Effectiveness of Antipsychotics in Reducing Suicidal Ideation: Possible Physiologic Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Selection

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

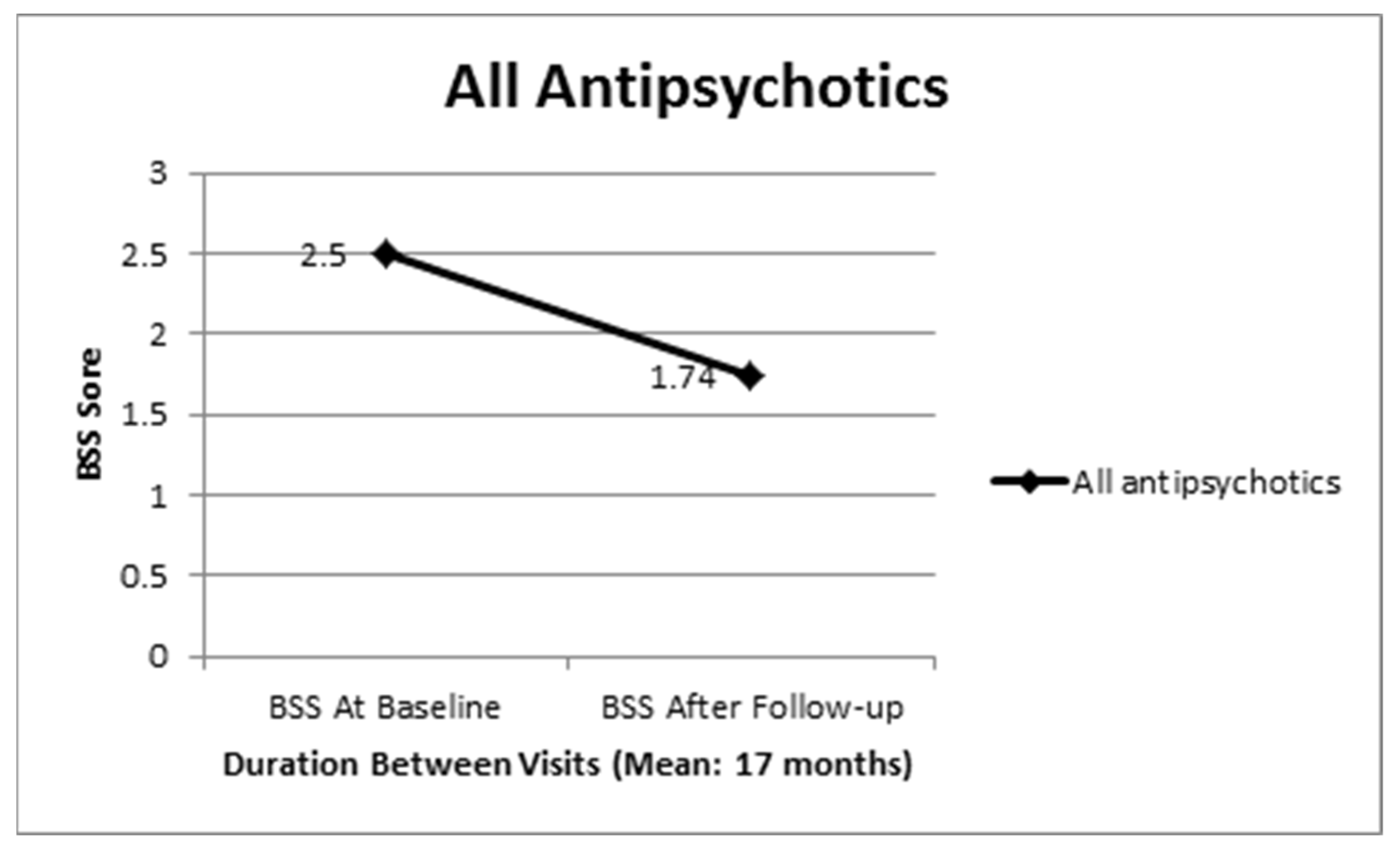

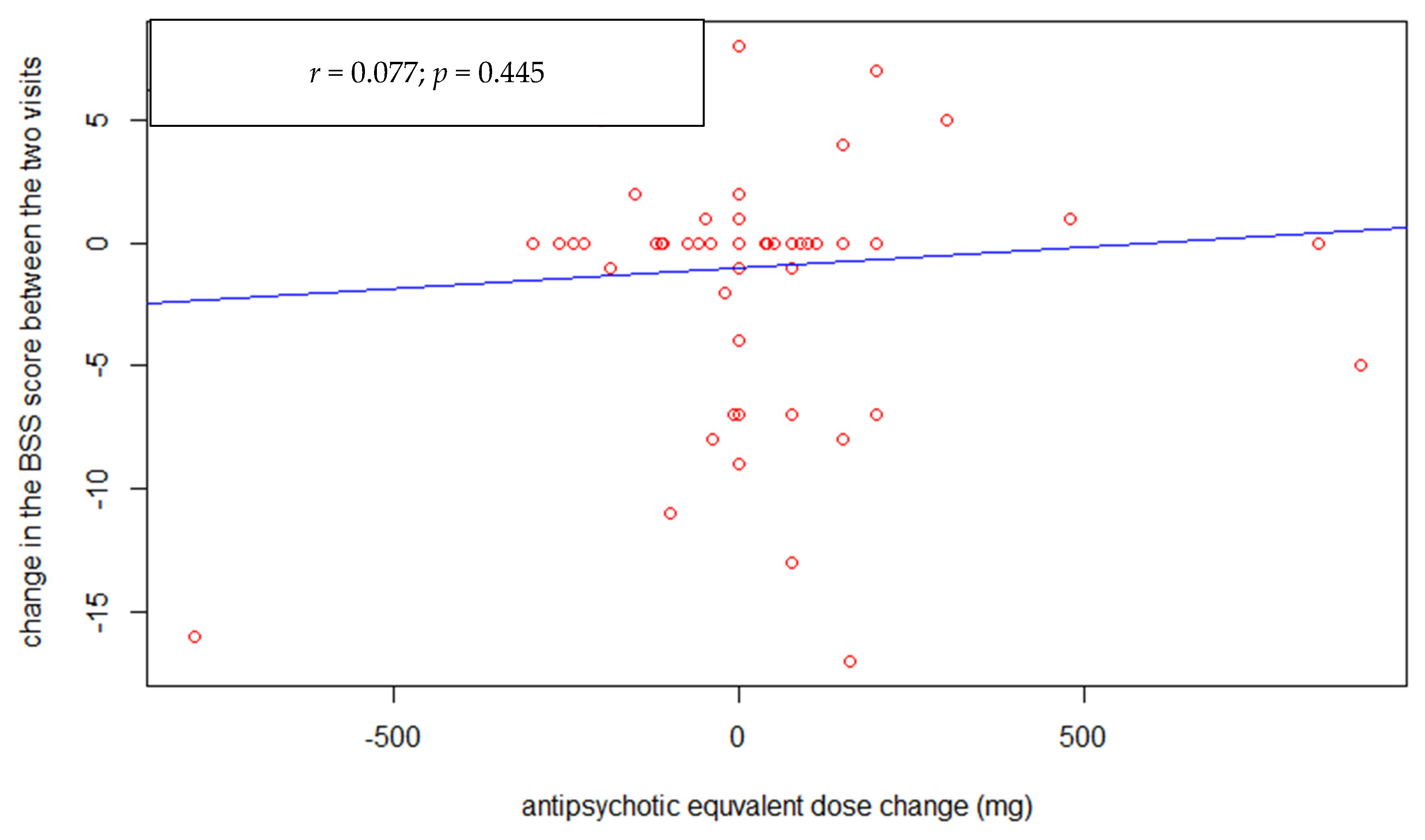

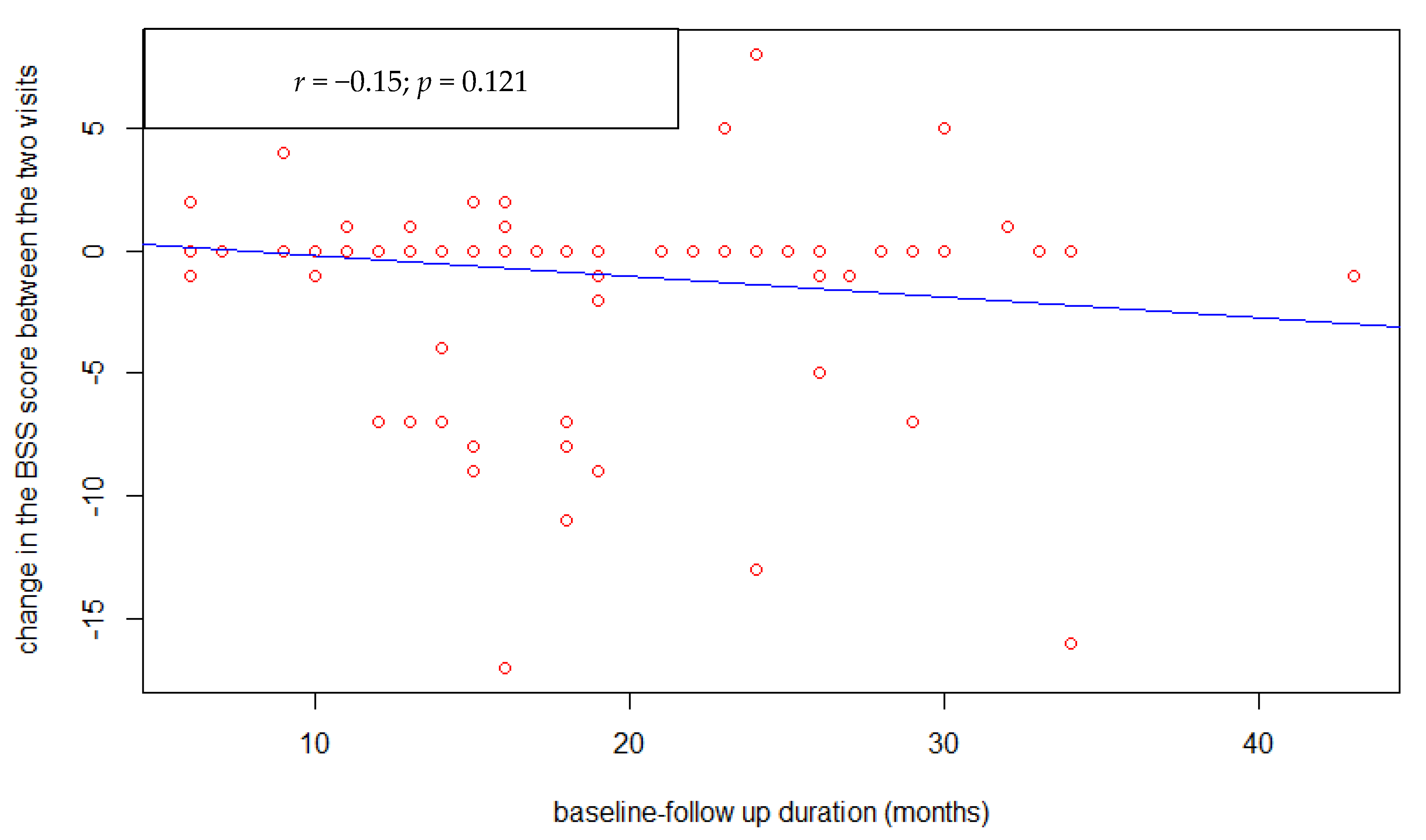

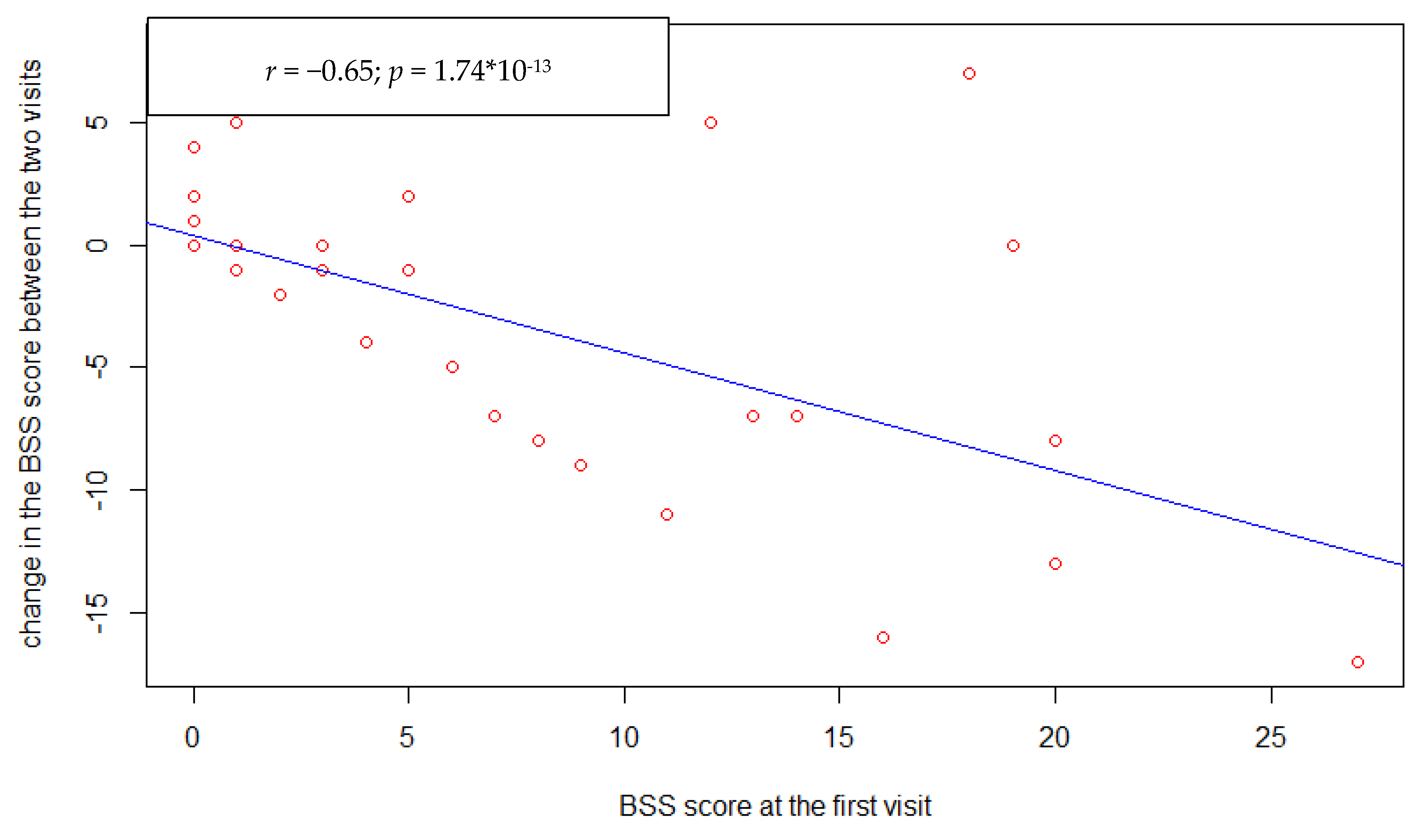

3. Results

3.1. Comparison between Clozapine and Other Antipsychotics

3.2. Comparison between Long-Acting Injectable and Oral Antipsychotics

3.3. Comparison between Typical and Atypical Antipsychotic Treatment

3.4. Comparison between Antipsychotic Treatment with Antidepressants Augmentation and Antipsychotic Treatment without Antidepressants Augmentation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSS | Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation |

| CAMH | Centre for Addiction and Mental Health |

| CPZe | Chlorpromazine Equivalent |

| DDD | Defined Daily Doses |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| RCT | Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial |

| SCID | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM disorders |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Palmer, B.A.; Pankratz, V.S.; Bostwick, J.M. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: A reexamination. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, K.; Taylor, M. Review: Suicide and schizophrenia: A systematic review of rates and risk factors. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 24 (Suppl. 4), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radomsky, E.D.; Haas, G.L.; Mann, J.J.; Sweeney, J.A. Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1590–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montross, L.P.; Kasckow, J.; Golshan, S.; Solorzano, E.; Lehman, D.; Zisook, S. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and concurrent subsyndromal depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2008, 196, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Black, D.W.; Arndt, S.; Hubbard, W.C.; Andreasen, N.C. Factors associated with suicide attempts among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 1998, 49, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.S.; Lai-Wan, C.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Tang, C.P.; Lin, F.R.; Li, L.; Conwell, Y. Mortality of geriatric and younger patients with schizophrenia in the community. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.S.; Nuechterlein, K.H.; Mintz, J.; Ventura, J.; Gitlin, M.; Liberman, R.P. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in recent-onset schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1998, 24, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVylder, J.E.; Lukens, E.P.; Link, B.G.; Lieberman, J.A. Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts Among Adults With Psychotic Experiences: Data From the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. Jama Psychiatry 2015, 72, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausz, M.; Müller-Thomsen, T.; Haasen, C. Suicide among schizophrenic adolescents in the long-term course of illness. Psychopathology 1995, 28, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.S.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Conwell, Y.; Chan, C.L.W.; Yip, P.S.; Xiang, M.Z.; Caine, E.D. Mortality in people with schizophrenia in rural China 10-year cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 190, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, R.E.; Gates, C.; Cotton, P.G.; Whitaker, A. Suicide among Schizophrenics: Who Is at Risk? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1984, 172, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaräisänen, A.; Miettunen, J.; Lauronen, E.; Räsänen, P.; Isohanni, M. Good school performance is a risk factor of suicide in psychoses: A 35-year follow up of the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 114, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugnoli, R.; Novick, D.; Haro, J.M.; Rossi, A.; Bortolomasi, M.; Frediani, S.; Borgherini, G. Risk factors for suicide behaviors in the observational schizophrenia outpatient health outcomes (SOHO) study. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trémeau, F.; Staner, L.; Duval, F.; Bailey, P.; Crocq, M.A.; Corrêa, H. Suicidal behavior in schizophrenia and family history of suicide. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2001, 3, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Family history of suicide. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1983, 40, 971–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiihonen, J.; Walhbeck, K.; Lönnqvist, J.; Klaukka, T.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Volavka, J.; Haukka, J. Effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of patients in community care after first hospitalisation due to schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: Observational follow-up study. BMJ 2006, 333, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.; Ishak, K.; Proskorovsky, I.; Caro, J. Compliance with refilling prescriptions for atypical antipsychotic agents and its association with the risks for hospitalization, suicide, and death in patients with schizophrenia in Quebec and Saskatchewan: A retrospective database study. Clin. Ther. 2006, 28, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, M.S.; Chan, C.L.W.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Mao, W.J.; Hu, S.H.; Tang, C.P.; Conwell, Y. Differences in mortality and suicidal behaviour between treated and never-treated people with schizophrenia in rural China. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 195, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.A.W.; Pasterski, G.; Ludlow, J.M.; Street, K.; Taylor, R.D.W. The discontinuance of maintenance neuroleptic therapy in chronic schizophrenic patients: Drug and social consequences. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasckow, J.; Felmet, K.; Zisook, S. Managing suicide risk in patients with schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 2011, 25, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zisook, S.; Kasckow, J.W.; Lanouette, N.M.; Golshan, S.; Fellows, I.; Vahia, I.; Rao, S. Augmentation with citalopram for suicidal ideation in middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder who have subthreshold depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innamorati, M.; Baratta, S.; Di Vittorio, C.; Lester, D.; Girardi, P.; Pompili, M.; Amore, M. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of depressive and psychotic symptoms in patients with chronic schizophrenia: A naturalistic study. Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2013, 423205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, H.Y.; Alphs, L.; Green, A.I.; Altamura, A.C.; Anand, R.; Bertoldi, A.; Potkin, S. Clozapine treatment for suicidality in schizophrenia: International suicide prevention trial (InterSePT). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.M.; Lanza, L.L.; Arellano, F.; Rothman, K.J. Mortality in current and former users of clozapine. Epidemiology 1997, 8, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, H.Y.; Okayli, G. Reduction of suicidality during clozapine treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia: Impact on risk-benefit assessment. Am. J. Psychiatry 1995, 152, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Modestin, J.; Dal Pian, D.; Agarwalla, P. Clozapine diminishes suicidal behavior: A retrospective evaluation of clinical records. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 66, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Correll, C.U.; Cohen, D. Do antipsychotic medications reduce or increase mortality in schizophrenia? A critical appraisal of the FIN-11 study. Schizophr. Res. 2010, 117, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sernyak, M.J.; Desai, R.; Stolar, M.; Rosenheck, R. Impact of clozapine on completed suicide. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC Classification Index with DDDs, 2015. Oslo 2014. Available online: https://www.whocc.no/ (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Gardner, D.M.; Murphy, A.L.; O’Donnell, H.; Centorrino, F.; Baldessarini, R.J. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- First, M.B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Gibbon, M.; Williams, J.B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P); Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A. Manual for Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, E.; Avenoso, A.; Scordo, M.G.; Ancione, M.; Madia, A.; Gatti, G.; Perucca, E. Inhibition of risperidone metabolism by fluoxetine in patients with schizophrenia: A clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interaction. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002, 22, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennen, J.; Baldessarini, R.J. Suicidal risk during treatment with clozapine: A meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 73, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age: mean (SD) | 44.4 (12.96) |

| Gender: male n (%) | 68 (66) |

| Ethnicity: White n (%) | 69 (67) |

| Marital status: married or common law n (%) | 6 (5.8) |

| Employment: employed n (%) | 38 (36.9) |

| Education: post-high school education n (%) | 62 (60.2) |

| Smokers: n (%) | 47 (45.6) |

| Lifetime drug or alcohol dependence: n (%) | 12 (11.7) |

| Past suicidal attempter: n (%) | 46 (44.7) |

| Average number of suicidal attempts: mean (SD) | 1.1 (2.1) |

| Subjects experiencing a Major Depression Episode: n (%) | 49 (47.6) |

| Family history of suicidal behavior: n (%) | 20 (19.6) |

| Atypical antipsychotics including clozapine: n (%) | 85 (85.9) |

| Clozapine users: n (%) | 28 (27.2) |

| Intramuscular injection: n (%) | 21 (20.4) |

| Augmenting antidepressants: n (%) | 29 (28.2) |

| Polypharmacy: n (%) | 16 (15.5) |

| Duration between the two visits in months: mean (SD) | 17.4 (7.38) |

| DDD of prescribed antipsychotics on the first visit in mg: mean (SD) | 1.48 (0.81) |

| The change of DDD between the two visits in mg: mean (SD) | −0.001 (0.459) |

| Participants without any changes of suicidal ideation during follow up: n (%) | 66 (64.1) |

| Participants with improvement of suicidal ideation during follow up: n (%) | 22 (21.4) |

| Participants with worsening of suicidal ideation during follow up: n (%) | 15 (14.6) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassan, A.; De Luca, V.; Dai, N.; Asmundo, A.; Di Nunno, N.; Monda, M.; Villano, I. Effectiveness of Antipsychotics in Reducing Suicidal Ideation: Possible Physiologic Mechanisms. Healthcare 2021, 9, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9040389

Hassan A, De Luca V, Dai N, Asmundo A, Di Nunno N, Monda M, Villano I. Effectiveness of Antipsychotics in Reducing Suicidal Ideation: Possible Physiologic Mechanisms. Healthcare. 2021; 9(4):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9040389

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassan, Ahmed, Vincenzo De Luca, Nasia Dai, Alessio Asmundo, Nunzio Di Nunno, Marcellino Monda, and Ines Villano. 2021. "Effectiveness of Antipsychotics in Reducing Suicidal Ideation: Possible Physiologic Mechanisms" Healthcare 9, no. 4: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9040389

APA StyleHassan, A., De Luca, V., Dai, N., Asmundo, A., Di Nunno, N., Monda, M., & Villano, I. (2021). Effectiveness of Antipsychotics in Reducing Suicidal Ideation: Possible Physiologic Mechanisms. Healthcare, 9(4), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9040389