Winners and Losers in Palliative Care Service Delivery: Time for a Public Health Approach to Palliative and End of Life Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Objectives

3. Methodology

- Priority 1. Care is accessible to everyone, everywhere

- Priority 2. Care is person-centred

- Priority 3. Care is coordinated

- Priority 4. Families and carers are supported

- Priority 5. All staff are prepared to care

- Priority 6. The community is aware and able to care

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Survey Respondents

4.2. Non-Users’ Reasons for Not Receiving Palliative Care

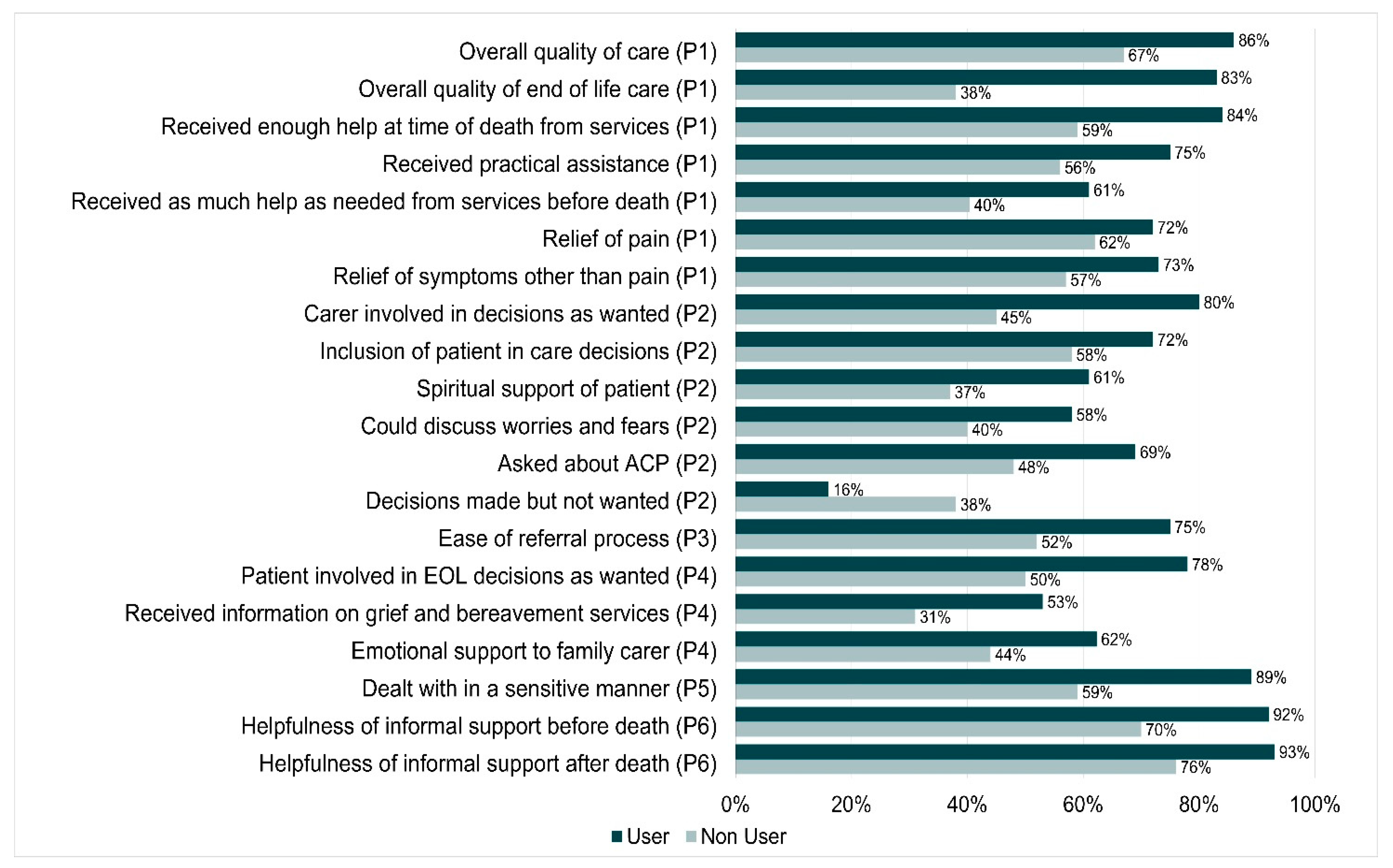

4.3. Differences in Quality Indicators within the Six Priorities

4.4. Differences in Care between Users and Non-Users of Palliative Care Services

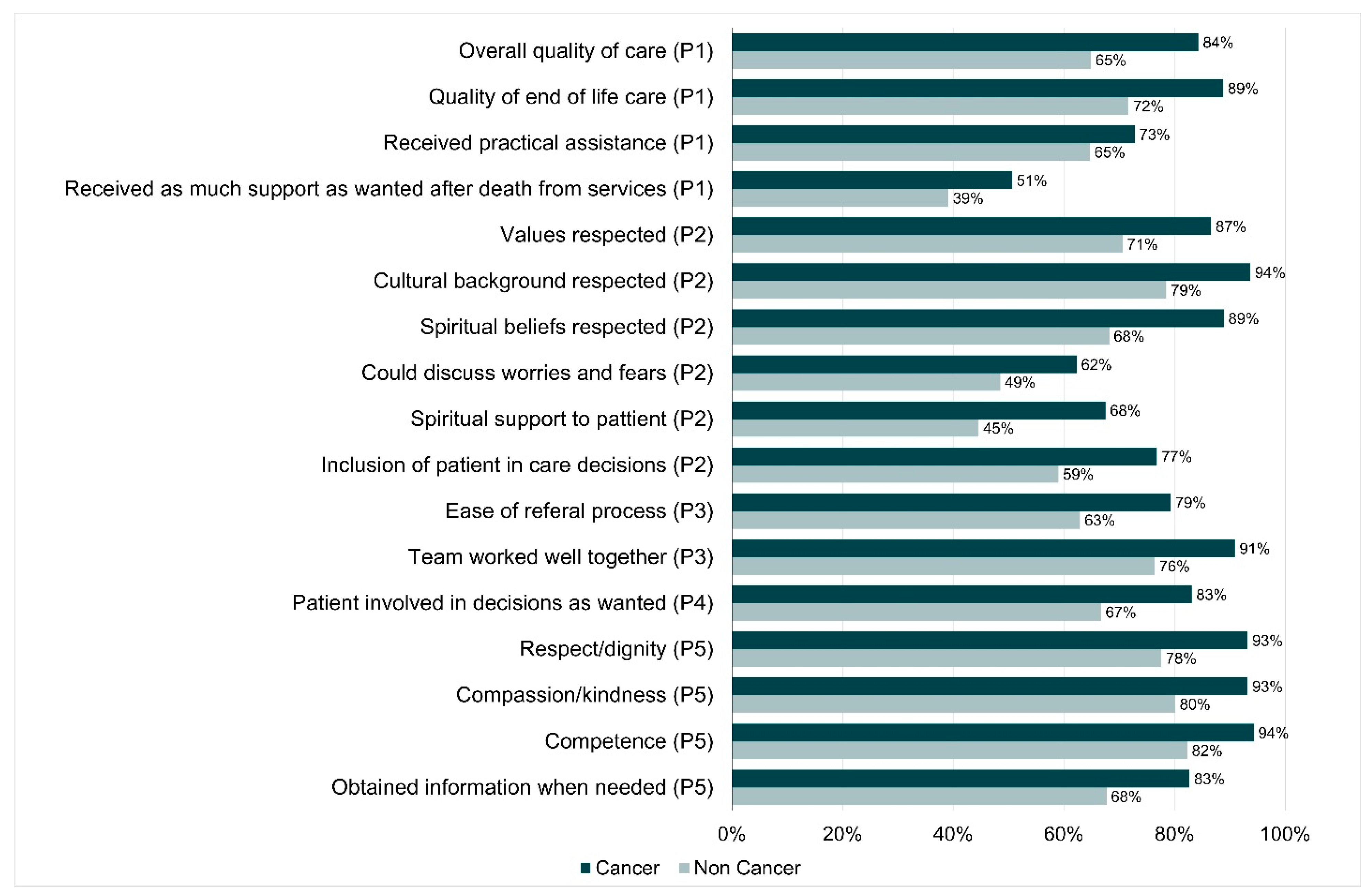

4.5. Differences in Care between Cancer and Non-Cancer Conditions

4.6. What Could Have Worked Better for Consumers?

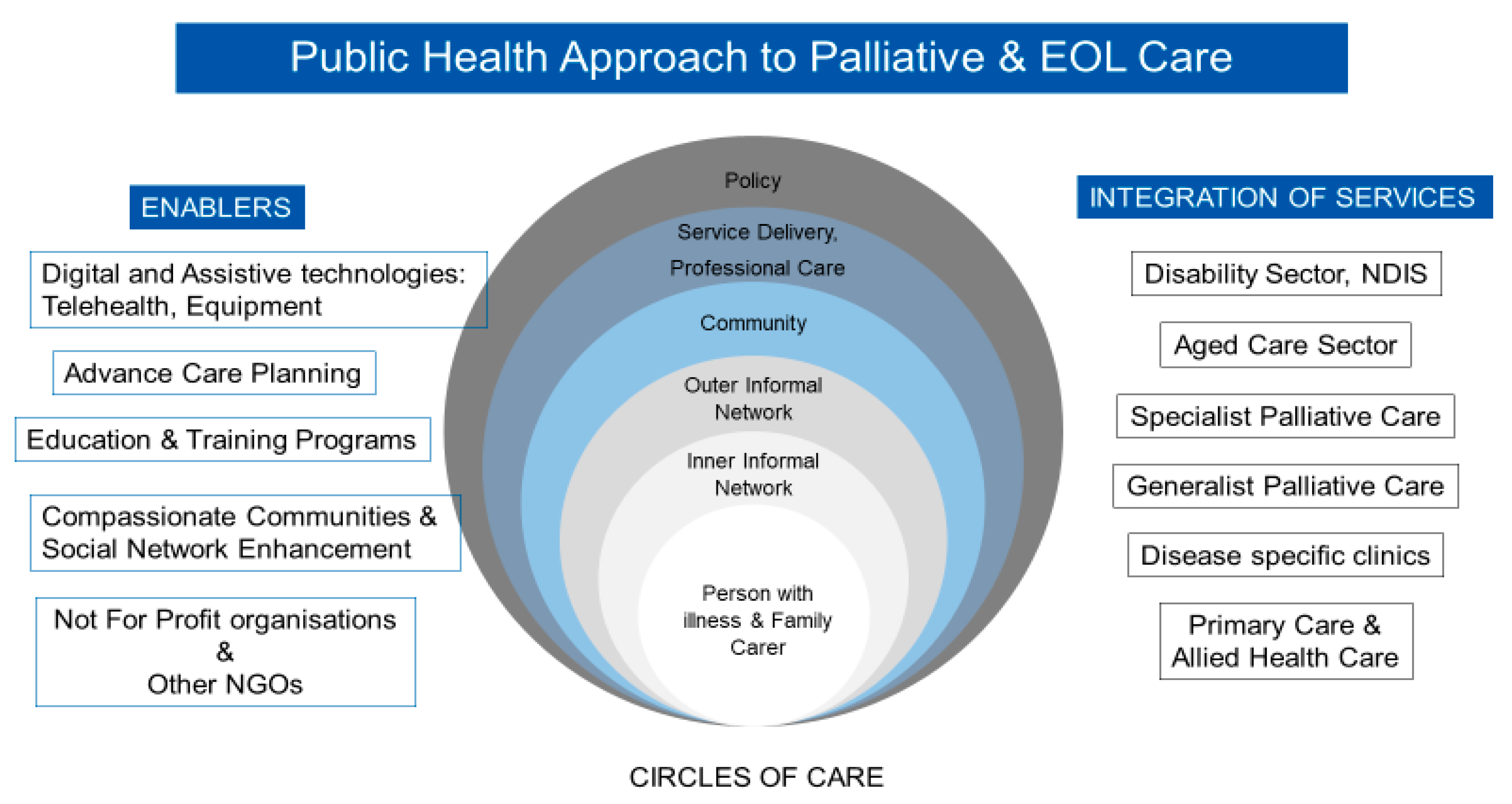

5. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rumbold, B.; Aoun, S.M. Palliative and End-of-Life Care Service Models: To What Extent Are Consumer Perspectives Considered? Healthcare 2021, 9, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sercu, M.; Beyens, I.; Cosyns, M.; Mertens, F.; Deveugele, M.; Pype, P. Rethinking End-of-Life Care and Palliative Care: Learning From the Illness Trajectories and Lived Experiences of Terminally Ill Patients and Their Family Carers. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 2220–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson-Fisher, R.; Fakes, K.; Waller, A.; MacKenzie, L.; Bryant, J.; Herrmann, A. Assessing patients’ experiences of cancer care across the treatment pathway: A mapping review of recent psychosocial cancer care publications. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1997–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerofke-Owen, T.; Garnier-Villarreal, M.; Fial, A.; Tobiano, G. Systematic review of psychometric properties of instruments measuring patient preferences for engagement in health care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1988–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, G.; Gott, M.; Frey, R. ‘It’s my pleasure?’: The views of palliative care patients about being asked to participate in research. Prog. Palliat. Care 2011, 19, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, S.; Slatyer, S.; Deas, K.; Nekolaichuk, C. Family Caregiver Participation in Palliative Care Research: Challenging the Myth. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterell, P.; Harlow, G.; Morris, C.; Beresford, P.; Hanley, B.; Sargeant, A.; Sitzia, J.; Staley, K. Service user involvement in cancer care: The impact on service users. Health Expect. 2010, 14, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hunt, K.; Shlomo, N.; Richardson, A.; Addington-Hall, J. VOICES Redesign and Testing to Inform a National End of Life Care Survey; University of Southampton: Southampton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aoun, S.; Bird, S.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Currow, D. Reliability testing of the FAMCARE-2 scale: Measuring family carer satisfaction with palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, S.M.; Hogden, A.; Kho, L.K. “Until there is a cure, there is care”: A person-centered approach to supporting the wellbeing of people with Motor Neurone Disease and their family carers. Eur. J. Pers. Centered healthc. 2018, 6, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, T.M.; Johnson, C.E.; Lester, L.; Currow, D.; Yates, P.; Allingham, S.F.; Bird, S.; Eagar, K. Perceptions of the care received from Australian palliative care services: A caregiver perspective. Palliat. Support. Care 2018, 16, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, S.M.; Rumbold, B.; Howting, D.; Bolleter, A.; Breen, L. Bereavement support for family caregivers: The gap between guidelines and practice in palliative care. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Western Australia. WA End-of-Life and Palliative Care Strategy 2018–2028; Government of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2018.

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Chung, B.P.M.; Tan, J.-Y. Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, S.M.; Keegan, O.; Roberts, A.; Breen, L.J. The impact of bereavement support on wellbeing: A comparative study between Australia and Ireland. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2020, 14, 2632352420935132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, S.; Prizeman, G.; Coimín, D.Ó; Korn, B.; Hynes, G. Voices that matter: End-of-life care in two acute hospitals from the perspective of bereaved relatives. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, S.M.; Cafarella, P.A.; Hogden, A.; Thomas, G.; Jiang, L.; Edis, R. Why and how the work of Motor Neurone Disease Associations matters before and during bereavement: A consumer perspective. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2021, 15, 26323524211009537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, S.; Toye, C.; Deas, K.; Howting, D.; Ewing, G.; Grande, G.; Stajduhar, K. Enabling a family caregiver-led assessment of support needs in home-based palliative care: Potential translation into practice. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, S.M.; Ewing, G.; Grande, G.; Toye, C.; Bear, N. The Impact of Supporting Family Caregivers before Bereavement on Outcomes After Bereavement: Adequacy of End-of-Life Support and Achievement of Preferred Place of Death. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luymes, N.; Williams, N.; Garrison, L.; Goodridge, D.; Silveira, M.; Guthrie, D.M. “The system is well intentioned, but complicated and fallible” interviews with caregivers and decision makers about palliative care in Canada. BMC Palliat. Care 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, J. Compassionate communities and end-of-life care. Clin. Med. 2018, 18, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbold, B.; Aoun, S. An assets-based approach to bereavement care. Bereave. Care 2015, 34, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, J.; Johnson, M.J. End-of-life care for non-cancer patients. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandeali, S.; Ordons, A.R.D.; Sinnarajah, A. Comparing the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients with non-cancer and cancer diagnoses in a tertiary palliative care setting. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, R.; On behalf of the EOL-CC study authors; Srasuebkul, P.; Langton, J.M.; Haas, M.; Viney, R.; Pearson, S.-A. Health care use and costs at the end of life: A comparison of elderly Australian decedents with and without a cancer history. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, S.M. The palliative approach to caring for motor neurone disease: From diagnosis to bereavement. Eur. J. Pers. Centered Heal. 2018, 6, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, B.; Vogrin, S.; Philip, J.; Hennessy-Anderson, N.; Collins, A.; Burchell, J.; Le, B.; Brand, C.; Hudson, P.; Sundararajan, V. Triaging the Terminally Ill—Development of the Responding to Urgency of Need in Palliative Care (RUN-PC) Triage Tool. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2020, 59, 95–104.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirshberg, E.L.; Butler, J.; Francis, M.; Davis, F.A.; Lee, D.; Tavake-Pasi, F.; Napia, E.; Villalta, J.; Mukundente, V.; Coulter, H.; et al. Persistence of patient and family experiences of critical illness. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Beek, K.; Siouta, N.; Preston, N.; Hasselaar, J.; Hughes, S.; Payne, S.; Radbruch, L.; Centeno, C.; Csikos, A.; Garralda, E.; et al. To what degree is palliative care integrated in guidelines and pathways for adult cancer patients in Europe: A systematic literature review. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, S.M.; Abel, J.; Rumbold, B.; Cross, K.; Moore, J.; Skeers, P.; Deliens, L. The Compassionate Communities Connectors model for end-of-life care: A community and health service partnership in Western Australia. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2020, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, J.; Walter, T.; Carey, L.; Rosenberg, J.; Noonan, K.; Horsfall, D.; Leonard, R.; Rumbold, B.; Morris, D. Circles of care: Should community development redefine the practice of palliative care? BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, D.; Inauen, R.; Binswanger, J.; Strasser, F. Barriers to research in palliative care: A systematic literature review. Prog. Palliat. Care 2015, 23, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, N.G.; Coxon, H.; Nabarro, S.; Hardy, B.; Cox, K. Unmet care needs in people living with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3609–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Healthcare Associates. Australian Department of Health, Exploratory Analysis of Barriers to Palliative Care Summary Policy Paper; Australian Healthcare Associates: Melbourne, Australian, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Number of Respondents | Used Palliative Care (Users) | Did Not Use Palliative Care (Non-Users) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bereaved Carer | 204 | 45 | 249 (71%) |

| Current Carer | 27 | 45 | 72 (20%) |

| Patient | 8 | 24 | 32 (9%) |

| TOTAL | 239 (68%) | 114 (32%) | 353 (100%) |

| Users | Non-Users | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bereaved | Current | Patient | Bereaved | Current | Patient | |||||||

| Carer | Carer | Carer | Carer | |||||||||

| (n = 204) | (n = 28) | (n = 8) | (n = 45) | (n = 45) | (n = 24) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 21 | 10.3 | 6 | 21.4 | 2 | 25 | 4 | 8.9 | 6 | 13.3 | 9 | 37.5 |

| Female | 181 | 88.7 | 22 | 78.6 | 6 | 75 | 41 | 91.1 | 39 | 86.7 | 15 | 62.5 |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| Age, year | ||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 54.6 (13.2) | 46.5 (12.3) | 66.7(9.3) | 57.4 (12.2) | 56.8 (11.3) | 65.7(7.5) | ||||||

| Median (Range) | 55.0 (26–89) | 46 (20–69) | 69 (47–75) | 57 (30–83) | 58 (33–73) | 66 (53–81) | ||||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||||||

| Married/de facto | 91 | 44.6 | 19 | 67.9 | 5 | 62.5 | 26 | 57.8 | 36 | 80 | 13 | 54.2 |

| Widowed | 70 | 34.3 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 10 | 22.2 | 2 | 4.4 | 3 | 12.5 | |

| Other | 38 | 18.6 | 8 | 28.6 | 3 | 37.5 | 8 | 17.8 | 6 | 13.3 | 8 | 33.3 |

| Missing | 5 | 2.5 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 1 | 2.2 | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | - |

| Education Level | ||||||||||||

| University | 102 | 50.5 | 14 | 50 | 2 | 25 | 24 | 53.3 | 26 | 57.8 | 14 | 58.3 |

| Below University | 98 | 49 | 13 | 46.4 | 6 | 75 | 21 | 46.7 | 17 | 37.8 | 10 | 41.7 |

| Missing | 3 | 14.8 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | - |

| Employment Status | ||||||||||||

| Working | 128 | 62.7 | 20 | 71.4 | 0 | - | 29 | 64.4 | 21 | 46.7 | 4 | 16.7 |

| Not Working | 24 | 11.8 | 6 | 21.4 | 2 | 25 | 5 | 11.1 | 11 | 24.4 | 3 | 12.5 |

| Retired | 49 | 24 | 1 | 3.6 | 6 | 75 | 11 | 24.4 | 11 | 24.4 | 17 | 70.8 |

| Missing | 3 | 1.5 | 1 | 3.3 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | - |

| Residential Postcode | ||||||||||||

| Metropolitan | 140 | 68.6 | 18 | 64.3 | 4 | 50 | 34 | 75.6 | 35 | 77.8 | 17 | 70.8 |

| Regional/Rural | 56 | 27.5 | 9 | 32.1 | 3 | 37.5 | 8 | 17.8 | 10 | 22.2 | 6 | 25 |

| Interstate | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 7 | 3.4 | 1 | 3.6 | 1 | 12.5 | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.2 |

| Relationship to Patient | ||||||||||||

| Spouse/Partner | 70 | 34.3 | 5 | 17.9 | - | 11 | 24.4 | 24 | 53.3 | - | ||

| Daughter/Son | 79 | 38.7 | 11 | 39.3 | - | 21 | 46.7 | 16 | 35.6 | - | ||

| Other | 48 | 22.5 | 11 | 39.3 | - | 13 | 28.9 | 5 | 11.1 | - | ||

| Missing | 7 | 3.4 | 1 | 3.6 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | ||

| Disease | ||||||||||||

| Cancer | 118 | 57.8 | 14 | 50.0 | 5 | 62.5 | 17 | 37.8 | 14 | 31.1 | 20 | 83.3 |

| Non–Cancer | 55 | 27 | 12 | 42.9 | 3 | 37.5 | 25 | 55.6 | 30 | 66.6 | 4 | 16.7 |

| Motor Neurone Dis. | 19 | - | 3 | - | 1 | - | 5 | - | 2 | - | - | |

| Dementia | 14 | - | 4 | - | 0 | - | 7 | - | 18 | - | 0 | - |

| Other neurological | 3 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 8 | - | 8 | - | 2 | - |

| Lung/Heart/Kidney | 24 | - | 6 | - | 1 | - | 7 | - | 7 | - | 2 | - |

| Missing/Unknown | 31 | 15.2 | 2 | 7.1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6.7 | 1 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 |

| What Is Working Well | What Is Not Working So Well |

|---|---|

| Priority one: Care is accessible to everyone, everywhere | |

| 78% rated quality of care excellent to good | 60% reported receiving as much support as wanted before death. |

| 84% could access care as soon as they needed. | 50% felt they received enough help after their relative’s death |

| 76% rated relief of pain excellent to good | All indicators lower for non-cancer conditions |

| 70% for relief of symptoms other than pain and practical assistance. | All indicators lower for non-users of palliative care |

| 80% rated quality of EOL care excellent/good and reported they received enough help at time of death (definitely/ to some extent). | |

| Priority Two: Care is person-centred | |

| 83% rated values respected always/most of the time | 58% felt they could discuss worries/fears as much as they wanted |

| 87% rated cultural background respected always/most of the time | 61% rated spiritual support as excellent/good |

| 82% rated spiritual beliefs respected always/most of the time | 64% rated emotional support as excellent/good |

| 69% reported that the services checked if they have EOL wishes documents | All indicators lower for non-cancer conditions |

| 78% felt their wishes were taken into account | All indicators lower for non-users of palliative care |

| 72% of patients felt included in care decisions (excellent/good) | |

| 80% of carers reported being involved in decision making at EOL as much as they wanted | |

| Priority Three: Care is coordinated | |

| 75% found the referral process easy/very easy | 60% reported that services worked well with GP and external services |

| 87% thought staff worked well within each setting (definitely/to some extent) | 10% of ED admissions were planned or coordinated |

| 74% rated out of hours services as excellent/good | All indicators lower for non-cancer conditions |

| Priority Four: Families and carers are supported | |

| 78% reported patients were involved in decisions about their EOL care as much as they wanted | 62% rated emotional support to family carer as excellent/good |

| 60% were provided information on their relative’s condition | |

| 47% of carers reported being able to talk about experience of illness and death to services | |

| 53% of carers were offered information on grief by palliative care services | |

| 42% of carers were contacted by palliative care services 3–6 weeks after death and only 16% six months after death of their relative | |

| All indicators lower for non-cancer conditions | |

| All indicators lower for non-users of palliative care | |

| Priority Five: All staff are prepared to care | |

| 88% thought they were treated with respect/dignity always/most of the time | All indicators lower for non-cancer conditions |

| 89% thought they were treated with compassion/ kindness always/most of the time | |

| 90% rated staff as very competent/competent | |

| 78% said they could obtain information when needed always/most of the time | |

| 86% of carers reported being dealt with in a sensitive manner at death/end of life | |

| Priority Six: The community is aware and able to care | |

| 96% reported they received informal support before death and 92% found this informal support very/quite helpful | Lower rates of helpfulness before and after death for non-users |

| 94% reported they received informal support after death and 87% found this informal support very/quite helpful | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aoun, S.M.; Richmond, R.; Jiang, L.; Rumbold, B. Winners and Losers in Palliative Care Service Delivery: Time for a Public Health Approach to Palliative and End of Life Care. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121615

Aoun SM, Richmond R, Jiang L, Rumbold B. Winners and Losers in Palliative Care Service Delivery: Time for a Public Health Approach to Palliative and End of Life Care. Healthcare. 2021; 9(12):1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121615

Chicago/Turabian StyleAoun, Samar M., Robyn Richmond, Leanne Jiang, and Bruce Rumbold. 2021. "Winners and Losers in Palliative Care Service Delivery: Time for a Public Health Approach to Palliative and End of Life Care" Healthcare 9, no. 12: 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121615

APA StyleAoun, S. M., Richmond, R., Jiang, L., & Rumbold, B. (2021). Winners and Losers in Palliative Care Service Delivery: Time for a Public Health Approach to Palliative and End of Life Care. Healthcare, 9(12), 1615. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9121615