pain | ||||||

| Yes | 425 (25.0) | 74.4 | 25.6 | 50.696 | <0.001 | 2.392 |

| No | 1274 (75.0) | 54.8 | 45.2 | (1.874, 3.054) | ||

| Dizziness | ||||||

| Yes | 176 (10.4) | 77.8 | 22.2 | 26.905 | <0.001 | 2.588 |

| No | 1523 (89.6) | 57.6 | 42.4 | (1.787, 3.746) | ||

| Diarrhea | ||||||

| Yes | 198 (11.7) | 72.2 | 27.8 | 14.647 | <0.001 | 1.881 |

| No | 1501 (88.3) | 58.0 | 42.0 | (1.355, 2.609) | ||

| Sore throat | ||||||

| Yes | 415 (24.4) | 68.9 | 31.1 | 19.457 | <0.001 | 1.693 |

| No | 1284 (75.6) | 56.7 | 43.3 | (1.338, 2.143) | ||

| Rhinitis | ||||||

| Yes | 466 (27.4) | 66.5 | 33.5 | 12.490 | <0.001 | 1.493 |

| No | 1233 (72.6) | 57.1 | 42.9 | (1.195, 1.866) | ||

| Chills | ||||||

| Yes | 128 (7.5) | 73.4 | 26.6 | 10.885 | 0.001 | 1.956 |

| No | 1571 (92.5) | 58.6 | 41.4 | (1.305, 2.933) | ||

| Shortness of breath | ||||||

| Yes | 100 (5.9) | 80.0 | 20.0 | 18.229 | <0.001 | 2.848 |

| No | 1599 (94.1) | 58.4 | 41.6 | (1.727, 4.695) | ||

| Current Health Status | ||||||

| Self-perceived health | ||||||

| Optimal | 1280 (75.3) | 52.8 | 47.2 | 101.793 | <0.001 | 0.268 |

| Mediocre or lousy | 419 (24.7) | 80.7 | 19.3 | (0.206, 0.350) | ||

| Chronic illness | ||||||

| Yes | 490 (28.8) | 62.9 | 37.1 | 2.885 | 0.089 | 1.206 |

| No | 1209 (71.2) | 58.4 | 41.6 | (0.972, 1.497) | ||

| Currently taking medication | ||||||

| Yes | 465 (27.4) | 65.2 | 34.8 | 7.988 | 0.005 | 1.376 |

| No | 1234 (72.63) | 57.6 | 42.4 | (1.102, 1.717) | ||

| Admitted to hospital last 14 days | ||||||

| Yes | 9 (0.5) | 77.8 | 22.2 | * | 0.328 | 2.374 |

| No | 1690 (99.5) | 59.6 | 40.4 | (0.492, 11.462) | ||

| Medical care last 14 days | ||||||

| Yes | 90 (5.3) | 74.4 | 25.6 | 8.607 | 0.003 | 2.036 |

| No | 1609 (94.7) | 58.9 | 41.1 | (1.255, 3.304) | ||

| Total (n = 1699) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHQ | ||||||

| N (%) | Yes (n = 1014) | No (n = 685) | χ2 | p | Odds Ratio (Confidence Interval at the 95 Level) | |

| Contact > 15′ < 2 m with infected person | ||||||

| Yes, or doesn’t know | 567 (33.4) | 63.7 | 36.3 | 5.620 | 0.018 | 1.285 |

| No | 1132 (66.6) | 57.7 | 42.3 | (1.044, 1.582) | ||

| Casual contact with infected person | ||||||

| Yes, or doesn’t know | 657 (38.7) | 63.3 | 36.7 | 5.886 | 0.015 | 1.282 |

| No | 1042 (61.3) | 57.4 | 42.6 | (1.049, 1.566) | ||

| Contact with person or material suspected of being infected | ||||||

| Yes, or doesn’t know | 736 (43.3) | 62.5 | 37.5 | 4.285 | 0.038 | 1.230 |

| No | 963 (56.7) | 57.5 | 42.5 | (1.011, 1.498) | ||

| Infected family member | ||||||

| Yes, or doesn’t know | 333 (19.6) | 6.6 | 32.4 | 10.703 | 0.001 | 1.524 |

| No | 1366 (80.4) | 57.8 | 42.2 | (1.183, 1.963) | ||

| Has been performed diagnostic test | ||||||

| Yes | 223 (13.1) | 60.1 | 39.9 | 0.018 | 0.894 | 1.020 |

| No | 1476 (86.9) | 59.6 | 40.4 | (0.765, 1.359) | ||

| TOTAL (n = 1699) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHQ | |||||

| M (SD) | Yes | No | Statistical | p | |

| Covering mouth | 4.52 (0.73) | 4.49 (0.74) | 4.57 (0.72) | −2.310 | 0.021 |

| Avoiding sharing utensils | 3.96 (1.30) | 3.92 (1.31) | 4.01 (1.28) | −1.382 | 0.167 |

| Washing hands with soap and water | 4.77 (0.50) | 4.75 (0.52) | 4.80 (0.49) | −2.112 | 0.035 |

| Washing hands with hydroalcoholic solution | 4.00 (1.03) | 3.97 (1.03) | 4.04 (1.03) | −1.364 | 0.173 |

| Washing hands immediately after coughing, touching the nose, or sneezing | 4.06 (1.02) | 3.96 (1.07) | 4.20 (0.93) | −4.830 | <0.001 |

| Washing hands after touching potentially contaminated objects | 4.62 (0.68) | 4.61 (0.68) | 4.63 (0.68) | −0.766 | 0.444 |

| Wearing a mask regardless of the presence of symptoms | 4.48 (0.93) | 4.45 (0.95) | 4.53 (0.91) | −1.705 | 0.088 |

| Keeping at least a metre and a half distance between others | 4.51 (0.71) | 4.48 (0.73) | 4.56 (0.68) | −2.385 | 0.017 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Palomino-Baldeón, J.C.; Ortega-Moreno, M.; Villavicencio-Guardia, M.d.C.; Dias, A.; Bernardes, J.M.; Gómez-Salgado, J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in Peru: Psychological Distress. Healthcare 2021, 9, 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060691

Ruiz-Frutos C, Palomino-Baldeón JC, Ortega-Moreno M, Villavicencio-Guardia MdC, Dias A, Bernardes JM, Gómez-Salgado J. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in Peru: Psychological Distress. Healthcare. 2021; 9(6):691. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060691

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Frutos, Carlos, Juan Carlos Palomino-Baldeón, Mónica Ortega-Moreno, María del Carmen Villavicencio-Guardia, Adriano Dias, João Marcos Bernardes, and Juan Gómez-Salgado. 2021. "Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in Peru: Psychological Distress" Healthcare 9, no. 6: 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060691

APA StyleRuiz-Frutos, C., Palomino-Baldeón, J. C., Ortega-Moreno, M., Villavicencio-Guardia, M. d. C., Dias, A., Bernardes, J. M., & Gómez-Salgado, J. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in Peru: Psychological Distress. Healthcare, 9(6), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060691