Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Background on Care and Disability

1.2. The Impact of Taking Care of a Person with a Physical Disability

1.2.1. Gender Differentiation

1.2.2. Protective Factors and Psychological Characteristics Present in Caregivers

1.3. The Current Study

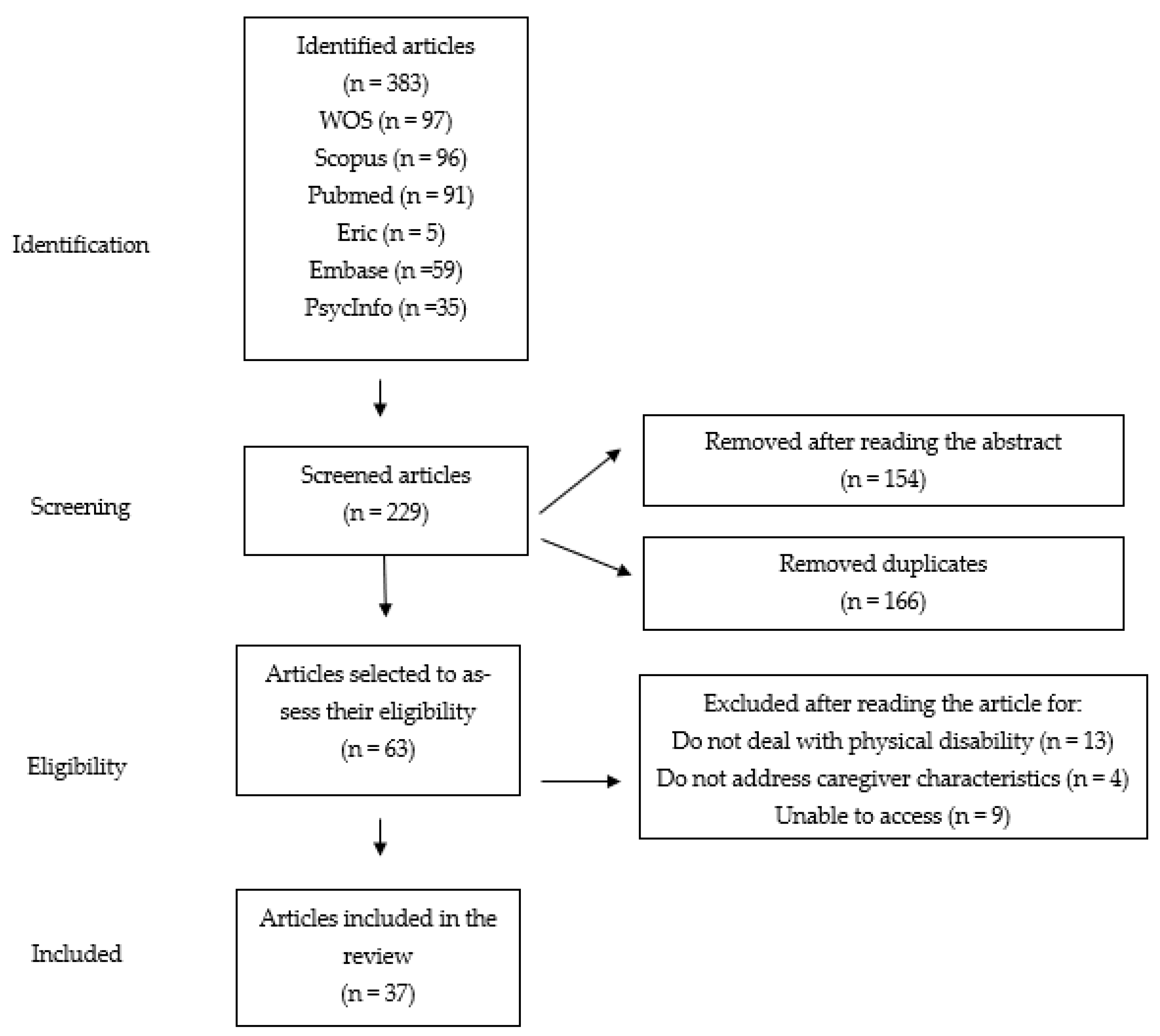

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search

2.2. Eligibility

2.3. Identification of Data Sources and Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Selection

2.6. Methodological Limitations

- (a)

- Assessing the quality of the literature: The quality of each selected study was not assessed because the systematic review conducted was essentially descriptive and not evaluative. This was due to several reasons: First, it favored a large coverage of the studies retrieved and selected synthetic descriptions of the studies. Second, the selected studies led to the observation and highlighting of possible biases in them, such as the induction of the reliability and validity of the measures used, among other things noted above. These specific limitations would have been unnoticed if a filter was introduced on these aspects. This does not indicate the absolute absence of quality assessment of the studies because some assessment of this quality was partially guaranteed by the selection of the databases (e.g., WoS and Scopus), whose selective processes are high for choosing the journals receiving research articles.

- (b)

- The term psychological characteristics* suggests a wide range of psychological attributes linked to caregivers; however, there are many other attributes that could not be included in this review and, therefore, that are part of the methodological limitations of the current work. Despite this, it is important to note that other articles such as Berenguí et al. (2013) have also been published in high-impact journals and have used this combination of terms, considering the possibility that some psychological indicators were omitted [28].

- (c)

- Most of the studies analyzed do not report the sampling strategies used (i.e., probabilistic or non-probabilistic), the type of approach of the studies (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, or mixed), or the type of design they followed (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal).

3. Results

3.1. Importance of the Physical, Social, and Cultural Context

3.2. Methodological Aspects of the Analyzed Studies

3.3. Impact and Psychological Characteristics Present in Caregivers

3.3.1. Physical Problems Associated with Caregiving

3.3.2. Psychological and Mental Problems Associated with Caring

Well-Being and Quality of Life

Emotional Stress and Psychological Distress

Anxiety and Depression

Burden Associated with Caregiving

3.3.3. Other Problems Associated with Caregiving (Social, Family, and Financial)

3.3.4. Individual and Protective Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implication

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study Number | Country | Physical Disability | Type of Sample | Instruments | Type of Caregiver | Distribution by Sex | Age | Employment Status | Variables Present in Caregivers | Biases in Sample Selection | Other Important Considerations of Caregivers | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. [36] | USA | Physical disability | Adults | Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (α = 0.816) | Informal | Women (89.1%) Men (10.9%) | 30–89 | NR | Emotional stress Physical stress | NR | Musculoskeletal discomfort (MSD) associated with care activities MSD interference with ability to provide care and participate in life activities | Some influences on the physical difficulties experienced by caregivers may not have been addressed |

| 2. [32] | USA | Physical disability | NR | BRFSS telephone survey (2009) (α = NR) | Informal | Women (27.2%) Men (22%) | 18–64/65 or over | Unemployed (24.8%) Employee (24.6%) | Physical distress Mental distress Dissatisfaction with life | NR | Older caregivers reported fair or poor self-rated health and more frequent physical distress | Lack of data on patients and amount of time spent on care |

| 3. [58] | Japan | Type 1 myotonic dystrophy | Adults | SF-36 (α = 0.7) CES-D (Depression α = 0.9 and well-being α = 0.75) ESS (α = 0.72) ZBI (α = 0.86) | Informal | Women (n = 23) Men (n = 20) | NR | NR | Anxiety Low quality of life Burden | NR | Being female is associated with higher burden of care Burden is related to patients’ depressive symptoms and symptom severity | NR |

| 4. [68] | USA | All types of disabilities, including physical disability | NR | NR | Informal | NR | Middle age | Autonomous, farmers, or unskilled workers | Depression Anxiety Despair Low quality of life | NR | Social burden Restriction on social life Reduction in financial income Problems related to physical burden (fatigue or tiredness) | Data may be biased |

| 5. [87] | Spain | Parkinson’s disease | Adults | NR | Informal | NR | NR | NR | Good caregiver–patient relationship Perceived social support and positive personality traits mitigate negative effects on caregivers’ quality of life | NR | Caregiver quality influenced by the presence of depression in patients and symptomatology | Most interventions are aimed at the caregiver and the patient, it is difficult to separate the benefits Long-term follow-up needed |

| 6. [35] | Saudi Arabia | Chronic diseases and/or disabilities (including physical) | Elderly | ZBI (α = 0.86) | Informal | Women (52.7%) Men (47.3%) | 18 or over | Unemployed (54.6%) Full-time (35.9%) Part-time (9.5%) | Moderate burden associated with care | NR | Musculoskeletal problems | The study was only carried out in Riyadh |

| 7. [62] | USA | Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Young people | Beck Depression Inventory (α = 0.83) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (α = 0.88) SF-36 (α = 0.7) Family Environment Scale (FES) (cohesion α = 0.86, conflict α = 0.85, and expressiveness α = 0.73) | Informal | NR | NR | NR | Depression Low mental health | NR | Family conflicts are related to mental, health, and quality of life deterioration of caregivers and children | There is a need to include measures that address parental strengths and more research on the relationship between family functioning and child well-being |

| 8. [44] | Spain | Musculoskeletal diseases | Adults | The speech carried out by the discussion group was transcribed and analyzed | Informal | G1 men (n = 3) and women (n = 6), G2 men (n = 4) and women (n = 5) | 31–65 | NR | Social isolation Emotional stress High emotional burden | NR | Loss of purchasing power Work-related problems The support caregivers receive modulates their emotional burden | Type of diseases not specified |

| 9. [59] | Canada | Physical disability | Elderly | SF-36 (α = 0.7) | Informal | Most were women | Spouses (AA = 74.8), not relatives (AA = 62.7), sons, and daughters (AA = 49.7) | NR | Worse mental health status when patients had depression Women are at higher risk for poor mental health | NR | Female caregivers had worse physical function than male caregivers | Small sample size Measurement of depression underestimated previous depressive episodes |

| 10. [22] | USA | Traumatic spinal cord injury | All ages | Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (α = 0.94). ADLs (α = 0.86, 0.81, 0.90, and 0.91) Caregiver burden (α = 0.69, 0.71, 0.83, and 0.80) Family conflict (α = 0.83, 0.86, 0.91, and 0.91) Relative Stress Scale (RSS) (α = 0.89, 0.90, 0.92, and 0.93) Loss of self (α = 0.92, 0.88, 0.89, and 0.87) Distress perceived by the person with the spinal cord injury (α = 0.85, 0.85, 0.88, and 0.87) Personal benefit (α = 0.72, 0.69, 0.75, and 0.80) Competence (α = 0.68, 0.70, 0.68, and 0.70) Expressive support (α = 0.70, 0.78, 0.77, and 0.80) Support scale that assesses social integration (α = 0.56, 0.70, 0.70, and 0.76) PANAS Positive affects (α = 0.86, 0.88, 0.90, and 0.89) Negative affects (α = 0.89, 0.91, 0.85, and 0.90) CESD (α = 0.90, 0.88, 0.92, and 0.93) STAI (α = 0.94, 0.93, 0.94, and 0.95) PILL (α = 0.93, 0.94, 0.92, and 0.95.) | Informal | 20 men (15.6%) 108 women (84.4%) | AA = 40.8 | Unemployed (49.2%) Full-time (34.4%) Part-time (8.6%) | The greater the resilience, the less anxiety, health problems, and negative affect The longer the care period, the greater the anxiety, negative affect, and poorer health | NR | The resilient group had greater social support Chronic caregivers showed more family conflicts and greater difficulties in showing support | Certain characteristics such as ethnicity or income of caregivers were not taken into account |

| 11. [70] | Sweden | Physical disability | Adults | Joint and semi-structured interviews with couples | Informal | NR | 60–83 | NR | Caregiving perceived as freedom generates a higher degree of satisfaction with care and with one’s own life Caregiving perceived as an obligation generates ambivalent feelings that attenuate their well-being | Losses | When caregiving is perceived as freedom, mutual help and formal support were positively valued Caregiving perceived as an obligation was seen as a moral imperative to care for the partner | It was limited to couples with physical disabilities Due to the wide range of physical disabilities, couples require different types of assistance at different times |

| 12. [9] | Netherlands | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | Young people | Caregiver Stress Index (CSI) (α = 0.86) Self-Rated Burden scale (SRB) (α = NR) CarerQoL (α = NR) EuroQoL (α = NR) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (α = 0.85) Utrecht Coping List (UCL) (α = NR) | Informal | NR | AA = 57 | NR | Reduced well-being due to lack of free time and continuous care Depression and anxiety no more prevalent than in the general population | Losses | Parents who care for their children experience substantial burden, but they value care in a positive and rewarding way | Selection bias Since it is a cross-sectional design, causal relationships cannot be detected |

| 13. [38] | Saudi Arabia | Physical disability | Adults | GHQ-28 (α = 0.91) | Formal | Most were women | AA = 33.46 ± 5.29 | Healthcare workers | Prevalence of somatic disorder 2%, anxiety disorder 3%, depression 1%, stress 8% | NR | Female caregivers had a higher prevalence of depression | Very small sample size Low participation of patients with disabilities |

| 14. [53] | India | Physical disability | Elderly | ZBI (α = 0.91) Barthel Index ADL (α = 0.86–0.92) HMSE (α = NR) Whisper test (α = NR) Roman’s vision test (α = NR) | Informal | Women (90%) Men (10%) | AA = 45.4 ± 15.7 | Unemployed (12.1%) Employee (15%) Housekeeper (54.3%) Other (18.6%) | The presence of disability in the person receiving care is related to a greater burden on the main caregiver | NR | People with physical disabilities and sensory problems generate a greater burden on caregivers | Small sample size Coping strategies and support perceived by the caregiver were not measured |

| 15. [54] | Switzerland | Spinal cord injury | Young people | ZBI-S (α = 0.88) ADL (α = 0.84) IADL (α = 0.72) Quality of Relationships Inventory (α = 0.84) | Informal | Women (72.9%) Men (27.1%) | AA = 50 | NR | Quality of intimate relationships reduces stress and burden Higher subjective caregiver burden in couples with low reciprocity | Insignificant | Caregivers who receive support from professionals have greater feelings of satisfaction with care | Small sample size Emotional support was not studied |

| 16. [56] | Spain | Multiple sclerosis | Adults | Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) (α = NR) Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (α = NR) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (α = NR) Clock Drawing Test (CDT) (α = NR) Hamilton Depresion Rating Scale (HDRS) (α = between 0.76 and 0.92) ZBI (α = 0.91) | Informal | NR | NR | NR | Emotional burden related to the physical disability of people receiving care | NR | Influence on occupational status Most caregivers do not accept the disease and perceive a lack of support from family members | NR |

| 17. [88] | Israel | Physical disability | All ages | CES-D (α = 0.85) | Informal | Women (100%) | 45–64 | Most were employed | Caregivers of a child or spouse suffer greater burden and a higher level of depressive mood compared to those who care for their parents | NR | Caregivers who are in charge of a child or spouse perceive worse health than those who take care of their parents Caregivers who are in charge of a child or spouse reported needing psychological counseling | Measures such as coping strategies were not studied Small sample size |

| 18. [43] | USA | Physical and mental disability | Elderly | Subjective perception of self-reported health (α = NR) Work satisfaction (α = NR) Survey Work-Home Interaction-Nijmegen (SWING) (α = between 0.77 and 0.89) Ryff Psychological Well-being Scale (self-acceptance α = 0.83 and personal growth α = 0.68) | Informal | Women (65.4%) Men (34.6%) | AA = 53.12 | NR | High levels of tension and low levels of well-being Low levels of psychological health (depression, anxiety, stress, etc.) | NR | Caregivers who provided long-term care showed greater conflict between family and work | The sample was collected in 1992, so the population and the characteristics of the caregivers have changed |

| 19. [31] | USA | Functional diversity | Adults | ADLs (α = NR) IADLs (α = NR) | Informal | Women (n = 218) Men (n = 148) | 65 and over | NR | Wives reported lower care-related quality of life Level of primary care-related stressors affects men and women equally | NR | Older caregivers and those who perceived greater burden reported a reduction in certain tasks that they rated positively Husbands tended to show poorer quality of care when their partner showed a higher number of chronic conditions Greater family disagreements when caregivers perceived greater burden | Since it is a cross-sectional design, causal relationships cannot be detected |

| 20. [55] | Malaysia | Physical disability | Young people | Caregiver Needs Screen (CNS) (α = between 0.81 and 0.90) Skills Index (α = 0.87) | Informal | NR | NR | NR | Caregivers whose children had a low functional capacity showed a higher burden Families who had a previous experience with a disabled child had gone through an adaptive care process | NR | The younger the children, the more needs expressed by caregivers Those families with a lower educational level had lower income levels and therefore required more financial support | Cultural factors may have affected responses |

| 21. [60] | Turkey | Orthopedic disability | Adults | Spinal Cord Independence Measure III (SCIM III) (α = 0.93) Social support scale (α = 0.91) Family Assessment Device (FAD) (α = 0.93) Locus of control scale (α = 0.83) Self-control scale (SCS) (α = 0.83) Adaptation to Disability Scale-Revised (ADSR) (α = 0.93) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (α = 0.91) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (α = 0.87) Index of Perceived Social Support (IoPSS) (α = 0.85) Burden Assessment Scale (BAS) (α = 0.88) Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) (α = 0.85) | Informal | Women 114 (70.81%) Men 44 (27.33%) | AA = 44.07 | Unemployed 114 (70.81%) Part-time 33 (20.50%) Full-time 10 (6.21%) | Caregivers with support networks had fewer depressive symptoms Caregiver burden was related to the presence of depressive symptoms When caregivers are kind, cared for people have fewer depressive feelings | NR | A hostile attitude or lack of warmth in the caregiver–patient interaction generated negatively charged family environments | Since it is a cross-sectional design, causal relationships cannot be detected |

| 22. [39] | Australia | Physical disability | All ages | Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (α = NR) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10) (α = NR) | Informal | Women (85%) Men (15%) | 21–86 | NR | Self-reported mental and physical health below Australian population Very high rates of depressive symptoms and psychological distress | NR | Men had better self-reported health than women Working caregivers had better self-reported health and physical functioning | Certain factors were not taken into account, such as the length of time the caregiver provides care or the stage of the disease in which the cared for person is in The number of male respondents was limited |

| 23. [42] | Norway | Severe physical disability | Adults | Subjective well-being (SWB) (α = 0.81) Symptom Checklist 10 (SCL-10) (α = 0.85) | Informal | NR | 20 and over | NR | High psychological distress Low subjective well-being Patient depression may predict caregiver depression | NR | Women are more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms. However, Norway is considered one of the most gender-equal countries in the world. | There is no information on the duration of the partners and whether the partner is the main caregiver There is no information on the duration and severity of the disease |

| 24. [89] | Italy | Multiple sclerosis | Adults | CMDI (α = NR) Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (α = between 0.77 and 0.93) | Informal | NR | NR | Full-time (47%) Part-time (10%) Housekeeper (5%) Unemployed (5%) Retired (33%) | Low mental health A greater severity of the disease is related to a poorer mood | NR | People with this disease have worse mental health scores and depressive symptoms | The survey was carried out by mail, the response rate of the control groups was very low |

| 25. [51] | USA | Multiple sclerosis | Adults | Short Form Health Survey (SF-8) (α = NR) | Informal | Men (100%) | AA = 60.7 | NR | Caregiver burden related to the number of hours of care Low support related to high levels of stress and burden | NR | Caregiving has a great impact on the performance of certain tasks of daily life | Self-selection bias |

| 26. [41] | UK | Multiple sclerosis | Adults | NR | Informal | NR | NR | NR | Low quality of life associated with factors such as duration and frequency of care Women had greater social support than men, which positively affected their life satisfaction | NR | Deficits in the physical health of caregivers Negative impact on caregiver’s social life Economic situation is negatively affected | Small sample size Recruitment in small geographic areas Limited use of assessment instruments |

| 27. [49] | USA | Physical disability | Young people | NR | Informal | Most were women | NR | Unemployed (n = 45) Sporadic work (n = 6) Part-time (n = 34) Full-time (n = 55) | Elderly caregivers are very likely to suffer from stress and symptoms of depression | NR | In this study, a white matter pathology was observed as a result of the stress associated with care | Difficulty in generalizing results to younger caregivers |

| 28. [64] | UK | Spinal cord injury | Adults | Inventory to Diagnose Depression (IDD) (α = NR) Acceptance of Disability Scale (AD) (α = NR) Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R) (α = NR) | Informal | Women (n = 55) Men (n = 11) | Women AA = 41.8 Men AA = 42.9 | Unemployed 49.2% Full-time 41.6% Part-time 9.2% | An impulsive problem-solving tendency negatively affects the family nucleus and acceptance of the disease | NR | Caregivers’ personal and leisure time is sacrificed due to caring | Small sample size |

| 29. [52] | Spain | Multiple sclerosis | All ages | Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (α = NR) Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (α = NR) | Informal | Women 56.8% Men 43.2% | AA = 50.1 +/− 12.6 | Employee 144 (51.8%) Housekeeper 87 (31.3%) Retired 32 (11.5%) Student 4 (1.4%) Unemployed 3 (1.1%) Other 5 (1.8%) Unknown 3 (1.1%) | The main predictors of caregiver burden were emotional factors and the person’s degree of disability Social and psychological support as protective factors | NR | Most of the caregivers were women due to cultural characteristics The use of formal support services is very low compared to other countries | The data were collected at a particular point in time, so it is not known whether the factors that explain the variance would be maintained over time |

| 30. [37] | Australia | Rett syndrome | Young people | SF-12 (physical dimension α = 0.63 and mental dimension α = 0.72) | Informal | Women 100% | 21–60 | Full-time 63 (47.4%) Full-time housekeeper 35 (26.3%) Does not work because of the child’s illness 32 (24.1%) Does not work for other reasons 3 (2.3%) | Perceived social support mediated the relationship between children’s functional status and depressive symptoms Mothers of children who had not had any disease-related incident showed better mental health A well-functioning family was related to better mental health of the mother | NR | Mothers taking care of a child with a disability show more adverse physical and mental health outcomes Better physical health if their children had less symptoms associated with the disease | Mothers’ mental and physical health was unknown prior to the birth of their child |

| 31. [10] | USA | Chronic physical illnesses | Adults | Caregiver Quality of Life Index (α = NR) Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (α = NR) | Informal | NR | 21 and over | NR | Women more likely to be depressed Physical disability, health problems of the cared for person, and anxiety associated with care were considered aspects that reduced the caregiver’s quality of life Appropriate coping strategies lead to a better quality of life | NR | Primary stressors: the deterioration of the patient, the dependence that the patient required in the activities of daily living, the recurrence of the disease, or the problematic behaviors that the caregiver might present. These factors were related to a reduction in the caregiver’s quality of life. | NR |

| 32. [46] | Asia | Physical and mental disability | Elderly | In-depth interviews | Formal and informal | Women 59 Men 27 | 20–72 | NR | Failure to ask others for help affected health and well-being | NR | The main support of the caregivers was the family members themselves Most of the caregivers were women and hardly asked for help from formal support | NR |

| 33. [90] | USA | Chronic diseases, including physical disability | Adults | NR | Informal | NR | NR | NR | Physical and psychological health consequences for caregivers Stress | NR | High objective burden associated with care Caregiving affects the social, family, personal, and economic spheres | NR |

| 34. [69] | Netherlands | Rheumatic diseases | NR | Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview (α = 0.88) | Informal | Women (72%) Men (28%) | AA = 52 | NR | Severe burden related to the care of people suffering from rheumatic diseases | NR | Social support as a protective factor against the disease and the work carried out by caregivers | NR |

| 35. [30] | USA | Multiple sclerosis | Adults | Mobility subscale (α = NR) Perceived social support (α = 0.70) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (α = 0.81) | Informal | Women 38 (90.5%) Men 4 (9.5%) | AA = 51.6 | NR | Depressive symptoms in minor caregivers when they perceived social support Caregivers who had a poor support network showed poorer psychological well-being | NR | The greater the severity of the disease, the worse the well-being of caregivers | The type and quality of perceived social support were not objectively assessed |

| 36. [63] | USA | Spinal cord injury | All ages | Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised (SPSI-R) (α = between 0.72 and.85) Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (α = between 0.62 and 0.96) Inventory to Diagnose Depression (IDD) (α = 0.92) | Informal | Women (n = 103) Men (n = 18) | AA = 46 | NR | The more severe the injury, the greater the emotional distress | NR | Poor problem-solving skills, predictors of poorer psychological adjustment of caregivers | Since it is a cross-sectional design, causal relationships cannot be detected Small sample of men |

| 37. [91] | Switzerland | Spinal cord injury | Adults | Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) (α = NR) Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (α = 0.87) Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (α = between 0.86 and 0.90) Positive affect (α = between 0.84 and 0.87) Negative affect MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (α = NR) | Informal | Most were women | NR | Employee (n = 88) | High care control related to improved caregiver well-being and reduced negative affectivity | NR | Caregivers showed greater positive affect when they observed that people with the injury had good work control Poor socioeconomic conditions were related to low control at work and care | Small sample size Data obtained from self-report may be biased by intrinsic personality characteristics |

References

- Martín, M.; Ripollé, M. La discapacidad dentro del enfoque de capacidades y funcionamientos de Amartya Sen. Rev. Educ. 2008, 10, 64–94. [Google Scholar]

- García, E. Puesta al día: Cuidador informal. Rev. Enfermería Castilla Y León. 2016, 8, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, A.; Romañach, J. El Modelo de la Diversidad: La Bioética y los Derechos Humanos Como Herramientas Para Alcanzar la Plena Dignidad en la Diversidad Functional; Diversitas: Valencia, España, 2006; ISBN 84-964-7440-2. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Discapacidades. Available online: https://www.who.int/topics/disabilities/es/ (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Tijero, M.C. El Origen de la Mujer Cuidadora: Apuntes Para el Análisis Hermenéutico de los Primeros Testimonios. Index De Enfermería. 2016, 25, 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan, J. Stress Overload: A New Approach to the Assessment of Stress. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2011, 49, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindt, N.; van Berkel, J.; Mulder, B. Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics. 2020, 20, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandín, B. El estrés: Un análisis basado en el papel de los factores sociales. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2003, 3, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Pangalila, R.; van den Bos, G.; Stam, H.; van Exel, N.; Brouwer, W.; Roebroeck, M. Subjective caregiver burden of parents of adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 34, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.; Zebrack, B. Caring for family members with chronic physical illness: A critical review of caregiver literature. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Martínez, Á.; Hidalgo-Moreno, G.; Moya-Albiol, L. Neuropsychological consequences of chronic stress: The case of informal caregivers. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 24, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgis, A.; Lambert, S.; Johnson, C.; Waller, A.; Currow, D. Physical, Psychosocial, Relationship, and Economic Burden of Caring for People with Cancer: A Review. J. Oncol. Pract. 2013, 9, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grad, J.; Sainsbury, P. Mental illness and the family. Lancet 1963, 281, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Á.; Córdoba, A.; Poches, D. Escala de sobrecarga del cuidador Zarit: Estructura factorial en cuidadores informales de Bucaramanga. Rev. De Psicol. 2016, 8, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, V.; Roche, R.; Escotorin, P. Cuidar con Actitud Prosocial. Nuevas Propuestas Para Cuidadores; Ciudad Nueva: Madrid, España, 2017; p. 185. ISBN 978-84-9715-385-0. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, R.; Sherwood, P.R. Physical and Mental Health Effects of Family Caregiving. Am. J. Nurs. 2008, 108, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calasanti, T. Gender Relations and Applied Research on Aging. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinquart, M.; Sorensen, S. Gender Differences in Caregiver Stressors, Social Resources, and Health: An Updated Meta-Analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, J.; Heyne, M.M.; Lam, C.S. Acceptance of Disability among Chinese Inspaniduals with Spinal Cord Injuries: The Effects of Social Support and Depression. Psychology 2012, 03, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, T.; Marmot, M.; Siegrist, J. Failed reciprocity in close social relationships and health: Findings from the Whitehall II study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño-Moreno, S.; Chaparro-Díaz, L. Calidad de vida de los cuidadores de personas con enfermedad crónica. Aquichan 2016, 16, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, T.R.; Berry, J.W.; Richards, J.S.; Shewchuk, R.M. Resilience in the initial year of caregiving for a family member with a traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 1072–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelato, G. Resiliencia en el maltrato infantil: Aportes para la comprensión de factores desde un modelo ecológico. Rev. De Psicol. 2011, 29, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, P.; Phipps, S. Economic costs of caring for children with disabilities in Canada. Can. Public Polic. 2009, 35, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exton-Smith, A.N. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in the elderly. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1984, 43, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora, L. Enfoques y Diseños de Investigación Social: Cuantitativos, Cualitativos y Mixtos, 1st ed.; Euned: Madrid, España, 2017; p. 524. ISBN 978-9968-48-366-7. [Google Scholar]

- Berengüí-Gil, R.; de Los Fayos, E.; Hidalgo-Montesinos, M. Características Psicológicas Asociadas a la Incidencia de Lesiones en Deportistas de Modalidades Individuales. Ann. Psychol. 2013, 29, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Epner, D.; Baile, W. Patient-centered care: The key to cultural competence. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bambara, J.K.; Turner, A.P.; Williams, R.M.; Haselkorn, J.K. Social support and depressive symptoms among caregivers of veterans with multiple sclerosis. Rehabil. Psychol. 2014, 59, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polenick, C.; DePasquale, N. Predictors of Secondary Role Strains Among Spousal Caregivers of Older Adults with Functional Disability. Gerontologist 2018, 59, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.A.; Edwards, V.J.; Pearson, W.S.; Talley, R.C.; McGuire, L.C.; Andresen, E.M. Adult caregivers in the United States: Characteristics and differences in well-being, by caregiver age and caregiving status. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, E135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abellán, A.; Ayala, A.; Pérez, J. Los Nuevos Cuidadores. Available online: https://observatoriosociallacaixa.org/-/los-nuevos-cuidadores (accessed on 24 April 2021).

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of Feelings of Burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.; Alzahrani, A.; Alabduljabbar, K.; Aldaghri, A.; Alhusainy, Y.; Khan, M.; Alshuwaier, R.; Kariz, I. The burden perceived by informal caregivers of the elderly in Saudi Arabia. J. Fam. Community Med. 2017, 24, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, A.R.; Sommerich, C.M.; Lavender, S.A.; Tanner, K.J.; Vogel, K.; Campo, M. Musculoskeletal Discomfort, Physical Demand, and Caregiving Activities in Informal Caregivers. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2013, 34, 734–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurvick, C.L.; Msall, M.E.; Silburn, S.; Bower, C.; Klerk, N.; Leonard, H. Physical and Mental Health of Mothers Caring for a Child with Rett Syndrome. Pediatrics 2006, 118, 1152–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, M.; Alfahaid, F.; Almansour, M.; Alghamdi, T.; Ansari, T.; Sami, W.; Otaibi, T.; Humayn, A.; Enezi, M. Prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in health-care givers of disabled patients in Majmaah and Shaqra cities, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, R.; Wark, S.; Dillon, G.; Ryan, P. Self-reported physical and mental health of Australian carers: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuorinka, I.; Jonsson, B.; Kilbom, A.; Vinterberg, H.; Biering-Sorensen, F.; Andersson, G.; Jorgensen, K. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl. Ergon. 1987, 18, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeown, L.P.; Porter-Armstrong, A.P.; Baxter, G.D. The needs and experiences of caregivers of individuals with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Clin. Rehabil. 2003, 17, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borren, I.; Tambs, K.; Idstad, M.; Ask, H.; Sundet, J.M. Psychological distress and subjective well-being in partners of somatically ill or physically disabled: The Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Scand. J. Psychol. 2012, 53, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramble, R.J.; Duerk, E.K.; Baltes, B.B. Finding the Nuance in Eldercare Measurement: Latent Profiles of Eldercare Characteristics. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 35, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, N.; Lázaro, P.; Gabriele, G.; Garcia-Vicuña, R.; Jover, J.A.; Sevilla, J. Perceptions, attitudes and experiences of family caregivers of patients with musculoskeletal diseases: A qualitative approach. Reumatol Clin. 2013, 9, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N.; Baldwin, L.; Bishop, D. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J. Marital. Fam. Ther. 1983, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katbamna, S.; Ahmad, W.; Bhakta, P.; Baker, R.; Parker, G. Do they look after their own? Informal support for South Asian carers. Health Soc. Care Community 2004, 12, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, N.; Jenaro, C.; Moro, L.; Tomşa, R. Salud y calidad de vida de cuidadores familiares y profesionales de personas mayores dependientes: Estudio comparativo. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2015, 4, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, I.F.; Fee, H.R.; Wu, H.S. Negative and positive caregiving experiences: A closer look at the intersection of gender and relatioships. Fam. Relat. 2012, 61, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resch, J.; Benz, M.; Elliott, T. Evaluating a dynamic process model of wellbeing for parents of children with disabilities: A multi-method analysis. Rehabil. Psychol. 2012, 57, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez, J.; Ruíz, M.; Gómez, I.; Gallego, E.; Valero, J.; Izquierdo, M. Ansiedad y depresión en cuidadores de pacientes dependientes. Semergen 2012, 38, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, R.; Radin, D.; Huang, C. Burden among male caregivers assisting people with multiple sclerosis. Gend. Med. 2010, 7, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Navarro, J.; Benito-León, J.; Oreja-Guevara, C.; Pardo, J.; Bowakim Dib, W.; Orts, E.; Belló, M. Burden and health-related quality of life of Spanish caregivers of persons with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2009, 15, 1347–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay, S.; Kasthuri, A.; Kiran, P.; Malhotra, R. Association of impairments of older persons with caregiver burden among family caregivers: Findings from rural South India. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 68, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tough, H.; Brinkhof, M.W.; Siegrist, J.; Fekete, C. Subjective Caregiver Burden and Caregiver Satisfaction: The Role of Partner Relationship Quality and Reciprocity. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2042–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H. Assessing the needs of caregivers of children with disabilities in Penang, Malaysia. Health Soc. Care Community 2017, 25, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Gonzáles, J.; Benito-León, J.; Rivera-Navarro, J.; Mitchell, A.; GEDMA Study Group. A systematic approach to analyse health-related quality of life in multiple sclerosis: The GEDMA study. Mult. Scler. 2004, 10, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Gryskiewicz, N.D. The Creative Environment Scales: Work Environment Inventory. Creat. Res. J. 1989, 2, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurauchi, G.; Endo, M.; Odaira, K.; Ono, R.; Koseki, A.; Goto, M.; Sato, Y.; Kon, S.; Watanabe, N.; Sugawara, N.; et al. Caregiver Burden and Related Factors Among Caregivers of Patients with Myotonic Dystrophy Type 1. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2019, 6, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, J.; Latimer, E.; Cole, M.; Ciampi, A.; Sewitch, M. Major depression among medically ill elders contributes to sustained poor mental health in their informal caregivers. Age Ageing 2007, 36, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Secinti, E.; Selcuk, B.; Harma, M. Personal and familial predictors of depressive feelings in people with orthopedic disability. Health Psychol. Rep. 2017, 5, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Horton, T.; Wallander, J. Hope and social support as resilience factors against psychological distress of mothers who care for children with chronic physical conditions. Rehabil. Psychol. 2001, 46, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knafl, K.; Leeman, J.; Havill, N.; Crandell, J.; Sandelowski, M. The Contribution of Parent and Family Variables to the Well-Being of Youth with Arthritis. J. Fam. Nurs. 2015, 21, 579–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreer, L.; Elliott, T.; Shewchuk, R.; Berry, J.; Rivera, P. Family caregivers of persons with spinal cord injury: Predicting caregivers at risk for probable depression. Rehabil. Psychol. 2007, 52, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, T.; Shewchuk, R.; Richards, J. Caregiver social problem-solving abilities and family member adjustment to recent-onset physical disability. Rehabil. Psychol. 1999, 44, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Zurilla, T.; Maydeu-Olivares, A. Conceptual and methodological issues in social problem-solving assessment. Behav. Ther. 1995, 26, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrush, A.; Hyder, A. The neglected burden of caregiving in low- and middle-income countries. Disabil. Health J. 2014, 7, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buitrago-Garcia, D.; Villarreal, L.; Cabrera, M.; Santos-Moreno, P.; Rodriguez, F. AB1395-HPR Burden in caregivers of patients with rheumatic conditions. An. De Las Enferm. Reumáticas 2018, 77, 1857–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgé, C. Freedom and Imperative. J. Fam. Nurs. 2014, 20, 204–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, G.; Sarason, I.; Sarason, B. General and relationship-based perceptions of social support: Are two constructs better than one? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, G.; Dahlem, N.; Zimet, S.; Farley, G. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, J.; de la Vega, R.; Gertz, K.J.; Jensen, M.P.; Engel, J.M. The role of perceived family social support and parental solicitous responses in adjustment to bothersome pain in young people with physical disabilities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, V.; Guisande, M.; Sánchez, M.; Otero, P.; López, L.; Vázquez, F. Síndrome de carga del cuidador y factores asociados en cuidadores familiares gallegos. Rev. Española Geriatría Y Gerontol. 2019, 54, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.; Hayashi, Y.; Firth, L.; Stokes, M.; Chambers, S.; Cummins, R. Volunteering and Well-Being: Do Self-Esteem, Optimism, and Perceived Control Mediate the Relationship? J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2008, 34, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, A. The effects of chronic stress on health: New insights into the molecular mechanisms of brain–body communication. Future Sci. OA 2015, 1, FSO23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, K.J.; Philp, I.; Lamura, G.; Prouskas, C.; Öberg, B.; Krevers, B.; Spazzafumo, L.; Bién, B.; Parker, C.; Nolan, M.R.; et al. The COPE index a first stage assessment of negative impact, positive value and quality of support of caregiving in informal carers of older people. Aging Ment. Health 2003, 7, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpi, A.; Zurriaga, R.; González, P.; Marzo, J.; Buunk, A. Autoeficacia y percepción de control en la prevención de la enfermedad cardiovascular. Univ. Psychol. 2010, 9, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, H. Roles of perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy to volunteer tourists’ intended participation via theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 20, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, J.; Ras, E.; Hospital, I.; Vila, A. Profile of the main caregiver and assessment of the level of anxiety and depression. Aten Primaria 2003, 31, 338–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useros, M.; Rozalén, A.; Martínez, C.; Espín, A.; Alcaraz, F.; Martínez, A. Autoestima, apoyo familiar y social en cuidadores familiares de personas dependientes. Metas De Enfermería 2010, 13, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, V.; Calvo, B.; Martín, L.; Campos, F.; Castillo, I. Resiliencia y el modelo Burnout-Engagement en cuidadores formales de ancianos. Psicothema 2016, 18, 791–796. [Google Scholar]

- Vacha-Haase, T.; Kogan, L.R.; Thompson, B. Sample compositions and variabilities in published studies versus those in test manuals: Validity of score reliability inductions. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2000, 60, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Soto, C.A.; Calderón-De la Cruz, G.A. Validity of Peruvian studies on stress and burnout. Rev. Peru. De Med. Exp. Y Salud Publica 2018, 35, 353–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merino-Soto, C.; Angulo-Ramos, M. Validity induction: Comments on the study of Compliance Questionnaire for Rheumatology. Rev. Colomb. Reumatol. 2021, 28, 312–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino-Soto, C.; Angulo-Ramos, M. Metric studies of the compliance questionnaire on rheumatology (CQR): A case of validity induction? Reumatol. Clínica 2021, S1699–258X, 00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, P.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Forjaz, M.J. Quality of life and burden in caregivers for patients with Parkinson’s disease: Concepts, assessment and related factors. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2012, 12, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, R.; Brammli-Greenberg, S.; Bentur, N. Women Caring for Disabled Parents and Other Relatives. Soc. Work. Health Care 2003, 37, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.; Ferrari, G.; Radice, D.; Randi, G.; Bisanti, L.; Solari, A. Health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms in significant others of people with multiple sclerosis: A community study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012, 19, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sales, E. Family burden and quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 13, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, C.; Tough, H.; Brinkhof, M.W.G.; Siegrist, J. Does well-being suffer when control in productive activities is low? A dyadic longitudinal analysis in the disability setting. J. Psychosom. Res. 2019, 122, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Main Characteristics | n | % | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of caregivers | |||

| Formal caregivers | 2 | 5.40% | 13, 32. |

| Informal caregivers | 35 | 94.60% | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37. |

| Sample type (people receiving care) | |||

| Young people | 6 | 16.22% | 7, 12, 15, 20, 27, 30. |

| Adults | 18 | 48.65% | 1, 3, 5, 8, 11, 13, 16, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 31, 33, 35, 37. |

| Elderly | 5 | 13.51% | 6, 9, 14, 18, 32. |

| All ages | 5 | 13.51% | 10, 17, 22, 29, 36. |

| NR | 3 | 8.11% | 2, 4, 34. |

| Distribution by sex (caregivers) | |||

| Men | 1 | 2.70% | 25 |

| Women | 5 | 13.51% | 9, 17, 27, 30, 37. |

| Both | 19 | 51.35% | 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 21, 22, 28, 29, 32, 34, 35, 36. |

| NR | 12 | 32.43% | 4, 5, 7, 11, 12, 16, 20, 23, 24, 26, 31, 33. |

| Type of design | |||

| Cross-sectional | 21 | 56.76% | 5, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 27, 29, 34, 35, 36. |

| Longitudinal | 8 | 21.62% | 3, 9, 10, 16, 24, 28, 30, 17. |

| NR | 8 | 21.62% | 1, 2, 4, 7, 26, 31, 32, 33 |

| Sampling strategies | |||

| Probabilistic | 6 | 16.21% | 6 (SS), 9 (SRS), 24 (SRS), 19 (SS), 20 (SS), 22 (SS) |

| Non-probabilistic | 9 | 24.32% | 1 (CS), 2 (QS), 3 (QS), 8 (QS), 11 (SBS), 12 (SBS), 13 (CS), 15 (QS), 16 (QS) |

| NR | 22 | 59.46% | 4, 5, 7, 10, 14, 17, 18, 21, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 |

| Type of approach | |||

| Quantitative | 5 | 13.51% | 3, 6, 21, 27, 29 |

| Qualitative | 4 | 10.81% | 8, 11, 32, 35 |

| Mixed | 4 | 10.81% | 1, 7, 16, 37 |

| NR | 24 | 64.86% | 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 30.31, 33, 34, 36 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cejalvo, E.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Aguirre-Morales, M.T. Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121690

Cejalvo E, Martí-Vilar M, Merino-Soto C, Aguirre-Morales MT. Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2021; 9(12):1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121690

Chicago/Turabian StyleCejalvo, Elena, Manuel Martí-Vilar, César Merino-Soto, and Marivel Teresa Aguirre-Morales. 2021. "Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 9, no. 12: 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121690

APA StyleCejalvo, E., Martí-Vilar, M., Merino-Soto, C., & Aguirre-Morales, M. T. (2021). Caregiving Role and Psychosocial and Individual Factors: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 9(12), 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121690